I closed my last article by noting that Ultimate Play the Game’s works can feel just a bit soulless to me with their slickness and unrelenting commercial focus — an opinion I’m sure many of you don’t share. Well, rest assured that I can’t attach any such complaint to my subject for today.

Automata UK was the creation of a pair of agitators named Mel Croucher and Christian Penfold who became the Merry Pranksters of the early British software industry, mixing absurdist humor with the DIY ethos of punk rock and more than a hint of an agitprop sensibility. Whatever else you care to say about them, you certainly can’t call them slick or commercial. Their works and their rhetoric harkened back to older utopian dreams for personal computing as a means to universal empowerment for all — dreams immersed in the ideals of the counterculture and promoted in the likes of the People’s Computer Company newsletter and the early issues of Creative Computing. With home computing taking off in Britain and the traditional forces of business and culture getting involved in a big way, those dreams were already beginning to sound quaint and anachronistic by the time Automata peaked in 1983 and 1984. Possessed as they were of about the level of business acumen you might expect from a pair of self-described “old hippies,” they were doomed from the start. Still, they had one hell of a lot of fun while they lasted.

Croucher was a disillusioned architect coming off a stint working under Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum to construct the modern Dubai. He’d also worked as a cartographer, played bass in rock bands, and briefly entertained the idea of becoming a painter. If Croucher was the would-be artist and visionary, Penfold was, relatively speaking, the more grounded; he’d sold everything from cars to plants to advertising space amidst various other jobs. Like many fruitful partnerships, they weren’t always sympatico with one another. Croucher declared that he was “to the left of Tony Benn” while Penfold was “to the right of Enoch Powell“: “That’s why it works — otherwise we’d come in in the morning and agree!”

Automata was founded circa 1977 on Croucher’s Dubai windfall. Like Melbourne House, it wasn’t initially conceived as a game or software developer, as is betrayed by the original full name: “Automata Cartography.” Capitalizing on Croucher’s background in cartography, they made tourist-friendly informational brochures and maps for the likes of the Sealink ferry service and British Airways. Those soon morphed into audio travel guides and promotions for foreign hotels as well as radio spots. Their guide to their home base of Portsmouth, narrated in the persona of, of all people, Charles Dickens, was heard by every tourist who booked a pleasure cruise around the harbor. They even produced some feature radio programming, such as a quiz program for Radio Victory that Penfold described as “rather like University Challenge without the brains.”

They were aboard a ferry on the English Channel, returning from working on a production for Sealink in the Channel Islands, when Croucher told Penfold about the Sinclair ZX81 computer he had just purchased, his first exposure to computing since the 1960s, when he’d struggled to teach the big machine at his university how to play “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” and flash its lights in rhythm. He’d seen advertisements for computer games in magazines for £4 or £5, a princely sum compared to what he and Penfold were used to getting paid for their work. And he recognized that the world stood on an artistic precipice.

I knew that computers were not for performing business functions at all, but would transform everything I was involved in. I was absolutely convinced that computers would facilitate the convergence of film, book, theatre and music, with the added miracle of interactivity.

Having learned from his struggles with ALGOL in earlier decades that he wasn’t much of a programmer, he asked Penfold if he’d like to take up the task, to implement his (Croucher’s) many ideas; Penfold seemed like he would have a better mind for the task. Penfold, as Croucher has delighted in telling interviewers ever since, promptly threw up — not in reaction to the idea, but because the crossing was rough and he was prone to seasickness. On that auspicious note, the new venture was born.

Options were of course decidedly limited on the ZX81 with its 1 K of memory. So Croucher and Penfold would put ten mini-games onto a cassette, each necessarily trivial in itself but building as a collection to address some overarching theme. Both reacted viscerally to violence in games even in this era when that meant no more than onscreen blobs knocking off other onscreen blobs. “If there is such a thing as an alien, it doesn’t want to come down to earth and get killed,” noted Croucher. “I have yet to find an arcade game where there is a full trial at the start,” rejoined Penfold. Croucher later put it even more strongly: “I think people who create violent games are lazy, ignorant, and have poodle shit for brains.” Thus Automata’s games from first to last would be resolutely nonviolent.

