The name of Bill Budge has already come up from time to time on this blog. Mentioning him has been almost unavoidable, for he was one of the titans amongst early Apple II programmers, worshiped for his graphical wizardry by virtually everyone who played games. As you may remember, his name carried such weight that when Richard Garriott was first contacted by Al Remmers of California Pacific to propose that he allow CP to publish Akalabeth Garriott’s first reaction was a sort of “I’m not worthy” sense of shock at the prospect of sharing a publisher with the great Budge. Having arrived at the time of the birth of Electronic Arts and Budge’s masterpiece, Pinball Construction Set, now seems a good moment to take a step back and look at what made Budge such a star.

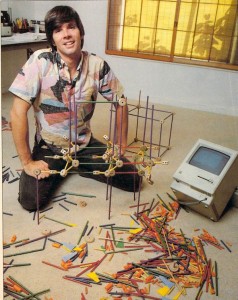

Budge was always a tinkerer, always fascinated by the idea of construction sets. As a young kid, he played with blocks, tinker toys, erector sets. As an older kid, he moved on to fiddling with telescopes and model rockets. (“It’s amazing we didn’t kill ourselves.”) After moving about the country constantly when Budge was younger, his family finally ended up in the San Francisco Bay area by the time Budge began high school in the late 1960s. It was a fortuitous move. With the heart of the burgeoning Silicon Valley easily accessible, Budge’s family had found the perfect spot for a boy who liked to tinker with technology. A teacher at his school named Harriet Hungate started a class in “computer math” soon after Budge arrived. The students wrote their programs out by hand, then sent them off to a local company that had agreed to donate some time on their IBM 1401 minicomputer. They then got to learn whether their programs had worked from a printout sent back to the school. It was a primitive way of working, but Budge was immediately smitten. He calls the moment he discovered what a loop is one of the “transcendent moments” in his life. He “just programmed all the time” during his last two years of high school. Hungate was eventually able to finagle a deal with another local business to get a terminal installed at the school with a connection to an HP 2100 machine hosting HP Time-Shared BASIC. Budge spent hours writing computer versions of Tic-tac-toe, checkers, and Go.

But then high school was over. Without the ready access to computers that his high school had afforded him, Budge tried to put his programming behind him. He entered the University of California Santa Cruz as an English major, with vague aspirations toward becoming a novelist. Yet in the end the pull of programming proved too strong. After two years he transferred to Berkeley as a computer-science major. He got his Bachelor’s there, then stayed on to study for a PhD. He was still working on that in late 1978 when the Apple II first entered his life.

As you might expect, the arrival of the trinity of 1977 had prompted considerable discussion within Berkeley’s computer-science department. Budge dithered for a time about whether to buy one, and if so which one. At last friend and fellow graduate student Andy Hertzfeld convinced him to go with the local product of nearby Apple Computer. It wasn’t an easy decision to make; the Commodore PET and the TRS-80 were both much cheaper (a major consideration for a starving student), and the TRS-80 had a vastly larger installed base of users and much more software available. Still, Budge decided that the Apple II was worth the extra money when he saw the Disk II system and the feature that would make his career, the bitmapped hi-res graphics mode. He spent half of his annual income on an Apple II of his own. It was so precious that he would carefully stow the machine away back in its box, securely swaddled in its original protective plastic, whenever he finished using it.

