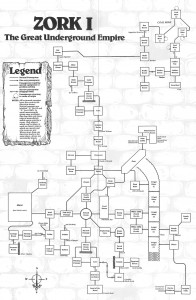

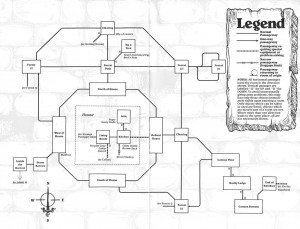

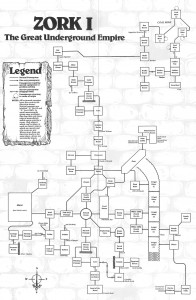

Today we’ll tackle the meat of Zork‘s Great Underground Empire, shown on the map below.

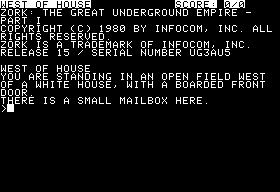

Exploring south from the cellar where we left off yields our second treasure and our first way out of the underground; we can carry exactly two items out with us via the fireplace in the living room of the white house. (But we can’t go back down that way; “ONLY SANTA CLAUS CLIMBS DOWN CHIMNEYS,” the game tells us, in a classic bit of adventure-game logic.) As we explore we’ll continue to find more and more — and more and more convenient — means of ingress and egress. Eventually, even the unknown nasty who keeps closing and barring the trapdoor behind us will stop it.

We also find a second note — oops, an “OWNER’s MANUAL” — south of the cellar. It conveys some of the wonder of this little, functioning world Infocom have constructed.

>EXAMINE PAPER

CONGRATULATIONS!

YOU ARE THE PRIVILEGED OWNER OF A

GENUINE ZORK GREAT UNDERGROUND EMPIRE

(PART I), A SELF CONTAINED AND SELF

MAINTAINING UNIVERSE. IF USED AND

MAINTAINED IN ACCORDANCE WITH NORMAL

OPERATING PRACTICES FOR SMALL UNIVERSES,

ZORK WILL PROVIDE MANY MONTHS OF

TROUBLE-FREE OPERATION. PLEASE CHECK

WITH YOUR DEALER FOR PART II AND OTHER

ALTERNATE UNIVERSES.

Like the title page shown in my previous post, the note also shows that Infocom were also already planning at least a Zork 2 at this stage, even if their naming rubric could still use some work. More interestingly, it also shows that they were already envisioning parlaying ZIL and the Z-Machine into a whole line of other, original games. In including an advertisement for other games within this one, Infocom were following the lead of Scott Adams, who always seemed to find space to plug one or two other current or upcoming games even within his tiny 16 K creations.

When we proceed north from the cellar, we run into a sort of perfect storm of bad luck.

>N

THE TROLL ROOM

THIS IS A SMALL ROOM WITH PASSAGES TO

THE EAST AND SOUTH AND A FORBIDDING HOLE

LEADING WEST. BLOODSTAINS AND DEEP

SCRATCHES (PERHAPS MADE BY AN AXE) MAR

THE WALLS.

A NASTY-LOOKING TROLL, BRANDISHING A

BLOODY AXE, BLOCKS ALL PASSAGES OUT OF

THE ROOM.

A SEEDY-LOOKING INDIVIDUAL WITH A LARGE

BAG JUST WANDERED THROUGH THE ROOM. ON

THE WAY THROUGH, HE QUIETLY ABSTRACTED

ALL VALUABLES FROM THE ROOM AND FROM

YOUR POSSESSION, MUMBLING SOMETHING

ABOUT "DOING UNTO OTHERS BEFORE.."

THE TROLL'S MIGHTY BLOW DROPS YOU TO

YOUR KNEES.

THE THIEF SLOWLY APPROACHES, STRIKES

LIKE A SNAKE, AND LEAVES YOU WOUNDED.

>KILL TROLL WITH SWORD

I CAN'T SEE ANY SWORD HERE.

>KILL TROLL WITH KNIFE

A GOOD STROKE, BUT IT'S TOO SLOW, THE

TROLL DODGES.

THE TROLL'S AXE REMOVES YOUR HEAD.

IT APPEARS THAT THAT LAST BLOW WAS TOO

MUCH FOR YOU. I'M AFRAID YOU ARE DEAD.

