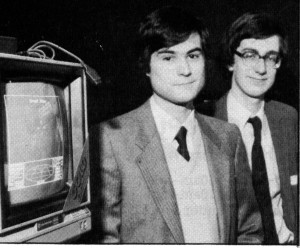

In December of 1984 Sir Clive Sinclair and Chris Curry, heads of those leading lights of the British PC revolution Sinclair Research and Acorn Computers respectively, gave a Daily Mirror columnist named Michael Jeacock a Christmas gift for the ages. Like Jeacock, Sinclair and Curry were having a drink — separately — with colleagues in the Baron of Beef pub, a popular watering hole for the hackers and engineers employed in Cambridge’s “Silicon Fen.” Spotting his rival across the room, Sinclair marched up to him and started to give him a piece of his mind. It seemed he was very unhappy about a recent series of Acorn advertisements which accused Sinclair computers of shoddy workmanship and poor reliability. To make sure Curry fully understood his position, he emphasized his words with repeated whacks about the head and shoulders with a rolled-up newspaper. Curry took understandable exception, and a certain amount of pushing and shoving ensued, although no actual punches were thrown. The conflict apparently broke out again later that evening at Shades, a quieter wine bar to which the two had adjourned to patch up their differences — unsuccessfully by all indications.

If you know anything about Fleet Street, you know how they reacted to a goldmine like this. Jeacock’s relatively staid account which greeted readers who opened the Christmas Eve edition of the Daily Mirror was only the beginning. Soon the tabloids were buzzing gleefully over what quickly became a full-blown “punch-up.” Some wrote in a fever of indignation over such undignified antics; Sinclair had just been knighted, for God’s sake. Others wrote in a different sort of fever: another Daily Mirror columnist, Jean Rook, wrote that she found Sinclair’s aggression sexually exciting.

It would be a few more months before the British public would begin to understand the real reason these middle-aged boffins had acted such fools. Still heralded publicly as the standard bearers of the new British economy, they were coming to the private realization that things had all gone inexplicably, horribly wrong for their companies. Both were staring down a veritable abyss, with no idea how to pull up or leap over. They were getting desperate — and desperation makes people behave in undignified and, well, desperate ways. They couldn’t even blame their situations on fate and misfortune, even if 1984 had been a year of inevitable changes and shakeouts which had left the software industry confused by its contradictory signs and portents and seen the end or the beginning of the end of weak sisters on the hardware side like Dragon, Camputers, and Oric. No, their situations were directly attributable to decisions they had personally made over the last eighteen months. Each made many of these decisions against his better judgment in the hope of one-upping his rival. Indeed, the corporate rivalry that led them to a public bar fight — and the far worse indignities still to come — has a Shakespearian dimension, being bound up in the relationship between these two once and future friends, each rampantly egotistical and deeply insecure in equal measure and each coveting what the other had. Rarely does business get so personal.

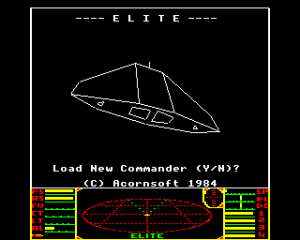

Acorn’s flagship computer, the BBC Micro, is amusingly described by Francis Spufford in Backroom Boys as the Volvo of early British computers: safe, absurdly well-engineered and well-built, expensive, and just a little bit boring. Acorn had taken full advantage of the BBC’s institutional blessing to sell the machine in huge quantities to another set of institutions, the British school system; by the mid-1980s some 90% of British schools had BBC Micros on the premises. Those sales, combined with others to small businesses and to well-heeled families looking for a stolid, professional-quality machine for the back office — i.e., the sorts of families likely to have a Volvo in the driveway as well — were more than enough to make a booming business of Acorn.

Yet when the person on the street thought about computers, it wasn’t Curry’s name or even Acorn’s that popped first to mind. No, it was the avuncular boffin Uncle Clive and his cheap and cheerful Spectrum. It was Sinclair who was knighted for his “service to British industry”; Sinclair who was sought out for endless radio, television, and print interviews to pontificate on the state of the nation. Even more cuttingly, it was the Spectrum that a generation of young Britons came to love — a generation that dutifully pecked out their assignments on the BBC Micros at their schools and then rushed home to gather around their Speccys and have some fun. Chris Curry wanted some of their love as well.

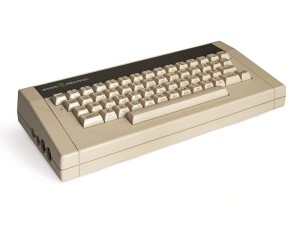

Enter in 1983 the Acorn Electron, a radically cost-reduced version of the BBC Micro designed to take on the Spectrum on its own turf. Enthusiasm for the Electron amongst the rank and file at Acorn was questionable at best. Most were not afflicted with Curry’s need to show up his old boss, but rather manifested a strain of stuffy Cambridge elitism that would cling to Acorn throughout its history. They held Sinclair’s cheap machines and the games they played in a certain contempt. They were happy to cede that segment to him, would rather be working on innovative new technology — Acorn had already initiated a 32-bit RISC processor project that would eventually result in the ubiquitous ARM architecture that dominates smartphones and tablets today — than repackaging old for mewling schoolchildren. Curry had to struggle mightily to push the Electron project through in the face of such indifference.

