Robyn Miller, one half of the pair of brothers who created the adventure game known as Myst with their small studio Cyan, tells a story about its development that’s irresistible to a writer like me. When the game was nearly finished, he says, its publisher Brøderbund insisted that it be put through “focus-group testing” at their offices. Robyn and his brother Rand reluctantly agreed, and soon the first group of guinea pigs shuffled into Brøderbund’s conference room. Much to its creators’ dismay, they hated the game. But then, just as the Miller brothers were wondering whether they had wasted the past two years of their lives making it, the second group came in. Their reaction was the exact opposite: they loved the game.

So would it be forevermore. Myst would prove to be one of the most polarizing games in history, loved and hated in equal measure. Even today, everyone seems to have a strong opinion about it, whether they’ve actually played it or not.

Myst‘s admirers are numerous enough to have made it the best-selling single adventure game in history, as well as the best-selling 1990s computer game of any type in terms of physical units shifted at retail: over 6 million boxed copies sold between its release in 1993 and the dawn of the new millennium. In the years immediately after its release, it was trumpeted at every level of the mainstream press as the herald of a new, dawning age of maturity and aesthetic sophistication in games. Then, by the end of the decade, it was lamented as a symbol of what games might have become, if only the culture of gaming had chosen it rather than the near-simultaneously-released Doom as its model for the future. Whatever the merits of that argument, the hardcore Myst lovers remained numerous enough in later years to support five sequels, a series of novels, a tabletop role-playing game, and multiple remakes and remasters of the work which began it all. Their passion was such that, when Cyan gave up on an attempt to turn Myst into a massively-multiplayer game, the fans stepped in to set up their own servers and keep it alive themselves.

And yet, for all the love it’s inspired, the game’s detractors are if anything even more committed than its proponents. For a huge swath of gamers, Myst has become the poster child for a certain species of boring, minimally interactive snooze-fest created by people who have no business making games — and, runs the spoken or unspoken corollary, played by people who have no business playing them. Much of this vitriol comes from the crowd who hate any game that isn’t violent and visceral on principle.

But the more interesting and perhaps telling brand of hatred comes from self-acknowledged fans of the adventure-game genre. These folks were usually raised on the Sierra and LucasArts traditions of third-person adventures — games that were filled with other characters to interact with, objects to pick up and carry around and use to solve puzzles, and complicated plot arcs unfolding chapter by chapter. They have a decided aversion to the first-person, minimalist, deserted, austere Myst, sometimes going so far as to say that it isn’t really an adventure game at all. But, however they categorize it, they’re happy to credit it with all but killing the adventure genre dead by the end of the 1990s. Myst, so this narrative goes, prompted dozens of studios to abandon storytelling and characters in favor of yet more sterile, hermetically sealed worlds just like its. And when the people understandably rejected this airless vision, that was that for the adventure game writ large. Some of the hatred directed toward Myst by stalwart adventure fans — not only fans of third-person graphic adventures, but, going even further back, fans of text adventures — reaches an almost poetic fever pitch. A personal favorite of mine is the description deployed by Michael Bywater, who in previous lives was himself an author of textual interactive fiction. Myst, he says, is just “a post-hippie HyperCard stack with a rather good music loop.”

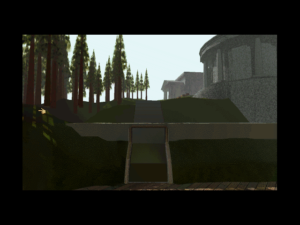

After listening to the cultural dialog — or shouting match! — which has so long surrounded Myst, one’s first encounter with the actual artifact that spurred it all can be more than a little anticlimactic. Seen strictly as a computer game, Myst is… okay. Maybe even pretty good. It strikes this critic at least as far from the best or worst game of its year, much less of its decade, still less of all gaming history. Its imagery is well-composited and occasionally striking, its sound and music design equally apt. The sense of desolate, immersive beauty it all conveys can be strangely affecting, and it’s married to puzzle-design instincts that are reasonable and fair. Myst‘s reputation in some quarters as impossible, illogical, or essentially unplayable is unearned; apart from some pixel hunts and perhaps the one extended maze, there’s little to really complain about on that front. On the contrary: there’s a definite logic to its mechanical puzzles, and figuring out how its machinery works through trial and error and careful note-taking, then putting your deductions into practice, is genuinely rewarding, assuming you enjoy that sort of thing.

At the same time, though, there’s just not a whole lot of there there. Certainly there’s no deeper meaning to be found; Myst never tries to be about more than exploring a striking environment and solving intricate puzzles. “When we started, we wanted to make a [thematic] statement, but the project was so big and took so much effort that we didn’t have the energy or time to put much into that part of it,” admits Robyn Miller. “So, we decided to just make a neat world, a neat adventure, and say important things another time.” And indeed, a “neat world” and “neat adventure” are fine ways of describing Myst.

Depending on your preconceptions going in, actually playing Myst for the first time is like going to meet your savior or the antichrist, only to find a pleasant middle-aged fellow who offers to pour you a cup of tea. It’s at this point that the questions begin. Why does such an inoffensive game offend so many people? Why did such a quietly non-controversial game become such a magnet for controversy? And the biggest question of all: why did such a simple little game, made by five people using only off-the-shelf consumer software, become one of the most (in)famous money spinners in the history of the computer-games industry?

We may not be able to answers all of these whys to our complete satisfaction; much of the story of Myst surely comes down to sheer happenstance, to the proverbial butterfly flapping its wings somewhere on the other side of the world. But we can at least do a reasonably good job with the whats and hows of Myst. So, let’s consider now what brought Myst about and how it became the unlikely success it did. After that, we can return once again to its proponents and its detractors, and try to split the difference between Myst as gaming’s savior and Myst as gaming’s antichrist.

If nothing else, the origin story of Myst is enough to make one believe in karma. As I wrote in an earlier article, the Miller brothers and their company Cyan came out of the creative explosion which followed Apple’s 1987 release of HyperCard, a unique Macintosh authoring system which let countless people just like them experiment for the first time with interactive multimedia and hypertext. Cyan’s first finished project was The Manhole. Published in November of 1988 by Mediagenic, it was a goal-less software toy aimed at children, a virtual fairy-tale world to explore. Six months later, Mediagenic added music and sound effects and released it on CD-ROM, marking the first entertainment product ever to appear on that medium. The next couple of years brought two more interactive explorations for children from Cyan, published on floppy disk and CD-ROM.

Even as these were being published, however, the wheels were gradually coming off of Mediagenic, thanks to a massive patent-infringement lawsuit they lost to the Dutch electronics giant Philips and a whole string of other poor decisions and unfortunate events. In February of 1991, a young bright spark named Bobby Kotick seized Mediagenic in a hostile takeover, reverting the company to its older name of Activision. By this point, the Miller brothers were getting tired of making whimsical children’s toys; they were itching to make a real game, with a goal and puzzles. But when they asked Activision’s new management for permission to do so, they were ordered to “keep doing what you’ve been doing.” Shortly thereafter, Kotick announced that he was taking Activision into Chapter 11 bankruptcy. After he did so, Activision simply stopped paying Cyan the royalties on which they depended. The Miller brothers were lost at sea, with no income stream and no relationships with any other publishers.

But at the last minute, they were thrown an unexpected lifeline. Lo and behold, the Japanese publisher Sunsoft came along offering to pay Cyan $265,000 to make a CD-ROM-based adult adventure game in the same general style as their children’s creations — i.e., exactly what the Miller brothers had recently asked Activision for permission to do. Sunsoft was convinced that there would be major potential for such a game on the upcoming generation of CD-ROM-based videogame consoles and multimedia set-top boxes for the living room — so convinced, in fact, that they were willing to fund the development of the game on the Macintosh and take on the job of porting it to these non-computer platforms themselves, all whilst signing over the rights to the computer version(s) to Cyan for free. The Miller brothers, reduced by this point to a diet of “rice and beans and government cheese,” as Robyn puts it, knew deliverance when they saw it. They couldn’t sign the contract fast enough. Meanwhile Activision had just lost out on the chance to release what would turn out to be one of the games of the decade.

