Is it the actor or the drama

Playing to the gallery?

Or is it but the character

Of any single member of the audience

That forms the plot

of each and every play?

I was introduced to the contrast between art as artifact and art as experience by an episode of Northern Exposure, a television show which meant a great deal to my younger self. In “Burning Down the House,” Chris in the Morning, the town of Cicely, Alaska’s deejay, has decided to fling a living cow through the air using a trebuchet. Why? To create a “pure moment.”

“I didn’t know what you are doing was art,” says Shelley, the town’s good-hearted bimbo. “I thought it had to be in a frame, or like Jesus and Mary and the saints in church.”

“You know, Shell,” answers Chris in his insufferable hipster way, “the human soul chooses to express itself in a profound profusion of ways, not just the plastic arts.”

“Plastic hearts?”

“Arts! Plastic arts! Like sculpture, painting, charcoal. Then there’s music and poetry and dance. Lots of people, Susan Sontag notwithstanding, include photography.”

“Slam dancing?”

“Insofar as it reflects the slam dancer’s inner conflict with society through the beat… yeah, sure, why not? You see, Shelley, what I’m dealing with is the aesthetics of the transitory. I’m creating tomorrow’s memories, and, as memories, my images are as immortal as art which is concrete.”

Certain established art forms — those we generally refer to as the performing arts — have this quality baked into them in an obvious way. Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones once made the seemingly arrogant pronouncement that his band was “the greatest rock-and-roll band in the world” — but later modified his statement by noting that “on any given night, it’s a different band that’s the greatest rock-and-roll band in the world.” It might be the Rolling Stones playing before an arena full of 20,000 fans one night, and a few sweaty teenagers playing for a cellar full of twelve the next. It has nothing to do with the technical skill of the musicians; music is not a skills competition. A band rather becomes the greatest rock-and-roll band in the world the moment when the music goes someplace that transcends notes and measures. This is what the ancient Greeks called the kairos moment: the moment when past and future and thought itself fall away and there are just the band, the audience, and the music.

But what of what Chris in the Morning calls the “plastic arts,” those oriented toward producing some physical (or at least digital) artifact that will remain in the world long after the artist has died? At first glance, the kairos moment might seem to have little relevance here. Look again, though. Art must always be an experience, in the sense that there is a viewer, a reader, or a player who must experience it. And the meaning it takes on for that person — or lack thereof — will always be profoundly colored by where she was, who she was, when she was at the time. You can, in other words, find your own transitory transcendence inside the pages of a book just as easily as you can in a concert hall.

The problem with the plastic arts is that it’s too easy to destroy the fragile beauty of that initial impression. It’s too easy to return to the text trying to recapture the transcendent moment, too easy to analyze it and obsess over it and thereby to trample it into oblivion.

But what if we could jettison the plastic permanence from one of the plastic arts, creating something that must live or die — like a rock band in full flight or Chris in the Morning’s flying cow — only as a transitory transcendence? What if we could write a poem which the reader couldn’t return to and fuss over and pin down like a butterfly in a display case? What if we could write a poem that the reader could literally only read one time, that would flow over her once and leave behind… what? As it happens, an unlikely trio of collaborators tried to do just that in 1992.

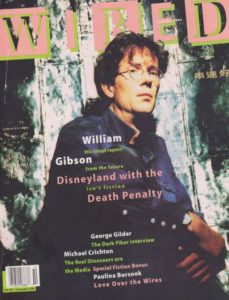

Very early that year, a rather strange project prospectus made the rounds of the publishing world. Its source was Kevin Begos, Jr., who was known, to whatever extent he was known at all, as a publisher of limited-edition art books for the New York City gallery set. This new project, however, was something else entirely, and not just because it involved the bestselling science-fiction author William Gibson, who was already ascending to a position in the mainstream literary pantheon as “the prophet of cyberspace.”

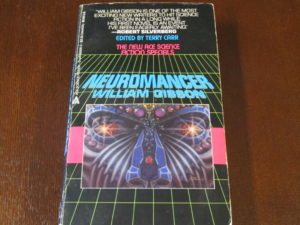

Kevin Begos Jr., publisher of museum-quality, limited edition books, has brought together artist Dennis Ashbaugh (known for his large paintings of computer viruses and his DNA “portraits”) and writer William Gibson (who coined the term cyberspace, then explored the concept in his award-winning books Neuromancer, Count Zero, and Mona Lisa Overdrive) to produce a collaborative Artist’s Book.

In an age of artificial intelligence, recombinant genetics, and radical, technologically-driven cultural change, this “Book” will be as much a challenge as a possession, as much an enigma as a “story”.

