It’s 1980, and we just bought The Wizard and the Princess. Shall we play?

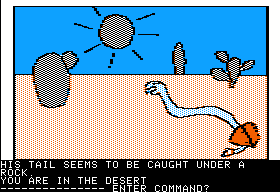

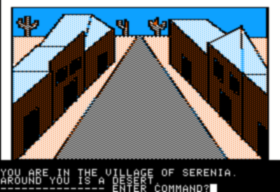

After the game boots, we find ourselves in the village of Serenia. We are about to set off to rescue Princess Priscilla from the “great and dreadful wizard” Harlin. And so we stride boldly forth, armed with wits and bravery, ready to conquer… the tedious 15-room desert maze that begins immediately outside of town. An hour or so of careful mapping later, we have determined that our path out of this monstrosity is blocked by a snake that refuses to let us pass. Naturally, being the destructive adventuring type that we are, we start casting about for some way to kill it. Perhaps one of those rocks that are scattered throughout the maze. So we try to gather one up… only to be killed by the scorpion that lurks underneath. After trying every nonsensical thing we can think of, we finally call up old Ken and Roberta themselves for a hint, whereupon we learn that we were on the right track to start with. It’s just that there is only one rock in the maze that doesn’t shelter a scorpion, and that we can therefore pick up without getting killed. Since there is absolutely no way to identify this rock, we get to spend the next hour dying and restarting until we find the right one. If we’re not so excited about watching those pretty but monotonously similar desert pictures draw themselves in slowly again and again by this point, perhaps that’s understandable.

In 1993, when the modern interactive-fiction community that still persists today was just getting off the ground, Graham Nelson wrote up a “Player’s Bill of Rights” to begin to codify good adventure-game design practice. Just in its first few turns of play The Wizard and the Princess has managed to violate 4 of 17 rights: “Not to be killed without warning”; “To be able to win without experience of past lives”; “Not to need to do boring things for the sake of it”; and “Not to be given too many red herrings.” In light of that achievement, I started wondering how many in total the game could manage to trample over. Let’s see how we go…

Not to need to do unlikely things. Not long after bashing one snake with a rock, we encounter another pinned beneath a rock (snakes and rocks obviously figure prominently in this stage of the game). This new snake is presumably as dangerous as the last, and judging from our handling of the first one we aren’t exactly fond of our scaled cousins — but that doesn’t stop us from kindly freeing the snake from his predicament. Turns out he was king of the snakes, and even has a magic word to give us in thanks! (What I’d like to know is just what sort of reptilian royalty manages to get itself stuck under a rock in the first place. Are the snake proletariat classes in revolt?)

Not to depend much on luck. Our encounter with the kindly snake was an anomaly. Pretty soon there’s another chasing us around wanting to kill us. We have to find a stick in another location in the desert, then hit the snake on the head with it to drive it away (an image I find strangely hilarious). If the snake should (randomly) appear at the wrong place or the wrong moment, though, we won’t have time to do that — and it’s curtains for us through no fault of our own.

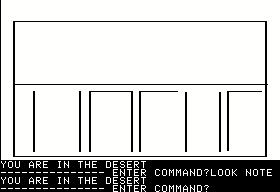

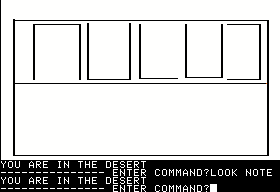

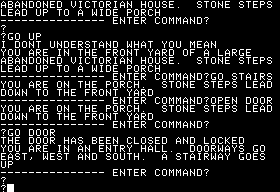

To have a decent parser. Further on in this endless desert, we discover a couple of notes just lying about, as is common in deserts everywhere. Both are known simply as “note”; the parser apparently randomly selects one when we try to interact with a “note” while both are in our current location. The only way to consistently work with one or the other is to keep each in a separate location entirely. Stuff like this makes me want to write this right in all capital letters, like this: TO HAVE A DECENT PARSER, DAMN IT!

