Ken Williams got the online religion early or late, depending on how you look at it. Despite running a company whose official name was Sierra On-Line — admittedly, the second part of the name was already being de-emphasized by the end of the 1980s, and would eventually be dropped entirely — he had paid no more attention than most of his peers to the rise of commercial online services like CompuServe. Sierra maintained a modest presence in such places, even agreed to the occasional online chat, but telecommunication was hardly central to their business strategy during the first eight years or so of their existence. All that began to change, however, when a new service called Prodigy made a splashy entrance in 1988.

Almost a decade after CompuServe’s consumer service had been born, Prodigy breezily declared themselves to be the “first consumer online service,” full stop. In so doing, they demonstrated a certain chutzpah in which they would never be lacking, and which would decidedly fail to endear them to most others in their industry. Yet underneath the bluster there was perhaps an honest aspirational vision. Backed by the unlikely partners of Sears and IBM, Prodigy desired to be, to coin a phrase, the online service for the rest of us. They became the first service after the Commodore 64-only QuantumLink to allow access only through a graphical front-end which they themselves provided to their customers. There would be no scrolling green text for their subscribers, but rather attractive screen layouts full of color and even pictures. Preferring to see themselves as the next step in traditional, top-down mass media — the natural successor or at least adjunct to newspapers, magazines, and television — they hewed to this philosophy to the complete exclusion of the user-driven initiatives that had done so much to build the other online services: things like chat, file libraries, and self-organizing communities of interest. (Incredibly, online chat, the killer app that had first gone up on CompuServe in the Dark Ages of 1980, wouldn’t arrive on Prodigy until 1994.)

In compensation, Prodigy planned to offer more content from Big Media than had ever been seen online before, alongside enough online shopping to make any brick-and-mortar mall stroller green with envy. Indeed, it was typical mall shoppers rather than typical computer hobbyists that they were really trying to reach. Rather than hosting chats with the likes of computer-game developers and NASA engineers, they curated question-and-answer forums with such mainstream celebrities as the fitness diva Jane Fonda and the famed sportscaster Howard Cosell. Further, they offered all of this at a flat rate, a first for the industry. The monthly subscription price of $10 — a price which would only buy you about two hours at best on any of the other services — was augmented by online advertising that took full advantage of the graphical front end. In this area as well, then, Prodigy became a pioneer, albeit of a perhaps more dubious stripe.

Prodigy went live on April 11, 1988. From the moment he first logged on later that year, Ken Williams was excited by what he saw there in a way he had never been by CompuServe or any of the other text-based services. He called Prodigy “a preview of the future” in his “President’s Corner” of Sierra’s corporate magazine.

I boot it up in the morning, and I’m greeted with a “front page” that gives headlines on the major news stories of the day. Beside each headline is a number to punch up the text of the feature, which is written in a professional journalistic style. After the front page, I can check the price of my company’s stock through Prodigy’s Dow Jones service. Because I’m a West Coaster and Wall Street opens before I get out of bed each morning, the stock price I see represents the price of my stock as it was within the last fifteen minutes (not what it was after closing last night).

I can also catch the up-to-date prices of other publicly-traded home-software companies or I can check to see if any of the top computer makers has made a big announcement. I also check the local weather, and occasionally the weather of a city I’m to travel to that day (Prodigy will give me a report for almost anywhere), and I always, always read the PC Industry Column by Stewart Alsop III.

If I have time during the morning (but usually at night), I’ll access one of the “interactive magazine” sections of Prodigy. Among the writers for Prodigy are Gene Siskel (of Siskel and Ebert’s At the Movies), Sylvia Porter (finances), Jane Fonda (fitness), Jolian Block (taxes), and a host of others. Each of these people contributes a column worth reading, and the columns are written when news happens, not just once a week or once a month.

It’s great to have this online magazine rack constantly available, but the best part of Prodigy is that you can write the writers. Recently I saw a Gene Siskel review of the movie Parents on Prodigy. As I enjoy such offbeat movies, and Gene appeared to have similar taste, I wrote him a quick note asking if he could recommend similar films. The next day when I booted up the service I had a short note waiting from Gene that contained the names of two other films I would like. Once, I didn’t like a Stewart Alsop column, and I got my aggressions out immediately by sending him a note of disagreement (no response from Stewart was given or expected). I consider this interactivity to be the major plus of this interactive-magazine format.

The reasons for Ken Williams’s immediate enthusiasm for Prodigy aren’t hard to divine in the context of his strategic vision for Sierra and his industry. As we saw in my last article, he was convinced that computers were simply too hard to use, and that the path to more universal acceptance of his company’s products lay in smoothing out the rough edges of being a computer gamer, in commodifying games like any other form of mass media. If this process entailed the loss of some of hacker culture’s old can-do spirit of empowered creativity, well, such was the price of progress; tellingly, and even as he rejected making games for the platform himself, Williams was a great admirer of Nintendo and their carefully-curated walled garden of cartridge-based videogames. Prodigy in the online space, like Nintendo in the console space, was moving in the direction he hoped to take Sierra in the computer-game space.

Yet the example of Prodigy was also more to Ken Williams than just an object marketing lesson from a related industry. It woke him up to the possibilities — the possibilities, that is, for Sierra themselves — in the online space. Williams, in short, wanted in on that action which he was coming to believe would do so much to shape the future not only of computers but of media in general.

