One day in 1962 J.C.R. Licklider, head of the Defense Department’s Information Processing Techniques Office and future Infocom co-founder, ran into a young man named Robert Taylor at an intra-government conference on emerging computer technologies. Lick was seventeen years older than Taylor, but the two found they had much in common. Both had studied psychology at university, with a special research interest in the psychology of human hearing. Both had moved on to computers, to become what we might today call user-interface specialists, studying the ways that the human mind receives and processes information and how computers might be designed to work in more intuitive accord with their masters. Both were humanists, more concerned with that amorphous thing we’ve come to call the user experience than with the bits and bytes that obsessed the technicians and engineers around them. And both were also from the South — Lick from Missouri, Taylor from Texas — and spoke in a corresponding slow drawl that often caused new acquaintances to underestimate them. A friendship was formed.

Taylor was working at the time at NASA, having been hired there in the big build-up that followed President Kennedy’s Moon-before-the-decade-is-out speech to work on simulators. Rather astonishingly considering the excitement building for the drive to the Moon, Taylor found himself increasingly dissatisfied there. He wasn’t content working on the margins of even as magnificent an endeavor as this one. Fueled by his conversations with Lick about the potential of computers, he wanted to be at the heart of the action. In 1964 he got his wish. Stepping down as head of IPTO, Lick recommended that Ivan Sutherland be made his replacement, and that Taylor be made Sutherland’s immediate deputy. Barely two years later Sutherland himself stepped down, making the 34-year-old Taylor head of the most far-reaching, well-funded computer-research grant program in the country.

By this time Taylor had long ago come to share Lick’s dream of computers as more than just calculating and tabulating machines. They had the potential to become personal, interactive companions that would not replace human brainpower (as many of the strong AI proponents dreamed) but rather complement, magnify, and transmit it. Taylor put his finger on the distinction in a later interview: “I was never interested in the computer as a mathematical device, but as a communications device.” He and Lick together published a manifesto of sorts in 1968 that still stands as a landmark in the field of computer science, the appropriately named “The Computer as a Communications Device.” They meant that literally as well as figuratively: it was Taylor who initiated the program that would lead to the ARPANET, the predecessor to the modern Internet.

One of Taylor’s favorites amongst his stable of researchers became Doug Engelbart, who seemed almost uniquely capable of realizing his and Lick’s concept of a new computing paradigm in actual hardware. While developing an early full-screen text editor at the Stanford Research Institute, Engelbart found that users complained of how laborious it was to slowly move the cursor around the screen using arrow keys. To make it easier, he and his team hollowed out a small block of wood, mounting two mechanical wheels attached to potentiometers in the bottom and a button on top. They named it a “mouse,” because with the cord trailing out of the back to connect it with a terminal that’s sort of what it looked like. The strange, homemade-looking gadget was crude and awkward compared to what we use today. Nevertheless, his users found it a great improvement over the keyboard alone. The mouse was just one of many innovations of Engelbart and his team. Their work climaxed in a bravura public demonstration in December of 1968 which first exposed the public to not only the mouse but also the concepts of networked communication, multimedia, and even the core ideas behind what would become known as hypertext. Engelbart pulled out all the stops to put on a great show, and was rewarded with a standing ovation.

But to some extent by this time, and certainly by the time the ARPANET first went live the following year, the atmosphere at ARPA itself was changing. Whereas earlier Taylor was largely left to invest his resources in whatever seemed to him useful and important, the ever-escalating Vietnam War was bringing with it both tightening research budgets and demands that all research be “mission-focused” — i.e., tailored not only to a specific objective, but to a specific military objective at that. Further, Taylor found himself more and more ambivalent about both the war itself and the idea of working for the vast engine that was waging it. After being required to visit Vietnam personally several times to sort out IT logistics there, he decided he’d had enough. He resigned from ARPA at the end of 1969, accepting a position with the University of Utah, which was conducting pioneering (and blessedly civilian) research in computer graphics.