**** YOU HAVE DIED ****

What’s happened here is that we’ve simultaneously met two of the other inhabitants of the underground, the troll and the thief. The former stays in place, but the latter is Zork‘s response to the pirate and the dwarfs of Adventure, a classic Dungeons and Dragons-style “wandering monster.” He roams throughout the underground, and not only takes the occasional poke at us with his stiletto, but — worse — picks up items we might have left here or there for safekeeping and scatters them randomly about. Even worse, he takes treasures for himself, hiding them away (more on that later). And worst of all, he’s happy to steal things off our own person. Woe to the adventurer whom he leaves in the dark without a lamp! In this case, he steals our sword just as we kind of need it to fight him and the troll and all, leaving us with only the much less effective knife. The end result is predictable.

The credit (or blame) for the combat engine belongs to Lebling:

Dave, an old Dungeons and Dragons player, didn’t like the completely predictable ways of killing creatures off. In the original game, for example, one killed a troll by throwing a knife at him; he would catch the knife and gleefully eat it (like anything else you threw at him), but hemorrhage as a result. Dave added basically the full complexity of DD-style fighting, with different strengths for different weapons, wounds, unconsciousness, and death. Each creature had its own set of messages, so a fight with the thief (who uses a stiletto) would be very different from a fight with the troll and his axe.

The danger of all this dynamism and emergent behavior is that it can lead to exactly the sort of thing that just happened to us, where the player is killed capriciously, without ever really having a chance. Eamon players never seemed to mind that sort of thing, but it didn’t sit well with Infocom. They would back well away from randomized combat in later games, a bias that the modern interactive fiction community has generally taken to heart. The main sign of this road not taken in the later Infocom canon is the “DIAGNOSE” verb, introduced in Zork to give the player a quick rundown of her current wounds, which persisted in later games as a rather pointless oddity generally yielding a generic response. Notably, “DIAGNOSE” is the only standard verb of the Infocom system that was not adapted by more modern IF languages like Inform and TADS.

Anyway, we restore a time or two, get a bit more lucky with our die rolls, kill the troll and avoid the thief, and move on into the reservoir area and, eventually, Flood Control Dam #3, one of the more memorable Zork landmarks. The relatively sober descriptions of the grand, long abandoned edifice itself are contrasted with the silliness of the guidebook we find inside the lobby.

>EXAMINE GUIDEBOOK

"FLOOD CONTROL DAM #3

FCD#3 WAS CONSTRUCTED IN YEAR 783 OF

THE GREAT UNDERGROUND EMPIRE TO HARNESS

THE MIGHTY FRIGID RIVER. THIS WORK WAS

SUPPORTED BY A GRANT OF 37 MILLION

ZORKMIDS FROM YOUR OMNIPOTENT LOCAL

TYRANT LORD DIMWIT FLATHEAD THE

EXCESSIVE. THIS IMPRESSIVE STRUCTURE IS

COMPOSED OF 370,000 CUBIC FEET OF

CONCRETE, IS 256 FEET TALL AT THE

CENTER, AND 193 FEET WIDE AT THE TOP.

THE LAKE CREATED BEHIND THE DAM HAS A

VOLUME OF 1.7 BILLION CUBIC FEET, AN

AREA OF 12 MILLION SQUARE FEET, AND A

SHORE LINE OF 36 THOUSAND FEET.

WE WILL NOW POINT OUT SOME OF THE MORE

INTERESTING FEATURES OF FCD#3 AS WE

CONDUCT YOU ON A GUIDED TOUR OF THE

FACILITIES:

1) YOU START YOUR TOUR HERE IN

THE DAM LOBBY. YOU WILL NOTICE ON

YOUR RIGHT THAT .........

Much of Zork‘s literary character, which comes through quite distinctly despite the relatively limited number of actual words in the game (it’s mostly been the very longest descriptions that I’ve been quoting here), arises from this juxtaposition of melancholic, faded glory and unabashed silliness. I’ll let you decide whether that was a real aesthetic choice or the accidental result of having too many cooks (writers) in the kitchen. In any case, we find another prime example of said silliness in the dam’s maintenance room.

>N

MAINTENANCE ROOM

THIS IS WHAT APPEARS TO HAVE BEEN THE

MAINTENANCE ROOM FOR FLOOD CONTROL DAM

#3. APPARENTLY, THIS ROOM HAS BEEN

RANSACKED RECENTLY, FOR MOST OF THE

VALUABLE EQUIPMENT IS GONE. ON THE WALL

IN FRONT OF YOU IS A GROUP OF BUTTONS,

WHICH ARE LABELLED IN EBCDIC. HOWEVER,

THEY ARE OF DIFFERENT COLORS: BLUE,

YELLOW, BROWN, AND RED. THE DOORS TO

THIS ROOM ARE IN THE WEST AND SOUTH

ENDS.

THERE IS A GROUP OF TOOL CHESTS HERE.

THERE IS A WRENCH HERE.