As he explored the possibilities of his treasure, Budge kept coming back again and again to hi-res mode. He worked to divine everything about how it worked and what he might do with it. His first big programming project became to rewrite much of Steve Wozniak’s original game of Breakout which shipped with every early Apple II. He replaced Woz’s graphics code with his own routines to make the game play faster and smoother, more like its arcade inspiration. When he had taken that as far as he could, he started thinking about writing a game of his own. He was well-acquainted with Pong from a machine installed at the local pizza parlor. Now he recreated the experience on the Apple II. He names “getting my first Pong ball bouncing around on the screen” as another of his life’s transcendent moments: “When I finished my version of Pong, it was kind of a magical moment for me. It was night, and I turned the lights off in my apartment and watched the trailing of the ball on the phosphors of my eighty-dollar black and white TV.” He added a number of optional obstacle layouts to the basic template for variety, then submitted the game, which he named Penny Arcade, to Apple themselves. They agreed to trade him a printer for it, and earmarked it for The Apple Tapes, a cassette full of “introductory programs” to be included with every specimen of the new Apple II Plus model they were about to release. In the manual for the collection they misattributed the game to “Bob Budge,” but it mattered little. Soon enough everyone would know his name.

With his very first game shipping with every Apple II Plus, Budge was naturally happy to continue with his new hobby. He started hanging around the local arcades, observing and taking careful notes on the latest games. Then he would go home and clone them. Budge had little interest in playing the games, and even less in playing the role of game designer. For him, the thrill — the real game, if you will — was in finding ways to make his little Apple II produce the same visuals and gameplay as the arcade machines, or at least as close as he could possibly get. In a few years Atari would be suing people for doing what Budge was doing, but right now the software industry was small and obscure enough that he could get away with it.

Budge’s big breakthrough came when a friend of his introduced him to a traveling sales rep named Al Remmers, who went from store to store selling 8″ floppy disk drives. He and Budge made a deal: Remmers would package the games up in Ziploc baggies and sell them to the stores he visited on his treks, and they would split the profits fifty-fifty. Budge was shocked to earn $7000 for the first month, more than his previous annual income. From this relationship was born Remmers’s brief-lived but significant software-publishing company, California Pacific, as well as Budge’s reputation as the dean of Apple II graphics programmers. His games may not have been original, but they looked and played better than just about anything else out there. To help others who dreamed of doing what he did, he packaged some of his routines together as Bill Budge’s 3-D Graphics System. His reputation was such that this package sold almost as well as his games. This was how easily fame and fortune could come to a really hot programmer for a brief window of a few years, when word traveled quickly in a small community aching for more and better software for their machines.

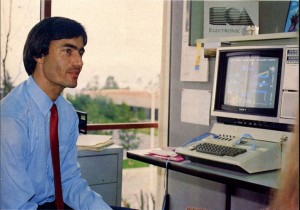

In fact, his reputation soared so quickly that Apple themselves came calling. Budge, who had been putting less and less effort into his studies as his income from his games increased, dropped out of Berkeley to join his old buddy Andy Hertzfeld in Cupertino. He was made — what else? — a graphics specialist working in the ill-fated Apple III division. He ended up spending only about a year at Apple during 1980 and 1981, but two experiences there would have a huge impact on his future work, and by extension on the field of computer gaming.

While Budge was working at Apple much of the engineering team, including Hertzfeld and even Woz himself, were going through a hardcore pinball phase: “They were students of the game, talking about catches, and how to pass the ball from flipper to flipper, and they really got into it.” Flush with cash as they were after the IPO, many at Apple started filling their houses with pinball tables.

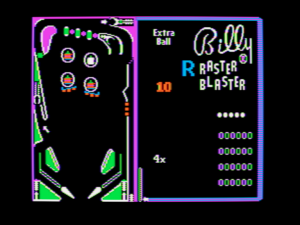

Budge didn’t find pinball intrinsically all that much more interesting than he did purely electronic arcade games. Still, one of the first games Budge sold through Remmers had been a simple pinball game, which was later included in his very successful Trilogy of Games package published by California Pacific. Pinball was after all a fairly natural expansion of the simple Pong variants he started with. Now, witnessing the engineers’ enthusiasm led him to consider whether he could do the game better justice, create something on the Apple II that played and felt like real pinball, with the realistic physics that are so key to the game. It was a daunting proposition in some ways, but unusually susceptible to computer simulation in others. A game of pinball is all about physics, with no need to implement an opponent AI. And the action is all centered around that single moving ball while everything else remains relatively static, meaning it should be possible to do on the Apple II despite that machine’s lack of hardware sprites. (This lack made the Apple II less suited for many action games than the likes of the Atari 8-bit computers or even the Atari VCS.) After some months of work at home and after hours, Budge had finished Raster Blaster.

