Microsoft, intent on its mission to destroy Netscape, rolled out across the industry with all the subtlety and attendant goodwill of Germany invading Poland…

— Merrill R. Chapman

No one reacted more excitedly to the talk of Java as the dawn of a whole new way of computing than did the folks at Netscape. Marc Andreessen, whose head had swollen exactly as much as the average 24-year-old’s would upon being repeatedly called a great engineer, businessman, and social visionary all rolled into one, was soon proclaiming Netscape Navigator to be far more than just a Web browser: it was general-purpose computing’s next standard platform, possibly the last one it would ever need. Java, he said, generously sharing the credit for this development, was “as revolutionary as the Web itself.” As for Microsoft Windows, it was merely “a poorly debugged set of device drivers.” Many even inside Netscape wondered whether he was wise to poke the bear from Redmond so, but he was every inch a young man feeling his oats.

Just two weeks before the release of Windows 95, the United States Justice Department had ended a lengthy antitrust investigation of Microsoft’s business practices with a decision not to bring any charges. Bill Gates and his colleague took this to mean it was open season on Netscape.

Thus, just a few weeks after the bravura Windows 95 launch, a war that would dominate the business and computing press for the next three years began. The opening salvo from Microsoft came in a weirdly innocuous package: something called the “Windows Plus Pack,” which consisted mostly of slightly frivolous odds and ends that hadn’t made it into the main Windows 95 distribution — desktop themes, screensavers, sound effects, etc. But it also included the very first release of Microsoft’s own Internet Explorer browser, the fruit of the deal with Spyglass. After you put the Plus! CD into the drive and let the package install itself, it was as hard to get rid of Internet Explorer as it was a virus. For unlike all other applications, there appeared no handy “uninstall” option for Internet Explorer. Once it had its hooks in your computer, it wasn’t letting go for anything. And its preeminent mission in life there seemed to be to run roughshod over Netscape Navigator. It inserted itself in place of its arch-enemy in your file associations and everywhere else, so that it kept turning up like a bad penny every time you clicked a link. If you insisted on bringing up Netscape Navigator in its stead, you were greeted with the pointed “suggestion” that Internet Explorer was the better, more stable option.

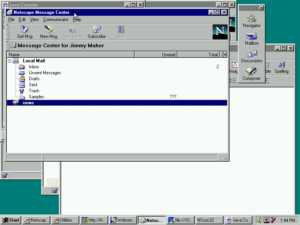

Microsoft’s biggest problem at this juncture was that that assertion didn’t hold water; Internet Explorer 1.0 was only a modest improvement over the old NCSA Mosaic browser on whose code it was based. Meanwhile Netscape was pushing aggressively forward with its vision of the browser as a platform, a home for active content of all descriptions. Netscape Navigator 2.0, whose first beta release appeared almost simultaneously with Internet Explorer 1.0, doubled down on that vision by including an email and Usenet client. More importantly, it supported not only Java but a second programming language for creating active content on the Web — a language that would prove much more important to the evolution of the Web in the long run.