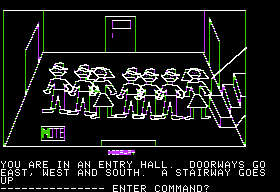

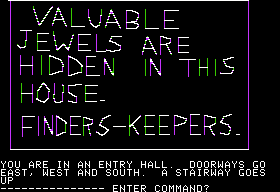

Not to be given horribly unclear hints. Yet further on in the desert we come to a deep, uncrossable chasm. We have to enter the magic word “HOCUS,” whereupon a bridge materializes. I’m not exactly sure how the player is expected to divine this word, but my best guess is that one is supposed to somehow extract it from the contents of one or both of those notes I just told you about, and which are shown above. The one on the left kind of looks like “HOCUS,” doesn’t it? Maybe, if you squint just right? Of course, even if we make that intuitive leap we still have to go around typing “HOCUS” literally everywhere, until something finally happens. But by now the game has already pretty thoroughly ground our right to be exempt from “boring things” into dust with its best jackbooted thugs, hasn’t it?

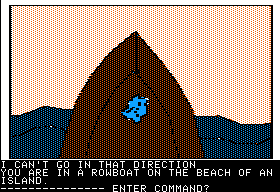

To have a good reason why something is impossible. We escape the mainland to a small island via a rowboat we find handily lying about. Having dealt with the usual inanities there, there comes a time when we are ready to leave. It might seem natural to use the rowboat that brought us there to travel onward, but that’s impossible. Why? I don’t know — the game just tells us, “I can’t go in that direction.”

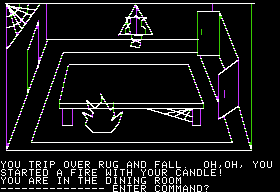

To be allowed reasonable synonyms. We are actually expected to travel on using a potion of flight. (We can only figure out exactly where on the island to use it by drinking it over and over again, once in every room, restoring after each experiment. But by now a sort of Stockholm-Syndrome-esque complicity has set in, and we just accept that and go to work with a sigh.) The perfectly natural noun “potion” is not accepted here. We can only “DRINK VIAL” (an interesting thought…) or “DRINK LIQUID.”

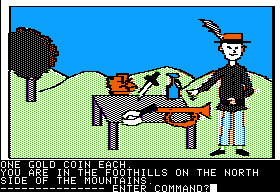

To be able to win without knowledge of future events. Moving on, we encounter a peddler offering what appear to be a pair of boots, a dagger, a wine jug, a magnifying glass, and a trumpet for sale. We have just one gold coin, and no idea which of these items we’re likely to need. So we have to save the game and start buying them one by one, each time moving on into the game looking for a puzzle we can solve with that item or the dead end that indicates we must have chosen wrong. And no, the peddler doesn’t have a trade-in policy.

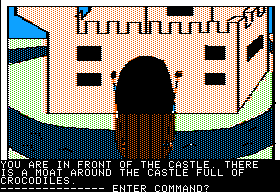

To be able to understand a problem once it is solved. At long last we come to the wizard’s castle. We’re confronted there by a closed drawbridge. It turns out that the correct solution to this problem is to blow the trumpet we bought from the peddler — there’s that question answered, anyway. I recognize some allusion to a returning knight blowing his horn to alert the castle of his return. But why should this work for us, the wizard’s enemy? Shouldn’t blowing the trumpet rather bring a fireball down on our head? And who opens the drawbridge? Certainly no doorman greets us inside. Or is it a magic trumpet? But if it’s a magic trumpet that gives one access to his stronghold, why the hell did the wizard give it to the peddler? Or did he lose it, and the peddler just sort of found it by the roadside? The world will never know…

Inside the castle, our showdown with the wizard is one of the most anticlimactic finales ever. In lieu of the wizard himself, Roberta presents us with yet another enormous, empty maze. (At least the game, in ending as it began, manages a sort of structural unity.) We never even see him as a wizard, only as a bird he has for some reason chosen to transform himself into. Luckily we have a magic ring that briefly turns us into a cat — if we mess around with it long enough to figure out we need to rub it, not wear it, that is — and that’s that.

