…he explains to her that Sinclair, the British inventor, had a way of getting things right, but also exactly wrong. Foreseeing the market for affordable personal computers, Sinclair decided that what people would want to do with them was to learn programming. The ZX81, marketed in the United States as the Timex 1000, cost less than the equivalent of a hundred dollars, but required the user to key in programs, tapping away on that little motel keyboard-sticker. This had resulted both in the short market-life of the product and, in Voytek’s opinion, twenty years on, in the relative preponderance of skilled programmers in the United Kingdom. They had had their heads turned by these little boxes, he believes, and by the need to program them. “Like hackers in Bulgaria,” he adds, obscurely.

“But if Timex sold it in the United States,” she asks him, “why didn’t we get the programmers?”

“You have programmers, but America is different. America wanted Nintendo. Nintendo gives you no programmers…”

— William Gibson, Pattern Recognition

A couple of years ago I ventured out of the man cave to give a talk about the Amiga at a small game-development conference in Oslo. I blazed through as much of the platform’s history as I could in 45 minutes or so, emphasizing for my audience of mostly young students from a nearby university the Amiga’s status as the preeminent gaming platform in Europe for a fair number of years. They didn’t take much convincing; even this crowd, young as they were, had their share of childhood memories involving Amiga 500s and 1200s. Mostly they seemed surprised that the Amiga hadn’t ever been all that terribly popular in the United States. During the question-and-answer session, someone asked a question that stopped me short: if American kids hadn’t been playing games on their Amigas, just what the hell had they been playing on?

The answer itself wasn’t hard to arrive at: the sorts of kids who migrated from 8-bit Sinclairs, Acorns, Amstrads, and Commodores to 16-bit Amigas and Atari STs in Britain made a much more lateral move in the United States, migrating to the 8-bit Nintendo Entertainment System.

More complex and interesting are the ramifications of these trends. Because the Atari VCS console was never a major presence in Britain and the rest of Europe during its heyday, and because Nintendo arrived only very belatedly, for many years videogames played in the home there meant games played on home computers. One could say much about how having a device useful for creation as well as consumption as the favored platform of most people affected the market across Europe. The magazines were filled with stories of bedroom gamers who had become bedroom coders and finally Software Stars. Such stories make a marked contrast to an American console-gaming magazine like Nintendo Power, all about consumption without the accompanying ethos of creation.

But most importantly for our purposes today, the relative neglect of Britain in particular by the big computing powers in the United States and Japan — for many years, Commodore was the only company of either nation to make a serious effort to sell their machines into British homes — gave space for a flourishing domestic trade in homegrown machines. When Britain became the nation with the most computers per capita on the planet at mid-decade, most of the computers in question bore the logo of either Acorn or Sinclair, the two great rivals at the heart of the young British microcomputer industry.

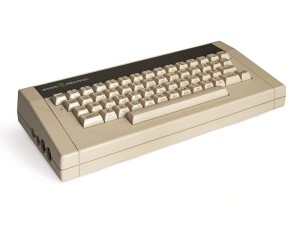

Acorn, co-founded by Clive Sinclair’s former right-hand man Chris Curry and an Austrian academic named Hermann Hauser, was an archetypal example of an engineering-driven company. Their machines were a little more baroque, a little better built, and consequently a little more expensive than they needed to be, while their public persona was reserved and just a little condescending, much like that of the BBC that had given its official imprimatur to Acorn’s most popular machine, the BBC Micro. Despite “Uncle Clive’s” public reputation as the British Inspector Gadget, Sinclair was just the opposite; cheap and cheerful, they had the common touch. Acorns sold to the educators, to the serious hobbyists, and to the posh, while Sinclairs dominated with the masses.

Yet Acorn and Sinclair were similar in one important respect: they were both in their own ways very poorly managed companies. When the British home-computer market hit an iceberg in 1985, both were caught in untenable positions, drowning in excess inventory. Acorn — quintessentially British, based in the storied heart of Britain’s “Silicon Fen” of Cambridge — was faced with a choice between dissolution and selling themselves to the Italian typewriter manufacturer Olivetti; after some hand-wringing, they chose the latter course. Sinclair also sold out: to the new kid on the block of British computing, Amstrad, owned by a gruff Cockney with a penchant for controversy named Alan Sugar who was well on his way to becoming the British Donald Trump.

