From the time that Richard and Robert Garriott first founded Origin Systems in order to publish Ultima III, the completion of one Ultima game was followed almost immediately by the beginning of work on the next. Ultima VI in early 1990 was no exception; there was time only for a wrap party and a couple of weeks of decompression before work started on Ultima VII. The latter project continued even as separate teams made the two rather delightful Worlds of Ultima spinoffs using the old Ultima VI engine, and even as another Origin game called Wing Commander sold far more copies than any previous Ultima, spawning an extremely lucrative new franchise that for the first time ever made Origin into something other than The House That Ultima Built.

But whatever the source, money was always welcome. The new rival for the affections of Origin’s fans and investors gave Richard Garriott more of it to play with than ever before, and his ambitions for his latest Ultima were elevated to match. One of the series’s core ethos had always been that of continual technological improvement. Garriott had long considered it a point of pride to never use the same engine twice (a position he had budged from only reluctantly when he allowed the Worlds of Ultima spinoffs to be made). Thus it came as no surprise that he wanted to push things forward yet again with Ultima VII. Even in light of the series’s tradition, however, this was soon shaping up to be an unusually ambitious installment — indeed, by far the most ambitious technological leap that the series had made to date.

As I noted in my article on that game, the Ultima VI engine was, at least when seen retrospectively, a not entirely comfortable halfway point between the old “alphabet soup” keyboard-based interface of the first five games and a new approach which fully embraced the mouse and other modern computing affordances. Traces of the old were still to be found scattered everywhere amidst the new, and using the interface effectively meant constantly switching between keyboard-centric and mouse-centric paradigms for different tasks. Ultima VII would end such equivocation, shedding all traces of the interfaces of yore.

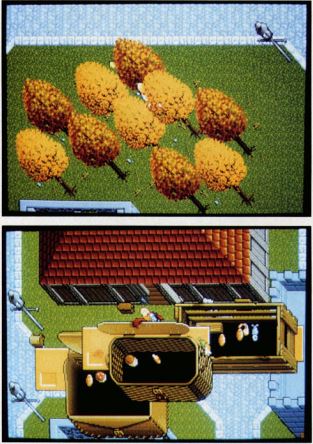

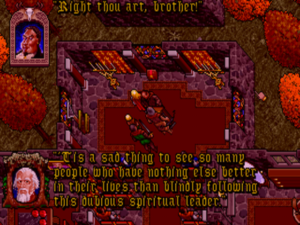

These screenshots from a Computer Gaming World preview of the game provide an interesting snapshot of Ultima VII in a formative state. The graphics are less refined than the final version, but the pop-up interface and the graphical containment model — more on that fraught subject later — are in place.

For the first time since Richard Garriott had discovered the magic of tile graphics in his dorm room at the University of Texas, the world of this latest Ultima was not to be built using that technique; Origin opted instead for a free-scrolling world shown from an overhead perspective, canted just slightly to convey the impression of depth. Gone along with the discrete tiles were the discrete turns of the previous Ultima games, replaced by true real-time gameplay. The world model included height — 16 possible levels of it! — as well as the other dimensions; characters could climb stairs to other floors in a building or walk up a hillside outdoors while remaining in the same contiguous space. In a move that must strike anyone familiar with the games of today as almost eerily prescient, Origin excised any trace of static onscreen interface elements. Instead the entire screen was given over to a glorious view of Britannia, with the interface popping up over this backdrop as needed. The whole production was designed with the mouse in mind first and foremost. Do you want your character to pick up a sword? Click on him to bring up his paper-doll inventory display, then drag the sword with the mouse right out of the world and into his hand. All of the things that the Ultima VI engine seemed like it ought to be able to do, but which proved far more awkward than anticipated, the Ultima VII engine did elegantly and effortlessly.

Looking for a way to reduce onscreen clutter and to show as much of the world of Britannia as possible at one time, Origin realized they could pop up interface elements only when needed. This innovation, seldom seen before, has become ubiquitous in the games — and, indeed, in the software in general — of today.

Origin had now fully embraced a Hollywood-style approach to game production, marked by specialists working within strictly defined roles, and the team which built Ultima VII reflected this. Even the artists were specialized. Glen Johnson, a former comic-book illustrator, was responsible for the characters and monsters as they appeared in the world. Micael Priest was the resident portrait artist, responsible for the closeups of faces that appeared whenever the player talked to someone. The most specialized artistic role of all belonged to Bob Cook, a landscape artist hired to keep the multi-level environment coherent and proportional.

Of course, there were plenty of programmers as well, and they had their work cut out for them. Bringing Garriott’s latest Ultima to life would require pushing the latest hardware right to the edge and, in some situations, beyond it. Perhaps the best example of the programmers’ determination to find a way at all costs is their Voodoo memory manager. Frustrated with MS-DOS’s 640 K memory barrier and unhappy with all of the solutions for getting around it, the programming team rolled up their sleeves and coded a solution of their own from scratch. It would force virtually everyone who played the game at its release to boot their machines from a custom floppy, and would give later users even more headaches; in fact, it would render the game unplayable on many post-early-1990s machines, until the advent of software emulation layers like DOSBox. Yet it was the only way the programming team could make the game work at all in 1992.

As usual for an Ultima, the story and structure of play evolved only slowly, after the strengths and limitations of the technology that would need to enable them were becoming clear. Richard Garriott began with one overriding determination: he wanted a real bad guy this time, not just someone who was misguided or misunderstood: “We wanted a bad guy who was really evil, truly, truly evil.” He envisioned an antagonist for the Avatar cut from the classic cloth of novelistic and cinematic villains, one who could stick around for at least the next few games. Thus was born the disembodied spirit of evil known as the Guardian, who would indeed proceed to dog the Avatar’s footsteps all the way through Ultima IX. One might be tempted to view this seeming return to a black-versus-white conception of morality as a step back for the series thematically. But, as Garriott was apparently aware, the moral plot twists of the previous two games risked becoming a cliché in themselves if perpetuated indefinitely.

Then too, while Ultima VII would present a story carrying less obvious thematic baggage than the last games, that story would be executed far more capably than any of those others. For, as the most welcome byproduct of the new focus on specialization, Origin finally hired a real writing team.

Raymond Benson and Richard Garriott take the stage together for an Austin theatrical fundraiser with a Valentines Day theme. Benson played his “love theme” from Ultima VII while Garriott recited “The Song of Solomon” — with tongue planted firmly in cheek, of course.

The new head writer, destined to make a profound impact on the game, was an intriguingly multi-talented fellow named Raymond Benson. Born in 1955, he was a native of Origin’s hometown of Austin, Texas, but had spent the last decade or so in New York City, writing, directing, and composing music for stage productions. As a sort of sideline, he’d also dabbled in games, writing an adventure for the James Bond 007 tabletop RPG and writing three text-adventure adaptations of popular novels during the brief mid-1980s heyday of bookware: The Mist, A View to a Kill, and Goldfinger. Now, he and his wife had recently started a family, and were tired of their cramped Manhattan flat and the cutthroat New York theater scene. When they saw an advertisement from Origin in an Austin newspaper, seeking “artists, musicians, and programmers,” Benson decided to apply. He was hired to be none of those things — although he would contribute some of his original music to Ultima VII — but rather to be a writer.

When he crossed paths with the rest of Origin Systems, Benson was both coming from and going to very different places than the majority of the staff there, and his year-long sojourn with them proved just a little uncomfortable. Benson:

It was like working in the boys’ dormitory. I was older than most of the employees, who were 95 percent male. In fact, I believe less than ten out of fifty or sixty employees were over thirty, and I was one of them. So, I kind of felt like the old fart a lot of times. Most of the employees were young single guys, and it didn’t matter to them if they stayed at the office all night, had barbecues at midnight, and slept in a sleeping bag until noon. Because I had a family, I needed to keep fairly regular 8-to-5 hours, which is pretty impossible at a games company.

A snapshot of the cultural gulf between Benson and the average Origin employee is provided by an article in the company’s in-house newsletter entitled “What Influences Us?” Amidst lists of “favorite fantasy/science fiction films” and “favorite action/adventure films,” Benson chooses his “ten favorite novels,” unspooling an eclectic list that ranges from Dracula to The Catcher in the Rye, Lucky Jim to Maia — no J.R.R. Tolkien or Robert Heinlein in sight!

