As a kid, I absolutely loved time-travel stories. I devoured Quantum Leap and Poul Anderson’s Time Patrol, and later in adulthood was very enamored with Connie Willis’s more sophisticated takes on the tropes. As cool science-fictional concepts go, time travel is pretty hard to top. By comparison every other genre of story is limited, bound to whatever milieu the author has chosen or invented. But time travel lets you go hopscotching through the universe — or a multiplicity of them — within the bounds of a single volume.

It also makes a pretty darn appealing premise for an adventure game, maybe even more so than for traditional fiction, what with setting being the literary element adventures do best. And indeed, time travel forms its own lively adventure sub-genre which just happens to include some of my very favorites. Time Zone does not make that list, but it is the first major text adventure to really explore the genre. Considering what a natural fit it is for an adventure game, I’m only surprised that a game like Time Zone took this long to appear. (And yes, I know I’m opening myself up to long lists of obscure or amateur titles that did time travel before Time Zone. By all means, post ’em if you got ’em. But as a professional adventure with a full-fledged time-hopping premise, I’d say Time Zone is probably worthy of recognition as the first text adventure to really go all in for time-travel fiction of the sort I knew as a kid.)

Time-travel stories may be written out of fascination with the intrinsic coolness of time travel itself, but they do often need some sort of framing premise and conflict to motivate their heroes. Time Zone goes with a B-movie riff on 2001: A Space Odyssey. It is the “dawn of man,” echoes the Time Zone manual, and mankind is being observed with interest by an advanced alien race, the Neburites. Here, however, the aliens are evil, and get pissed off as the centuries go by and mankind’s essential badassitude asserts itself:

The year is 4081. The Earth is a fast-paced, highly technological society. The advancement of Earth in the last 2000 years is an amazement to Earth historians and a constant source of pride to Earth scientists. The Neburites, though, feel quite the opposite.

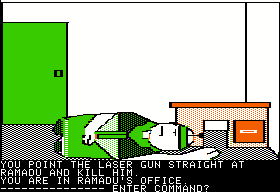

In the 2000 years since our last glimpse of the extraterrestrials they have advanced little, and their jealousy for the Earth’s advancement has grown to a mad fervor. The evil Neburite ruler Ramadu fears that the Earth will very soon become the superior race in the galaxy. This must not happen. His plan is to strike now, before the Earth is advanced enough to defend itself against an attack. So Ramadu has built an awesome ray gun, and aimed it directly at the distant Earth.

It seems that unless something is done, if Ramadu is not stopped and his weapons destroyed, Earth will never see the year 4082.

Stopping him is, of course, a job for you, an everyday Earthling living in 1982, given to you along with a time machine by “a terrestrial guardian or keeper.”

It’s never explained just why you were chosen rather than someone from, you know, the year 4081 who might consider the Earth’s pending destruction a more urgent problem, nor why this mission needs to involve all this time travel at all. You must visit dozens of times and places to collect the equipment you’ll need to confront Ramadu on his home planet in 4081 — exotic stuff like a hammer, a knife, a rope, and a damn rock(!). It would be a lot easier and faster to pop into your house — the time machine just appeared in your back yard, after all — or at worst down the street to the local hardware store to collect these trinkets and be on your way directly to Ramadu.

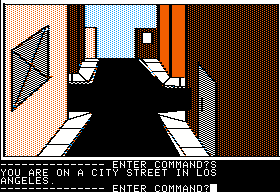

To some extent these absurdities are part and parcel of adventure gaming even today. (If you somehow lose the walking stick that is key to many puzzles in my own game The King of Shreds and Patches, why can’t you just go to a shop and buy another one?) Even today games often drag and contort their stories, not without split seams and shrieks of pain, into shape to accommodate their technical affordances. As a collection of smaller adventures bound together with bailing wire and duct tape, Time Zone has no notion of global state other than through the objects the player is carrying with her, which she obtained by solving various zones, just as Wizardry has no way of controlling for winning other than by looking to see whether the party is carrying the amulet they could only obtain by taking out Werdna. The necessary suspension of disbelief just seems somehow more extreme in Time Zone, as, for example, when I park my time machine on a city street in the middle of downtown London without anyone seeming to notice or care.

But, yes, you can say I’m just anachronistically poking holes in a game running on very limited technology — except that Infocom released a game at the same time that showed that a reasonably consistent, believable premise and setting was very possible even with 1982 technology. (More on that in a future post.)