A price of £200, about half that of the BBC Micro, would get buyers the same 32 K of memory and the same excellent BASIC, albeit in a smaller, less professional case. However, the Electron’s overall performance was sharply curtailed by an inefficient (but cheaper) new memory configuration. The Electron’s sound capabilities also suffered greatly by comparison with its big brother, and the BBC Micro’s Mode 7, a text-only display mode that programmers loved because it greatly reduced the amount of precious memory that needed to be allocated to the display, was eliminated entirely. And, much cheaper than the BBC Micro though it may have been, it was still more expensive than the Spectrum. On paper it would seem quite a dubious proposition. Still, a considerable number of punters went for it that Christmas of 1983, the very peak of the British micro boom. Many were perhaps made willing to part with a bit more cash by the Electron’s solidity and obviously superior build quality in comparison to the Speccy.

But now Curry found himself in a truly heartbreaking position for any captain of industry: he couldn’t meet the demand. Now that it was done, many months behind schedule, problems with suppliers and processes which no one had bothered to address during development meant that Electrons trickled rather than poured into stores. “We’re having to disappoint customers,” announced a spokeswoman for W.H. Smith. “We are not able to supply demand. What we have has sold out, and while we are expecting more deliveries the amount will still be well below demand.” By some estimates, Acorn missed out on as many as 100,000 Electron sales that Christmas. Worse, most of those in W.H. Smith and other shops who found the Electrons sold out presumably shrugged and walked away with a Spectrum or a Commodore 64 instead — mustn’t disappoint the children who expected to find a shiny new computer under the tree.

Never again was the lesson that Curry took away from the episode. Whatever else happened, he was damn sure going to have enough Electrons to feed demand next Christmas. Already in June of 1984 Curry had Acorn start placing huge orders with suppliers and subcontractors. He filled his warehouses with the things, then waited for the big Christmas orders to start. This time he was going to make a killing and give old Clive a run for his money.

The orders never came. The home-computer market had indeed peaked the previous Christmas. While lots of Spectrums were sold that Christmas of 1984 in absolute numbers, it wasn’t a patch on the year before. And with the Spectrum more entrenched than ever as the biggest gaming platform in Britain, and the Commodore 64 as the second biggest, people just weren’t much interested in the Electron anymore. Six months into the following year Acorn’s warehouses still contained at least 70,000 completed Electrons along with components for many more. “The popular games-playing market has become a very uncomfortable place to be. Price competition will be horrific. It is not a market we want to be in for very long,” said Curry. The problem was, he was in it, up to his eyebrows, and he had no idea how to get out.

Taking perhaps too much to heart Margaret Thatcher’s rhetoric about her country’s young microcomputer industry as a path to a new Pax Britannia, Curry had also recently made another awful strategic decision: to push the BBC Micro into the United States. Acorn spent hugely to set up a North American subsidiary and fund an advertising blitz. They succeeded only in learning that there was no place for them in America. The Apple II had long since owned American schools, the Commodore 64 dominated gaming, and IBM PCs and compatibles ruled the world of business computing. And the boom days of home computing were already over in North America just as in Britain; the industry there was undergoing a dramatic slowdown and shakeout of its own. What could an odd British import with poor hardware distribution and poorer software distribution do in the face of all that? The answer was of course absolutely nothing. Acorn walked away humbled and with £10 to £12 million in losses to show for their American adventure.

To add to the misery, domestic sales of the BBC Micro, Acorn’s bread and butter, also began to collapse as 1984 turned into 1985. Preoccupied with long-term projects like the RISC chip as well as short-term stopgaps like the Electron, Acorn had neglected the BBC Micro for far too long. Incredibly, the machine still shipped with just 32 K of memory three years after a much cheaper Spectrum model had debuted with 48 K. This was disastrous from a marketing standpoint. Salespeople on the high streets had long since realized that memory size was the one specification that virtually every customer could understand, that they used this figure along with price as their main points of comparison. (It was no accident that Commodore’s early advertising campaign for the 64 in the United States pounded relentlessly and apparently effectively on “64 K” and “$600” to the exclusion of everything else.) The BBC Micro didn’t fare very well by either metric. Meanwhile the institutional education market had just about reached complete saturation. When you already own 90% of a market, there’s not much more to be done there unless you come up with something new to sell them — something Acorn didn’t have.

How was Acorn to survive? The City couldn’t answer that question, and the share price therefore plunged from a high of 193p to as low as 23p before the Stock Exchange mercifully suspended trading. A savior appeared just in time in the form of the Turin, Italy-based firm Olivetti, a long-established maker of typewriters, calculators, and other business equipment, including recently PCs. Olivetti initially purchased a 49 percent stake in Acorn. When that plus the release of a stopgap 64 K version of the BBC Micro failed to stop the bleeding — shares cratered to as low as 9p and trading had to be suspended again — Olivetti stepped in again to up their stake to 80 percent and take the company fully under their wing. Acorn would survive in the form of an Olivetti subsidiary to eventually change the world with the ARM architecture, but the old dream for Acorn as a proudly and independently British exporter and popularizer of computing was dead, smothered by, as wags were soon putting it, “the Shroud of Turin.”