But of course the folks at Cyan were as blissfully unaware of that future as those at Activision. They simply breathed sighs of relief and started making their game. In time, Cyan signed a contract with Brøderbund to release the computer versions of their game, starting with the Macintosh original.

Myst certainly didn’t begin as any conscious attempt to re-imagine the adventure-game form. Those who later insisted on seeing it in almost ideological terms, as a sort of artistic manifesto, were often shocked when they first met the Miller brothers in person. This pair of plain-spoken, baseball-cap-wearing country boys were anything but ideologues, much less stereotypical artistes. Instead they seemed a perfect match for the environs in which they worked: an unassuming two-story garage in Spokane, Washington, far from any centers of culture or technology. Their game’s unique personality actually stemmed from two random happenstances rather than any messianic fervor.

One of these was — to put it bluntly — their sheer ignorance. Working on the minority platform that was the Macintosh, specializing up to this point in idiosyncratic children’s software, the Miller brothers were oddly disengaged from the computer-games industry whose story I’ve been telling in so many other articles here. By their own account, they had literally never even seen any of the contemporary adventure games from companies like LucasArts and Sierra before making Myst. In fact, Robyn Miller says today that he had only played one computer game in his life to that point: Infocom’s ten-year-old Zork II. Rand Miller, being the older brother, the first mover behind their endeavors, and the more technically adept of the pair, was perhaps a bit more plugged-in, but only a bit.

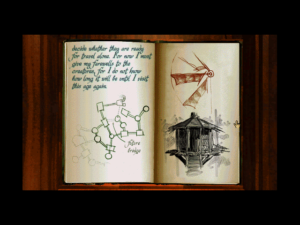

The other circumstance which shaped Myst was the technology employed to create it. This statement is true of any game, but it becomes even more salient here because the technology in question was so different from that employed by other adventure creators. Myst is indeed simply a HyperCard stack — the “hippie-dippy” is in the eye of the beholder — gluing together pictures generated by the 3D modeler StrataVision. During the second half of its development, a third everyday Macintosh software package made its mark: Apple’s QuickTime video system, which allowed Myst‘s creators to insert snippets of themselves playing the roles of the people who previously visited the semi-ruined worlds you spend the game exploring. All of these tools are presentation-level tools, not conventional game-building ones. Seen in this light, it’s little surprise that so much of Myst is surface. At bottom, it’s a giant hypertext done in pictures, with very little in the way of systems of any sort behind it, much less any pretense of world simulation. You wander through its nodes, in some of which you can click on something, which causes some arbitrary event to happen. The one place where the production does interest itself in a state which exists behind its visuals is in the handful of mechanical devices found scattered over each of its landscapes, whose repair and/or manipulation form the basis of the puzzles that turn Myst into a game rather than an unusually immersive slideshow.

In making Myst, each brother fell into the role he was used to from Cyan’s children’s projects. The brothers together came up with the story and world design, then Robyn went off to do the art and music while Rand did the technical plumbing in HyperCard. One Chuck Carter helped Robyn on the art side and Rich Watson helped Rand on the programming side, while Chris Brandkamp produced the intriguing, evocative environmental soundscape by all sorts of improvised means: banging a wrench against the wall or blowing bubbles in a toilet bowl, then manipulating the samples to yield something appropriately other-worldly. And that was the entire team. It was a shoestring operation, amateurish in the best sense. The only thing that distinguished the boys at Cyan from a hundred thousand other hobbyists playing with the latest creative tools on their own Macs was the fact that Cyan had a contract to do so — and a commensurate quantity of real, raw talent, of course.

Ironically given that Myst was treated as such a cutting-edge product at the time of its release, in terms of design it’s something of a throwback — a fact that does become less surprising when one considers that its creators’ experience with adventure games stopped in the early 1980s. A raging debate had once taken place in adventure circles over whether the ideal protagonist should be a blank slate, imprintable by the player herself, or a fully-fleshed-out role for the player to inhabit. The verdict had largely come down on the side of the latter as games’ plots had grown more ambitious, but the whole discussion had passed the Miller brothers by.

So, with Myst we were back to the old “nameless, faceless adventurer” paradigm which Sierra and LucasArts had long since abandoned. Myst actively encourages you to think of it as yourself there in its world. The story begins when you open a mysterious book here on our world, whereupon you get sucked into an alternate dimension and find yourself standing on the dock of a deserted island. You soon learn that you’re following a trail first blazed by a father and his two sons, all of whom had the ability to hop about between dimensions — or “ages,” as the game calls them — and alter them to their will. Unfortunately, the father is now said to be dead, while the two brothers have each been trapped in a separate interdimensional limbo, each blaming the other for their father’s death. (These themes of sibling rivalry have caused much comment over the years, especially in light of the fact that each brother in the game is played by one of the real Miller brothers. But said real brothers have always insisted that there are no deeper meanings to be gleaned here…)

You can access four more worlds from the central island just as soon as you solve the requisite puzzles. In each of them, you must find a page of a magical book. Putting the pages together, along with a fifth page found on the central island, allows you to free the brother of your choice, or to do… something else, which actually leads to the best ending. This last-minute branch to an otherwise unmalleable story is a technique we see in a fair number of other adventure games wishing to make a claim to the status of genuinely interactive fictions. (In practice, of course, players of those games and Myst alike simply save before the final choice and check out all of the endings.)

For all its emphasis on visuals, Myst is designed much like a vintage text adventure in many ways. Even setting aside its explicit maze, its network of discrete, mostly empty locations resembles the map from an old-school text adventure, where navigation is half the challenge. Similarly, its complex environmental puzzles, where something done in one location may have an effect on the other side of the map, smacks of one of Infocom’s more cerebral, austere games, such as Zork III or Spellbreaker.

This is not to say that Myst is a conscious throwback; the nature of the puzzles, like so much else about the game, is as much determined by the Miller brothers’ ignorance of contemporary trends in adventure design as by the technical constraints under which they labored. Among the latter was the impossibility of even letting the player pick things up and carry them around to use elsewhere. Utterly unfazed, Rand Miller coined an aphorism: “Turn your problems into features.” Thus Myst‘s many vaguely steam-punky mechanical puzzles, all switches to throw and ponderous wheels to set in motion, are dictated as much by its designers’ inability to implement a player inventory as by their acknowledged love for Jules Verne.

And yet, whatever the technological determinism that spawned it, this style of puzzle design truly was a breath of fresh air for gamers who had grown tired of the “use this object on that hotspot” puzzles of Sierra and LucasArts. To their eternal credit, the Miller brothers took this aspect of the design very seriously, giving their puzzles far more thought than Sierra at least tended to do. They went into Myst with no experience designing puzzles, and their insecurity about this aspect of their craft was perhaps their ironic saving grace. Before they even had a computer game to show people, they spent hours walking outsiders through their scenario Dungeons & Dragons-style, telling them what they saw and listening to how they tried to progress. And once they did have a working world on the computer, they spent more hours sitting behind players, watching what they did. Robyn Miller, asked in an interview shortly after the game’s release whether there was anything he “hated,” summed up thusly their commitment to consistent, logical puzzle design and world-building (in Myst, the two are largely one and the same):

Seriously, we hate stuff without integrity. Supposed “art” that lacks attention to detail. That bothers me a lot. Done by people who are forced into doing it or who are doing it for formula reasons and monetary reasons. It’s great to see something that has integrity. It makes you feel good. The opposite of that is something I dislike.

We tried to create something — a fantastic world — in a very realistic way. Creating a fantasy world in an unrealistic way is the worst type of fantasy. In Jurassic Park, the idea of dinosaurs coming to life in the twentieth century is great. But it works in that movie because they also made it believable. That’s how the idea and the execution of that idea mix to create a truly great experience.