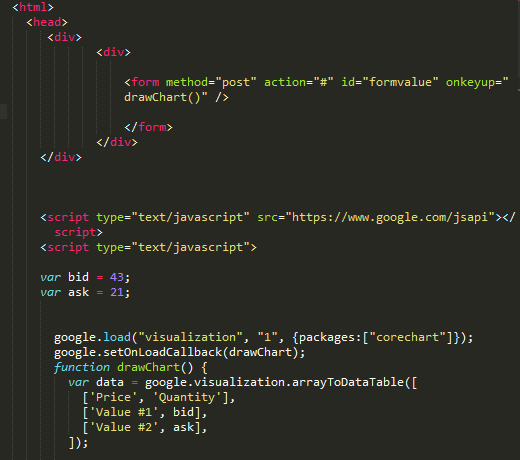

Even at this early stage — still four months before Sun would deign to grant Java its own 1.0 release — some of the issues with using it on the Web were becoming clear: namely, the weight of the virtual machine that had to be loaded and started before a Java applet could run, and said applet’s inability to communicate easily with the webpage that had spawned it. Netscape therefore decided to create something that lay between the static simplicity of vanilla HTML and the dynamic complexity of Java. The language called JavaScript would share much of its big brother’s syntax, but it would be interpreted rather than compiled, and would live in the same environment as the HTML that made up a webpage rather than in a sandbox of its own. In fact, it would be able to manipulate that HTML directly and effortlessly, changing the page’s appearance on the fly in response to the user’s actions. The idea was that programmers would use JavaScript for very simple forms of active content — like, say, a popup photo gallery or a scrolling stock ticker — and use Java for full-fledged in-browser software applications — i.e., your word processors and the like.

In contrast to Java, a compiled language walled off inside its own virtual machine, JavaScript is embedded directly into the HTML that makes up a webpage, using the handy “<script>” tag.

There’s really no way to say this kindly: JavaScript was (and is) a pretty horrible programming language by any objective standard. Unlike Java, which was the product of years of thought, discussion, and experimentation, JavaScript was the very definition of “quick and dirty” in a computer-science context. Even its principal architect Brendan Eich doesn’t speak of it like an especially proud parent; he calls it “Java’s dumb little brother” and “a rush job.” Which it most certainly was: he designed and implemented JavaScript from scratch in a matter of bare weeks.

What he ended up with would revolutionize the Web not because it was good, but because it was good enough, filling a craving that turned out to be much more pressing and much more satisfiable in the here and now than the likes of in-browser word processing. The lightweight JavaScript could be used to bring the Web alive, to make it a responsive and interactive place, more quickly and organically than the heavyweight Java. Once JavaScript had reached a critical mass in that role, it just kept on rolling with all the relentlessness of a Microsoft operating system. Today an astonishing 98 percent of all webpages contain at least a little bit of JavaScript in addition to HTML, and a cottage industry has sprung up to modify and extend the language — and attempt to fix the many infelicities that haunt the sleep of computer-science professors all over the world. JavaScript has become, in other words, the modern world’s nearest equivalent to what BASIC was in the 1980s, a language whose ease of use, accessibility, and populist appeal make up for what it lacks in elegance. These days we even do online word processing in JavaScript. If you had told Brendan Eich that that would someday be the case back in 1995, he would have laughed as loud and long at you as anyone.

Although no one could know it at the time, JavaScript also represents the last major building block to the modern Web for which Marc Andreessen can take a substantial share of the credit, following on from the “image” tag for displaying inline graphics, the secure sockets layer (SSL) for online encryption (an essential for any form of e-commerce), and to a lesser extent the Java language. Microsoft, by contrast, was still very much playing catch-up.

Nevertheless, on December 7, 1995 — the symbolism of this anniversary of the United States’s entry into World War II was lost on no one — Bill Gates gave a major address to the Microsoft faithful and assembled press, in which he made it clear that Microsoft was in the browser war to win it. In addition to announcing that his company too would bite the bullet and license Java for Internet Explorer, he said that the latter browser would no longer be a Windows 95 exclusive, but would soon be made available for Windows 3 and even MacOS as well. And everywhere it appeared, it would continue to sport the very un-Microsoft price tag of free, proof that this old dog was learning some decidedly new tricks for achieving market penetration in this new era of online software distribution. “When we say the browser’s free, we’re saying something different from other people,” said Gates, in a barbed allusion to Netscape’s shareware distribution model. “We’re not saying, ‘You can use it for 90 days,’ or, ‘You can use it and then maybe next year we’ll charge you a bunch of money.'” Netscape, whose whole business revolved around its browser, couldn’t afford to give Navigator away, a fact of which Gates was only too well aware. (Some pundits couldn’t resist contrasting this stance with Gates’s famous 1976 “Open Letter To Hobbyists,” in which he had asked, “Who can afford to do professional work for nothing?” Obviously Microsoft now could…)

