Videogames today can almost all be slotted into one of a collection of relatively stable genres: first-person shooter, real-time-strategy game, point-and-click adventure, action RPG, text adventure, etc. Occasionally a completely original game comes along to effectively carve out a whole new genre, as happened with Diner Dash and the time-management genre respectively in the mid-2000s, but then the variations, refinements, and outright clones follow, and things stabilize once again. One of the things that makes studying the very early days of gaming so interesting, though, is that genres existed in only the haziest sense; everyone was pretty much making it up as they went along, resulting in gameplay juxtapositions that seem odd at first to modern sensibilities. Still, sometimes these experiments can surprise us with how effectively they can work, even make us wonder whether today’s genre-bound game designers haven’t lost a precious sort of freedom. A case in point: Eamon, which used the interface mechanics of the text adventure but largely replaced puzzle-solving with combat, and also inserted an idea taken from Dungeons and Dragons, that of the extended campaign in which the player guides a single evolving character through a whole series of individual adventures.

As an actively going concern for more than twenty years and a system that still sees an occasional trickle of new activity, Eamon is one of the oddest and, in its way, most inspiring stories in gaming history. For such a long-lived system, its early history is surprisingly obscure today, largely because the man who created Eamon, Donald Brown, has for reasons of his own refused to talk about it for nearly thirty years. I respected his oft-repeated wish to just be left alone as I was preparing this post, but I did make contact with another who was there almost from the beginning and who played a substantial role in Eamon‘s evolution: John Nelson, who took over development work on the system after Brown and founded the National Eamon User’s Club. Through Nelson as well as through my usual digging up of every scrap of documented history I could find, I was able to lift the fog of obscurity at least a little.

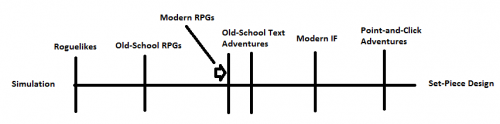

But before we get to that I should tell you what Eamon was and how it worked. Though there have been a handful of attempts to port it to other machines, Eamon had its most popular incarnation by far on the computer on which Brown first created it, the Apple II. The heart of the system was the “Master Diskette,” containing a character-creation utility; a shop for weapons, armor, and spells; a bank for storing gold between adventures; and the first simple adventure, the “Beginner’s Cave.” This master disk was also the springboard for many more adventures, which number more than 250 at this writing. While each of these has many of the characteristics of a free-standing text adventure, there are two huge differences that separate them from the likes of the Scott Adams games: the player imports her own character to play with, with her own attribute scores and equipment; and they mostly replace set-piece puzzles with the tactical dilemmas of simulated combat. On my little continuum of simulation versus set-piece design, in other words, Eamon adventures fall much further to the left than even old-school text adventures, near the spot occupied by old-school RPGs.

To modern sensibilities, then, Eamon adventures are CRPGs disguised as text adventures.

Indeed, the design of Eamon bears the influence of D&D everywhere. The idea of a long-term “campaign” involving the same ever-evolving character comes from there, as does the focus on combat at the expense of more cerebral challenges. In these ways and others it is actually quite similar to Automated Simulations’s Dunjonquest series, of which Temple of Apshai was the first entry. (The Dunjonquest system was also advertised as an umbrella system of rules for which the player bought scenarios to play, just as she bought adventure modules for her tabletop D&D campaign.) Brown is clearly more interested in recreating the experience of an ongoing D&D campaign on the computer than he is in the self-contained storytelling of what has evolved into modern interactive fiction. As such, it represents a fascinating example of a road not taken. (Until recently, perhaps; S. John Ross and Victor Gijsbers have recently been experimenting with the possibilities for tactical combat in IF once again, with results that might surprise you. Notably, both men came to IF from the world of the tabletop RPG.)

Yet Eamon also represents the origin of a road most decidedly taken, one that stretches right up to the present day. It is the first system created specifically for the creation of text adventures. All those who, to paraphrase Robert Wyatt, couldn’t understand why others just play them instead of writing them themselves now had a creative tool for doing just that. It may seem odd to picture Eamon as the forefather of Inform 7 and TADS 3, but that’s exactly what it is. In fact, it is the first game-creation utility of any type to be distributed to the computing public at large.