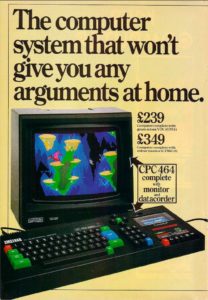

Ever mindful of the practical concerns of their largely working-class customers, Amstrad made much of the CPC’s bundled monitor in their advertising, noting that Junior could play on the CPC without tying up the family television.

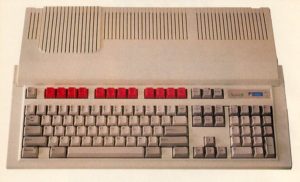

Amstrad had already been well-established as a maker of inexpensive stereo equipment and other consumer electronics when their first computers, the CPC (“Colour Personal Computer”) line, debuted in June of 1984. The CPC range was created and sold as a somewhat more capable Sinclair Spectrum. It consisted of well-built and smartly priced if technically unimaginative computers that were fine choices for gaming, boasting as they did reasonably good if hardly revolutionary graphics and sound. Like most Amstrad products, they strained to be as easy to use as possible, shipping as complete units — tape or disk drive and monitor included — at a time when virtually all of their rivals had to be assembled piece by piece via separate purchases.

The CPC line did very well from the outset, even as Acorn and Sinclair were soon watching their own sales implode. Pundits attributed the line’s success to what they called “the Amstrad Effect”: Alan Sugar’s instinct for delivering practical products at a good price at the precise instant when the technology behind them was ready for the mass market — i.e., was about to become desirable to his oft-stated target demographic of “the truck driver and his wife.” Sugar preferred to let others advance the technical state of the art, then swoop in to reap the rewards of their innovations when the time was right. The CPC line was a great example of him doing just that.

But the most dramatic and surprising iteration of the Amstrad Effect didn’t just feed the existing market for colorful game machines; it found an entirely new market segment, one that Amstrad’s competitors had completely missed until now. The story of the creation of the Amstrad PCW line is a classic tale of Alan Sugar, a man who knew almost nothing about computers but knew all he needed to about the people who bought them.

One day just a few months after the release of the first CPC machines, Sugar found himself in an airplane over Asia with Bob Watkins, one of his most trusted executives. A restless Sugar asked Watkins for a piece of paper, and proceeded to draw on it a contraption that included a computer, a monitor, a disk drive, and a printer, all in one unit. Looking at the market during the run-up to the CPC launch, Sugar had recognized that the only true mainstream uses for the current generation of computers in the home were as game machines and word processors. With the CPC, he had the former application covered. But what about the latter? All of the inexpensive machines currently on the market, like the Sinclair Spectrum, were oriented toward playing games rather than word processing, trading the possibility of displaying crisp 80-column text for colorful graphics in lower resolutions. Meanwhile all of the more expensive ones, like the BBC Micro, were created by and for hardcore techies rather than Sugar’s truck drivers. If they could apply their patented technology-for-the-masses approach to a word processor for the home and small business — making a cheap, well-built, all-in-one design emphasizing ease of use for the common person — Amstrad might just have another hit on their hands, this time in a market of their own utterly without competition. Internally, the project was named after Sugar’s secretary Joyce, since it would hopefully make her job and those of many like her much easier. It would eventually come to market as the “PCW,” or “Personal Computer Word Processor.”

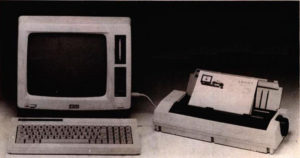

The first Amstrad PCW machine, complete with bundled printer. Note how the disk drive and the computer itself are built into the same case as the monitor, a very unusual design for the period.

