Continental Europe is notable for its almost complete absence during the early years of the PC revolution. Even Germany, by popular (or stereotypical) perception a land of engineers, played little role; when PCs started to enter West German homes in large numbers in the mid-1980s, they were almost entirely machines of American or British design. Yet in some ways European governments were quite forward-thinking in their employment of computer technology in comparison to that of the United States. As early as 1978 the French postal service began rolling out a computerized public network called Minitel, which not only let users look up phone numbers and addresses but also book travel, buy mail-order products, and send messages to one another. A similar service in West Germany, Bildschirmtext, began shortly after, and both services thrived until the spread of home Internet access over the course of the 1990s gradually made them obsolete.

The U.S. had no equivalent to these public services. Yes, there was the social marvel that was PLATO, but it was restricted to students and faculty fortunate enough to attend a university on the network; The Source, but you had to both pay a substantial fee for the service and be able to afford the pricy PC you needed to access it; the early Internet, but it was also restricted to a relative technical and scientific elite fortunate enough to be at a university or company that allowed them access. It’s tempting to draw an (overly?) broad comparison here between American and European cultural values: the Americans were all about individual, personal computers that one could own and enjoy privately, while the Europeans treated computing as a communal resource to be shared and developed as a social good. But I’ll let you head further down that fraught path for yourself, if you like.

In this area as in so many others, Britain seemed stuck somewhere in the middle of this cultural divide. Although the British PC industry lagged a steady three years behind the American during the early years, from 1978 on there were plenty of eager PC entrepreneurs in Britain. Notably, however, the British government was also much more willing than the American to involve itself in bringing computers to the people. Margaret Thatcher may have dreamed of dismantling the postwar welfare state entirely and remaking the British economy on the American model, but plenty of MPs even within her own Conservative party weren’t ready to go quite that far. Thus the British post developed a Minitel equivalent of its own, Prestel, even before the German system debuted. But for the young British PC industry the most important role would be played by the country’s publicly-funded broadcasting service, the BBC — and not without, as is so typical when public funds mix with private enterprise, a storm of controversy and accusation.

Computers first turned up on the BBC in early 1980, when the network ran a three-part documentary series called The Silicon Factor just as the first Sinclair ZX80s and Acorn Atoms were reaching customers. It largely dealt with computing as an economic and social force, and wasn’t above a little scare mongering — “Did you know the micro would cut out so-and-so many skilled jobs by 1984?” The following year brought two more specialized programs: Managing the Micro, a five-parter aimed at executives wanting to understand the potential role of computers in business; and the two-part Technology for Teachers, about computers as educational tools. But even as the latter two series were being developed and coming to the airwaves, one within the BBC was dreaming of something grander. Paul Kriwaczek, a producer who had worked on The Silicon Factor, asked the higher-ups a question: “Don’t we have a duty to put some of the power of computing into the public’s hands rather than just make programs about computing?” He envisioned a program that would not treat computing as a purely abstract social or business phenomenon. It would rather be a practical examination of what the average person could do with a PC, right now — or at least in the very near future.

The idea was very much of its time, spurred equally by fear and hope. With all of the early innovation having happened in America, the PC looked likely to be another innovation — and there sure seemed to have been a lot of them this century — with which Britain would have little to do. On the other hand, however, these were still early days, and there did already exist a network of British computing companies and the enthusiasts they served. Properly stoked, and today rather than later, perhaps they could form the heart of new, home-grown British computer industry that would, at a minimum, prevent the indignity of seeing Britons rely, as they already did in so many other sectors, on imported products. At best, the PC could become a new export industry. With the government forced to prop up much of the remaining British auto industry, with many other sectors seemingly on the verge of collapse, and with the economy in general in the crapper, the country could certainly use a dose of something new and innovative. By interesting ordinary Britons in computers and spurring them to buy British models today, this program could be a catalyst for the eager but uncertain British PC industry as well as the incubator of a new generation of computing professionals.