Brown was a student at Drake University in Des Moines at the time that he created Eamon. While a couple of yearbook photos show him peeking out from the back row of his dorm house’s group pictures, he looks like a fish out of water amongst the other party-hardy types. He receives nary an additional mention in either yearbook, and didn’t even bother to pose for an individual picture. It’s doubtful that he ever graduated. Clearly, Brown’s interests were elsewhere — in two other places, actually.

His father purchased an Apple II very early. Brown was instantly hooked, devoting many hours to exploring the possibilities offered by the little machine. Soon after, a fellow named Richard Skeie started a new store in Des Moines called the Computer Emporium. The CE went beyond merely selling hardware and software, hosting a computer club that met very frequently at the shop itself, and thus becoming a social nexus for early Des Moines microcomputer (particularly Apple II) enthusiasts. Brown was soon spending lots of time there, discussing projects and possibilities, trading software, and socializing amongst peers who shared his geeky obsession with technology.

The other influence that would result in Eamon stemmed from the tabletop wargame and RPG culture that was so peculiarly strong in the American Midwest. Through an older friend named Bill Fesselmeyer, Brown plunged deeply into Dungeons and Dragons. But Fesselmeyer — and, soon enough, Brown — took his medieval fantasies beyond the tabletop, via the Society for Creative Anachronism.

Born out of a spontaneous “protest against the twentieth century” at Berkeley University in 1966, the SCA is a highly structured club — or, some would say, lifestyle — dedicated to reliving the Middle Ages. Still very much alive today, it has included in its ranks such figures as the fantasy authors Diana Paxson (the closest thing it has to a founder) and Marion Zimmer Bradley. From the club’s website:

The Society for Creative Anachronism, or SCA, is an international organization dedicated to researching and re-creating the arts, skills, and traditions of pre-17th-century Europe.

Members of the SCA study and take part in a variety of activities, including combat, archery, equestrian activities, costuming, cooking, metalwork, woodworking, music, dance, calligraphy, fiber arts, and much more. If it was done in the Middle Ages or Renaissance, odds are you’ll find someone in the SCA interested in recreating it.

What makes the SCA different from a Humanities 101 class is the active participation in the learning process. To learn about the clothing of the period, you research it, then sew and wear it yourself. To learn about combat, you put on armor (which you may have built yourself) and learn how to defeat your opponent. To learn brewing, you make (and sample!) your own wines, meads and beers.

That introduction emphasizes the “historical recreation” aspect of the SCA, but one senses that its role-playing element is an equal part of its appeal, and the aspect that most attracted D&D fans like Fesselmeyer and Brown. The SCA’s idea of club organization is to divide North America into “kingdoms,” each ruled by a king and queen. From these heights descend a web of barons and dukes, shires and strongholds. Each member chooses a medieval name and many craft an elaborate fictional persona, coat of arms included. The king and queen of each kingdom are chosen by clash of arms in a grand Crown Tournament. Indeed, chivalrous clashes are much of what the SCA is about; John Nelson told me of stopping by Brown’s house one day to find him and Fesselmeyer “sword fighting in the living room.” There is much about the SCA that resembles an extremely long-term example of the modern genre of live-action role-playing games (LARPs), a genre which itself grew largely out of the tabletop RPG tradition. It’s thus little surprise that Fesselmeyer, Brown, and many other D&D fans found the SCA equally compelling; certainly a large percentage of the latter were also involved in the former, especially in the gaming hotbed that was the Midwest of the 1970s.

If Brown is the father of Eamon, Fesselmeyer (who died in a car crash on his way to an SCA coronation in 1984) is its godfather, for it was he who pushed Brown to combine his interests into a system for role-playing on the computer. Brown likely began distributing Eamon out of the Computer Emporium at some point during the latter half of 1979. From the beginning, he placed Eamon into the public domain; the CE “sold” Eamon and its scenario disks for the cost of the media they were stored on.

In practice, the Eamon concept proved to be both exciting and problematic. I’ll get to that next time, when I look more closely at how Eamon is put together and how a few early adventures actually play.

Felix Pleșoianu

September 18, 2011 at 8:07 pm

Ah, games with no definite genre. They’re my favorites (shameless plug).

