The idea of being in the body of a guy and making love to his wife — when she believes you’re her husband, even though you’re not — was a very strange position to be in. That’s exactly the kind of thing I try to explore in all my games today.

— David Cage, speaking from the Department of WTF

The French videogame auteur David Cage has been polarizing critics and gamers for more than a quarter-century with his oddly retro-futurist vision of the medium. He believes that games need to cease prioritizing “action” at the expense of “emotion,” a task which they can best accomplish, according to him, by embracing the aesthetics, techniques, and thematic concerns of cinema. You could lift a sentence or a paragraph from many a post-millennial David Cage interview, drop it into an article from the “interactive movie” boom of the mid-1990s, and no one would notice the difference. The interactive movie is as debatable a proposition today as it was back then; still more debatable in many cases has been Cage’s execution of it. Still, he must be doing something right: he’s been able to keep his studio Quantic Dream alive all these years, making big-budget story-focused single-player games in an industry which hasn’t always been terribly friendly toward such things.

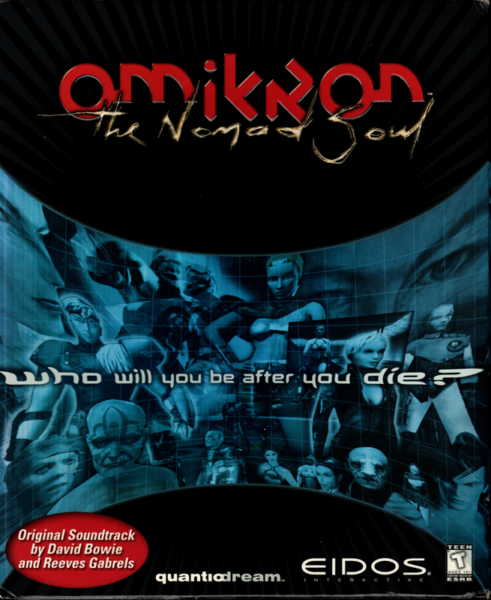

Cage’s very first and least-played game was known as simply The Nomad Soul in Europe, as Omikron: The Nomad Soul in North America; I’ll go with the latter name here, because that’s the one under which you can still find it on digital storefronts today. Released in 1999, it’s both typical and atypical of his later oeuvre. We see the same emphasis on story, the same cinematic sensibility, the same determination to eliminate conventional failure states, even the same granular obsessions with noirish law enforcement, the transmigration of souls, and, well, Blade Runner. But it’s uniquely ambitious in its gameplay, despite having been made for far less money than any other David Cage production. It’s a combination of Beneath a Steel Sky with Tomb Raider with Mortal Kombat with Quake, with a soundtrack provided by David Bowie. If you’re a rambunctious thirteen-year-old, like our old friends Ian and Nigel, you might be thinking that that sounds awesome. If you’re older and wiser, the alarm bells are probably already ringing in your head. Such cynicism is sadly warranted; no jack of all trades has ever mastered fewer of them than Omikron.

David Cage was born in 1969 as David de Gruttola, in the Alsatian border town of Mulhouse, a hop and a skip away from both Germany and Switzerland. He discovered that he had a talent for music at an early age. By the time he was fifteen, he could play piano, guitar, bass, and drums, and had started doing session gigs for studios as far away as Paris. He moved to the City of Light as soon as he finished school. By saving his earnings as a session musician, he was eventually able to buy an existing music studio there that went under the name of Totem. A competent composer as well as instrumentalist, he provided jingles for television commercials and the like. These kinds of ultra-commoditized music productions were rapidly computerizing by the end of the 1980s; it was much cheaper and faster to knock out a simple tune with a bank of keyboards and a MIDI controller than it was to hire a whole band to come in or to overdub the parts one by one on “real” instruments. Thus Totem became David de Gruttola’s entrée into the world of digital technology.