Netscape’s stock price dropped by $28.75 that day. For Microsoft’s research budget alone was five times the size of Netscape’s total annual revenues, while the bigger company now had more than 800 people — twice Netscape’s total headcount — working on Internet Explorer alone. Marc Andreessen could offer only vague Silicon Valley aphorisms when queried about these disparities: “In a fight between a bear and an alligator, what determines the victor is the terrain” — and Microsoft, he claimed, had now moved “onto our terrain.” The less abstractly philosophical Larry Ellison, head of the database giant Oracle and a man who had had more than his share of run-ins with Bill Gates in the past, joked darkly about the “four stages” of Microsoft stealing someone else’s innovation. Stage 1: to “ridicule” it. Stage 2: to admit that, “yeah, there are a few interesting ideas here.” Stage 3: to make its own version. Stage 4: to make the world forget that the non-Microsoft version had ever existed.

Yet for the time being the Netscape tail continued to wag the Microsoft dog. A more interactive and participatory vision of the Web, enabled by the magic of JavaScript, was spreading like wildfire by the middle of 1996. You still needed Netscape Navigator to experience this first taste of what would eventually be labelled Web 2.0, a World Wide Web that blurred the lines between readers and writers, between content consumers and content creators. For if you visited one of these cutting-edge sites with Internet Explorer, it simply wouldn’t work. Despite all of Microsoft’s efforts, Netscape in June of 1996 could still boast of a browser market share of 85 percent. Marc Andreessen’s Sun Tzu-lite philosophy appeared to have some merit to it after all; his company was by all indications still winning the browser war handily. Even in its 2.0 incarnation, which had been released at about the same time as Gates’s Pearl Harbor speech, Internet Explorer remained something of a joke among Windows users, the annoying mother-in-law you could never seem to get rid of once she showed up.

But then, grizzled veterans like Larry Ellison had seen this movie before; they knew that it was far too early to count Microsoft out. That August, both Netscape and Microsoft released 3.0 versions of their browsers. Netscape’s was a solid evolution of what had come before, but contained no game changers like JavaScript. Microsoft’s, however, was a dramatic leap forward. In addition to Java support, it introduced JScript, a lightweight scripting language that just so happened to have the same syntax as JavaScript. At a stroke, all of those sites which hadn’t worked with earlier versions of Internet Explorer now displayed perfectly well in either browser.

With his browser itself more or less on a par with Netscape’s, Bill Gates decided it was time to roll out his not-so-secret weapon. In October of 1996, Microsoft began shipping Windows 95’s “Service Pack 2,” the second substantial revision of the operating system since its launch. Along with a host of other improvements, it included Internet Explorer. From now on, the browser would ship with every single copy of Windows 95 and be installed automatically as part of the operating system, whether the user wanted it or not. New Windows users would have to make an active choice and then an active effort to go to Netscape’s site — using Internet Explorer, naturally! — and download the “alternative” browser. Microsoft was counting on the majority of these users not knowing anything about the browser war and/or just not wanting to be bothered.

Microsoft employed a variety of carrots and sticks to pressure other companies throughout the computing ecosystem to give or at the bare minimum to recommend Internet Explorer to their customers in lieu of Netscape Navigator. It wasn’t above making the favorable Windows licensing deals it signed with big consumer-computer manufacturers like Compaq dependent on precisely this. But the most surprising pact by far was the one Microsoft made with America Online (AOL).

Relations between the face of the everyday computing desktop and the face of the Internet in the eyes of millions of ordinary Americans had been anything but cordial in recent years. Bill Gates had reportedly told Steve Case, his opposite number at AOL, that he would “bury” him with his own Microsoft Network (MSN). Meanwhile Case had complained long and loud about Microsoft’s bullying tactics to the press, to the point of mooting a comparison between Gates and Adolf Hitler on at least one occasion. Now, though, Gates was willing to eat crow and embrace AOL, even at the expense of his own MSN, if he could stick it to Netscape in the process.