I’ve learned of Eamon a few months ago, and it blew my mind that not only such a system existed in 1980, but it’s still being played — and developed for! — more than 30 years later. But I didn’t know about all these connections.

george

September 19, 2011 at 3:12 pm

I wonder if Eamon and its creators have any connection to muds, other than genre?

Matthew Clark

September 19, 2011 at 11:54 pm

You can learn more about Eamon on the website of the Eamon Adventurer’s Guild at http://www.eamonag.org

Matthew Clark

September 22, 2011 at 3:11 am

Oh, and there is additional support to show that Eamon was created before 1980. John Nelson introduced Eamon to Bob Davis in the summer of 1980 and by then, there were already 10 adventures by both Brown and Jim Jacobson. (See pages 5-7 from http://www.eamonag.org/newsletters/acrobat/NEUC8503.pdf.)

Oddly though, in Brown’s Recreational Computing article, published in July/August 1980, he specifically mentions “at the moment, I know of five additional adventure diskettes”. Unless they were double-sided floppies, Brown may not have been fully aware of the games being produced on the system. (See page 36 of http://www.eamonag.org/articles/DonBrown-RecreationalComputing.pdf.)

Scott Everts

March 23, 2012 at 2:02 am

I remember first being introduced to Eamon on a friend’s Apple II+ in early high school. I borrowed his computer over the weekend so I could play the game. I graduated from high school in 1982 and I’m almost positive this was before 1980. This was in Virginia. At one point I owned the whole series and used to order them through the mail from the old Eamon club newsletter. I have an old notebook from that era that I used to have all my documentation. It has the Eamon dragon silkscreened on it.

So many great memories playing these!

firstmethod

May 9, 2013 at 2:17 pm

The first I heard of Eamon, it was in an old Creative Computing article. Then I came across it in Jr. High, must have been 1982, and played Beginner’s Cave on a black Bell + Howell Apple II in the computer lab. I even wrote and published on GEnie an adventure based on Gamma World, years later, for the Atari ST Eamon port, though I can’t find it on the internet anywhere so it must have been lost in time. There is definitely something special about this game, in spite of its limitations. Its too bad Donald Brown won’t break his silence and give some background on its making, this series impacted a lot of peoples lives.

Michael Penner

July 7, 2018 at 4:03 pm

Greetings,

Please forgive the self-promoting; the search engines have not been kind. If you are a fan of Eamon and are unaware this is worth knowing about.

The Eamon CS gaming system is a modern, powerful Eamon with many enhancements, built in the C# language: https://github.com/firstmethod/Eamon-CS

There are currently eight highly polished games built for it, with more to come as time goes by.

Thanks,

M. Penner

Scott Wolchok

July 17, 2018 at 4:56 am

The Donald Brown link in the text is dead.

Jimmy Maher

July 17, 2018 at 9:29 am

Too bad. It’s not been archived either due to robots.txt. Only thing to do is remove it. Thanks!

Jeff Nyman

May 2, 2022 at 7:42 pm

“Still, sometimes these experiments can surprise us with how effectively they can work, even make us wonder whether today’s genre-bound game designers haven’t lost a precious sort of freedom.”

This feels a bit off to me, at least historically. What is Dark Souls, for example? What about The Stanley Parable? What about To The Moon? Feist? Shovel Knight? Mean Streets? Under a Killing Moon? Wing Commander 3? The Swapper? Corpse Party? This War of Mine? Alan Wake? The Walking Dead?

Here I’m clearly just picking games across a span of many years. But I think the key point is that, if anything, we are less “genre-bound” than in the past because the ability to combine genres became much more capable, particularly as ludonarrative concepts took stronger hold, eventually taking us to the ideas of ludonarrative dissonance and harmony and the idea of “role-playing.”

What I do think is clear is something I’ve come to feel after reading these posts: the text adventure was a somewhat (perhaps very) unlikely development to succeed in any way commercially and possibly even unlikely to come to fruition. It got lucky. It managed to fit into a time slot where better options weren’t available yet.