Totem also brought Gruttola into the orbit of the French games industry for the first time. He provided music and/or sound for five games between 1994 and 1996: Super Dany, Timecop, Cheese Cat-astrophe, Versailles 1685, and Hardline. Roll call of mediocrity though this list may be, it awakened a passion in him. By now in the second half of his twenties, he was still very young by most standards, but old enough to realize that he would never be more than a competent musician or composer. Games, though… games might be another story. Never one to shrink unduly from the grandiose view of himself and his art, he would describe his feelings in this way a decade later:

I remember how many possibilities suddenly opened up because of this new technology. I saw it as a new means of expression, where the world could be pushed to its limits. It was my way of exploring new horizons. I felt like a pioneer filmmaker at the start of the twentieth century: grappling with basic technology, but also being aware that there is everything left to invent — in particular, a new language that is both narrative and visual.

Thus inspired, Gruttola wrote a script of 200 to 250 pages, about a gamer who gets sucked through the monitor into an alternative universe, winding up in a futuristic dystopian city known as Omikron. The script was “naïve but sincere,” he says. “I was dreaming of a game with an open-world city where I could go wherever I wanted, meet anybody, use vehicles, fight, and transfer my soul into another body.” (Ian and Nigel would surely have approved…)

Being neither a programmer nor a visual artist himself, he convinced a handful of friends to help him out. They first tried to implement Omikron on a Sony PlayStation, only to think better of it and turn it into a Windows game instead. Late in 1996, more excited than ever, Gruttola offered his friends a contract: he would pay them to work on the game exclusively for the next six months, using the money he had made from his music business. At the end of that time, they ought to have a decent demo to shop around to publishers. If they could land one, they would be off to the races. If they couldn’t, they would put their ludic dreams away and go back to their old lives. Five of the friends agreed.

So, they made a 3D engine from scratch, then made a first pass at their Blade Runner-like city. “The demo presented an open world,” recalls Oliver Demangel, who left a position at Ubisoft to take a chance with Gruttola. “You could basically walk around in a city and have some limited interaction with the environment around you.” With the demo in hand and his six-month deadline about to expire, Gruttola started calling every publisher in Europe. Or rather “David Cage” did: realizing that his surname didn’t exactly roll off the tongue, he created the nom-de-plume by appropriating the last name of Johnny Cage, his favorite fighter from Mortal Kombat.

The British publisher Eidos, soaring at the time on the wings of Tomb Raider, invited the freshly rechristened game designer to come out to London. Cage flew back to Paris two days later with a signed development contract in hand. On May 2, 1997, Totem morphed into Quantic Dream, a games rather than a music studio. Over the following month, Cage hired another 35 people to join the five friends he had started out with and help them make Omikron: The Nomad Soul.

Games were entering a new era of mass-market cultural relevance during this period. On the other side of the English Channel, Lara Croft, the heroine of Tomb Raider, had become as much an icon of Cool Britannia as the Spice Girls, giving interviews with journalists and lending her bodacious body to glossy magazine covers, undaunted by her ultimate lack of a corporeal form. Thus when David Cage suggested looking for an established pop act to perhaps lend some music to his game, Eidos was immediately receptive to the idea. The list of possibilities that Cage and his mates provided included such contemporary hipster favorites as Björk, Massive Attack, and Archive. And it also included one name from an earlier generation: David Bowie. Bowie proved the only one to return Eidos’s call. He agreed to come to a meeting in London to hear the pitch.

More than a decade removed from the peak of his commercial success, and still further removed from the unimpeachable, genre-bending run of 1970s albums that will always be the beating heart of his musical legacy, the 1990s version of David Bowie had settled, seemingly comfortably enough, into the role of Britpop’s cool uncle. He went on tour with the likes of Nine Inch Nails and Morrissey and released new albums every other year or so that cautiously incorporated the latest sounds. If the catchy hooks and spark of spontaneity — not to mention the radio play and record sales — weren’t quite there anymore, he did deserve credit for refusing to become a nostalgia act in the way of so many of his peers.

