In mid-1978 Apple Computer hired Trip Hawkins, a 25-year-old with a newly minted MBA from Stanford, to work in the marketing department. He quickly became a great favorite of Steve Jobs. The two were of similar ages and similar dispositions, good looking and almost blindingly charismatic when they turned on the charm. They were soon confirmed running buddies; Hawkins later told of “smoking dope” in a Vegas hotel room during a CES show, then going down to shoot craps all night. Less superficially, they thought differently than both the technicians and engineers at Apple (like Steve Wozniak) and the older, more conventional businessmen there (like Mike Markkula and Michael Scott). Their fondest dreams were not of bytes or market share, but rather of changing the way people lived through technology. Jobs monopolized much of Hawkins’s time during the latter part of 1978, as the two talked for hours on end about what form a truly paradigm-shifting computer might take. The ideas that began here would retain, through years of chaos to come, the casual code name they initially gave them: “Lisa.”

There’s been some confusion about the origins of the name. Years later, when they began selling Lisa as an actual product, Apple tried to turn it into LISA, short for “Local Integrated Software Architecture.” This was so obviously tortured that even the fawning computer press to whom they first promoted the machine had some fun with it; “Let’s Invent Some Acronyms” was a popular variation. Some sources name Lisa as the name of “the original hardware engineer’s daughter.” Yet it’s hard to get past the fact that just before all those long conversations with Hawkins Jobs had a daughter born to an on-again/off-again girlfriend he had known since high school. They named her Lisa Nicole. The story of what followed is confused and not terribly flattering to Jobs personally (not that it’s difficult to find examples of the young Jobs behaving like a jerk). After apparently being present at the birth and helping to name the baby, not to mention naming his new pet project after her, something caused Jobs to have a sudden change of heart. He denied paternity vigorously; when asked who he thought the real father was, he charmingly said that it could be any of about 28 percent of the male population of the country. Even when a court-ordered paternity test gave him about a 95 percent chance of being the father, he continued to deny it, claiming to be sterile. A few years later, when Jobs was worth some $210 million, he was still cutting a check each month to Lisa’s mother for exactly the amount the court had ordered: $385. Only slowly and begrudgingly would he accept his daughter in the years to come. At the end of that process he finally acknowledged the origin of the computer’s name: “Obviously it was named for my daughter,” he told his official biographer Walter Isaacson shortly before his death. The “original hardware engineer” apparently referenced above, Ken Rothmuller, was even more blunt: “Jobs is such an egomaniac, do you really think he would have allowed such an important project to be named after anybody but his own child?”

Jobs and Hawkins were convinced that the Lisa needed to be not just more powerful than the likes of the Apple II, but also — and here is the real key — much easier, much more fun for ordinary people to use. They imagined a machine that would replace esoteric key presses and cryptic command prompts with a set of simple on-screen menus that would guide the user through her work every step of the way. They conceived not just a piece of hardware waiting for outside programmers to make something of it, like the Apple II, but an integrated software/hardware package, a complete computing environment tailored to friendliness and ease of use. Indeed, the software would be the real key.

But of course making software more friendly would put unprecedented demands on the hardware. This was as true then as it is today. As almost any programmer will tell you, the amount of work that goes into a program and the amount of computing horsepower it demands are directly proportional to how effortlessly it seems to operate from the user’s perspective. Clearly Jobs and Hawkins’s ideas for Lisa were beyond the capabilities of the little 6502 inside the Apple II. Yet among the other options available at the time only Intel’s new 16-bit 8086 looked like it might have the power to do the job. Unfortunately, Apple and their engineers disliked Intel and its architecture passionately, rendering that a non-option. (Generally computer makers have broken down into two camps: those who use Intel chips and derivatives such as the Zilog Z80, and those who use other chips. Until fairly recently, Apple was always firmly in the latter camp.) In the spring of 1979, with the Apple II Plus finished and with most of the other engineers occupied getting the Sara project (eventually to be known as the Apple III) off the ground, Woz therefore set to work on one hell of an ambitious project. He would make a brand new CPU in-house for Lisa, using a technique he had always favored called bit slicing.

