Let’s say that it’s the mid-1970s, and that you’re an early fan of Dungeons and Dragons, still a tiny offshoot of the niche hobby that is wargaming. Let’s further say that you have regular access to a computer at your place of education or work, and that you know how to program it. It might seem absurd to imagine a substantial overlap between the tiny number of people playing D&D circa 1975 and the decidedly limited if not quite so minuscule number who had access to a computer at that time, but in fact Will Crowther was hardly an anomaly; there was an inordinate number of hackers among early fans of the game. We can assume that hackers’ love of complex systems brought them to the game, just as it drew them to fantasy and science-fiction literature such as the works of Tolkien, where character and plot were subservient to (or at least equal in importance with) world-building.

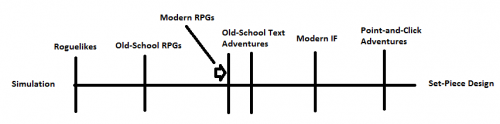

So, we have a substantial number of hackers entranced with D&D. Hackers being hackers, it’s not difficult to guess what happened next: various projects got under way to bring the experience of D&D to the computer. This was a task for which, depending on how you looked at it and to whom you talked, the computer was either ideally suited for or woefully unequipped to handle. We’ll take the best-case scenario first.

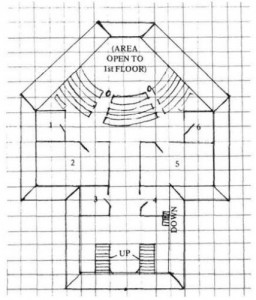

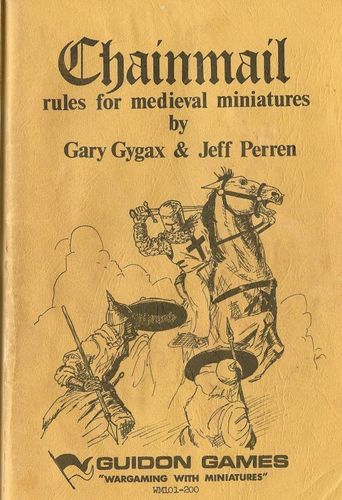

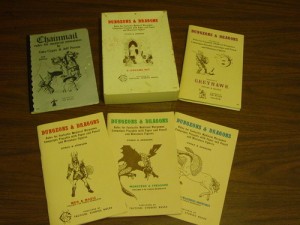

D&D was complicated. Even the original 1974 rules, which virtually everyone agreed were crude and sketchy in many areas, filled three separate booklets of about 35 pages each while recommending that the players also have on hand a copy of Gygax’s earlier Chainmail rules. But that was only the beginning. Just the core of Advanced Dungeons and Dragons, the definitive rules for the hardcore which TSR rolled out over the last three years of the 1970s, ran to hundreds of pages housed in three big, close-typed, hardcover volumes. To this ample base were added layer after layer of further embellishment via yet more hardcover volumes and an endless stream of Dragon magazine articles. It’s fair to say that a certain subset of D&D players — those who took after Gygax himself — absolutely reveled in all of this minutiae. Indeed, for some players the baroqueness of the whole endeavor was the major part of its appeal. Plenty of others, though, were like Arneson, in it for the visceral thrill of lived (if imaginary) experience. When they mustered their last bit of carefully hoarded mana to cast Cone of Cold, their last memorized spell, on the Lizard King (apologies to Jim Morrison), these players did not want to spend ten minutes cross-referencing manuals, calculating probabilities, and pondering such unsolvable existential conundrums as just why the hell an armor class of -5 was vastly better than an armor class of 10. They just wanted to know whether their spell sputtered and died, taking with it their party’s last hope, or whether the Lizard King had been turned into a giant green popsicle. Computers were pretty good at crunching numbers, and happy to apply even the most obtuse of rules to them. What if all of those tedious bits could be stuck into the computer, programmed and tinkered with by the Gygax-types of the world who enjoyed such things, leaving the Arnesons of the world free to just play? As an added bonus, the use of a computer might mean they could play all alone on their own time if they wanted to, rather than needing to assemble four or five friends. It seemed like a dream come true.