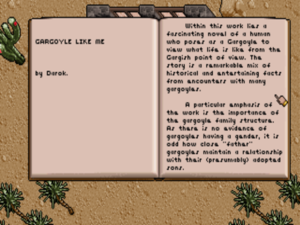

Some of the references in Ultima VII feel like they just had to have come directly from the slightly older, more culturally sophisticated diversified mind of Raymond Benson. Here, for instance, is a riff on Black Like Me, John Howard Griffin’s landmark work of first-person journalism about racial prejudice in the United States.

It’s precisely because of his different background and interests that Benson’s contribution to Ultima VII became so important. Most of the writing in the game was actually dialog, and deft characterization through dialog was something his theatrical background had left him well-prepared to tackle. Working with and gently coaching a team consisting of four other, less experienced writers, he turned Richard Garriott’s vague story outline, about the evil Guardian and his attempt to seize control of Britannia through a seemingly benign religious movement known as the Fellowship, into the best-written Ultima ever. The indelible Ultima tradition of flagrantly misused “thees” and “thous” aside, the writing in Ultima VII never grates, and frequently sparkles. Few games since the heyday of Infocom could equal it. Considering that Ultima VII alone has quite possibly as much text as every Infocom game combined, that’s a major achievement.

The huge contributions made by Raymond Benson and the rest of the writing team — not to mention so many other artists, programmers, and environment designers — do raise the philosophical question of how much Ultima VII can still be considered a Richard Garriott game, full stop. From the time that his brother Robert convinced him that he simply couldn’t create Ultima V all by himself, as he had all of his games up to that point, Richard’s involvement with the nitty-gritty details of their development had become steadily less. By the early 1990s, we can perhaps already begin to see some signs of the checkered post-Origin career in game development that awaited him — the career of a basically good-natured guy with heaps of money, an awful lot of extracurricular interests, and a resultant short attention span. He was happy to throw out Big Ideas to set the direction of development, and he clearly still relished demonstrating Origin’s latest products and playing Lord British, but his days of fussing too much over the details were, it seems, already behind him by the time of Ultima VII. Given a choice between sitting down to make a computer game or throwing one of his signature birthday bashes or Halloween spook houses — or, for that matter, merely playing the wealthy young gentleman-about-town in Austin high society more generally — one suspects that Garriott would opt for one of the latter every time.

Which isn’t to say that his softer skill set wasn’t welcome in a company in transition, in which tensions between the creative staff and management were starting to become noticeable. For the people on the front line actually making Ultima VII, working ridiculous hours under intense pressure for shockingly little pay, Garriott’s talents meant much indeed. He would swoop in from time to time to have lunch catered in from one of Austin’s most expensive restaurants. Or he would tell everyone to take the afternoon off because they were all going out to the park to eat barbecue and toss Frisbees around. And of course they were always all invited to those big parties he loved to throw.

Still, the tensions remained, and shouldn’t be overlooked. Lurking around the edges of management’s attitude toward their employees was the knowledge that Origin was the only significant game developer in Austin, a fast-growing, prosperous city with a lot of eager young talent. Indeed, prior to the rise of id Software up in Dallas, they had no real rival in all of Texas. Brian Martin, a scripter on Ultima VII, remembers being told that “people were standing in line for our jobs, and if we didn’t like the way things were, we could just leave.” Artist Glen Johnson had lived in Austin at the time Origin hired him to work in their New Hampshire office, only to move him back to Austin once again when that office was closed; he liked to joke that the company had spent more money on his plane fare during his first year than on his salary.

The yin to Richard Garriott’s yang inside Origin was Dallas Snell, the company’s hard-driving production manager, who was definitely not the touchy-feely type. An Origin employee named Sheri Graner Ray recounts her first encounter with him:

My interviews at Origin Systems culminated with an interview with Dallas Snell. He didn’t turn away from his computer, but sort of waved a hand in the general direction of a chair. I hesitantly took a seat. Dallas continued to type for what seemed to me to be two or three hours. Finally, he stopped, swung around in his desk chair, leaned forward, put one hand on his knee and the other on his hip, narrowed his eyes at me, and said, “You’re here for me to decide if I LIKE you.” I was TERRIFIED. Well, I guess he did, cuz I got the job, but I spent the next year ducking and avoiding him, as I figured if he ever decided he DIDN’T like me, I was in trouble!

Snell’s talk could make Origin’s games sound like something dismayingly close to sausages rolling down a production line. He was most proud of Wing Commander and Savage Empire, he said, because “these projects were done in twelve calendar months or less, as compared to the twenty-to-thirty-month time frame that previous projects were developed in!” Martian Dreams filled six megabytes on disk, yet was done in “seven calendar months!!! Totally unprecedented!!” Wing Commander II filled 15 megabytes, yet “the entire project will have been developed in eight calendar months!!!” He concluded that “no one, absolutely no one, has done what we have, or what we are yet still capable of!!! Not Lucasfilm, not Sierra, not MicroProse, not Electronic Arts, not anyone!” The unspoken question was, at what cost to Origin’s staff?

It would be unfair to label Origin Systems, much less Dallas Snell alone, the inventor of the games industry’s crunch-time culture and its unattractive byproduct and enabler, the reliance on an endless churn of cheap young labor willing to let themselves be exploited for the privilege of making games. Certainly similar situations were beginning to arise at other major studios in the early 1990s. And it’s also true that the employees of Origin and those other studios were hardly the first ones to work long hours for little pay making games. Yet there was, I think, a qualitative difference at play. The games of the 1980s had mostly been made by very small teams with little hierarchy, where everyone could play a big creative role and feel a degree of creative ownership of the end product. By the early 1990s, though, the teams were growing in size; over the course of 1991 alone, Origin’s total technical and creative staff grew from 40 to 120 people. Thus companies like Origin were instituting — necessarily, given the number of people involved — more rigid tiers of roles and specialties. In time, this would lead to the cliché of the young 3D modeller working 100-hour weeks making trees, with no idea of where they would go in the finished game and no way to even find out, much less influence the creative direction of the final product in any more holistic sense. For such cogs in the machine, getting to actually make games (!) would prove rather less magical than expected.

Origin was still a long way from that point, but I fancy that the roots of the oft-dehumanizing culture of modern AAA game production can be seen here. Management’s occasional attempts to address the issue also ring eerily familiar. In the midst of Ultima VII, Dallas Snell announced that “the 24-hour work cycle has outlived its productivity”: “All employees are required to start the day by 10:00 AM and call it a day by midnight. The lounge is being returned to its former glory (as a lounge, that is, without beds).” Needless to say, the initiative didn’t last, conflicting as it did with the pressing financial need to get the game done and on the market.

Simply put, Ultima VII was expensive — undoubtedly the most expensive game Origin had ever made, and one of the most expensive computer games anyone had yet made. Just after its release, Richard Garriott claimed that it had cost $1 million. Of course, the number is comically low by modern standards, even when adjusted for inflation — but this was a time when a major hit might only sell 100,000 units rather than the 10 million or so of today.

Origin had first planned to release Ultima VII in time for the Christmas of 1991, an impossibly optimistic time frame (impossibly optimistic time frames being another trait which the Origin of the early 1990s shares with many game studios of today). When it became clear that no amount of crunch would allow the team to meet that deadline, the pressure to get it out as soon as possible after Christmas only increased. Looking over their accounts at year’s end, Origin realized that 90 percent of their revenue in 1991 had come through the Wing Commander franchise; had Wing Commander II not become as huge a hit as the first installment, they would have been bankrupt. This subsidizing of Ultima with Wing Commander was an uncomfortable place to be, and not just for the impact it might have had on Lord British’s (alter) ego. It meant that, with no major Wing Commander releases due in 1992, an under-performing Ultima VII could take down the whole company. Many at Origin were surprisingly clear-eyed about the dangers which beset them. Mike McShaffry, a programmer and unusually diligent student of the company’s financial situation among the rank and file — unsurprisingly, he would later become an entrepreneur himself — expressed his concern: “The road ahead for us is a bumpy one. Many companies do not survive the ‘boom town’ growth phase that we have just experienced.”