In 1989, a new terminal program from an outside programmer reached Sierra by a somewhat circuitous route that wound through their close relationship with Radio Shack. They chose to revise it and publish it as one of their rare forays into application software. Sierra’s On-Line — yes, the name is a little too cute — was designed, in what was fast becoming the typical Sierra fashion, to make going online just that little bit easier for people who didn’t eat and breathe baud rates and transfer protocols. It shipped, for instance, with a script that would do all the work of getting you logged in and signed up with CompuServe for the first time for you, following up that helping hand with a guided tour of the service. (Ken Williams himself may have been most enamored with Prodigy, but that didn’t mean Sierra would ignore the only online service with more than half a million subscribers in 1989.) After that introduction, many tasks could be automated by clicking big, friendly onscreen buttons, sort of an attempt to bring the Prodigy experience to CompuServe. Previous terminal programs, ran Sierra’s marketing line, had been “too complex and intimidating for the average user to want to tackle; one look at a two- or three-inch thick manual, and most people decided they weren’t really all that interested in going online.” Sierra’s On-Line, by contrast, would make online life “available to a much wider audience than before. With a program this easy, convenient, and inexpensive, going online would be within the reach of anyone with a computer and a telephone.”

While there’s no indication that Sierra’s On-Line became a particularly big seller, much less revolutionized the online demographic in the way the company seemed to have hoped, it is illustrative of their thinking as the 1990s loomed. Ditto the “Sierra BBS” which they set up around the same time, sporting enough incoming telephone lines to let 32 people be online at once. Sierra claimed that over 35,000 people were visiting each month by the end of 1989, getting hints for the games and downloading demos, patches, and curiosities like a “3-D Animated Christmas Card” and a standalone version of “Astro Chicken,” an action game embedded in Space Quest III. And at the same time, Sierra became a great booster of Prodigy. In addition to setting up a big presence on the new service proper, they took to dropping signup kits directly into their game boxes, thus getting them into the hands of hundreds of thousands of gamers.

In a 1990 address, Steve Jobs, a visionary who gets lots of credit for the many things he got right but little blame for the equal number of things he got wrong, said that the 1990s would be “the decade of interpersonal computing.” When he said it, he was talking of small-scale connectivity via LANs, not the wide-scale connectivity that was already being enabled by services like CompuServe and Prodigy, much less the epoch-making invention that would be the World Wide Web. Ken Williams responded, rightly, that Jobs was “thinking too small. I agree that ‘interpersonal computing’ — the idea that the individual computer owner will soon find himself acting as part of a bigger connected computer community — is the next step in the evolution of personal computing. But I disagree with Jobs’s vision of the company office as the birthplace of this technology.”

Even as Jobs was articulating his narrow vision of interpersonal computing to an industry conference, Williams had put Sierra to work attempting to forward his own, more expansive view of computing’s future in a more direct fashion than even the Prodigy relationship entailed. On October 31, 1990, Sierra quietly announced that they had begun testing a new, self-standing online service of their own, one that would go far beyond the Sierra BBS. Ken Williams, from the press release:

Sierra is interested in extending our core product-development technology to have multiplayer capabilities. Our long-term goal is to have games, similar to those we now sell, which can be played simultaneously by large groups of people over a wide-area network. We have no plans currently to announce any particular product, any timetable for roll-out, or even any sense of what form a national roll-out might take — e.g., whether we would operate our own network or offer our product through some existing network. This announcement is only made to correct misinformation that may have been leaked by our testers. Whereas we are very excited about this test, it is much too early to speculate as to whether it might lead to some marketable product. We should know more by early next year, at which time we will be able to comment further.

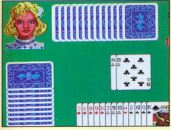

And so, with slightly under 1000 volunteer testers located in the Los Angeles area, a modest slate of classic parlor games like chess and bridge, and heaps of caveats like those above, The Sierra Network was born.

The test “yielded amazing results,” reported another press release the following May: “Many of our testers had never touched a computer before, but were suddenly averaging 20 hours per week and more on TSN.” In choosing the testers, Sierra had deliberately reached out beyond the demographic that typically played computer games, even going so far as to loan computers to those of their non-techie guinea pigs that needed them. Ken Williams had been inspired by his mother, an avid bridge player, to make that game a special priority, as he did the people of her advanced age who tended most frequently to play it — i.e., the least likely of all people to use a computer under normal circumstances.

