I recently was privileged to have quite an extensive series of email conversations with Mark Pelczarski, a man who played a variety of significant roles in the early software industry. I’m going to relate his story at some length here. Not only is it important in its own right, but it might also help to illustrate just how unique and, for those in the right place with the right skills, empowering those times were. As we move toward the end of 1982 in the chronology of the blog as a whole, we’re also moving into an inevitably more conventionally professional, even mercenary era. So, maybe this tale can also serve as a final goodbye to those halcyon earliest days of the American PC industry. As you’ll see, Mark’s career took in a huge swathe of history, and shows just how much could happen for a driven young man in an amazingly short span of time.

In 1970 a teenage Mark signed up for an introductory computer-programming course at his suburban Chicago high school, one of the few in the country to offer such a thing. The students programmed an IBM 1130 minicomputer housed in cabinets scattered around a special, air-conditioned room, from which mechanical clunks and chatters emitted whenever the computer was in operation. There was a cabinet for the punched-card reader, one for the printer, one for the memory (all of 16 K, mounted on a series of flat plates so that you could see each individual bit), one for the disk drives. In the center of it all was a control console that looked like something out of Star Trek, all flashing lights and switches. The students, however, rarely saw the beast they programmed. They designed and wrote out their FORTRAN programs on paper, then carefully pecked them out on a keypunch machine located in a room adjacent to the computer itself. Finally they delivered their cards to the computer operator, who fed them into the beast itself, and, hours later, delivered a printout showing what (if anything) had happened. That was the nature of the process in 1970 even for many professional programmers.

Still, young Mark was fascinated. He learned a lot during that year, thanks partly to a wonderful teacher, Paul Halac, who managed to cram more into this one-year high-school course than many computer-science majors get in their first year at university. Halac even made an arrangement with a local business to let a few of his exceptional students, Mark among them, visit one evening per week to experience a much more welcoming computing environment: our old friend HP Time-Shared BASIC. A big baseball fan, young Mark also spent some of his free time tinkering with a statistics-driven FORTRAN baseball simulation, which the powers-that-were graciously allowed him to try on the school’s computer. His program played the 1970 World Series again and again; he recalls today that “Baltimore won more frequently than Cincinnati,” just like in the real thing. The direction his life would take was pretty well set by this computer access, so rare for 1970.

University followed — specifically, the University of Illinois, where Mark managed to simultaneously earn a bachelor’s in mathematics and a master’s in education (with an emphasis on computer-aided instruction) in just four years. Here he was once again fortunate in his choice of educational institutions. The University of Illinois, you may remember, was the home base of PLATO, the pioneering and profoundly influential educational-computing network whose personalities, games, and culture would indelibly stamp the early PC era. Mark was hired by the computer-science department as a research assistant, which came with a wonderful perk: a key that gave him total access, day or night, to the building that housed the PLATO terminals. Next to that another bonus that would thrill most students, having his own office right there at the university, paled. He spent many hours hunched over a PLATO terminal, developing a new appreciation for computers as tools for entertainment, creativity, and socializing. In his role as research assistant, he also wrote papers on computer-aided instruction and programmed courseware in BASIC.

Soon after Mark left university, the trinity of 1977 appeared. Before the decade was over, he would have the chance to know all three intimately.

That year Mark was teaching math at another Illinois high school while also struggling to get a computer club started for his students in the face of decidedly limited resources. Early on, the club had no computer access at all; they could only write out their programs on paper and imagine them running on a real machine. (Incredibly, the class actually did very well in a programming contest hosted by a local college with their completely untested programs.) Eventually the school purchased a terminal and arranged with a local community college where Mark was teaching a night course on BASIC programming for dial-up access to their computer system. It was a long way from PLATO, but it was a start. Early in 1978, the school replaced the dumb terminal with a newer, cheaper option: a single TRS-80, which like the terminal had to be shared by all of the students in the computer club and Mark’s new course on “computer math.”