Even more so than the CPC, the PCW was a thoroughly underwhelming package for technophiles. It was build around the tried-and-true Z80 8-bit CPU and ran CP/M, an operating system already considered obsolete by big business, MS-DOS having become the standard in the wake of the IBM PC. The bundled word-processing software, contracted out to a company called Locomotive Software, wasn’t likely to impress power users of WordStar or WordPerfect overmuch — but it was, in keeping with the Amstrad philosophy, unusually friendly and easy to use. Sugar knew his target customers, knew that they “didn’t give a shit whether there was an elastic band or an 8086 or a 286 driving the thing. They wouldn’t know what you were talking about.”

As usual, most of Amstrad’s hardware-engineering efforts went into packaging and cost-cutting. It was decided that the printer would have to be housed separately from the system unit for technical reasons, but otherwise the finished machine conformed remarkably well to Sugar’s original vision. Best of all, it had a price of just £399. By way of comparison, Acorn’s most recent BBC Micro Model B+ had half as much memory and no disk drive, monitor, or printer included — and was priced at £499.

Nervous as ever about intimidating potential customers, Amstrad was at pains to market the PCW first and foremost as a turnkey word-processing solution for homes and small businesses, as a general-purpose computer only secondarily if at all. “It’s more than a word processor for less than most typewriters,” ran their tagline. At the launch event in the heart of the City in August of 1985, three female secretaries paraded across the stage: a snooty one who demanded one of the competition’s expensive computer systems; a tarty one who said a typewriter was more than good enough; and a smart, reasonable one who naturally preferred the PCW. Man-of-the-people Sugar crowed extravagantly that Amstrad had “brought word-processing within the reach of every small business, one-man band, home-worker, and two-finger typist in the country.” Harping on one of his favorite themes, he noted that once again Amstrad had “produced what the customer wants and not a boffin’s ego trip.”

Sugar’s aggressive manner may have grated with many buttoned-down trade journalists, but few could deny that he might just open up a whole new market for computers with the PCW. Electrical Retailer and Trader was typical, calling the PCW “a grown-up computer that does something people want, packaged and sold in a way they can understand, at a price they’ll accept.” But even that note of optimism proved far too mild for the reality of the machine’s success. The PCW exploded out of the gate, selling 350,000 units in the first eight months. It probably could have sold a lot more than that, but Amstrad, caught off-guard by the sales numbers despite their founder’s own bullishness on the product, couldn’t make and ship them fast enough.

Surprisingly for such a utilitarian package, the PCW garnered considerable loyalty and even love among the millions in Britain and all across Europe who eventually bought one. Their enthusiasm was enough to sustain a big, glossy newsstand magazine dedicated to the PCW alone — an odd development indeed for this machine that seemed on the face of it to be anything but a hacker’s darling. A thriving software ecosystem that reached well beyond word processing sprung up around the machine. Despite the PCW’s monochrome display and virtually nonexistent animation and sound capabilities, even games were far from unheard of on the platform. For obvious reasons, text adventures in particular became big favorites of PCW owners; with its comfortable full-travel keyboard, its fast disk drive, its relatively cavernous 256 K of memory, and its 80-column text display, a PCW was actually a far better fit for the genre than the likes of a Sinclair Spectrum. The PCW market for text adventures was strong enough to quite possibly allow companies like Magnetic Scrolls and Level 9 to hang on a year or two longer than they might otherwise have managed.

So, Amstrad was already soaring on the strength of the CPC and especially the PCW when they shocked the nation and cemented their position as the dominant force in mainstream British computing with the acquisition of Sinclair in April of 1986. Eminently practical man of business that he was, Sugar bought Sinclair partly to eliminate a rival, but also because he realized that, home-computer slump or no, the market for a machine as popular as the Sinclair Spectrum wasn’t likely to just disappear overnight. He could pick up right where Uncle Clive had left off, selling the existing machine just as it was to new buyers who wanted access to the staggering number of cheap games available for the platform. Sugar thought he could make a hell of a lot of money this way while needing to expend very little effort.