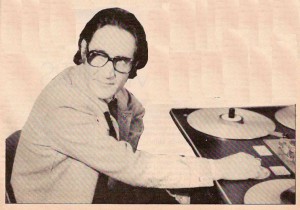

Much to Kriwaczek’s own surprise, his proposed program landed right in his lap. The BBC approved a new ten-part series to be called Hands-On Micros. Under the day-to-day control of Kriwaczek, it would air in the autumn of 1981 — in about one year’s time. His advocacy for the program aside, Kriwaczek was the obvious choice among the BBC’s line producers. He had grown interested in PCs some months earlier, when he had worked on The Silicon Factor and, perhaps more importantly, when he had stumbled upon a copy of the early British hobbyist magazine Practical Computing. Now he had a Nascom at home which he had built for himself. A jazz saxophonist and flautist by a former trade, he now spent hours in his office trying to get the machine to play music that could be recognized as such. (“My wife and family aren’t very keen on the micro,” he said in a contemporary remark that sounds like an understatement.) Working with another producer, David Allen, Kriwaczek drafted a plan for the project that would make it more substantial than just another one-off documentary miniseries. There would be an accompanying book, for one thing, which would go deeper into many of the topics presented and offer much more hands-on programming instruction. And, strangely and controversially, there would also be a whole new computer with the official BBC stamp of approval.

To understand what motivated this seemingly bizarre step, we should look at the British PC market of the time. It was a welter of radically divergent, thoroughly incompatible machines, in many ways no different from the contemporary American market, but in at least one way even more confused. In the U.S. most PC-makers sourced their BASIC from Microsoft, which remained relatively consistent from machine to machine, and thus offered at least some sort of route to program interchange. The British market, however, was not even this consistent. While Nascom did buy a Microsoft BASIC, both Acorn and Sinclair had chosen to develop their own, highly idiosyncratic versions of the language, and a survey of other makers revealed a similar jumble. Further, none of these incompatible machines was precisely satisfactory in the BBC’s eyes. As a kit you had to build yourself, the Nascom was an obvious nonstarter. The Acorn Atom came pre-assembled, but with a maximum of 12 K of memory it was a profoundly limited machine. The Sinclair ZX80 and ZX81 were similarly limited, and also beset by that certain endemic Sinclair brand of shoddiness that left users having to glue memory expansions into place to keep them from falling out of their sockets and half expecting the whole contraption to explode one day like the Black Watch of old. The Commodore PET was the favorite of British business, but it was very expensive and American to boot, which kind of defeated the program’s purpose of goosing British computing. So, the BBC decided to endorse a new PC built to their requirements of being a) British; b) of solid build quality; c) possessed of a relatively standard and complete dialect of BASIC; and d) powerful enough to perform reasonably complex, hopefully even useful tasks. The idea may seem a more reasonable one in this light to all but the most laissez-faire among you. The way they chose to pursue it, though, was quite problematic.

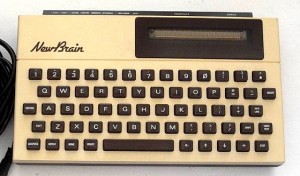

As you may remember from a previous post, Clive Sinclair and Chris Curry had worked together at Sinclair’s previous company, Sinclair Radionics, before going on to found Sinclair Research and Acorn Computers respectively. In the wake of the Black Watch fiasco, the National Enterprise Board of the British government had stepped in to take over Sinclair Radionics and prevent the company from failing. Sinclair, however, proved impossible to work with, and was soon let go. The NEB shuttered what was left of Sinclair Radionics. But they passed its one seemingly viable project, a computer called the NewBrain which Sinclair had conceived but then lost interest in, to another NEB-owned concern, Newbury Laboratories. As the BBC’s grand computer literacy project was being outlined, the NewBrain was still at Newbury and still inching slowly toward release. If Newbury could just get the thing finished, the NewBrain should meet all of the BBC’s requirements for their new computer. They decided it was the computer for them. To preserve some illusion of an open bidding process, they wrote up a set of requirements that coincidentally corresponded exactly with the proposed specifications of the NewBrain, then slipped out the call for bids as quietly as they possibly could. Nobody outside Newbury noticed it, and even if they had, it would have been impossible to develop a computer to those specifications in the tiny amount of time the BBC was offering. The plan had worked perfectly. It looked like they had their new BBC computer.