He was still there a year later when an old colleague whose research had been partially funded through ARPA, George Pake, called him. Pake now worked for Xerox Corporation, who were in the process of opening a new blue-sky research facility that he would head. One half of its staff and resources would be dedicated to Xerox’s traditional forte, filled with chemists and physicists doing materials research into photocopying technology. The other half, however, would be dedicated to computer technology in a bid to make Xerox not just the copy-machine guys but the holistic architects of “the office of the future.” Eager to exploit Taylor’s old ARPA connections, which placed him on a first-name basis with virtually every prominent computer scientist in the country, Pake offered Taylor a job as an “associate manager” — more specifically, as a sort of recruiter-in-chief and visionary-in-residence — in the new facility in Palo Alto, California, just outside Stanford University. Bored already by Mormon-dominated Salt Lake City, Taylor quickly accepted.

The very idea of a facility like Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center feels anachronistic today, what with its open-ended goals and dedication to “pure” research. When hired to run the place, Pake frankly told Xerox that they shouldn’t expect any benefits from the research that would go on there for five to ten years. In that he wasn’t entirely correct, for PARC did do one thing for Xerox immediately: it gave them bragging rights.

Xerox was a hugely profitable company circa 1970, but relatively new to the big stage. Founded back in 1906 as The Haloid Photographic Company, they had really hit the big time only in 1960, when they started shipping the first copy machine practical for the everyday office, the Xerox 914. Now they were eager to expand their empire beyond copy machines, to rival older giants like IBM and AT&T. One part of doing so must be to have a cutting-edge research facility of their own, like IBM’s Thomas J. Watson Research Center and the fabled Bell Labs. Palo Alto was chosen as the location not so much because it was in the heart of Silicon Valley as because it was a long way from the majority of Xerox’s facilities on the other coast. Like its inspirations, PARC was to be kept separate from any whiff of corporate group-think or practical business concerns.

Once installed at PARC, Taylor started going through his address book to staff the place. In a sense it was the perfect moment to be opening such a facility. The American economy was slowing, leaving fewer private companies with the spare change to fund the sort of expensive and uncertain pure research that PARC was planning. Meanwhile government funding for basic computer-science research was also drying up, due to budget squeezes and Congressional demands that every project funded by ARPA must have a specific, targeted military objective. The salad days of Taylor’s ARPA reign, in other words, were well and truly over. It all added up to a buyer’s market for PARC. Taylor had his pick of a large litter of well-credentialed thinkers and engineers who were suddenly having a much harder time finding interesting gigs. Somewhat under the radar of Pake, he started putting together a group specifically tailored to advance the dream he shared with Lick and Engelbart for a new, more humanistic approach to computing.

One of his early recruits was William English, who had served as Engelbart’s right-hand man through much of the previous decade; it was English who had actually constructed the mouse that Engelbart had conceived. Many inside SRI, English not least among them, had grown frustrated with Engelbart, who managed with an air of patrician entitlement and seemed perpetually uninterested in building upon the likes of that showstopping 1968 demonstration by packaging his innovations into practical forms that might eventually reach outside the laboratory and the exhibit hall. English’s recruitment was the prelude to a full-blown defection of Engelbart’s team; a dozen more eventually followed. One of their first projects was to redesign the mouse, replacing the perpendicularly mounted wheels with a single ball that allowed easier, more precise movement. That work would be key to much of what would follow at PARC. It would also remain the standard mouse design for some thirty years, until the optical mouse began to phase out its older mechanical ancestor at last.