The influence of Prodigy could be seen all over The Sierra Network, from the graphical interface that was designed to be easy enough for that much-abused least-common denominator, the proverbial grandmother, to the plan for flat-rate pricing of about $12 per month. It’s thus somewhat ironic to note that Prodigy itself was in danger of crashing in flames at the same time that The Sierra Network was getting off the ground. The former service’s membership had soared by 1991 to 600,000, but, as might have been predicted had its administrators looked more closely at the experience of CompuServe and other predecessors, a big chunk of those subscribers were proving more interested in interacting with one another than they were in engaging with the curated content Prodigy and their corporate-media partners provided. This was throwing the financial model all out of whack. Prodigy responded by censoring forum discussions, by limiting email to 30 messages per month, and by raising the subscription price to $15 per month. Some of their subscribers organized a so-called “Cooperative Defense Committee” to fight back, precipitating an internecine conflict the likes of which has never quite been seen before or since. Members of the user resistance claimed Prodigy was reading their emails, and a rumor spread, never to be conclusively proved or disproved, that Prodigy’s software was snooping through the contents of subscribers’ hard drives — thus providing the service with another dubious first as the centerpiece of the first notable spyware scandal in the history of the computer industry. Although the civil war had little obvious effect on the service’s overall subscriber count, which only continued to grow in a bullish environment for the idea of interpersonal computing in general, it cost Prodigy something less tangible but equally precious. After the great PR debacle of 1991, Prodigy would never again enjoy the prestige and influence of their first moment in the sun. Their thunder would increasingly be stolen by America Online, a service launched with much the same aspirations toward mainstream, non-computer-geek Middle America, but one which would prove to be much better managed in the long run.

So, as Sierra charged ahead with their own online service they had object lessons, should they choose to heed them, that managing such a service — especially at flat-rate pricing — was more difficult and expensive than it might first appear to be. In addition to Prodigy, they could look to PlayNet, the service which seven years before had tried to offer at discount prices to owners of Commodore 64 computers a suite of simple board and card games not all that dissimilar from those of the nascent Sierra Network, only to go bust within a few years, largely because little PlayNet had been unable to negotiate the favorable terms with the big telecommunications firms that might have made their business viable. Sierra too, while a big wheel in the computer-game industry, was next to nothing in the eyes of the telecom giants. Yet they believed they could overcome the factors that had killed PlayNet and nearly done in even Prodigy by using their basic service almost as a loss leader for premium content in the form of bigger, meatier games. Ken Williams described The Sierra Network as the cable television of online services. Sure, you could pay a fairly small flat fee and just get the basic package, but to get the online equivalent of HBO you’d have to pay a premium. The folks at Dynamix were already testing an online version of their hit World War I dogfighting simulator Red Baron, and Sierra planned to make two new “theme parks,” called SierraLand and LarryLand, available to subscribers at additional cost by 1992.

On May 6, 1991, Sierra announced that The Sierra Network was officially a go, being spun off as a wholly-owned subsidiary of the parent company. They intended to make it available to most of California at the flat rate of $12 per month by the end of the month, and to the entire country at that rate within a year. In the meantime, subscribers outside of California could gain access for $5 per month plus $2 per hour, still far cheaper than most other online services of the day.

As one might expect, though, early paying members were heavily concentrated in California. Far from being a disadvantage, this situation was in some ways just the opposite. When wildfires burned more than a thousand homes to the ground in northern California, The Sierra Network’s subscribers put together an impromptu emergency-response center to keep everyone updated on the fires’ current course. During happier times, subscribers organized pot lucks and picnics in the non-virtual world. And, inevitably, romance soon sprouted from this fertile soil of friendship; the first Sierra Network marriage proposal took place as early as August 30, 1991.

But Sierra’s ambitions for the service had of course always extended well beyond California. On June 1, 1992, they rolled out, just as they had promised, nationwide flat-rate pricing: $13 per month, with a usage cap of 30 hours per month to head off the sorts of heavy users who had so nearly been the death of Prodigy. To date, the service had been growing at a reasonable if not breathtaking pace despite going virtually un-promoted outside of Sierra’s own magazine, surpassing 25,000 subscribers in the first year. If not enough to set CompuServe, Prodigy, or America Online shaking in their boots, it still wasn’t bad for a service that offered little beyond games and socializing; even a non-gaming something as basic as email had taken months to arrive. Now, with the nationwide roll-out underway in earnest, Sierra launched the biggest advertising blitz in their history to that point, encompassing glossy print and even television. To accommodate the expected surge in subscriptions, the parent company found their online subsidiary their own space, moving them into a building that had formerly been the home of a local Oakhurst steakhouse known as The Old Barn. (The place had been a popular stop for tourists to nearby Yosemite National Park; there was a bit of a problem with trail-weary hikers turning up, marching in through the front door, and asking for a menu without ever noticing the changed signage.)