But why was the BBC so fixated on the NewBrain? It’s hard not to see bureaucratic back-scratching in the whole scheme. Another branch of the British bureaucracy, the National Enterprise Board, had pissed away a lot of taxpayer money in the failed Sinclair Radionics rescue bid. If they could turn the NewBrain into a big commercial success — something of which the official BBC endorsement would be a virtual guarantee — they could earn all of that money back through Newbury, a company which had been another questionable investment. Some damaged careers would certainly be repaired and even burnished in the process. That, at any rate, is how the rest of the British PC industry saw the situation when the whole process finally came to light, and it’s hard to come to any other conclusion today.

Just a few months later, the BBC looked to have hoisted themselves from their own petard. It had now become painfully clear that Newbury was understaffed and underfunded. They couldn’t finish developing the NewBrain in the time allotted, and couldn’t arrange to manufacture it in the massive quantities that would be required even if they did. It was just as this realization was dawning that they received two very angry letters, one from Clive Sinclair and one from Chris Curry at Acorn. Curry had come across an early report about the project in his morning paper, describing the plan for a BBC-branded computer and the “bidding process” and giving the specifications of the computer that had “won.” He called Sinclair, with whom he still maintained polite if strained relations. Sinclair hadn’t heard anything about the project either. Putting their heads together, they deduced that the machine in question must be the NewBrain, and why it must have been chosen. Thus the angry letters.

What happened next would prompt even more controversy. Curry, who had sent his letter more to vent than anything else, was stunned to receive a call from a rather sheepish John Radcliffe, an executive producer on the project, asking if the BBC could come to Acorn’s Cambridge offices for a meeting. Nothing was set in stone, Radcliffe carefully explained. If Curry had something he wanted to show the BBC, the BBC was willing to consider it. Sinclair, despite being known as Mr. Computer to the British public, received no such call. The reasons he didn’t aren’t so hard to deduce. Sinclair had screwed the National Enterprise Board badly in the Sinclair Radionics deal by being impossible to work with and finally apparently deliberately sabotaging the whole operation so that he could get away and begin a new company. It’s not surprising that his reputation within the British bureaucracy was none too good. On a less personal level, there were the persistent quality-control problems that had dogged just about everything Sinclair had ever made. The BBC simply couldn’t afford to release an exploding computer.

At the meeting, Curry first tried to sell Radcliffe on Acorn’s existing computer, the Atom, but even at this desperate juncture Radcliffe was having none of it. The Atom was just too limited. Could he propose anything else? “Well,” said Curry, “We are developing this new machine we call the Proton.” “Can you show it to me?” asked Radcliffe. “I’m afraid it’s not quite ready,” replied Curry. “When can we see a working prototype?” asked Radcliffe. It was already December 1980; time was precious. It was also a Monday. “Come back Friday,” said Curry.

The Acorn team worked frantically through the week to get the Proton, still an unfinished pile of wires, chips, and schematics, into some sort of working shape. A few hours before the BBC’s scheduled return they thought they had everything together properly, but the machine refused to boot. Hermann Hauser, the Austrian Cambridge researcher with whom Curry had started Acorn, made a suggestion: “It’s very simple — you are cross-linking the clock between the development system and the prototype. If you just cut the link it will work.” After a bit of grumbling the team agreed, and the machine sprang to life for the first time just in time for the BBC’s visit. Soon after Acorn officially had the contract, and along with it an injection of £60,000 to set up much larger manufacturing facilities. The Acorn Proton was now the BBC Micro; Acorn was playing on a whole new level.