I asked in another comment to another post: what if the PLATO system had been available to Crowther? Would he have created Adventure as he did or rather as it could have been in that context? Obviously we don’t know. But it’s at least arguable that he would have created something like the “dungeon/pedit5/dnd” games that we did see on PLATO. And that likely would have impacted Scott Adams and crew who eventually developed text adventures that — nominally at least — all traced back to Adventure.

“A case in point: Eamon, which used the interface mechanics of the text adventure but largely replaced puzzle-solving with combat, and also inserted an idea taken from Dungeons and Dragons, that of the extended campaign in which the player guides a single evolving character through a whole series of individual adventures.”

Yep. And it’s interesting to consider if Donald Brown and crew would have done something more like the PLATO adventures had that been possible. Certainly they were leaning more into the RPG concept than the text adventure. Text was just the mechanism that they had available to them.

But even this bit of “genre”-conflating, if such it was, pales in comparison to what is attempted closer to our own time frame. So I think historically it’s clear game developers had much less freedom in the past rather than suggesting they had all this freedom that was somehow lost later. The history of gaming shows pretty much the exact opposite. The one thing that’s undeniable is the text adventure “genre” — again, if such it be (as opposed to just a mechanic) — entirely lost out to the RPG. So:

“As such, it represents a fascinating example of a road not taken.”

I think the road was taken in that the text adventure was always doomed to a short life. The road taken was the RPG insinuating itself into more and more game types, Eamon being just a very early example of that. This was seen historically from pretty much the inception of home gaming. Once home/personal computers could do graphics and simulation-style gaming, text adventures pretty much immediately dropped off any radar that mattered.

It’s a fascinating history, for sure! We had wargaming morph into simulation gaming which morphed into experiential gaming that morphed into role-play gaming. Text was just one of the mechanisms along that spectrum with the “text adventure” being (largely) an evolutionary dead-end.

Mike Taylor

May 3, 2022 at 12:01 am

If you think text adventures were an evolutionary dead end, I highly recommend Aaron A. Reed’s recently completed blog “50 Years of Text Games” at https://if50.substack.com/ — It starts where you’d expect, with ELIZA and ADVENT and ZORK, but as it moves through the decades it discusses all sorts of much more experimental games. Where text is still very very strong is as a medium for sketching completely new approaches in a reasonably cheap manner, without need to (for example) craft graphics to show every emotional nuance in the face of every character. Even if people don’t necessarily play text games much now — and Reed’s blog certainly wouldn’t support that contention — it would still be the case that text games are a wonderful medium for experimentation and prototyping.

Jeff Nyman

May 21, 2022 at 1:31 pm

I have read all of that and it is, for sure, interesting … but it really shows that nothing has evolved that much. I agree that there has been some experimentation and prototyping but it really hasn’t led to much beyond text adventures always being what they were. With some development systems for interactive fiction, even the ability to reliably craft the text interface itself is very limited. (I do know about things like Vorple that are trying to change that.)

So when I said an “evolutionary dead end” what I more meant is the form itself isn’t dead but it’s never really evolved all that much beyond what it started as. I do think there was more experimentation around narrative tropes and ways of presentation, which is great to see. But consider how little aspects like ludonarrative dissonance or consonance really get discussed in the context of even modern text adventures. Whatever someone’s stance on those topics is, it’s undeniable that it fostered a lot of discussion around narrative in a game context for just about all other gaming options. Something that text adventures should have been ready to capitalize on and engage with.

And it’s without doubt that text adventures did not really get incorporated into other game types like, say, the RPG concept did. And even in what would ostensibly be a narrative-heavy venue (story-driven text), it’s still the case that the most interesting experiments in gaming over the last couple decades all required engagement with multiple senses: audio, video, and textual. Consider Disco Elysium as a recent example. Or To The Moon. Or What Remains of Edith Finch. Even consider how something like Telltale’s The Walking Dead would be carried out via text adventure — and how much it would likely suffer as a result of being “devolved” to that format.

No game developers (that I’m aware of or can see) are out there thinking “Hmm, I wonder how we bring a bit of the text adventure into our game to create an interesting hybrid?” Whereas that pretty much does happen with just about all other gaming types.