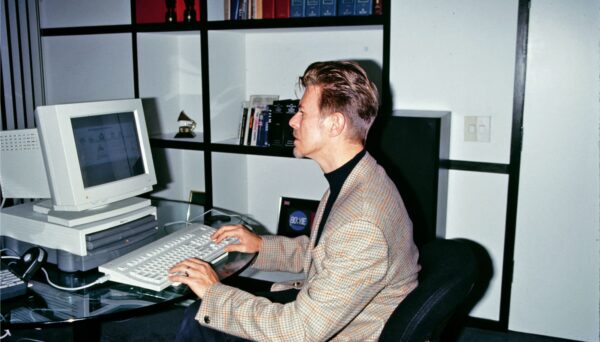

But almost more relevant than Bowie’s current music when it came to Omikron was his deep-seated fascination with the new digital society he saw springing into being around him. He had started to use a computer himself only a few years before: in 1993, when his 22-year-old son Duncan gave him an Apple Macintosh. At first, he used it mostly for playing around with graphics, but he soon found his way onto the Internet for the first time. This digital frontier struck him as a revelation. He became so addicted to surfing the Web that he had to join a support group. He seemed to understand what was coming in a way that few other technologists — never mind rock stars — could match. He became the first prominent musician to make his own website and to use it to engage directly with his fans, the first to debut a new song and its accompanying video on the Internet, the first to co-write a song with a lucky online follower. Displaying a head for business that had always been one of his more underrated qualities, he started charging fans a subscription fee for content at a time when few people other than porn purveyors were bothering to even try to make money online. By the time he took the meeting with Eidos and Quantic Dream, he was in the process of setting up BowieNet, his own Internet service provider. (Yes, really!) He had also just floated his “Bowie Bonds,” by which means his fans could help him to raise the $55 million he needed to buy his back catalog, remaster it, and re-release it as a set of deluxe CDs. From social networking to crowd-sourcing, Bowie was clearly well ahead of the curve. “I don’t even think we’ve seen the tip of the iceberg,” he would say in 2000 in a much-quoted television interview. “I think the potential of what the Internet is going to do, both good and bad, is unimaginable. I think we’re on the cusp of something exhilarating and terrifying.” Subsequent history has resoundingly vindicated him, although perhaps not always in the ways that his inner digital utopianist might have preferred.

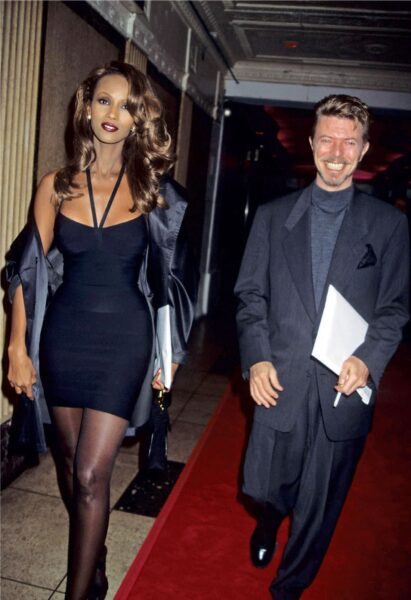

One thing David Bowie was not, however, was a gamer. He took the meeting about Omikron largely at the behest of his son Duncan, who was. He arrived at Eidos’s headquarters accompanied by said son; by his wife, a former supermodel who went by the name of simply Iman; and by his principal musical collaborator of the past decade, the guitarist Reeves Gabrels. They all sat politely but noncommittally while a very nervous group of game developers told them all about Omikron. “Okay, then, what do you need from me?” asked Bowie when the presentation was over. An unusually abashed David Cage said that, at a minimum, they were hoping to license a song or two for the game — maybe the Cold War-era anthem “‘Heroes'” or, failing that, the more recent “Strangers When We Meet.” But in the end, Bowie could be as involved as he wanted to be.

