Although the sorts of games they created are a little outside of my usual beat, I couldn’t possibly write an overview of 1984 in British gaming without including the little company with the big, unwieldy name of Ultimate Play the Game. During their glory years, which numbered no more than two, Ultimate was unabashedly worshiped amongst Spectrum owners. They took the place that the screw-ups at Imagine Software had thought was reserved for them: that of the most talented, innovative, cool, and fabulously successful developer in the country. No other Speccy developer, before or after, would ever come close to equaling Ultimate’s reputation. Amongst British gamers of a certain age or just a certain historical bent, the name “Ultimate Play the Game” is still spoken in positively reverent tones. No one, but no one, carries the mystique of Ultimate. Far from being a disadvantage, their short life only adds to their aura. They’re British gaming’s Joy Division.

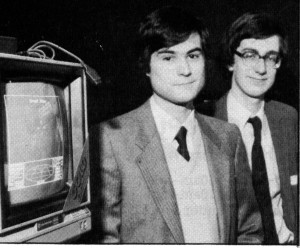

Much of Ultimate’s mystique is down to their elusiveness. When they debuted their first games in 1983, the four founders of Ashby Computer and Graphics (trading name Ultimate Play the Game) — brothers Chris and Tim Stamper along with Tim’s girlfriend (later wife) Carole Ward and John Lathbury — did the usual dance, inviting the press out to their modest office in the Midlands town of Ashby-de-la-Zouch for interviews. Little did anyone realize that those first two interviews given that summer to Home Computing Weekly and Popular Computing Weekly would also be the last. At first, so the partners claimed, they were simply too busy writing and selling games to deal with the press. But it couldn’t have taken them long to realize that their silence only intensified gamers’ fascination. It was the best kind of promotion — the kind which costs nothing and for which you have to do nothing. The veil of secrecy has never really lifted; you don’t need two hands to count the total number of sit-down interviews given by the Stampers in the last thirty years. That can make things complicated for a fellow like me, but we shall do the best we can to ferret out some facts.

Born in 1958, Chris Stamper discovered computers while studying physics and electronics at Loughborough University. He was soon making one of his own, built around an RCA 1802 microprocessor, and learning to program it; this comfort with hardware as well as software would be key to his career. By 1979 he’d finagled a job at Associated Leisure, a new British firm set up to not only import Japanese and American arcade machines into the country but to continue to support the needs of the arcade owners who purchased them once they arrived. In that spirit, Chris spent much of his time working up conversion kits which would allow an owner to, say, convert a Space Invaders machine to a Galaxian when the former started getting long in the tooth. He also found a job for his less technical little brother Tim in graphics and design, and became firm friends with John Lathbury, another coder and hardware engineer.

Their manager at Associated was a fellow named Norman Parker. Realizing the talent he had working under him, he convinced them all to leave Associated with him for a new venture: a company called Zilec, which would become one of just two British companies to manufacture and sell original arcade games. They became his secret weapons, engineering and programming games that were sold in Britain under the Zilec name or licensed to big Japanese companies like Konami and Sega.

The Stampers made a big deal of their time in the arcade industry in those first interviews as Ultimate, and with good reason. The experience they gained was invaluable. For one thing, the games they made were all built around the ubiquitous Zilog Z80, the chip also at the heart of the Sinclair Spectrum; Chris and John had every opcode and register permanently etched into their brains long before they saw their first Speccy. But just as important were the personal contacts they made. Barely out of their teens, they got to travel the world. Parker: “They saw all the best products from around the world. They learned their trade well.” They learned the delicate feint and parry of Japanese business decorum, and forged a bond with a Floridian named Joel Hochberg who had been in coin-operated entertainment since the days when that meant pinball machines; he had helped the young Nolan Bushnell launch the original Pong. Parker and Hochberg inculcated them with their own unsentimental view of electronic entertainment as first and foremost a business that should make them money. Parker:

They are completely down to earth about games. They know what a game has to do to make money. In the arcades a game has to make money immediately or it will almost literally be scrapped. They learned this important lesson from the arcade business.