The Text, encrypted on a computer disc along with a Virus Program written especially for the project, will mutate and destroy itself in the course of a single “reading”. The Collector/Reader may either choose to access the Text, thus setting in motion a process in which the Text becomes merely a Memory, or preserve the Text unread, in its “pure” state — an artifact existing exclusively in cyberspace.

Ashbaugh’s etchings, which allude to the potent allure and taboo of Genetic Manipulation, are both counterpoint and companion-piece to the Text. Printed on beautiful rag paper, their texture, odor, form, weight, and color are qualities unavailable to the Text in cyberspace. (The etchings themselves will undergo certain irreparable changes following their initial viewing.)

This Artist’s Book (which is not exactly a “book” at all) is cased in a wrought metal box, the Mechanism, which in itself becomes a crucial, integral element of the Text. This book-as-object raises unique questions about Art, Time, Memory, Possession—and the Politics of Information Control. It will be the first Digital Myth.

William Gibson had been friends with Dennis Ashbaugh for some time, ever since the latter had written him an admiring letter a few years after his landmark novel Neuromancer was published. The two men worked in different mediums, but they shared an interest in the transformations that digital technology and computer networking were having on society. They corresponded regularly, although they met only once in person.

Yet it was neither Gibson the literary nor Ashbaugh the visual artist who conceived their joint project’s central conceit; it was instead none other than the author of the prospectus above, publisher Kevin Begos, Jr., another friend of Ashbaugh. Ashbaugh, who like Begos was based in New York City, had been looking for a way to collaborate with Gibson, and came to his publisher friend looking for ideas that might be compelling enough to interest such a high-profile science-fiction writer, who lived all the way over in Vancouver, Canada, just about as far away as it was possible to get from New York City and still be in North America. “The idea kind of came out of the blue,” says Begos: “to do a book on a computer disk that destroys itself after you read it.” Gibson, Begos, thought, would be the perfect writer to which to pitch such a project, for he innately understood the kairos moment in art; his writing was thoroughly informed by the underground rhythms of the punk and new-wave music scenes. And, being an acknowledged fan of experimental literature like that written by his hero William S. Burroughs, he wasn’t any stranger to conceptual literary art of the sort which this idea of a self-destroying text constituted.

Even so, Begos says that it took him and Ashbaugh a good six to nine months to convince Gibson to join the project. Even after agreeing to participate, Gibson proved to be the most passive of the trio by far, providing the poem that was to destroy itself early on but then doing essentially nothing else after that. It’s thus ironic and perhaps a little unfair that the finished piece remains today associated almost exclusively with the name of William Gibson. If one person can be said to be the mastermind of the project as a whole, that person must be Kevin Begos, Jr., not William Gibson.

Begos, Ashbaugh, and Gibson decided to call their art project Agrippa (A Book of the Dead), adopting the name Gibson gave to his poem for the project as a whole. Still, there was, as the prospectus above describes, much more to it than the single self-immolating disk which contained the poem. We can think of the whole artwork as being split into two parts: a physical component, provided by Ashbaugh, and a digital component, provided by Gibson, with Begos left to tie them together. Both components were intended to be transitory in their own ways. (Their transcendence, of course, must be in the eye of the beholder.)

Begos said that he would make and sell just 455 copies of the complete work, ranging in price from $450 for the basic edition to $7500 for a “deluxe copy in a bronze case.” The name of William Gibson lent what would otherwise have been just a wacky avant-garde art project a great deal of credibility with the mainstream press. It was discussed far and wide in the spring and summer of 1992, finding its way into publications like People, Entertainment Weekly, Esquire, and USA Today long before it existed as anything but a set of ideas inside the minds of its creators. A reporter for Details magazine repeated the description of a Platonic ideal of Agrippa that Begos relayed to him from his fond imagination:

‘Agrippa’ comes in a rough-hewn black box adorned with a blinking green light and an LCD readout that flickers with an endless stream of decoded DNA. The top opens like a laptop computer, revealing a hologram of a circuit board. Inside is a battered volume, the pages of which are antique rag-paper, bound and singed by hand.

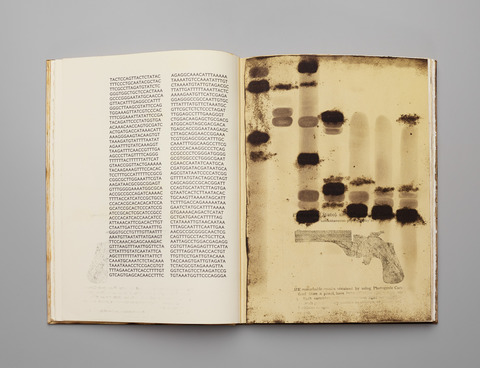

Like a frame of unprocessed film, ‘Agrippa’ begins to mutate the minute it hits the light. Ashbaugh has printed etchings of DNA nucleotides, but then covered them with two separate sets of drawings: One, in ultraviolet ink, disappears when exposed to light for an hour; the other, in infrared ink, only becomes visible after an hour in the light. A paper cavity in the center of the book hides the diskette that contains Gibson’s fiction, digitally encoded for the Macintosh or the IBM.