It turned out that he wanted to be quite involved indeed. Over the next couple of hours, Quantic Dream got all they could have dreamed of and then some. Carried away on a wave of enthusiasm, Bowie and Gabrels promised to write and record a whole new album to serve as the soundtrack to the game. And Bowie said he was willing to appear in it personally in motion-captured form. Maybe he and Gabrels could even perform a virtual concert inside the virtual world. Heads were spinning when Bowie and his entourage finally left the building that day.

As promised, Bowie, Iman, and Gabrels came to Paris for a couple of weeks, where they participated in motion-capture and voice-acting sessions and saw and heard more about the world and story of Omikron. Then they went away again; Quantic Dream heard nothing whatsoever from them for months, which made everyone there extremely nervous. But then they popped up again to deliver the finished music — no fewer than ten original songs — right on time, one year almost to the day after they had agreed to the project.

The same tracks were released on September 21, 1999, as hours…, David Bowie’s 23rd studio album. Critics greeted it with some warmth, calling it a welcome return to more conventional songcraft after several albums that had been more electronica than rock. The connection of the music to the not-yet-released game was curiously elided; few reviewers of the album even seemed to realize that it was supposed to be a soundtrack, the first of its type. That same autumn, the veteran progressive-rock group Yes would debut a single original song written for the North American game Homeworld, but Bowie’s contribution to Omikron was on another order of magnitude entirely.

The 1999 David Bowie album hours… was, technically speaking, the soundtrack to Omikron: The Nomad Soul, but you’d have a hard time divining that from looking at it.

Omikron itself appeared about six weeks later. Absolutely no game critic missed the David Bowie connection, which became the lede of every review, thus indicating that the cultural dynamic between games and pop music had perhaps not reached a state of equilibrium just yet. But despite the presence of Bowie, reviews of the game were mixed in Europe, downright harsh in North America. Computer Gaming World got off the best zinger against the game it dubbed Omikrud: “We could be coasters, just for one day.” The magazine went on to explain that “the concept of wrapping an adventure game around a David Bowie album is a cool one. The problem here is with the execution. And your own execution will look more and more desirable, the longer you attempt to play this game.” Rude these words may be, but in my experience they’re the truth.

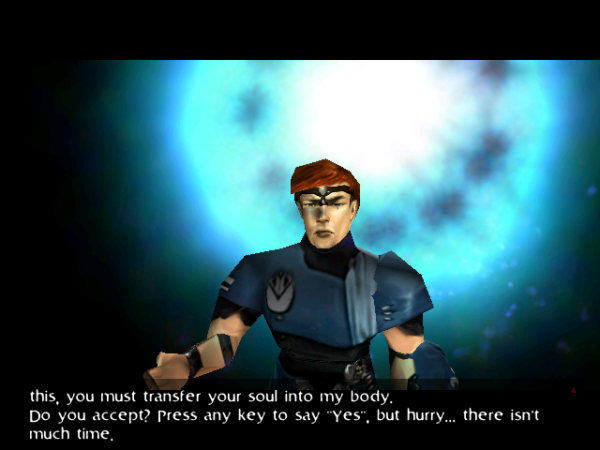

Omikron boasts a striking and memorable opening. When you click the “New Game” button, a fellow dressed in a uniform that looks like a cross between Star Trek and T.J. Hooker pops onto the screen and starts talking directly to you, shattering the fourth wall like so much wet plaster. “My name is Kay’l,” he tells you. (His full name will prove to be Kay’l 669, because of course it is.) “I come from a universe parallel to yours. My world needs your help! You’re the only one who can save us!”

