The canon of Access Software is crazily varied in light of its relatively modest size. It begins with a utility and then proceeds through a series of frenetic action games of sometimes questionable taste, only to do an abrupt about-face and embrace that most staid of sports, golf. That long line of simulations is then joined by a series of gloriously cheesy full-motion-video adventure games. The variety is even more remarkable when you consider that the output of this modest company is largely derived from the minds of just three men: brothers Bruce and Roger Carver and one Chris Jones, instantly recognizable to adventure-game fans as the trench-coated future-noir detective Tex Murphy. The Access story begins in 1982, long before the technology that enabled Tex was more than a dream, when Bruce Carver took home one of the first Commodore 64s to be sold in Salt Lake City.

Bruce was hardly your stereotypical computer whiz kid. Reared in the conservative bosom of Mormonism, he was a settled 34-year-old family man, more than ten years into a career in industrial engineering, when he bought his 64. He’d been introduced to programming some fifteen years earlier at university, then gotten a baptism by fire in his first job after, in the San Francisco offices of the Pacific Fruit Express Company.

They had a computer that no one knew how to work. One day the boss dropped a pile of manuals on my desk and, “Learn how to work this thing — I see you’ve taken Fortran in college.”

I dug through the books until I figured out how it worked and programmed a lot of it myself. By that time, I was working in machine language, something I had never done before — I was used to working with high-level languages. At that point, I fell in love with computers.

After “talking his wife into” the idea years later, he bought a Commodore 64 system from Steve Witzel, owner of a local store called Computers Plus. Bruce found the 64 captivating, rediscovering a passion for hacking that had been lying dormant all these years. Soon he was devoting all the time he could spare to figuring out how the little machine in his basement worked.

That could be a more difficult proposition than you might think. In years to come the 64 would see its humble innards plumbed and charted and exploited to a degree matched by few other platforms in computing history. Those first machines, however, preceded the foundation for most of the vast literature to follow, Commodore’s official Programmer’s Reference Guide, by almost a year. The only source early buyers had for understanding the machine was the sketchy outline provided in the manual in the form of yet another BASIC programming primer. And the 64 was an unusually inscrutable machine at that. Its BASIC was of little use for divining or exploiting the 64’s true capabilities, given that it was the exact same BASIC that Jack Tramiel had purchased from Bill Gates for the Commodore PET back in 1977. It thus lacked any support whatsoever for most of what made the 64 special, like colors and sprites and the SID sound chip. The only way to access these capabilities in BASIC was to POKE values into memory locations and to PEEK at others to see what was inside. Problem was, you had to know what these memory locations were in the first place, for which the manual was of only limited help at best. And so thousands of early adopters like Bruce Carver set out to divine them for themselves, to construct a map of the machine and its capabilities, by methodically POKEing each of the 65,535 addresses and seeing what happened. It was madness, but it was a delightful sort of madness for the right sort of mind.

Bruce’s personal obsession became the 64’s sprite system, particularly a little-understood, semi-mythical something called a “multicolor” sprite that was mentioned in passing in two tables inside the manual but otherwise went completely unremarked. As I wrote in an earlier article about the 64’s technical capabilities, and as Bruce now discovered after a “long systematic search” just to find the video chip, a multicolored sprite let you use up to three colors rather than just one to construct it, at the expense of half the object’s horizontal detail. Bruce’s discoveries led to his first real Commodore 64 project, an editor which let him design single- or multicolor sprites interactively, then save them in a format easy to incorporate into either BASIC or assembly-language. He took it to Computers Plus to show Witzel, who told him that, if he applied just a bit more polish and wrote a manual for it, he’d have a perfectly salable product. This encouragement led to the founding of Access Software just four feverish months after Bruce had first set up his Commodore 64. Witzel, who would become a lifelong friend, knew very well how software distribution and sales worked, and was thus able to help Bruce get a foot in the door of the software industry.

The box art for Spritemaster 64, Access Software’s very first product, featured Bruce Carver and his children.