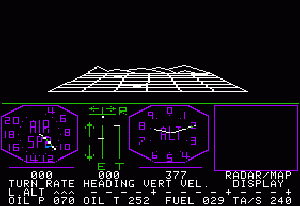

With the arcade industry beginning to go soft and British microcomputers sweeping the country, the Stamper brothers and Lathbury decided to bail on Zilec and start their own company to cater to that new market. Carole Ward came in as well as another graphic designer and “company secretary.” From the beginning, Ultimate developed games in a way very different from the typical Speccy bedroom coder. As with so much else about Ultimate, details of their development system are not entirely clear, but those early interviews do describe it as a 32-bit multi-user system on which they could write and compile their code and ship it over to an attached Spectrum for execution. (A best guess would be a 68000-based Unix workstation.) The methodology obviously borrowed heavily from that used by Zilec and their competitors for writing arcade firmware, and cost “several thousand pounds.” They chose the Spectrum, its low-end model with just 16 K of memory, as their target platform for reasons “purely economic — to finance the costs of the development system and to provide revenue quickly they needed a big-selling computer, and the 16 K Spectrum fit the bill.”

Ultimate made their public debut in mid-1983 with Jetpac, followed by a spurt of three more games in two months and no shortage of self-confidence. Tim:

There is now an awful lot of software out for the Spectrum, but ours will always sell because it’s better. We have worried a lot of our competitors. Suddenly Jetpac came out from nowhere, but in fact we have more experience than all of them. I think we have raised the user expectation of what the Spectrum can do and software houses have been forced to raise their standards in line with us.

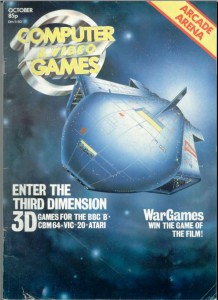

The games justified the hubris. Those early titles are fast-paced, colorful, and smartly designed, and pack a staggering amount of content into 16 K. They really did seem to transform the Speccy into a whole new machine which no one had ever suspected it had within it and which no one but Ultimate knew how to access. While gameplay remains firmly in the three-lives, ever-more-difficult-levels mold of the arcade, the concepts are not only original but, gratifyingly, have you building things rather than just blowing them up. In Pssst you’re a gardener trying to grow a flower and protect it from rampaging insects; in Cookie you’re a baker trying to make a cake, Swedish Chef-style, with animate ingredients that don’t want to be baked. Gamers responded. Ultimate was soon rewarded with the biggest overall sales in the industry and the beginnings of the incomparable reputation they still enjoy today. By year’s end their games sat at #1, #3, and #4 on Computer and Video Games‘s Spectrum sales top ten — and they had retreated into their offices, protected by thick perspex windows, an entry phone to ward off casual knockers, and “Private: Keep Out” signs on the garage at the rear that would soon hold a Lamborghini or two.

But the games that would really make Ultimate legendary would come with the next batch, for which they stepped up to the 48 K Spectrum, the one almost everyone was actually buying by now.