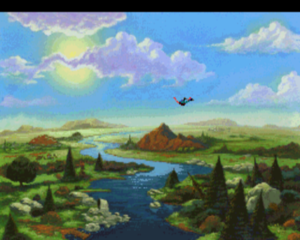

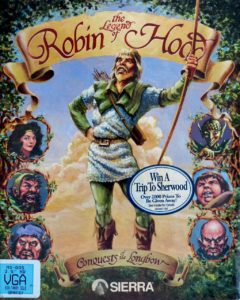

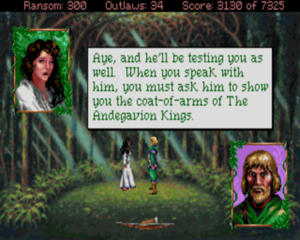

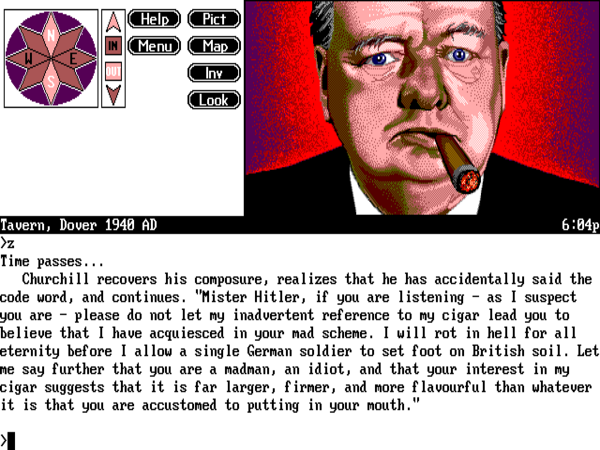

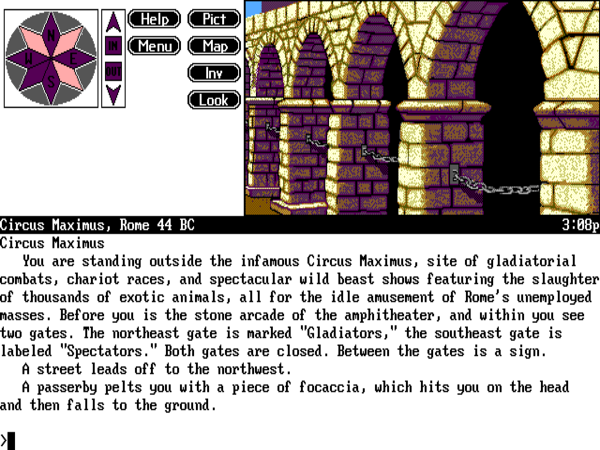

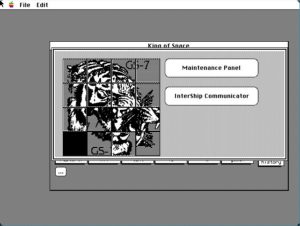

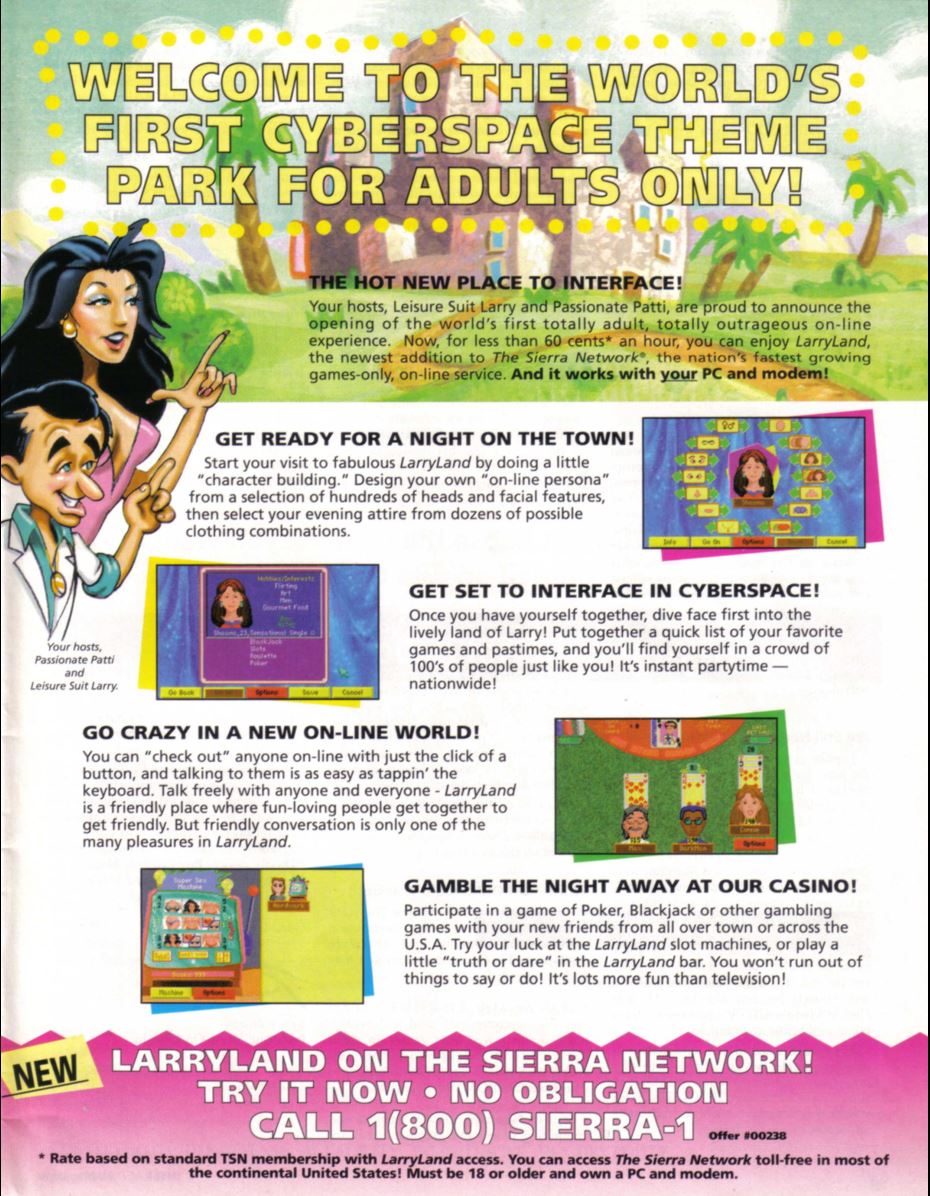

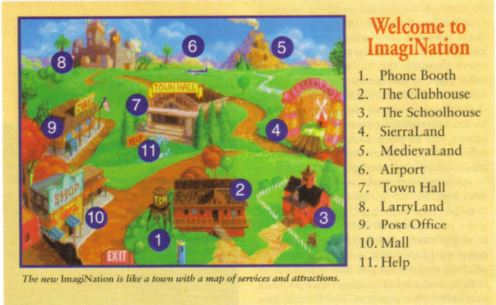

Ken Williams’s cable-television-inspired “premium packages” also started to come online — and also just as promised — during 1992. For the extra price of $4 per month per package, subscribers could access SierraLand, an online amusement park complete with white-water rafting, mini-golf, a videogame arcade, and paintball; LarryLand, an online casino, a veritable Lost Wages straight out of Leisure Suit Larry in the Land of the Lounge Lizards; and MedievaLand, whose centerpiece was The Shadow of Yserbius, a more limited but better-looking multiplayer CRPG than America Online’s Neverwinter Nights. The truly hardcore could get access to it all, plus unlimited online time, for the low, low price of $150 per month — still a bargain compared to what some people were shelling out just to chat on services like CompuServe.

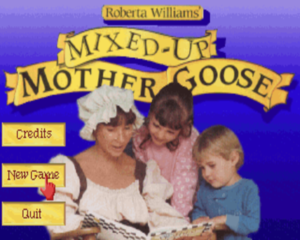

Ken Williams’s greatest business hero was Walt Disney. He particularly admired Uncle Walt’s talent for turning his cartoon characters into indelible icons of international pop culture, and strove to do the same for the stars of Sierra’s games. In the early 1990s, Larry Laffer, whose gradual transformation from the skeevy pervert of the first Leisure Suit Larry game to lovable loser was by then complete, suddenly started turning up everywhere: on tee-shirts; on coffee mugs; as an opponent in the casual-game collection