For its part, AOL had come as far as it could with its Booklink browser. The Web was evolving too rapidly for the little development team it had inherited with that acquisition to keep up. Case grudgingly accepted that he needed to offer his customers one of the Big Two browsers. All of his natural inclinations bent toward Netscape. And indeed, he signed a deal with Netscape to make Navigator the browser that shipped with AOL’s turnkey software suite — or so Netscape believed. It turned out that Netscape’s lawyers had overlooked one crucial detail: they had never stipulated exclusivity in the contract. This oversight wasn’t lost on the interested bystander Microsoft, which swooped in immediately to take advantage of it. AOL soon announced another deal, to provide its customers with Internet Explorer as well. Even worse for Netscape, this deal promised Microsoft not only availability but priority: Internet Explorer would be AOL’s recommended, default browser, Netscape Navigator merely an alternative for iconoclastic techies (of which there were, needless to say, very few in AOL’s subscriber base).

What did AOL get in return for getting into bed with Adolf Hitler and “jilting Netscape at the altar,” as the company’s own lead negotiator would later put it? An offer that was impossible for a man with Steve Case’s ambitions to refuse, as it happened. Microsoft would put an AOL icon on the desktop of every new Windows 95 installation, where the hundreds of thousands of Americans who were buying a computer every month in order to check out this Internet thing would see it sitting there front and center, and know, thanks to AOL’s nonstop advertising blitz, that the wonders of the Web were just one click on it away. It was a stunning concession on Microsoft’s part, not least because it came at the direct cost of MSN, the very online network Bill Gates had originally conceived as his method of “burying” AOL. Now, though, no price was too high to pay in his quest to destroy Netscape.

Which raises the question of why he was so obsessed, given that Microsoft was making literally no money from Internet Explorer. The answer is rooted in all that rhetoric that was flying around at the time about the browser as a computing platform — about the Web effectively turning into a giant computer in its own right, floating up there somewhere in the heavens, ready to give a little piece of itself to anyone with a minimalist machine running Netscape Navigator. Such a new world order would have no need for a Microsoft Windows — perish the thought! But if, on the other hand, Microsoft could wrest the title of leading browser developer out of the hands of Netscape, it could control the future evolution of this dangerously unruly beast known as the World Wide Web, and ensure that it didn’t encroach on its other businesses.

That the predictions which prompted Microsoft’s downright unhinged frenzy to destroy Netscape were themselves wildly overblown is ironic but not material. As tech journalist Merrill R. Chapman has put it, “The prediction that anyone was going to use Navigator or any other browser anytime soon to write documents, lay out publications, build budgets, store files, and design presentations was a fantasy. The people who made these breathless predictions apparently never tried to perform any of these tasks in a browser.” And yet in an odd sort of way this reality check didn’t matter. Perception can create its own reality, and Bill Gates’s perception of Netscape Navigator as an existential threat to the software empire he had spent the last two decades building was enough to make the browser war feel like a truly existential clash for both parties, even if the only one whose existence actually was threatened — urgently threatened! — was Netscape. Jim Clark, Marc Andreessen’s partner in founding Netscape, makes the eyebrow-raising claim that he “knew we were dead” in the long run well before the end of 1996, when the Department of Justice declined to respond to an urgent plea on Netscape’s part to take another look at Microsoft’s business practices.

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of the conflict is just how long Netscape’s long run proved to be. It was in most respects David versus Goliath: Netscape in 1996 had $300 million in annual revenues to Microsoft’s nearly $9 billion. But whatever the disparities of size, Netscape had built up a considerable reservoir of goodwill as the vehicle through which so many millions had experienced the Web for the first time. Microsoft found this soft power oddly tough to overcome, even with a browser of its own that was largely identical in functional terms. A remarkable number of people continued to make the active choice to use Netscape Navigator instead of the passive one to use Internet Explorer. By October of 1997, one year after Microsoft brought out the big gun and bundled Internet Explorer right into Windows 95, its browser’s market share had risen as high as 39 percent — but it was Netscape that still led the way at 51 percent.