[…]

The disk contained Gibson’s poem Agrippa: “The story scrolls on the screen at a preset pace. There is no way to slow it down, speed it up, copy it, or remove the encryption that ultimately causes it to disappear.” Once the text scrolled away, the disk got wiped, and that was that. All that would be left of Agrippa was the reader’s memory of it.

The three tricksters delighted over the many paradoxes of their self-destroying creation with punk-rock glee. Ashbaugh laughed about having to send two copies of it to the copyright office — because to register it for a copyright, you had to read it, but when you read it you destroyed it. Gibson imagined some musty academic of the future trying to pry the last copy out of the hands of a collector so he could read it — and thereby destroy it definitively for posterity. He described it as “a cruel joke on book collectors.”

As I’ve already noted, Ashbaugh’s physical side of the Agrippa project was destined to be overshadowed by Gibson’s digital side, to the extent that the former is barely remembered at all today. Part of the problem was the realities of working with physical materials, which conspired to undo much of the original vision for the physical book. The LCD readout and the circuit-board hologram fell by the wayside, as did Ashbaugh’s materializing and de-materializing pictures. (One collector has claimed that the illustrations “fade a bit” over time, but one does have to wonder whether even that is wishful thinking.)

But the biggest reason that one aspect of Agrippa so completely overshadowed the other was ironically the very thing that got the project noticed at all in so many mainstream publications: William Gibson’s fame in comparison to his unknown collaborators. People magazine didn’t even bother to mention that there was anything to Agrippa at all beyond the disk; “I know Ashbaugh was offended by that,” says Begos. Unfortunately obscured by this selective reporting was an intended juxtaposition of old and new forms of print, a commentary on evolving methods of information transmission. Begos was as old-school as publishers got, working with a manual printing press not very dissimilar from the one invented by Gutenberg; each physical edition of Agrippa was a handmade objet d’art. Yet all most people cared about was the little disk hidden inside it.

So, even as the media buzzed with talk about the idea of a digital poem that could only be read once, Begos had a hell of a time selling actual, physical copies of the book. As of December of 1992, a few months after it went to press, Begos said he still had about 350 copies of it sitting around waiting for buyers. It seems unlikely that most of these were ever sold; they were quite likely destroyed in the end, simply because the demand wasn’t there. Begos relates a typical anecdote:

There was a writer from a newspaper in the New York area who was writing something on Agrippa. He was based out on Long Island and I was based in Manhattan. He sent a photographer to photograph the book one afternoon. And he’d done a phone interview with me, though I don’t remember if he called Gibson or not. He checked in with me after the photographer had come to make sure that it had gone alright, and I said yes. I said, “Well aren’t you coming by; don’t you want to see the book?” He said “No; you know, the traffic’s really bad; you know, I just don’t have time.” He published his story the next day, and there was nothing wrong with it, but I found that very odd. It probably would have taken him an hour to drive in, or he could have waited a few days. But some people, they almost seemed resistant to seeing the whole package.

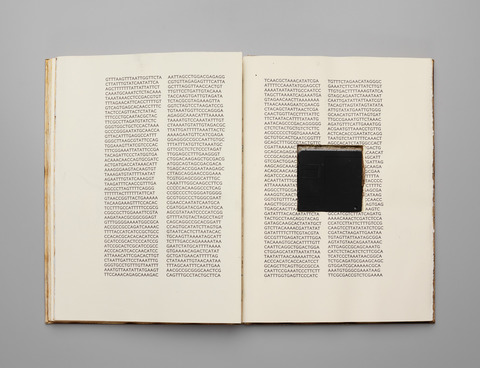

It’s inevitable, given the focus of this site, that our interest too will largely be captured by the digital aspect of the work. Yet the physical artwork — especially the full-fledged $7500 edition — certainly is an interesting creation in its own right. Rather than looking sleek and modern, as one might expect from the package framing a digital text from the prophet of cyberpunk, it looks old — mysteriously, eerily old. “There’s a little bit of a dark side to the Gibson story and the whole mystery about it and the whole notion of a book that destroys itself, a text that destroys itself after you read it,” notes Begos. “So I thought that was fitting.” It smacks of ancient tomes full of forbidden knowledge, like H.P. Lovecraft’s Necronomicon, or the Egyptian Book of the Dead to which its parenthetical title seems to pay homage. Inside was to be found abstract imagery and, in lieu of conventional text, long strings of numbers and characters representing the gene sequence of the fruit fly. And then of course there was the disk, nestled into its little pocket at the back.