Once again, time proved him more correct than even he had ever imagined. Driven by that huge base of games, demand for new Spectrums persisted into the 1990s. Amstrad repackaged the technology from time to time and, perhaps most importantly, dramatically improved on Sinclair’s infamously shoddy quality control. But they never seriously re-imagined the Spectrum. It was now what Sugar liked to call “a commodity product.” He compared it to suntan lotion of all things: the department stores “put it in their window in July and August and they take it away in the winter.” The Spectrum’s version of July and August was of course November and December; every Christmas sparked a new rush of sales to the parents of a new group of youngsters just coming of age and discovering the magic of videogames.

A battered and uncertain Acorn, now a subsidiary of Olivetti, faced a formidable rival indeed in Alan Sugar’s organization. In a sense, the fundamental dichotomies hadn’t changed that much since Amstrad took Sinclair’s place as the yin to Acorn’s yang. Acorn remained as technology-driven as ever, while Amstrad was all about giving the masses what they craved in the form of cheap computers that were technically just good enough. Amstrad, however, was a much more dangerous form of people’s computer company than had been their predecessor in the role. After releasing some notoriously shoddy stereo equipment under the Amstrad banner in the 1970s and paying the price in returns and reputation, Alan Sugar had learned a lesson that continued to elude Clive Sinclair: that selling well-built, reliable products, even at a price of a few more quid on the final price tag and/or a few less in the profit margin, pays off more than corner-cutting in the long run. Unlike Uncle Clive, who had bumbled and stumbled his way to huge success and just as quickly back to failure, Sugar was a seasoned businessman and a master marketer. The diffident boffins of Acorn looked destined to have a hard time against a seasoned brawler like Sugar, raised on the mean streets of the cutthroat Tottenham Court Road electronics trade. It hardly seemed a fair fight at all.

But then, in the immediate wake of their acquisition by Olivetti nothing at all boded all that well for Acorn. New hardware releases were limited to enhanced versions of the 1981-vintage, 8-bit BBC Micro line that were little more ambitious than Amstrad’s re-packagings of the Spectrum. It was an open secret that Acorn was putting much effort into designing a new CPU in-house to serve as the heart of their eventual next-generation machine, an unprecedented step in an industry where CPU-makers and computer-makers had always been separate entities. For many, it seemed yet one more example of Acorn’s boffinish tendencies getting the best of them, causing them to laboriously reinvent the wheel rather than do what the rest of the microcomputer world was doing: grabbing a 68000 from Motorola or an 80286 from Intel and just getting on with the 16-bit machine their customers were clamoring for. While Acorn dithered with their new chip, they continued to fall further and further behind Amstrad, who in the wake of the Sinclair acquisition had now gone from a British home-computer market share of 0 to 60 percent in less than two years. Acorn was beginning to look downright irrelevant to many Britons in the market for the sorts of affordable, practical computer systems Amstrad was happily providing them with by the bucketful.

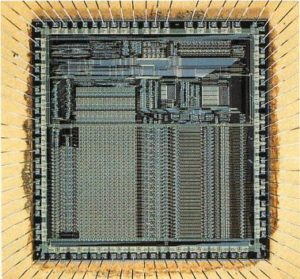

Measured in terms of public prominence, Acorn’s best days were indeed already behind them; they would never recapture those high-profile halcyon days of the early 1980s, when the BBC Micro had first been anointed as the British establishment’s officially designated choice for those looking to get in on the ground floor of the computer revolution. Yet the new CPU they were now in the midst of creating, far from being a pointless boondoggle, would ultimately have a far greater impact than anything they’d done before — and not just in Britain but over the entire world. For the CPU architecture Acorn was creating in those uncertain mid-1980s was the one that has gone on to become the most popular ever: the ubiquitous ARM. Since retrofitted into “Advanced RISC Machine,” “ARM” originally stood for “Acorn RISC Machine.” Needless to say, no one at Acorn had any idea of the monster they were creating. How could they?

“RISC” stands for “Reduced Instruction Set Computer.” The idea didn’t originate with Acorn, but had already been kicking around American university and corporate engineering departments for some time. (As Hermann Hauser later wryly noted, “Normally British people invent something, and the exploitation is in America. But this is a counterexample.”) Still, the philosophy behind ARM was adhered to by only a strident minority before Acorn first picked it up in 1983.