Kay’l wants you to transfer your soul into his body and journey with him back to his home dimension. “You must concentrate!” he hisses. To demonstrate how it’s done, Kay’l holds up his hands and doubles over like a constipated man on a toilet. “You’ve done it!” he then declares with some relief. “Now your soul occupies my body.” (If my soul occupies his body, why am I still sitting in front of my monitor watching him talk at me?) “This is the last time we’ll be able to speak together. Once you’ve crossed the breach, you’ll be on your own. I will take over my body when you leave the game and hold your place until you return.” Thus we learn that Omikron intends to go all-in all the time on diegesis. Lord help us.

You-as-Kay’l emerge in an urban alleyway, only to be set upon by a giant demon that seems as out of place here as you do. This infernal creature is about to make short work of you, thereby revealing a flaw in Kay’l’s master plan. Luckily, a police robot shows up at this juncture and scares away the demon, who apparently isn’t all that after all. “You have been the victim of a violent attack,” RoboCop helpfully informs you, seemingly not noticing that you’re dressed in the uniform of a police officer yourself. “Go home and re-hydrate yourself.”

Trying to take his advice, you fumble about for a while with the idiosyncratic and kind of idiotic controls and interface, and finally manage to locate Kay’l’s apartment. There you discover that he’s married, to a fetching woman whose closet is filled only with hot pants and halter tops. (In time, you will learn that this is true of almost all of the women who live in Omikron.) Seeming unconcerned by the fact that her husband has evidently suffered some sort of psychotic break, disappearing for three days and returning with his memory wiped clean, she lies down on the bed to await your ministrations. You lie down beside her; coitus ensues. Oh, my. Less than half an hour into the game, and you’ve already bonked your poor host’s wife. One wonders whether the fellow is inside his body with you watching the action, so to speak, and, if so, whether he’s beginning to regret fetching you out of the inter-dimensional ether.

Kay’l’s wife will later turn out to be a demon in disguise. I guess that makes it okay to have sex with her under false pretenses. And anyway, these people can do the nasty without having to take their clothes off, just like the characters in a Chris Roberts movie.

I do try to be fair, so let me say now that some things about this game are genuinely impressive. The urban environs qualify at first, especially when you consider that they run in a custom-coded 3D engine. It takes some time for the realization to set in that the city of Omikron is more a carefully curated collection of façades — like a Hollywood soundstage — than a believable community. But once it does, it becomes all too obvious that the people and cars you see aren’t actually going anywhere, even as the overuse of the same models and textures becomes difficult to ignore. There’s exactly one type of car to be seen, for example — and, paying tribute to Henry Ford, it seems to be available in exactly one color. Such infelicities notwithstanding, however, it’s still no mean feat that Quantic Dream pulled off here, a couple of years before Grand Theft Auto III. That you can suspend your disbelief even for a while is an achievement in itself in the context of the times.

Yet this is not a space teeming with interesting interactions and hidden nooks and crannies. With one notable exception, which I’ll get to later, very little that isn’t necessary to the linear main plot is implemented beyond a cursory level. The overarching design is that of a traditional adventure game, not a virtual open world at your beck and call. You learn from Kay’l’s wife — assuming you didn’t figure it out from his uniform — that he is a policeman in this world, on the hunt for a serial killer. (Someone is always a policeman on the hunt for a serial killer in David Cage games.) You have to run down a breadcrumb trail of clues, interviewing suspects and witnesses, collecting evidence, and solving puzzles. The sheer scale of the world is more of a hindrance than a benefit to this type of design, because of the sheer quantity of irrelevancies it throws in your face. By the time you get into the middle stages of the game, it’s becoming really, really hard to figure out where it wants you to go next amidst this generic urban sprawl. And by the same point, your little law-enforcement exercise has become a hunt for demons who are on the verge of destroying the entire multiverse, as you crash headlong into a bout of plot inflation that would shock a denizen of the Weimar Republic. The insane twists and turns the plot leads you through do nothing to help you figure out what the hell the game wants from you.