Thus when Ultima VII: The Black Gate — the subtitle was an unusually important one, given that Origin had already authorized a confusingly titled Ultima VII Part Two using the same game engine — shipped on April 16, 1992, the whole company’s future was riding on it.

Classic games, it seems to me, can be plotted on a continuum between two archetypes. At one pole are the games which do everything right — those whose designers, faced with a multitude of small and large choices, have made the right choice every time. Ultima Underworld, the spinoff game which Origin released just two weeks before Ultima VII, is one of these.

The other archetypal classic game is much rarer: the game whose designers have made a lot of really problematic choices, to the point that certain parts of it may be flat-out broken, but which nevertheless charms and delights due to some ineffable spirit that overshadows everything else. Ultima VII is the finest example of this type that I can think of. Its list of trouble spots is longer than that of many genuinely bad games, and yet its special qualities are so special that I can only recommend that you play it.

Inventory management in Ultima VII. It’s really, really hard to find anything, especially in the dark. Of course, I could fire up a torch… but wait! My torches are buried somewhere under all that mess in my pack.

Any list of that which is confusing, infuriating, or just plain boring in Ultima VII must start with the inventory-management system. The drag-and-drop approach to same is brilliant in conception, but profoundly flawed in execution. You need to cart a lot of stuff around in this game — not just weapons and armor and quest items and money and loot, but also dozens of pieces of food to keep your insatiable characters fed on their journeys and dozens or hundreds of magic reagents to let you cast spells. All of this is lumped together in your characters’ packs as an indeterminate splodge of overlapping icons. Unless you formulate a detailed scheme of exactly what should go where and stick to it with the rigidity of a pedant, you’ll sometimes find it impossible to figure out what you actually have and where it is on your characters’ persons. When that happens, you’ll have to resort to finding a clear spot of ground and laying out the contents of each pack on it one by one, looking for that special little whatsit.

Keys belong to their own unique circle of Inventory Hell. Just a few pixels big, they have a particular tendency to get hopelessly lost at the bottom of your pack along with those leftover leeks you picked up for some reason in the bar last night. Further, keys are distinguished only by their style and color — the game does nothing so friendly as tell you what door a given key opens, even after you’ve successfully used it — and there are a lot of them. So, you never feel quite confident when you can’t open a door that you haven’t just overlooked the key somewhere in the swirling chaos vortex that is your inventory. If you really love packing your suitcase before a big trip, you might enjoy Ultima VII‘s inventory management. Otherwise, you’ll find it to be a nightmare.

The combat system is almost as bad. Clearly Origin, to put it as kindly as possible, struggled to adapt combat to the real-time paradigm. While you can assemble a party of up to eight people, you can only directly control the Avatar himself in combat, and that only under a fairly generous definition of “control.” You click a button telling your people to start fighting, whereupon everyone, friend and foe alike, converges upon the same pixel as occasional words — “Aargh!,” “To arms!,” “Vultures will pick thy bones!” — float out of the scrum. The effect is a bit like those old Warner Bros. cartoons where Wile E. Coyote and the Road Runner disappear into a cloud of arms and legs until one of them pops out victorious a few seconds later.

The one way to change this dynamic also happens to be the worst possible thing you can do: equipping your characters with ranged weapons. This will cause them to open fire indiscriminately in the vague direction of the aforementioned pixel of convergence, happily riddling any foes and friends alike who happen to be in the way full of arrows. In light of this, one can only be happy that the Avatar is the only one allowed to use magic; the thought of this lot of nincompoops armed with fireballs and magic missiles is downright terrifying. Theoretically, it’s possible to control combat to some degree by choosing from several abstract strategies for each character, and to directly intervene with the Avatar by clicking specific targets, but in practice none of it makes much difference. By the time some of your characters start deciding to throw down all their weapons and hide in a corner for no apparent reason, you just shrug and accept it; it’s as explicable as anything else here.

You’ll learn to dread your party’s constant mewling for food, not least because it forces you to engage with the dreadful inventory system. (No, they can’t feed themselves. You have to hand-feed each one of them like a little birdie.)

Thankfully, nothing else in the game is quite as bad as these two aspects, but there are other niggling annoyances. The need to manually feed your characters is prominent among them. There’s no challenge to collecting food, given that there are lots of infallible means of collecting money to buy it. The real problem is that those means are all so tedious. (I spent literally hours when I played the game marching back and forth from one end of the town of Britain to the other, buying meat cheap and selling it expensive, all so as to buy yet more meat to feed my hungry lot.) The need for food serves only to extend the length of a game that doesn’t need to be extended, and to do it in the most boring way possible.

But then, this sort of thing had always been par for the course with any Ultima, a series that always tended to leaven its inspired elements with a solid helping of tedium. And then too, Ultima had always been a little wonky when it came to its mechanics; Richard Garriott ceded that ground to Wizardry back in the days of Ultima I, and never really tried to regain it. Still, it’s amazing how poorly Ultima VII, a game frequently praised as one of the best CRPGs ever made, does as a CRPG, at least as most people thought of the genre circa 1992. Because there’s no interest or pleasure in combat, there’s no thrill to leveling up or collecting new weapons and armor. You have little opportunity to shape your characters’ development in any way, and those sops to character management that are present, such as the food system, merely annoy. Dungeons — many or most of them optional — are scattered around, but they’re fairly small while still managing to be confusing; the free-scrolling movement makes them almost impossible to map accurately on paper, yet the game lacks an auto-map. If you see a CRPG as a game in the most traditional sense of the word — as an intricate system of rules to learn and to manipulate to your advantage — you’ll hate, hate, hate Ultima VII for its careless mechanics. One might say that it’s at its worst when it actively tries to be a CRPG, at its best when it’s content to be a sort of Britannian walking simulator.

And yet I don’t dislike the game as much as all of the above might imply. In fact, Ultima VII is my third favorite game to bear the Ultima name, behind only Martian Dreams and the first Ultima Underworld. The reason comes down to how compelling the aforementioned walking simulator actually manages to be.

I’ve never cared much one way or the other about Britannia as a setting, but darned if Ultima VII doesn’t shed a whole new light on the place. At its best, playing this game is… pleasant, a word not used much in regard to ludic aesthetics, but one that perhaps ought to crop up more frequently. The graphics are colorful, the music lovely, the company you keep more often than not charming. It’s disarmingly engaging just to wander around and talk to people.

Underneath the pleasantness, not so much undercutting it as giving it more texture, is a note of melancholy. This adventure in Britannia takes place many years after the Avatar’s previous ones, and the old companions in adventure who make up his party are as enthusiastic as ever, but also a little grayer, a little more stooped. Meanwhile other old friends (and enemies) from the previous games are forever waiting in the wings for one last cameo. If a Britannia scoffer like me can feel a certain poignancy, it must be that much more pronounced for those who are more invested in the setting. Today, the valedictory feel to Ultima VII is that much more affecting because we know for sure that this is indeed the end of the line for the classic incarnation of Britannia. The single-player series wouldn’t return there until Ultima IX, and that unloved game would alter the place’s personality almost beyond recognition. Ah, well… it’s hard to imagine a lovelier, more affectionate sendoff for old-school Britannia than the one it gets here.

The writing team loves to flirt with the fourth wall. Fortunately, they never quite take it to the point of undermining the rest of the fiction.

Yet even as the game pays loving tribute to the Britannia of yore, there’s an aesthetic sophistication about it that belies the series’s teenage-dungeonmaster roots. It starts with the box, which, apart from the title, is a foreboding solid black. The very simplicity screams major statement, like the Beatles’ White Album or Prince’s Black Album. Certainly it’s a long way from the heaving bosoms and fire-breathing dragons of the typical CRPG cover art.

When you start the game, you’re first greeted with a title screen that evokes the iconic opening sequence to Ultima IV, all bright spring colors and music that smacks of Vivaldi. But then, in the first of many toyings with the fourth wall, the scene dissolves into static, to be replaced by the figure of the Guardian speaking directly to you.

As you wander through Britannia in the game proper, the Guardian will continue to speak to you from time to time — the only voice acting in the game. His ominous presence is constantly jarring you when you least expect it.

