As I described in my last article, many people were beginning to feel that change was in the air as they observed the field of videogame consoles and the emerging market for home computers during the middle part of 1982. If a full-fledged computer was to take the place of the Atari VCS in the hearts of America’s youth, which of the plethora of available machines would it be? IBM had confidently expected theirs to become the one platform to rule them all, but the IBM PC was not gaining the same traction in the home that it was enjoying in business, thanks to an extremely high price and lackluster graphics. Apple was still the media darling, but the only logical contender they could offer for the segment, the Apple II Plus, was looking increasingly aged. Its graphics capabilities, so remarkable for existing at all back in 1977, had barely been upgraded since, and weren’t really up to the sort of colorful action games the kids demanded. Nor was its relatively high price doing it any favors. Another contender was the Atari 400/800 line. Although introduced back in late 1979, these machines still had amongst the best graphics and sound capabilities on the market. On the other hand, the 400 model, with its horrid membrane keyboard, was cost-reduced almost to the point of unusability, while the 800 was, once again, just a tad on the expensive side. And Atari itself, still riding the tidal wave that was the VCS, showed little obvious interest in improving or promoting this tiny chunk of its business. Then of course there was Radio Shack, but no one — including them — seemed to know just what they were trying to accomplish with a pile of incompatible machines of wildly different specifications and prices all labeled “TRS-80.” And there was the Commodore VIC-20 which had validated for many people the whole category of home computer in the first place. Its price was certainly right, but it was just too limited to have long legs.

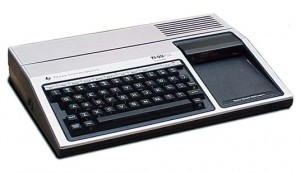

The most obvious contender came from an unexpected quarter. Back in early 1980, the electronics giant Texas Instruments had released a microcomputer called the TI-99/4. Built around a CPU of TI’s own design, it was actually the first 16-bit machine to hit the market. It had a lot of potential, but also a lot of flaws and oddities to go with its expensive price, and went nowhere. Over a year later, in June of 1981, TI tried again with an updated version, the TI-99/4A. The new model had just 16 K of RAM, but TI claimed more was not necessary. Instead of using cassettes or floppy disks, they sold software on cartridges, a technique they called “Solid State Software.” Since the programs would reside in the ROM of the cartridge, they didn’t need to be loaded into RAM; that needed to be used only for the data the programs manipulated. The idea had some real advantages. Programs loaded instantly and reliably, something that couldn’t be said for many other storage techniques, and left the user to fiddle with fragile tapes or disks only to load and save her data files. This just felt more like the way a consumer-electronics device ought to work to many people — no typing arcane commands and then waiting and hoping, just pop a cartridge in and turn the thing on. The TI-99/4A also had spectacularly good graphics, featuring sprites, little objects that were independent of the rest of the screen and could be moved about with very little effort on the part of the computer or its programmer. They were ideal for implementing action games; in a game of Pac-Man, for instance, the title character and each of the ghosts would be implemented as a sprite. Of the other contenders, only the Atari 400 and 800 offered sprites — as well as, tellingly, all of the game consoles. Indeed, they were considered something of a necessity for a really first-rate gaming system. With these virtues plus a list price of just $525, the TI-99/4A was a major hit right out of the gate, selling in numbers to rival the even cheaper but much less capable VIC-20. It would peak at the end of 1982 with a rather extraordinary (if brief-lived) 35 percent market share, and would eventually sell in the neighborhood of 2.5 million units.

With the TI-99/4A so hot that summer of 1982, the one wildcard — the one obstacle to anointing it the king of home computers — was a new machine just about to ship from Commodore. It was called the Commodore 64, and it would change everything. Its story had begun the previous year with a pair of chips.

In January of 1981 some of the engineers at Commodore’s chipmaking subsidiary, MOS Technologies, found themselves without a whole lot to do. The PET line had no major advancements in the immediate offing, and the VIC-20’s design was complete (and already released in Japan, for that matter). Ideally they would have been working on a 16-bit replacement for the 6502, but Jack Tramiel was uninterested in funding such an expensive and complicated project, a choice that stands as amongst the stupidest of a veritable encyclopedia of stupidity written by Commodore management over the company’s chaotic life. With that idea a nonstarter, the engineers hit upon a more modest project: to design a new set of graphics and sound chips that would dramatically exceed the capabilities of the VIC-20 and (ideally) anything else on the market. Al Charpentier would make a graphics chips to be called the VIC-II, the successor to the VIC chip that gave the VIC-20 its name. Bob Yannes would make a sound synthesizer on a chip, the Sound Interface Device (SID). They took the idea to Tramiel, who gave them permission to go ahead, as long as they didn’t spend too much.