The overwhelming trend in commercial microprocessor design up to that point had been for chips to offer ever larger and more complex instruction sets. By making “opcodes” — single instructions issued directly to the CPU — capable of doing more in a single step, machine-level code could be made more comprehensible for programmers and the programs themselves more compact. RISC advocates came to call this traditional approach to CPU architecture “CISC,” or “Complex Instruction Set Computing.” They believed that CISC was becoming increasingly counterproductive with each new generation of microprocessors. Seeing how the price and size of memory chips continued to drop significantly almost every year, they judged — in the long term, correctly — that memory usage would become much less important than raw speed in future computers. They therefore also judged that it would be more than acceptable in the future to trade smaller programs for faster ones. And they judged that they could accomplish exactly that trade-off by traveling directly against the prevailing winds in CPU design — by making a CPU that offered a radically reduced instruction set of extremely simple opcodes that were each ruthlessly optimized to execute very, very quickly.

A program written for a RISC processor might need to execute far more opcodes than the same program written for a CISC processor, but those opcodes would execute so quickly that the end result would still be a dramatic increase in throughput. Yes, it would use more memory, and, yes, it would be harder to read as machine code — but already fewer and fewer people were programming computers at such a low level anyway. The trend, which they judged likely only to accelerate, was toward high-level languages that abstracted away the details of processor design. In this prediction again, time would prove the RISC advocates correct. Programs may not even need to be as much larger as one might think; RISC advocates argued, with some evidence to back up their claims, that few programs really took full advantage of the more esoteric opcodes of the CISC chips, that the CISC chips were in effect being programed as if they were RISC chips much of the time anyway. In short, then, a definite but not insubstantial minority of academic and corporate researchers were beginning to believe that the time was ripe to replace CISC with RISC.

And now Acorn was about to act on their belief. In typical boffinish fashion, their ARM project was begun as essentially a personal passion project by Roger Wilson [1]Roger Wilson now lives as Sophie Wilson. As per my usual editorial policy on these matters, I refer to her as “he” and by her original name only to avoid historical anachronisms and to stay true to the context of the times. and Steve Furber, two key engineers behind the original BBC Micro. Hermann Hauser admits that for quite some time he gave them “no people” and “no money” to help with the work, making ARM “the only microprocessor ever to be designed by just two people.” When talks began with Olivetti in early 1985, ARM remained such a back-burner long-shot that Acorn never even bothered to tell their potential saviors about it. But as time went on the ARM chip came more and more to the fore as potentially the best thing Acorn had ever done. Having, almost perversely in the view of many, refused to produce a 16-bit replacement for the BBC Micro line for so long, Acorn now proposed to leapfrog that generation entirely; the ARM, you see, was a 32-bit chip. Early tests of the first prototype in April of 1985 showed that at 8 MHz it yielded an average throughput of about 3.5 MIPS, compared to 2.5 MIPS at 10 MHz for the 68020, the first 32-bit entry in Motorola’s popular 68000 line of CISC processors. And the ARM was much, much cheaper and simpler to produce than the 68020. It appeared that Wilson and Furber’s shoestring project had yielded a world-class microprocessor.

ARM made its public bow via a series of little-noticed blurbs that appeared in the British trade press around October of 1985, even as the stockbrokers in the City and BBC Micro owners in their homes were still trying to digest the news of Acorn’s acquisition by Olivetti. Acorn was testing a new “super-fast chip,” announced the magazine Acorn User, which had “worked the first time”: “It is designed to do a limited set of tasks very quickly, and is the result of the latest thinking in chip design.” From such small seeds are great empires sown.

The machine that Acorn designed as a home for the new chip was called the Acorn Archimedes — or at times, because Acorn had been able to retain the official imprimatur of the BBC, the BBC Archimedes. It was on the whole a magnificent piece of kit, in a different league entirely from the competition in terms of pure performance. It was, for instance, several times faster than a 68000-based Amiga, Macintosh, or Atari ST in many benchmarks despite running at a clock speed of just 8 MHz, roughly the same as all of the aforementioned competitors. Its graphic capabilities were almost as impressive, offering 256 colors onscreen at once from a palette of 4096 at resolutions as high as 640 X 512. So, Acorn had the hardware side of the house well in hand. The problem was the software.