Up to this time Lisa had had little official existence within Apple. It was just a ground for conjecture and dreaming by Jobs and his closest circle. But on July 30, 1979, it took official form at last, when Ken Rothmuller, like Woz late of nearby Hewlett Packard, came on-board to lead the project under the close eye of Jobs, who divided his time between Sara and Lisa. Sara was now envisioned as the immediate successor to the Apple II, a much improved version of the same basic technology; Lisa as the proverbial paradigm shift in computing that would come somewhat later. Most of the people whom Rothmuller hired were also HP alumni, as were many of those working on Sara; Apple in these days could seem like almost a divisional office of the larger company. This caused no small chagrin to Jobs, who considered the HP engineers the worst sort of unimaginative, plodding “Clydesdales,” but it was inevitable given Apple’s proximity to the giant.

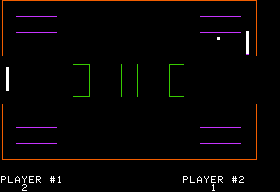

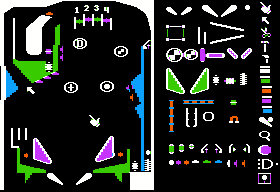

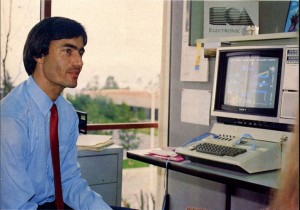

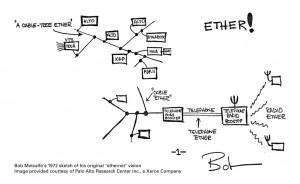

While they waited for Woz’s new processor, the Lisa people started prototyping software on the Apple II. Already a bit-mapped display that would allow the display of images and various font styles was considered essential. The early software thus ran through a custom-built display board connected to the Apple II running at a resolution of 356 X 720. At this stage the interface was to be built around “soft keys.” Each application would always show a menu of functions that were mapped to a set of programmable function keys on the keyboard. It was a problematic approach, wasteful of precious screen real estate and limited by the number of function keys on the keyboard, but it was the best anyone had yet come up with.

The original Lisa user interface, circa autumn 1979. Note the menu of “soft keys” at the bottom.

That October Rothmuller’s team assembled the first working Lisa computer around a prototype of Woz’s processor. Just as they were doing so, however, they became aware of an alternative that would let them avoid the trouble and expense of refining a whole new processor and also avoid dealing with the idiosyncrasies of Woz, who was quickly falling out of favor with management. Their new processor would have a tremendous impact on computing during the decade to come. It was the Motorola 68000.

The 68000 must have seemed like the answer to a prayer. At a time when the first practical 16-bit chips like the Intel 8086 were just making their presence felt, the 68000 went one better. Externally, it fetched and stored from memory like a 16-bit chip, but it could perform many internal operations as a 32-bit chip, while a 24-bit address bus let it address a full 16 M of memory, a truly mind-boggling quantity in 1979. It could be clocked at up to 8 MHz, and had a beautiful system of interrupts built in that made it ideal for the centerpiece of a sophisticated operating system like those that had heretofore only been seen on the big institutional computers. In short, it was simply the sleekest, sexiest, most modern microprocessor available. Naturally, Apple wanted it for the Lisa. Motorola was still tooling up to produce the chips — they wouldn’t begin coming out in quantity until the end of 1980 — but Apple was able to finagle a deal that gave them access to prototypes and pre-release samples. Woz’s processor was put on the shelf. The Lisa was now to be a 68000 machine, the CPU of the future housed in the computing paradigm of the future. It’s at this stage, with the Lisa envisioned as a soft-key-driven 68000-based computer, that Xerox PARC enters the picture.

