A group of engineers from Commodore dropped in unannounced on the monthly meeting of the San Diego Amiga Users Group in April of 1988. They said they were on their way to West Germany with some important new technology to share with their European colleagues. With a few hours to spare before they had to catch their flight, they’d decided to share it with the user group’s members as well.

They had with them nothing less than the machine that would soon be released as the next-generation Amiga: the Amiga 3000. From the moment they powered it up to display the familiar Workbench startup icon re-imagined as a three-dimensional ray-traced rendering, the crowd was in awe. The new model sported a 68020 processor running at more than twice the clock speed of the old 68000, with a set of custom chips redesigned to match its throughput; graphics in 2 million colors instead of 4096, shown at non-interlaced — read, non-flickering — resolutions of 640 X 400 and beyond; an AmigaOS 2.0 Workbench that looked far more professional than the garish version 1.3 that was shipping with current Amigas. The crowd was just getting warmed up when the team said they had to run. They did, after all, have a plane to catch.

Word spread like crazy over the online services. Calls poured in to Commodore’s headquarters in West Chester, Pennsylvania, but they didn’t seem to know what any of the callers were talking about. Clearly this must be a very top-secret project; the engineering team must have committed a major breach of protocol by jumping the gun as they had. Who would have dreamed that Commodore was already in the final stages of a project which the Amiga community had been begging them just to get started on?

Who indeed? The whole thing was a lie. The tip-off was right there in the April date of the San Diego Users Group Meeting. The president of the group, along with a few co-conspirators, had taken a Macintosh II motherboard and shoehorned it into an Amiga 2000 case. They’d had “Amiga 3000” labels typeset and stuck them on the case, and created some reasonable-looking renderings of Amiga applications, just enough to get them through the brief amount of time their team of “Commodore engineers” — actually people from the nearby Los Angeles Amiga Users Group — would spend presenting the package. When the truth came out, some in the Amiga community congratulated the culprits for a prank well-played, while others were predictably outraged. What hurt more than the fact that they had been fooled was the reality that a Macintosh that was available right now had been able to impersonate an Amiga that existed only in their dreams. If that wasn’t an ominous sign for their favored platform’s future, it was hard to say what would be.

Of course, this combination of counterfeit hardware and sketchy demos, no matter how masterfully acted before the audience, couldn’t have been all that convincing to a neutral observer with a modicum of skepticism. Like all great hoaxes, this one succeeded because it built upon what its audience already desperately wanted to believe. In doing so, it inadvertently provided a preview of what it would mean to be an Amiga user in the future: an ongoing triumph of hope over hard-won experience. It’s been said before that the worst thing you can do is to enter into a relationship in the hope that you will be able to change the other party. Amiga users would have reason to learn that lesson over and over again: Commodore would never change. Yet many would never take the lesson to heart. To be an Amiga user would be always to be fixated upon the next shiny object out there on the horizon, always to be sure this would be the thing that would finally turn everything around, only to be disappointed again and again.

Hoaxes aside, rumors about the Amiga 3000 had been swirling around since the introduction of the 500 and 2000 models in 1987. But for a long time a rumor was all the new machine was, even as the MS-DOS and Macintosh platforms continued to evolve apace. Commodore’s engineering team was dedicated and occasionally brilliant, but their numbers were tiny in comparison to those of comparable companies, much less bigger ones like Apple and IBM, the latter of whose annual research budget was greater than Commodore’s total sales. And Commodore’s engineers were perpetually underpaid and underappreciated by their managers to boot. The only real reason for a top-flight engineer to work at Commodore was love of the Amiga itself. In light of the conditions under which they were forced to work, what the engineering staff did manage to accomplish is remarkable.

After the crushing disappointment that had been the 1989 Christmas season, when Commodore’s last and most concerted attempt to break the Amiga 500 into the American mainstream had failed, it didn’t take hope long to flower again in the new year. “The chance for an explosive Amiga market growth is still there,” wrote Amazing Computing at that time, in a line that could have summed up the sentiment of every issue they published between 1986 and 1994.

Still, reasons for optimism seemingly did still exist. For one thing, Commodore’s American operation had another new man in charge, an event which always brought with it the hope that the new boss might not prove the same as the old boss. Replacing the unfortunately named Max Toy was Harold Copperman, a real, honest-to-goodness computer-industry veteran, coming off a twenty-year stint with IBM, followed by two years with Apple; he had almost literally stepped offstage from the New York Mac Business Expo, where he had introduced John Sculley to the speaker’s podium, and into his new office at Commodore. With the attempt to pitch the Amiga 500 to low-end users as the successor to the Commodore 64 having failed to gain any traction, the biggest current grounds for optimism was that Copperman, whose experience was in business computers, could make inroads into that market for the higher-end Amiga models. Rumor had it that the dismissal of Toy and the hiring of Copperman had occurred following a civil war that had riven the company, with one faction — Toy apparently among them — saying Commodore should de-emphasize the Amiga in favor of jumping on the MS-DOS bandwagon, while the other faction saw little future — or, perhaps better said, little profit margin — in becoming just another maker of commodity clones. If you were an Amiga fan, you could at least breathe a sigh of relief that the right side had won out in that fight.