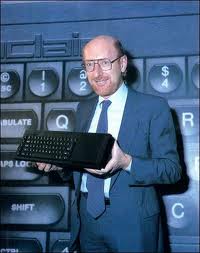

If Chris Curry wanted the popular love that Clive Sinclair enjoyed, Sir Clive coveted something that belonged to Curry: respectability. The image of his machines as essentially toys, good for games and perhaps a bit of BASIC-learning but not much else, rankled him deeply. He therefore decided that his company’s next computer would not be a direct successor to the Spectrum but rather a “Quantum Leap” into the small-business and educational markets where Acorn had been enjoying so much success.

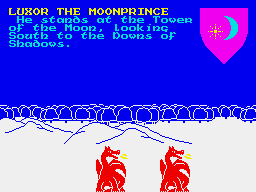

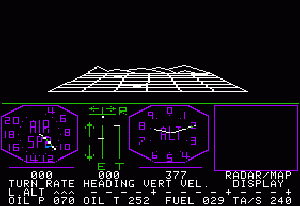

He shouldn’t have bothered. While the Electron was a competent if somewhat underwhelming little creation, the Sinclair QL was simply botched every which way from Tuesday right from start to finish. Apparently for marketing reasons as much as anything else, Sir Clive decided on a chip from the new Motorola 68000 line that had everyone talking. Yet to save a few pounds he insisted that his engineers use the 68008 rather than the 68000 proper, the former being a crippled version of the latter with an 8-bit rather than 16-bit data bus and, as a result, about half the overall processing potential. He also continued his bizarre aversion to disk drives, insisting that the QL come equipped with two of his Microdrives instead — a classically Sinclairian bit of tortured technology that looked much like one of those old lost and unlamented 8-track audio tapes and managed to be far slower than a floppy disk and far less reliable than a cassette tape (previously the most unreliable form of computer storage known to man). The only possible justification for the contraption was sheer bloody-mindedness — or anticipation of the money Sinclair stood to make as the sole sellers of Microdrive media if they could ever just get the punters to start buying the things. These questionable decisions alone would have been enough to torpedo the QL. They were, however, just the tip of an iceberg. Oh, what an iceberg…

The QL today feels like an artifact from an alternate timeline of computing in which the arrival of new chips and new technologies didn’t lead to the paradigm shifts of our own timeline. No, in this timeline things just pretty much stayed as they had been, with computers booting up to a BASIC environment housed in ROM and directed via arcane textual commands. The QL must be one of the most profoundly un-visionary computers ever released. The 68000 line wasn’t important just because it ran faster than the old 8-bit Z80s and 6502s; Intel’s 16-bit 8086 line had been doing that for years. It was important because, among other things, its seven levels of external interrupts made it a natural choice for the new paradigm of the graphical user interface and the new paradigm of programming required to write for a GUI: event-driven (as opposed to procedural) programming. This is the reason Apple chose it for their revolutionary Lisa and Macintosh. Sinclair, however, simply used a 68008 like a souped-up Z80, leaving one feeling like they’ve rather missed a pretty significant point. It’s an indictment that’s doubly damning in light of Sir Clive’s alleged role at Sinclair as a sort of visionary-in-chief — or, to choose a particularly hyperbolic contemporary description from The Sun, as “the most prodigious inventor since Leonardo.” But then, as we shall see, computers didn’t ultimately have a lot to do with Sir Clive’s visions.

The big unveiling of the QL on January 12, 1984, was a landmark of smoke and mirrors even by Sinclair’s usual standards. Sir Clive declared there that the QL would begin shipping within 28 days to anyone who cared to order one at the low price of £400, despite the fact that no functioning QL actually existed. I don’t mean, mind you, that the prototypes had yet to go into production. I mean rather that no one at Sinclair had yet managed to cobble together a single working machine. Press in attendance were shown non-interactive demonstrations played back on monitors from videotape, while the alleged prototype was kept well away from them. Reporters were told that they could book a review machine, to be sent to them “soon.”

The question of just why Sinclair was in such a godawful hurry to debut the QL is one that’s never been satisfactorily answered. Some have claimed that Sir Clive was eager to preempt Apple’s unveiling of the Macintosh, scheduled for less than two weeks later, but I tend to see this view as implying an awareness of the international computer industry and trends therein that I’m not sure Sir Clive possessed. One thing, however, is clear: the oft-repeated claim that the QL represents the first mass-market 68000-based computer doesn’t hold water. Steve Jobs debuted a working Macintosh on January 24, 1984, and Apple started shipping the Macintosh months before Sinclair did the QL.

As those 28 days stretched into months, events went through the same cycle that had greeted previous Sinclair launches: excitement and anticipation fading into anger and accusations of bad faith and, soon enough, yet another round of investigations and threats by the Advertising Standards Authority. Desperate to show that the QL existed in some form and avoid legal action on behalf of the punters whose money they’d been holding for weeks or months, Sinclair hand-delivered a few dozen machines to journalists and customers in April. These sported an odd accessory: a square appendage hanging off the back of the otherwise sleek case. It seems Sinclair’s engineers had realized at some late date that they couldn’t actually fit everything they were supposed to inside the case. By the time QLs finally started shipping in quantity that summer the unwanted accessory had been removed and its contents somehow stuffed inside the case proper, but that turned out to have been the least of the machine’s problems.