And Nelson’s other player’s rights? “Not to have the game closed off without warning,” “Not to have to type exactly the right verb,” and “To know how the game is getting on” are violated so thoroughly and consistently by the game that there isn’t much point in belaboring them.

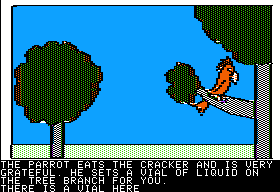

Not to need to be American to understand hints. This right was born from Nelson’s loathing for one particular puzzle, the infamous baseball diamond of Infocom’s Zork II (about which more when we get there); hence its unusual specificity. I think it can be better reframed as a prohibition against requiring too much culturally specific knowledge of any stripe. The Wizard and the Princess manages to not offend too deeply here, although there is one point where, having escaped from the mainland to a tropical island via a rowboat we found handily lying about, we have to give the cracker we found in the desert (amazing what turns up in the desert, isn’t it?) to a parrot. While not exclusively American, I believe the old “Polly want a cracker” meme is confined to the English-speaking world.

To be given reasonable freedom of action. Within the boundaries of the primitive parser and world model, the player does have reasonable freedom. It’s mostly freedom to hang himself, but still… freedom isn’t free, or something like that.

Without these last two, then, we are left with a solid 15 out of 17 potential violations. Not quite a perfect run, but a damn good effort.

So, having had my bit of fun, it’s time to say a few things. Some might regard it as a poor sport to so thoroughly rip apart one particular offender in an early adventure-game scene that was absolutely full of them. Roberta was after all, like other early designers, working without a net, with no received wisdom about good design practice, and with extremely primitive technology to boot. It’s a valid enough charge. The only defense I can offer, which is not really a defense at all, is that I feel particularly unforgiving toward Roberta because she just kept on doing this sort of stuff throughout her almost 20-year career, long after excuses about received design wisdom and technology ceased to hold water. And, having spent so much time with old-school adventures over the past six months, perhaps there did come a point where I just had to vent. Certainly this has been a complete violation of one of my normal policies for this blog, to always try to see the works I analyze in the context of their times. Maybe it’s a good idea to get back to that now, and to ask just why players accepted this stuff — to most outward appearances happily — in 1980, as well as what led designers to commit such violence against their players in the first place.

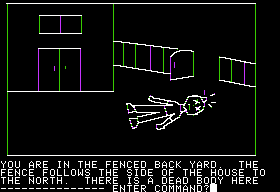

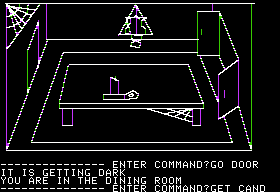

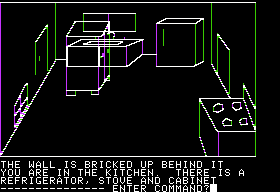

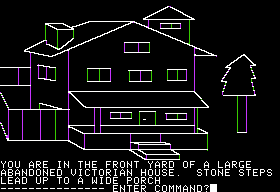

The Wizard and the Princess is even today not totally without appeal. There is something attractive about its fairy-tale whimsy and its sprawling, discordant map. Discounting only ports of the original Adventure, The Wizard and the Princess was easily the largest adventure game yet to appear on a home computer. And then there are of course those pictures, the real heart of the game’s contemporary appeal. Quaintly appealing today, they were a technical tour de force in 1980, a reason to call family, friends, and neighbors over to the little Apple in the corner to just marvel. Owners of early home computers had had precious little immediately impressive to show off on their machines, just lots of blocky monochrome text showing the strangled English of Scott Adams or cryptic numbers and programming statements. Now they had something impressive indeed. Just as every generation considers its music to be rife with timeless classics and the music of the following generations to be worthless trash, every generation of gamers loves to accuse those who follow of being interested only in flashy graphics and sound. Well, guess what… every generation of gamers has always been interested in flashy graphics and sound. It’s just that this one had precious little of it available to them. If they had to find it in a game that has come to seem almost a caricature of obstinate old-school text adventures, so be it.