But wait a minute, said the naysayers (a group which included, ironically, many of the most committed Arnesons). One of the major things that defined D&D as different from any game that had come before was the sheer scope of possibility it offered to its players. A player was free, theoretically at least, to do absolutely anything she wanted to at any time. It was then up to the DM to find the rule he felt applied best from the small library he had lugged with him to the session. Failing that, he had to use his judgment to make up something appropriate on the spot. (We could note at this point that all of those rules TSR was constantly pumping out could never come to cover every conceivable situation anyway, and that there must come a point of diminishing returns where just making things up in such unusual circumstances was preferable to buying yet more rulebooks in the forlorn hope of covering all the bases, but let’s just let that go.) A computer, of course, can’t make judgment calls; it can only do what it’s been programmed to do. Further, it cannot appreciate the dashing rogue of a leather-clad thief with a severe aversion to wood elves (a case of childhood trauma) you have so creatively personified. It cannot craft an adventure into the heart of the forest just for you, during which Dirk Darkstone will have to confront his horror of effeminate green-clad men wielding bows. It can’t even provide you with Tasha Brightstone, the virtuous blonde paladin in the chainmail bikini torn between her desire for Dirk and the Code of the Virgin Warrior to which she has signed her name. Every computer program ever created, games included, must ultimately offer the user only the limited menu of possible actions anticipated by its designer. Whether that set consists of the up-and-down trackball motions of Pong or the various verbs a text-adventure designer has coded his game to recognize, this constraint is immutable. How then can a computer administer a game whose players can do literally anything? The gospel of tabletop D&D tells us that, even when presented with a tempting dungeon to plunder by the DM, the players are perfectly free to walk on past the Ominous Castle of the Mad Wizard Yordor and spend the evening trying to get a really good brawl started in the local tavern instead. So, the Arnesons of the world tell us, D&D and the computer are not such a marriage made in heaven. The computerized D&D player could avoid the Mad Wizard only by turning off the computer and doing something else, after all.

We’ve certainly hit upon a significant limitation, but let’s think about all this again before we go too much farther with that train of thought. I submit that in practice the players of D&D are restricted in their field of action, by social if not rules-derived constraints. How would you feel if you were that DM who had spent his entire weekend designing the Castle of the Mad Wizard Yordor, stocking it with fearsome monsters (but balanced to not be too much for the players to handle if they play it smart) and devious traps (but not so devious they cannot be disarmed most of the time by a thief of exactly the same level as Dirk Darkstone if he is cautious), only to have your players march on past the lot to go grope the local chicks in the pub? I’m guessing you’d consider the players a bunch of ungrateful bastards whom you’d just as soon not play with again. Thus, there is an implied social contract between DM and players, one in which the players, at least in the broad strokes, are expected to, well, do what is expected of them.

Further, I submit that the rhetoric of D&D as a form of improvisational storytelling and the reality of most player’s experience of the game were somewhat at odds. The AD&D Player’s Handbook tells us:

You interact with your fellow role players, not as Jim and Bob and Mary who work at the office together, but as Falstaff the fighter, Angore the cleric, and Filmar, the mistress of magic! The Dungeon Master will act the parts of “everyone else,” and will present to you a variety of new characters to talk with, drink with, gamble with, adventure with, and often fight with! Each of you will become an artful thespian as time goes by…

The “fight with” part of the extract above was the really important part to most players, the thing that defined the experience of D&D. TSR released at least a hundred adventure modules that had players descending into one thinly justified underground lair or another to kill things and take their stuff using the 23 pages of combat rules found in the Dungeon Master’s Guide alone, and exactly zero that principally involved talking, drinking, or gambling with new friends. Even Gygax seemed of two minds about the real point of D&D. For all the parallels he drew with Shakespeare and Aristotle, in practice he was a dungeon crawler all the way, dismissive of elaborate role-playing: “If I want to do that, I’ll join an amateur theater group.” I submit that D&D was in practice not mostly played by groups of “artful thespians,” but by scruffy teenage boys and men perfectly happy to remain Jim and Bob as they pondered the best way to kill that group of trolls in the next room. And that experience of D&D a computer could, within inevitable limits, simulate pretty well.