Yet Netscape wasn’t using those advantages it did possess all that effectively. It was not a happy or harmonious company: there were escalating personality clashes between Jim Clark and Marc Andreessen, and also between Andreessen and his programmers, who thought their leader had become a glory hound, too busy playing the role of the young dot.com millionaire to pay attention to the vital details of software development. Perchance as a result, Netscape’s drive to improve its browser in paradigm-shifting ways seemed to slowly dissipate after the landmark Navigator 2.0 release.

Netscape, so recently the darling of the dot.com age, was now finding it hard to make a valid case for itself merely as a viable business. The company’s most successful quarter in financial terms was the third of 1996 — just before Internet Explorer became an official part of Windows 95 — when it brought in $100 million in revenue. Receipts fell precipitously after that point, all the way down to just $18.5 million in the last quarter of 1997. By so aggressively promoting Internet Explorer as entirely and perpetually free, Bill Gates had, whether intentionally or inadvertently, instilled in the general public an impression that all browsers were or ought to be free, due to some unstated reason inherent in their nature. (This impression has never been overturned, as has been testified over the years by the failure of otherwise worthy commercial browsers like Opera to capture much market share.) Thus even the vast majority of those who did choose Netscape’s browser no longer seemed to feel any ethical compulsion to pay for it. Netscape was left in a position all too familiar to Web firms of the past and present alike: that of having immense name recognition and soft power, but no equally impressive revenue stream to accompany them. It tried frantically to pivot into back-end server architecture and corporate intranet solutions, but its efforts there were, as its bottom line will attest, not especially successful. It launched a Web portal and search engine known as Netcenter, but struggled to gain traction against Yahoo!, the leader in that space. Both Jim Clark and Marc Andreessen sold off large quantities of their personal stock, never a good sign in Silicon Valley.

Netscape Navigator was renamed Netscape Communicator for its 4.0 release in June of 1997. As the name would imply, Communicator was far more than just a browser, or even just a browser with an integrated email client and Usenet reader, as Navigator had been since version 2.0. Now it also sported an integrated editor for making your own websites from scratch, a real-time chat system, a conference caller, an appointment calendar, and a client for “pushing” usually unwanted content to your screen. It was all much, much too much, weighted down with features most people would never touch, big and bloated and slow and disturbingly crash-prone; small wonder that even many Netscape loyalists chose to stay with Navigator 3 after the release of Communicator. Microsoft had not heretofore been known for making particularly svelte software, but Internet Explorer, which did nothing but browse the Web, was a lean ballerina by comparison with the lumbering Sumo wrestler that was Netscape Communicator. The original Netscape Navigator had sprung from the hacker culture of institutional computing, but the company had apparently now forgotten one of that culture’s key dictums in its desire to make its browser a platform unto itself: the best programs are those that do only one thing, but do that one thing very, very well, leaving all of the other things to other programs.

Netscape Communicator. I’m told that there’s an actual Web browser buried somewhere in this pile. Probably a kitchen sink too, if you look hard enough.

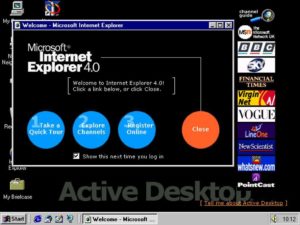

Luckily for Netscape, Internet Explorer 4.0, which arrived three months after Communicator, violated the same dictum in an even more inept way. It introduced what Microsoft called the “Active Desktop,” which let it bury its hooks deeper than ever into Windows itself. The Active Desktop was — or tried to be — Bill Gates’s nightmare of a Web that was impossible to separate from one’s local computer come to life, but with Microsoft’s own logo on it. Ironically, it blurred the distinction between the local computer and the Internet more thoroughly than anything the likes of Sun or Netscape had produced to date; local files and applications became virtually indistinguishable from those that lived on the Internet in the new version of the Windows desktop it installed in place of the old. The end result served mainly to illustrate how half-baked all of the prognostications about a new era of computing exclusively in the cloud really were. The Active Desktop was slow and clumsy and confusing, and absolutely everyone who was exposed to it seemed to hate it and rush to find a way to turn it off. Fortunately for Microsoft, it was possible to do so without removing the Internet Explorer 4 browser itself.