Soon after, Mark bought his first PC of his own — a Commodore PET. As we’ve had occasion to discuss before, the PET never quite attracted the same following in North America as did the TRS-80 and the Apple II, but a hungry if smaller market for games and other programs did exist. Mark wrote a simple football simulation and sold it to Cursor, a subscription service that distributed programs to PET owners on cassette. Soon after, however, he grew disillusioned with his purchase. The original PET’s BASIC was so riddled with bugs and oddities that you kind of have to wonder whether anyone at Commodore ever actually tried to use it at all before sending thousands of machines out the door. For example, the shift key’s function was inverted: you had to press shift to get lower case. (Since the PET was unique amongst the trinity in offering lower-case input at all, perhaps Commodore felt their customers should just shut up and live with this inconvenience.) Mark got fed up, and returned his PET to the store where he had bought it. His career as a software mogul would have to wait a while.

The next year, 1979, brought marriage and a new job teaching COBOL programming at Northern Illinois University. It also brought the Apple II Plus, which was, with its 48 K of memory and readily available floppy-disk drives, a much more refined and usable machine than any of the original trinity. Mark decided to take the microcomputer plunge again. He purchased the Apple, and, naturally, fell to tinkering again.

One aspect of the Apple II had made it unique right from its debut: its support for true bit-mapped graphics programmable on the pixel level, as opposed to the text and character graphics only of the TRS-80 and PET. Every single machine also shipped with a set of paddle controllers, like the aforementioned “hi-res graphics” mode a legacy of Steve Wozniak’s determination that every Apple II must be able to play a good game of Breakout. One fateful day a student of Mark’s who also owned an Apple II showed him a simplistic drawing program he had written in BASIC, which would let the user draw lines and shapes on the screen in hi-res mode using the paddles. Like that first exposure to computers nine years before, this moment would do much to determine the future direction of Mark’s life. The student, possibly with commercial intentions of his own, refused to tell Mark exactly how his program worked. But this demonstration of what was possible was enough. He went home and started hacking, learning as he went about this still relatively little used and little understood aspect of the machine.

Already that fall he had a program he thought he might be able to sell. Giving it the catchy name of “Drawing Program,” he put it on a disk along with a Space Invaders clone and a slot-machine simulation he had written, photocopied some instructions, and stuck it all in the Ziploc bag that was the standard packaging for software in this era. He started visiting local computer stores to demonstrate this new product of “MP Software,” and was happily surprised to discover that they were willing to trade him printers or RAM chips or sometimes even real money for his creation. It began to dawn on Mark that microcomputers could be more than a hobby. But if so, what next? Enter SoftSide.

Like so much else in this article, we’ve encountered SoftSide before in this blog. Founded by Roger Robitaille in 1978 and somewhat forgotten today, it is nevertheless of immense historical importance: as, in its original TRS-80-specific format, the first magazine to focus on a single consumer platform; as the original home of Lance Micklus’s landmark Dog Star Adventure, the urtext of a thousand bedroom-coded BASIC text adventures; as a great booster of the potential of adventure games in general; and as an advertising and/or editorial outlet for the thoughts and work of important early software figures like Scott Adams, the aforementioned Lance Micklus, Ken and Roberta Williams, Doug Carlston, and, soon enough, Mark Pelczarski. That said, the magazine’s importance almost pales next to that of its adjunct, the TRS-80 Software Exchange, which was a vital step on the path toward a real software industry. With its non-exclusive distribution agreements and other author-friendly terms, it enabled those listed above and many more to sell their software nationwide for the first time. In my recent discussions with Mark Pelczarski, he confirmed something I had long suspected, that the magazine was essentially viewed by Robitaille as a promotional tool for his real business of selling software. Indeed, he developed a neat sort of synergy between the two organs. Most readers bought SoftSide for its many BASIC listings for games and other programs — listings that looked appealing but were tedious to enter and prone to typos on the part of both the magazine’s staff and the poor soul trying to copy all of that spaghetti code into her computer. Therefore each SoftSide always included an offer to just buy the things on tape or disk and be done with it. Later SoftSide started offering a service to automatically receive all of each issue’s programs on cassette every month.