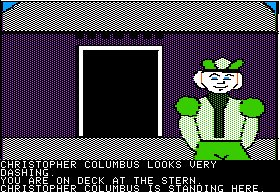

It’s not really surprising given the simplistic story and world model, but it is interesting to note the lack of many traditional time-travel tropes and concerns in Time Zone, the questions and paradoxes that do almost as much as the multiplicity of settings time travel offers to make it such a fun premise for a story (or a game). For instance, there’s no thought at all given to what happens if you change history. I suppose thought is not really needed, first of all because many zones have nothing interesting really going on anyway. For those that do, alteration of history is prevented by what Carl Muckenhoupt (whose own posts on Time Zone I highly recommend as companions to this one) calls “the poverty of the game engine.” The parser understands very little beyond what you have to do to solve the game, meaning that if you try to do something to mess with history — like, say, kill Christopher Columbus — you’re not going to be able to communicate your idea anyway.

The one place where Time Zone does nod toward traditional time-travel concerns is in not letting you carry objects back in time to a point before they were invented; if you try it, the anachronistic objects are destroyed. This of course provides Roberta Williams with a way of gating her puzzle design, preventing the player from using an obviously applicable item from solving this or that puzzle. It can also be very annoying, not only because it’s all too easy to be careless and lose track of what you’re carrying where, but also because it’s not always clear to the player — or, I strongly suspect given the countless historical gaffes in the game, to Roberta either — just when an item was invented, and thus just where the (time)line of demarcation really lies. In the small blessings department, the game does at least tell you when objects are destroyed this way. Given the era and the designer, one could easily imagine it keeping mum and letting you go quite a long way before figuring out you’ve made your game unwinnable.

But I should outline the general structure of the game before we go any further. From your home base that is literally your contemporary home, you can travel to each of the seven continents in any of five times — 50 BC, 1000 AD, 1400 AD, 1700 AD, 2082 AD — to collect what you need for the climax on Neburon in 4082 AD. (The manual says 4081, but it seems to have been written back when the game was still expected to ship in 1981 — thus the neat 2100-year gap.) Oh, and you can also visit 400 million BC, but only in one location. It’s explained as being thus limited because this was before the continents as we know them came into being. The same is also claimed to be true, bizarrely, of 10,000 BC (obviously there were no geologists around On-Line). Not all of the zones need to be visited; some serve only as red herrings. In what is, depending on your point of view, either a ripoff or the funniest joke in the game (or both), Antarctica in every single time consists of just a single location. You can only get out of your time machine, say, “Gee, it’s too cold here,” and climb back inside.

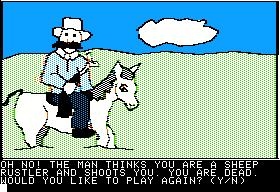

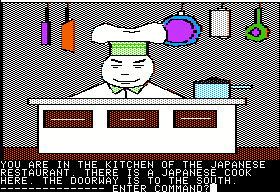

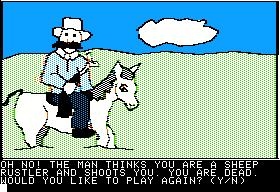

Some of the zones contain historical characters drawn straight from grade-school history books, giving the game (like so much of Roberta Williams’s work) a feel of children’s literature.

If you’ve been paying attention, you’ll note that Time Zone is not exactly rigorous about putting these characters precisely when they belong. It’s kind of tough to know to what extent Roberta messes with chronology just to be able to fit in all the cool stuff she wants to given just five time periods in which to put it all — Columbus certainly seems like a must-have, even if he is displaced by 92 years — and to what extent it’s all down to sloppy or nonexistent research. In her interview with Computer Gaming World to promote Time Zone, Roberta mentions an error she made, placing a rhea bird in Australia rather than South America. She explains the error away more disingenuously (or is this supposed to be funny?) in the manual:

To make a more interesting and challenging adventure, we have made some minor changes. For example, at one point in the game (I won’t say where) we have placed a rhea egg where you will never find a rhea bird. Anyone knowledgeable in ornithology knows that a rhea bird belong in South America (which is not where it is). This type of thing happens from time to time in Time Zone.

Worrying so much over such a minor point leaves one thinking that Time Zone‘s history must be rigorous indeed. Um, no. In addition to thinking that Pangaea still existed in 10,000 BC, the game also thinks that man invented fire in 10,000 BC. (In fact, it lets you be the one who invents fire, creating all sorts of timeline repercussions — if the game was more interested in such things, that is).

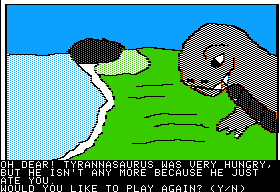

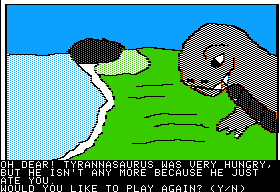

And it places brontosauruses (from the Jurassic period) and tyrannosauruses (from the Cretaceous) together in 400 million BC, hundreds of millennia too early for either. And then there’s Napoleon ruling in 1700 AD.