Yet that didn’t keep them from offending in other ways, as evidenced by their aptly named first tape, Can of Worms, with its “piss takes” (Croucher’s words) involving acne, vasectomies, Hitler, and Reagan, and featuring a Space Invaders satire along with Royal Flush, an anti-monarchy screed which, yes, does involve a toilet. It all seemed to Croucher the appropriate response to those combative early years of Thatcher’s reign, times of “repression, depression, recession, and political mayhem.” Some reviewers were predictably outraged, accusing Automata of “peddling pornography to kids” (exactly the sort of reaction, one senses, that Croucher and Penfold were hoping for). Others took it all more casually; Eric Deeson noted bemusedly in Your Computer that Can of Worms “must suffice for readers with bad taste until something more revolting appears.” Croucher and Penfold obligingly tried to up the ante with Love and Death, a progression from fertilization to death (a theme to which they would eventually return for their most famous work) and The Bible, always a subject guaranteed to enrage. All were storyboarded by Croucher and then programmed by Penfold in crude BASIC, which he bragged was like his poetry — “unstructured.”

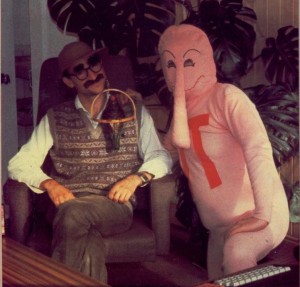

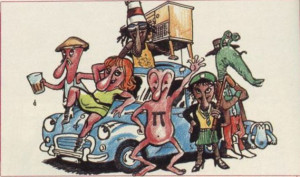

When the Spectrum appeared and sold like crazy, Automata, like most software houses, quickly made the switch to the new machine with its color graphics and luxurious 48 K of memory. They came into their own with their first game for the Speccy, the most commercially successful they would ever release. Pimania is an illustrated text adventure involving the Piman, a pink fellow with a grotesquely huge nose whose relationship to the player lives on some uncertain ground between ally and antagonist. Croucher had based him on a neighbor, “a deadpan poet with a great Scottish accent and peculiar vocal delivery.” He quickly became Automata’s mascot. Children took to calling the office wanting to speak to him; Croucher or Penfold obligingly played the part. He starred in a comic strip drawn by Robin Evans which ran on the back cover of every issue of Popular Computing Weekly. And he became a beloved presence at shows and other events, with Penfold usually inside the costume. Penfold:

He is an escape — an extension of our own personalities — all the nice and nasty bits rolled into one. But now he no longer just exists in our minds. He is real. He has his own character.

As for the game itself, the first puzzle tells you just about everything you need to know about what you’re in for. The opening screen simply says, “A key turns the lock,” then refuses to do anything else until you figure out that it wants you to press the Spectrum’s PI key. After that you get to work out that navigation is based not on the usual compass directions but the hands of a clock. And then things start to get difficult. Depending on how you look at it and how charitable you’re feeling, Pimania is either a surrealistic but tough-as-nails old-school adventure game, a confused and confusing and essentially unsolvable effort all too typical of beginning designers and programmers writing their first adventure, or a piece of sadistic satire sending up the absurdities of early adventure games.

Whatever its virtues or flaws, Pimania sold quite well, largely on the back of the Piman’s inexplicable popularity and a brilliant promotional idea. This was inspired by Kit Williams’s 1979 children’s book Masquerade, which encoded within it the location of a hare made out of gold and jewels and buried in a secret location somewhere in England. Thousands scoured the book for clues to the golden hare’s whereabouts until an intrepid seeker finally recovered it almost three years after publication. The book itself became a bestseller.

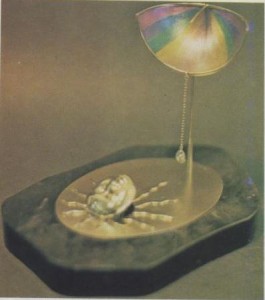

Croucher and Penfold commissioned De Beers Diamond International Award winner Barbara Tipple to make a Golden Sundial of Pi out of gold, lapis lazuli, obsidian, and diamond, at a claimed price of an extraordinary £6000. Winning Pimania would provide the clues as to where and, crucially, when to show up to claim the prize; only one day of the year would suffice.