Taken as a whole, Myst is a master class in designing around constraints. Plenty of games have been ruined by designers whose reach exceeded their core technology’s grasp. We can see this phenomenon as far back as the time of Scott Adams: his earliest text adventures were compact marvels, but quickly spiraled into insoluble incoherence when he started pushing beyond what his simplistic parsers and world models could realistically present. Myst, then, is an artwork of the possible. Managing inventory, with the need for a separate inventory screen and all the complexities of coding this portable object interacting on that other thing in the world, would have stretched HyperCard past the breaking point. So, it’s gone. Interactive conversations would have been similarly prohibitive with the technology at the Millers’ fingertips. So, they devised a clever dodge, showing the few characters that exist only as recordings, or through one-way screens where you can see them, but they can’t see (or hear) you; that way, a single QuickTime video clip is enough to do the trick. In paring things back so dramatically, the Millers wound up with an adventure game unlike any that had been seen before. Their problems really did become their game’s features.

For the most part, anyway. The networks of nodes and pre-rendered static views that constitute the worlds of Myst can be needlessly frustrating to navigate, thanks to the way that the views prioritize aesthetics over consistency; rotating your view in place sometimes turns you 90 degrees, sometimes 180 degrees, sometimes somewhere in between, according to what the designers believed would provide the most striking image. Orienting yourself and moving about the landscape can thus be a confusing process. One might complain as well that it’s a slow one, what with all the empty nodes which you must move through to get pretty much anywhere — often just to see if something you’ve done on one side of the map has had any effect on something on its other side. Again, a comparison with the twisty little passages of an old-school text adventure, filled with mostly empty rooms, does strike me as thoroughly apt.

On the other hand, a certain glaciality of pacing seems part and parcel of what Myst fundamentally is. This is not a game for the impatient. It’s rather targeted at two broad types of player: the aesthete, who will be content just to wander the landscape taking in the views, perhaps turning to a walkthrough to be able to see all of the worlds; and the dedicated puzzle solver, willing to pull out paper and pencil and really dig into the task of understanding how all this strange machinery hangs together. Both groups have expressed their love for Myst over the years, albeit in terms which could almost convince you they’re talking about two entirely separate games.

So much for Myst the artifact. What of Myst the cultural phenomenon?

The origins of the latter can be traced to the Miller brothers’ wise decision to take their game to Brøderbund. Brøderbund tended to publish fewer products per year than their peers at Electronic Arts, Sierra, or the lost and unlamented Mediagenic, but they were masterful curators, with a talent for spotting software which ordinary Americans might want to buy and then packaging and marketing it perfectly to reach them. (Their insistence on focus testing, so confusing to the Millers, is proof of their competence; it’s hard to imagine any other publisher of the time even thinking of such a thing.) Brøderbund published a string of products over the course of a decade or more which became more than just hits; they became cultural icons of their time, getting significant attention in the mainstream press in addition to the computer magazines: The Print Shop, Carmen Sandiego, Lode Runner, Prince of Persia, SimCity. And now Myst was about to become the capstone to a rather extraordinary decade, their most successful and iconic release of all.

Brøderbund first published the game on the Macintosh in September of 1993, where it was greeted with rave reviews. Not a lot of games originated on the Mac at all, so a new and compelling one was always a big event. Mac users tended to conceive of themselves as the sophisticates of the computer world, wearing their minority status as a badge of pride. Myst hit the mark beautifully here; it was the Mac-iest of Mac games. MacWorld magazine’s review is a rather hilarious example of a homer call. “It’s been polished until it shines,” wrote the magazine. Then, in the next paragraph: “We did encounter a couple of glitches and frozen screens.” Oh, well.

Helped along by press like this, Myst came out of the gates strong. By one report, it sold 200,000 copies on the Macintosh alone in its first six months. If correct or even close to correct, those numbers are extraordinary; they’re the numbers of a hit even on the gaming Mecca that was the Wintel world, much less on the Mac, with its vastly smaller user base.

Still, Brøderbund knew that Myst‘s real opportunity lay with those selfsame plebeian Wintel machines which most Mac users, the Miller brothers included, disdained. Just as soon as Cyan delivered the Mac version, Brøderbund set up an internal team — larger than the Cyan team which had made the game in the first place — to do the port as quickly as possible. Importantly, Myst was ported not to bare MS-DOS, where almost all “hardcore” games still resided, but to Windows, where the new demographics which Brøderbund hoped to attract spent all of their time. Luckily, the game’s slideshow visuals were possible even under Windows’s sluggish graphics libraries, and Apple had recently ported their QuickTime video system to Microsoft’s platform. The Windows version of Myst shipped in March of 1994.

And now Brøderbund’s marketing got going in earnest, pushing the game as the one showcase product which every purchaser of a new multimedia PC simply had to have. At the time, most CD-ROM based games also shipped in a less impressive floppy-disk-based version, with the latter often still outselling the former. But Brøderbund and Cyan made the brave choice not to attempt a floppy-disk version at all. The gamble paid off beautifully, furthering the carefully cultivated aspirational quality which already clung to Myst, now billed as the game which simply couldn’t be done on floppy disk. Brøderbund’s lush advertisements had a refined, adult air about them which made them stand out from the dragons, spaceships, and scantily-clad babes that constituted the usual motifs of game advertising. As the crowning touch, Brøderbund devised a slick tagline: Myst was “the surrealistic adventure that will become your world.” The Miller brothers scoffed at this piece of marketing-speak — until they saw how Myst was flying off the shelves in the wake of it.

So, through a combination of lucky timing and precision marketing, Myst blew up huge. I say this not to diminish its merits as a puzzle-solving adventure game, which are substantial, but simply because I don’t believe those merits were terribly relevant to the vast majority of people who purchased it. A parallel can be drawn with Infocom’s game of Zork, which similarly surfed a techno-cultural wave a decade before Myst. It was on the scene just as home computers were first being promoted in the American media as the logical, more permanent successors to the videogame-console fad. For a time, Zork, with its ability to parse pseudo-natural-English sentences, was seen by computer salespeople as the best overall demonstration of what a computer could do; they therefore showed it to their customers as a matter of course. And so, when countless new computer systems went home with their new owners, there was also a copy of Zork in the bag. The result was Infocom’s best-selling game of all time, to the tune of almost 400,000 copies sold.

Myst now played the same role in a new home-computer boom. The difference was that, while the first boom had fizzled rather quickly when people realized of what limited practical utility those early machines actually were, this second boom would be a far more sustained affair. In fact, it would become the most sustained boom in the history of the consumer PC, stretching from approximately 1993 right through the balance of the decade, with every year breaking the sales records set by the previous one. The implications for Myst, which arrived just as the boom was beginning, were titanic. Even long after it ceased to be particularly cutting-edge, it continued to be regarded as an essential accessory for every PC, to be tossed into the bags carried home from computer stores by people who would never buy another game.

Myst had already established its status by the time the hype over the World Wide Web and Windows 95 really lit a fire under computer sales in 1995. It passed the 1 million copy mark in the spring of that year. By the same point, a quickie “strategy guide” published by Prima, ideal for the many players who just wanted to take in its sights without worrying about its puzzles, had passed an extraordinary 300,000 copies sold — thus making its co-authors, who’d spent all of three weeks working on it, the two luckiest walkthrough authors in history. Defying all of the games industry’s usual logic, which dictated that titles sold in big numbers for only a few months before fizzling out, Myst‘s sales just kept accelerating from there. It sold 850,000 copies in 1996 in the United States alone, then another 870,000 copies in 1997. Only in 1998 did it finally begin to flag, posting domestic sales of just 540,000 copies. Fortunately, the European market for multimedia PCs, which lagged a few years behind the American one, was now also burning bright, opening up whole new frontiers for Myst. Its total retail sales topped 6 million by 2000, at least 2 million of them outside of North America. Still more copies — it’s impossible to say how many — had shipped as pack-in bonuses with multimedia upgrade kits and the like. Meanwhile, under the terms of Sunsoft’s original agreement with Cyan, it was also ported by the former to the Sega Saturn, Atari Jaguar, 3DO, and CD-I living-room consoles. Myst was so successful that another publisher came out with an elaborate parody of it as a full-fledged computer game in its own right, under the indelible title of Pyst. Considering that it featured the popular sitcom star John Goodman, Pyst must have cost far more to make than the shoestring production it mocked.