Raster Blaster was the best thing Budge had yet done — so good that he decided he didn’t want to give it to California Pacific. Budge felt that Remmers wasn’t really doing much for him by this point, just shoveling disks into his homemade-looking packaging, shipping them off to the distributor SoftSel, and collecting 50% of the money that came back. The games practically sold themselves on the basis of Budge’s name, not California Pacific’s. Budge was a deeply conflict-averse personality, but his father pushed him to cut his ties with California Pacific, to go out on his own and thereby double his potential earnings. And anyway, he was getting bored in his job at Apple. So he quit, and along with his sister formed BudgeCo. He would write the games, just as he always had, and she would handle the business side of things. Raster Blaster got BudgeCo off the ground in fine form. It garnered rave reviews, and became a huge hit in the rapidly growing Apple II community, Budge’s biggest game yet by far. Small wonder — it was the first computer pinball game that actually felt like pinball, and also one of the most graphically impressive games yet seen on the Apple II.

But next came the question of what to do for a follow-up. It was now 1982, and it was no longer legally advisable to blatantly clone established arcade games. Budge struggled for weeks to come up with an idea for an original game, but he got nowhere. Not only did he have no innate talent for game design, he had no real interest in it either. Out of this frustration came the brilliant conceptual leap that would make his legacy.

Above I mentioned that two aspects of Budge’s brief time at Apple would be important. The other was the Lisa project. Budge did not directly work on or with the Lisa team, but he was fascinated by their work, and observed their progress closely. Like any good computer-science graduate student, he had been aware of the work going on at Xerox PARC. Yet he had known the Alto’s interface only as a set of ideas and presentations. When he could actually play with a real GUI on the Lisa prototypes, it made a strong impression. Now it provided a way out of his creative dilemma. He was disinterested in games and game design; what interested him was the technology used to make games. Therefore, why not give people who actually did want to become designers a set of tools to let them do that? Since these people might be no more interested in programming than he was in design, he would not just give them a library of code like the old 3-D Graphics System he had published through California Pacific. No, he would give them a visual design tool to make their own pinball tables, with a GUI interface inspired by the work of the Lisa team.

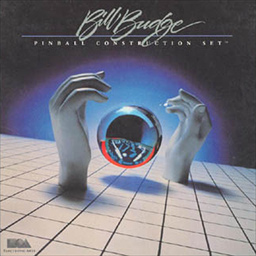

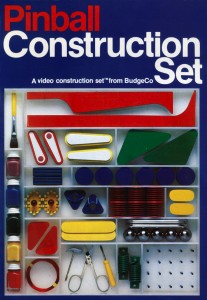

The original Pinball Construction Set box art, featuring pieces of the pinball machine that Budge disassembled to plan the program

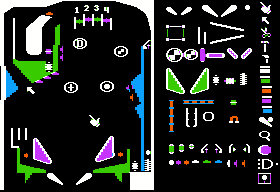

Budge had resisted buying a pinball table of his own while at Apple, but now he bought a used model from a local thrift shop. He took it apart carefully, cataloging the pieces that made up the playfield. Just as the Lisa’s interface used a desktop as its metaphor, his program would let the user build a pinball machine from a bin of iconographic spare parts. The project was hugely more ambitious than anything he had tackled before, even if some of the components, such as a simple paint program that let the user customize the look of her table, he had already written for his personal use in developing Raster Blaster. Budge was determined to give his would-be creator as much scope as he possibly could. That meant fifteen different components that she could drag and drop anywhere on the surface of her table. It meant letting her alter gravity or the other laws of physics if she liked. It meant letting her make custom scoring combinations, so that bumping this followed by that gave double points. And, because every creator wants to share her work, it meant letting the user save her custom table as a separate program that her friends could load and play just like they did Budge’s own Raster Blaster. That Budge accomplished all of this, and in just 48 K of memory, makes Pinball Construction Set one of the great feats of Apple II programming. None other than Steve Wozniak has called it “the greatest program ever written for an 8-bit machine.”