The video snippet below of a play within the play, as it were, that you encounter early in the game illustrates some more of the depth and nuance of Ultima VII‘s writing. (Needless to say, this scene in particular owes much to Raymond Benson’s theatrical background.)

This sequence offers a rather extraordinary layer cake of meanings, making it the equal of a sophisticated stage or film production. We have the deliberately, banally bad play put on by the Fellowship actors, with its “moon, June, spoon” rhymes. Yet peeking through the banality, making it feel sinister rather than just inept, is a hint of cult-like menace. Meanwhile the asides of our companions tell us not only that the writers know the play is bad, but that said companions are smart enough to recognize it as well. We have Iolo’s witty near-breaking of the fourth wall with his comment about “visual effects.” And then we have Spark’s final verdict on the passion play, delivered as only a teenager can: “This is terrible!” (For some reason, that line makes me laugh every time.) No other game of 1992, with the possible exception only of the text adventure Shades of Gray, wove so many variegated threads of understanding into its writing. Nor is the scene above singular. The writing frequently displays the same wit and sophistication as what you see above. This is writing by and for adults.

The description of Ultima VII‘s writing as more adult than the norm also applies in the way in which the videogame industry typically uses that adjective. There’s a great extended riff on the old myths of unicorns and virgins. The conversation with a horny unicorn devolves into speculation about whether the Avatar himself is, shall we say, fit to ride the beast…

For all of the cutting-edge programming that went into the game, it really is the writing that does the bulk of the heavy lifting in Ultima VII. And it’s here that this early million-dollar computer game stands out most from the many big-budget productions that would follow it. Origin poured a huge percentage of that budget not into graphics or sound but into content in its purest form. If not the broadest world yet created for a computer at the time of the game’s release, this incarnation of Britannia must be the deepest and most varied. Nothing here is rote; every character has a personality, every character has something all her own to say. The sheer scale of the project which Raymond Benson’s team tackled — this game definitely has more words in it than any computer game before it — is well-nigh flabbergasting.

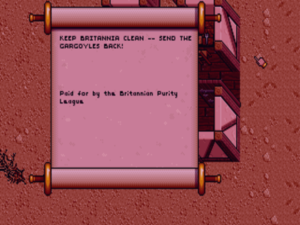

Further, the writers have more on their minds than escapist fantasy. They use the setting of Britannia to ponder the allure of religious cults, the social divide between rich and poor, and even the representation of women in fantasy art, along with tax policy, environmental issues, and racism. The game is never preachy about such matters, but seamlessly works its little nuggets for thought into the high-fantasy setting. Ultima VII may lack the overriding moral message that had defined its three predecessors, but that doesn’t mean it has nothing to say. Indeed, given the newfound nuance and depth of the writing, the series suddenly has more to say here than ever before.

Because of how much else there is to see and do, the main plot about the Guardian sometimes threatens to get forgotten entirely. But it’s enjoyable enough as such things go, even if its main purpose often does seem to be simply to give you a reason to wander around talking to people. In the second half of the game, the plot picks up steam, and there are a fair number of traditional CRPG-style quests to complete. (There are also more personal “quests” among the populaces of the towns you visit, but they’re largely optional and hardly earth-shattering. They are, however, often disarmingly sweet-natured: getting the shy lovelorn fellow together with the girl he worships from afar… that sort of thing.) The game as a whole is very soluble as long as you take notes when you’re given important information; there’s no trace of a quest log here.

While a vocal minority of Ultima fandom decries this seventh installment for the perfectly justifiable reasons I mentioned earlier in this article, the majority laud it as — forgive the inevitable pun! — the ultimate incarnation of what Richard Garriott began working toward in the late 1970s. Even with all of its annoying aspects, it’s undoubtedly the most accessible Ultima for the modern player, what with its fairly intuitive mouse-driven interface, its reasonably attractive graphics and sound, and its relatively straightforward and fair main quest. Meanwhile its nuanced writing and general aesthetic sophistication are unrivaled by any earlier game in the series. If it’s not the most historically important of the main-line Ultima games — that honor must still go to the thematically groundbreaking Ultima IV — it’s undoubtedly the one most likely to be enjoyed by a player today.

Indeed, it’s been called the blueprint for many of the most popular epic CRPGs of today — games where you also spend much of your time just walking around and talking to a host of more or less interesting characters. That influence can easily be overstated, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t something to the claim. No other CRPG in 1992, or for some time thereafter, played quite like this one, and Ultima VII really does have at least as much in common with the CRPGs of today as it does with its contemporaries. On the whole, then, its hallowed modern reputation is well-earned.

Richard Garriott (far left) and the rest of the Ultima VII team toast the game’s release at Britannia Manor, the former’s Austin mansion.

Its reception in 1992, on the other hand, was far more mixed than that reputation might suggest. Questbusters magazine, deploying an unusually erudite literary comparison of the type of which Raymond Benson might have approved, called it “the Finnegans Wake of computer gaming — a flawed masterpiece,” referring to its lumpy mixture of the compelling and the tedious. Computer Gaming World‘s longtime adventure reviewer Scorpia had little good at all to say about it. Perhaps in response to her negativity, the same magazine ran a second, much more positive review from Charles Ardai in the next issue. Nevertheless, he began by summing up the sense of ennui that was starting to surround the whole series for many gamers: “Many who were delighted when Ultima VI was released can’t be bothered to boot up Ultima VII, as though it goes without saying that the seventh of anything can’t possibly be any good. The market suddenly seems saturated; weary gamers, sure that they have played enough Ultima to last a lifetime, eye the new Ultima with suspicion that it is just More Of The Same.” Even at the end of his own positive review, written with the self-stated goal of debunking that judgment, Ardai deployed a counter-intuitive closing sentiment: “After seven Ultimas, it might be time for Lord British to turn his sights elsewhere.”

Not helping the game’s reception were all of the technical problems. It’s all too easy to forget today just how expensive it was to be a computer gamer in the early 1990s, when the rapid advancement of technology meant that you had to buy a whole new computer every couple of years — or less! — just to be able to play the latest releases. More so even than its contemporaries, Ultima VII pushed the state of the art in hardware to its limit, meaning that anyone lagging even slightly behind the bleeding edge got to enjoy constant disk access, intermittent freezes of seconds at a time, and the occasional outright crash.

And then there were the bugs, which were colorful and plentiful. Chunks of the scenery seemed to randomly disappear — including the walls around the starting town of Trinsic, thus bypassing the manual-lookup scheme Origin had implemented for copy protection. A plot-critical murder scene in another town simply never appeared for some players. Even worse, a door in the very last dungeon refused to open for some; Origin resorted to asking those affected to send their save file on floppy disk to their offices, to be manually edited in order to correct the problem and sent back to them. But by far the most insidious bug — one from which even the current edition of the game on digital-download services may not be entirely free — were the keys that disappeared from players’ inventories for no apparent reason. Given what a nightmare keeping track of keys was already, this felt like the perfect capstone to a tower of terribleness. (One can imagine the calls to Origin’s customer support: “Now, did you take all of the stuff out of all of your packs and sort it out carefully on the ground to make sure your key is really missing? What about those weeks-old leeks down there at the bottom of your pack? Did you look under them?”) Gamers had good cause to be annoyed at a product so obviously released before its time, especially in light of its astronomical $80 suggested retail price.

A Computer Gaming World readers’ poll published in the March 1993 issue — i.e., exactly one year after Ultima VII‘s release — saw it ranked as the respondents’ 30th favorite current game, not exactly a spectacular showing for such a major title. Wing Commander II, by way of comparison, was still in position six, Ultima Underworld — which was now outselling Ultima VII by a considerable margin — in a tie for third. It would be incorrect to call Ultima VII a flop, or to imply that it wasn’t thoroughly enjoyed by many of those who played it back in the day. But for Origin the facts remained when all was said and done that it had sold less well than either of the aforementioned two games after costing at least twice as much to make. These hard facts contributed to the feeling inside the company that, if it wasn’t time to follow Charles Ardai’s advice and let sleeping Ultimas lie for a while, it was time to change up the gameplay formula in a major way. After all, Ultima Underworld had done just that, and look how well that had worked out.