Contests were quickly becoming de rigueur for almost every major adventure-game release in Britain, but few attracted the attention and passion of this one. And yet the Pimania mystery went unsolved, even though Penfold’s BASIC was an accessible target for would-be code divers. As months stretched into years, some began darkly hinting that maybe there wasn’t actually a Golden Sundial at all, that the whole thing was an elaborate practical joke being played on the gaming public — which admittedly would fit right into Automata’s public persona, but would also be unspeakably cruel. One poor fellow, convinced he’d cracked the code, even made plans to jet off to Bethlehem for Christmas. When Penfold and Croucher got wind of that, they were kind enough to tell him through the press that he was on the wrong track; I don’t know whether he believed them or went off anyway. The rather more accessible Stonehenge was a favorite target of many others, while yet more, having worked out a connection to Pegasus, visited seemingly everything everywhere having anything to do with horses. All for naught.

Even as the Pimania mystery remained unsolved, Automata launched a new contest to go with their next adventure, which bore the intimidating title of My Name is Uncle Groucho… You Win a Fat Cigar. As trippy as its predecessor, it had players chasing Groucho Marx — who now became Croucher’s alter ego to join Penfold in his Piman suit — around the United States. It was all surreal enough that it led interviewer Tristan Donovan recently to ask Croucher whether “drugs were a factor.” Croucher insists that he and Penfold were running on nothing stronger than beer and cigarettes.

This time the contest at least was a bit more conventional. The first player to identify a celebrity from clues provided in the game would win a trip to Hollywood on the Concorde and passage back home on the QE2. This one had an actual winner in relatively short order, one Phil Daley of Stoke-on-Trent. The celebrity in question, it turned out, was Mickey Mouse.

In addition to their own games, Croucher and Penfold also published quite a number of titles which they received from outside programmers. Each would be retrofitted into Automata’s ever-growing lore, which soon included a cast of characters largely drawn from the comic strip, with names like Ooncle Arthur, Swettibitz, and (my favorite) Lady Clair Sinclive. Each outside submission got an appropriately Automatatized new name, usually an awful pun: Pi-Balled, Pi-Eyed, Pi in the Sky. And each also got a theme song on the other side of the cassette, recorded on a little studio setup in Croucher’s front room. On these Croucher, who was something of a frustrated rock star, could run wild. The results are some weird amalgamation of musique concrète, New Wave synth-pop, a Monty Python sketch, and Croucher’s personal hero Frank Zappa. Or, for another set of comparisons: Your Computer called the track below (included with the Groucho game) “a curious fusion of a Mark Knopfler vocal and Depeche Mode backing, with a Bonzo Dog Band playout.”

And then came 1984 and Croucher’s magnum opus, Deus Ex Machina. He largely retired from Merry Prankstering for some six months to pour his heart and soul into it. He described it not as an Automata project proper but a “personal indulgence.” He believed he was creating Art, as well as the future of computerized entertainment:

I thought that by the mid-1980s ALL cutting-edge computer games would be like interactive movies, with proper structures, real characters, half-decent original stories, an acceptable soundtrack, a variety of user-defined narratives and variable outcomes. So I thought I’d better get in first, and produce the computer-game equivalent to Metropolis and Citizen Kane before the bastards started churning out dross. I wanted individuals to become totally immersed in the piece.

Penfold recognized Deus Ex Machina as “the crescendo of an idea” for Croucher, “an emotional achievement.”

Croucher had the idea of synchronizing a soundtrack to a computer game, to create an integrated, multimedia experience well before that word was in common usage. Because the Spectrum’s sound capabilities were rudimentary at best, the soundtrack would come on a separate cassette which the player must play at the same time as the game. The theme would be worthy of a prog-rock concept album: the journey of an individual through Shakespeare’s Seven Stages of Man in a vaguely dystopian postmodern world of mechanization, media saturation, and “Defect Police.” Perhaps it didn’t make a whole lot of literal sense — you’re somehow born from a dropping left behind by the last mouse on earth “as the nerve gas eased its sphincter” — but that hadn’t stopped Tommy or The Wall, had it?