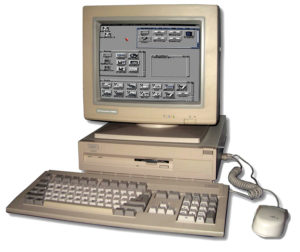

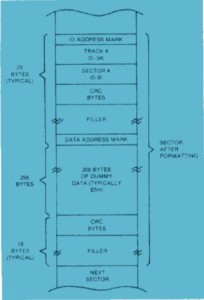

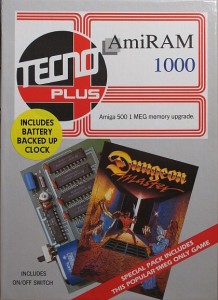

It was in that hopeful spring of 1990 that the real Amiga 3000, a machine custom-made for the high-end market, made its bow. It wasn’t a revolutionary update to the Amiga 2000 by any means, but it did offer some welcome enhancements. In fact, it bore some marked similarities to the hoax Amiga 3000 of 1988. For instance, replacing the old 68000 was a 32-bit 68030 processor, and replacing AmigaOS 1.3 was the new and much-improved — both practically and aesthetically — AmigaOS 2.0. The flicker of the interlaced graphics modes could finally be a thing of the past, at least if the user sprang for the right type of monitor, and a new “super-high resolution” mode of 1280 X 400 was available, albeit with only four onscreen colors. The maximum amount of “chip memory” — memory that could be addressed by the machine’s custom chips, and thus could be fully utilized for graphics and sound — had already increased from 512 K to 1 MB with the release of a “Fatter Agnus” chip, which could be retrofitted into older examples of the Amiga 500 and 2000, in 1989. Now it increased to 2 MB with the Amiga 3000.

So, yes, the Amiga 3000 was very welcome, as was any sign of technological progress. Yet it was also hard not to feel a little disappointed that, five years after the unveiling of the first Amiga, the platform had only advanced this far. The hard fact was that Commodore’s engineers, forced to work on a shoestring as they were, were still tinkering at the edges of the architecture that Jay Miner and his team had devised all those years before rather than truly digging into it to make the more fundamental changes that were urgently needed to keep up with the competition. The interlace flicker was eliminated, for instance, not by altering the custom chips themselves but by hanging an external “flicker fixer” onto the end of the bus to de-interlace the interlaced output they still produced before it reached the monitor. And the custom chips still ran no faster than they had in the original Amiga, meaning the hot new 68030 had to slow down to a crawl every time it needed to access the chip memory it shared with them. The color palette remained stuck at 4096 shades, and, with the exception of the new super-high resolution mode, whose weirdly stretched pixels and four colors limited its usability, the graphics modes as a whole remained unchanged. Amiga owners had spent years mocking the Apple Macintosh and the Atari ST for their allegedly unimaginative, compromised designs, contrasting them continually with Jay Miner’s elegant dream machine. Now, that argument was getting harder to make; the Amiga too was starting to look a little compromised and inelegant.

Harold Copperman personally introduced the Amiga 3000 in a lavish event — lavish at least by Commodore’s standards — held at New York City’s trendy Palladium nightclub. With CD-ROM in the offing and audiovisual standards improving rapidly across the computer industry, “multimedia” stood with the likes of “hypertext” as one of the great buzzwords of the age. Commodore was all over it, even going so far as to name the event “Multimedia Live!” From Copperman’s address:

It’s our turn. It’s our time. We had the technology four and a half years ago. In fact, we had the product ready for multimedia before multimedia was ready for a product. Today we’re improving the technology, and we’re in the catbird seat. It is our time. It is Commodore’s time.

I’m at Commodore just as multimedia becomes the most important item in the marketplace. Once again I’m with the leader. Of course, in this industry a leader doesn’t have any followers; he just has a lot of other companies trying to pass him by. But take a close look: the other companies are talking multimedia, but they’re not doing it. They’re a long way behind Commodore — not even close.

Multimedia is a first-class way for conveying a message because it takes the strength of the intellectual content and adds the verve — the emotion-grabbing, head-turning, pulse-raising impact that comes from great visuals plus a dynamic soundtrack. For everyone with a message to deliver, it unleashes extraordinary ability. For the businessman, educator, or government manager, it turns any ordinary meeting into an experience.