The TRS-80 had been the really hot microcomputer when SoftSide was born in late 1978, but by a year later the Apple II also was taking off in a big way in the wake of the II Plus model, about to eclipse the TRS-80 in the vibrancy of its user community and software support if not (immediately) sales. That market looked like a good place for SoftSide to be. And sure enough, one day when flipping through an issue at a newsstand, Mark came across an advertisement for an editor for a new Apple II edition of the magazine. At 25 years old, with exactly zero experience in publishing of any sort, he applied — and was hired as editor of the new magazine, to be called AppleSeed. Those were unusual times, in which just about everyone in the PC industry was an amateur faking it and/or learning as they went. The January 1980 edition was the only one to appear as AppleSeed; they were threatened by an already litigious Apple, and had to change their name to simply SoftSide Apple Edition for the February issue. Mark worked on the magazine from Illinois for the first months. After the spring 1980 semester was done, however, he honored an agreement he had made with Robitaille before taking the job. He quit his comfortable teaching job at Northern Illinois and trekked eastward with his wife Cheryl to Milford, New Hampshire, home of SoftSide‘s offices.

SoftSide in both its TRS-80 and Apple II incarnations was a digest-sized black-and-white publication printed on cheap paper, very similar to the pre-2005 TV Guide. Feeling that a different format was needed for the magazine to get noticed at newsstands and continue to grow, Mark and some of the other staff convinced Robitaille to remake it as a glossy, full-sized magazine. Robitaille decided at the same time to go with a single edition that catered to not just the Apple II and TRS-80 but also newer machines like the Atari 400 and 800. Robitaille asked Mark to oversee the Apple II-oriented sections of the new magazine and to write each issue’s editorial and plenty of additional content, along with many of the type-in program listings which were still the magazine’s main raison d’être.

But there was also still that drawing program, which Mark had continued to tweak and expand over the months. He believes that it was either Robitaille or, most likely, another SoftSide stalwart named George Blank who finally came up with a proper name for it: The Magic Paintbrush. Mark began selling it through what was now called simply The Software Exchange in the wake of Robitaille’s decision to begin dealing in software for most PCs. He labeled it a product of “MP Software,” which could conveniently stand for either “Mark Pelczarski” or “Magic Paintbrush.” The Magic Paintbrush became one of many programs to be accepted by the SoftSide operation during Mark’s tenure whose significance would become clear only in retrospect — programs like the Williams’ Mystery House and Doug Carlston’s Galactic trilogy, not to mention the one that in a very real way made the microcomputer industry, VisiCalc.

Still, times were changing, and the writing was on the wall for the Software Exchange’s brand of non-exclusive software publication. Already many, not least Personal Software of VisiCalc fame, were using the operation not so much as a publisher but as a mail-order storefront, packaging their own software under their own logo and simply advertising it through the Software Exchange. Just a month after the new incarnation of SoftSide appeared, the first issue of the legendary Apple II-specific magazine Softalk arrived. Still fondly remembered today, Softalk became something of a model for the new breed of slick, ordinary-consumer-friendly, often platform-specific computer magazines that would flourish throughout the 1980s. Softalk featured a wide variety of voices within its pages on a wide variety of topics, from program listings to technical explanations to the “soft,” human-interest stories on the personalities behind the Apple II industry that the magazine always did exceptionally well and is most beloved for today. Also present were lots of outside advertisements from, among others, the many publishers that were springing up to slowly obsolete the likes of the Software Exchange. Robitaille, meanwhile, continued to include articles from just a handful of regular contributors and continued to reject outside advertising. With its usefulness diluted by its need to address so many platforms and its editorial integrity compromised somewhat, at least in the eyes of many readers, by its function as a front for a software sales operation, SoftSide‘s popularity waned in comparison with that of Softalk amongst Apple II owners. This situation caused some angst for Mark, himself after all an Apple II loyalist. At the end of 1980, with he and his wife homesick on top of everything else, he resigned as editor, although he would continue to write programs and a column for SoftSide for some months more. The couple moved back to Chicago.

It was, once again, time to ponder next moves. Having been so involved with the Software Exchange, Mark fell to considering whether there might be a better model for selling software via mail order. Inspiration came from an unlikely source.