Amazing as it was, when BudgeCo released Pinball Construction Set at the end of 1982 its sales were disappointing. It garnered nowhere near the attention of Raster Blaster. The software industry had changed dramatically over the previous year. A tiny operation like BudgeCo could no longer just put a game out — even a great, groundbreaking game like PCS — and wait for sales. It was getting more expensive to advertise, harder to get reviews and get noticed in general. Yet when Trip Hawkins came to him a few months later asking to re-release PCS through his new publisher Electronic Arts, Budge was reluctant, nervous of the slick young Hawkins and his slick young company. But Hawkins just wouldn’t take no for an answer; he said he would make Budge and his program stars, said that only he could find PCS the audience its brilliance deserved — and he offered one hell of a nice advance and royalty rate to boot. And EA did have Woz himself on the board of directors, and Woz said he thought signing up would be a smart move. Budge agreed at last; thus BudgeCo passed into history less than two years after its formation.

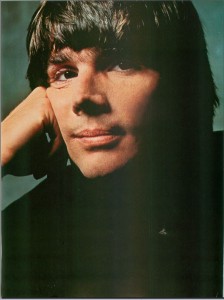

As good as PCS was, it’s very possible that Hawkins had another, ulterior motive in pursuing Budge with such vigor. To understand how that might have been, we need to understand something about what Budge was like personally. Given the resume I’ve been outlining — spent his best years of high school poring over computer code; regarded his Apple II as his most precious possession; had his most transcendent moments programming it; etc. — you’ve probably already formulated a shorthand picture. If the Budge of that picture is, shall we say, a little bit on the nerdy, introverted side, you can be forgiven. The thing was, however, the real Budge was nothing like what you might expect; as he himself put it, he “didn’t quite fit the mold.” He had a tall, rangy build and handsome features beneath a luxurious head of hair, with striking eyes that a teenage girl might call dreamy. At 29 (although he looked perhaps 22), he was comfortable in his own skin in a way that some people never manage, with an easy grace about him that made others as glad to talk to him as they were to listen. His overall persona smacked more of enlightened California beach bum than hardcore programmer. And he took a great picture. If there was one person amongst Hawkins’s initial crew of developers who could actually pull off the rock star/software artist role, it was Budge; he might even attract a groupie or two. He was a dream come true for the PR firm Hawkins had inherited from his time at Apple, Regis McKenna, Inc. Thus the EA version of PCS was designed to look even more like a contemporary rock album than any of the other games. The name of Bill Budge, the man EA planned to make their very own rock star, was far larger on it than the name of his game.

The down-to-earth Budge himself was rather bemused by EA’s approach, but he shrugged his shoulders and went along with it in his usual easygoing manner. When EA arranged for rock photographer Norman Seeff to do the famous “software artists” photo shoot, they asked that the subjects all wear appropriately bohemian dark clothing to the set. Budge went one better: he showed up with a single studded leather glove he’d bought for dressing up as a punk rocker for a party thrown by the Apple Macintosh team. He brought it simply as a joke, a bit of fun poked at all this rock-star noise. Imagine, then, how shocked he was when Seeff and the others demanded that he actually wear it. Thus Budge in his leather glove became the standout figure from that iconic image. As he later sheepishly admitted, “That’s not really me.” Soon after he got a software-artist photo shoot and advertisement all to himself, filled with vague profundities that may or may not have actually passed his lips beforehand. (“Programming for a microcomputer is like writing a poem using a 600-word vocabulary.”)