Graphical user interfaces being all the rage in the wake of the Apple Macintosh’s 1984 debut, Acorn judged that the Archimedes as well had to be so equipped. Deciding to go to the source of the world’s very first GUI, they opened a new office for operating-system development a long, long way from their Cambridge home: right next door to Xerox’s famed Palo Alto Research Center, in the heart of California’s Silicon Valley. But the operating-system team’s progress was slow. Communication and coordination were difficult over such a distance, and the team seemed to be infected with the same preference for abstract research over practical product development that had always marked Xerox’s own facility in Palo Alto. The new operating system, to be called ARX, lagged far behind hardware development. “It became a black hole into which we poured effort,” remembers Wilson.

At last, with the completed Archimedes hardware waiting only on some software to make it run, Acorn decided to replace ARX with something they called Arthur, a BASIC-based operating environment very similar to the old BBC BASIC with a rudimentary GUI stuck on top. “All operating-system geniuses were firmly working on ARX,” says Wilson, “so we couldn’t actually spare any of the experts to work on Arthur.” The end result did indeed look like something put together by Acorn’s B team. Parts of Arthur were actually written in interpreted BASIC, which Acorn was able to get away with thanks to the blazing speed of the Archimedes hardware. Still, running Arthur on hardware designed for a cutting-edge Unix-like operating system with preemptive multitasking and the whole lot was rather like dropping a two-speed gearbox into a Lamborghini; it got the job done, after a fashion, but felt rather against the spirit of the thing.

When the Archimedes debuted in August of 1987, its price tag of £975 and up along with all of its infelicities on the software side gave little hope to those not blinded with loyalty to Acorn that this extraordinary machine would be able to compete with Amstrad’s good-enough models. The Archimedes was yet another Acorn machine for the boffins and the posh. Most of all, though, it would be bought by educators who were looking to replace aging BBC Micros and might still be attracted by the BBC branding and the partial compatibility of the new machine with the old, thanks to software emulators and the much-loved BBC BASIC still found as the heart of Arthur.

Even as Amstrad continued to dominate the mass market, a small but loyal ecosystem sprang up around the Archimedes, enough to support a software scene strong on educational software and technical tools for programming and engineering, all a natural fit for the typical Acorn user. And, while the Archimedes was never likely to become the first choice for pure game lovers, a fair number of popular games did get ported. After all, even boffins and educators — or, perhaps more likely, their students — liked to indulge in a bit of pure fun sometimes.

In April of 1989, after almost two long, frustrating years of delays, Acorn released a revision of Arthur comprehensive enough to be given a whole new name. The new RISC OS incorporated many if not all of the original ambitions for ARX, at last providing the Archimedes with an attractive modern operating system worthy of its hardware. But by then, of course, it was far too late to capture the buzz a more complete Archimedes package might have garnered at its launch back in 1987.

Much to the frustration of many of their most loyal customers, Acorn still seemed not so much inept at marketing their wares to the common person as completely disinterested in doing so. It was as if they felt themselves somehow above it all. Perhaps they had taken a lesson from their one earlier attempt to climb down from their ivory tower and sell a computer for the masses. That attempt had taken the form of the Acorn Electron, a cut-down version of the BBC Micro released in 1983 as a direct competitor to the Sinclair Spectrum. Poor sales and overproduction of the Electron had been the biggest single contributor to Acorn’s mid-decade financial collapse and the loss of their independence to Olivetti. Having survived that trauma (after a fashion), Acorn seemed content to tinker away with technology for its own sake and to let the chips fall where they would when it came to actually selling the stuff that resulted.