Hoyle Book of Games; as the proprietor of LarryLand on The Sierra Network; even as the ersatz software mogul behind The Laffer Utilities, a collection of otherwise businesslike MS-DOS add-ons. If Larry never quite became the mainstream icon Sierra wished, you certainly can’t fault them for lack of effort.

To their credit, Sierra had understood from the beginning that the socializing that took place around the games would be at least as important as the games themselves to their subscribers; in this sense at least, they were the polar opposite of Prodigy’s benighted management. “Where people meet people to have fun,” ran The Sierra Network’s early tagline, consciously placing the “people” part before the “fun” of the games. “Playing [offline board and card] games has very little to do with gaming,” wrote Ken Williams. “An evening playing bridge with friends has more to do with the quality of your relationship with your friends than with the actual card-playing.” Sierra worked hard to recreate this chummy atmosphere in an online context.

Even as the various components of The Sierra Network might point back to PlayNet, to Neverwinter Nights, or (in the case of the online Red Baron) to GEnie’s Air Warrior, Ken Williams’s animating vision of the service made it stand out from an online marketplace of increasingly indistinguishable offerings. In the eyes of most modern gamers, the single-player plot-heavy adventure games that are still Sierra’s most famous vintage stock-in-trade might seem to exist at the opposite end of a continuum from the shorter-form grab-and-go games that made up the majority of The Sierra Network’s offerings. Yet Williams didn’t see things that way at all at the time.