But I was trying to be kind, wasn’t I? In that spirit, let me note that there are forward-thinking aspects to the design. One of David Cage’s overriding concerns throughout his career has been the elimination of game-over failure states. If you get yourself killed here, the game will always find some excuse to bring you back to life. Unfortunately, the plot engine is littered with soft locks, whereby you can make forward progress impossible by doing or not doing something at the right or wrong moment. I assume that these were inadvertent, but that doesn’t make them any more excusable. This is one of several places where the game breaks an implicit contract it has made with its player. It strongly implies at the outset that you can wing it, that you’re expected to truly inhabit the role of a random Joe Earthling whose (nomad) soul has been sucked into this alternative dimension. But in actuality you have to meta-game like crazy to have a chance.

The save system is a horror, a demonstration of all the ways that the diegetic approach can go wrong. You have to find save points in the world, then use one of a limited supply of “magic rings” you find lying around to access them. In addition to being an affront to busy adults who might not be able to play for an extra half-hour looking for the next save point — precisely the folks whom David Cage says games need to become better at attracting — this system is another great way to soft-lock yourself; use up your supply of magic rings and you’re screwed if you can’t find some more. There is a hint system of sorts built into the game, but it’s accessible only at the save points, and requires you to spend more magic rings to use it. In other words, the player who most needs a hint will be the least likely to have the resources to hand by which to get one. This is another running theme of Omikron: ideas that are progressive and player-friendly in an abstract sense, only to be implemented in a bizarrely regressive, player-hostile way. It bears all the telltale signs of a game that no one ever really tried to play before it was foisted on an unsuspecting public.

And then there are the places where Omikron suddenly decides to cease being an adventure game and become a beat-em-up, a first-person shooter, or a platformer. I hardly know how to describe just how jarring these transitions are, coming out of the blue with no warning whatsoever. You’ll be in a bar, chatting up the patrons for clues — and bam, you’re in shooter mode. You’ll be searching a locker room — and suddenly you’re playing Mortal Kombat against a dude in tighty-whities. These action modes play as if someone once told the people who made this game about Mortal Kombat and Quake and Tomb Raider, but said people have never actually experienced any of those genres for themselves.

I struggled mightily with the beat-em-up mode at first because I kept trying to play it like a real game of this type — watching my opponent, varying my attacks, trying to establish some sort of rhythm. Then a friend explained to me that you can win every fight just by picking one attack and pounding on that key like a hyperactive monkey, finesse and variety and rhythm be damned.

Alas, the FPS mode is a tougher nut to crack. The default controls are terrible, having nothing in common with any other shooter ever, but you can at least remap them. Sadly, the other problems have no similarly quick fix. Enemies can shoot you when they’re too far away for you to even see them; enemies can spawn out of nowhere right on top of you; your own movements are weirdly jerky, such that it’s hard to aim properly even in the best of circumstances. Just how ineptly is the FPS mode of Omikron implemented, you ask? So ineptly that you can’t even access your health packs during a fight. Again, it’s hard to believe that oversights like this one would have persisted if the developers had ever bothered to ask anyone at all to play their game before they stuck it in a box and shipped it.

The jumping sequences at least take place in the same interface paradigm as the adventure game, but the controls here are just as sloppy, enough to make Omikron the most infuriating platformer since Ultima VIII tarnished a proud legacy. And don’t even get me started on the swimming — your character is inexplicably buoyant, meaning you’re constantly battling to keep his head underwater rather than the opposite — or the excruciating number of times you’ll see the words “I don’t know what to do with that” flash across the screen because you aren’t standing just right in front of the elevator controls or the refrigerator or the vending machine. Even David Cage, a man not overly known for his modesty, confesses that “I wanted to mix different genres, but I wouldn’t say that we were 100-percent successful.” (What percentage successful would you say that you were, David?)