THERE IS AN OBJECT WHICH LOOKS LIKE A

TUBE OF TOOTHPASTE HERE.

THERE IS A SCREWDRIVER HERE.

The “EBCDIC” reference is a bit of hacker humor that might, depending on your background, require some explanation. During the early 1960s most computer makers agreed on something called ASCII (“American Standard Code for Information Interchange”) as a system for encoding textual characters on computers. Since computers can ultimately understand only numbers, ASCII is essentially a look-up table that the computer can use to know that when it encounters, say, the number 65 in a text file, it should print the character “A” to the screen. A standard was necessary to ensure that computers of different makes and models could easily exchange textual information amongst themselves. Just as everyone had settled on ASCII and thus solved a rather vexing problem, however, IBM suddenly chose to abandon the standard on its mainframes in favor of something called EBCDIC (“Extended Binary-Coded Decimal Interchange Code”). Its reason for doing so, at least according to DEC hackers, was a deliberate effort to make its machines incapable of exchanging data with those from other manufacturers, in the belief that doing so would lock its customers into using only IBM products for absolutely everything. To make things worse, EBCDIC was just a bad system in comparison to ASCII. In ASCII “A” numerically precedes “B” which precedes “C,” etc.; in EBCDIC each letter is assigned a number willy-nilly, with no apparent rhyme or reason. This makes, say, looping through the alphabet, a scenario that comes up quite often in programming, much more difficult than it ought to be. And then there was IBM’s habit of constantly revising EBCDIC, making it even incompatible with itself in its various versions. Still, it persists even today on the big legacy mainframes. Among hackers, EBCDIC came to stand in for any incomprehensible bit of language or jibberish, the hacker equivalent of saying (with apologies to anyone who actually speaks Greek), “It’s Greek to me!” And that, to make a long explanation not much longer, is the reason that the dam’s buttons are labelled in EBCDIC.

We solve a clever puzzle at the dam to adjust the water level on its two sides, thus opening up the river and the northern part of the underground for exploration. Before we do that, though, we’ll have a look at the temple to the southeast. We find there an ivory torch that, in addition to being a treasure, functions as an inexhaustable light source. This bit of mercy is even more appreciated than the extra batteries we can find in Adventure, particularly since using it doesn’t cost us points. We just need to be sure we conserve enough lantern-life to get us through the coal mine, about which more in a moment.

The sceptre, a treasure we find under the temple in the “EGYPTIAN ROOM,” is at the heart of the first really bad puzzle of the game. We are expected to take it to the rainbow outside and wave it to cross and reveal the inevitable pot of gold.

>WAVE SCEPTRE

SUDDENLY, THE RAINBOW APPEARS TO BECOME

SOLID AND, I VENTURE, WALKABLE (I THINK

THE GIVEAWAY WAS THE STAIRS AND

BANNISTER).

>E

ON THE RAINBOW

YOU ARE ON TOP OF A RAINBOW (I BET YOU

NEVER THOUGHT YOU WOULD WALK ON A

RAINBOW), WITH A MAGNIFICENT VIEW OF THE

FALLS. THE RAINBOW TRAVELS EAST-WEST

HERE.

If you’ve played a few adventure games, of course, you fully expected to walk on that rainbow. The question is how you’re supposed to arrive at this particular way of doing it. The one real hint is external to the game: Adventure featured a rod that it was possible to wave to cross a similar (albeit rainbow-less) chasm. Thus we have yet another point where Zork simply seems to assume previous knowledge of Adventure — although even given that knowledge solving this puzzle requires quite an intuitive leap.

After exploring the region beyond the rainbow, we return underground and eventually wind up in… Hades.

>D

ENTRANCE TO HADES

YOU ARE OUTSIDE A LARGE GATEWAY, ON

WHICH IS INSCRIBED

"ABANDON EVERY HOPE, ALL YE WHO

ENTER HERE."

THE GATE IS OPEN; THROUGH IT YOU CAN SEE

A DESOLATION, WITH A PILE OF MANGLED

BODIES IN ONE CORNER. THOUSANDS OF

VOICES, LAMENTING SOME HIDEOUS FATE, CAN

BE HEARD.

THE WAY THROUGH THE GATE IS BARRED BY

EVIL SPIRITS, WHO JEER AT YOUR ATTEMPTS

TO PASS.

Some of the everything-but-the-kitchen-sink feel that characterized the original PDP-10 Zork also comes through here. For all of the original mythology found in Lord Dimwit Flathead, zorkmids, and Flood Control Dam #3, we’ve also got here Hades from Greek mythology with a Dante paraphrase to boot. (Indeed, this feels more like the Christian Hell than the mythological Hades; its chilling tone provides yet another contrast to the more jokey sections.) Soon enough, we’ll also be meeting a nineteenth-century American coal mine and an Odysseus-fearing cyclops. And we’ve already visited (and plundered) the tomb of Ramses II. There’s of course a puzzle to be solved in this Hades as well, but I’ll leave that one to you. Afterward, we’ll return to the vicinity of the dam for a trip down the river.