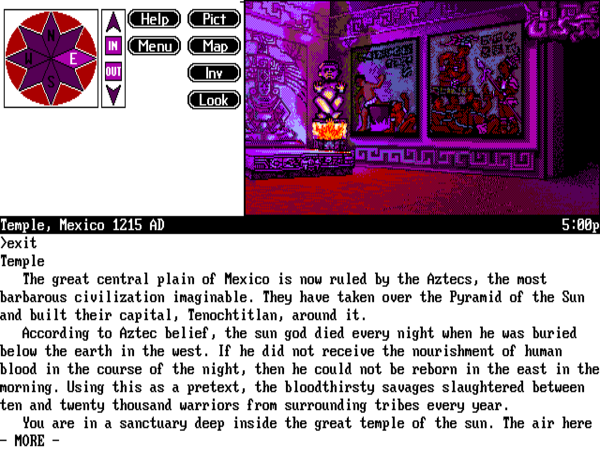

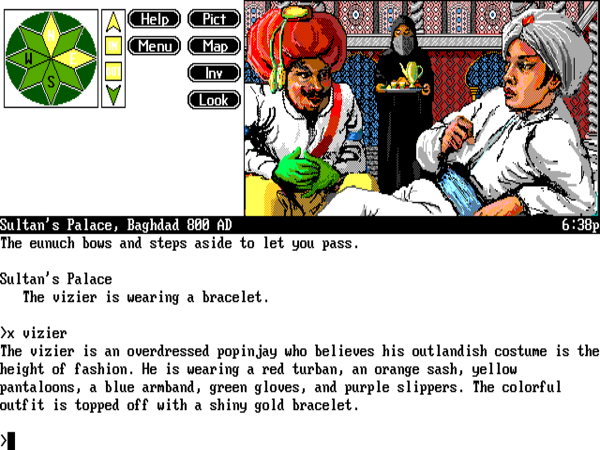

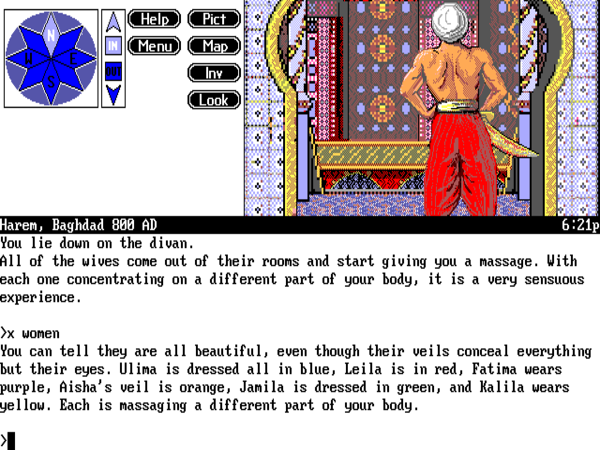

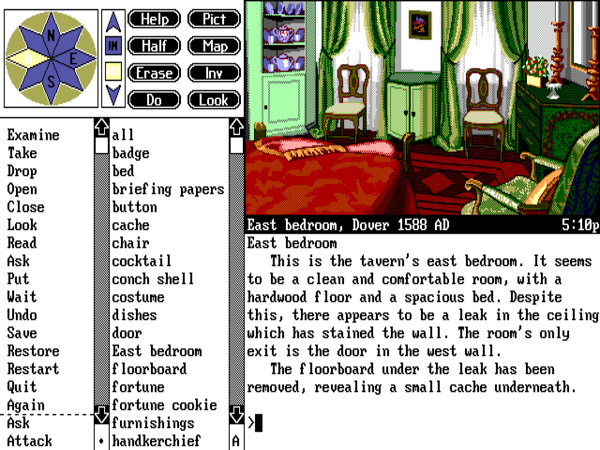

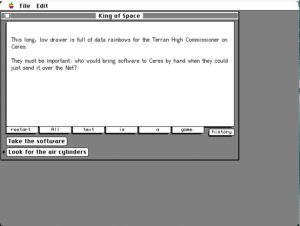

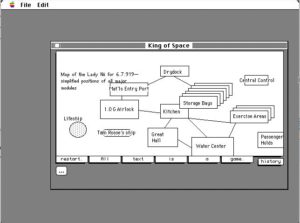

In my recent conversation with Judith Pintar, she mentioned how she came to see CompuServe as a sort of virtual space with a spatial architecture of its own, a maze of twisty little passages winding through chat rooms, discussion boards, and online games. While that may have been an idiosyncratic take on CompuServe — an outgrowth of her unique personality — it was one that Ken Williams wanted to make real for everybody on The Sierra Network. To an extent rivaled only by Habitat, the earlier but brief-lived online community Lucasfilm Games had created for QuantumLink, he strained to turn The Sierra Network into an embodied space not at all far removed from the virtual spaces inside his company’s adventure games. Just as much as Sierra’s offline adventure games, their online service was to be a form of “interactive multimedia.” The Sierra Network, Williams had long since declared, was nothing less than “my vehicle for experimenting with virtual reality.” His vision was perhaps summed-up best in a tossed-off line he offered even while the premium “theme parks” were still twinkles in their developers’ eyes: “Wouldn’t it be nice if you could play our games, but all the other characters you ran into were real people?”

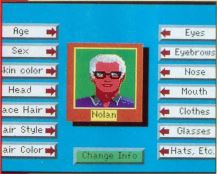

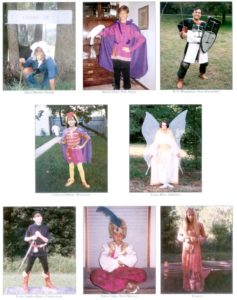

The first step a new subscriber took on the service was to make an avatar using the “FaceMaker” program, choosing an age, a sex, a race, a hair style and color, a facial expression, and more; it all added up to an almost infinite range of possibility. Some subscribers tried to construct avatars that looked pretty much like they themselves did — or at least like idealized versions of themselves — but others used The Sierra Network as an opportunity to try out entirely different identities. Such practices, which became known among the subscribers as “masquerading,” weren’t discouraged by the service’s administrators. On the contrary: a single subscriber was allowed to have multiple avatars, and plenty took advantage of that, putting on different looks, personalities, and even genders to suit their mood of any given evening. “Being us, whoever we are, is tough work,” said Jeffrey Leibowitz, The Sierra Network’s director of marketing. “It’s nice sometimes to not be you.” Marketing considered adopting as a slogan “Be all that you can’t be,” a great riff on the United States Army’s longtime slogan of “Be all that you can be,” but it was sadly rejected in the end, probably out of fear of offending delicate patriotic sensibilities.

The Sierra Network wasn’t a collection of services that you used; it was rather a geography of places that you visited.