In a way, this speech was cut from the same cloth as the Amiga 3000 itself. It was certainly a sign of progress, but was it progress enough? Even as he sounded more engaged and more engaging than had plenty of other tepid Commodore executives, Copperman inadvertently pointed out much of what was still wrong with the organization he helmed. He was right that Commodore had had the technology to do multimedia for a long time; as I’ve argued at length elsewhere, the Amiga was in fact the world’s first multimedia personal computer, all the way back in 1985. Still, the obvious question one is left with after reading the first paragraph of the extract above is why, if Commodore had the technology to do multimedia four and a half years ago, they’ve waited until now to tell anyone about it. In short, why is the world of 1990 “ready” for multimedia when the world of 1985 wasn’t? Contrary to Copperman’s claim about being a leader, Commodore’s own management had begun to evince an understanding of what the Amiga was and what made it special only after other companies had started building computers similar to it. Real business leaders don’t wait around for the world to decide it’s ready for their products; they make products the world doesn’t yet know it needs, then tell it why it needs them. Five years after being gifted with the Amiga, which stands alongside the Macintosh as one of the two most visionary computers of the 1980s precisely because of its embrace of multimedia, Commodore managed at this event to give every impression that they were the multimedia bandwagon jumpers.

The Amiga 3000 didn’t turn into the game changer the faithful were always dreaming of. It sold moderately, mostly to the established Amiga hardcore, but had little obvious effect on the platform’s overall marketplace position. Harold Copperman was blamed for the disappointment, and was duly fired by Irving Gould, the principal shareholder and ultimate authority at Commodore, at the beginning of 1991. The new company line became an exact inversion of that which had held sway at the time of the Amiga 3000’s introduction: Copperman’s expertise was business computing, but Commodore’s future lay in consumer computing. Jim Dionne, head of Commodore’s Canadian division and supposedly an expert consumer marketer, was brought in to replace him.

An old joke began to make the rounds of the company once again. A new executive arrives at his desk at Commodore and finds three envelopes in the drawer, each labelled “open in case of emergency” and numbered one, two, and three. When the company gets into trouble for the first time on his watch, he opens the first envelope. Inside is a note: “Blame your predecessor.” So he does, and that saves his bacon for a while, but then things go south again. He opens the second envelope: “Blame your vice-presidents.” So he does, and gets another lease on life, but of course it only lasts a little while. He opens the third envelope. “Prepare three envelopes…” he begins to read.

Yet anyone who happened to be looking closely might have observed that the firing of Copperman represented something more than the usual shuffling of the deck chairs on the S.S. Commodore. Upon his promotion, it was made clear to Jim Dionne that he was to be held on a much shorter leash than his predecessors, his authority carefully circumscribed. Filling the power vacuum was one Mehdi Ali, a lawyer and finance guy who had come to Commodore a couple of years before as a consultant and had since insinuated himself more and more with Irving Gould. Now he advanced to the title of president of Commodore International, Gould’s right-hand man in running the global organization; indeed, he seemed to be calling far more shots these days than his globe-trotting boss, who never seemed to be around when you needed him anyway. Ali’s rise would not prove a happy event for anyone who cared about the long-term health of the company.

For now, though, the full import of the changes in Commodore’s management structure was far from clear. Amiga users were on to the next Great White Hope, one that in fact had already been hinted at in the Palladium as the Amiga 3000 was being introduced. Once more “multimedia” would be the buzzword, but this time the focus would go back to the American consumer market Commodore had repeatedly failed to capture with the Amiga 500. The clue had been there in a seemingly innocuous, almost throwaway line from the speech delivered to the Palladium crowd by C. Lloyd Mahaffey, Commodore’s director of marketing: “While professional users comprise the majority of the multimedia-related markets today, future plans call for penetration into the consumer market as home users begin to discover the benefits of multimedia.”

Commodore’s management, (proud?) owners of the world’s first multimedia personal computer, had for most of the latter 1980s been conspicuous by their complete disinterest in their industry’s initial forays into CD-ROM, the storage medium that, along with the graphics and sound hardware the Amiga already possessed, could have been the crowning piece of the platform’s multimedia edifice. The disinterest persisted in spite of the subtle and eventually blatant hints that were being dropped by people like Cinemaware’s Bob Jacob, whose pioneering “interactive movies” were screaming to be liberated from the constraints of 880 K floppy disks.