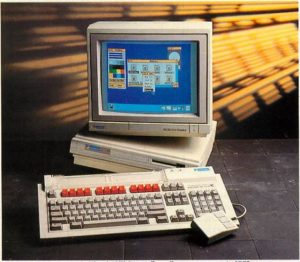

If it provided any comfort to frustrated Acorn loyalists, Amstrad also began to seem more and more at sea after their triumphant first couple of years in the computer market. In September of 1986, they added a fourth line of computers to their catalog with the release of the PC — as opposed to PCW — range. The first IBM clones targeted at the British mass market, the Amstrad PC line might have played a role in its homeland similar to that of the Tandy 1000 in the United States, popularizing these heretofore business-centric machines among home users. As usual with Amstrad, the price certainly looked right for the task. The cheapest Amstrad PC model, with a generous 512 K of memory but no hard drive, cost £399; the most expensive, which included a 20 Mb hard drive, £949. Before the Amstrad PC’s release, the cheapest IBM clone on the British market had retailed for £1429.

But, while not a flop, the PC range never took off quite as meteorically as some had expected. For months the line was dogged by reports of overheating brought on by the machine’s lack of a fan (shades of the Apple III fiasco) that may or may not have had a firm basis in fact. Alan Sugar himself was convinced that the reports could be traced back to skulduggery by IBM and other clone manufacturers trying to torpedo his cheaper machines. When he finally bowed to the pressure to add a fan, he did so as gracelessly as imaginable.

I’m a realistic person and we are a marketing organization, so if it’s the difference between people buying the machine or not, I’ll stick a bloody fan in it. And if they say they want bright pink spots on it, I’ll do that too. What is the use of me banging my head against a brick wall and saying, “You don’t need the damn fan, sunshine?”

But there were other problems as well, problems that were less easily fixed. Amstrad struggled to source hard disks, which had proved a far more popular option than expected, resulting in huge production backlogs on many models. And, worst of all, they found that they had finally overreached themselves by setting the prices too low to be realistically sustainable; prices began to creep upward almost immediately.

For that matter, prices were creeping upward across Amstrad’s entire range of computers. In 1986, after years of controversy over the alleged dumping of memory chips into the international market on the part of the Japanese semiconductor industry, the United States pressured Japan into signing a trade pact that would force them to throttle back their production and increase their prices. Absent the Japanese deluge, however, there simply weren’t enough memory chips being made in the world to fill an ever more voracious demand. By 1988, the situation had escalated into a full-blown crisis for volume computer manufacturers like Amstrad, who couldn’t find enough memory chips to build all the computers their customers wanted — and certainly not at the prices their customers were used to paying for them. Amstrad’s annual sales declined for the first time in a long time in 1988 after they were forced to raise prices and cut production dramatically due to the memory shortage. Desperate to secure a steady supply of chips so he could ramp up production again, Sugar bought into Micron Technology, one of only two American firms making memory chips, in October of 1988 to the tune of £45 million. But within a year the memory-chip crisis, anticipated by virtually everyone at the time of the Micron buy-in to go on for years yet, petered out when factories in other parts of Asia began to come online with new technologies to produce memory chips more cheaply and quickly than ever. Micron’s stock plummeted, another major loss for Amstrad. The buy-in hadn’t been “the greatest deal I’ve ever done,” admitted Sugar.

Many saw in the Amstrad of these final years of the 1980s an all too typical story in business: that of a company that had been born and grown wildly as a cult of personality around its founder, until one day it got too big for any one man to oversee. The founder’s vision seemed to bleed away as the middle managers and the layers of bureaucracy moved in. Seduced by the higher profit margins enjoyed by business computers, Amstrad strayed ever further from Sugar’s old target demographic. New models in the PC range crept north of £1000, even £2000 for the top-of-the-line machines, while the more truck-driver-focused PCW and CPC lines were increasingly neglected. The CPC line would be discontinued entirely in 1990, leaving only the antique Spectrum to soldier on for a couple more years for Amstrad in the role of general-purpose home computer. It seemed that Amstrad at some fundamental level didn’t really know how to go about producing a brand new machine in the spirit of the CPC in this era when making a new home computer was much more complicated than plugging together some off-the-shelf chips and hiring a few hackers to knock out a BASIC for the thing. Amstrad would continue to make computers for many years to come, but by the time the 1990s dawned their brief-lived glory days of 60 percent market share were already fading into the rosy glow of nostalgia.