The story of Steve Jobs’s visit to PARC in December of 1979 has passed into computer lore as a fateful instant where everything changed, one to stand alongside IBM’s visit to Digital Research the following year. Depending on your opinion of Jobs and Apple, they would either go on to refine, implement, and popularize these brilliant ideas about which Xerox themselves were clueless, or shamelessly rip off the the work of others — and then have the hypocrisy to sue still others for trying to do the same, via their “look and feel” battle with Microsoft over the Windows interface. In truth, the PARC visit was in at least some ways less momentous than conventional wisdom would have it. To begin with, the events that set the meeting in motion had little to do with the future of computing as implemented through the Lisa project or anywhere else, and a lot to do with a pressing, immediate worry afflicting Mike Markkula and Michael Scott.

Back in early 1978, Apple had been the first PC maker to produce a disk system, using the new technology of the 5 1/4″ floppy disk which had been developed by a company called Shugart Associates. Woz’s Disk II system was as important to the Apple II’s success as the Apple II itself, a night-and-day upgrade over the old slow and balky cassette tapes that enabled, amongst many other advances, the Apple II’s first killer app, VisiCalc. Apple initially bought its drives direct from Shugart, the only possible source. However, they soon became frustrated with the prices they were paying (apparently Apple’s legendarily high profit margins were justifiable for them, but not for others) and with the pace of delivery. They therefore found a cut-rate electronics manufacturer in Japan, Alps Electric Company, whom they helped to clone the Shugart drives. Through Alps they were able to get all the drives they wanted, and get them much cheaper than they could through Shugart. Trouble was, blatantly cloning Shugart’s patented technology in this way left them vulnerable to all sorts of legal action. By this time, Apple had a reputation as an up-and-coming company to watch, and was raising money toward an eventual IPO from a variety of investors. When he heard that Xerox’s financial people were interested in making an investment, Scott suddenly saw a way to protect the company from Shugart. Shugart, you see, was wholly owned by Xerox. Scott reasoned, correctly, that Xerox would not allow one of its subsidiaries to sue a company in which it had a vested interest. Apple and Xerox quickly concluded an agreement that allowed the latter to buy 100,000 shares of the former for a rather paltry $1 million. As a sort of adjunct, the two companies also agreed to do some limited technology exchange. It was this that led to Jobs’s legendary visit to PARC some months later.

The fact that it took him so long to finally visit shows that PARC’s technology was not so high on Jobs’s list of priorities. The basics of what PARC had to offer were hardly any big secret amongst people who thought about such things during the 1970s. It was something of a rite of passage for ambitious computer-science graduate students, at least those from the nearby universities, to take a tour and get a glimpse of what everyone was increasingly coming to regard as the interface of the future. Several people at Apple and even on the Lisa team were very aware of PARC’s work. Many of their ideas had already made their way into the Lisa. Reports vary somewhat, but some claim that the Lisa already had the concept of windowing and even an optional mouse before the visit to PARC. And certainly the Alto’s bitmapped display model was already present. The Lisa team member who finally convinced Jobs to visit PARC, Bill Atkinson, later claimed to wish he had never done so: “Those one and a half hours tainted everything we did, and so much of what we did was original research.”

The legendary visit to PARC was actually two visits, which took place a few days apart. The first involved a small group, perhaps no more than Atkinson and Jobs themselves. The second was a much lengthier and more in-depth demonstration that spanned most of a day, and involved most of the principal players on Lisa, including Hawkins. As Jobs later freely admitted, he saw three breakthrough technologies at PARC — the GUI, the LAN, and object-oriented programming in the form of Smalltalk — but was so taken by the first that he hardly noticed the other two. Jobs was never particularly interested in how technology was constructed, so his lack of engagement with the third is perhaps understandable. His inability to get the importance of networking, however, would become a major problem for Apple in the future. (A fun anecdote has the Jobs of a few years later, tired of being bothered about Apple’s piss-poor networking, throwing a floppy disk at his interlocutor, saying, “Here’s your fucking network!”)

Even if there weren’t as many outright revelations at PARC as legend would have it, it’s certainly true that Jobs and the rest of the Lisa team found what they saw there hugely inspiring. Suddenly all of these ideas that they had been discussing in the abstract were there, before them, realized in actual pixels. PARC showed them that it could be done. As Hawkins later put it, “We got religion.”