As we look at the staggering scale of Myst‘s success, we can’t avoid returning to that vexing question of why it all should have come to be. Yes, Brøderbund’s marketing campaign was brilliant, but there must be more to it than that. Certainly we’re far from the first to wonder about it all. As early as December of 1994, Newsweek magazine noted that “in the gimmick-dominated world of computer games, Myst should be the equivalent of an art film, destined to gather critical acclaim and then dust on the shelves.” So why was it selling better than guaranteed crowd-pleasers with names like Star Wars on their boxes?

It’s not that it’s that difficult to pinpoint some of the other reasons why Myst should have been reasonably successful. It was a good-looking game that took full advantage of CD-ROM, at a time when many computer users — non-gamers almost as much as gamers — were eager for such things to demonstrate the power of their new multimedia wundermachines. And its distribution medium undoubtedly helped its sales in another way: in this time before CD burners became commonplace, it was immune to the piracy that many publishers claimed was costing them at least half their sales of floppy-disk-based games.

Likewise, a possible explanation for Myst‘s longevity after it was no longer so cutting-edge might be the specific technological and aesthetic choices made by the Miller brothers. Many other products of the first gush of the CD-ROM revolution came to look painfully, irredeemably tacky just a couple of years after they had dazzled, thanks to their reliance on grainy video clips of terrible actors chewing up green-screened scenery. While Myst did make some use of this type of “full-motion video,” it was much more restrained in this respect than many of its competitors. As a result, it aged much better. By the end of the 1990s, its graphics resolution and color count might have been a bit lower than those of the latest games, and it might not have been quite as stunning at first glance as it once had been, but it remained an elegant, visually-appealing experience on the whole.

Yet even these proximate causes don’t come close to providing a full explanation of why this art film in game form sold like a blockbuster. There are plenty of other games of equal or even greater overall merit to which they apply equally well, but none of them sold in excess of 6 million copies. Perhaps all we can do in the end is chalk it up to the inexplicable vagaries of chance. Computer sellers and buyers, it seems, needed a go-to game to show what was possible when CD-ROM was combined with decent graphics and sound cards. Myst was lucky enough to become that game. Although its puzzles were complex, simply taking in its scenery was disarmingly simple, making it perfect for the role. The perfect product at the perfect time, perfectly marketed.

In a sense, Myst the phenomenon didn’t do that other Myst — Myst the actual artifact, the game we can still play today — any favors at all. The latter seems destined always to be judged in relation to the former, and destined always to be found lacking. Demanding that what is in reality a well-designed, aesthetically pleasing game live up to the earth-shaking standards implied by Myst‘s sales numbers is unfair on the face of it; it wasn’t the fault of the Miller brothers, humble craftsmen with the right attitude toward their work, that said work wound up selling 6 million copies. Nevertheless, we feel compelled to judge it, at least to some extent, with the knowledge of its commercial and cultural significance firmly in mind. And in this context especially, some of its detractors’ claims do have a ring of truth.

Arguably the truthiest of all of them is the oft-repeated old saw that no other game was bought by so many people and yet really, seriously played by so few of its purchasers. While such a hyperbolic claim is impossible to truly verify, there is a considerable amount of circumstantial evidence pointing in exactly that direction. The exceptional sales of the strategy guide are perhaps a wash; they can be as easily ascribed to serious players wanting to really dig into the game as they can to casual purchasers just wanting to see all the pretty pictures on the CD-ROM. Other factors, however, are harder to dismiss. The fact is, Myst is hard by casual-game standards — so hard that Brøderbund included a blank pad of paper in the box for the purpose of keeping notes. If we believe that all or most of its buyers made serious use of that notepad, we have to ask where these millions of people interested in such a cerebral, austere, logical experience were before it materialized, and where they went thereafter. Even the Miller brothers themselves — hardly an unbiased jury — admit that by their best estimates no more than 50 percent of the people who bought Myst ever got beyond the starting island. Personally, I tend to suspect that the number is much lower than that.

Perhaps the most telling evidence for Myst as the game which everyone had but hardly anyone played is found in a comparison with one of its contemporaries: id Software’s Doom, the other decade-dominating blockbuster of 1993 (a game about which I’ll be writing much more in a future article). Doom indisputably was played, and played extensively. While it wasn’t quite the first running-around-and-shooting-things-from-a-first-person-perspective game, it did become so popular that games of its type were codified as a new genre unto themselves. The first-person shooters which followed Doom in the 1990s were among the most popular games of their era. Many of their titles are known to gamers today who weren’t yet born when they debuted: titles like Duke Nukem 3D, Quake, Half-Life, Unreal. Myst prompted just as many copycats, but these were markedly less popular and are markedly less remembered today: AMBER: Journeys Beyond, Zork Nemesis, Rama, Obsidian. Only Cyan’s own eventual sequel to Myst can be found among the decade’s bestsellers, and even it’s a definite case of diminishing commercial returns, despite being a rather brilliant game in its own right. In short, any game which sold as well as Myst, and which was seriously played by a proportionate number of people, ought to have left a bigger imprint on ludic culture than this one did.

But none of this should affect your decision about whether to play Myst today, assuming you haven’t yet gotten around to it. Stripped of all its weighty historical context, it’s a fine little adventure game if not an earth-shattering one, intriguing for anyone with the puzzle-solving gene, infuriating for anyone without it. You know what I mean… sort of a niche experience. One that just happened to sell 6 million copies.

(Sources: the books Myst: Prima’s Official Strategy Guide by Rick Barba and Rusel DeMaria, Myst & Riven: The World of the D’ni by Mark J.P. Wolf, and The Secret History of Mac Gaming by Richard Moss; Computer Gaming World of December 1993; MacWorld of March 1994; CD-ROM Today of Winter 1993. Online sources include “Two Histories of Myst” by John-Gabriel Adkins, Ars Technica‘s interview with Rand Miller, Robyn Miller’s postmortem of Myst at the 2013 Game Developers Conference, GameSpot‘s old piece on Myst as one of the “15 Most Influential Games of All Time,” and Greg Lindsay’s Salon column on Myst as a “dead end.” Michael Bywater’s colorful comments about Myst come from Peter Verdi’s now-defunct Magnetic Scrolls fan site, a dump of which Stefan Meier dug up for me from his hard drive several years ago. Thanks again, Stefan!

The “Masterpiece Edition” of Myst is available for purchase from GOG.com.)

Lee_Ars

February 21, 2020 at 6:04 pm

Excellent work as always, Jimmy!

As a timely FYI, we just (as in literally within the past hour) released our extended 2-hr interview with Rand Miller for anyone who wants to hear some more directly from the man himself about HyperCard, The Manhole, Cosmic Osmo, and Myst’s long development process. Rand was awesome to spend time with, and the long interview has all kinds of cool stuff in it that I couldn’t cram down into the original 20-minute video.

The extended interview is on youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5qxg0ykOcgM

Jimmy Maher

February 21, 2020 at 8:38 pm

Well, you should have posted that a bit earlier, my friend… ;)

Andrew Plotkin

February 21, 2020 at 6:15 pm

> Putting the pages together, along with a fifth page found on the central island, allows you to free the brother of your choice. This last-minute branch to an otherwise unmalleable story […]

Sheesh, no mention of the third ending? :) Or were you trying to avoid spoilers?

The bonus ending (universally considered the “real” end of the story) which requires some extra digging (and ignoring the brothers’ explicit guidance!) is a nice design decision. The fact that it’s an information puzzle is pretty interesting. (That is, if you’ve played before or are working from a walkthrough, you can skip 90% of the game and go straight to the good ending.)

Jimmy Maher

February 21, 2020 at 8:41 pm

I confess I had no idea it existed. I played Myst seriously for the first time only recently, and was quite proud of myself for solving the whole thing without hints, with the exception only of a couple of pixel hunts I needed help with. Now I’ll have to go find out what the secret ending is all about.

But if I had known about it, I probably wouldn’t have mentioned it. I already debated whether describing the collecting of the journal pieces was too spoilery.