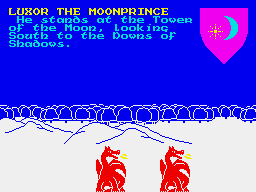

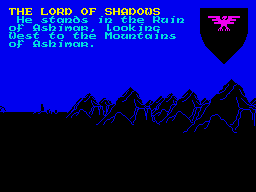

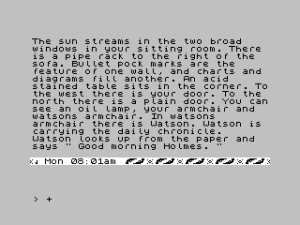

The first of these bigger games was Lunar Jetman, a sequel to their very first game Jetpac with more complex play and a vastly larger area but still with the standard arcade structure of level after level, each more difficult than the previous, unfolding until you die. Then, between that game and the next, Ultimate’s design approach underwent a quiet revolution, from bringing games that could have been arcade hits to the Spectrum to longer-form experiences that could only have been born and bred for the home. The next game, Atic Atac, is another real-time action game with Ultimate’s by-now-expected superb graphics, but it drops you into a haunted castle full of rooms to explore, connections to map, monsters to defeat or avoid, objects to pick up, little puzzles to solve, all while contending with a time limit. There’s a score, but it’s not the real point of the endeavor — that’s to collect the three keys which will let you escape the castle. If you do so, you’ve actually won and the game is over. Remind you of anything? Crash magazine’s reviewer grappled with what kind of game Atic Atac really was: “Atic Atac is no way a true adventure, but neither is it a shoot-the-baddies game.” In those days, a “true” adventure meant a text adventure (possibly with illustrations for flavor) because that’s all there was. The genre that Atic Atac pioneered would within a year be named the “action-adventure.”

Which is not to say that Ultimate was the absolute first to tread this ground. The canonical first example of the form is Warren Robinett’s game Adventure, which he coded for the Atari VCS in the United States in 1979. Robinett had seen and been fascinated by the original Crowther and Woods Adventure on a visit to Stanford University. His game for Atari was an explicit attempt to translate the elements that had intrigued him on Stanford’s big PDP-10 to a form playable on the very different hardware of the VCS — so explicit an attempt that he even appropriated the name. Robinett:

I think you could describe what I did as translating the adventure-game idea from one medium to another. You can call text-adventure games a “medium”: the output to the player is text descriptions, the player types text commands to the game. That’s all there is: no graphics, no sound, no animation. The medium I was translating to was the videogame, where you have a joystick — one button and the four directions (or eight if you want to think of it that way) — and it has graphics, has color, has animation, has sound. So it had to change to work in that medium.

Robinett’s game was primitive even by the standards of Spectrum software of just a few years later; it had to be to run in 4 K of cartridge-based ROM and 128 bytes of RAM. But it threw down a gauntlet — albeit one which few American software houses, working the fertile ground of Zork-style text adventures and Ultima- and Wizardry-style CRPGs, took up. The folks from Ultimate, who had traveled far and seen much of the international videogame business while at Zilec and thus had to have seen Robinett’s Adventure, now picked it up for Britain instead. Atic Atac and the Ultimate action-adventures which followed — Sabre Wulf, Underwurlde, Knight Lore, Alien 8, Nightshade, Gunfright, and Pentagram — touched off a veritable gaming subculture of copycats and, eventually, games which took the concept even further. The big open-world action-adventure would remain a cottage industry in British software through the end of the decade and beyond, with a string of iconic titles: Mercenary, Fairlight, Spindizzy, Head Over Heels, Exile, the Dizzy series, just for starters.

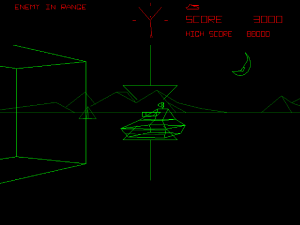

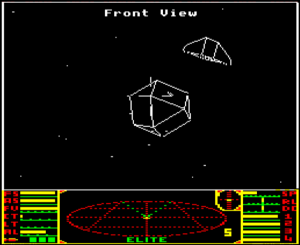

Ultimate reached their pinnacle of success at the end of 1984, when they released Underwurlde and Knight Lore simultaneously just in time for Christmas. The former was a continuation of what they had already wrought in Atic Atac and Sabre Wulf, but the latter marked the last big innovation they would gift to their eager public: the first isometric action-adventure.