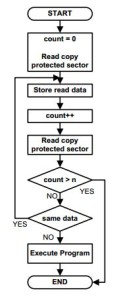

In 1989, a tiny piece of Commodore’s small engineering staff — described as “mavericks” by at least one source — resolved to take matters into their own hands, mating an Amiga with a CD-ROM drive and preparing a few demos designed to convince their managers of the potential that was being missed. Management was indeed convinced by the demo — but convinced to go in a radically different direction from that of simply making a CD-ROM drive that could be plugged into existing Amigas.

The Dutch electronics giant Philips had been struggling for what seemed like forever to finish something they envisioned as a whole new category of consumer electronics: a set-top box for the consumption of interactive multimedia content on CD. They called it CD-I, and it was already very, very late. Originally projected for release in time for the Christmas of 1987, its constant delays had left half the entertainment-software industry, who had invested heavily in the platform, in limbo on the whole subject of CD-ROM. What if Commodore could steal Philips’s thunder by combining a CD-ROM drive with the audiovisually capable Amiga architecture not in a desktop computer but in a set-top box of their own? This could be the magic bullet they’d been looking for, the long-awaited replacement for the Commodore 64 in American living rooms.

The industry’s fixation on these CD-ROM set-top boxes — a fixation which was hardly confined to Philips and Commodore alone — perhaps requires a bit of explanation. One thing these gadgets were not, at least if you listened to the voices promoting them, was game consoles. The set-top boxes could be used for many purposes, from displaying multimedia encyclopedias to playing music CDs. And even when they were used for pure interactive entertainment, it would be, at least potentially, adult entertainment (a term that was generally not meant in the pornographic sense, although some were already muttering about the possibilities that lurked therein as well). This was part and parcel of a vision that came to dominate much of digital entertainment between about 1989 and 1994: that of a sort of grand bargain between Northern and Southern California, a melding of the new interactive technologies coming out of Silicon Valley with the movie-making machine of Hollywood. Much of television viewing, so went the argument, would become interactive, the VCR replaced with the multimedia set-top box.

In light of all this conventional wisdom, Commodore’s determination to enter the fray — effectively to finish the job that Philips couldn’t seem to — can all too easily be seen as just another example of the me-too-ism that had clung to their earlier multimedia pronouncements. At the time, though, the project was exciting enough that Commodore was able to lure quite a number of prominent names to work with them on it. Carl Sassenrath, who had designed the core of the original AmigaOS — including its revolutionary multitasking capability — signed on again to adapt his work to the needs of a set-top box. (“In many ways, it was what we had originally dreamed for the Amiga,” he would later say of the project, a telling quote indeed.) Jim Sachs, still the most famous of Amiga artists thanks to his work on Cinemaware’s Defender of the Crown, agreed to design the look of the user interface. Reichart von Wolfsheild and Leo Schwab, both well-known Amiga developers, also joined. And for the role of marketing evangelist Commodore hired none other than Nolan Bushnell, the founder almost two decades before of Atari, the very first company to place interactive entertainment in American living rooms. The project as a whole was placed in the capable hands of Gail Wellington, known throughout the Amiga community as the only Commodore manager with a dollop of sense. The gadget itself came to be called CDTV — an acronym, Commodore would later claim in a part of the sales pitch that fooled no one, for “Commodore Dynamic Total Vision.”

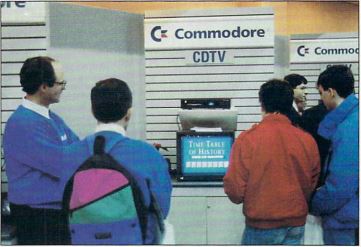

Commodore announced CDTV at the Summer Consumer Electronics Show in June of 1990, inviting selected attendees to visit a back room and witness a small black box, looking for all the world like a VCR or a stereo component, running some simple demos. From the beginning, they worked hard to disassociate the product from the Amiga and, indeed, from computers in general. The word “Amiga” appeared nowhere on the hardware or anywhere on the packaging, and if all went according to plan CDTV would be sold next to televisions and stereos in department stores, not in computer shops. Commodore pointed out that everything from refrigerators to automobiles contained microprocessors these days, but no one called those things computers. Why should CDTV be any different? It required no monitor, instead hooking up to the family television set. It neither included nor required a keyboard — much industry research had supposedly proved that non-computer users feared keyboards more than anything else — nor even a mouse, being controlled entirely through a remote control that looked pretty much like any other specimen of same one might find between the cushions of a modern sofa. “If you know how to change TV channels,” said a spokesman, “you can take full advantage of CDTV.” It would be available, Commodore claimed, before the Christmas of 1990, which should be well before CD-I despite the latter’s monumental head start.