That said, there were gamers who reveled in the difficulty of games like The Wizard and the Princess. Some not only accepted balky two-word parsers but considered them part of the fun. In their view, solving a puzzle was a two-step process: figuring out the solution, and figuring out how to tell the computer about it. There was often an odd sort of machismo swirling around in these circles, as gamers who complained about obtuse gameplay were labelled as “not real adventurers.” To what extent this hardcore was rationalizing as a way of accepting the games they were stuck with anyway and to what extent they really, honestly liked guessing the verb and trying literally everything everywhere I’ll leave to you to decide. So much of gaming in this era was still in an aspirational phase, asking players to imagine that the primitive bundle of frustrations they were playing then was already the immersive interactive story everyone could see out there on the horizon, somewhere off in the future. Perhaps that begins to explain the curious sanguinity of everyone during the adventure game’s heyday, manifested in the refusal — still present in the nostalgic even today — to ever cry foul. But then the computer press was not terribly critical of any software, being bound up with the publishers as they were in a web of mutual self-interest. I know that as a kid who loved adventure games — or at least the idea of them — during the 1980s, I was frequently infuriated by the reality. I don’t think I was alone.

And the designers? Much of what led to designs like The Wizard and the Princess — the lack of understood “best practices” for game design, primitive technology, the simple inexperience of the designers themselves — I’ve already mentioned here and elsewhere. Certainly, as I’ve particularly harped, it was difficult with a Scott Adams- or Hi-Res-Adventures-level parser and world model to find a ground for challenging puzzles that were not unfair; the leap from trivial to impossible being made in one seemingly innocuous hop, as it were. However, some other pressures might not be immediately obvious. Consider that Ken and Roberta sold The Wizard and the Princess for $32.95. For that price, they needed to reward gamers with a good few hours of play. Yet there was a sharp limit to the amount of content they could deliver on a single floppy disk and a 48 K computer. (The Wizard and the Princess may have been an unusually big game by 1980 standards, but you can still easily get through it with a walkthrough in a half hour — and most of that time is spent waiting on pictures to load and draw themselves.) The obvious solution was to make the game hard, so gamers would be forced to spend literally hours scrabbling after each tiny chunk of actual content. Later, as piracy became more and more of a problem, some designers perhaps began to see almost unsolvable puzzles as a solution of sorts, for that way they could still get the pirates to buy hint books. Sierra itself stated repeatedly in the later 1980s that its hint-book sales often exceeded the sales of their associated games. What it neglected to mention, unsurprisingly, was the obvious incentive to produce unfair games this created, to earn some money even from the pirates and increase profits overall.

The real danger of bad design practice, whether born of laziness, greed, or simple rigidity (“that’s just the way adventure games are”), is that players get tired of being abused and move on. And if other genres begin to offer compelling, even story-rich experiences of their own, that danger becomes mortal. Through the 1980s designers had a captive audience of players entranced enough by the ideal of the adventure game and the technology used to bring it off that they were willing to accept a lot of abuse. When that began to change… But now we’re getting way, way ahead of ourselves.

For now, suffice to say that, whatever its failings, The Wizard and the Princess became an even bigger hit than Mystery House had been. Softalk magazine’s sales chart for that September already shows it the second biggest selling piece of software in the Apple II market, behind only the business juggernaut VisiCalc. It remained a fixture in the top ten for the next year, eventually selling over 60,000 copies and dwarfing the sales (10,000 copies) of Mystery House. By the end of the year, Ken and Roberta had a number of other products on the market under the On-Line Systems label, and had rented their first office space near their new home in Coarsegold. The long suffering John Williams gave up his promising career as the world’s first software distributor rep to become On-Line Systems Employee #1, where his annual salary amounted to about what he had been earning in a month with the distribution operation. In a very real way, The Wizard and the Princess made the company that would soon go on to worldwide success as Sierra Online.

If you’d like to try The Wizard and the Princess yourself, I have a disk image here that you can load into your emulator of choice. We’ll be leaving On-Line Systems for a while now, but we’ll drop in on them again down the line, at which time I promise to try not to treat their other works quite so harshly.

Next up: another group of old friends we met in an earlier post.