Sniffnoy

February 22, 2020 at 2:53 am

I’m surprised that if you didn’t find the good ending you didn’t say anything about, wow, this game just lets you choose between two bad endings, huh? That’s a bold choice…

Honestly I think of those two endings less as endings and more as fail states — time to reload your save and try again! (I guess they’re the only ones in the game…)

Sniffnoy

February 22, 2020 at 2:56 am

Actually, now that I remember, there’s actually one more fail state in addition to those two. So, there’s actually three bad endings and one good one, if we count fail states as endings.

Jimmy Maher

February 22, 2020 at 10:04 am

Okay, now I understand the confusion. I did see the good ending, assuming you mean the one where you actually meet Atrus. My problem was that I was remembering it as one of two possibilities, when it was actually one of three. When Zarf mentioned a hidden ending, and especially when he said it could be found at the very beginning, I was imagining some deep, dark Easter egg. Ironically, the key element to the good ending is actually shown in one of the screenshots above. I didn’t find arriving at it to be any big stretch. It was pretty obvious that neither brother was an honest broker.

I generally play the games I write about months in advance, and sometimes my memory and my notes fail me. It’s a problem, but one I’m not quite sure how to fix, in that I don’t want to be rushing a game for a deadline. That tends to create a highly artificial experience where *just getting done* takes precedence over appreciation. I’d rather know I have lots of time, and can take my time. I guess the only solution is to take better notes. Sorry for the confusion!

I still don’t know what you mean by a *fourth* ending, however…

Joshua Barrett

February 22, 2020 at 12:48 pm

If you meet Atrus without collecting the final page first, you fail.

Jimmy Maher

February 22, 2020 at 3:42 pm

Ah, okay.

Sniffnoy

February 23, 2020 at 12:33 am

Yup — Atrus gets special dialogue for it too. :)

Todd Carson

February 22, 2020 at 4:51 am

> The bonus ending (universally considered the “real” end of the story) which requires some extra digging (and ignoring the brothers’ explicit guidance!)

And, the player’s decision on whether to do what Sirrus or Achenar says all the way to the end will be informed by what they see in the brothers’ rooms in the other Ages. This is why I thought it was a little unfair to say that Myst has no storytelling outside of the journals in the library. The brothers’ living quarters are environmental storytelling giving you a different view of their lives than what they tell you.

Jimmy Maher

February 22, 2020 at 10:16 am

You know, you’re right. I could have done with a bit more of it, but it is there. I nixed that complaint. Thanks!

Andrew Plotkin

February 21, 2020 at 6:27 pm

As for the overwhelming sales numbers… I think Myst manages to provide a satisfying play experience even when you’re just fumbling around. Just circling the island gives you a varied set of environments full of evocative music, images, and toys to play with. If you don’t solve a puzzle, it’s not an ostentatiously unfulfilled mission — it’s a machine that reacts when you push the buttons. Which is still fun for newcomers.

Maybe you could say that for a lot of adventure games. I guess I’m saying that, in its design naivete, Myst *doesn’t* foreshadow all the places/chapters/experiences you’re missing out on. So if you pick it up for an hour and “get stuck”, you still feel like you’ve come out ahead.

James Schend

February 21, 2020 at 6:36 pm

Liked the article. Just a small observation, but as a kid who made *lots* of HyperCard stacks in his day, while it might have been a creative choice to not have an inventory in Myst, it’s certainly possible for HyperCard stacks to have “global” scope variables which can be used to track inventory items– that’s probably exactly how they tracked the state of those steampunk machines in the game. Drawing the inventory on screen atop any arbitrary location would also have been quite easy, using a “background card” with hidden UI elements.

Jimmy Maher

February 21, 2020 at 8:47 pm

You could probably *do* it, but I don’t think it would scale very well. If you didn’t want the game to be stubbornly obtuse, you’d have to code lots and lots of unique failure states, which in HyperTalk would probably have to come down to long strings of conditional statements. Then you would have to figure out how to communicate what was happening, etc.

But point taken that the line between technical restriction and aesthetic choice is quite blurred with Myst, here and elsewhere.

James Schend

February 21, 2020 at 9:22 pm

The biggest obstacle I suppose would be having to render the scene with the object there and removed, and the “goal” scene with the object there and removed, then a stand-alone render of the object for the inventory area. Which is like… nothing today but on computers at the time it would have been a big rendering time and storage hit.

However they already had to render a screen of those steampunk machines in each possible state/pose so it’s not like they weren’t already doing that anyway. So I’m inclined to think it was a purposeful choice.

Joshua Barrett

February 21, 2020 at 7:44 pm

I’ve always liked Myst—albeit, not quite as much as Doom—So I really do wonder where the hatred comes from. Did people accidentally play 7th Guest instead? That would explain it…

Not that Myst is perfect. It’s just good. And of course, Riven is much, much better. I adore that game.

Jimmy Maher

February 21, 2020 at 8:48 pm

Yes, The 7th Guest is truly a game worth hating…

sjf

February 22, 2020 at 7:23 am

Now is Riven a game worth loving?

Well, I guess I already liked Myst a lot and Riven really is much better. All the animals adding life to the world. The even more fantastical worlds. It feels much bigger as well.

Joshua Barrett

February 22, 2020 at 1:04 pm

Riven is absolutely worth loving. The worldbuilding is excellent, the setting is rich, and it contains one of my favorite puzzles ever (for the record, it’s the numbers puzzle—if you’ve played Riven, you know the one).

Of course, the flipside to that is the Riven is blisteringly hard in a way that Myst just isn’t. While Myst isn’t easy by any stretch, you can more or less fumble through quite a bit of it (including the compass puzzle in the Stoneship Age, which is arguably the worst puzzle in the game), and once you read the books on the shelf and get the rotations for the tower the main island is pretty simple.

That’s just not the case with Riven. There are only two real puzzles, and both of them are absolutely brutal tests of knowledge that rely on you putting together a fairly comprehensive understanding of the entire world. Beating Riven unaided is a real accomplishment that I could not manage.

dsparil

February 22, 2020 at 1:55 pm

I managed to finish Myst without help, but I ended up breaking down and buying the guide for Riven. A friend managed to finish it with his dad and brother without any outside help, but it took them over a year. I still find it hard to believe that it’s even possible.

Taras

February 27, 2020 at 9:13 am

I feel like the hatred of Myst has really dissipated in recent years. When I first played Riven and fell in love with it (I had played Myst and some Myst-likes as a kid) Cyan was not in a great state, mostly putting out wonky mobile games and yet more Myst ports. I scoured the internet for Riven/Myst trivia, reviews, retrospectives, and while I found a lot of stuff by fans that was positive, I definitely ran into a lot of myst vitriol and (after I learned to avoid that) discussions of myst vitriol. In both cases this stuff mainly seemed to be written by people who were teens or adults when myst was first released.

Then Cyan found renewed success with their Obduction kickstarter, games like The Witness started being released, and I started noticing people my age and younger, who had been little kids when myst was released, talking about myst, and I was surprised and heartened by the total lack of the usual vitriol in these discussions. Most seemed to have some fondness for myst, ranging from hardcore fans to just people with nostalgic memories of a game their grandmas had played with them. Even the people who have never played it, didn’t care to play it, or had tried it but decided it wasn’t for them couldn’t seem to muster up the usual anger. To my generation myst seems to be a favorite game, a fond memory, or just a piece of pop culture, not something to get heated about.

I guess this sort of thing is pretty much inevitable with everything but the most inflammatory pieces of art and media– eventually the ideological and aesthetic arguments that were once so important seem to become irrelevant, and the context that was so present and personal for people becomes academic. I think finally Myst, the good, pleasant game, is settling into it’s natural role, divorced from the faded hype of the 90’s CD-ROM boom, and I’m glad. Now if only people would play Riven!

Jonathan B

February 23, 2020 at 8:01 pm

I think the Myst hatred is not unlike the Blair Witch hatred. Both Myst and Blair Witch had their charms and were novel in their way — the problem was more what they inspired: terrible games with minimal interactivity and pre-rendered graphics on one hand, and movies using nauseating hand-held camera footage on the other.

Kroc Camen

February 21, 2020 at 7:53 pm

I feel that an opportunity was missed in this paragraph:

> Doom indisputably was played, […], it did became so popular that games of its type were codified as a new genre unto themselves. The first-person shooters which followed Doom in the 1990s were among the most popular games of their era.