Mike Taylor

May 22, 2022 at 2:47 pm

I don’t quite know what I can say in response to that, Jeff. When early text adventures have led to more sophisticated, experimental and artistic text-based games, you say they haven’t really evolved because they’re still text; but when they have led to graphical games you say text adventures haven’t evolved because they thing they’ve evolved into isn’t a text adventure any more.

Jeff Nyman

July 25, 2022 at 11:10 pm

“When early text adventures have led to more sophisticated, experimental and artistic text-based games…”

I think some text adventures did lead to exactly that: a bit more sophistication and a bit more artistic aspects. Perhaps even a lot more. But it plateaued rather rapidly — and evolutionary considerations are always about the ceiling of a plateau and how rapidly it gets reached.

Read most of the articles on Infocom games on this blog, for example, and you’ll see a trend in the commentary — which I happen to agree with — that while there was some evolution, it never really went too far. Dave Lebling and Marc Blank are even on record as saying the exact same thing. They often felt they struggled on what exactly to do next; where exactly things could evolve beyond a certain point. It’s why they experimented with graphics and varying interfaces. (See this article on this very blog: https://www.filfre.net/2016/07/going-to-california/). Lebling is quoted as saying:

“So, I don’t think Infocom could have continued to go on from strength to strength the way we seemed to have been doing initially; we would have plateaued out. I think we eventually would have had to branch out into other kinds of games ourselves.”

Exactly: plateaued. Marc Blank in the same article:

“To me, the problem was where it could go, whether we had reached some kind of practical limit in terms of writing a story that way.”

Exactly. He’s also quoted as saying:

“worried about this a lot because people would always ask about the next step, the next thing we could do. It really wasn’t clear to me. Okay, you can make the writing better, and you can make puzzles that are more interesting. But as far as pushing toward a real interactive story — in a real story, you don’t just give everyone commands, right? — that was an issue. We worked on some of those issues for quite a while before we realized that we just weren’t getting anywhere.”

Exactly: they weren’t getting anywhere. And if Infocom wasn’t in this space, then likely neither was anyone else. Which history proved to be true.

“but when they have led to graphical games you say text adventures haven’t evolved because they thing they’ve evolved into isn’t a text adventure any more.”

I don’t know that I would say text adventures evolved into the graphical game since graphical game covers a LOT of territory. Even if we say graphical adventure games, it’s like saying the book evolved into the movie because both tell a story. But that’s clearly simplistic. PLATO dungeon games, for example, certainly weren’t something that evolved from text adventures.

That’s why I say it’s quite obvious how the RPG, for example, evolved to be incorporated into all sorts of games (including the text adventure) whereas the text adventure itself has not to the same degree. For sure you see some of that combination of elements in early games like King’s Quest, Space Quest and so on in that there was a text parser and a graphical component. But, of course, there too the parser (relatively) rapidly went away.

Jeff Nyman

July 25, 2022 at 11:18 pm

One extra point, even in terms of the rapid prototyping you mention, I think it’s a great point. Having worked in the game industry for various contract testing purposes, visual prototyping has very much been the preferred style for a very long time and those are what we use as our specifications. When we do grooming sessions, it’s with visual, not textual, prototypes.

As one very specific example, test harnesses use visual orchestrators to model body language and facial animation in response to how dialogue is spoken and if that seems to match the “gravity” of the dialogue. This refers a bit to what you mentioned regarding using text to perhaps prototype “emotional nuance in the face of every character” rather than graphics since text would be cheaper. In modern game design circles, text is seen as absolutely the wrong way to model exactly that kind of thing but, granted, that also is because visual prototyping has evolved so much. By this I mean text is NOT cheaper because it’s seen to lead to more project churn to getting rapid feedback and shortening the cost-of-mistake curve since it lacks the fidelity required.

All that being said, text is used to annotate elements of the test harness to indicate what emotional points should be considered or looked for. But is that the influence of the text adventure? Consider also there are very much the equivalent of textual screenplays written for a lot of games and for that we use screenwriting software; I wouldn’t attribute too much of that to the influence of the text adventure somehow informing the design process, though.

As a final point, I’ll certainly concede that what I’m talking about here is more the professional or semi-commercial gaming market, made up of indie, small, and large game design houses. I entirely understand that in a pure hobbyist context, the above may not be applicable in the same way.