Of course, every religion needs a sacred text. Hawkins provided one in the spring of 1980 when he finished the 75-page “Lisa Marketing Requirements.” Far more than what its name would imply, it was in fact a blueprint for the entire project as Jobs and Hawkins now envisioned it. It’s a fascinating read today. Lisa will “portray a friendlier ‘personality’ and ‘disposition’ than ordinary computers to allow first-time users to develop the same emotional attachment with their system that they have with their car or their stereo.” Over and over occurs a phrase that was supposed to be the mission statement for PARC: “the office of the future.” Other parts, however, put the lie to the notion that Apple decided to just junk everything it had already done on the Lisa and clone the Xerox Alto. While a mouse is now considered essential, for instance, they are still holding onto the old notion of a custom keyboard with soft keys. The MR document was Hawkins’s last major contribution to Lisa. Soon after writing it, he became Apple’s head of marketing, limiting his role with Lisa.

While the HP contingent remained strongly represented, as the team grew Apple began poaching from PARC itself, eventually hiring more than fifteen ex-PARCers. Those who weren’t on board with the new, increasingly PARC-centric direction found it tough going. Rothmuller, for instance, was unceremoniously dumped for thinking too traditionally. And then, unexpectedly, Jobs himself was gone.

As 1980 drew to a close, with the IPO looming and the Apple III already starting to show signs of becoming a fiasco, CEO Michael Scott decided that he had to impose some order on the company and neuter Jobs, whose often atrocious treatment of others was bringing a steady rain of complaints down upon his desk. He therefore reorganized the entire company along much stricter operational lines. Jobs begged for the newly created Lisa division, but Scott was having none of it. Lisa after all was coming more and more to represent the long-term future of Apple, and after watching the results of his meddling in the Sara project Scott had decided that he didn’t want Jobs anywhere near it. If Jobs would just confine himself to joining Woz as Apple’s token spokesman and mascot, that would be more than enough of a contribution, thank you very much. He placed Lisa in the hands of yet another steady ex-HP man, John Couch. Jobs went off in a huff, eventually to busy himself with another project called Macintosh. From now on he would be at war with his erstwhile pet. One of his first strikes was to lure away Atkinson, an ace graphics programmer, to the Macintosh project.

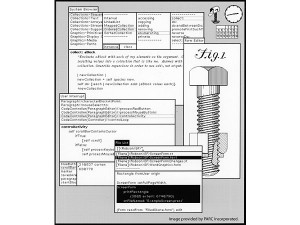

By now 68000-based prototype machines were available and software development was ramping up. Wayne Rosing was now in charge of hardware; Bruce Daniels, who had co-written the original MIT Zork and written Infocom’s first interpreter for the Apple II, in charge of the operating system; and Larry Tesler, late of PARC, in charge of the six integrated applications to be at the heart of the office of the future. They were: Lisa Draw; Lisa Write, a what-you-see-is-what-you-get word processor in the tradition of PARC’s Gypsy; Lisa Project, a project manager; Lisa Calc, a spreadsheet; Lisa List, a database; and Lisa Graph. From a very early date the team took the then-unusual step of getting constant feedback on the interface from ordinary people. When the time came to conduct another round of testing, they would go to Apple’s Human Resources department and request a few new hires from the clerical pool or the like who had not yet been exposed to Lisa. Tesler:

We had a couple of real beauties where the users couldn’t use any of the versions that were given to them and they would immediately say, “Why don’t you just do it this way?” and that was obviously the way to do it. So sometimes we got the ideas from our user tests, and as soon as we heard the idea we all thought, “Why didn’t we think of that?” Then we did it that way.