The dreaded Active Desktop. Surprisingly, it was partially defended on philosophical grounds by Tim Berners-Lee, not normally a fan of Microsoft. “It was ridiculous for a person to have two separate interfaces, one for local information (the desktop for their own computer) and one for remote information (a browser to reach other computers),” he writes. “Why did we need an entire desktop for our own computer, but only get little windows through which to view the rest of the planet? Why, for that matter, should we have folders on our desktop but not on the Web? The Web was supposed to be the universe of all accessible information, which included, especially, information that happened to be stored locally. I argued that the entire topic of where information was physically stored should be made invisible to the user.” For better or for worse, though, the public didn’t agree. And even he had to allow that “this did not have to imply that the operating system and browser should be the same program.”

The Active Desktop damaged Internet Explorer’s reputation, but arguably not as badly as Netscape’s had been damaged by the bloated Communicator. For once you turned off all that nonsense, Internet Explorer 4 proved to be pretty good at doing the rest of its job. But there was no similar method for trimming the fat from Netscape Communicator.

While Microsoft and Netscape, those two for-profit corporations, had been vying with one another for supremacy on the Web, another, quieter party had been looking on with great concern. Before the Web had become the hottest topic of the business pages, it had been an idea in the head of the mild-mannered British computer scientist Tim Berners-Lee. He had built the Web on the open Internet, using a new set of open standards; his inclination had never been to control his creation personally. It was to be a meeting place, a library, a forum, perhaps a marketplace if you liked — but always a public commons. When Berners-Lee formed the non-profit World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) in October of 1994 in the hope of guiding an orderly evolution of the Web that kept it independent of the moneyed interests rushing to join the party, it struck many as a quaint endeavor at best. Key technologies like Java and JavaScript appeared and exploded in popularity without giving the W3C a chance to say anything about them. (Tellingly, the word “JavaScript” never even appears in Berners-Lee’s 1999 book about his history with and vision for the Web, despite the scripting language’s almost incalculable importance to making it the dynamic and diverse place it had become by that point.)

From the days when he had been a mere University of Illinois student making a browser on the side, Marc Andreessen had blazed his own trail without giving much thought to formal standards. When the things he unilaterally introduced proved useful, others rushed to copy them, and they became de-facto standards. This was as true of JavaScript as it was of anything else. As we’ve seen, it began as a Netscape-exclusive feature, but was so obviously transformative to what the Web could do and be that Microsoft had no choice but to copy it, to incorporate its own implementation of it into Internet Explorer.

But JavaScript was just about the last completely new feature to be rolled out and widely adopted in this ad-hoc fashion. As the Web reached a critical mass, with Netscape Navigator and Internet Explorer both powering users’ experiences of it in substantial numbers, site designers had a compelling reason not to use any technology that only worked on the one or the other; they wanted to reach as many people as possible, after all. This brought an uneasy sort of equilibrium to the Web.

Nevertheless, the first instinct of both Netscape and Microsoft remained to control rather than to share the Web. Both companies’ histories amply demonstrated that open standards meant little to them; they preferred to be the standard. What would happen if and when one company won the browser war, as Microsoft seemed slowly to be doing by 1997, what with the trend lines all going in its favor and Netscape in veritable financial free fall? Once 90 percent or more of the people browsing the Web were doing so with Internet Explorer, Microsoft would be free to give its instinct for dominance free rein. With an army of lawyers at its beck and call, it would be able to graft onto the Web proprietary, patented technologies that no upstart competitor would be able to reverse-engineer and copy, and pragmatic website designers would no longer have any reason not to use them, if they could make their sites better. And once many or most websites depended on these features that were available only in Internet Explorer, that would be that for the open Web. Despite its late start, Microsoft would have managed to embrace, extend, and in a very real sense destroy Tim Berners-Lee’s original vision of a World Wide Web. The public commons would have become a Microsoft-branded theme park.