The soundtrack, some 45 minutes in length, was mostly recorded by Croucher at home; he would have loved to have put a “half-decent band” together, but finances wouldn’t allow. He was, however, determined to get some well-known voices to feature on it, and to record them properly. He therefore booked precious time in a big London studio.

He recruited Frankie Howerd, an old-school showman and perennial on the British comedic circuit known if not always loved by everyone in Britain in the same way as a Rodney Dangerfield or Gallagher in the United States, to play the role of the head of the Defect Police, a “terrifying idiot.” (“It turned out that the real thing would eventually appear in the form of George W. Bush, but let’s not get into that.”) Howerd showed little understanding or interest in the project. He did his job — no more, no less.

More enthusiastic was former Doctor Who Jon Pertwee as the master of ceremonies. He angered everyone by arriving two hours late for his session, but explained that he’d fallen off his motorcycle on the way over and literally limped in as quickly as he could, bruised and still in leathers. All was forgiven, especially when he did a brilliant job. He and Croucher became fast friends, so much so that they later wrote a book together full of absurdist ramblings.

Croucher first wanted Patrick Moore, an eccentric popularizer of astronomy who was sort of the British Carl Sagan, complete with unforgettable tics that made him a television natural, to play the part of a sperm — “that would have been utterly surreal.” But when that fell through, he lucked into pub rocker Ian Dury of “Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick” fame. Dury “hated what mainstream games were offering kids,” and was excited to work on an alternative.

For the female voice of the machine, Dury recommended Marianne Faithfull, but she “was buried in drugs and we couldn’t get a meeting together.” After a bid for pop diva Hazel O’Connor also fell through, Croucher settled on a local singer named Donna Bailey, who wound up contributing the best singing on the soundtrack by far. The choir from nearby Warblington School also popped in to provide some “Another Brick in the Wall”-style vocals.

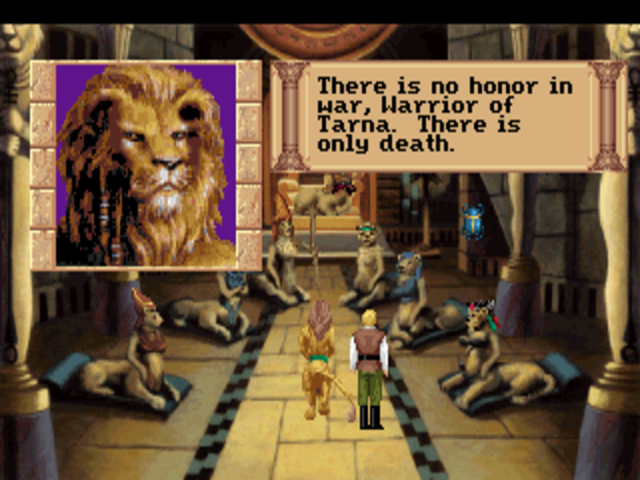

The game that accompanied all this was programmed to Croucher’s specifications by Andrew Stagg, a “boy genius” assembly coder he had discovered. It consists of a series of simple action games synchronized to the soundtrack. Your goal, such as it is, is to keep your “degree of ideal entity” as high as possible; each mistake in the games costs you percentage points. However, play continues inexorably onward no matter how badly you screw up, an obvious limitation of syncing a non-interactive soundtrack to an allegedly interactive experience. Then again, maybe that’s for the best: the games are not only of rather limited interest but also brutally difficult. I’ve never seen anyone get to the end with anything other than the worst possible score of 0%. For Croucher, the score wasn’t the point anyway:

The metaphor of the score is incidental, and I hoped people would interpret it to suit themselves. Do nothing — you’ll never win. Do everything right — you’ll feel good for a while, you’ll be regarded well according to society’s rules, but you’ll still never win. However, as the man [on the soundtrack] says — Imagine if this was nothing more than a computer game and we could start our lives all over again, and do it better. That was the only meaning really.