It’s difficult to state strongly enough what a revolutionary change this made from the way that software had been developed before, in which a programmer’s notion of utilitarian functionality was preeminent. It was through this process that the team’s most obvious addition to the PARC template arose: pull-down menus. User testing also led them to decide to include just one button on the mouse, in contrast to the PARC mice which had three or more. While additional buttons could be useful for advanced users, new users found them intimidating. Thus was born Apple’s stubborn commitment to the single-button mouse, which persisted more than twenty years. The final major piece of the user-interface puzzle, of the GUI blueprint which we still know today, came in June of 1981 when the team first saw the Xerox Star. The desktop metaphor was so obviously right for the office of the future that they immediately adopted it. Thus the Lisa in its final form was an amalgam of ideas taken from PARC and from the Star, but also represents significant original research.

As 1982 began, the picture of what Lisa should be was largely complete. Now it just came down to finishing everything. As the year wore on, the milestones piled up. In February the system clipboard went in, allowing the user to cut and paste not just between the six bundled applications but presumably any that might be written in the future — a major part of the Lisa vision of a unified, consistent computing environment. On July 30, 1982, the team started all six applications at once on a single computer to test the capabilities of the advanced, multitasking operating system. On September 1, the Lisa was declared feature complete; all that remained now was to swat the bugs. On October 10, it was demonstrated to Apple’s sales force for the first time.

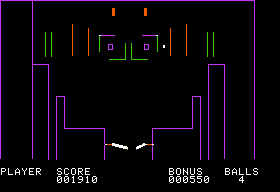

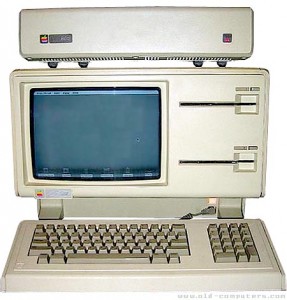

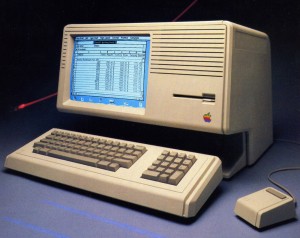

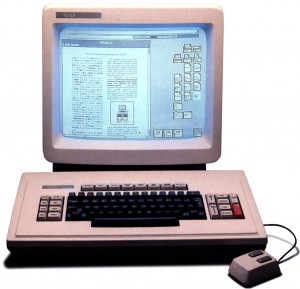

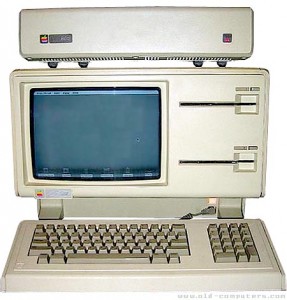

The Apple Lisa. Note the two Twiggy drives to the right. The 5 MB hard drive sits on top.

John Couch’s people had a lot to show off. The Lisa’s hardware was quite impressive, with its high-resolution bitmapped display, its mouse, and its astonishing 1 full MB of memory. (To understand just how huge that number was in 1982, consider that the IBM PC had not been designed to even support more than 640 K, a figure IBM regarded as a strictly theoretical upper limit no one was ever likely to reach in the real world.) Yet it was the software that was the most impressive part. To use an overworked phrase that in this case is actually deserved, Lisa OS was years ahead of its time. Aside from only the hacker-oriented OS-9, it was the first on a PC to support multitasking. If the user started up enough programs to exceed even the machine’s 1 MB of memory, a virtual-memory scheme kicked in to cache the excess onto the 5 MB hard drive. (By way of comparison, consider that this level of sophistication would not come to a Microsoft operating system until Windows 3.0, released in 1990.) It was possible to cut and paste data between applications effortlessly using the system clipboard. With its suite of sophisticated what-you-see-is-what-you-get applications that benefited greatly from all that end-user testing and a GUI desktop that went beyond even what had been seen on the Star (and arguably beyond anything that would be seen for the rest of the 1980s) in consistency and usability, the Lisa was kind of amazing. Apple confidently expected it to change the world, or at least to remake the face of computing, and in this case their hubris seemed justified.