But that discussion, of course, belongs to history. In our own times, Ultima VII remains an inspiring if occasionally infuriating experience well worth having, even if you don’t normally play CRPGs or couldn’t care less about the lore of Britannia. I can only encourage all of you who haven’t played it before to remedy that while you wait for my next (and last) article about the game, which will look more closely at the Fellowship, a Britannian cult with an obvious Earthly analogue.

(Sources: the book Ultima: The Avatar Adventures by Rusel DeMaria and Caroline Spector; Origin Systems’s internal newsletter Point of Origin dated August 7 1991, October 25 1991, December 20 1991, February 14 1992, February 28 1992, March 13 1992, April 20 1992, and May 22 1992; Questbusters of July 1991 and August 1992; Computer Gaming World of April 1991, October 1991, August 1992, September 1992, and March 1993; Compute! of January 1992; online sources include The Ultima Codex interviews with Raymond Benson and Brian Martin, a vintage Usenet interview with Richard Garriott, and Sheri Graner Ray’s recollections of her time at Origin on her blog.

Ultima VII: The Black Gate is available for purchase on GOG.com. You may wish to play it using Exult instead of the original executable. The former is a free re-implementation of the Ultima VII engine which fixes some of its worst annoyances and is friendly with modern computers.)

Casey Nordell

February 15, 2019 at 5:10 pm

By this time we had reached peak Ultima. As you note, we have the “best written Ultima ever” in U7 and the “most playable Ultima ever” in UW. These were good times and I remember them well. Thanks so much for writing this and the Underworld articles.

Slashing Dragon

February 15, 2019 at 8:22 pm

Awesome article. Thank you!

To me, this started the downfall of the Ultima series, where the push to break technology boundaries finally led to a loosely designed game with varying quality of subsystems that were not very well integrated, a fancy walking simulator but a game which made it really hard to have fun with.

Steve

February 15, 2019 at 8:42 pm

“Given a choice between sitting down to make a computer game or throwing one of his signature birthday bashes or Halloween spook houses — or, for that matter, merely playing the wealthy young gentleman-about-town in Austin high society more generally — one suspects that Garriott would opt for one of the latter every time.”

A very prophetic statement about Richard Garriott because one of the main criticisms of his current Ultima-like project, Shroud of the Avatar, is that he has little to no involvement with the game itself and instead spends most of his time enjoying his celebrity status.

jacen

February 15, 2019 at 8:43 pm

“Yet peaking through the banality”

Peeking? Ugh, English, why you so hard

Jimmy Maher

February 15, 2019 at 9:00 pm

Sigh. That’s a mistake I make constantly. Thanks!

typolice

February 16, 2019 at 4:32 am

One more: “meat to feet my hungry lot”

Jimmy Maher

February 16, 2019 at 7:14 am

Thanks!

Ricky Derocher

February 15, 2019 at 8:55 pm

“…and quite possibly the most expensive computer game anyone had yet made. Just after its release, Richard Garriott claimed that it had cost $1 million to make, the first time to my knowledge that that milestone figure was associated with any game”.

Space Quest IV was released in March 1991 – and “the game cost over US$1,000,000 to produce”.

Jimmy Maher

February 15, 2019 at 9:01 pm

My knowledge appears to be incomplete. ;) Do you have a source on that quote?

Ricky Derocher

February 15, 2019 at 9:50 pm

I know that I saw the tidbit in other places before, but after Googling for a bit, I can’t find a source other that the Wikipedia article for Space Quest IV.

Anyways, Sierra’s King’s Quest V (released in 1990) cost over a million to produce. According to the King’s Quest Collection Series manual – “It was Sierra’s first million-dollar-plus production effort”.

http://www.sierrahelp.com/Documents/Manuals/Kings_Quest_-_Collection_Series_-_Manual.pdf

SQ IV probably broke the million mark as well, since it was developed around the same time and Sierra was starting to up their graphics to VGA, etc. Sorry, that I can’t find a more definite source than Wikipedia. :-(

Jimmy Maher

February 15, 2019 at 10:30 pm

I had thought King’s Quest V came close, but came in around $800,000. But the issue is murky enough that I excised the claim from the article. Thanks!

whomever

February 15, 2019 at 9:12 pm

You mention music, but I want to just emphasize that IMHO this was probably the game that really justified the MT-32. IMHO Dana Glover did a great job (for the time at least) and especially the use of thematic elements. I still remember the fellowship theme to this day.

Also you mention this but the “this is like no other Ultima” bit really does work; the slightly dark edge, the feeling that something has gone wrong with Britannia (which to be fair U5 also did but this was in may ways darker), the Guardian as this mysterious figure…18 year old me absolutely loved this game. And of course the open world you can just wander about and find the tiny details (the crashed Kilrathi ship!) and ignore the plot completely.

That said I guess I was lucky not to run into the bugs, because I did hear about them. Was this the beginning of Origin’s rather strong mid-90s reputation for rather, ah, lax QA I wonder? Also agreed that this (Ok, Serpent’s Isle) is the end of Ultima; much like Highlander sequels it’s better to ignore anything that came after, Though I actually would be curious to read an article about just WHY Ultima VIII was such a disaster, including the bugs, terrible story line, and really everything else.

Jimmy Maher

February 15, 2019 at 10:37 pm

Yeah, that should make for an interesting research project, and hopefully an interesting article!

stepped pyramids

February 16, 2019 at 7:30 pm

Serpent’s Isle is interesting in that it takes both the virtues and flaws of Black Gate and amplifies them. It has better writing and a more interesting plot, but it’s even buggier and clearly suffered badly from budget and time constraints, resulting in an extremely plot-light third act that is mostly a bunch of busywork. It’s still my favorite game in the series, closely followed by Martian Dreams.

SI is also pretty notable for being one of the earlier signs of western RPGs favoring tighter plotting and character development over nonlinearity. You could remake it in RPG Maker and it’d almost play better as a JRPG.

Jimmy Maher

February 17, 2019 at 12:00 pm

Will have a lot more to say about Serpent Isle in my article on that game proper, but I can’t agree that the writing is better. While not *bad* for the genre, it’s much less textured and much more reliant on epic-fantasy cliches. On the other hand, Serpent Isle is arguably a more varied and interesting *game*, giving you a lot more to actively do — at least until it slowly begins to go off the rails about the time you make it to the Frozen North.

Infinitron

February 17, 2019 at 6:07 pm

The crucial thing about Serpent Isle is that everything you said about Black Gate being a valedictory tribute is even more true with regard to Serpent Isle. The game is a lovely piece of fan service. Somebody who doesn’t care much about the series’ lore wouldn’t get as much out of it, of course.

stepped pyramids

February 17, 2019 at 6:17 pm

There’s just a lot about the texture in Black Gate that doesn’t really work for me. It kind of annoys me, for instance, that they managed to find the time to put an absolutely endless Laurel and Hardy homage into the game but not to add any new dialogue for Lord British as you unravel the plot. LB is so passive and useless in VII that he’s almost a villain. (Even pre-Batlin, it sure seems like he’s let Britannia fall into decline.)

Black Gate also has a lot of variability between areas in terms of quality of dialogue. Paws and Serpent’s Hold almost don’t feel like they’re from the same game. If the rest of the game had a tone consistent with Paws I’d hold the writing in much higher regard. But nah, let’s have the Avatar crack the mystery of the naked people in the bee cave.

That said, there’s a lot of stuff I do really enjoy about Black Gate’s writing. Batlin is fantastic. The gargoyles are good and tragic. Owen the legendary shipwright is a fun little subquest. The mage madness and the cube dialogue is a great example of dialogue updating with plot (in contrast to British). It’s not bad — it’s really quite good — but it’s overstuffed and wordy enough that I start finding myself asking “what exactly are they expecting me to get out of this conversation?”

Jimmy Maher

February 17, 2019 at 6:33 pm

Reasonable points all. I agree that the Laurel and Hardy thing is nowhere near as funny as somebody on the writing team thinks it is. As one of the funniest writers ever once put it, “Brevity is the soul of wit.”

State-tracking is another area where Ultima VII leaves something to be desired, and which I was initially tempted to complain about in the article. Combined with the fact that it’s sometimes hard to know which situations in the towns you can actually affect and which you cannot, it can spawn considerable confusion when the dialog doesn’t update to reflect your actions. I suppose I’m willing to cut the game some slack here, as in so many others areas, because a) I know how all too well really, really hard this sort of thing is to implement and b) no one had ever tried to do anything quite like Ultima VII before.