I have some problems with Deus Ex Machina and the rhetoric deployed around it, which we’ll get to momentarily, but when it works it can approach the total immersion Croucher was striving for, gameplay and music blending into a seamless whole. “The Lover” is a particular favorite, a gentle ballad, well sung by Bailey, that morphs into something more disturbing along with the game on the screen.

Despite good reviews by writers who admittedly weren’t entirely sure what to make of a piece of unabashed multimedia art sandwiched into their usual diet of Jet Set Willy and Manic Miner, despite being released just in time for the big Christmas buying season, sales were about as close to nonexistent as they could conceivably be. By February, some five months on from release, just 700 copies had been sold on the Spectrum; a more recent port to the Commodore 64 had sold all of twelve. Still, Deus Ex Machina won “Program of the Year” from the Computer Trade Association that February. But it was now, as a profile in Sinclair User from this period put it, “an angry, bitter world” for Automata, the easygoing insanity of Groucho and the Piman replaced by uglier sentiments. Penfold dropped all of the jokey pretensions at his acceptance speech to voice his opinion of the state of a changed industry in no uncertain terms.

He and Croucher blamed Deus Ex Machina‘s failure entirely on new systems of software distribution. When they had gotten into the business back in 1981, software was sold mostly via mail-order advertisements in the hobbyist magazines, with the remainder being sold directly to the handful of computer shops scattered around the country. This approach became untenable, however, when computers came to the High Street and the big vanilla chains like Boots and W.H. Smith got into the game. As in virtually every other retail industry, distributors stepped in to act as the middle men between the publishers and the final points of sale. With far more software being produced by 1984 than they could possibly handle, these could afford to be selective; indeed, they would say their survival depended upon it. They carefully evaluated each game sent to them to establish not only whether it was a reasonably professional, bug-free effort but also whether it had enough mass appeal to be worthy of precious shelf space. There was an inevitable power imbalance at play: small publishers, desperate to get their games onto shelves in what was turning into a very uncertain year, needed distributors more than distributors needed them. Thus the distributors could afford to drive hard bargains, demanding a 40 to 60 percent discount off retail price and a grace period of up to two months after delivery to pay the bill. They also wanted games to fit into one of three price points: £2 for older “classics” and newer discount titles; £6 for typical new games; £10 for big prestige releases like The Lords of Midnight or anything from the demigods over at Ultimate Play the Game.

Automata bucked every one of these demands. Not only did they continue to demand high margins and cash on delivery, but they insisted that Deus Ex Machina retail at a grandiose £15. They weren’t entirely alone; others fought the new world order and sometimes, at least temporarily, won. The most famous among them is Acornsoft, who insisted on a similarly high price point for Elite. When a number of distributors refused to carry the game, Acornsoft simply shrugged and sold to those who would, until Elite became a transformative hit and the recalcitrant distributors came back begging for Acornsoft’s business. The artsy, avant-garde Deus Ex Machina, however, obviously lacked the mass appeal of an Elite. This time it was mostly the distributors who shrugged and moved on, with a predictable impact on the game’s commercial fortunes.

Given these circumstances, Croucher was and is eager to attribute Deus Ex Machina‘s fate to the age-old struggle between art and commerce:

The corporates had taken over as they always will when they spot a new lucrative market. They wanted standard product. Deus was designed as non-standard and I got the market completely wrong.

I suppose that’s fair enough as far as it goes, even given the odd fact that Automata was in a death struggle to charge their customers more than the going rate. The thing is, though, the suits were kind of right in this instance. Taken as a one- or two-time experience, Deus Ex Machina is intriguing, even inspiring. As a game, however, it’s not up to much at all. It took a retrospective review in ACE magazine to finally acknowledge the obvious: “the actual gameplay was strictly humdrum.” Now, Croucher and others might respond, and not without justification, that to evaluate it the same way one evaluates a more traditional game is rather missing the point; Deus Ex Machina is more multimedia experience than game. Fair enough. Except that it’s hard to overlook the fact that players were being asked to pay £15 for the privilege, one hell of a lot of money in 1984 Britain. For that price — or, for that matter, for £10 or £6 or even £2 — they deserved more than an hour or two of entertainment. Deus Ex Machina‘s failure to find a market was indeed a failure of distribution. Yet it’s not one that can really be blamed on the distributors; again, that’s just the way that the retail business works, whether you’re selling shoes, books, or computer software. It wasn’t their fault that there was no practical way to get shorter-form works to the public for a price that wouldn’t leave them feeling ripped off. The distributors just recognized, probably rightly, that there was no practical place for Deus Ex Machina in the software industry of 1984. Such is the curse of the visionary.