Apple officially announced the Lisa on January 19, 1983, alongside the Apple IIe in an event it labeled “Evolution/Revolution.” (I trust you can guess which was which.) They managed to convince a grudging Jobs, still the face of the company, to present these two machines that he ardently hated in his heart of hearts. It must have especially cut because the introduction was essentially a celebration of the bet he was about to lose with Couch — that being that he could get his Macintosh out before the Lisa. Jobs had come to hate everything about the Lisa project since his dismissal. He saw the Lisa team, now over 200 people strong when the business and marketing arms were taken into account, as bloated and coddled, full of the sort of conservative, lazy HP plodders he loathed. That loathing extended to Couch himself, whose low-key style of “management by walking around” and whose insistence that his people work sane hours and be given time for a life outside of Apple contrasted markedly with the more high-strung Jobs.

But then, Jobs had much to be unhappy about at this point. Time magazine had planned to make him its “Man of the Year” for 1982, until their journalists, digging around for material for the feature, unearthed a series of rather unflattering revelations about Jobs’s personal life, his chequered, contentious career at Apple, and the hatred many even in his own company felt toward him. Prominent among the revelations were the first reports of the existence of Jobs’s daughter Lisa and Jobs’s shabby treatment of her and her mother. In the face of all this, Time turned the Jobs feature into an elegiac for a brilliant young man corrupted and isolated from his erstwhile friends by money and fame. (Those who had known Jobs before his “corruption” mostly just shrugged at such a Shakespearian portrayal and said, well, he’d always kind of been an asshole.) The Man of the Year feature, meanwhile, became the computer itself — a weird sort of “man,” but what was the alternative? Who else symbolized the face of the computer age to mainstream America better than Jobs? This snub rankled Jobs greatly. It didn’t make Apple any too happy either, as now their new wonder-computer was hopelessly ensnared with the tawdry details of Jobs’s personal life. They had discussed changing the name many times, to something like the Apple IV or — this was Trip Hawkins’s suggestion — the Apple One. But they had ended up keeping “Lisa” because it was catchy, friendly, and maybe even a little bit sexy, and separated the new machine clearly from both the Apple III fiasco and everything else that had come before from Apple. Now they wished they could change it, but, with advertising already printed and announcements made, there was nothing to be done. It was the first ominous sign of a launch that would end up going nothing like they had hoped and planned.

Still, as time rolled on toward June 1983, when the Lisa would actually start shipping, everything seemed to be going swimmingly. Helped along by ecstatic reviews that rightly saw the Lisa as a potentially revolutionary machine, Apple’s stock soared to $55 on the eve of the first shipments, up from $29 at the time of the Evolution/Revolution events. Partly this was down to the unexpectedly strong sales of the Apple IIe, which unlike the Lisa had gone into production immediately after its announcement, but mostly it was all about the sexier Lisa. Apple already had 12,000 orders in the queue before the first machine shipped.

But then, with the Lisa actually shipping at last, the orders suddenly stopped coming. Worse, many of those that had been already placed were cancelled or returned. Within the echo chamber inside Apple, Lisa had looked like a surefire winner, but that perception had depended upon ignoring a lot of serious problems with the computer itself, not to mention some harsh marketplace realities, in favor of the Lisa’s revolutionary qualities. Now the problems all started becoming clear.

Granted, some of the criticisms that now surfaced were hilariously off-base in light of a future that would prove the Lisa right about so many fundamentals. As always, some people just didn’t get what Lisa was about, were just too mired in the conventional wisdom. From a contemporary issue of Byte:

The mouse itself seems pointless; why replace a device you’re afraid the executive is afraid of (the keyboard) with another unfamiliar device? If Apple was seriously interested in the psychology involved it would have given said executive a light pen.

While the desktop-with-icons metaphor may be useful, were I a Fortune 500 company vice-president, I would be mortally insulted that a designer felt my computer had to show me a picture of a wastebasket to direct me to the delete-file function. Such offensive condescension shows up throughout the design, even in the hardware (e.g., labeling the disk release button “Disk Request”).