The sense of embodied physicality was perhaps the key thing that made The Sierra Network so precious to the many — and there are a surprising number of them — who remember it with such nostalgic fondness today. The terminology of a cyber-space is all over Sierra’s own way of talking about the service — sometimes, one senses, for calculated reasons, but other times for unconscious reasons, simply because that terminology seemed the best to use to describe an experience of this nature. So, you didn’t sign into SierraLand or LarryLand, you went there. And once there, you didn’t enter commands or even click buttons; you strolled the midway of the amusement park or the aisles of the casino, looking for something — or someone — that caught your interest. Even the simplest games on The Sierra Network were constructed with this eye toward embodied virtual space; when you played bridge, you saw the table along with your partner and your opponents sitting across it, just as if you were really there. What if online life writ large had eschewed the metaphors of print from the beginning for embodied virtual reality? The Sierra Network takes us as close as we’re likely to get to answering that counter-factual.

By 1992, a real buzz was growing up around online services in general. America Online had an IPO that spring which exceeded all expectations, attracting committed backing from such influential patrons as Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen. Ross Perot, an independent candidate for President of the United States who would manage to attract 18.9 percent of the vote that November, was making news with his proposals for an “electronic town hall,” where citizens across the nation could come together to discuss the issues of the day with the politicians who served them.

The Sierra Network fit right into this zeitgeist, attracting considerable mainstream attention of its own. Noted tech pundit John Dvorak called it nothing less than “the future of telecommunications.” The Washington Post‘s business section wrote about it using words that might have been cribbed directly from Sierra’s own press releases: “If TSN takes off, it could define a new medium — the merger of computer games and online information services into a form of entertainment never seen before. TSN could ultimately propel Sierra into the big leagues, pushing the company far beyond its current annual sales of about $50 million.” Alan Truscott, arguably the world’s foremost authority on the game of bridge, promoted The Sierra Network’s online version of his favorite pastime via his New York Times column on same: “Playing on Sierra is less impersonal than it sounds. From a list of those available, designated by first names or code names, you invite three others to play. Each player designs a face that may or may not be an accurate portrait of themselves, which shows on your computer screen. It is easy to discuss bidding methods, conduct a postmortem, or simply chat.” “It would be wrong to suppose,” he concluded, “that playing bridge in one’s home while linked by computer and telephone to three other players must be an unsocial activity.”

By some metrics, then, The Sierra Network was doing quite well. Doubtless thanks not least to all this positive press, total subscription revenues jumped from a paltry $266,000 in the first year all the way to $2.825 million in the second. And yet one stubborn fact couldn’t be disguised by all the good news: Ken Williams’s pet online service just wasn’t making Sierra any money. In fact, it was costing them a bundle. Unusually for this company that saw themselves as a maker of “premium” products with premium prices to match, Sierra had priced their service far too aggressively to ever turn a profit even with the optional packages. They had misjudged the cost of maintaining the computing and networking infrastructure to run the service, misjudged the speed at which telecommunications costs in general would decrease, and misjudged their ability to negotiate with the telecom giants as a paltry $50-million-a-year company.

Nor was the news unadulteratedly positive even on the demand side. By the spring of 1993, Sierra Network membership was showing ominous signs of having already plateaued, or even of having started going in the other direction. Many of the most basic aspects of running an online service — things that companies like CompuServe had been doing for years with apparent ease — were a huge struggle for Sierra. Their service crashed with disconcerting regularity, and they could never seem to catch up to customers’ demands on their bandwidth; trying to connect to The Sierra Network for a casual game of backgammon could often be, as Sierra’s marketing director John Williams put it, like trying to get through to Microsoft’s customer support right after the release of a new version of MS-DOS. In addition to spotty reliability and connectivity, another big problem the service faced in trying to further build its membership rolls was the very fact that it was so exclusively games-focused. The typical pattern on CompuServe or America Online was for customers to sign up with plenty of sober, practical reasons in mind or at least on the tongue — online news, online stock-market quotes, etc. — and then get inadvertently hooked on chat and games. The Sierra Network couldn’t pull the same bait and switch, for the simple reason that it lacked the same bait. To sign up for The Sierra Network, you had to be willing to say up-front that this was strictly an entertainment expense — strictly an indulgence, if you will. For some reason, many potential subscribers — even the ones with gigantic cable-television bills — seemed to find that a hard admission to make.

In the fiscal year ending March 31, 1993, Sierra as a whole turned the wrong kind of corner after years of steady profitability, posting an ugly loss of $12.3 million. While the reasons for this stark downturn extended well beyond the money being spent on The Sierra Network — fodder for future articles on this site — the latter certainly wasn’t helping the situation any. The online service alone lost $5 million that year. To this point, it had cost its parent $7.5 million over and above the revenue it had managed to generate during the period of its existence — or about the cost of making ten single-player multimedia adventure games and then giving them all away for free. Sierra was in the confusing position of having collected a fair number of subscribers for their online service, yet not seeing those numbers translate into less red ink on the bottom line. The annual report for fiscal 1993 reflects the frustration this was causing inside the parent company. “There can be no assurance that costs will not become prohibitive and threaten the economic viability of the network,” it states. “Further, there can be no assurance the revenue growth rate will continue into the future or that The Sierra Network will ever become profitable.” Ken Williams had had high hopes for The Sierra Network — hopes, one might even say, that brought him as close as such a hard-nosed businessman could ever come to real idealism — but he had never been noted for his patience with money-losing ventures. “To obtain necessary funding of our marketing campaigns and new product-development efforts for The Sierra Network,” concludes the annual report, “we sought a strategic partner who could bring capital, a well-respected brand name, and a large customer base.” That partner was to be AT&T. “If you’re a young online service out to compete with the big boys,” wrote John Williams in Sierra’s magazine, “AT&T is the kind of friend you want to have.”