The dialog in Serpent Isle, however, does generally do a better job of reflecting the current state of the game — perhaps because there’s somewhat less of it for each character.

Bmp

February 15, 2019 at 10:42 pm

As usual, a fine article!

It feels like Ultima VII is somewhere between an RPG and an Adventure game. A couple of situations took advantage of the world simulation, such as following the mayor of Britain after nightfall to uncover his secret tryst. You can interact with all the items in the world, not just a few of them. If I remember correctly, there were a couple of puzzles that could be solved in an intuitive and “systemic” way, utilising the engine’s simulation. Very different from the puzzles in classic LucasArts Adventures where you pick up all of the items and combine them in preposterous ways (“use rubber chicken on hook”).

If you imagine Ultima VII with all the combat removed (the player character is weak or prefers to sneak), and with more puzzles that can be solved in multiple intuitive systemic/simulationist ways, plus some dialog puzzles and choices and consequences, wouldn’t you arrive at a new genre, the Systemic Explorative Open World Adventure game?

Are there any games like that?

Joshua

February 16, 2019 at 1:25 am

The upcoming Disco Elysium!

Chris Floyd

February 16, 2019 at 2:48 am

I would argue that’s what Martian Dreams and Savage Empire are! Open world adventure games powered by an RPG engine that all but ignore character progression and minimize combat.

Bmp

February 16, 2019 at 9:05 am

I played Martian Dreams and thought it was similar to Ultima VII in this respect. The player is sent on a lot of fetch quests while the puzzles are few and rather simple, which is normal for RPGs. It still has one foot on the RPG side.

What I envision is something different, a game where combat and a couple of other RPG trappings have been completely removed and where puzzles take center stage, like in true Adventure games, but are to be solved by utilising the game’s simulation engine.

Pedro Timóteo

February 16, 2019 at 10:42 am

Trespasser?

(you didn’t mention that it had to be *good*…)

Bmp

February 16, 2019 at 12:38 pm

:) Trespasser was interesting. I only played the demo, and I remember some challenges that had to be solved by using the (wonky) physics systems.

Now physics systems do provide natural, intuitive, systemic solutions to problems, yes. But if the designers want to provide a large amount of different puzzles, they soon have to set up unrealistic contraptions (see Half-Life 2).

What the Antiquarian didn’t expand upon is that Ultima VII has a world that is simulated to an unsurpassed amount of detail. Not only can the player interact with all the items in the world, the NPCs do that too when they follow their daily schedules. For example, the street lamps in the cities are lit one by one by a lantern lighter NPC doing his rounds. Are there any other games at all that do something like this? (Aside from Dwarf Fortress, which probably also simulates the chance of the dwarf’s beard catching fire in the process.)

These simulation aspects are the ones that I think can be exploited for systemic adventure game puzzles. After all, isn’t it a large part of a detective’s work to be at the right place at the right time, to witness people interacting with items and other persons?

(These simulation details in Ultima VII are not central to the game experience, so I don’t mind that it’s not a larger part of the article. The mention of trading meat at different prices shows one aspect of the simulation detail. While these details are not central to the game, I think they lend a lot of credibility to the game’s world, which I miss in games like Baldur’s Gate.)

Jimmy Maher

February 16, 2019 at 2:59 pm

I have a bit of a contrary view on Ultima VII’s much-vaunted “simulated world.” In fact, I cut a fairly long discourse on the subject from the article, after having decided that it already has enough negativity toward a game I actually really like. I don’t think it goes that much further in this area than Ultima VI, and a lot of it strikes me as development time that could have been better spent elsewhere, given the problems with inventory management and combat. Baking bread — to choose the most oft-cited example — is neat, but what’s it really good for? It’s far too tedious a process to actually be used as a regular source of food.

Further, I find that the degree of world simulation is quite inconsistent. The things you can do tend to raise my expectations, only to be disappointed at the many things — most things, really — that you *can’t* do. I remember, for instance, struggling for quite some time in the blacksmith’s shop in Trinsic, trying to figure out how to use the forge and all of those sword blanks to make new weapons for my party.

Ironically, the Ultima that went the farthest in the world-simulation/crafting department was one of the least heralded: Savage Empire, which let you do things like make your own rifles out of saltpaper, bamboo, and rocks. Now, *that* was useful! ;)

Martin

February 18, 2019 at 1:24 am

Saltpeter?

Andrew

March 24, 2019 at 7:43 am

My god how long I spent trying to make weapons in Trinsic.

“What am I doing wrong?!”

“Maybe 10 pumps of the bellows instead of 8”

“Maybe I didn’t leave it in the coals long enough.”

“Do I need to hold the hammer and tongs?”

“Alright maybe 20 pumps of the bellows.”

Etc.

Etc.

Etc.

Terilem Dragon

February 16, 2019 at 10:41 am

Another excellent article! Each one is an event and I’m looking forward to the deep dive into the Fellowship.

Just a small note: “Michael Pierce” is a misnomer in the October ’91 CGW; they meant Micael Priest, who was a prominent poster artist in the Austin music scene before joining Origin. Sadly, he passed away just last September.

Jimmy Maher

February 16, 2019 at 3:05 pm

Thanks so much for the correction!

Rikkles

February 16, 2019 at 1:37 pm

At the time I’d played every single Ultima since U2 at time of its release. My favorite was and still is U5, because U7’s tech simply tried to outpace itself and hurt an otherwise brilliant story and environment.

Maybe also it’s because after having fought tooth and nail against all the problems so well described in the article that, in the last dungeon of the game, so close to victory, I was thwarted by that big black closed metal panel.

The fact that I still remember it 26 years later is something worthy of a psych thesis

Allan Holland

March 14, 2019 at 9:46 am

The fact that you remember the trauma of a game experience speaks to the immense cultural and interpersonal influences games had become by 1992. It makes you a member of this tribe for whom some perspective(s) of life were influenced or shaped by computer gaming. I confess I never solved the last riddle of Ultima 4, to my private soul-scorching shame. Couldn’t kill L’Kbreth at the end of Wizardry 3 either.

Infinitron

February 16, 2019 at 3:59 pm

“Further, the writers have more on their minds than escapist fantasy. They use the setting of Britannia to ponder the allure of religious cults, the social divide between rich and poor, and even the representation of women in fantasy art, along with tax policy, environmental issues, and racism. ”

You could probably write a pretty interesting article just about Ultima VII’s politics. The era of politics it represents, how it differs from ours.

Narsham

February 16, 2019 at 5:59 pm

I am amazed to learn that, as I was reading this article, I am STILL mad at Ultima VII. It came out at about the time that I was going to college, and I went from disliking how it was wasting my time to active hatred of a sort no other game has managed to provoke. I think the presence of the Internet and its varied resources are part of the explanation: when U7 came out, magazines were your best information source and you couldn’t look up all the discussions of game-breaking bugs and “features” that build frustration. I loved the other Ultimas and had versions of them for three different computer systems, so U7 was a first-day purchase for me.

After purchasing and installing, I had to spend nearly an hour tinkering with my config.sys and autoexec.bat to get the game to run; U7 was my only game that had its own boot-menu item. After initial start-up and adjustment to the mouse/visual structures of the game (I loved keyboard shortcuts and am not very visual as a person), I got into the starting mystery of the game and was closing in on that phenomenon where you want to get back to playing whenever you aren’t, when I hit a stopping point in solving the murder. I’d worked out all the details, but could figure out what I needed to do to trip the next step in the quest; the game wouldn’t give me any dialogue options to demonstrate that I’d worked through things. Without access to online help, I decided that I had to run down the murderer to advance the smaller quest, not know that that was part of a larger quest. So I stocked up on food, bought missile weapons for my companions (as, since U3, missile weapons were your best choice, and they were basically mandatory if you used the U6 AI), and hit the road.

Cue my companions starving despite having food. In their packs. This was not just busywork, it was busywork that involved that damn inventory management. I started getting angry at this point. What was next, having outhouses in the game and making your companions explode if you didn’t have them go potty every few days?