In deciding what the VIC-II should be, Charpentier looked at the graphics capabilities of all of the computers and game machines currently available, settling on three as the most impressive, and thus the ones critical to meet or exceed: the Atari 400 and 800, the Mattel Intellivision console, and the soon-to-be-released TI-99/4A. Like all of these machines, the VIC-II chip would have to have sprites. In fact, Charpentier spent the bulk of his time on them, coming up with a very impressive design that allowed up to eight onscreen sprites in multiple colors. (Actually, as with so many features of the VIC-II and the SID, this was only the beginning. Clever programmers would quickly come up with ways to reuse the same sprite objects, thus getting even more moving objects on the screen.) For the display behind the sprites, Charpentier created a variety of character-based and bitmapped modes, with palettes of up to 16 colors at resolutions of up to 320 X 200. On balance, the final design did indeed exceed or at least match the aggregate capabilities of anything else on the market. It offered fewer colors than the Atari’s 128, for example, but a much better sprite system; fewer total sprites (without trickery) than the TI-99/4A’s 32, but bigger and more colorful ones, and with about the same background display capabilities.

If the VIC-II was an evolutionary step for Commodore, the SID was a revolution in PC and videogame sound. Bob Yannes, just 24 years old, had been fascinated by electronic sound for much of his life, devouring early electronica records like those by Kraftwerk and building simple analog synthesizers from kits in his garage. Hired by MOS right out of university in 1978, he felt like he had been waiting all his employment for just this project. An amateur musician himself, he was appalled by the sound chips that other engineers thought exceptional, like that in the Atari 400 and 800. From a 1985 IEEE Spectrum article on the making of the Commodore 64:

The major differences between his chip and the typical videogame sound chips, Yannes explained, were its more precise frequency control and its independent envelope generators for shaping the intensity of a sound. “With most of the sound effects in games, there is either full volume or no volume at all. That really makes music impossible. There’s no way to simulate the sound of any instrument even vaguely with that kind of envelope, except maybe an organ.”

Although it is theoretically possible to use the volume controls on other sound chips to shape the envelope of a sound, very few programmers had ever tackled such a complex task. To make sound shaping easy, Yannes put the envelope controls in hardware: one register for each voice to determine how quickly a sound builds up; two to determine the level at which the note is sustained and how fast it reaches that level; and one to determine how fast the note dies away. “It took a long time for people to understand this,” he conceded.

But programmers would come to understand it in the end, and the result would be a whole new dimension to games and computer art. The SID was indeed nothing short of a full-fledged synthesizer on a chip. With three independent voices to hand, its capabilities in the hands of the skilled are amazing; the best SID compositions still sound great today. Games had beeped and exploded and occasionally even talked for years. Now, however, the emotional palette game designers had to paint on would expand dramatically. The SID would let them express deep emotions through sound and (especially) music, from stately glory to the pangs of romantic love, from joy to grief.

In November of 1981 the MOS engineers brought their two chips, completed at last, to Tramiel to find out what he’d like to do with them. He decided that they should put them into a successor to the VIC-20, to be tentatively titled the VIC-40. In the midst of this discussion, it emerged that the MOS engineers had one more trick up their sleeves: a new variant of the 6502 called the 6510 which offered an easy way to build an 8-bit computer with more than 48 K of RAM by using a technique called bank switching.

Let’s stop here for just a moment to consider why this should have been an issue at all. Both the Zilog Z80 and the MOS 6502 CPUs that predominated among early PCs are 8-bit chips with 16-bit address buses. The latter number is the one that concerns us right now; it means that the CPU is capable of addressing up to 64 K of memory. So why the 48 K restriction? you might be asking. Well, you have to remember that a computer does not only address RAM; there is also the need for ROM. In the 8-bit machines, the ROM usually contains a BASIC-based operating environment along with a few other essentials like the glyphs used to form characters on the screen. All of this usually consumes about 16 K, leaving 48 K of the CPU’s address space to be mapped to RAM. With the arrival of the 48 K Apple II Plus in 1979, the industry largely settled on this as both the practical limit for a Z80- or 6502-based machine and the configuration that marked a really serious, capable PC. There were some outliers, such as Apple’s Language Card that let a II Plus be expanded to 64 K of RAM by dumping BASIC entirely in lieu of a Pascal environment loaded from disk, but the 48 K limit was largely accepted as just a fact of life for most applications.