These worries were being bandied about with ever-increasing urgency in January of 1998, when Netscape made what may just have been the most audacious move of the entire dot.com boom. Like most such moves, it was born of sheer desperation, but that shouldn’t blind us to its importance and even bravery. First of all, Netscape made its browser free as in beer, finally giving up on even asking people to pay for the thing. Admittedly, though, this in itself was little more than an acceptance of the reality on the ground, as it were. It was the other part of the move that really shocked the tech world: Netscape also made its browser free as in freedom — it opened up its source code to all and sundry. “This was radical in its day,” remembers Mitchell Baker, one of the prime drivers of the initiative at Netscape. “Open source is mainstream now; it was not then. Open source was deep, deep, deep in the technical community. It never surfaced in a product. [This] was a very radical move.”

Netscape spun off a not-for-profit organization, led by Baker and called Mozilla, after a cartoon dinosaur that had been the company’s office mascot almost from day one. Coming well before the Linux operating system began conquering large swaths of corporate America, this was to be open source’s first trial by fire in the real world. Mozilla was to concentrate on the core code required for rendering webpages — the engine room of a browser, if you will. Then others — not least among them the for-profit arm of Netscape — would build the superstructures of finished applications around that sturdy core.

Alas, Netscape the for-profit company was already beyond saving. If anything, this move only hastened the end; Netscape had chosen to give away the one product it had that some tiny number of people were still willing to pay for. Some pundits talked it up as a dying warrior’s last defiant attempt to pass the sword to others, to continue the fight against Microsoft and Internet Explorer: “From the depths of Hell, I spit at thee!” Or, as Tim Berners-Lee put it more soberly: “Microsoft was bigger than Netscape, but Netscape was hoping the Web community was bigger than Microsoft.” And there may very well be something to these points of view. But regardless of the motivations behind it, the decision to open up Netscape’s browser proved both a landmark in the history of open-source software and a potent weapon in the fight to keep the Web itself open and free. Mozilla has had its ups and downs over the years since, but it remains with us to this day, still providing an alternative to the corporate-dominated browsers almost a quarter-century on, having outlived the more conventional corporation that spawned it by a factor of six.

Mozilla’s story is an important one, but we’ll have to leave the details of it for another day. For now, we return to the other players in today’s drama.

While Microsoft and Netscape were battling one another, AOL was soaring into the stratosphere, the happy beneficiary of Microsoft’s decision to give it an icon on the Windows 95 desktop in the name of vanquishing Netscape. In 1997, in a move fraught with symbolic significance, AOL bought CompuServe, its last remaining competitor from the pre-Web era of closed, proprietary online services. By the time Netscape open-sourced its browser, AOL had 12 million subscribers and annual profits — profits, mind you, not revenues — of over $500 million, thanks not only to subscription fees but to the new frontier of online advertising, where revenues and profits were almost one and the same. At not quite 40 years old, Steve Case had become a billionaire.

“AOL is the Internet blue chip,” wrote the respected stock analyst Henry Blodget. And indeed, for all of its association with new and shiny technology, there was something comfortingly stolid — even old-fashioned — about the company. Unlike so many of his dot.com compatriots, Steve Case had found a way to combine name recognition and a desirable product with a way of getting his customers to actually pay for said product. He liked to compare AOL with a cable-television provider; this was a comparison that even the most hidebound investors could easily understand. Real, honest-to-God checks rolled into AOL’s headquarters every month from real, honest-to-God people who signed up for real, honest-to-God paid subscriptions. So what if the tech intelligentsia laughed and mocked, called AOL “the cockroach of cyberspace,” and took an “@AOL.com” suffix on someone’s email address as a sign that they were too stupid to be worth talking to? Case and his shareholders knew that money from the unwashed masses spent just as well as money from the tech elites.