I would replace “first-person shooters” with “Doom-clones” so as to codify that point that Doom defined the genre for a while, at least.

Jimmy Maher

February 21, 2020 at 8:49 pm

It’s a little unkind to call them all “Doom clones.” Games like Half-Life actually built on the formula in important ways.

James Schend

February 21, 2020 at 9:25 pm

If you get into the FPS area, please give Marathon some badly-needed pop-culture boost. It did pretty much everything Half-Life did, but better, and 3 years earlier. But since it was released for Macintosh only, it’s still almost entirely unknown.

To give you an idea of how ahead-of-its-time Marathon was, it had in-game voice-over-IP… in 1994. That wasn’t seen again in AAA games until, what, Battlefield 3?

xxx

February 22, 2020 at 7:34 pm

Saying that the Marathon series did “everything that Half-Life did” is definitely overstating the case. HL was a much more immersive single-player experience than Marathon, which was still quite constrained by the limitations of a 2.5D engine; it was able to do environmental storytelling, have conversational NPCs, puzzles more complicated than “push the button,” etc.

But the Marathon games did have a remarkably deep story — arguably the first good story in a first-person shooter — and, along with System Shock, was one of the first games to understand that “oh shit, here’s a lot of demons” is less tense and less interesting than “it’s dark and quiet, and I can hear something in the distance.” And yeah, it does deserve to be a lot more widely known than it is. When the franchise is mentioned at all these days, it’s only in the context of “spiritual antecedent to the Halo games,” but at the time it was huge in the Mac world and had a large, rabidly enthusiastic fan base.

(Full disclosure: I am writing this post on a laptop whose hostname is “durandal”.)

Matthew Parsons

February 23, 2020 at 5:24 pm

I believe you miss understood the previous posters intent: “first person shooter” was not coined/widely dissiminated yet. The term “doom clone” was used in press for quite a while to refer to what we would now call an “FPS”.

stl

February 24, 2020 at 11:20 am

That is(pardon my native tongue, which is not french) BS. Early 90ies was era of acronym usage and they spread like wildfire because of gamer usage. Akkkkktuallly – these terms were already established long before Doom came out, but Doom came into era, when PC gaming became commonly available(unlike ZX Spectrum, Amiga or others) and players came together to play LAN games – in other words: Doom. In 90ies there were plenty of FPS before Doom, there were even 3rd person shooters, like Tomb Raider, there were many RPG games, but “doom clones” specifically meant multiplayer and deathmatch modes in FPS games. Not to mention, that Doom was perceived as a clone of Wolfenstein 3D, which however was single player FPS. I don’t remember that much of the press influence for coining those acronyms – it might be true, that initially those acronyms were popularized by gaming magazines, but most of the gamers probably had no access to those, as they already had spent all their money in acquiring PC and not much was left over, so even Doom was pirated on empty floppy disks.

Jimmy Maher

February 26, 2020 at 1:49 pm

Fair enough, but the “FPS” acronym was already in use by the time of at least three of the four games I list as popular examples. From the modern reader’s perspective, using the term “Doom clone” there would inevitably come across as a deprecation.

Ross

February 26, 2020 at 10:55 pm

I always find it very strange that the history of gaming seems to treat Doom as the beginning of the FPS. It seems right in retrospect, but having lived through it, at the time, it really felt like Wolfenstein 3D was the seminal game in the genre, and Doom was more of “The next big step” – something that, while refining the genre considerably and importantly, was still very much following in the footsteps of what had come before. The extent to which Wolfenstein has become something of a footnote feels almost like if the history of platformers was presented as “Sonic the Hedgehog and its imitators”

Jimmy Maher

February 27, 2020 at 12:20 pm

I understand what you’re saying, but I don’t really believe that the weight given to Doom in most gaming histories is misbegotten. Just as with Myst, it’s a question Doom the artifact versus Doom the cultural phenomenon. While the former is indeed a fairly logical expansion upon Wolfenstein 3D, the latter changed the direction of an entire industry when it became not just successful but *astoundingly* so.

More to come on that topic in the near future…

Lt. Nitpicker

February 21, 2020 at 10:15 pm

The overlap between Doom and Myst players is more likely than you think when you consider how much the latter levels of Doom and Doom II focus on combat encounters almost structured like puzzles, where you need to use your movement options (even sometimes the level environment itself, like dodging an archvile’s line of sight attack) and weapons, combined with threat prioritization, to survive. Also, I see one instance of “Miller brother” where the plural would be more appropriate.

Jimmy Maher

February 21, 2020 at 10:18 pm

Thanks!

stl

February 24, 2020 at 11:40 am

Even if Myst was older game, it became known to wider public about year after Doom – along with some other gems. That might be a reason why it was not perceived well, as it was already outdated game. Lost Eden was my first walking simulator and… you can see why I might have been baffled why Myst gets so much of attention.

I do remember there was some hype(rather artificial) about Myst in those olden days, but the nature of that ‘hype’ was mostly small talk, where players were asking each other about some new games that they were not playing and that they discovered and sometimes Myst was mentioned… there were some questions what was so special about that game and then they went back to Doom, HOMM, Civilization or whatever else was there.

This small talk is the only reason why I was drawn to this article, as there is some mystery for most of the gamers about Myst, unless they sat down and start to play it… and run away. :)

hatless

February 26, 2020 at 1:09 pm

I offer the hot take that Doom and Myst are very nearly the same game! I just got round to playing Obduction (the modern spiritual sequel to Myst) last week, and the satisfaction of exploring a complex environment, building a mental map of the world and unlocking doors and activating lifts was identical to the satisfaction of doing those same things in a fanmade Doom map.

(But Doom also tests your survival skills — is Myst just Doom dumbed down for the masses? ;))

Keith Palmer

February 21, 2020 at 11:13 pm

Myst “clicked” with me from pretty much the moment my brother brought a borrowed CD-ROM home around 1994 or so (there being at least a few other Macintosh users in our area), and I’ve tried to articulate some reasons why beyond “you had to be there” shrugs about the graphics not looking like anything else at the time and that ultimate brushoff “so starved for games I can’t tell what a good one looks like.”

I see the point of you bringing up “aesthetes and puzzle solvers,” and yet while before getting to Myst I’d bumped up against several walls in “The Lost Treasures of Infocom” to the point of downplaying my puzzle-solving skills to this day, with Myst I’d got off Myst Island to some of the Ages before we had to return that first CD, and when we had our own copy I took notes (our box had not just a “notepad” but a notebook, which I still have) and sorted through each mechanism in turn with a sense of satisfaction, only having real problems with the compass rose in the Stoneship Age.

Perhaps what really helped me was being able to contrast the descriptions in the library of inhabited Ages with the abandoned ones implemented, thinking something ominous had happened and standing in judgment. Maybe I supposed myself “completing the story” (in the remaining pages of the notebook after I’d steered to the ending Andrew Plotkin alluded to earlier, I wrote down a simple idea for the backstory, which might not have altogether helped me reading the spinoff novels.) Anyway, Myst is not the only property apparently intended to have wide appeal, but which attracts plenty of criticism online, that I still feel fonder than many for…

Jacen aka Jaina

February 22, 2020 at 12:56 am

Miller brothers, humble craftsman with the right” craftsmen?

Andy

February 22, 2020 at 1:35 am

I enjoyed the article, but I must say, the claim that Myst didn’t leave a very big imprint on ludic culture seems very odd to me. I thought Myst is widely considered to have been incredibly influential! Just because there’s no one standout megahit among its first few years of copycats doesn’t mean that they weren’t an important phenomenon that spawned a broad and lasting family tree.

What about all of the myriad games of the past 25 years designed around cryptic passcodes to find and cryptic mechanisms to manipulate? What about any game of careful observation in a rich 3D environment? More specifically, what about the teeming sea of room escape games, which are really just pared-down Myst-likes? (And then what about real-world escape rooms?)