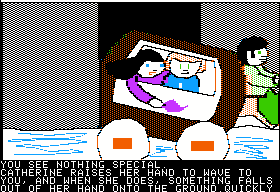

It’s hard for me to attribute this to the need to have cool stuff, because Louis XIV’s France was a pretty interesting historical moment in its own right. And your mission in this zone is to collect a comb and some perfume, which fits better with the Sun King’s effete court than with the more martial Napoleon. So, I must reluctantly conclude that Roberta doesn’t know her Louis XIV from her Napoleon. She also thinks that Saint Petersburg is in Asia, and that Peter the Great was the husband of Catherine the Great. “History books aren’t a lot of fun,” she asserts in the manual. Which kind of begs one to wonder why someone who doesn’t like history books is writing a game about history.

Time Zone has always had a reputation as a fearsomely unfair and difficult game. That’s true enough, but it’s not universally true when you look at it in a granular way. Many — probably most — of the puzzles break down into a few repeated archetypes, such as trading one fairly obvious item for another item.

There’s even a limited but surprising amount of kindness (or “user friendliness,” as the manual says over and over; presumably that term had just come into vogue). In addition to the game’s being kind enough to tell you when you lose an item in the timestream, the inventory limit, while present, is a very generous 16 items or so. And there is only one maze, if we restrict the term to rooms that are not laid out so that going north after going south gets you back where you started.

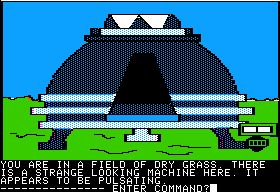

There are, however, large, tedious-to-map grids of empty rooms in virtually every zone you visit, and the game never tells you which exits from a location are available, forcing you to rely on trial and error. (Thank God the Hi-Res engine doesn’t support diagonal exits.) Indeed, Time Zone may have the shabbiest ratio of rooms to things to actually do in them in adventure-game history. By my count there are 57 items in the game, about the same as each of the first two Zork games — but spread over more than 1300 rooms. If anything the ratio feels even worse than that, as you wander through endless “pastures,” “meadows,” “fields,” and “city streets.” Actually playing Time Zone feels not like a grand journey through history, but rather a long slog through a whole bunch of nothing. No wonder poor Terry Pierce was reduced to tears at having to draw this monotony.

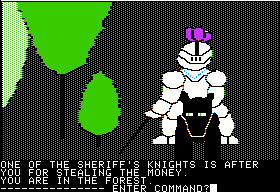

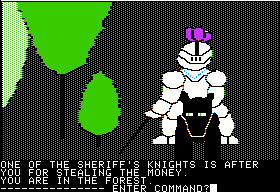

To relieve the boredom, entering some of these otherwise meaningless locations leads to instant death. The only way to solve many of these “puzzles” is to learn from the deaths and not enter that location again.

Some of the pictures are pretty nice, up to the standard of the earlier Hi-Res Adventures. Others show the strain of drawing 1400 pictures in eight months; they look pretty bad.

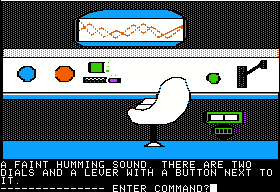

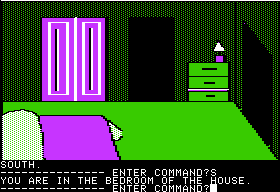

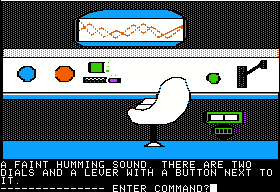

Something that’s often overlooked about the Hi-Res Adventures today is that they are not simply text adventures with illustrations, after the style of, say, the Magnetic Scrolls games of the later 1980s. Right from Mystery House there was an element of interactivity to their graphics: drop an item in an area and you would see it there; open a door and you would see it open onscreen; etc. That’s quite impressive. However, occasionally, just occasionally, Roberta decides to put essential information into the picture rather than bothering to describe it in text. Because this happens relatively seldom, and because there’s so much else in those pictures that isn’t implemented in the game, these occasions are devilishly easy to miss entirely.

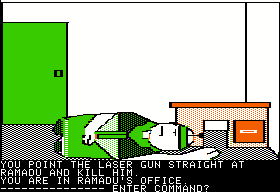

In the picture below, that little green thing at the bottom right that looks like an air vent is an essential oxygen mask — apparently for a person with a very weirdly shaped head, but that’s another issue — that’s going to get destroyed if we go back in time with it in the time machine with us.

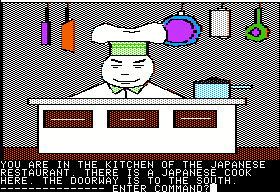

Nothing in the picture below is implemented except one of the drawers, which contains a knife that you need.