Amongst the more troubling of these was a horrid keyboard, something of another Sinclair tradition by now. Sinclair did deign to give the new machine actual plastic keys in lieu of the famous “dead flesh” rubber keys of the Spectrum, but the keys still rested upon a cheap membrane rather than having the mechanical action of such high-flying competitors as the Commodore VIC-20. The keyboard was awful to type on, a virtual kiss of death all by itself for a supposed business computer. And it soon emerged that the keyboard, like everything else on the QL, didn’t work properly on even its own limited terms. Individual keys either stuck or didn’t register, or did both as the mood struck them. Reports later emerged that Sinclair had actually solicited bids for a mechanical keyboard from a Japanese manufacturer and found it would cost very little if anything more than the membrane job, but elected to stick with the membrane because it was such a “Sinclair trademark.” The mind boggles.

And then there were the performance problems brought on by a perfect storm of a crippled CPU, the Microdrives, and the poorly written business software that came with the machine. Your Computer magazine published the following astonishing account of what it took to save a 750-word document in the word processor:

1. Press F3 key followed by 6. A period of 35 seconds elapses by which time the computer has found the save section of Quill and then asks if I wish to save the default file, i.e. the file I am working on.

2. Press ENTER. After a further 10 seconds the computer finds that the file already exists and asks if I wish to overwrite it.

3. Press Y. A period of 100 seconds elapses while the old file is erased and the new one saved and verified in its place. The user is then asked if he wishes to carry on with the same document.

4. Press ENTER. Why a further 25 seconds is required here is beyond me as the file must be in memory as we have just saved it. Unfortunately, the file is now at the start, so to get back to where I was:

5. Press F3 key then G followed by B. The Goto procedure to get to the bottom of the file, a further 28 seconds.

For those keeping score, that’s 3 minutes and 18 seconds to save a 750-word document. For a 3000-word document, that time jumped to a full five minutes.

Your Computer concluded their review of the QL with a prime demonstration of the crazily mixed messaging that marked all coverage of the machine. It was “slightly tacky,” “the time for foisting unproven products on the marketplace has gone,” and “it would be a brave business which would entrust essential data to Microdrives.” Yet it was also a “fascinating package” and “certain to be a commercial success.” It arguably was “fascinating” in its own peculiar way. “Commercial success,” however, wasn’t in the cards. Sinclair did keep plugging away at the QL for months after its release, and did manage to make it moderately more usable. But the damage was long since done. Even the generally forgiving British public couldn’t accept the eccentricities of this particular Sinclair creation. Sales were atrocious. Still, Sir Clive, never one to give up easily, continued to sell and promote it for almost two years.

There’s a dirty secret about Sir Clive Sinclair the computer visionary that most people never quite caught on to: he really didn’t know that much about computers, nor did he care all that much about them. Far from being the “most prodigious inventor since Leonardo,” Sir Clive remained fixated for decades on exactly two ideas: his miniature television and his electric car. The original Sinclair ZX80 had been floated largely to get Sinclair Research off the ground so that he could pursue those twin white whales. Computers had been a solution to a cashflow problem, a means to an end. His success meant that by 1983 he had the money he needed to go after the television and the car, the areas where he would really make his mark, full on. Both being absolutely atrocious ideas, this was bad, bad news for anyone with a vested interest in Sinclair Research.

The TV80 was a fairly bland failure by Sinclair standards: he came, he spent millions manufacturing thousands of devices that mostly didn’t work properly and that nobody would have wanted even if they had, and he exited again full of plans for the next Microvision iteration, the one that would get it right and convince the public at last of the virtues of a 2-inch television screen. But the electric car… ah, that one was one for the ages, one worthy of an honored place beside the exploding watches of yore. Sir Clive’s C5 electric tricycle was such an awful idea that even his normally pliable colleagues resisted letting Sinclair Research get sucked up in it. He therefore took £8.6 million out to found a new company, Sinclair Vehicles.

The biggest problem in making an electric car, then and now, is developing batteries light enough, powerful enough, and long-lasting enough to rival gasoline or diesel. Researchers were a long way away still in 1984. A kilogram of gasoline has an energy potential of 13,000 watt-hours; a state-of-the-art lead-acid battery circa 1984 had an energy potential of 50 watt-hours. That’s the crux of the problem; all else is relative trivialities. Having no engineering solution to offer for the hard part of the problem, Sinclair solved it through a logical leap that rivals any of Douglas Adams’s comedic syllogisms: he would simply pretend the hard problem didn’t exist and just do the easy stuff. From his adoring biography The Sinclair Story:

Part of the ground-up approach was not to spend enormous amounts trying to develop a more efficient battery, but to make use of the models available. Sinclair’s very sound reasoning was that a successful electric vehicle would provide the necessary push to battery manufacturers to pursue their own developments in the fullness of time; for him to sponsor this work would be a misplacement of funds.