During the 1970s Mark had spent several summers staying with friends in Berkeley, California, where he had learned to be quite the outdoorsman. He had hiked Tijuana and British Columbia, Yosemite and Kings Canyon, Half Dome and the Grand Canyon. He’d bought most of his equipment for these adventures from REI (Recreational Equipment, Inc.), and been very impressed with the experience. A co-operative with members rather than customers, REI emphasized service and information, to the extent that actually selling merchandise often seemed rather a secondary goal of the whole operation. Mark told me of purchasing a tent whose fiberglass poles started to split after several years of use. When he asked REI whether he could buy replacements, they gave him a set of new, redesigned poles for nothing, which he still uses to this day. Mark and Cheryl decided to found a new venture called Micro Co-op on the REI model. They would stock only software that they considered truly worthwhile, and would sell it through a catalog that emphasized information and customer empowerment rather than the hard sell, with unbiased comparative reviews by Mark himself.

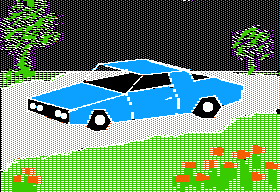

Meanwhile Mark continued to tinker with his drawing program. On-Line’s recent The Wizard and the Princess had revolutionized Apple II graphics in two ways: through its use of vector drawing routines to pack a heretofore inconceivable number of pictures on a single disk, which we’ll talk about again shortly; and through its use of dithering to make the Apple II’s meager six colors look like many more. Mark found that he could make about a hundred colors by mixing the basic six, as long as you stood far enough back from the monitor that the pixels blended. Cheryl got used to the shouts of excitement from his office: “I figured out a way to get four more!” He incorporated these revelations into a new drawing program to sell through Micro Co-op as a product of “Co-op Software”: The Complete Graphics System. The “complete” was perhaps overambitious, but it was at least more complete than anything else at the time. From its first advertisement in May of 1981, it became a hit — such a hit that it forced Mark to consider whether there was any point in continuing Micro Co-op in lieu of becoming a full-time developer and publisher. Within days CGS was bringing in more than the rest of the operation combined; the answer soon seemed obvious. But what to call this new venture that was about to swallow the old? Once again inspiration came from an unlikely source.

During the previous year, a reader of SoftSide had sent in a legitimate query about a program published in an earlier issue with an off-the-wall postscript: what, he asked, do the initials in MP Software stand for? Mark was apparently in a silly mood, because he replied, as printed in the October 1980 edition of the magazine, that they stood for neither “Mark Pelczarski” nor “Magic Paintbrush,” but rather “Magnificent Penguin,” accompanying the reply with a little doodle of the bird in question. Partly it was just inanity for inanity’s sake, partly an homage to the inanity of Monty Python (another coincidental MP). When the time came to release CGS, Mark incorporated a similar doodle into the Co-op Software logo on the box, again more just for the hell of it than due to any conscious reasoning. Shortly after, one David Lubar wrote about CGS in a comparison of graphics software for Creative Computing; the section dedicated to CGS he labeled “Penguin Graphics.” Co-op Software wasn’t the catchiest name for a software publisher, and “Penguin” did have a certain ring to it… and so Penguin Software was born.

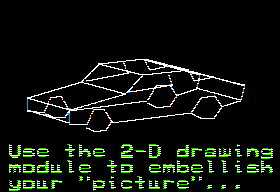

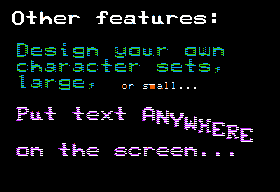

David Lubar’s review did more than give Penguin its name. It also prompted the two men to talk and begin to exchange ideas. David was also a talented programmer who had been dabbling in graphics programming for some months, developing a variety of quite sophisticated transformations — flipping pictures side-to-side or upside-down, or creating color image “negatives” or mirror images. Together the two devised the concept of painting with custom “brushes” of different patterns, implementing many of the concepts that have remained with paint programs to this day. Given the pioneering work done in computer graphics at places like Xerox PARC, it’s arguable how much of this was truly new to the world, but it was devised by Mark and David, who lacked any experience in such environments, from essentially whole cloth. (That such pioneering work was left unpatented and thus free to be further developed is something to be thankful for in these days when Apple and Samsung war over who first thought of rounded corners.) The first fruit of their joint labor appeared in October of 1981 as Special Effects, an add-on to CGS which admittedly did rather give the lie to its name. (The two packages were eventually sold together as The Complete Graphics System II). Key to the appeal of these programs was the way that the documentation described how to use the images you created in your own program, whether it be an arcade game, a graphic adventure in the On-Line mold, or something else. Penguin could soon begin calling themselves, without hyperbole, “the leader in Apple II graphics.” But even better graphics software was still to come.