I’d hoped (apparently in vain) that Apple finally understood how badly its cutesy, whimsical image hurts its chances of executive-suite penetration. This image crops up in too many ways on the Lisa: the Apple (control) key, the mouse, and on and on. Please, guys, the next time you’re in the executive-suite waiting room, flip through the magazines on the table. You’ll find Fortune, Barron’s, Forbes, etc., but certainly not Nibble. There’s a lesson there.

Other criticisms, however, struck much closer to home. There was one in particular that came to virtually everyone’s lips as soon as they sat down in the front of a Lisa: it was slow. No matter how beautiful and friendly this new interface might look, actually using it required accepting windows that jerked reluctantly into place seconds after pulling on them with the mouse, a word processor that a moderately skilled typist could outrace by lines at a time, menus that drew themselves line by laborious line while you sat waiting and wondering if you were ever going to be able to just get this letter finished. Poor performance had been the dirty little secret plaguing GUI implementations for years. Certainly it had been no different on the Alto. One PARC staffer estimated that the Alto’s overall speed would have to be improved by a factor of ten for it to be a viable commercial product outside the friendly confines of PARC and its ultra-patient researchers. Apple only compounded the problem with a hardware design that was surprisingly clunky in one of its most vital areas. Bizarrely on a machine that was ultimately going to be noticed primarily for its display, they decided against adding any specialized chips to help generate said display, choosing instead to dump the entire burden onto the 68000. Apple would not even have needed to design its own custom display chip, a task that would have been difficult without the resources of, say, Commodore’s MOS Technologies subsidiary. Off-the-shelf solutions, like the NEC 7220, were available, but Apple chose not to avail themselves of them. To compound the problem still further, they throttled the Lisa’s 68000 back to 5 MHz from its maximum of 8 MHz to keep it in sync with the screen refreshes it needed to constantly perform. With the 68000 so overloaded and strangled, the Lisa could seem almost as unusably slow as the old Alto at many tasks.

Other problems that should have been obvious before the Lisa was released also cropped up. The machine used a new kind of floppy disk drive that Apple had been struggling with in-house since all the way back in 1978. Known as Twiggy informally, the disks had the same external dimensions as the industry-standard 5 1/4″ disks, but were of a new design that allowed greater capacity, speed, and (theoretically) reliability. Trouble was, the custom disks were expensive and hard to find (after all, only the Lisa used them), and the whole system never worked properly, requiring constant servicing. The fact that they were on the Lisa at all made little sense in light of the new 3.5″ “micro-floppy” standard just introduced by Sony. Those disks were reliable, inexpensive, and easily available, everything Twiggy was not, while matching or exceeding all of Twiggy’s other specifications. They were in fact so good that they would remain a computer-industry staple for the next twenty years. But Apple had poured millions into the Twiggy boondoggle during the previous several years of constant internal confusion, and they were determined to use it.

And then there was the price. Trip Hawkins’s marketing-requirements document from back in 1980 had presciently warned that the Lisa must be priced at less than $5000 to have a chance of making an impact. Somewhere along the way, however, that bit of wisdom had been lost. The Lisa debuted at no less than $10,000, a figure that in 1983 dollars could buy you a pretty nice new car. Given its extreme price and the resulting necessity that it be marketed exclusively to big corporate customers, it’s tough to say whether the Lisa can really be considered a PC in the mold of the Apple II and IBM PC at all. It utterly lacked the democratic hobbyist spirit that had made the Apple II such a success. Software could be written for the Lisa only by yoking two Lisas together, one to host the program being written and the other to be used for writing it with the aid of an expensive toolkit available only from Apple. It was a barrier to entry so high that the Lisa was practically a closed system like the Xerox Star, confined to running only the software that Apple provided. Indeed, if Lisa had come from a company not known exclusively as a PC maker — like, say, Xerox — perhaps Lisa would have been taken by the trade press as a workstation computer or an “office information system” in the vein of the Star. Yet the Lisa also came up short in several key areas in comparison to the only marginally more expensive Star. It lacked the Star’s networking support, meaning that a key element of PARC’s office of the future was missing. And it lacked a laser printer. In its stead Apple offered a dot-matrix model it had jointly developed with C. Itoh. Like too much else about the Lisa, it turned out slow, clunky, and unreliable; documents on paper were always a disappointment after viewing them on the Lisa’s crisp screen. Any office manager willing to spend the cash for the Lisa might very well have been better off splashing out some extra for the Star (not that many people were buying either system).