There’s of course a certain chicken-or-egg problem inherent in this “sound reasoning,” in that the reason a “successful electric vehicle” didn’t yet exist was precisely because a successful electric vehicle required improved battery technology to power it. Or, put another way: if you could make a successful electric vehicle without improved batteries, why would its existence provide a “push to battery manufacturers?” Rather than a successful electric vehicle, Sir Clive made the QL and Black Watch of electric vehicles all rolled into one, an absurd little tricycle that was simultaneously underwhelming (to observe) and terrifying (to actually drive in traffic).

He unveiled the C5 on January 10, 1985, almost exactly one year after the QL dog-and-pony show and for the same price of £400. The press assembled at Alexandria Palace couldn’t help but question the wisdom of unveiling an open tricycle on a cold January day. But, once again, logistics were the least of the C5’s problems. A sizable percentage of the demonstration models simply didn’t work at all. The journalists dutifully tottered off on those that did, only to find that the advertised top speed of 15 mph was actually more like 5 mph — a brisk walking speed — on level ground. The batteries in many of the tricycles went dead or overheated — it was hard to tell which — with a plaintive little “Peep! Peep!” well before their advertised service range of 20 miles. Those journalists whose batteries did hold out found that they didn’t have enough horsepower to get up the modest hill leading back to the exhibition area. It was a disgruntled and disheveled group of cyclists who straggled back to Sir Clive, pedaling or lugging the 30-kilogram gadgets alongside. They could take comfort only in the savaging they were about to give him. When the press found out that the C5 was manufactured in a Hoover vacuum-cleaner plant and its motor was a variation on one developed for washing machines, the good times only got that much better. If there’s a single moment when Sir Clive turned the corner from visionary to laughingstock, this is it.

Sinclair Research wasn’t doing a whole lot better than its founder as 1984 turned into 1985. In addition to the huge losses sustained on the QL and TV80 fiascoes, Sinclair had, like Acorn, lost a bundle in the United States. Back in 1982, they had cut a deal with the American company Timex, who were already manufacturing all of their computers for them from a factory in Dundee, Scotland, to export the ZX81 to America as the Timex Sinclair 1000. It arrived in July of 1982, just as the American home-computing boom was taking off. Priced at $99 and extravagantly advertised as “the first computer under $100,” the TS 1000 sold like gangbusters for a short while; for a few months it was by far the bestselling computer in the country. But it was, with its 2 K of memory, its calculator keyboard, and its blurry text-only black-and-white display, a computer in only the most nominal sense. When Jack Tramiel started in earnest his assault on the low-end later in the year with the — relatively speaking — more useful and usable Commodore VIC-20, the TS 1000 was squashed flat.

Undeterred, Timex and Sinclair tried again with an Americanized version of the Spectrum, the TS 2068. With the best of intentions, they elected to improve the Speccy modestly to make it more competitive in America, adding an improved sound chip, a couple of built-in joystick ports (British Speccy owners had to buy a separate interface), a couple of new graphics modes, a cartridge port, even a somewhat less awful version of Sinclair’s trademark awful keyboards. The consequence of those improvements, however, was that most existing Spectrum software became incompatible. This weird little British machine with no software support was priced only slightly less than the Commodore 64 with its rich and growing library of great games. It never had a chance. Timex, like other big players such as Texas Instruments and Coleco, were soon sheepishly announcing their withdrawal from the home-computer market, vanquished like the others by Commodore.

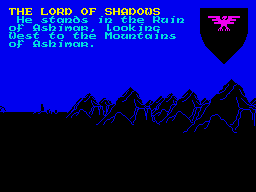

Back in Britain, meanwhile, it was becoming clear that, as if Sinclair hadn’t already had enough problems, domestic sales of the Spectrum were beginning to slow. Sinclair was still in a dominant position, owning some 40 percent of the British market. However, conventional wisdom had it that that market was becoming saturated; by late 1984 most of the people in Britain who were likely to buy a computer had already done so, to the tune of far more sales per capita than any other country on the planet. Sinclair’s only chance to maintain sales would seem to be to sell new machines to those who already owned older models. Yet they had pissed away the time and resources needed to create a next-generation Speccy on the QL. In desperation they rushed out something called the Spectrum Plus for Christmas 1984: a slightly more substantial-looking Spectrum with a better keyboard like that of the QL (still not a genuinely good one, of course; “Sinclair trademark” and all that). With no changes to its actual computing capabilities, this wasn’t exactly a compelling upgrade package for current Spectrum owners. And, Sinclair still being Sinclair, the same old problems continued; most Spectrum Pluses arrived with several of the vaunted new plastic keys floating around loose in the box.

By mid-1985, Sinclair’s position wasn’t a whole lot better than that of Acorn. They were drowning in unsold inventories of Spectrums and QLs dating back to the previous Christmas season and even before, mired in debt, and without the resources to develop the Spectrum successor they desperately needed.

Then it seemed that their own Olivetti-equivalent had arrived. In a “World Exclusive!” article in the June 17, 1985, edition, the Daily Mirror announced that “Maxwell Saves Sinclair.” The Maxwell in question was the famous British tycoon and financier Robert Maxwell, who would inject some £12 million into the company. In return, Sir Clive would have to accept some adult supervision: he would become a “life president” and consultant, with Maxwell installing a management team of his own choosing. Everyone was relieved, even Margaret Thatcher. “The government has been aware that these talks have been going on and welcomes any move to put the Sinclair business on a firm footing,” said a spokesman.