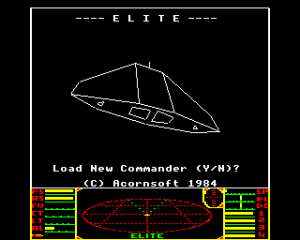

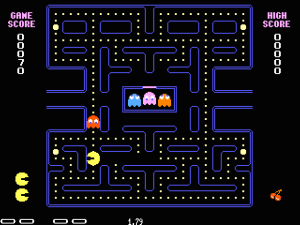

Ultimate’s worlds prior to Knight Lore, like those of virtually everyone else, were worlds of just two dimensions. (See my article on Elite for the reasons behind that and its ramifications.) They were viewed from directly above, from a strangely depthless sideways, or from even stranger, Pac-Man-like perspectives that conform to no obvious reality. Game developers had been frustrated by the limitations of 2D for years, but true 3D graphics, while David Braben and Ian Bell among others proved them not to be impossible, were very, very difficult on a simple 8-bit computer, and usually limited to wireframes if you wanted to get any performance at all out of them. Isometric perspective would turn out to offer a compromise, a way to get many of the benefits of 3D without most of the costs.

Engineers and architects had grown frustrated with the limitations of their 2D blueprints many years before videogames existed. They had realized that drawing a rectangular object like, say, a building from a sweet spot above and canted 45 degrees horizontally gave an excellent view of it in all its 3D glory without being very taxing on the drawer: it’s essentially just a matter of leaving vertical lines alone, rotating horizontal lines by -30 degrees, and rotating depth lines by +30 degrees. Best of all, a quirk in the rules of perspective means that objects deeper in the picture remain exactly the same size as those closer to the viewer — again, a huge burden lifted from the drawer. Or from the programmer and her computer. The transformations required to display an isometric view on a computer are fairly trivial compared to full 3D rendering. There are inevitable limitations — the real world isn’t generally so neatly rectangular — but, still, isometric graphics offered a magic bullet, a way to get something for, if not quite nothing, a very reduced cost.

Given that, it’s if anything surprising how slow game programmers were to catch on to their wonders. The first prominent games to use isometric graphics were a couple of arcade releases of 1982, Sega’s Zaxxon and Gottlieb’s Q*bert. Isometric graphics first came to the Spectrum in late 1983 in the form of Ant Attack, written by a young sculptor named Sandy White who applied his knowledge of real-world 3D construction to the construction of a virtual world inside his Speccy. But all of these titles were games in the traditional arcade mold. Ultimate applied the isometric perspective to a more ambitious, expansive action-adventure for the first time with Knight Lore. It was a match made in heaven; within a year virtually everyone else would make the switch as well. (One wag writing to Crash magazine labelled Knight Lore the “second most cloned piece of software after Wordstar.”) Not only did the isometric view bring a whole new depth (sorry!) of play, but it was stunning eye candy, becoming for most the ultimate (sorry again!) demonstration of Ultimate’s graphics prowess. One reviewer on a Spectrum nostalgia site: “I think that setting eyes on Knight Lore for the first time must have been like seeing King Kong on the screen back in the 1930s when the film was released. It (Knight Lore) was the single most staggering thing I’d ever seen on a Spectrum.” Another: “I was there in the computer shop on the day Knight Lore was first loaded into the demonstration Speccy. Within thirty seconds there was a crowd about seven deep, everyone clambering over each other to get a better look.” It really was that amazing. As with Ultimate itself, a gauzy patina of awe still surrounds Knight Lore today amongst British gamers. A 1994 article in Edge magazine pronounced it nothing less than “the greatest single advance in the history of computer games.” That’s an assertion that reveals a certain loss of perspective (done now, I promise!) in my opinion, but it’s nevertheless a very, very important moment whose reverberations would echo for years through British gaming and well beyond.

Knight Lore is also enshrined in Ultimate lore for another reason. In an interview given to The Games Machine magazine in December of 1987 (the first they had agreed to since those early pieces back in 1983), the Stamper brothers dropped a bombshell:

Knight Lore was finished before Sabre Wulf. But we decided then that the market wasn’t ready for it. Because if we released Knight Lore and Alien 8 — which was already half-finished — we wouldn’t have sold Sabre Wulf. So we released Sabre Wulf, which was a colossal success, and then released the other two.