Acorn and the BBC were fortunate in that the Proton design actually dovetailed fairly well with the BBC’s original specifications. In places where it did not, either the specification or the machine was quietly modified to make a fit. Most notably, the BASIC housed in ROM was substantially reworked to conform better to the BBC’s wish for a fairly standard implementation of the language in comparison to the very personalized dialects both Acorn and Sinclair had previously favored. After the realities of production costs sank in, the decision was made to produce two BBC Micros, the Model A with just 16 K of memory and the Model B with the full 32 K demanded by the original specification and some additional expansion capabilities. The Model B also came with an expanded suite of graphics modes, offering up to 16 colors at 160 X 256, a monochrome 640 X 256 mode, and 80-column text, all very impressive even by comparison with American computers of the era. It would turn out to be by far the more popular model. At the heart of both models was a 6502 CPU which was clocked at 2 MHz rather than the typical 1 MHz of most 6502-based computers. Combined with an innovative memory design that allowed the CPU to always run at full speed, with no waiting for memory access, this made the BBC Micro quite a potent little machine by the standards of the early 1980s. By way of comparison, the 3 to 4 MHz Z80s found in many competitors like the Sinclair machines were generally agreed to have about the same overall processing potential as a 1 MHz 6502, despite the dramatically faster clock speed, due to differences in the designs of the two chips.

By quite a number of metrics, the BBC Micro would be the best, most practical machine the domestic British industry had yet produced. Unfortunately, all that power and polish would come with a price. The BBC had originally dreamed of a sub-£200 machine, but that quickly proved unrealistic. The projected price steadily crept upward as 1981 wore on. When models started arriving in shops at last, the price was £300 for the Model A and £400 for the Model B, much more expensive than the original plans and much, much more than Sinclair’s machines. Considering that buying the peripherals needed to make a really useful system would nearly double the likely price, these figures to at least some extent put the lie to the grand dream of the BBC Micro as the computer for the everyday Briton — a fact that Clive Sinclair and others lost no time in pointing out. A roughly equivalent foreign-built system, like, say, a Commodore PET, would still cost you more, but not all that much more. The closest American comparison to the BBC Micro is probably the Apple II. Like that machine, the BBC Micro would become the relative Cadillac of 8-bit British computers: better built and somehow more solid-feeling than the competition, even as its raw processing and display capabilities grew less impressive in comparison — and, eventually, outright outdated — over time.

As the BBC Micro slowly came together, other aspects of the project also moved steadily forward. By the spring of 1981 three authors were hard at work writing the book, and Kriwaczek and Allen were traveling around the country collecting feedback from schools and focus groups on a 50-minute pilot version of the proposed documentary. With it becoming obvious that everyone needed a bit more time, the whole project was reluctantly pushed back three months. The first episode of the documentary, retitled The Computer Programme, was now scheduled to air on January 11, 1982, with the book and the computer also expected to be available by that date.

And now what had already been a crazily ambitious project suddenly found itself part of something even more ambitious. A Conservative MP named Kenneth Baker shepherded through Parliament a bill naming 1982 Information Technology Year. It would kick off with The Computer Programme in a plum time slot on the BBC, and end with a major government-sponsored conference at the Barbican Arts Centre. In between would be a whole host of other initiatives, some of which, like the issuing of an official IT ’82 stamp by the post office, were probably of, shall we say, symbolic value at best. Yet there were also a surprising number of more practical initiatives, like the establishment of a network of Microsystem Centres to offer advice and training to businessmen and IT Centres to train unemployed young people in computer-related fields. There would also be a major push to get PCs into every school in Britain in numbers that would allow every student a reasonable amount of hands-on time. All of these programs — yes, even the stamp — reflected the desire of at least some in the government to make Britain the IT Nation of the 1980s, to remake the struggling British economy via the silicon chip.