Then, not quite two months after the carefully calibrated leak to the Daily Mirror, Maxwell suddenly scuttled the deal. We’re not quite sure why. Some have said that, after a thorough review of Sinclair’s books, Maxwell concluded the company was simply irredeemable; some that Sir Clive refused to quietly accept his “life president” post and go away the way Maxwell expected him to; some that Sir Clive planned to go away all too soon, taking with him a promising wafer-scale chip integration process a few researchers had been working on to serve as his lifeboat and bridge to yet another incarnation of an independent Sinclair, as the ZX80 had served as a bridge between the Sinclair Radionics of the 1970s and the Sinclair Research of the 1980s. Still others say that Sir Clive was never serious about the deal, that the whole process was a Machiavellian plot on his part to keep his creditors at bay until the Christmas buying season began to loom, after which they would continue to wait and see in the hope that Sinclair could sell off at least some of all that inventory before the doors were shut. This last, at least, I tend to doubt; like the idea that he staged the QL unveiling to upstage the Macintosh, it ascribes a level of guile and business acumen to Sir Clive that I’m not sure he possessed.

At any rate, Sinclair Research staggered into 1986 alive and still independent but by all appearances mortally wounded. A sign of just how far they had fallen came when they had to beg the next Spectrum iteration from some of the people they were supposed to be supplying it to: Spain’s Investrónica, signatories to the only really viable foreign distribution deal they had managed to set up. The Spectrum 128 was a manifestation of Investrónica’s impatience and frustration with their partner. After waiting years for a properly updated Spectrum, they had decided to just make their own. Created as it was quickly by a technology distributor rather than technology developer, the Spectrum 128 was a bit of a hack-and-splice job, grafting an extra 80 K of memory, an improved sound chip, and some other bits and pieces onto the venerable Speccy framework. Nevertheless, it was better than nothing, and it was compatible with older Speccy games. Sinclair Research scooped it up and started selling it in Britain as well.

The state of Acorn and Sinclair as 1986 began was enough to trigger a crisis of faith in Britain. The postwar era, and particularly the 1970s, had felt for many people like the long, slow unraveling of an economy that had once been the envy of the world. It wasn’t only Thatcher’s Conservatives who had seen Sir Clive and Acorn as standard bearers leading the way to a new Britain built on innovation and silicon. If many other areas of the economy were finally, belatedly improving after years and years of doldrums, the sudden collapse of Sinclair and Acorn nevertheless felt like a bucket of cold water to the dreamer’s face. All of the old insecurities, the old questions about whether Britain could truly compete on the world economic stage came to the fore again to a degree thoroughly out of line with what the actual economic impact of a defunct Acorn and Sinclair would have been. Now those who still clung to dreams of a silicon Britain found themselves chanting an unexpected mantra: thank God for Alan Sugar.

Sugar, the business titan with the R&B loverman’s name, had ended his formal schooling at age 16. A born salesman and wheeler and dealer, he learned his trade as an importer and wholesaler on London’s bustling Tottenham Court Road, then as now one of the densest collections of electronics shops in Europe. He founded his business, Amstrad, literally out of the back of a van there in 1968. By the late 1970s he had built Amstrad into a force to be reckoned with as purveyors of discount stereo equipment, loved by his declared target demographic of “the truck driver and his wife” as much as it was loathed by audiophiles.

He understood his target market so well because he was his target market. An unrepentant Eastender, he never tried to refine his working-class tastes, never tried to smooth away his Cockney diction despite living in a country where accent was still equated by many with destiny. The name of his company was itself a typical Cockneyism, a contraction of its original name of A.M.S. Trading Company (“A.M.S.” being Sugar’s initials). Sugar:

There was the snooty area of the public that would never buy an Amstrad hi-fi and they went out and bought Pioneer or whatever, and they’re 5 percent of the market. The other 95 percent of the market wants something that makes a noise and looks good. And they bought our stuff.

An Amstrad stereo might not be the best choice for picking out the subtle shadings of the second violin section, but it was just fine for cranking out the latest Led Zeppelin record good and loud. Sugar’s understanding of what constituted “good enough” captured fully one-third of the British stereo market for Amstrad by 1982, far more than any other single company.

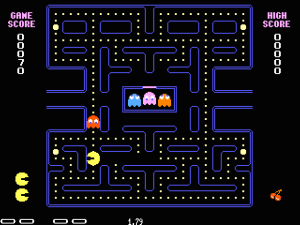

In 1983, Sugar suddenly decided that Amstrad should build a home computer to compete with Sinclair, Acorn, and Commodore. Conventional wisdom would hold that this was absolutely terrible timing. Amstrad was about to jump into the market just in time for it to enter a decline. Still, if Sugar could hardly have been aware of what 1984 and 1985 would bring, he did see some fairly obvious problems with the approach of his would-be competitors which he believed Amstrad could correct. In a sense, he’d been here before.