EA booked Budge into every gig they could find for him. He did a lengthy one-on-one interview with Charlie Rose for CBS News Nightwatch (“He knew absolutely nothing. He seemed like your typical blow-dried guy without a lot of substance. But I guess I was wrong about him.”); he demonstrated PCS alongside Hawkins on the influential show Computer Chronicles; he featured in a big segment on Japanese television, at a time when that country’s own designers were toiling in obscurity for their parent corporations; he had his photo on the cover of The Wall Street Journal; he was featured alongside the likes of Steve Jobs in an Esquire article on visionaries under the age of forty.

With his album out and the photo shoots done and the promotional spots lined up, it still remained for EA’s rock star to hit the road — to tour. If the highs just described were pretty intoxicating for a computer-game programmer, this part of the process kept him most assuredly grounded. Budge and EA’s Bing Gordon went on a series of what were billed as “Software Artists Tours,” sometimes accompanied by other designers, sometimes alone. The idea was something like a book tour, a chance to sign autographs and meet the adoring fans. Determined to break beyond the ghetto of traditional computer culture, EA booked them not only into computer stores but also into places like Macy’s in New York City, where they were greeted with confusion and bemusement. Even the computer stores sometimes seemed surprised to see them. Whether because of communications problems or flat disinterest, actual fans were often rare or nonexistent at the events. Hawkins’s dream of hordes of fans clutching their EA albums, fighting for an autograph… well, it didn’t happen, even though PCS became a major hit in its new EA duds (it would eventually sell over 300,000 copies across all platforms, a huge figure in those days). Often there seemed to be more press people eager to score an interview than actual fans at the appearances, and often the stores themselves didn’t quite know what to do with their software artists. One manager first demanded that Budge buy himself a new outfit (he was under-dressed in the manager’s opinion to be “working” in his store), then asked him if he could make himself useful by going behind the register and ringing up some customers. “That’s when I realized maybe I wouldn’t be a rock star,” a laconic Budge later said.

Budge wasn’t idle in the down-times between PR junkets. Privileged with one of the few Macintosh prototypes allowed outside of Apple, he used its bundled MacPaint application as the model for MousePaint, a paint program that Apple bundled with the first mouse for the Apple II. He also ported PCS to the Mac. Still, the fans and press were expecting something big, something as revolutionary as PCS itself had been — and small wonder, given the way that EA had hyped him as a visionary.

One of the most gratifying aspects of PCS had been the unexpected things people found to do with it, things that often had little obvious relationship to the game of pinball. Children loved to fill the entire space with bumpers, then watch the ball bouncing about among them like a piece of multimedia art. Others liked to just use the program’s painting subsections to make pictures, scattering the ostensible pinball components here and there not for their practical functions but for aesthetic purposes. If people could make such creative use of a pinball kit, what might they do with something more generalized? As uninterested as ever in designing a game in the traditional sense, Budge began to think about how he could take the concept of the construction set to the next step. He imagined a Construction Set Construction Set, a completely visual programming environment that would let the user build anything she liked — something like ThingLab, an older and admittedly somewhat obtuse stab at the idea that existed at Xerox PARC. His ideas about Construction Set Construction Set were, to say the least, ambitious:

“I could build anything from Pac-Man to Missile Command to a very, very powerful programming language. It’s the kind of a program that has a very wide application. A physics teacher, for example, could build all kinds of simulations, of little micro-worlds, set up different labs and provide dynamic little worlds that aren’t really videogames.”

It turned out to be a bridge too far. Budge tinkered with the idea for a couple of years, but never could figure out how to begin to really implement it. (Nor has anyone else in the years since.) In fact, he never made a proper follow-up to PCS at all. Ironically, Budge, EA’s software artist who best looked the part, was one of the least able to play the role in the long term. As becomes clear upon reading any interview with Budge, old or new, his passion is not for games; it’s for code. In the early days of computer gaming the very different disciplines of programming and game design had been conflated into one due to the fact that most of the people who owned computers and were interested in making games for them were programmers. During the mid-1980s, however, the two roles began to pull apart as the people who used computers and the way games were developed changed. Budge fell smack into the chasm that opened up in the middle. Lauded as a brilliant designer, he was in reality a brilliant programmer. People expected from him something he didn’t quite know how to give them, although he tried mightily with his Construction Set Construction Set idea.