Both Access’s first product and the first 64 product of its type, Spritemaster proved to be quite successful. It also led to an unexpected windfall of another sort. Bruce:

In December of 1982, I decided to attend a small Commodore dealer show in San Francisco. It was the perfect stage to introduce my new program to the public. The Commodore representative who was running the show came over and asked me if that was multicolored sprites I was displaying on the screen. I replied, yes, it was. He was so impressed with my work that he offered me a Xerox of a Commodore folder containing 64 technical information. He also warned me not to tell anyone else that I had it. So I returned home with a valuable prize that would save me many long hours of playing around with the computer.

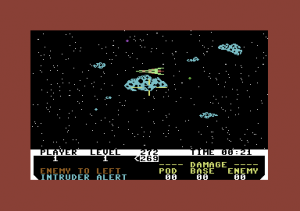

The first Access game, Neutral Zone, arose directly out of Bruce’s latest technical explorations. It placed the player in charge of a missile battery defending a space station from hordes of aliens. The big gimmick was the way that the player could pan her weapon — and with it the screen — horizontally through a full 360 degrees to target aliens who flew in from everywhere. This was accomplished by taking advantage of scrolling registers that were not even hinted at by the Commodore 64’s manual and whose existence was thus completely unknown to most programmers. Aided by that precious notebook, Bruce was developing a reputation as one of the machine’s programming gurus. While he himself would later admit that Neutral Zone “isn’t a terrific game,” it was one hell of a technical tour de force for early 1983. At another trade show, this time in Florida, the same Commodore representative approached Bruce again to praise it, apparently without recognizing the fellow for whom his own help had been so instrumental.

Neutral Zone did well enough that Bruce decided to quit his day job at Redd Engineering, managing the neat trick of convincing some of Redd’s owners to invest in Access in the process; he would soon set up Access’s first office on the top floor of Redd’s own building. At this point Chris Jones enters the stage, in the uniform not of a roguish detective but rather a mild-mannered accountant — specifically, the Redd Engineering colleague Bruce had hired to do Access’s taxes. In the midst of that, Chris became entranced with the work Bruce was doing. Never of a technical bent himself, Chris was full of creative ideas for the application of Bruce’s ever-growing mastery of Commodore 64 graphics and sound. The two now agreed to do a game together, the first “real game” from Access that had been “planned in depth ahead of time, before any programming.”

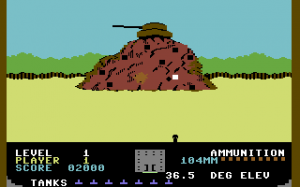

Beach-Head was inspired by the pair’s love for old World War II movies of the gung-ho John Wayne stripe. It charges you with recapturing an island that has been occupied by an enemy known only as “the Dictator.” Doing so requires the successful completion of no less than five individual action games. You must guide the invasion fleet toward the island whilst avoiding mines and torpedo attacks; fend off an enemy air attack on your fleet, followed by a surface attack; and finally storm the beaches and complete the final assault on the island’s central fortress. While hardly a cerebral exercise, it’s interesting for the amount of narrative it grafts onto its action-game template, and for being more sophisticated in some ways than you might expect. Far from being just five separate games packaged together, actions and, most importantly, casualties sustained in earlier phases actually affect later ones, leaving you with a tidy, unique little story at the end about your invasion (or invasion attempt).

Soon after Beach-Head‘s late 1983 American release, opportunity walked through the door in the form of the slick and stylish Englishman Geoff Brown, a former rock musician who owned and ran a major British software distributor called Centresoft. (In an interesting coincidence, “Center Soft” was one of the names Bruce had rejected for what became Access Software.) Brown now had the idea of starting his own software line called U.S. Gold, which would, as the name would imply, license the best games from the United States, repackage them for Europe — which would generally involve adapting them to work on cassette — and promote the living hell out of them; if there was one thing Brown was good at, it was promotion. For American publishers, U.S. Gold would be a cheap, painless way to maximize their markets, while for Geoff Brown it would turn into gold of another stripe; he would soon be driving one of only twenty Ferrari Testarossas on the roads of Britain. U.S. Gold’s client list would soon include a major swathe of the American games industry: Adventure International, Microprose, Epyx, Datasoft, SSI, Accolade, Sierra On-Line. Within a year they would own 25 percent of the British games industry, while Brown collected plenty of hate from domestic publishers for his blunt claim that American software was just better than European software as well as for an advertising budget that ran to five times the size of his nearest competitor. Yet it all started when Brown convinced Bruce Carver and his tiny company Access to let him bring Beach-Head to Europe as the very first U.S. Gold game.