Stereos had traditionally been sold the way that computer systems were in 1983: as mix-and-match components — an amplifier here, a tape deck and record player there, speakers in that corner — which the buyer had to purchase separately and assemble herself. One of Sugar’s greatest coups had come when he had realized circa 1978 that his truck drivers hated this approach at least as much as the audiophiles reveled in it. They hated comparing a bunch of gadgets with specifications they didn’t understand anyway; hated opening a whole pile of boxes and trying to wire everything together; hated needing four or five sockets just to power one stereo. Amstrad therefore introduced the Tower System: one box, one price, one socket — plug it in and go. It became by far their biggest seller, and changed the industry in the process.

Amstrad’s computer would follow the same philosophy, with the computer, a tape drive, and a monitor all sold as one unit. The included monitor in particular would become a marketing boon. Monitors being quite unusual in Britain, many a family was wracked with conflict every evening over whether the television was going to be used for watching TV or playing on the Speccy. The new Amstrad would, as the advertisements loudly proclaimed, make all that a thing of the past.

The CPC-464 computer which began shipping in June of 1984 was in many other ways a typical Amstrad creation. Sugar, who considered “boffin” a term of derision, was utterly uninterested in technological innovation for its own sake. Indeed, Sugar made it clear from the beginning that, should the CPC-464 disappoint, he would simply cut his losses and drop the product, as he had at various times televisions, CB radios, and car stereos before it. He was interested in profits, not the products which generated them. So, other than in its integrated design the CPC-464 innovated nowhere. It instead was just a solid, conservative computer that was at least in the same ballpark as the competition in every particular and matched or exceeded it in most: 64 K of memory, impressive color graphics, a decent sound chip, a more than decent BASIC. Build quality and customer service were, if not quite up to Acorn’s standards, more than a notch or two above Sinclair’s and more than adequate for a computer costing about £350 with tape drive and color monitor. Amstrad also did some very smart things to ease the machine’s path to consumer adoption: they paid several dozen programmers to have a modest library of games and other software available right from launch, and started Amstrad Computer User magazine to begin to build a community of users. These strategies, along with the commonsense value-for-your-pound approach of the machine itself, let the CPC-464 and succeeding machines do something almost inconceivable to the competitors collapsing around them: post strong sales that continued to grow by the month, making stereos a relatively minor part of Amstrad’s booming business within just a couple of years.

Amstrad’s results were so anomalous to those of the industry as a whole that for a considerable length of time the City simply refused to believe them. Their share price continued to drop through mid-1985 in direct defiance of rosy sales figures. It wasn’t until Amstrad’s fiscal year ended in June and the annual report appeared showing sales of £136.1 million and an increase in profits of 121 percent that the City finally began to accept that Amstrad computers were for real. Alan Sugar describes in his own inimitable way the triumphalism of this period of Amstrad’s history:

The usual array of predators, such as Dixons, W. H. Smith, and Boots, were hovering around like the praying mantis, saying, “Ha, ha, you’ve got too many computers, haven’t you? We’re going to jump on you and steal them off you and rape you when you need money badly, just like Uncle Clive.” And we said, “We haven’t got any.” They didn’t believe us, until such time as they had purged their stocks and finished raping Clive Sinclair and Acorn, and realized they had nothing left to sell. So they turned to us again in November of 1985 and said, “What about a few of your computers at cheaper prices?” We stuck the proverbial two fingers in the air, and that’s how we got price stability back into the market. They thought we were sitting on stockpiles and they were doing us a big favour. But we had no inventory. It had gone to France and Spain.

Continental Europe was indeed a huge key to Amstrad’s success. When Acorn and Sinclair had looked to expand internationally, they had looked to the hyper-competitive and already troubled home-computer market in the United States, an all too typical example of British Anglocentrism. (As Bill Bryson once wrote, a traveler visiting Britain with no knowledge of geography would likely conclude from the media and the conversations around her that Britain lay a few miles off the coast of the United States, perhaps about where Cuba is in our world, and it was the rest of Europe that was thousands of miles of ocean away.) Meanwhile they had all but ignored all that virgin territory that started just a ferry ride away. Alan Sugar had no such prejudices. He let America alone, instead pushing his computers into Spain, France, and the German-speaking countries (where they were initially sold under the Schneider imprint — ironically, another company that had gotten its start selling low-priced stereo equipment). Amstrad’s arrival, along with an increasingly aggressive push from Commodore’s West German subsidiary, marks the moment when home computers at last began to spread in earnest through Western Europe, to be greeted there by kids and hackers with just as much enthusiasm and talent as their British, American, and Japanese counterparts.

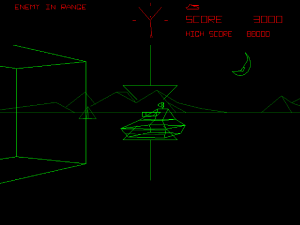

One day in early 1986, Alan Sugar received an unexpected call from Mark Souhami, manager of the Dixons chain of consumer-electronics stores. Souhami dropped a bombshell: it seemed that Sir Clive was interested in selling his computer operation to Amstrad, the only company left in the market with the resources for such an acquisition. Dixons, who still sold considerable numbers of Spectrums and thus had a vested interest in keeping the supply flowing, had been recruited to act as intermediaries. Sir Clive and Sugar soon met personally for a quiet lunch in Liverpool Street Station. Sir Clive later reported that he found Sugar “delightful” — “very pleasant company, a witty man.” Sugar was less gracious, ruthlessly mocking in private Sir Clive’s carefully cultivated “Etonian accent” and his intellectual pretensions.