On July 28, 1993, the deal was consummated after months of talks. AT&T bought a 20-percent stake in The Sierra Network, while General Atlantic Partners, a venture-capital firm who had done much to broker the deal, bought another 20 percent. But of almost more import than the initial sale was the statement that the long-term plan was for AT&T “eventually to assume controlling interest.” Sierra, trying to dig themselves out of a financial hole, were gradually divesting from their grandest experiment.

Because it made little sense to continue to call an online service that would be run with decreasing input from Sierra proper The Sierra Network, it was rechristened The ImagiNation Network. In a letter to his subsidiary’s employees, Ken Williams said the things that bosses generally do under such circumstances, promising that “there will be no significant changes as a result of this partnership” — right before informing his charges of all the things that would be changing. For example, they would soon be moving out of The Old Barn and, indeed, out of Oakhurst entirely, with its “inadequate communications links and unreliable electric power.” Instead of continuing as a closed playground curated solely by Sierra, ImagiNation would become “open” to “developers of entertainment, information, and transaction software and services.” In keeping with this new spirit of openness, a bridge of sorts would be built between ImagiNation and Prodigy to allow the latter’s 2.2 million subscribers access to all the delights of SierraLand, LarryLand, and MedievaLand. Thus Ken Williams and his online service came full circle, back to the original motivator.

On November 15, 1994, AT&T bought all remaining ImagiNation shares from Sierra and General Atlantic Partners for $40 million. While the former was still under contract to provide technical support and even to build occasional additions and enhancements, their active role in steering the service ended here if not earlier. In their eyes it was now, depending on which Sierra insider was doing the looking, either a failed experiment or a worthwhile venture that had had to be set free in order to reach its full potential. Sadly, the verdict of history would lean toward holders of the first view.

There is, however, one fascinating might-have-been associated with this final stage of The Sierra Network story. Among the documents in the Sierra archive at the Strong Museum of Play is a letter to Ken Williams from Bill Gates of Microsoft. It’s dated May 5, 1993, and is written in response to the impending initial buy-in by AT&T, which was already an open secret in the tech sector by that date. Gates, it seems, had wanted in on The Sierra Network himself. He’s more than a little miffed that Williams chose AT&T over Microsoft.

I am really disappointed you didn’t talk with us further after we sent our first proposal for working together on your Network. We feel that working with us would have provided the best deal for your shareholders since we would have paid more than AT&T and would have provided more of an outlet for the creative work at Sierra. Some of the key differences between the AT&T and Microsoft proposals are:

A. We believe in the entertainment service. We would have put some of our best people onto scaling up the marketing and technology immediately. AT&T is simply hiring a new person in and seeing what happens while adding priorities relating to new platforms when the focus should be cementing over 200,000 subscribers.

B. All of our online efforts would have been focused on the one network, providing for synergy. AT&T has their Eastlink, Telescript, and other consumer-network efforts completely separated from TSN.

C. Microsoft is focused on online activities. If you had spent more time with Bob Allen and me, the difference would have become clear.

Just why Ken Williams spurned such an enthusiastic, deep-pocketed, and comparatively agile suitor in favor of the rather hidebound AT&T is unknown to me. Had he chosen another course, the latter-day history of his personal passion project would, at the very least, have been very different.

As it happened, though, the most interesting and innovative stage of the former Sierra Network’s history was already behind it by the time Bill Gates wrote his letter. SierraLand, LarryLand, and MedievaLand remained around for some time to come, descending gradually into a homey decrepitude, but AT&T struggled with little success to build anything new and compelling around them. On August 7, 1996, America Online bought the service from AT&T for an undisclosed amount. There its last remnants were gradually engulfed and devoured by its owner’s higher-profile offerings. And thus passed into history Ken Williams’s unique, perhaps impractical but certainly romantic vision for an embodied online community — for, one might even say, the online service as virtual world. It would be many years before our real world would see its like again.

(Sources: the book On the Way to the Web: The Secret History of the Internet and Its Founders by Michael A. Banks; Sierra’s official magazines from Spring 1989, Fall 1989, Spring 1990, Summer 1990, Spring 1991, Summer 1991, Fall 1991, Spring 1992, Fall 1992, Winter 1992, June 1993, Summer 1993, and Holiday 1993; Computer Gaming World of November 1991 and December 1992; Electronic Games of December 1992; New York Times of April 12 1988, May 2 1993, July 18 1993, and August 19 1993; Washington Post of November 9 1992; San Francisco Chronicle of August 7 1996; Matt Barton’s YouTube interview with Susan Manley; press releases, annual reports, and other internal and external documents from the Sierra archive at the Strong Museum of Play.)