Finally, there was the Macintosh problem. Thanks to their internal confusion and the engine of chaos that was Steve Jobs, Apple had two 68000-based computers sporting mice, GUI-based operating systems, and high-resolution bitmapped monochrome displays. Best of all, the two computers were completely incompatible with each other. Seeing his opportunity, Jobs started leaking like a sieve about Apple’s next computer even as he dutifully demonstrated the Lisa. Virtually every preview or review thus concluded with a mention of the rumors about something called “Mackintosh,” which promised to do just about everything Lisa did for a fraction of the price. Apple’s worst enemy could hardly have come up with a better scheme to squelch the Lisa’s sales.

The rest of the Lisa story is largely that of an increasingly desperate Apple struggling to breathe life back into her. In September they dropped the price to $8200, or $7000 for just the machine and the opportunity to order the applications à la carte rather than as a mandatory bundle. By now Apple’s shares had dropped back to $27, less than they had been to start the year. At year’s end they had sold just 15,000 Lisas, down from estimates of 50,000 in those heady days of June.

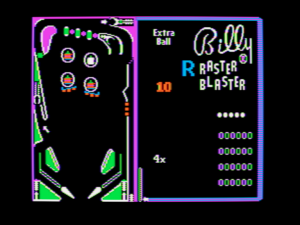

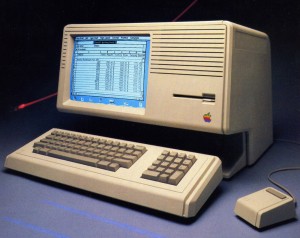

Lisa 2. The Twiggy drives have been replaced by a single 3.5″ drive, and the hard drive is now internal.

In January of 1984 Apple released a much-needed revised model, Lisa 2, which replaced the Twiggy drives with 3.5″ models. Price was now in the range of $4000 to $5500. But Macintosh, now also released at last, well and truly stole the Lisa’s thunder yet again. The last of the Lisas were repackaged with a layer of emulation software as the Macintosh XL in January of 1985, marking the end of the Lisa nameplate. Sales actually picked up considerably after this move, as the price dropped again and the XL was still more advanced in many ways than the current “real” Macintosh. Still, the XL marked the end of the line for Lisa technology; the XL was officially discontinued on April 29, 1985, just less than two years after the first Lisa had rolled off the production line. In the end Apple sold no more than 60,000 Lisas and Macintosh XLs in total.

The Lisa was in many ways half-baked, and its commercial fate, at least in hindsight, is perfectly understandable. Yet its soft power was immense. It showed that a sophisticated, multitasking operating system could be done on a microcomputer, as could a full GUI. The latter achievement in particular would have immediate repercussions. While it would still be years before most average users would have machines built entirely around the PARC/Lisa model of computing, there was much about the Lisa that was implementable even on the modest 8-bit machines that would remain the norm in homes for years to come. Lisa showed that software could be more visual, easier to use, friendlier even on those machines. That new attitude would begin to take root, and nowhere more so than in the ostensible main subject of this blog which I’ve been neglecting horribly lately: games. We’ll begin to see how the Lisa way trickled down to the masses in my next article, which I promise will be about games again at last.

On December 14, 1989, Xerox finally got around to suing Apple for allegedly ripping off their PARC innovations, thus prompting the joke that Xerox can’t even sue you on time. With the cat so well and thoroughly out of the bag by this point, the suit was dismissed a few months later.

(As with most aspects of Apple history, there’s enough material available on the Lisa project in print and on the Internet for days of reading. A particularly fascinating source, because it consists entirely of primary-source documents, is the Lisa directory on Asimov.net.)