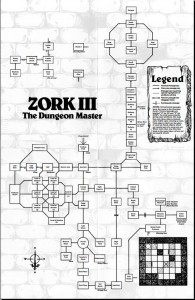

For some time now people had been inquiring just how On-Line managed to get so many pictures on a single disk in their Hi-Res Adventure line. (For example, in one of those discoveries that can make trolling through the old magazines so much fun, you’ll find a letter from a young Brian Fargo in the January 1982 Softline asking just that.) As I explained in a much earlier post, Ken Williams’s genius here was to store each picture on disk not as a grid of static pixels but as a series of instructions that the computer could use to “draw” the picture all over again. For their next release, The Graphics Magician, Mark and David implemented this technique into their own storage routines, with similarly huge space savings. At last developers had the ideal tool for crafting adventure-game graphics, as well as pictures for many other purposes. They could also now use The Graphics Magician to make animations, thanks to some input from a third programmer, Chris Jochumson, whom Mark bumped into one day in Doug Carlston’s living room.

The Graphics Magician was also unusually user friendly (a term much in vogue at the time) in ways that had nothing to do with the actual program on the disk.

First, Mark took the near-revolutionary step of releasing it with no copy protection whatsoever, a move that such luminaries as Al Tommervik, publisher of Softalk, pronounced tantamount to suicide. Developers could secure their investment by making all the backup copies they wanted. That may seem like an obvious “feature” for a serious application today, but in 1982 it was very unusual. Even VisiCalc, the most serious, business-oriented application there was, was designed to be uncopyable. When your disk failed, you simply had to put your business on hold while you waited for a replacement under VisiCorp’s warranty which was hardly a warranty at all; a new disk could cost you up to $40. Those for whom VisiCalc was a truly critical application soon took to simply buying two copies from the start. Penguin’s rejection of copy protection for The Graphics Magician thus made a real rhetorical statement about the rights of users in an industry heretofore obsessed only with those of creators to protect themselves from piracy. In its wake — and that of Penguin’s spectacular failure to go out of business as a result — other publishers slowly began to follow its example. Soon applications software was expected by everyone to be free from copy protection as a matter of course, although games, always the pirates’ favorite and a market with much thinner profit margins, would not follow suit.

Second, this quite inexpensive package, with a list price of just $60 and a street price of considerably less, could nevertheless be freely used to create commercial games with no further licensing. There was just one requirement, a stroke of near genius on Mark’s part: the work in question had to prominently credit the software that had been used to create it. Soon credits screens like this one (from the SAGA version of Scott Adams’s Pirate Adventure) were everywhere, giving Penguin an unbelievable amount of free advertising — and through their competitors’ products at that.

In the wake of The Graphics Magician, adventures with graphics got a whole lot easier to make. Soon they were everywhere, all but swamping pure text adventures on the Apple II. Well before the end of 1982 Penguin stopped calling themselves “the leader in Apple II graphics.” Now they were just “the graphics people,” virtually unchallenged within their niche.

Mark was also firmly ensconced in what Doug Carlston called the “Brotherhood” as the clock slowly ran down on this era of friendly sharing and not terribly competitive competition. He socialized with the Carlstons, the Williams, the Tommerviks; chatted with Mitch Kapor about the project that would become Lotus 1-2-3; discussed adventure games with Scott Adams and Marc Blank. He had long ago been shocked to realize that he was making more money each month with Penguin than he had in a year of teaching. Penguin was a big success, almost accidentally so, all on the strength of essentially that one program he had first begun to develop back in 1979. Masters of their niche, they could think about diversification. Indeed, they were suddenly attracting outsiders with programs — mostly games, usually created using their own graphics software — which they were eager to have Penguin consider. We’ll look at one of those next time.