Microsoft could finally declare victory in the browser war in the summer of 1998, when the two browsers’ trend lines crossed one another. At long last, Internet Explorer’s popularity equaled and then rapidly eclipsed that of Netscape Navigator/Communicator. It hadn’t been clean or pretty, but Microsoft had bludgeoned its way to the market share it craved.

A few months later, AOL acquired Netscape through a stock swap that involved no cash, but was worth a cool $9.8 billion on paper — an almost comical sum in relation to the amount of actual revenue the purchased company had brought in during its lifetime. Jim Clark and Marc Andreessen walked away very, very rich men. Just as Netscape’s big IPO had been the first of its breed, the herald of the dot.com boom, Netscape now became the first exemplar of the boom’s unique style of accounting, which allowed people to get rich without ever having run a profitable business.

Even at the time, it was hard to figure out just what it was about Netscape that AOL thought was worth so much money. The deal is probably best understood as a product of Steve Case’s fear of a Microsoft-dominated Web; despite that AOL icon on the Windows desktop, he still didn’t trust Bill Gates any farther than he could throw him. In the end, however, AOL got almost nothing for its billions. Netscape Communicator was renamed AOL Communicator and offered to the service’s subscribers, but even most of them, technically unsophisticated though they tended to be, could see that Internet Explorer was the cleaner and faster and just plain better choice at this juncture. (The open-source coders working with Mozilla belatedly realized the same; they would wind up spending years writing a brand-new browser engine from scratch after deciding that Netscape’s just wasn’t up to snuff.)

Most of Netscape’s remaining engineers walked soon after the deal was made. They tended to describe the company’s meteoric rise and fall in the terms of a Shakespearean tragedy. “At least the old timers among us came to Netscape to change the world,” lamented one. “Getting killed by the Evil Empire, being gobbled up by a big corporation — it’s incredibly sad.” If that’s painting with rather too broad a brush — one should always run away screaming when a Silicon Valley denizen starts talking about “changing the world” — it can’t be denied that Netscape at no time enjoyed a level playing field in its war against Microsoft.

But times do change, as Microsoft was about to learn to its cost. In May of 1998, the Department of Justice filed suit against Microsoft for illegally exploiting its Windows monopoly in order to crush Netscape. The suit came too late to save the latter, but it was all over the news even as the first copies of Windows 98, the hotly anticipated successor to Windows 95, were reaching store shelves. Bill Gates had gotten his wish; Internet Explorer and Windows were now indissolubly bound together. Soon he would have cause to wish that he had not striven for that outcome quite so vigorously.

(Sources: the books Overdrive: Bill Gates and the Race to Control Cyberspace by James Wallace, The Silicon Boys by David A. Kaplan, Architects of the Web by Robert H. Reid, Competing on Internet Time: Lessons from Netscape and Its Battle with Microsoft by Michael Cusumano and David B. Yoffie, dot.con: The Greatest Story Ever Sold by John Cassidy, Stealing Time: Steve Case, Jerry Levin, and the Collapse of AOL Time Warner by Alec Klein, Fools Rush In: Steve Case, Jerry Levin, and the Unmaking of AOL Time Warner by Nina Munk, There Must be a Pony in Here Somewhere: The AOL Time Warner Debacle by Kara Swisher, In Search of Stupidity: Over Twenty Years of High-Tech Marketing Disasters by Merrill R. Chapman, Coders at Work: Reflections on the Craft of Programming by Peter Seibel, and Weaving the Web by Tim Berners-Lee. Online sources include “1995: The Birth of JavaScript” at Web Development History, the New York Times timeline of AOL’s history, and Mitchell Baker’s talk about the history of Mozilla, which is available on Wikipedia.)