So, he finally just gave up. After 1984 the interviews and appearances and celebrity petered out. His continuing royalties from PCS made work unnecessary for some years, so he all but gave up programming, spending most of his time wind-surfing instead (a sport that Bing Gordon, perhaps to his regret, had taught him). Most people would have a problem going back to obscurity after being on television and newspaper features and even having their own magazine column (in Softalk), but it seemed to affect Budge not at all: “I’m kind of glad when I don’t have anything new out and people forget about me.” Eventually EA quietly accepted that they weren’t going to get another game from him and quit calling. Budge refers to this period as his “years in the wilderness.” By 1990 the name of Bill Budge, such a superstar in his day, came up only when the old-timers started asking each other, “Whatever happened to….?”

In the early 1990s, Budge, now married and more settled, decided to return to the games industry, first to work on yet another pinball game, Virtual Pinball for the Sega Genesis console. Without the pressure of star billing to live up to and with a more mature industry to work in that had a place for his talents as a pure programmer’s programmer, he decided to continue his career at last. He’s remained in the industry ever since, unknown to the public but respected immensely by his peers within the companies for which he’s worked. For Budge, one of those people who has a sort of innate genius for taking life as it comes, that seems more than enough. Appropriately enough, he’s spent most of his revived careers as what’s known as a tools programmer, making utilities that others then use to make actual games. In that sense his career, bizarre as its trajectory has been, does have a certain consistency.

PCS, his one towering achievement as a software artist, deserves to be remembered for at least a couple of reasons. First of all there is of course its status as the first really elegant tool to let anyone make a game she could be proud of. It spawned a whole swathe of other “construction set” software, from EA and others, all aimed at fostering this most creative sort of play. That’s a beautiful legacy to have. Yet its historical importance is greater than even that would imply. PCS represents to my knowledge the first application of the ideas that began at Xerox PARC to an ordinary piece of software which ordinary people could buy at an ordinary price and run on ordinary computers. It proved that you didn’t need an expensive workstation-class machine like the Apple Lisa to make friendlier, more intuitive software; you could do it on a 48 K Apple II. No mouse available? Don’t let that stop you; use a joystick or a set of paddles or just the arrow keys. Thousands and thousands of people first saw a GUI interface in the form of Pinball Construction Set. Just as significantly, thousands of other designers saw its elegance and started implementing similar interfaces in their own games. The floating, disembodied hand of PCS, so odd when the game first appeared, would be seen everywhere in games within a couple of years of its release. And game manuals soon wouldn’t need to carefully define “icon,” as the PCS manual did. PCS is a surprising legacy for the Lisa project to have; certainly the likes of it weren’t anything anyone involved with Lisa was expecting or aiming for. But sometimes legacies are like that.

Next time we’ll look at another of those seminal early EA games. If you’d like to try to make something of your own in the meantime, here’s the Apple II disk image and manual for Pinball Construction Set.

(What with his celebrity in Apple II circles between 1979 and 1985, there’s a lot of good information on Budge available in primary-source documents from the period. In particular, see the November 1982 Softline, the December 1985 Compute!’s Gazette, the March 1985 Electronic Games, the March 1985 Enter, the September 1984 Creative Computing, and Budge’s own column in later issues of Softalk. Budge is also featured in Halcyon Days, and Wired magazine published a retrospective on his career when he was given a Pioneer Award by the Academy of Interactive Arts and Sciences in 2011. Budge’s interview at the awards ceremony was videotaped and is available for viewing online.)