Then cue a random combat encounter. I can’t control my companions, who nearly kill me, and as I’m clicking around trying to attack the screen keeps flashing blood-red, making things even more chaotic. I always loved the tactical side of RPGs. This was an insult.

The last straw was coming across a small dungeon. I figured I might not be strong enough to explore a dungeon yet, so I saved before proceeding. The first room had some obvious floor traps; concerned about the pathing, I carefully clicked “tile” by “tile” into the room. I think I’d passed the second trap successfully when my companions, who were dancing circles around me in real time, triggered every single trap in the room, killing us all.

That wasn’t the last straw. The last straw was the Guardian taunting me for the total party kill. The game killed me thanks to its own limitations, and then insulted me for getting killed.

And I haven’t touched U7 since.

Narsham

February 16, 2019 at 6:00 pm

” I’d worked out all the details, but could figure out what I needed to do to trip the next step in the quest…” should be “could NOT.”

Jimmy Maher

February 16, 2019 at 6:08 pm

Interesting. The game shouldn’t have allowed you to leave the starting town without solving the murder. I wonder if you got hit by the “disappearing town walls” bug.

Jeremy Reimer

February 16, 2019 at 6:44 pm

I have a somewhat more positive impression of Ultima 7. To me it represented a living, breathing world that subsequent RPGs, even with their sumptuous 3D graphics, have failed to reach.

The “baking bread” example is the most oft-cited one, but I never spent any time baking bread. What I loved to do more was to go into towns and watch the NPCs as they went about their daily lives. They didn’t just stand behind a shop counter all day. They would wake up in the morning, open up the shutters, walk around admiring or cursing the weather, then go to their day job. After work was over they would head to the inn, sit at the table and order food. The barmaid would take the order and place actual in-game food items on their plate.

I found that if you used the mouse to move this food from one plate to another, the NPCs would immediately stand up, yell at you for stealing, walk around a bit, then eventually sit back down at the NEW PLACE SETTING where you had put their food. Then they would continue to eat. If you did this too much they might even get mad enough to attack you.

None of this was necessary for the game. But it made Britannia seem like a real PLACE, rather than just a bunch of static NPCs to click on and get fetch quests from.

Yes, it was annoying that you couldn’t forge swords at the forge from the blacksmith’s blanks. But if you took a bunch of crates from all over town and stacked them up outside the blacksmith’s house in Trinsic in a solid staircase-like fashion, you could climb up to the roof and find (and loot) a secret room full of magical armor. Only enough to equip your main character, but a nice boost at the beginning of the game. Not to mention the amazing sidequest to find the magical “Hoe of Destruction!”

Yes, the combat was janky, the inventory management frustrating, and the bugs terrifying. But the story, the writing, and the world building were incredible. Ultima VII is easily in my top five best games of all time.

Mike Taylor

February 18, 2019 at 12:56 pm

“Yes, the combat was janky, the inventory management frustrating, and the bugs terrifying. But …”

Let me stop you there :-)

Aula

February 16, 2019 at 7:00 pm

“not so much undercutting it is as giving it more texture”

that “is” shouldn’t be there

“is that much affecting because”

should be “that much more affecting”

“This sequences offers”

should be singular “sequence”

“or for some thereafter”

some what thereafter? time? years?

Jimmy Maher

February 16, 2019 at 7:48 pm

Thanks!

stepped pyramids

February 16, 2019 at 7:37 pm

Dallas Snell, like many other Origin employees, got a somewhat plot-relevant cameo in the game. Although many of the other cameos are not exactly flattering (Benson wrote himself in as a hyper-egotistical playwright), Snell’s cameo could easily be read to have some implications about his management style.

http://wiki.ultimacodex.com/wiki/De_Snel

Funny to compare this to Warren Spector’s extremely flattering appearance in Martian Dreams.

Jrd

February 16, 2019 at 8:11 pm

Pretty sure U7 does track a “karma” level, and your companions can leave (and I think even attack?) you if it drops too low from stealing or what have you. Also, I seem to remember that the food thing can be largely mitigated by using a “create food” spell that it is super cheap both in terms of casting cost and reagents, so there’s a simple opt-out of that tedium.

Jimmy Maher

February 17, 2019 at 11:51 am

Does it really track petty theft of food sitting out in the open? I know it keeps track of whether you actively break into people’s chests and the like, or, God forbid, starting running around killing random people, but I didn’t think it cared about more piddly crimes.

The create food spell is kind of annoying in that it often only creates a piece of fruit or the like that won’t keep your people satisfied very long at all. And you still have to collect reagents for it, even if it is cheap in that respect, and cast it over and over, then feed the resulting food manually to everyone. Still pretty tedious in my experience. ;)

stepped pyramids

February 17, 2019 at 5:59 pm

Ultima VII doesn’t have karma, but companions might get angry if they witness you committing a crime. And petty theft absolutely counts. I remember once I got Iolo to quit in a huff because I stuffed some grapes down his throat.

Jimmy Maher

February 17, 2019 at 6:26 pm

Okay. Excised that bit about the lack of consequences. Thanks!

Pedro Quaresma

February 19, 2019 at 3:06 pm

On the other hand, the engine lets you steal without consequences if you know what you’re doing.

1) Drag an item into your inventory? Theft

2) Open your inventory first (pausing the game) and then drag an item into it? Nobody notices

Jonathan Badger

February 17, 2019 at 1:54 am

“Ultima VII is my third favorite game to bear the Ultima name, behind only Martian Dreams and the first Ultima Underworld.”

Well, well. I remember that in the discussion of Ultima VI that I and others encouraged you to check out Martian Dreams which you hadn’t played at the time. I’m glad that not only did you eventually do so, but that it managed to become one of your top three Ultimas!

Jimmy Maher

February 17, 2019 at 12:56 pm

Indeed. Thanks again for that!

NotTseramed

February 17, 2019 at 1:56 am

The CRPG Book Project’s Ultima VII review has a nice quote from Raymond Benson:

“In many ways, The Black Gate was one of the very first SIMS! That was the genius behind the engine that was created by Richard [Garriott] and Ken Demarest (lead programmer) and his team. That was the idea – to create a world you could run around in and live in. The other writers and I took great care to make each individual NPC a whole person, as much as we could.”

The developers certainly succeeded in creating a living world as Ultima VII and Serpent Isle are the most immersive games I’ve ever played.

Infinitron

February 17, 2019 at 1:18 pm

That’s actually a quote from Kenneth Kully’s interview with Benson: https://ultimacodex.com/interviews/we-wanted-the-game-to-last-forever-an-interview-with-raymond-benson/

Adamantyr

February 17, 2019 at 7:17 pm

An excellent article! I’ve found all your Ultima articles to be very informative and far less biased. (Thinking Shay Addams Book of Ultima which largely portrays Garriott as a perfect visionary.)

I first saw Ultima VII on a friend’s PC, and was completely fascinated with it. I think you nailed it that it’s more a simulation than anything, which is why it’s so popular even today. As a game, well… Combat’s a mess, inventory management a pain, and the fact that some items in game are “temporary” and others are “permanent” is likely a big cause of the bugs people encountered.

For example, there is typically a group of bandits that spawn right outside of west Britain, on the road to Yew and Skara Brae. I once got a chest off one of them and I took it back to the castle and used it to store some stuff in my private room. Guess what happened? The chest disappeared. I learned my lesson from that, which is only use containers that pre-existed in the world. I get why it happened of course; there’ s finite item count in the game and they had to do something to “clean up” items.

On the subject of the first $1 million game, Chris Crawford claims (or lays the blame) on Wing Commander for changing the industry for the worse. (Source is an interview with Richard Rouse III, published in Game Design: Theory & Practice)

Paul

February 18, 2019 at 1:52 pm

I’m extremel surprised that one word doesn’t even show up on the page, nor in the comments, that I would very much have expected to do so: sandbox.