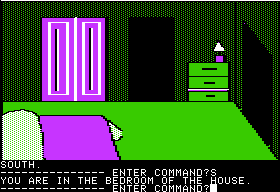

Only the cabinet is implemented below, which… you know the drill.

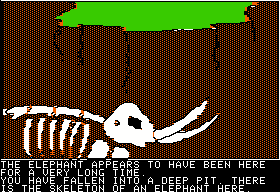

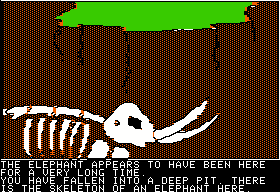

And the tusks of the elephant skeleton are implemented as separate objects that can be pried out and taken, something I’d never suspect in a million years.

All of this is frustrating in the extreme, but none of it is really that different from the other Hi-Res Adventures. What makes Time Zone so untenable, and leads to its reputation for difficulty and cruelty, is the combinatorial-explosion factor. There’s a pretty fixed order in which you need to work your way through the zones, using items found in one to solve puzzles in the next. Yet the game gives no clue whatsoever what that order must be, leaving you hopelessly at sea about where to go next or what to work on. (And then of course if you miss something like one of the above…) By late in the game you’ll have a full inventory plus a whole collection of extra objects piled outside your time machine, and won’t even know what to take with you from zone to zone.

Throw in all of the other annoyances — the pointless sudden deaths; the huge empty maps; the items and entire zones that serve only as red herrings; the uncertainty about what you can and can’t interact with; the obstinate parser; and just a few howlingly bad puzzles to top it all off — and the result is just excruciating. Theoretically this game could be solved, but really, why would you want to? Anyone willing to put this amount of methodical, tedious work in for so little positive feedback might be better off doing something that benefits mankind, or at least earns her a paycheck.

Or maybe it can’t be solved. It wouldn’t be a Roberta Williams game without a couple of really terrible puzzles. One of those is found in Asia (should be Europe, but why quibble?) in 1700 AD, where you have to wait outside Catherine the Great’s castle for five turns for no apparent reason for her to emerge with hubby Peter the Great and drop a hat pin.

This is made especially annoying by the fact that the game doesn’t even have a WAIT verb; you have to fiddle around with endless LOOKs and the like to get the turns to pass. (If you construed from the lack of WAIT that there would be no puzzle mechanics involving time, the joke’s on you.)

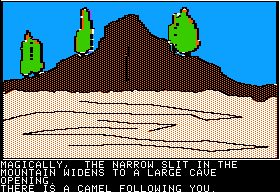

The other crowning jewel is the mountainside in the Asia of 1000 AD where you must type a totally unmotivated OPEN SESAME.

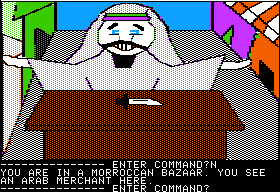

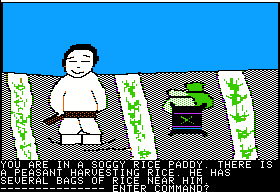

Puzzles aside, Time Zone just feels a bit amateurish and sloppy most of the time. Like a piece of fiction from a beginning writer, one senses that no one is in control of its tone or message, which veer about wildly. Nowhere is this more painful than in its depictions of the non-white natives of the zones, which come off as hilariously racist — but, I’m sure, unintentionally so.

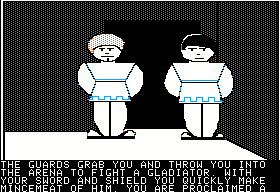

There are also weird occasions when the “children’s book” tone suddenly gives way to thoughtless violence.

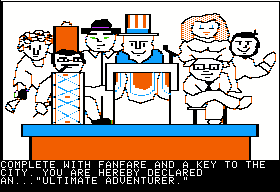

So, no, Time Zone is not a very good game. The climax on Neburon, which takes two disk sides by itself, is actually the strongest part, full of sudden deaths and empty rooms but also possessed of a forward narrative drive and sense of tension that was still rare in this era, as you penetrate deeper and deeper into the alien base. If released on its own, it would have stood up as possibly the best of the Hi-Res line. As it is, though, it comes at the end of such an exhausting slog that it’s hard to really appreciate. By the time you see the victory screen — which, incidentally, makes no sense; why are the people in your home town of 1982 celebrating a victory you won in 4082? — you’re just glad it’s over, just like the team who made it were when they finally got it out the door.

Sometimes, as The Prisoner taught us, the best way to win is not to play. Time Zone is perhaps doubly disappointing because the premise has so much potential. But neither the technology nor the designer were really equipped to realize such an ambitious idea, and certainly not in the time allowed. Still, Time Zone is of undeniable historical significance, so I have the Apple II disk images and the manual for those of you who’d like to dive in.

Next time: a bit about the aftermath of Time Zone before we move on to something else.