For all their very real achievements over the course of a very remarkable decade in British computing, Acorn and Amstrad each had their own unique blind spot that kept them from achieving even more. In the Archimedes, Acorn had a machine that was a match for any other microcomputer in the world in any application you cared to name, from games to business to education. Yet they released it in half-baked form at too high a price, then failed to market it properly. In their various ranges, Amstrad had the most comprehensive lineup of computers of anyone in Britain during the mid- to late-1980s. Yet they lacked the corporate culture to imagine what people would want five years from now in addition to what they wanted today. The world needs visionaries and commodifiers alike. What British computing lacked in the 1980s was a company capable of integrating the two.

That lack left wide open a huge gap in the market: space for a next-generation home computer with a lot more power and much better graphics and sound than the likes of the old Sinclair Spectrum, but that still wouldn’t cost a fortune. Packaged, priced, and marketed differently, the Archimedes might have been that machine. As it was, buyers looked to foreign companies to provide. Neglected as Europe still was by the console makers of Japan, the British punters’ choice largely came down to one of two American imports, the Commodore Amiga and the Atari ST. Both — especially the former — would live very well in this gap that neither Acorn nor Amstrad deigned to fill for too long. Acorn did belatedly try with the release of the Archimedes A3000 model in mid-1989 — laid out in the all-in-one-case, disk-drive-on-the-side fashion of an Amiga 500, styled to resemble the old BBC Micro, and priced at a more reasonable if still not quite reasonable enough £745. But by that time the Archimedes’s fate as a boutique computer for the wealthy, the dedicated, and the well-connected was already decided. As the decade ended, an astute observer could already detect that the wild and woolly days of British computing as a unique culture unto itself were numbered.

And that would be that, but for one detail: the fairly earth-shattering detail of ARM. The ARM CPU’s ability to get extraordinary performance out of a relatively low clock speed had a huge unintended benefit that was barely even noticed by Acorn when they were in the process of designing it. In the world of computer engineering, higher clock speeds translate quite directly into higher power usage. Thus the ARM chip could do more with less power, a quality that, along with its cheapness and simplicity, made it the ideal choice for an emerging new breed of mobile computing devices. In 1990 Apple Computer, hard at work on a revolutionary “personal digital assistant” called the Newton, came calling on Acorn. A new spinoff was formed in November of 1990, a partnership among Acorn, Apple, and the semiconductor firm VLSI Technology, who had been fabricating Acorn’s ARM chips from the start. Called simply ARM Holdings, it was intended as a way to popularize the ARM architecture, particularly in the emerging mobile space, among end-user computer manufacturers like Apple who might be leery of buying ARM chips directly from a direct competitor like Acorn.

And popularize it has. To date about ten ARM CPUs have been made for every man, woman, and child on the planet, and the numbers look likely to continue to soar almost exponentially for many years to come. ARM CPUs are found today in more than 95 percent of all mobile phones. Throw in laptops (even laptops built around Intel processors usually boast several ARM chips as well), tablets, music players, cameras, GPS units… well, you get the picture. If it’s portable and it’s vaguely computery, chances are there’s an ARM inside. ARM, the most successful CPU architecture the world has ever known, looks likely to continue to thrive for many, many years to come, a classic example of unintended consequences and unintended benefits in engineering. Not a bad legacy for an era, is it?

(Sources: the book Sugar: The Amstrad Story by David Thomas; Acorn User of July 1985, October 1985, March 1986, September 1986, November 1986, June 1987, August 1987, September 1987, October 1988, November 1988, December 1988, February 1989, June 1989, and December 1989; Byte of November 1984; 8000 Plus of October 1986; Amstrad Action of November 1985; interviews with Hermann Hauser, Sophie Wilson, and Steve Furber at the Computer History Museum.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Roger Wilson now lives as Sophie Wilson. As per my usual editorial policy on these matters, I refer to her as “he” and by her original name only to avoid historical anachronisms and to stay true to the context of the times. |

|---|