Automata never recovered commercially or psychologically from the failure of Deus Ex Machina. The old spirit of anarchic fun became one of passive-aggressive petulance. “Automata’s next product will be something truly wonderful, but we’re just not going to release it until everybody pulls their socks up,” Penfold declared. “Automata are too good for this industry.”

Croucher walked away in mid-1985. Penfold at first did the expected, declaring his intention to struggle on, but Croucher’s departure marked the effective end to Automata as a going concern. Penfold dropped out of sight, while Croucher continued his career as (in Jaroslav Švelch’s words) a “perpetually failed visionary.” He designed another avant-garde game or two for other publishers; tried and failed to launch a multimedia game console that would combine laser-disc video with traditional computer graphics; wrote a linked series of comic fantasy adventures of one Tamara Knight for Crash magazine; wrote a column for Computer Shopper; designed a game and a viral-marketing campaign for Duracell; did God knows what all inside and outside the computer industry.

Deus Ex Machina has become a minor cause célèbre of academics and advocates for games as art, who tend to overrate it somewhat; it’s certainly interesting, certainly visionary, but hardly a deathless masterpiece. It’s simply the best that could be done by these people with these resources at this time — and there’s no shame in that. Much the same could be said about the rest of Automata’s works. They’re great to talk about, but too crude to be all that engaging to play today. Automata embraced a punk-rock ethos of production, but failed to recognize that games have in some senses a higher bar to clear. A bit of hiss on a record may be discountable, even charming, but a game with similar technical flaws is simply excruciating to play; it’s right here that comparisons between independent games and independent music break down horribly. Appropriately enough for what often seemed more an exercise in performance art than a real software company, Automata’s crazy catalog of subversive games is most fascinating simply because it existed at all.

But before Automata leaves the stage and I end this article, there’s one more piece of the story to tell. On July 22, 1985, Sue Cooper and Lizi Newman, a schoolteacher and music-shop proprietor respectively from Yorkshire, arrived at an odd local landmark on the Sussex Downs: a gigantic horse cut into a chalk hill. They stood at the horse’s mouth in a driving rain, looking around nervously. Then the Piman clambered out from behind a clump of bushes. He presented the ladies with their prize while Croucher played his theme song one last time. Automata had played fair after all; the Golden Sundial of Pi was real. Perhaps due to the fact that Automata was winding down and they were tired of spending their July 22s crouching in the Sussex mud, they had even shown the women a bit of mercy: they really should have been standing at the horse’s arse.

(If you’d like to experience Deus Ex Machina for yourself — and despite my reservations it’s well worth the effort — I’ve prepared a care package with the Spectrum tape image, the soundtrack as MP3 files, and the manual. Both sides of the tape are in the same tape image. The emulator should automatically load in the second side when the time comes, leaving you only to start the second soundtrack. That how it works under Fuse, anyway.

Information and art for this article were drawn from the following magazines: Your Spectrum of December 1984; Popular Computing Weekly of June 30 1983, January 12 1984, April 4 1985, November 28 1985; Home Computing Weekly of July 19 1983, December 13 1983, February 26 1985; Computer and Video Games of November 1982, December 1982, January 1984, October 1985, September 1986; Crash of February 1984, May 1985, April 1986; Big K of December 1984; Sinclair User of September 1984, February 1985, April 1985; Your Computer of February 1982, December 1983; ACE of May 1988; Computer Choice of January 1984. Also invaluable were ZX Golden Years, the new Automata website, the Deus Ex Machina 2 website, and the Piman Files. The last includes all of the Automata songs as MP3 files, including the one I’ve sampled here.)