That timeline sounded overoptimistic even when it was first announced, and few were surprised to see the launch date slip into 1991. But the extra time did allow a surprising number of developers to jump aboard the CDTV train. Commodore had never been good at developer relations, and weren’t terribly good at it now; developers complained that the tools Commodore provided were always late and inadequate and that help with technical problems wasn’t easy to come by, while financial help was predictably nonexistent. Still, lots of CD-I projects had been left in limbo by Philips’s dithering and were attractive targets for adaptation to CDTV, while the new platform’s Amiga underpinnings made it fairly simple to port over extant Amiga games like SimCity and Battle Chess. By early 1991, Commodore could point to about fifty officially announced CDTV titles, among them products from such heavy hitters as Grolier, Disney, Guinness (the publisher, not the beer company), Lucasfilm, and Sierra. This relatively long list of CDTV developers certainly seemed a good sign, even if not all of the products they proposed to create looked likely to be all that exciting, or perhaps even all that good. Plenty of platforms, including the original Amiga, had launched with much less.

While the world — or at least the Amiga world — held its collective breath waiting for CDTV’s debut, the charismatic Nolan Bushnell did what he had been hired to do: evangelize like crazy. “What we are really trying to do is make multimedia a reality, and I think we’ve done that,” he said. The hyperbole was flying thick and fast from all quarters. “This will change forever the way we communicate, learn, and entertain,” said Irving Gould. Not to be outdone, Bushnell noted that “books were great in their day, but books right now don’t cut it. They’re obsolete.” (Really, why was everyone so determined to declare the death of the book during this period?)

CDTV being introduced at the 1991 World of Amiga show. Doing the introducing is Gail Wellington, head of the CDTV project and one of the unsung heroes of Commodore.

The first finished CDTV units showed up at the World of Amiga show in New York City in April of 1991; Commodore sold their first 350 to the Amiga faithful there. A staggered roll-out followed: to five major American cities, Canada, and the Commodore stronghold of Britain in May; to France, Germany, and Italy in the summer; to the rest of the United States in time for Christmas. With CD-I now four years late, CDTV thus became the first CD-ROM-based set-top box you could actually go out and buy. Doing so would set you back just under $1000.

The Amiga community, despite being less than thrilled by the excision of all mention of their platform’s name from the product, greeted the launch with the same enthusiasm they had lavished on the Amiga 3000, their Great White Hope of the previous year, or for that matter the big Christmas marketing campaign of 1989. Amazing Computing spoke with bated breath of CDTV becoming the “standard for interactive multimedia consumer hardware.”

Alas, there followed a movie we’ve already seen many times. Commodore’s marketing was ham-handed as usual, declaring CDTV “nothing short of revolutionary” but failing to describe in clear, comprehensible terms why anyone who was more interested in relaxing on the sofa than fomenting revolutions might actually want one. The determination to disassociate CDTV from the scary world of computers was so complete that the computer magazines weren’t even allowed advance models; Amiga Format, the biggest Amiga magazine in Britain at the time with a circulation of more than 160,000, could only manage to secure their preview unit by making a side deal with a CDTV developer. CDTV units were instead sent to stereo magazines, who shrugged their shoulders at this weird thing this weird computer company had sent them and returned to reviewing the latest conventional CD players. Nolan Bushnell, the alleged marketing genius who was supposed to be CDTV’s ace in the hole, talked a hyperbolic game at the trade shows but seemed otherwise disengaged, happy just to show up and give his speeches and pocket his fat paychecks. One could almost suspect — perish the thought! — that he had only taken this gig for the money.

In the face of all this, CDTV struggled mightily to make any headway at all. When CD-I hit the market just before Christmas, boasting more impressive hardware than CDTV for roughly the same price, it only made the hill that much steeper. Commodore now had a rival in a market category whose very existence consumers still obstinately refused to recognize. As an established maker of consumer electronics in good standing with the major retailers — something Commodore hadn’t been since the heyday of the Commodore 64 — Philips had lots of advantages in trying to flog their particular white elephant, not to mention an advertising budget their rival could only dream of. CD-I was soon everywhere, on store shelves and in the pages of the glossy lifestyle magazines, while CDTV was almost nowhere. Commodore did what they could, cutting the list price of CDTV to less than $800 and bundling with it The New Grolier Encyclopedia and the smash Amiga game Lemmings. It didn’t help. After an ugly Christmas season, Nolan Bushnell and the other big names all deserted the sinking ship.