Or what about the Myst’s distinctive aesthetic blend of fantastical, lonely, surrealist serenity? Hasn’t it gone one to become one of the basic settings for games, up there with Tolkien and “Alien”? Modern puzzle games like The Witness and The Talos Principle are able to do direct homage to Myst in their environmental design while simultaneously just being intuitive and appealing on present-day terms. Isn’t that the opposite of a “niche experience”?

And then on a slightly different branch of the tree of influence: what about the whole market for quiet, slow-paced, invitingly atmospheric “casual” games marketed to people other than young men, like hidden-object games, or the Nancy Drew series, et al.? And then by extension, what about everything else in the casual / mobile phone market? Isn’t all of that in some sense the real legacy of Myst?

Your answer may well be, “no, it’s really not,” but I’d want to read your reasons why not in more depth. I thought these notions of its influence were widespread.

(Also, possible copy edit: you take a moment to note that the game chooses to call its different areas “worlds,” but that would in fact be a pretty normal and self-explanatory thing for it to do; didn’t you mean to say that it calls them “ages”?)

Jimmy Maher

February 22, 2020 at 9:37 am

Good catch on the “ages.” Thanks!

I find some parts of what you’ve written more compelling than other parts. I think it’s a stretch to attribute the whole casual-game market in any marked degree to Myst. Its most obvious antecedent is Tetris — also the first really popular mobile game outside the traditional gaming demographic, and a game that was, unlike Myst, obsessively *played* by just about everyone who encountered it. As I noted in the article, Myst’s design values are largely opposed to casual design values: Myst is *hard*, lacks difficulty levels, is absolutely committed to its aesthetic even when it comes at the price of player convenience, etc. We can certainly say that many of the same demographics who would later become casual players bought Myst, but any direct line of influence from the one to the other strikes me as tenuous at best. I’ve never seen any of the pioneers in the casual-game space refer to Myst as a major influence. Similarly, for his book A Casual Revolution, Jesper Juul interviewed a lot of casual players (many of whom devoted as much time to playing as hardcore players, but such is the nature of genre and taxonomy in the ludic space). Tetris is the name that comes up again and again among them when asked about their gateway game. Myst isn’t mentioned at all.

I would say much the same about the Nancy Drew games. Those games are heavily plot- and character-focused, with fixed storytelling arcs — almost anti-Mysts. I see a vastly stronger influence from traditional graphic adventures there, with the frustrations and overly taxing puzzles removed, difficulty levels implemented, etc., to suit a more casual market.

The fact is that The Witness and Talos Principle *are* niche games. They may sell more than even many hits from the era of Myst, thanks to the vastly expanded market for games in general today, but compared to a big AAA game, or for that matter a hit mobile casual game, they’re nowhere. ;)

Semantic quibbles aside, though, the question of Myst as an influence on modern games is an interesting one. I must confess that playing The Talos Principle doesn’t really put me in mind of Myst; just having the artificial intelligence talking to me constantly gives it a very different atmosphere. (More like Journeyman Project 2, maybe?) And its puzzles are all of a piece, a classic example of building upon a single mechanic to make the player feel like a genius by the end. Myst’s puzzles are very different, being much more in the mold of traditional adventure games. The undeniable influence on Talos Principle is Portal (the more recent one). Can we draw a line from Portal back to Myst? That, again, does strike me as a bit of a stretch. I certainly wouldn’t use the word “homage.”

When we come to the question of Myst as a more subtle aesthetic influence, you’re on firmer ground. Of course, Myst wasn’t the first to create this kind of atmosphere of lonely desolation: read the description of Flood Control Dam #3 in Zork I, a passage bound to strike many today as anachronistically “Myst-like.” Loneliness has always had a natural appeal to game designers because it saves them an awful lot of complications with implementing other characters.

Nor were mechanical puzzles with global effects on the environment original to Myst. Again, we see a fair amount of them in Infocom, in places like Zork III and Spellbreaker.

Still, I’m willing to accept that Myst was some influence here on those designers who came later. And you’re right that the genre of room-escape games do owe a definite debt to Myst.

My claim was never that Myst left no imprint on gaming. It’s just that Doom’s was vastly more obvious, vastly more direct, and vastly more commercially successful. The difference here is that Doom spawned a string of workalikes which were almost as successful as it was, several of them being among the top ten games of the 1990s. Myst spawned a similar string… for a while, until it became clear that there was no mass market yearning for more games in this style. It’s valid, I think, to ask why Doom’s long-term influence was so direct and concrete while Myst’s was, at best, more attenuated, when both games appear to have sold roughly the same number of copies.

Thanks for pushing back and causing me to think more deeply about these things!

gamerindreams

February 22, 2020 at 1:13 pm

I would say the whole walking simulators genre like Gone Home, Dear Esther, Vanishing of Ethan Carter, Firewatch also show a Myst influence and they are growing in numbers daily

These games have the same feel of walking around a beautifully rendered (in real time) space all alone solving puzzles (although for the most part they are much easier than Myst puzzles) that trigger audio/video memories

Even Murdered Soul Suspect – when you enable the cheat to ignore ghosts becomes a very contemplative detective game – walking around saving people’s souls

Petter Sjölund

February 22, 2020 at 2:38 pm

While I agree that many walking simulators are reminiscent of Myst, I think this is more of an accident than a direct influence. It just so happens that if you take a first-person shooter and remove an element that many people find off-putting, the shooting, you end up in pretty much the same place as you would if you took a Myst clone and removed the puzzles. The “trigger memories” thing does not happen in any Myst games as far as I remember, while it is a staple in horror-themed shooters.

Richard Wells

February 24, 2020 at 5:16 am

I am not sure it is that different. The triggered memories give the player knowledge of the character the player operates backstory while the finding of a page in Myst provides the player with part of the brothers’ backstories. I have played games where a room had a puzzle where items needed to be moved and adjusted to find the clues to be able to get to the next set of rooms with the next set of clues all covered with a spooky music track. Effectively, it was Myst reskinned to the real world but made more affordable by not having any other characters.

Andy

February 22, 2020 at 5:34 pm

Thanks for the detailed response!

Regarding Myst’s possible influence on the “casual” market, I was just referring to the way the industry conceives of what players want from games. I had always thought Myst was considered significant for introducing the idea that a broader demographic — specifically one that included female players and older players — might show up for games that were “pretty” and “relaxing,” games that had a enveloping and dreamy quality, and that might scratch the same itch as sitting somewhere cozy and piecing together a jigsaw puzzle. Maybe hard to exactly quantify what that thread is but I do think there’s one there.

And I didn’t mean to be saying that Talos Principle is a Myst-like; in terms of gameplay it is, as you say, a Portal-like, which I agree is quite a different thing. I just meant that Talos Principle, like many modern games, has a certain flavor of dreamlike serene environment that follows closely in Myst’s footsteps — islands in endless seas, surreal juxtapositions of abandoned architecture and mysterious technologies. And also a thematic overlap with Myst in terms of the meaning of that kind of landscape: Myst is all about the creation of virtual worlds by writing them, seemingly a metaphor for the game design process itself and our relationship to computers generally. And sure enough both The Talos Principle and The Witness justify their Myst-y landscapes as: virtual worlds, with a slightly melancholy implication. The underlying theme of lonely escape into the surreal beauty of the virtual is, as you say, traceable back to Zork and beyond, but Myst gave it a look and feel that has stuck around.

As for whether such games are “niche” or not, yes, it’s all relative, and you’re certainly right that we don’t live in a world where any of this sort of stuff dominates the culture at large. I guess it’s just hard for me to even conceive of an alternative history, in which slow quiet games are just as popular as fast noisy ones. As if! In movies, all other genres are niche compared to superhero movies, but that’s not their fault!

I guess I’m saying that I take Doom’s dominance and Myst’s relative niche-iness as having been natural and inevitable, reflecting societal predilections that go way beyond games, and thus not even requiring comment, but you’re right that it’s interesting to investigate that assumption more closely. I look forward to reading your take on the subsequent history as it unspools!

calvin

February 22, 2020 at 2:42 pm

How a “walking simulators” (like The Witness as you mention, Firewatch, or Gone Home) plays and how “core” gamers spoke against them reminds me a lot of the Myst drama of the time, FWIW.

xxx

February 22, 2020 at 7:40 pm

Too true. If there’s one thing gamers can’t seem to resist, then and now, it’s a “No True Scotsman” argument!