Then we have the writing, the one area where we might have expected Omikron to excel, based on the rhetoric surrounding it. It does not. The core premise, an invasion by demons of a city lifted straight out of Blade Runner, smacks more of adolescent fan fiction than the adult concerns David Cage yearns for games to learn to address. As I already noted, the plot grows steadily more incoherent as it unspools. Interesting, even disturbing elements do churn to the surface with reasonable frequency, but the script is bizarrely oblivious to them. As the game goes on, for instance, you acquire the ability to jump into other bodies than that of poor cuckolded Kay’l. Sometimes you have to sacrifice these bodies — murdering them from the point of view of the souls that call them home — in order to continue the story. The game never acknowledges that this is morally problematic, never so much as feints toward the notion of a greater good or ends justifying the means. This refusal of the game to address the deeper ramifications of its own fiction contributes as much as the half-realized city to giving the whole experience a shallow, plastic feel. Omikron brings up a lot of ideas, but seemingly only because David Cage thinks they sound cool; it has nothing to really say about anything.

Mind you, not having much of anything to say is by no means the kiss of death for a game; I’ve played and loved plenty of games with nothing in particular on their minds. But those games were, you know, fun in other ways. There’s very little fun to be had in Omikron. Everything is dismayingly literal; there isn’t a trace of humor or whimsy or poetry anywhere in the script. I found it to be one of the most oppressive virtual spaces I’ve ever had the misfortune to inhabit.

Among the many insufferable quotes attached to Omikron is the claim by Phil Campbell, a senior designer at Eidos who went on to become creative director at Quantic Dream, that the soul-transfer mechanic makes it “the world’s first Buddhist game.” A true believer who has drunk all the Kool Aid, Campbell thinks Cage is an auteur on par with François Truffaut.

Even the most-discussed aspect of Omikron, at the time of its release and ever since, winds up more confusing than effective. David Cage admits to being surprised by the songs that David Bowie turned up with a year after their first meeting. On the whole, they were sturdy songs if not great ones, unusually revealing and unaffected creations from a man who had made a career of trying on different personas. “I wanted to capture a kind of universal angst felt by many people of my age,” said the 52-year-old singer. The lyrics were full of thoughtful and sometimes disarmingly wise ruminations about growing older and learning to accept one’s place in the world, set in front of the most organic, least computerized backing tracks that Bowie had employed in quite some years. But the songs had little or nothing to do with Cage’s game, in either their lyrics or their sound. Cage claims that Bowie taught him a valuable lesson with his soundtrack: “It’s important that the music doesn’t say the same thing that the imagery does.” A more cynical but possibly more accurate explanation for the discrepancy is that Bowie pretty much forgot about the game and simply made the album he felt like making.

The one place where Omikron’s allegedly open world does reward exploration is the underground concerts you can discover and attend, by a band called the Dreamers who have as their lead singer a de-aged David Bowie. The virtual rock star’s name is a callback to the real star’s distant past: David Jones, the name Bowie was born with. He flounces around the stage like Ziggy Stardust in his prime, dressed in an outfit whose most prominent accessory is a giant furry codpiece. But the actual songs he sings are melancholy meditations on age and time, clearly not the output of a twenty-something glam-rocker. It’s just one more place where Omikron jarringly fails to come together to make a coherent whole, one more way in which it manages to be less than the sum of its parts.

That giant codpiece on young Mr. Jones brings me to one last complaint: this game is positively drenched in cheap, exploitive sex that’s more tacky than titillating. It’s this that turned my dislike for it to downright distaste. Strip clubs and peep shows and advertisements for “biochemical penis implants” abound. Of course, all those absurdly proportioned bodies and pixelated boobies threatening to take your eyes out look ridiculous rather than sexy, as they always do in 3D games from this era. At one point, you have to take over a woman’s body — a body modeled on that of David Bowie’s wife Iman, just to make it extra squicky — and promise sexual favors to a shopkeeper in order to advance the plot. At least you aren’t forced to follow through; thank God for small blessings.