Taylor was filling PARC with practical skill from SRI and elsewhere, but he still felt he lacked someone to join him in the role of conceptual thinker and philosopher. He wanted someone who could be an ally against the conventional wisdom — held still even by many he had hired — of computers as big, institutional systems rather than tools for the individual. He therefore recruited Alan Kay, a colleague and intellectual soul mate from his brief tenure at the University of Utah. Kay dreamed of a personal computer with “enough power to outrace your senses of sight and hearing, enough capacity to store thousands of pages, poems, letters, recipes, records, drawings, animations, musical scores, and anything else you would like to remember and change.” It was all pretty vague stuff, enough so that many in the computer-science community — including some of those working at PARC — regarded him as a crackpot, a fuzzy-headed dreamer slumming it in a field built on hard logic. Of course, they also said the same about Taylor. Taylor decided that Kay was just what he needed to make sure that PARC didn’t just become another exercise in incremental engineering. Sure enough, Kay arrived dreaming of something that wouldn’t materialize in anything like the form Kay imagined it until some two decades later. He called it the Dynabook. It was a small, flat rectangular box, about 9″ X 12.5″, which flipped open to reveal a screen and keyboard on which one could read, write, play, watch, and listen using media of one’s own choice. Kay was already describing a multimedia laptop computer — and he wasn’t that far away from the spirit of the iPad.

Combining the idealism of Taylor and Kay with the practical knowledge of their engineering staff and at least a strong nod toward the strategic needs of their parent corporation, PARC gradually refined its goal to be the creation of an office of the future that could hopefully also be a stepping stone on the path to a new paradigm for computing. Said office was constructed during the 1970s around four technologies developed right there at PARC: the laser printer; a new computer small enough to fit under a desk and possessed of almost unprecedented graphical capabilities; practical local-area networking in the form of Ethernet; and the graphical user interface (GUI). Together they all but encapsulated the face that computing would assume twenty years later.

Of the aforementioned technologies, the laser printer was the most immediately, obviously applicable to Xerox’s core business. It’s thus not so surprising that its creator, Gary Starkweather, was one of the few at PARC to have been employed at Xerox before the opening of the new research facility. Previous computer printers had been clanking, chattering affairs that smashed a limited set of blocky characters onto a continuous feed of yellow-tinged fan-fold paper. They were okay for program listings and data dumps but hardly acceptable for creating business correspondence. In its original implementation Starkweather’s laser printer was also ugly, an unwieldy contraption sprouting wires out of every orifice perched like a huge parasite atop a Xerox copy machine whose mechanisms it controlled. It was, however, revolutionary in that it treated documents not as a series of discrete characters but as a series of intricate pictures to be reproduced by the machinery of the copier it controlled. The advantages of the new approach were huge. Not only was the print quality vastly better, but it appeared on crisp white sheets of normal office paper. Best of all, it was now possible to use a variety of pleasing proportional fonts to replace the ugly old fixed-width characters of the line printers, to include non-English characters like umlauts and accents, to add charts, graphs, decorative touches like borders, even pictures.

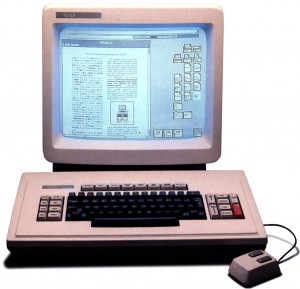

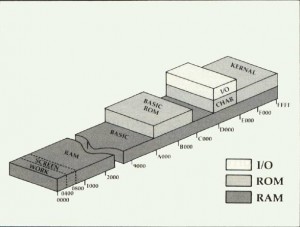

The new computer was called the Alto. It was designed to be a personal computer, semi-portable and supporting just one user, although since it was not built around a microprocessor it was not technically a microcomputer like those that would soon be arriving on the hobbyist market. The Alto’s small size made it somewhat unusual, but what most set it apart was its display.

Most computers of this period — those that were interactive and thus used a display at all, that is — had no real concept of managing a display. They rather simply dumped their plain-text output, fire-and-forget fashion, to a teletype printer or terminal. (For example, it was on the former devices that the earliest text adventures were played, with the response to each command unspooling onto fan-folded paper.) Even more advanced systems, like the full-screen text editors with which Engelbart’s team had worked, tracked the contents of the screen only as a set of cells, each of which could contain a single fixed-width ASCII character; no greater granularity was possible, nor shapes that were not contained in the terminal’s single character set. Early experiments with computer graphics, such as the legendary Spacewar! game developed at MIT in the early 1960s, used a technique known as vector graphics, in which the computer manually controlled the electron gun which fired to form the images on the screen. A picture would be stored not as a grid of pixels but as a series of instructions — the sequence of strokes used to draw it on the display. (This is essentially the same technique as that developed by Ken Williams to store the graphics for On-Line’s Hi-Res Adventure line years later.) Because the early vector displays had no concept of display memory at all, a picture would have to be traced out many times per second, else the phosphors on the display would fade back to black. Such systems were not only difficult to program but much too coarse to allow the intricacies of text.