Even leaving aside the difficulties inherent in trying to introduce people to an entirely new category of consumer electronics — difficulties that were only magnified by Commodore’s longstanding marketing ineptitude — CDTV had always been problematic in ways that had been all too easy for the true believers to overlook. It was clunky in comparison to CD-I, with a remote control that felt awkward to use, especially for games, and a drive which required that the discs first be placed into an external holder before being loaded into the unit proper. More fundamentally, the very re-purposing of old Amiga technology that had allowed it to beat CD-I to market made it an even more limited platform than its rival for running the sophisticated adult entertainments it was supposed to have enabled. Much of the delay in getting CD-I to market had been the product of a long struggle to find a way of doing video playback with some sort of reasonable fidelity. Even the released CD-I performed far from ideally in this area, but it did better than CDTV, which at best — at best, mind you — might be able to fill about a third of the television screen with low-resolution video running at a choppy twelve frames per second. It was going to be hard to facilitate a union of Silicon Valley and Hollywood with technology like that.

None of CDTV’s problems were the fault of the people who had created it, who had, like so many Commodore engineers before and after them, been asked to pull off a miracle on a shoestring. They had managed to create, if not quite a miracle, something that worked far better than it had a right to. It just wasn’t quite good enough to overcome the marketing issues, the competition from CD-I, and the marketplace confusion engendered by an interactive set-top box that said it wasn’t a game console but definitely wasn’t a home computer either.

CDTV could be outfitted with a number of accessories that turned it into more of a “real” computer. Still, those making software for the system couldn’t count on any of these accessories being present, which served to greatly restrict their products’ scope of possibility.

Which isn’t to say that some groundbreaking work wasn’t done by the developers who took a leap of faith on Commodore — almost always a bad bet in financial terms — and produced software for the platform. CDTV’s early software catalog was actually much more impressive than that of CD-I, whose long gestation had caused so many initially enthusiastic developers to walk away in disgust. The New Grolier Encyclopedia was a true multimedia dictionary; the entry for John F. Kennedy, for example, included not only a textual biography and photos to go along with it but audio excerpts from his most famous speeches. The American Heritage Dictionary also offered images where relevant, along with an audio pronunciation of every single word. American Vista: The Multimedia U.S. Atlas boasted lots of imagery of its own to add flavor to its maps, and could plan a route between any two points in the country at the click of a button. All of these things may sound ordinary today, but in a way that very modern ordinariness is a testament to what pioneering products these really were. They did in fact present an argument that, while others merely talked about the multimedia future, Commodore through CDTV was doing it — imperfectly and clunkily, yes, but one has to start somewhere.

One of the most impressive CDTV titles of all marked the return of one of the Amiga’s most beloved icons. After designing the CDTV’s menu system, the indefatigable Jim Sachs returned to the scene of his most famous creation. Really a remake rather than a sequel, Defender of the Crown II reintroduced many of the additional graphics and additional tactical complexities that had been excised from the original in the name of saving time, pairing them with a full orchestral soundtrack, digitized sound effects, and a narrator to detail the proceedings in the appropriate dulcet English accent. It was, Sachs said, “the game the original Defender of the Crown was meant to be, both in gameplay and graphics.” He did almost all of the work on this elaborate multimedia production all by himself, farming out little more than the aforementioned narration, and Commodore themselves released the game, having acquired the right to do so from the now-defunct Cinemaware at auction. While, as with the original, its long-term play value is perhaps questionable, Defender of the Crown II even today still looks and sounds mouth-wateringly gorgeous.

If any one title on CDTV was impressive enough to sell the machine by itself, this ought to have been it. Unfortunately, it didn’t appear until well into 1992, by which time CDTV already had the odor of death clinging to it. The very fact that Commodore allowed the game to be billed as the sequel to one so intimately connected to the Amiga’s early days speaks to a marketing change they had instituted to try to breathe some life back into the platform.

The change was born out of an insurrection staged by Commodore’s United Kingdom branch, who always seemed to be about five steps ahead of the home office in any area you cared to name. Kelly Sumner, managing director of Commodore UK:

We weren’t involved in any of the development of CDTV technology; that was all done in America. We were taking the lead from the corporate company. And there was a concrete stance of “this is how you promote it, this is the way forward, don’t do this, don’t do that.” So, that’s what we did.

But after six or eight months we basically turned around and said, “You don’t know what you’re talking about. It ain’t going to go anywhere, and if it does go anywhere you’re going to have to spend so much money that it isn’t worth doing. So, we’re going to call it the Amiga CDTV, we’re going to produce a package with disk drives and such like, and we’re going to promote it like that. People can understand that, and you don’t have to spend so much money.”

True to their word, Commodore UK put together what they called “The Multimedia Home Computer Pack,” combining a CDTV unit with a keyboard, a mouse, an external disk drive, and the software necessary to use it as a conventional Amiga as well as a multimedia appliance — all for just £100 more than a CDTV unit alone. Commodore’s American operation grudgingly followed their lead, allowing the word “Amiga” to creep back into their presentations and advertising copy.