When the first step in their master plan debuted at last on January 11, everything was not quite as they might have wished it. The BBC’s programming department reneged on their promises to give the program a plum time spot. Instead it aired on a Monday afternoon and was repeated the following Sunday morning, meaning ratings were not quite what Kriwaczek and his colleagues might have hoped for. And, although Acorn had been taking orders for several months, virtually no one other than a handful of lucky magazine reviewers had an actual BBC Micro to use to try out the snippets of BASIC code that the show presented. Even with the infusion of government cash, Acorn was struggling to sort out the logistics of producing machines in the quantities demanded by the BBC, while also battling teething problems in the design and some flawed third-party components. BBC Micros didn’t finally start flowing to customers until well into spring — ironically, just as the last episodes of the series were airing. Thus Kriwaczek’s original dream of an army of excited new computer owners watching his series from behind the keyboards of their new BBC Micros didn’t quite play out, at least in the program’s first run.

In the long run, however, the BBC Micro became a big success, if not quite the epoch-defining development the BBC had originally envisioned. Its relatively high price kept it out of many homes in favor of cheaper machines from Sinclair and Commodore, but, with the full force of the government’s patronage (and numerous government-sponsored discounting programs) behind it, it became the most popular machine by far in British schools. In this respect once again, the parallels with the Apple II are obvious. The BBC Micro remained a fixture in British schools throughout the 1980s, the first taste of computing for millions of schoolchildren. It was built like a tank and, soon enough, possessed of a huge selection of educational software that made it ideal for the task. By 1984 Acorn could announce that 85% of computers sold to British schools were BBC Micros. This penetration, combined with more limited uptake in homes and business, was enough to let Acorn sell more than 1.5 million of them over more than a decade in production.

As for the butterfly flapping its wings which got all of this started: The Computer Programme is surprisingly good, in spite of a certain amount of disappointment it engendered in the hardcore hobbyist community of the time for its failure to go really deeply into the ins and outs of programming in BASIC and the like (a task for which video strikes me as supremely ill-suited anyway). At its center is a well-known BBC presenter named Chris Serle. He plays the everyman, who’s guided (along with the audience, of course) through a tour of computer history and applications and a certain amount of practical nitty-gritty by the more experienced Ian McNaught-Davis. It’s a premise that could easily wind up feeling grating and contrived, but the two men are so pleasant and natural about it that it mostly works beautifully. Rounding out the show are a field reporter, Gill Neville, who delivers a human-interest story about practical uses of computers in each episode; and “author and journalist” Rex Malik, who concludes each episode with an Andy Rooney-esque “more objective” — read, more crotchety — view on all of the gee-whiz gadgetry and high hopes that were on display in the preceding 22 minutes.

There’s a moment in one of the episodes that kind of crystallizes for me what makes the program as a whole so unique. McNaught-Davis is demonstrating a simple BASIC program for Serle. One of the lines is an INPUT statement. McNaught-Davis explains that when the computer reaches this line it just sits there checking the keyboard over and over for input from the user. Serle asks whether programs always work like that. Well, no, not always, explains McNaught-Davis… there are these things called interrupts on more advanced systems which can allow the CPU to do other things, to be notified automatically when a key press or some other event needs its attention. He then draws a beautiful analogy: the BASIC program is like someone who has a broken doorbell and is expecting guests. He must manually check the door over and over. An interrupt-driven system is the same fellow after he’s gotten his doorbell fixed, able to read or do other things in his living room and wait for his guests to come to him. The fact that McNaught-Davis acknowledges the complexity instead of just saying, “Yes, sure, just one thing at a time…” to Serle says a lot about the program’s refusal to dumb down its subject matter. Its decision not to pursue this strange notion of interrupts too much further, meanwhile, says a lot about the accompanying concern that it not overwhelm its audience. The BBC has always been really, really good at walking that line; The Computer Programme is a shining example of that skill.

Indeed, The Computer Programme can be worthwhile viewing today even for reasons outside of historical interest or kitsch value. Anyone looking for a good general overview of computers and how they work and what they can and can’t do could do a lot worse. I meant to just dip in and sample it here and there, but ended up watching the whole series (not that historical interest and kitsch value didn’t also play a factor). If you’d like to have a look for yourself, the whole series is available on YouTube thanks to Jesús Zafra.