The Alto formed its display in a different way — the way the device you’re reading this on almost certainly does it. It stored the contents of its screen in memory as a grid of individual pixels, known as a bitmap. One bit represented the on/off status of one pixel; a total of 489,648 of them had to be used to represent the Alto’s 606 X 808 pixel black-and-white screen. (The Alto’s monitor had an unusual portrait orientation that duplicated the dimensions of a standard 8 1/2″ X 11″ sheet of office paper, in keeping with its intended place as the centerpiece of the office of the future.) This area of memory, often called a frame buffer during these times when it was a fairly esoteric design choice, was then simply duplicated onto the monitor screen by the Alto’s video hardware. Just as the laser printer saw textual documents as pictures to be reproduced dot by dot, the Alto saw even its textual displays in the same way. This approach was far more taxing on memory and computing power than traditional approaches, but it had huge advantages. Now the user needed no longer be restricted to a single font; she could have a choice of type styles, or even design her own. And each letter needed no longer fit into a single fixed-size cell on the screen, meaning that more elegant and readable proportional fonts were now possible.

Amongst many other applications, the what-you-see-is-what-you-get word processor was born on the Alto as a direct result of its bitmapped display. A word processor called Gypsy became the machine’s first and most important killer app. Using Gypsy, the user could mix fonts and styles and even images in a document, viewing it all onscreen exactly as it would later look on paper, thanks to the laser printer. The combination was so powerful, went so far beyond what people had heretofore been able to expect of computers or typewriters, that a new term, “desktop publishing,” was eventually coined to describe it. Suddenly an individual with an Alto and a laser printer could produce work that could rival — in appearance, anyway — that of a major publishing house. (As PARC’s own David Liddle wryly said, “Before that, you had to have an article accepted for publication to see your words rendered so beautifully. Now it could be complete rubbish, and still look beautiful.”) Soon even the professionals would be abandoning their old paste boards and mechanical typesetters. Ginn & Co., a textbook-publishing subsidiary of Xerox, became the first publishers in the world to go digital, thanks to a network of laser printers and Altos running Gypsy.

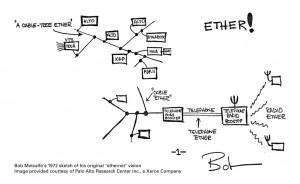

Speaking of which: the Ethernet network was largely the creation of PARC researcher Robert Metcalfe. Various networking schemes had been proposed and sometimes implemented in the years before Ethernet, but they all carried two big disadvantages: they were proprietary, limited to the products of a single company or even to a single type of machine; and they were fragile, prone to immediate failure if the smallest of their far-flung elements should break down. Ethernet overcame both problems. It was a well-documented standard that was also almost absurdly simple to implement, containing the bare minimum needed to accomplish the task effectively and absolutely nothing else. This quality also made it extremely reliable, as did its decentralized design that made it dependent on no single computer on the network to continue to function. Unlike most earlier networking systems, which relied upon a charged cable like that used by the telephone system, Ethernet messages could pass through any passive conductive medium, including uncharged copper wire of the sort sold by the ream in any hardware store. The new protocol was simpler, cheaper, safer, and more reliable than anything that had come before.

Like so much else at PARC, Ethernet represented both a practical step toward the office of the future and a component of Taylor’s idealistic crusade for computers as communications devices. In immediate, practical terms, it let dozens of Altos at PARC or Ginn & Co. share just a few of Starkweather’s pricy laser printers. In the long run, it provided the standard by which millions of disparate devices could talk to one another — the “computer as a communications device” in its purest terms. Ethernet remains today one of the bedrock technologies of the hyper-connected world in which we live, a basic design so effective at what it does that it still hasn’t been improved upon.