But it was too late — and not only for CDTV but in another sense for the Amiga platform itself. The great hidden cost of the CDTV disappointment was the damage it did to the prospects for CD-ROM on the Amiga proper. Commodore had been so determined to position CDTV as its own thing that they had rejected the possibility of equipping Amiga computers as well with CD-ROM drives, despite the pleas of software developers and everyday customers alike. A CD-ROM drive wasn’t officially mated to the world’s first multimedia personal computer until the fall of 1992, when, with CDTV now all but left for dead, Commodore finally started shipping an external drive that made it possible to run most CDTV software, as well as CD-based software designed specifically for Amiga computers, on an Amiga 500. Even then, Commodore provided no official CD-ROM solution for Amiga 2000 and 3000 owners, forcing them to cobble together third-party adapters that could interface with drives designed for the Macintosh. The people who owned the high-end Amiga models, of course, were the ones working in the very cutting-edge fields that cried out for CD-ROM.

It’s difficult to overstate the amount of damage the Amiga’s absence from the CD-ROM party, the hottest ticket in computing at the time, did to the platform’s prospects. It single-handedly gave the lie to every word in Harold Copperman’s 1990 speech about Commodore being “the leaders in multimedia.” Many of the most vibrant Amiga developers were forced to shift to the Macintosh or another platform by the lack of CD-ROM support. Of all Commodore’s failures, this one must loom among the largest. They allowed the Macintosh to become the platform most associated with the new era of CD-ROM-enabled multimedia computing without even bothering to contest the territory. The war was over before Commodore even realized a war was on.

Commodore’s feeble last gasp in terms of marketing CDTV positioned it as essentially an accessory to desktop Amigas, a “low-cost delivery system for multimedia” targeted at business and government rather than living rooms. The idea was that you could create presentations on Amiga computers, send them off to be mastered onto CD, then drag the CDTV along to board meetings or planning councils to show them off. In that spirit, a CDTV unit was reduced to a free toss-in if you bought an Amiga 3000 — two slow-selling products that deserved one another.

The final verdict on CDTV is about as ugly as they come: less than 30,000 sold worldwide in some eighteen months of trying; less than 10,000 sold in the American market Commodore so desperately wanted to break back into, and many or most of those sold at fire-sale discounts after the platform’s fate was clear. In other words, the 350 CDTV units that had been sold to the faithful at that first ebullient World of Amiga show made up an alarmingly high percentage of all the CDTV units that would ever sell. (Philips, by contrast, would eventually manage to move about 1 million CD-I units over the course of about seven years of trying.)

The picture I’ve painted of the state of Commodore thus far is a fairly bleak one. Yet that bleakness wasn’t really reflected in the company’s bottom line during the first couple of years of the 1990s. For all the trouble Commodore had breaking new products in North America and elsewhere, their legacy products were still a force to be reckoned with outside the United States. Here the end of the Cold War and subsequent lifting of the Iron Curtain proved a boon. The newly liberated peoples of Eastern Europe were eager to get their hands on Western computers and computer games, but had little money to spend on them. The venerable old Commodore 64, pulling along behind it that rich catalog of thousands upon thousands of games of all stripes, was the perfect machine for these emerging markets. Effectively dead in North America and trending that way in Western Europe, it now enjoyed a new lease on life in the former Soviet sphere, its sales numbers suddenly climbing sharply again instead of falling. The Commodore 64 was, it seemed, the cockroach of computers; you just couldn’t kill it. Not that Commodore wanted to: they would happily bank every dollar their most famous creation could still earn them. Meanwhile the Amiga 500 was selling better than ever in Western Europe, where it was now the most popular single gaming platform of all, and Commodore happily banked those profits as well.

Commodore’s stock even enjoyed a brief-lived bubble of sorts. In the spring and early summer of 1991, with sales strong all over Europe and CDTV poised to hit the scene, the stock price soared past $20, stratospheric heights by Commodore’s recent standards. This being Commodore, the stock collapsed below $10 again just as quickly — but, hey, it was nice while it lasted. In the fiscal year ending on June 30, 1991, worldwide sales topped the magical $1 billion mark, another height that had last been seen in the heyday of the Commodore 64. Commodore was now the second most popular maker of personal computers in Europe, with a market share of 12.4 percent, just slightly behind IBM’s 12.7 percent. The Amiga was now selling at a clip of 1 million machines per year, which would bring the total installed base to 4.5 million by the end of 1992. Of that total, 3.5 million were in Europe: 1.3 million in Germany, 1.2 million in Britain, 600,000 in Italy, 250,000 in France, 80,000 in Scandinavia. (Ironically in light of the machine’s Spanish name, one of the few places in Western Europe where it never did well at all was Spain.) To celebrate their European success, Irving Gould and Mehdi Ali took home salaries in 1991 of $1.75 million and $2.4 million respectively, the latter figure $400,000 more than the chairman of IBM, a company fifty times Commodore’s size, was earning.