The abject horniness makes Omikron feel more akin to that other kind of entertainment that’s labeled as “adult” — you know, the kind that’s most voraciously consumed by people who aren’t quite adults yet — than it does to the highbrow films to which David Cage has so frequently paid lip service. I won’t accuse Cage of being a skeezy creep; after all, it’s not as if I know the guy. I will only say that, if a skeezy creep was to make a game, I could easily imagine it turning out something like this.

Omikron’s world is the definition of wide rather than deep, but the developers were careful to ensure that you can pee into every single toilet you come across. Make of that what you will.

Once ported to the Sega Dreamcast console in addition to Windows computers, Omikron sold about 400,000 copies in all in Europe, but no more than 50,000 in North America. “It was too arty, too French, too ‘something’ for the American market,” claims David Cage. (I can certainly think of some adjectives to insert there…) Even its European numbers were not good enough to get the direct sequel that Cage initially proposed funded, but were enough, once combined with his undeniable talent for self-marketing, to allow him to continue his career as a would-be gaming auteur. So, we’ll be meeting him again, but not for a few years. We’ll just have to hope that he’s improved his craft by that point.

When I think back on Omikron, I find myself thinking about another French — or rather Francophone Belgian — game as a point of comparison. On the surface, Outcast, which was released the very same year as Omikron, possesses many of the same traits, being another genre-mixing open-world narrative-driven game with a diegetic emphasis that extends as far as the save system; even the name is vaguely similar. I tried it out some months ago at the request of a reader, going into it full of hard-earned skepticism toward what used to be called the “French Touch,” that combination of arty themes and aesthetics with, shall we say, less focus on the details of gameplay. Much to my own shock, I ended up kind of loving it. For the developers of Outcast did sweat those details, did everything they could to make sure their players had a good time instead of just indulging their own masturbatory fantasies about what a game could be. It turns out that some French games are generous, just like some of them from other cultures; others are full of themselves like Omikron.

To be sure, there are people who love this game too, even some who call it their favorite game ever, a cherished piece of semi-outsider interactive art. Far be it from me to tell these people not to feel as they do. Personally, though, I’ve learned to hate this pile of pretentious twaddle with a visceral passion. It’s been years since I’ve seen a game that fails so thoroughly at every single thing it tries to do. For that, Omikron deserves to be nominated as the Worst Game of 1999.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The books The Complete David Bowie by Nicholas Pegg, Starman: David Bowie, The Definitive Biography by Paul Trynka, and Bowie: The Illustrated Story by Pat Gilbert. The manual for David Cage’s later game Fahrenheit; PC Zone of November 1999; Computer Gaming World of March 2000; Retro Gamer 153.

Online sources include “David Cage: From the Brink” at MCV, “The Making of Omikron: The Nomad Soul“ at Edge Online, “Omikron Team Interviewed” at GameSpot, “How David Bowie’s Love for the Internet Led Him to Star in a Terrible Dreamcast Game” by Brian Feldman for New York Magazine, “Quantic Dream at 25: David Cage on David Bowie, Controversies, and the Elevation of Story” by Simon Parkin for Games Radar, “The Amazing Stories of a Man You’ve Never Heard of” by Robert Purchese for EuroGamer, “David Cage : « L’attitude de David Bowie m’a profondément marqué »” by William Audureau for Le Monde, “David Bowie’s 1999 Gaming Adventure and Virtual Album” by Richard MacManus for Cybercultural, “Fahrenheit : Interview David Cage / part 1 : L’homme orchestre” by Francois Bliss de la Boissiere for OverGame.com, “Quantic Dream’s David Cage Talks about His Games, His Career, and the PS4: It Allows to ‘Go Even Further'” by Giuseppe Nelva for DualShockers, Quantic Dream’s own version of its history on the studio’s website, and a 2000 David Bowie interview with the BBC’s Jeremy Paxman.

Where to Get It: Omikron: The Nomad Soul is available as a digital purchase at GOG.com.