This little anecdote has had huge resonance in the years since because it so confirms the legend of Ultimate as both technical and artistic geniuses (they were doing isometric action-adventures even earlier than we thought!) and iconoclastic masters of PR and marketing (who else was thinking in terms of what the market was “ready for” in the wild and wooly days of the early British software industry?). And indeed, and assuming that it’s completely true, it does show uncanny foresight of a sort which many other publishers could have used. (Just to give one example: it strikes me that Beyond and Mike Singleton would have done better to wait another few months at least before releasing Doomdark’s Revenge, to let the buzz from The Lords of Midnight run its course and fully prime the pump for the sequel.)

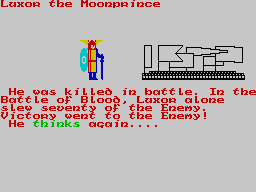

Ultimate’s star dimmed somewhat during 1985, beginning as early as the next game, Alien 8, which prompted a few grumbles amidst the usual superlative reviews that it was really just Knight Lore in Space. By the time of Nightshade and Gunfright a developing critical consensus had it that Ultimate was not only failing to advance their action-adventure formula but actually beginning to regress, offering less interesting puzzles, less control, and less to do. A handful of underwhelming Commodore 64 games done by outside contractors — this after Ultimate had sworn they would always do all of their games in-house — damaged their reputation even more. In truth, the divide in quality pre- and post-Knight Lore was probably exaggerated; the British gaming press had more than a whiff of the tabloid about it, and generally delighted in tearing down heroes even more than it enjoyed building them up. (One magazine was so cruel as to gleefully follow Mark Butler around from developer to developer as he desperately searched for a job following the Imagine Software debacle. With that example of how the press treated previous golden boys, the folks at Ultimate could probably count themselves lucky that their own fall from favor was confined to some harsh reviews.) Then, just as 1986 began, Ultimate did something else they’d said they’d never do: sold out to the big, well-funded house U.S. Gold, who had become a huge player by licensing, repackaging, and distributing American software for the British market. Some more underwhelming games followed, and then the Ultimate imprint disappeared entirely, making its final appearance on a Collected Works anthology that packaged together their first eleven Spectrum games — all of the ones which the founders had actually programmed. Lathbury and the Stampers disappeared entirely for a couple of years. Speculation about just where the hell these most legendary Speccy developers of all had gotten to ran rampant.

What had happened, it eventually emerged, was one of the strangest transformations in the history of gaming. The Stampers claim that as early as late 1983, even before the run of action-adventures which would form the cream of Ultimate’s legacy, they brought the first Nintendo Family Computers (Famicoms) into the office. These strange little toylike game consoles, completely unknown in Europe or North America, were the hottest thing going in Japan, as Ultimate knew well from their ongoing international contacts. As home consoles crashed everywhere else in the world, as the received wisdom from all the British and American pundits said that consoles were dead and home computers were the future, the Famicom was motoring past the half-million unit marker after a matter of months on the market. Tim Stamper:

The machine, for the price it was available in Japan then [about $100 US], had colossal potential — we looked at this and we looked at the Spectrum — and then the Spectrum was hot stuff, but this was incredible. So we spent possibly eight months finding everything out about this system — its custom chips, and it takes a fair bit of work — we managed to do that and then started to write on the machine.

It was at this time, around the point when Knight Lore was about to hit store shelves, that the Stamper brothers set into motion a master plan to gradually divest themselves from the Speccy. The Speccy was huge in its home country, but it was in some sense provincial; it would never penetrate far beyond Britain and a few other European markets despite hopeful arrangements with Timex and others that tried to introduce it to North America and other such tempting places. (Eastern-bloc countries cloned the hell out of it, but that of course didn’t lead to more software markets for the Western likes of Ultimate.) Yes, you might make the same argument about the Famicom, but Nintendo was a smarter company than Sinclair with far more resources at their disposal and long-term plans in the offing for worldwide domination, as the Stampers knew well from their Japanese contacts. Ultimate was doing brilliant, unprecedented things with the Speccy graphically, but the Nintendo was more obviously capable in that area right out of the box; just imagine how far they might push it. And the Famicom had one other hugely appealing quality: its programs were sold on cartridges rather than tapes or disks. This made it a much more appealing system for children, novices, and the computerphobic: playing a game was a simple matter of shoving a cartridge in and turning on the machine; no entering arcane commands, no waiting twenty minutes with fingers crossed. Best of all, cartridges made casual piracy impossible — piracy which many Speccy publishers claimed was costing them half or more of their revenue.