But it wasn’t hard to see that Commodore, in relying on all of these legacy products sold in foreign markets, was living on borrowed time. Even in Europe, MS-DOS was beginning to slowly creep up on the Amiga as a gaming platform by 1992, while Nintendo and Sega, the two big Japanese console makers, were finally starting to take notice of this virgin territory after having ignored it for so long. While Amiga sales in Europe in 1992 remained blessedly steady, sales of the Amiga in North America were down as usual, sales of the Commodore 64 in Eastern Europe fell off thanks to economic chaos in the region, and sales of Commodore’s line of commodity PC clones cratered so badly that they pulled out of that market entirely. It all added up to a bottom line of about $900 million in total earnings for the fiscal year ending on June 30, 1992. The company was still profitable, but considerably less so than it had been the year before. Everyone was now looking forward to 1993 with more than a little trepidation.

Even as Commodore faced an uncertain future, they could at least take comfort that their arch-enemy Atari was having a much worse time of it. In the very early 1990s, Atari enjoyed some success, if not as much as they had hoped, with their Lynx handheld game console, a more upscale rival to the Nintendo Game Boy. The Atari Portfolio, a genuinely groundbreaking palmtop computer, also did fairly well for them, if perhaps not quite as well as it deserved. But the story of their flagship computing platform, the Atari ST, was less happy. Already all but dead in the United States, the ST’s market share in Europe shrank in proportion to the Amiga’s increasing sales, such that it fell from second to third most popular gaming computer in 1991, trailing MS-DOS now as well as the Amiga.

Atari tried to remedy the slowing sales with new machines they called the STe line, which increased the color palette to 4096 shades and added a blitter chip to aid onscreen animation. (The delighted Amiga zealots at Amazing Computing wrote of these Amiga-inspired developments that they reminded them of “an Amiga 500 created by a primitive tribe that had never actually seen an Amiga, but had heard reports from missionaries of what the Amiga could do.”) But the new hardware broke compatibility with much existing software, and it only got harder to justify buying an STe instead of an Amiga 500 as the latter’s price slowly fell. Atari’s total sales in 1991 were just $285 million, down by some 30 percent from the previous year and barely a quarter of the numbers Commodore was doing. Jack Tramiel and his sons kept their heads above water only by selling off pieces of the company, such as the Taiwanese manufacturing facility that went for $40.9 million that year. You didn’t have to be an expert in the computer business to understand how unsustainable that path was. In the second quarter of 1992, Atari posted a loss of $39.8 million on sales of just $23.3 million, a rather remarkable feat in itself. Whatever else lay in store for Commodore and the Amiga, they had apparently buried old Mr. “Business is War.”

Still, this was no time to bask in the glow of sweet revenge. The question of where Commodore and the Amiga went from here was being asked with increasing urgency in 1992, and for very good reason. The answer would arrive in the latter half of the year, in the form at long last of the real, fundamental technical improvements the Amiga community had been begging for for so long. But had Commodore done enough, and had they done it in time to make a difference? Those questions loomed large as the 68000 Wars were about to enter their final phase.

(Sources: the book On the Edge: The Spectacular Rise and Fall of Commodore by Brian Bagnall; Amazing Computing of August 1987, June 1988, June 1989, July 1989, May 1990, June 1990, July 1990, August 1990, September 1990, December 1990, January 1991, February 1991, March 1991, April 1991, May 1991, June 1991, August 1991, September 1991, November 1991, January 1992, February 1992, March 1992, April 1992, June 1992, July 1992, August 1992, September 1992, November 1992, and December 1992; Info of July/August 1988 and January/February 1989; Amiga Format of July 1991, July 1995, and the 1992 annual; The One of September 1990, May 1991, and December 1991; CU Amiga of June 1992, October 1992, and November 1992; Amiga Computing of April 1992; AmigaWorld of June 1991. Online sources include Matt Barton’s YouTube interview with Jim Sachs, Sébastien Jeudy’s interview with Carl Sassenrath, Greg Donner’s Workbench Nostalgia, and Atari’s annual reports from 1989, available on archive.org. My huge thanks to reader “himitsu” for pointing me to the last and providing some other useful information on Commodore and Atari’s financials during this period in the comments to a previous article in this series. And thank you to Reichart von Wolfsheild, who took time from his busy schedule to spend a Saturday morning with me looking back on the CDTV project.)