U7 was the first real sandbox CRPG, anticipating much of what makes modern CRPGs the experience they are. Maybe you could call U6 the first, but U7 really took it to the next level. In every town there’s something to do that’s not about the main quest in any way, from basic things like finding a lost locket to having the most esteemed artist/inventor/engineer commit suicide for being a buffoon with good PR! There’s just so much stuff to discover while wandering around, pirate caves, hermits, the infamous nudists in Bee Cave… want to play Knight’s Bridge at Nystul’s for a while? Or maybe go on a dragonslaying spree in Destard? Get a good laugh out of “X marks the spot” treasure? Loot the mighty Hoe of Destruction from a Cove farmer’s shed? What about piecing together the insidious plot to murder Lord British involving a powerful terrorist cell operating out of Despise? It’s all there, all fully realized, all lovingly crafted and placed on the map by hand, no Radiant algorithms or similar shite involved.

THAT’s what made me return to U7 after my first (and second…) playthrough!

Kai

February 18, 2019 at 7:41 pm

That’s the article I’ve been waiting for since the day I discovered The Digital Antiquarian. Naturally, I need to savour the moment for a while before actually reading it.

Suffice to say that U7 was the first Ultima I played (pretty much the first DOS game, too, given I was heavily invested into the Amiga at that time), and in my view it was the best. It still beats most modern RPGs by leagues (my latest playthrough was 2 years ago), but then perhaps I look for different things in a game than most. Anyway, I’ll need to reserve some time for reading and commenting in depth.

Kai

February 19, 2019 at 7:49 pm

Great article, as always, and one that does the subject justice.

Though as with some other people here, I never really perceived any of the apparent “flaws” as something inherently bad, even when playing the game for the first time. For one, I had not bought it at release, but in form of The Complete Ultima VII, so I had a mostly bug free version running on hardware more than up to the task. Also, having had no former experience with Ultima (I knew it from hearsay, only), I did not have any specific expectations, but I found a game world that was oozing with the history accumulated over the course of the six previous installments. Neither combat, food nor inventory bothered me much (honestly, the Avatar’s backpack was likely more tidy than my room at any given time). Nowadays, I still enjoy the (lack of tedious) combat, and Exult is a godsend with the keyring and the ‘F’ key. (As for acquiring food, partaking at the free dinner served at the palace usually keeps everyone fed for the day)

The thing is, Ultima VII did really deliver a virtual world that is largely unrivaled by any game that came since. Be it the world itself, the NPCs, the interactivity; I find it hard to name other games that shine in all those aspects (TES III delivered in terms of world-building, unlike its successors, but fell flat in other regards. Kingdom Come: Deliverance is getting close, but after all those years, shouldn’t we finally have something that surpasses Ultima VII?)

For me, this only leaves one conclusion: if Ultima VII is to sandbox games what Dungeon Master is to realtime blobbers, what you said about DM must apply here as well: “None of the real-time blobbers that came after Dungeon Master was clearly better than it; arguably, none was ever quite as good.” As for the why: who knows? Maybe because “Origin poured a huge percentage of [the] budget not into graphics or sound but into content in its purest form”. And that really shows!

Peter W

February 20, 2019 at 11:58 pm

Is there any other game that has a manual written from the point of view of by the bad guy?

Stephen

February 23, 2019 at 12:29 pm

Great article as always. I particularly appreciated the view of the Dallas Snell side of things… the edict to “call it a day by midnight” says so much.

On that note, I was hoping you might cast some light on the apparently satirical references to Electronic Arts which appear in the game (mostly the Tetrahedron / Sphere / Cube Generators). I could never tell whether they were good-humoured joshing or a sign of bitterness at Origin’s new (?) owner (not sure when it was actually acquired?).

Tiny technical quibble: can you say more about what makes the game “unplayable on many post-early-1990s machines”? Am not aware of anything… e.g. I do play Ultima VII fairly often on a c.1999 PC and it’d surprise me if later ones wouldn’t work too. (Of course you do need to slow fast machines down… there is a frame limiter but it has the limit set too high.)

Jimmy Maher

February 23, 2019 at 2:05 pm

The references to Electronic Arts are a legacy of Origin’s time as one of EA affiliated labels, which did not end well. Lots more detail here: https://www.filfre.net/2016/02/the-road-to-v/. I did plan to mention them, but was holding out for the article about EA’s acquisition of Origin in 1993. For now, suffice to say that the references are more bitter than good-natured, although Origin would soon have cause to spin them the other way. They come across as thoroughly petty today. Definitely not one of Richard Garriott’s better moments… I’m pretty sure he was behind them.

I admit to not having much personal experience with the subject, but my understanding is that the Voodoo memory manager turned into a huge problem for playing Ultima VII on later PCs. I believe it’s hopelessly incompatible with even MS-DOS-based versions of Windows, and, because it doesn’t play nice with EMS *or* XMS, pretty much requires a floppy boot disk to run under vanilla MS-DOS. I’ve further heard that it won’t run on many later PCs at all due to assumptions it makes about the memory map which don’t always hold true.

Kisai

June 21, 2023 at 4:28 pm

It wasn’t so much the “Voodoo Memory Manager” but that ANY memory manager (of which EMM386 which was needed to loadhigh TSR’s like the mouse driver to get some of that conventional memory back.) Since this was the era of Windows 3.1, you couldn’t run it under Windows either. Basically it would see the computer was in protected mode and refuse to run. Exult developers basically discovered that Voodoo wasn’t managing much of anything, it was pretty much a flat memory model during an era when that was unheard of.

You pretty much needed a boot disk that only installed the mouse driver and NOTHING else and hope you still had enough conventional memory to actually run Ultima VII.

This problem would carry over into Ultima 7 part 2, and 8 as well if I recall. None of these games ran under Windows 95 at all. Gravis Ultrasound users also were left out in the cold because it took up a lot of memory.

As for the bugs in Ultima VII. I have the 5.25″ floppy version kicking around still, and I would never recommend installing it. Play the GOG/Ultima Collection version that has the Forge of Virtue already in it. Because the “disappearing keys” bug is notorious, as well as other things disappearing. Which knowing about memory management now sounds like the reason the keys and other objects disappearing in the world were because the memory manager was “garbage collecting” the objects when they weren’t visible and I guess “not owned” by you. So keys were intended to disappear (see SI), but lots of other objects were not, like crates, chests, and keys you haven’t used yet. So the only work around in the release version of VII was to stick all the keys in the bag, and leave the bag on the floor when you slept. That side-stepped the “garbage collection”.

However if you thought you were smart by taking crates or chests and leaving them on the cart or magic carpet, they disappeared too. I recall one game where I had like 6 chests on the cart, only to come back and all the crates except the two on the back were gone.

I really liked VII, even given all the bugs at the time, but the show-stopper was the “shake” bug, which on the VGA card I had, would stop updating the drawing of the screen after it happened. (you’d basically see a row of tiles, 8 lines of black, and then the next 8 tiles, and this would repeat after every shake, but it would also stop drawing after the first shake.) I did find a way to “fix it” on that VGA card, because hitting print-screen, with the printer plugged in, would force the screen to refresh. And also waste a bunch of paper. It HAD to be powered on for it to work.

Playing it on DOSBOX now, kinda makes you forget how much of a pain it was getting the original floppy version to work, let alone later CD-ROM versions. Once DOS 6 came out, the option to create a boot menu instead of a boot disk was available, and that solved all the “make a boot floppy” problems. As long as you knew what you were doing.

But the most notoriously buggy CRPG from EA is still Starflight. A game that self-modifies itself, and corrupts it’s own data even under dosbox.

Ethan Johnson

March 2, 2019 at 4:22 pm

Denis Loubet confirmed to me that the EA homage was both intentional and mean-spirited in it’s depiction. They weren’t acquired yet, but they had a breakdown which Jimmy talked about, which seems to primarily been about a personal betrayal that the Garriotts perceived.

Matt

February 23, 2019 at 3:44 pm

I think Ultima VII was the first game to include a genuinely funny bug.

1. Enemies were coded to drop their possessions as they ran away from you.

2. Cows had slabs of beef in their possession, so you could kill them for food.

Hit a cow, and it flees… dropping chunks of itself along the way.

The visual is funny, the effect is benign, and you understand exactly how this mistake occurred (no flag for un-droppable inventory items).

stepped pyramids

February 23, 2019 at 11:41 pm

You can use Pickpocket in Ultima VI to steal meat out of animals, too. And Serpent Isle adds the Vibrate spell, which can knock normally undroppable items (like spell weapons) out of NPCs. Funny stuff!

Sam

May 6, 2019 at 5:14 am