So, for most of the same reasons that other publishers would also cite but far, far earlier, Ultimate decided to jump on the console bandwagon. Working without manuals or Nintendo’s development kits, they figured out how the Famicom worked and developed ways to program it. Nintendo, however, ruled the Famicom ecosystem with an iron fist. The only way to publish for the machine was through them, and they weren’t in the habit of granting licenses to companies outside of Japan. Enter their old American friend Joel Hochberg, who had longstanding relationships with Nintendo. He approached Nintendo executive Minoru Arakawa and finagled a meeting for the Stampers. Nintendo was impressed enough with the demos they showed that they signed them. Hochberg and the Stampers — Lathbury quietly dropped out of the picture around this point for reasons that have never been explained — formed a new company, Rare, to develop for the Nintendo, using the money still coming in from Ultimate and, eventually, Ultimate’s sale to U.S. Gold to fund this new entity. Rare went on to become one of if not the most valued software partner of Nintendo and one of if not the most prolific and successful maker of Nintendo games outside Nintendo themselves, while the odd little Famicom went on to change everything everywhere as the Nintendo Entertainment System.

That, anyway, is the story as the Stampers have told it and the one that has gone down in gamer legend. I don’t have any evidence to refute it, although I do have a sneaking suspicion that there’s a bit of PR and self-mythologizing going on here, that it wasn’t all that meticulously plotted from the beginning. Certainly one must admit that it smacks just a bit of, say, a really convoluted Homeland plot which depends on every person reacting just so and every link on the chain connecting flawlessly. Ah, well… I suppose gamers need their legends too. Whatever the dirty details, the Stampers have proved themselves to be very adroit businessmen under anybody’s terms. And we’ll leave it at that.

Technically superlative and meticulously crafted as they are, I’m not a huge fan of Ultimate or Rare’s games in general. They’re just so commercially calculated, so plainly aimed with pinpoint precision at the center of a market demographic that I can’t feel much, for lack of a better word, soul in them. I’ll cast my lot with the dreamers and crazed would-be electronic artists instead, even if their games aren’t quite so air-tight technically. I’d perhaps feel better about the Stamper legacy if there was any mention of joy or fun in the few interviews we have with them to balance all the talk of competencies and markets and competition and games as “products.” (Tim: “We actually act, I suppose, as Nintendo’s development team. If they feel they are lacking a product on a machine, they tell us, we develop it, and so we are sure of licensing product to them.”) But I must also acknowledge that I wasn’t there when Knight Lore and the others first wowed players, and my view of them might be different if I had been. Certainly the legend of Ultimate Play the Game will live on, and perhaps that’s as it should be. Yes, gamers do need their legends.

(Magazine sources: Your Computer of June 1983; Home Computing Weekly of August 9 1983; Popular Computing Weekly of August 18 1983, November 10 1983; Personal Computer Games of Summer 1983, January 1985; Computer and Video Games of March 1986; The Games Machine of March 1988; Retro Gamer #20; Edge of September 1994; Commodore User of July 1985; Next Generation of November 1995. Warren Robinett and Atari Adventure material drawn from Racing the Beam by Nick Montfort and Ian Bogost and Jason Scott’s Get Lamp interview with Robinett. Nintendo material drawn from Game Over: How Nintendo Conquered the World by David Sheff.

Rare has consistently refused to grant permission to distribute the old Ultimate catalog and been quite aggressive with those who do so without approval. Since their lawyers are doubtless bigger than mine, no downloads this time. Sorry!)