Beach-Head was a perfect template for Brown’s vision for U.S. Gold: flashy, fast-paced, not very dependent on text, and thanks to its modular design very playable off cassette. “I couldn’t believe how fantastic it looked, with smooth animation and very realistic graphics,” Brown would later say. “The gameplay was like nothing I had ever seen in the UK, streets ahead of the competing UK product.” With Brown’s promotional savvy behind it, it became huge in Europe, selling in the vicinity of 150,000 units in its first year there and making of Bruce Carver a programming hero for countless European kids. Brown claims that it prompted home-grown British developers to “scrap everything they were working on” and start over to try to reach the bar set by Beach-Head. He also claims today that he shipped 1 million copies of Beach-Head through U.S. Gold, but it should be said that he is a bit prone to hyperbole and this number sounds extreme. Regardless, the game went on to become not just the most successful by far of Access’s early efforts but one of the seminal Commodore 64 titles, one that absolutely every kid with a 64 knew, owned, and played, whether legally or (as was much more the norm) illegally acquired.

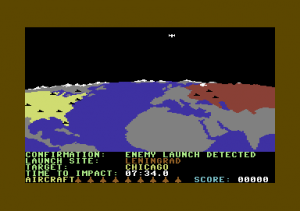

Bruce came up with the title of Access’s next game, Raid Over Moscow, whilst driving home from the Winter Consumer Electronics Show in January of 1984 with some friends. The game, another multi-stage “arcade adventure,” was designed around the name. But this time Bruce and Chris walked, by their account naively, into controversy. In place of the abstractly fictional Dictator of Beach-Head, Raid Over Moscow posits a sneak nuclear attack by the very real Soviet Union, which you must defend against using an SDI-like system. It climaxes with the eponymous assault on Moscow itself; if you succeed here you leave behind a smoking nuclear crater. In questionable taste though it was, the game attracted little concern in the United States, where its jingoism felt sadly in step with those times when Ronald Reagan’s “Evil Empire” rhetoric was reaching a peak, the real SDI program was all over the news, and the superpowers were closer to the brink of nuclear war than they had been since the Cuban Missile Crisis.

In Europe, much closer to Moscow and much more aware of the horrors of war thanks to recent history, it was a different story: Raid Over Moscow caused the proverbial shitstorm upon its release through U.S. Gold. The magazine letter pages in Britain erupted with condemnations: “nuclear war is not a subject for fantasy”; “another sick episode of this American hang-up with the people of Russia”; “provocative, insulting, and harmful”; “a nasty little number”; “vicious propaganda”; “a load of American rubbish.” Others were equally strident in declaring Raid Over Moscow harmless, “just a game,” as the controversy spread from gaming circles to television newscasts, radio shows, and of course the always overheated London tabloids. In France and West Germany the game was released as simply Raid!!!, but that didn’t help in the latter country, whose government promptly banned it — and Beach-Head for good measure — from being advertised, sold to minors at all, or even displayed on store shelves. But the most extreme reaction of all happened in Finland, where the controversy made it to the halls of Parliament and prompted an official protest from the Soviet Union to the Finnish Foreign Ministry, calling the game “military propaganda” amongst other choice epithets. Naturally, Raid Over Moscow spent the several months that followed as the top-selling Commodore 64 game in Finland.

Even as he publicly dismissed the controversy by taking the “just a game” angle, Geoff Brown rubbed his hands in glee in deference to the old maxim that no press is bad press. Bruce Carver and Chris Jones, who whatever their personal politics did seem genuinely bewildered and at least somewhat bothered by it all, later claimed that Brown deliberately sparked the flames by contacting known “hawks” and “doves” in London political circles to tell them about the game and get them squawking at each other before it even came out. Later Brown supposedly stoked them by paying people to picket the Soviet Embassy in Raid Over Moscow tee-shirts, until Bruce finally told him to please just cool it.