The GUI was the slowest and most gradual of the innovations to come to PARC. When the Alto was designed, Engelbart and English’s mouse was included. However, it was pictured as being used only for the specialized function for which they had originally designed it: positioning the cursor within a text document, a natural convenience for the centerpiece of the office of the future. But then Alan Kay and his small team, known as the “lunatic fringe” even amongst the others at PARC, got their hands on some Altos and started to play. Unlike the hardcore programmers and engineers elsewhere at PARC, Kay’s team had not been selected on the basis of credentials or hacking talent. Kay rather looked for people “with special stars in their eyes,” dreamers and grand conceptual thinkers like him. Any technical skills they might lack, he reasoned, they could learn, or rely on other PARC hackers to provide; one of his brightest stars was Diana Merry, a former secretary for a PARC manager who just got what Kay was on about and took to coming to his meetings. Provided the Alto, the closest they could come to Kay’s cherished Dynabook, they went to work to make the technology sing. They developed a programming language called Smalltalk that was not only the first rigorously object-oriented language in history, the forerunner to C++, Java, and many others, but also simple enough for a grade-school kid to use. With Smalltalk they wrote a twelve-voice music synthesizer and composer (“Twang”), sketching and drawing programs galore, and of course the inevitable games (a networked, multiplayer version of the old standard Star Trek was a particular hit). Throughout, they re-purposed the mouse in unexpected new ways.

Kay and his team realized that many of the functions they were developing were complementary; it was likely that users would want to do them simultaneously. One might, for example, want to write an instructional document in a text editor at the same time as one edited a diagram meant for it in a drawing program. They developed tools to let users do this, but ran into a problem: the Alto’s screen, just the size of a single sheet of paper, simply couldn’t contain it all. Returning yet again to the idea of the office of the future, Kay asked what people in real offices did when they ran out of space on their desk. The answer, of course, was that they simply piled the document they were using at that instant on top of the one they weren’t, then proceeded to flip between the documents as needed. From there it all just seemed to come gushing out of Kay and his team.

In February of 1975 Kay called together much of PARC, saying he had “a few things to show them.” What they saw was a rough draft of the graphical user interface that we all know today: discrete, overlapping windows; mouse-driven navigation; pop-up menus. In a very real way it was the fruition of everything they had been working on for almost five years, and everything Taylor and Kay had been dreaming of for many more. At last, at least in this privileged research institution, the technology was catching up to their dreams. Now, not quite two years after the Alto itself had been finished, they knew what it needed to be. Kay and the others at PARC would spend several more years refining the vision, but the blueprint for the future was in place already in 1975.

Xerox ultimately received little of the benefit they might have from all this visionary technology. A rather hidebound, intensely bureaucratic management structure never really understood the work that was going on at PARC, whose personnel they thought of as vaguely dangerous, undisciplined and semi-disreputable. Unsurprisingly, they capitalized most effectively on the PARC invention closest to the copier technology they already understood: the laser printer. Even here they lost years to confusion and bureaucratic infighting, allowing IBM to beat them to the market with the world’s first commercial laser printer. However, Starkweather’s work finally resulted in the smaller, more refined Xerox 9700 of 1977, which remained for many years a major moneymaker. Indeed, all of the expense of PARC was likely financially justified by the 9700 alone.