The Frigid River section was the work of Marc Blank, who added it quite early in Zork‘s development. Its key component is the inflatable boat that we must use to navigate it. This implementation of a vehicle arguably marked the first point where Zork‘s makers really showed their willingness to go beyond their inspiration of Adventure by modeling a much more intricate, believable storyworld. It also brought with it some harsh lessons in design. Tim Anderson:

In the original game, there were rooms, objects, and a player; the player always existed in some room. Vehicles were objects that became, in effect, mobile rooms. This required changes in the (always delicate) interactions among verbs, objects, and rooms (we had to have some way of making “walk” do something reasonable when the player was in the boat). In addition, ever-resourceful Zorkers tried to use the boat anywhere they thought they could. The code for the boat itself was not designed to function outside the river section, but nothing kept the player from carrying the deflated boat to the reservoir and trying to sail across. Eventually the boat was allowed in the reservoir, but the general problem always remained: anything that changes the world you’re modelling changes practically everything in the world you’re modelling.

Although Zork was only a month old, it could already surprise its authors. The boat, due to the details of its implementation, turned into a “bag of holding”: players could put practically anything into it and carry it around, even if the weight of the contents far exceeded what a player was allowed to carry. The boat was two separate objects: the “inflated boat” object contained the objects, but the player carried the “deflated boat” object around. We knew nothing about this: someone finally reported it to us as a bug. As far as I know, the bug is still there.

I wasn’t able to reproduce this bug in this early Apple II implementation. More’s the pity; a bag of holding would be nice to have in this game. (Update: Turns out this bug is still there. I just wasn’t clever enough to figure out how to exploit it. See Nathan’s comment below for the details.)

After the Frigid River, which turns out to connect with the Aragain Falls outdoors, we next explore north beyond the reservoir. The coal mine was the result of the other Zork team members specifically asking Bruce Daniels for “a particularly nasty section.” His response originally involved a huge maze similar to the other huge Zork maze which we’ll get to in my next post. The team decided that enough was enough, however, and edited it down to a fairly manageable four rooms. Tim Anderson nevertheless notes this as “a late example of making things hard by making them tedious.” Still, the coal mine we’re left with actually isn’t all that “nasty.” It has some tricky but manageable puzzles, as long as we aren’t stupid enough to carry an open flame — i.e., the torch — inside. One of the outcomes is a diamond. (In another choice Get Lamp interview, David Welbourn notes how every adventure-game coal mine always seems to contain a diamond; would that it were the same in real life.)

Discounting only the maze area to the west, we’ve now completely explored the underground and solved all of its puzzles but one. We still have the “LOUD ROOM” to deal with.

>D

LOUD ROOM

THIS IS A LARGE ROOM WITH A CEILING

WHICH CANNOT BE DETECTED FROM THE

GROUND. THERE IS A NARROW PASSAGE FROM

EAST TO WEST AND A STONE STAIRWAY

LEADING UPWARD. THE ROOM IS DEAFENINGLY

LOUD WITH AN UNDETERMINED RUSHING SOUND.

THE SOUND SEEMS TO REVERBERATE FROM ALL

OF THE WALLS, MAKING IT DIFFICULT EVEN

TO THINK.

ON THE GROUND IS A LARGE PLATINUM BAR.

>GET BAR

BAR BAR ...

>BAR BAR

BAR BAR ...

>GET BAR BAR

BAR BAR ...

>L

L L ...

>LOOK

LOOK LOOK ...

This room feels like something of a throwback to more primitive games whose two-word parsers and limited world models forced them to replace relatively sophisticated environmental puzzles with guess-the-word games. The Zork team had specifically wanted to avoid the pitfalls of the early parsers with their frustrating non-specificity. Blank, speaking of Adventure: “It really bothered us that if you said ‘Take bird’ it would put the bird in the cage for you–sort of doing things behind your back.” All of which makes this puzzle and its solution — “ECHO” — feel like the betrayal of an ideal of sorts.

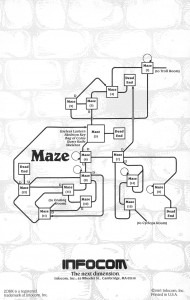

But its frustrations are nothing compared to the maze, one of the largest and nastiest of its type in adventure-game history. We’ll tackle that monster, and finish up, next time.