Meanwhile back in Nevada, the last piece of the Access puzzle had fallen into place in the form of Bruce’s younger brother Roger, who had spent the last nine years in the Navy programming mainframe-based flight simulators. Intrigued by his brother’s programming exploits, he bought a Commodore 64 of his own, and quickly made a poker game that was quite playable. Impressed, Bruce convinced Roger not to reenlist but rather to come work with him instead in June of 1984; by this time Access was turning at last into a real company, with real offices and real employees. The two brothers worked along with Chris Jones on the inevitable Beach-Head II: The Dictator Strikes Back, yet another episodic military action game but one which did stretch the formula considerably by making it possible for two players to play against each other, one in the role of the Dictator and the other in that of the hero.

Beach-Head II‘s other obvious innovation marked the onset of another of the Carvers’ longstanding technical obsessions. Inspired by the digitized speech snippet in Epyx’s Impossible Mission, they started looking for a way to incorporate speech into their own game. They caught up with Doug Mosser, whose company Electronic Speech Systems had been responsible for that snippet, at the January 1985 CES. Together the two companies were able to shoehorn quite a variety of spoken exclamations — all performed by Access’s package artist, Doug Vandergrift — into Beach-Head II, no mean feat given the limited speed and memory of the Commodore 64; just playing back one of these samples required about half of the 6502 CPU’s cycles, leaving precious little for everything else going on. While they didn’t come up with anything quite as indelible as Impossible Mission‘s “Stay a while! Stay forever!,” wounded soldiers in Beach-Head II scream for a “Medic!”; hostages whine, “Hey, don’t shoot me!”; the Dictator himself cackles and issues appropriate Evil Mastermindish threats. The Carvers would continue to relentlessly push the (often rudimentary) sound capabilities of the computers on which they worked, culminating in a patented system, which they dubbed RealSound, for getting, well, real sound and speech out of the IBM PC’s primitive bleeper of a speaker. It would be licensed to a number of other companies, until the arrival of ubiquitous sound cards made it moot.

Beach-Head II foreshadowed Access’s future in still another way. The opening sequence sees your forces parachuting into the Dictator’s stronghold from helicopters, then mounting an initial assault on the defensive perimeter. Trying to make the soldiers’ movements as realistic as possible, the three Access principals went out to a local park and filmed themselves running and scaling walls on a new video camera Roger had recently acquired. They then traced still frames of their figures to make the sprites in the game. This interest in the incorporation of live-action video footage — Roger and Chris were both to one degree or another frustrated filmmakers — would mark virtually every project Access would undertake for the next fifteen years.

For all its small-scale innovations, Beach-Head II, Access’s third episodic military action game, could be read as too much of a good thing. Sales certainly bore that out: Beach-Head had been a massive hit, Raid Over Moscow, despite all of the controversy and the attendant publicity, slightly less of one, while Beach-Head II sold yet worse. Access thus decided on a major change in direction: to make a multi-event sports simulation, a genre in which their developing motion-capture techniques might give them a big edge over the competition. From a commercial standpoint if nothing else, it made a lot of sense; Summer Games I and II from Epyx were absolutely huge in both North America and Europe (where they were released, naturally, under the U.S. Gold imprint).

The original conception for what would become Leader Board hewed very closely indeed to the Epyx model. Access imagined a game that consisted of four separate events: a baseball home-run derby, a soccer penalty kick, a “closest to the pin” golf challenge (meaning each player got three shots to get as close to a single hole as possible), and something else to be determined in the fullness of time. Roger being an excellent golfer, with a handicap that had been known to get as low as 3, they decided to make the golf challenge first. By the time they were done, it seemed obvious that they had something special, worthy of being expanded into a full-fledged 18-hole golf simulation. The other three events were forgotten, and Leader Board was born.

(The longest and most detailed accounts of Access’s early history are found in the July 1987 and August 1987 Commodore Magazine, the June/July 1985 Commodore Power Play, and Retro Gamer #120. Geoff Brown and U.S. Gold are profiled in the June 1985 ZZap!, the July 1986 Commodore User, and the October 1986 Your Computer. A sampling of reactions to Raid Over Moscow can be found in the October 1984, December 1984, February 1985, and March 1985 Computer and Video Games, and the April 1985 Sinclair User. And finally, not reading Finnish, I must admit that I sourced the Raid Over Moscow controversy in Finland straight from good old Wikipedia.)