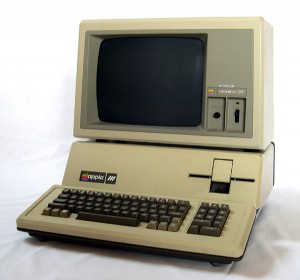

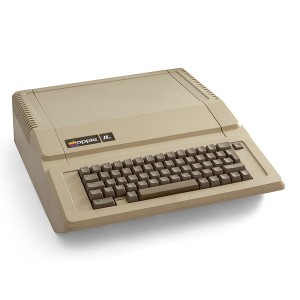

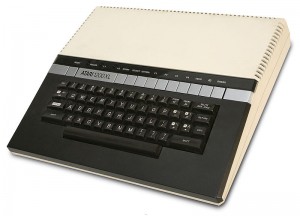

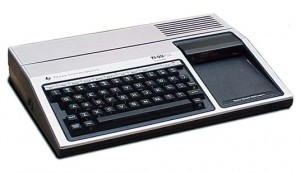

Still, the bulk of PARC’s innovations went comparatively unexploited. During the late 1970s Xerox did sell Alto workstations to a small number of customers, among them Sweden’s national telephone service, Boeing, and Jimmy Carter’s White House. Yet the commercialization of the Alto, despite pleading from many inside PARC who were growing tired of seeing their innovations used only in their laboratories, was never regarded by Xerox’s management as more than a cautious experiment. With a bit of corporate urgency, Altos could easily have been offered for sale well before the trinity of 1977 made its debut. While a more expensive machine designed for a very different market, a computer equipped with a full GUI for sale before the likes of the Apple II, TRS-80, and PET would likely have dramatically altered the evolution of the PC and made Xerox a major player in the PC revolution. Very possibly they might have ended up playing a role similar to that of IBM in our own timeline — only years earlier, and with better, more visionary technology.

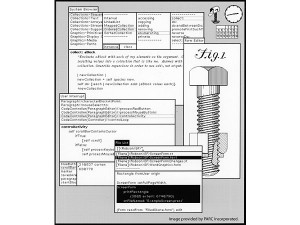

Xerox’s most concerted attempt to exploit the innovations of PARC as a whole came only in 1981, in the form of the Xerox Star “office information system.” The product of an extended six years of troubled development shepherded to release against the odds at last by ex-PARCer David Liddle, the Star did it all, and often better than it had been done inside PARC itself. The innovations of Kay and his researchers — icons, windows, scroll bars, sliders, pop-up menus — were refined into the full desktop metaphor that remains with us today, the perfect paradigm for the office of the future. Also included in each Star was a built-in Ethernet port to link it with its peers as well as the office laser printer. The new machine represented the commercial fruition of everything PARC had been working toward for the last decade.

Alas, the Star was a commercial failure. Its price of almost $17,000 per workstation meant that assembling a full office of the future could easily send the price tag north of $100,000. It also had the misfortune to arrive just a few months before the IBM PC, a vastly simpler, utilitarian design that lacked the Star’s elegance but was much cheaper and open to third-party hardware and software. Marketed as a very unconventional piece of conventional office equipment rather than a full-fledged PC, the Star was by contrast locked into the hardware and software Xerox was willing to provide. In the end Xerox managed to sell only about 30,000 of them — a sad, anticlimactic ending to the glory days of innovation at PARC. (The same year that the Star was released Robert Taylor left PARC, taking the last remnants of his original team of innovators with him. By this time Alan Kay was already long gone, driven away by management’s increased demands for practical, shorter-term projects rather than leaps of faith.)

Like the Alto, the Star’s influence would be far out of proportion to the number produced. It is after all to this machine that we owe the ubiquitous desktop metaphor. If anything, the innovations of the Star tend to go somewhat under-credited today in the understandable rush to lionize the achievements inside PARC proper. Perhaps this is somewhat down to Xerox’s dour advertising rhetoric that presented the Star as “just” an “office administration assistant”; those words don’t exactly smack of a machine to change the world.

Oddly, the Star’s fate was just the first of a whole string of similar disappointments from many companies. The GUI and the desktop metaphor were concepts that seemed obviously, commonsensically better than the way computers currently worked to just about everyone who saw them, but it would take another full decade for them to remake the face of the general-purpose PC. Those years are littered with failures and disappointments. Everyone knew what the future must be like, but no one could quite manage to get there. We’ll look at one of the earliest and most famous of these bumps on the road next time.

(Despite some disconcerting errors of fact about the computing world outside the laboratory, Michael A. Hiltzik’s Dealers of Lightning is the essential history of Xerox PARC, and immensely readable to boot. If you’re interested in delving into what went on there in far more detail than I can provide in a single blog post, it’s your obvious next stop.)