That said, it was heartening to see a funny counterexample to that sort of intolerance recently: https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/2020/02/20/the-doom-and-animal-crossing-fandoms-wish-each-other-luck-are-wholesome-and-lovely/

Avian Overlord

February 22, 2020 at 11:27 pm

It’s something of an inversion though. Myst was controversial because it cast story aside (well, more or less), to focus on mechanical puzzles and world exploration, whereas walking simulators are controversial for for casting aside mechanical challenge entirely in favor of story.

Brian Bagnall

April 28, 2020 at 12:32 pm

Good comments. One other popular game series that owes a debt to Myst is the series The Room (nothing to do with Tommy Wiseau). They’re almost more Myst than Myst, because of the complexity of the mechanical devices. Also, these type of games are great in VR where you just want to explore an interesting environment but also have something to do. The latest game in the series is The Room: a Dark Matter, which is VR exclusive and is terrific.

Derek

February 22, 2020 at 3:22 am

Now we’re getting into the gaming era I remember—but even in the 1990s I was behind the times. Jimmy has made this point before, but it bears repeating: computers were changing so fast and becoming obsolete so rapidly in the 1990s that a lot of people were unable to play recent games. I was a child then, and a CD-ROM drive wasn’t high on my parents’ list of priorities, so until we got one in 1997 all the games I played were either professionally released products from the era just before CDs became standard (including SimCity, Prince of Persia, and Spelunx) or shareware. As soon as we got a drive, a family friend loaned us Myst, and solving the game became something of a family project. (I remain proud of figuring out how to reach the Stoneship Age.)

So I missed the hoopla surrounding Myst and got into adventure games just before the adventure game market started to die off. Ours can’t have been the only family that was behind the times that way.

Also, I’ll take this opportunity to plug Ivy Allie’s series of essays, Myst in Retrospect: http://ivyallie.com/myst/. The review of Myst itself is a bit thin, and I’m not sure how familiar Allie is with the prior history of adventure games, but the essays on the sequels are excellent, and if I don’t recommend them here I’ll have to wait around until Riven shows up at the Digital Antiquarian, which will be a looong time.

Owen C.

February 22, 2020 at 4:20 am

Excellent article as usual, though I was a little bit miffed to see The Journeyman Project lumped into the category of “Myst copycats” when it was actually released several months before Myst (January 1993 compared to Myst’s September 1993 release.) I guess the confusion stems from the game getting a later “Turbo” re-release that was optimized for faster loading times.

Jimmy Maher

February 22, 2020 at 10:13 am

Good catch! Fortunately, there’s a lot other titles to choose from. ;)

Not Fenimore

February 22, 2020 at 1:14 pm

Journeyman Project 3 was the first game I ever beat end to end! Well, “beat”. I suspect I leaned on Arthur a lot for hints, but they did it organically enough I didnt mind.

Ross

February 23, 2020 at 3:55 pm

Journeyman 3 was my favorite game straight through to Gone Home, but it’s a very different beast from the first one. The series as a whole really showcases the evolution of the genre (though it feels a few years behind the times at every beat). The first one is certainly the most myst-like, but it’s also representative of the classic age of adventure games in several ways, with its scoring mechanism, frequent cheap deaths, learn-by-death and mechanics that discourage exploration. The second one drops the scoring mechanism and encourages exploration and nonlinear gameplay, retains deaths but avoids dead-man-walking. It also replaces the hypercard-style slideshow presentation with a more sophisticated 2.5d interface. The third game pushes the UI elements all the way out to the edges, adds NPCs, removes death altogether, adds puzzles based on global narrative state, and changes from discreet camera angles to free-scrolling 360 panoramic nodes.

Then you get to the real weird fact that there are six games journeyman project games, and three of them are the first one.

Todd Carson

February 22, 2020 at 4:54 am

The article says that the team consisted only of the Millers plus Chuck Carter and Chris Brandkamp, but there was at least one other well-known member: programmer Richard A. Watson, a.k.a. RAWA, who went on to create the D’ni language and numeral system that would feature in the subsequent games. He can be seen playing Prince of Persia in the “making of” video that originally shipped with Myst.

Jimmy Maher

February 22, 2020 at 10:20 am

Thanks! Missed his credit in the manual somehow.

Pedro Timóteo

February 22, 2020 at 8:30 am

But, however they categorize it, they’re happy to credit it with all but killing the adventure genre dead by the end of the 1990s. Myst, so this narrative goes, prompted dozens of studios to abandon storytelling and characters in favor of yet more sterile, hermetically sealed worlds just like its. And when the people understandably rejected this airless vision, that was that for the adventure game writ large.

I was expecting you to come back to this, but you didn’t. :) So, do those accusations have merit? They’re not a reason to “hate” Myst, much less the authors, of course, but I kind of feel that Myst *did* harm adventure games, not only for the reason you mentioned above, but also because it might have made companies consider other adventure games “failures” because they didn’t sell six million copies, and stop financing the genre altogether…

Jimmy Maher

February 22, 2020 at 10:33 am

The full answer will come more organically, as we see what followed Myst. ;)

But my short answer would be that, yes, there is some partial merit to such claims. Myst undoubtedly created a bubble, as half the industry concluded that they could get rich by making their own 3D-modelled slideshow adventure game. (The other half, one might say, was suddenly making Doom clones, with considerably more commercial success.) But few others had the talent of the Miller brothers, and many or most were in it for the manifestly wrong reasons, with the result that all of the unfair complaints that are typically levied at Myst — incomprehensible puzzles, etc. — apply more accurately to its many clones. (It’s notable that there are no slider puzzles in Myst…) And when the vast majority of the Myst clones flopped in a saturated market, it was all too easy for the industry to conclude that the problem was adventure games in general, not this specific implementation of them.

On the other hand, this is by no means *all* that brought the genre down. Terrible puzzle design, alas, wasn’t limited to Myst clones. This, I think, was the broader reason that so many people concluded that adventure games in general just weren’t much fun. Throw in a changing industry with changing player demographics, preferring games with more immediate and visceral thrills, and what happened seems fairly inevitable.

Besides, some Myst clones were genuinely good games…

Derek

February 22, 2020 at 3:17 pm

Myst clones are the one area of gaming history I know reasonably well, so I’ll be interested to see which of them you consider worth writing articles about. Some of them were interestingly weird, but I don’t know if you’d count any of the weird ones among the good ones.

A niggle: “…the old ‘nameless, faceless adventurer’ paragon…” Do you mean “paradigm”?

Jimmy Maher

February 22, 2020 at 3:59 pm

Yeah, that’s the word I was looking for. Thanks!

If you’d care to tell me which ones you think are worth looking at, it might be helpful…

Andrew Plotkin

February 23, 2020 at 6:42 pm

It’s hard to make recommendations in the post-Myst adventure bubble. Not because the games are all bad! But because they’re all kind of like Myst: good in some areas, weak in others. Ground out without a lot of game-design experience, at least not in the adventure game genre.

I played a bunch of them because I was hungry for first-person immersion and was willing to take the bad with the good.

Riven was certainly the standout of the late 90s. Cyan thought hard about design principles, put in all the storyline that Myst was missing, and hit all the marks.

But you could also feel good about playing Lighthouse (creepy), Obsidian (early, but very surreal), the whole Journeyman Project series, The Dark Eye (Poe adaptation), Morpheus (interesting story idea), Zork Nemesis (impressively arcane atmosphere, albeit barely connected to Zork), Dark Fall (start of an ongoing indie horror series), Rhem (Myst if it were designed by an absolute puzzle fiend who cared even less about story than Myst did), Alida (Myst if it were built on a giant guitar).

There was also a steady stream of European imports published by Dreamcatcher, which were minor but reliably decent if you just wanted to play another one of that sort of thing.

On the down side, there were some high-profile, highly hyped titles which turned out to be washouts when you tried to play them. Schizm and Starship Titanic, for obvious examples.