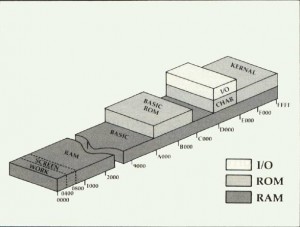

With the 6510, however, the MOS engineers added some circuitry to the 6502 to make it easy to swap pieces of the address space between two (or more) alternatives. Below is an illustration of the memory of the eventual Commodore 64.

Ignoring the I/O block as out of scope for this little exercise, let’s walk through this. First we have 1 K of RAM used as a working space to hold temporary values and the like (i.e., the program stack). Then 1 K is devoted to storing the current contents of the screen. Next comes the biggest chunk, 38 K for actual BASIC programs. Then 8 K of ROM, which stores the BASIC language itself. Then comes another 4 K of “high RAM” that’s gotten trapped behind the BASIC ROM; this is normally inaccessible to the BASIC programmer unless she knows some advanced techniques to get at it. Then 4 K of ROM to hold the glyphs for the standard onscreen character set. Finally, 8 K of kernel, storing routines for essential functions like reading the keyboard or interacting with cassette or disk drives. All of this would seem to add up to a 44 K RAM system, with only 40 K of it easily accessible. But notice that each piece of ROM has RAM “underneath” it. Thanks to the special circuitry on the 6510, a programmer can swap RAM for ROM if she likes. Programming in assembly language rather than BASIC? Swap out the BASIC ROM, and get another 8 K of RAM, plus easy, contiguous access to that high block of another 4 K. Working with graphics instead of words, or would prefer to define your own font? Swap out the character ROM. Taking over the machine entirely, and thus not making so much use of the built-in kernel routines? Swap the kernel for another 8 K of RAM, and maybe just swap it back in from time to time when you want to actually use something there.

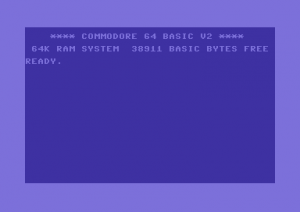

The above will hopefully answer the most common first question of a new Commodore 64 user, past or present: Why does my “64 K RAM system” say it has only 38 K free for BASIC? The rest of the memory is there, but only for those who know how to get at it and who are willing to forgo the conveniences of BASIC. I should emphasize here that the concept of bank switching was hardly an invention of the MOS engineers; it’s a fairly obvious approach, after all. Apple had already used the technique to pack a full 128 K of RAM into a 6502-based computer of their own, the failed Apple III (about which more in the very near future). The Apple III, however, was an expensive machine targeted at businesses and professionals. The Commodore 64 was the first to bring the technique to the ordinary consumer market. Soon it would be everywhere, giving the venerable 6502 and Z80 new leases on life.

Jack Tramiel wasn’t a terribly technical fellow, and likely didn’t entirely understand what an extra 16 K of memory would be good for in the first place. But he knew a marketing coup when he saw one. Thus the specifications of the new machine were set: a 64 K system built around MOS’s three recent innovations — the 6510, the VIC-II, and the SID. The result should be cheap enough to produce that Commodore could sell it for less than $600. Oh, and please have a prototype ready for the January 1982 Winter CES show, less than two months away.

With so little time and such harsh restrictions on production costs, Charpentier, Yannes, and the rest of their team put together the most minimalist design they could to bind those essential components together. They even managed to get enough of it done to have something to show at Winter CES, where the “VIC-40” was greeted with excitement on the show floor but polite skepticism in the press. Commodore, you see, had a well-earned reputation, dating from the days when the PET was the first of the trinity of 1977 to be announced and shown but the last to actually ship, for over-promising at events like these and delivering late or not at all. Yet when Commodore showed the machine again in June at the Summer CES — much more polished, renamed the Commodore 64 to emphasize what Tramiel and Commodore’s marketing department saw as its trump card, and still promised for less than $600 — they had to start paying major attention. Days later it started shipping. The new machine was virtually indistinguishable from the VIC-20 in external appearance because Commodore hadn’t been willing to spend the time or money to design a new case.

Inside it was one hell of a machine for the money, although not without its share of flaws that a little more time, money, and attention to detail during the design process could have easily corrected.