At 3:00 AM on April 2, 1986, after several weeks of often strained negotiations, Amstrad agreed to buy all of the intellectual property for and existing stocks of Sinclair’s computers for £16 million. The sum would allow Sir Clive to pay off his creditors and make a clean break from the computer market to pursue his real passions. Tellingly, Sinclair Research itself along with the TV80 and the C5 were explicitly excluded from the transfer — not that Sugar had any interest in such financial losers anyway. With a stroke of the pen, Alan Sugar and Amstrad now owned 60 percent of the British home-computer market along with a big chunk of the exploding continental European. All less than two years after the CPC-464 had debuted under a cloud of doubt.

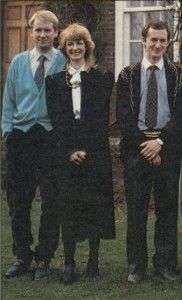

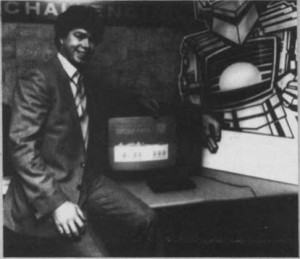

When Sugar and Sir Clive officially announced their deal at a press conference on April 7, the press rightly marked it as the end of an era. The famous photograph of their uncomfortable handshake before the assembled flash bulbs stands as one of the more indelible in the history of British computing, a passing of the mantle from Sir Clive the eccentric boffin to Sugar the gruff, rough, and ruthless man of the bottom line. British computing had lost its innocence, and things would never quite be the same again. Thatcher had backed the wrong horse in choosing Sir Clive as her personification of the new British capitalist spirit. (Sugar would get a belated knighthood of his own in 2000.) On the plus side, British computing was still alive as an independent entity, a state of affairs that had looked very doubtful just the year before. Indeed, it was poised to make a huge impact yet through Amstrad.

Those who fretted that Sugar might have bought the Spectrum just to kill it needn’t have; he was far too smart and unsentimental for that. If people still wanted Spectrums, he would give them Spectrums. Amstrad thus remade the Speccy with an integrated tape drive in the CPC line’s image and continued to sell it as the low end of their lineup into the 1990s, until even the diehards had moved on. Quality and reliability improved markedly, and the thing even got a proper keyboard at long last. The QL, however, got no such treatment; Sugar put it out of its misery without a second thought.

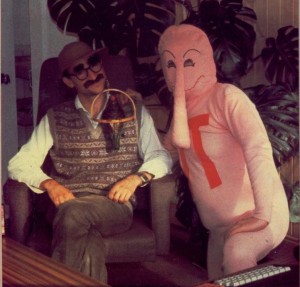

I’ll doubtless have more to say about a triumphant Amstrad and a humbled but still technically formidable Acorn in future articles. Sir Clive, however, will now ride off into the sunset — presumably on a C5 — to tinker with his electric cars and surface occasionally to delight the press with a crazy anecdote. He exited the computer market with dreams as grandiose as ever, but no one would ever quite take him seriously again. For a fellow who takes himself so manifestly seriously, that has to be a difficult thing to bear. Sinclair Research exists as a nominal corporation to this day, but for most of the past three decades its only actual employee appears to have been Sir Clive himself, still plugging away at his electric car (miniaturized televisions have not been in further evidence). I know I’ve been awfully hard on Sir Clive, but in truth I rather like him. He possessed arrogance, stubbornness, and shortsightedness in abundance, but no guile and very little greed. Amongst the rogue’s gallery of executives who built the international PC industry that practically qualifies him for sainthood. He was certainly the most entertaining computer mogul of all time, and he did manage almost in spite of himself to change Britain forever. The British public still has a heartfelt affection for the odd little fellow — as well they should. Eccentrics like him don’t come around every day.

(Much of this article was drawn from following the news items and articles in my favorite of the early British micro magazines, Your Computer, between January 1984 and May 1986. Other useful magazines: Popular Computing Weekly of November 10 1983 and January 12 1984; Sinclair User of November 1984, February 1985, and March 1985. Two business biographies of Sir Clive are recommended, one admiring and one critical: The Sinclair Story by Rodney Dale and Sinclair and the “Sunrise” Technology by Ian Adamson and Richard Kennedy respectively. The best account I’ve found of Amstrad’s early history is in Alan Sugar: The Amstrad Story by David Thomas. Good online articles: The Register’s features on the Sinclair Microdrives, the QL, and the Acorn Electron; Stairway to Hell’s reprinting of a series of articles on Acorn’s history from Acorn User magazine. Finally, by all means check out the delightful BBC docudrama Micro Men if you haven’t already and marvel that the events and personalities depicted therein are only slightly exaggerated. That film is also the source of the last picture in this article; it was just too perfect an image to resist.)