The BASIC housed in its ROM (“BASIC 2.0”) was painfully antiquated. It was actually the same BASIC that Tramiel had bought from Microsoft for the original PET back in 1977. Bill Gates, in a rare display of naivete, sold him the software outright for a flat fee of $10,000, figuring Commodore would have to come back soon for another, better version. He obviously didn’t know Jack Tramiel very well. Ironically, Commodore did have on hand a better BASIC 4.0 they had used in some of the later PET models, but Tramiel nixed using it in the Commodore 64 because it would require a more expensive 16 K rather than 8 K of ROM chips to house. People were already getting a lot for their money, he reasoned. Why should they expect a decent BASIC as well? The Commodore 64’s BASIC was not only primitive, but completely lacked commands to actually harness the machine’s groundbreaking audiovisual capabilities; graphics and sound could be accomplished in BASIC only by using “peek” and “poke” commands to access registers and memory locations directly, an extremely awkward, inefficient, and ugly way of programming. If the memory restrictions on BASIC weren’t enough to convince would-be game programmers to learn assembly language, this certainly did. The Commodore 64’s horrendous BASIC likely accelerated an already ongoing flight from the language amongst commercial game developers. For the rest of the 1980s, game development and assembly language would go hand in hand.

Due to a whole combination of factors — including miscommunication among marketing, engineering, and manufacturing, an ultimately pointless desire to be hardware compatible with the VIC-20, component problems, cost-cutting, and the sheer rush of putting a product together in such a limited time frame — the Commodore 64 ended up saddled with a disk system that would become, even more than the primitive BASIC, the albatross around the platform’s neck. It’s easily the slowest floppy-disk system ever sold commercially, on the order of thirty times slower than Steve Wozniak’s masterpiece, the Apple II’s Disk II system. Interacting with disks from BASIC 2.0, which was written before disk drives existed on PCs, requires almost as much patience as does waiting for a program to load. For instance, you have to type “LOAD ‘$’, 8” followed by ‘LIST’ just to get a directory listing. As an added bonus, doing so wipes out any BASIC program you might have happened to have in memory.

The disk system’s flaws frustrate because they dissipate a lot of potential strengths. Commodore had had a unique approach to disk drives ever since producing their first for the PET line circa 1979. A Commodore disk drive is a smart device, containing its own 6502 CPU as well as ROM and 2 K of RAM. The DOS used on other computers like the Apple II to tell the computer how to control the drive, manage the filesystem, etc., is unnecessary on a Commodore machine. The drive can control itself very well, thank you very much; it already knows all about that stuff. This brings some notable advantages. No separate DOS has to be loaded into the computer’s RAM, eating precious memory. DOS 3.3, for example, the standard on the Apple II Plus at the time of the Commodore 64’s introduction, eats up more than 10 K of the machine’s precious 48 K of RAM. Thus the Commodore 64’s memory edge was in practical terms even more significant than it appeared on paper. Because it’s possible to write small programs for the drive’s CPU to process and load them into the drive’s RAM, the whole system was a delight for hackers. One favorite trick was to load a disk-copying program into a pair of drives, then physically disconnect them from the computer. They would continue happily copying disks on their own, as long as the user kept putting more disks in. More practically for average users, it was often possible for games to play music or display animated graphics while simultaneously loading from the drive. Other computers’ CPU were usually too busy controlling the drive to manage this. Of course, this was a very good feature for this particular computer, because Commodore 64 users would be spending a whole lot more time than users of other computers waiting for their disk drives to load their programs.

Quality-control issues plagued the entire Commodore 64 line, especially in the first couple of years. One early reviewer had to return two machines before Commodore shipped him one that worked; some early shipments to stores were allegedly 80 percent dead on arrival. To go with all of their other problems, the disk drives were particularly unreliable. In one early issue, Compute!’s Gazette magazine stated that four of the seven drives in their offices were currently dead. The poor BASIC and unfriendly operating environment, the atrocious disk system, and the quality-control issues, combined with no option for getting the 80-column display considered essential for word processing and much other business software, kept the Commodore 64 from being considered seriously by most businesses as an alternative to the Apple II or IBM PC. Third-party solutions did address many of the problems. Various improved BASICs were released as plug-in cartridges, and various companies rewrote the systems software to improve transfer speeds by a factor of six or more. But businesses wanted machines that just worked for them out of the box, which Apple and IBM largely gave them while Commodore did not.

None of that mattered much to Commodore, at least for now, because they were soon selling all of the Commodore 64s they could make for use in homes. No, it wasn’t a perfect machine, not even with its low price (and dropping virtually by the month), its luxurious 64 K of memory, its versatile graphics, and its marvelous SID chip. But, like the Sinclair Spectrum that was debuting almost simultaneously in Britain, it was the perfect machine for this historical moment. Also like the Spectrum, it heralded a new era in its home country, where people would play — and make — games in numbers that dwarfed what had come before. For a few brief years, the premiere mainstream gaming platform in the United States would be a full-fledged computer rather than a console — the only time, before or since, that that has happened. We’ll talk more about the process that led there next time.

(As you might expect, much of this article is drawn from Brian Bagnall’s essential history of Commodore. The IEEE Spectrum article referenced above was also a gold mine.)