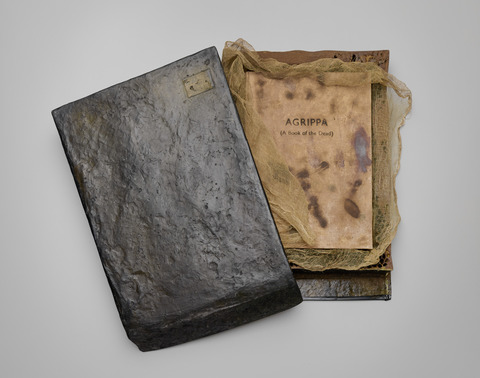

The deluxe edition of Agrippa is housed in this box, made out of fiberglass and paper and “distressed” by hand.

The book’s 64 hand-cut pages combine long chunks of the fruit-fly genome alongside Daniel Ashbaugh’s images evocative of genetics — and occasional images, such as the pistol above, drawn from Gibson’s poem of “Agrippa.”

The last 20 pages have been glued together — as usual, by hand — and a pocket cut out of them to hold the disk.

But it was, as noted, the contents of the disk that really captured the public’s imagination, and that’s where we’ll turn our attention now.

William Gibson’s contribution to the project is an autobiographical poem of approximately 300 lines and 2000 words. The poem called “Agrippa” is named after something far more commonplace than its foreboding packaging might imply. “Agrippa” was actually the brand name of a type of photo album which was sold by Kodak in the early- and mid-twentieth century. Gibson’s poem begins as he has apparently just discovered such an artifact — “a Kodak album of time-burned black construction paper” — in some old attic or junk room. What follows is a meditation on family and memory, on the roots of things that made William Gibson the man he is now. There’s a snapshot of his grandfather’s Appalachian sawmill; there’s a pistol from some semi-forgotten war; there’s a picture of downtown Wheeling, West Virginia, 1917; there’s a magazine advertisement for a Rocket 88; there’s the all-night bus station in Wytheville, Virginia, where a young William Gibson used to go to buy cigarettes for his mother, and from which a slightly older one left for Canada to avoid the Vietnam draft and take up the life of an itinerant hippie.

Gibson is a fine writer, and “Agrippa” is a lovely, elegiac piece of work which stands on its own just fine as plain old text on the page when it’s divorced from all of its elaborate packaging and the work of conceptual art that was its original means of transmission. (Really, it does: go read it.) It was also the least science-fictional thing he had written to date — quite an irony in light of all of the discussion that swirled around it about publication in the age of cyberspace. But then, the ironies truly pile up in layers when it comes to this artistic project. It was ironically appropriate that William Gibson, a famously private person, should write something so deeply personal only in the form of a poem designed to disappear as soon as it had been read. And perhaps the supreme irony was this disappearing poem’s interest in the memories encoded by permanent artifacts like an old photo album, an old camera, or an old pistol. This interest in the way that everyday objects come to embody our collective memory would go on to become a recurring theme in Gibson’s later, more mature, less overtly cyberpunky novels. See, for example, the collector of early Sinclair microcomputers who plays a prominent role in 2003’s Pattern Recognition, in my opinion Gibson’s best single novel to date.

But of course it wasn’t as if the public’s interest in Agrippa was grounded in literary appreciation of Gibson’s poem, any more than it was in artistic appreciation of the physical artwork that surrounded it. All of that was rather beside the point of the mainstream narrative — and thus we still haven’t really engaged with the reason that Agrippa was getting write-ups in the likes of People magazine. Beyond the star value lent the project by William Gibson, all of the interest in Agrippa was spawned by this idea of a text — it could been have any text packaged in any old way, if we’re being brutally honest — that consumed itself as it was being read. This aspect of it seemed to have a deep resonance with things that were currently happening in society writ large, even if few could clarify precisely what those things were in a world perched on the precipice of the Internet Age. And, for all that the poem itself belied his reputation as a writer of science fiction, this aspect of Agrippa also resonated with the previous work of William Gibson, the mainstream media’s go-to spokesman for the (post)modern condition.

Enter, then, the fourth important contributor to Agrippa, a shadowy character who has chosen to remain anonymous to this day and whom we shall therefore call simply the Hacker. He apparently worked at Bolt, Beranek, and Newman, a Boston consulting firm with a rich hacking heritage (Will Crowther of Adventure fame had worked there), and was a friend of Dennis Ashbaugh. Kevin Begos, Jr., contracted with him to write the code for Gibson’s magical disappearing poem. “Dealing with the hacker who did the program has been like dealing with a character from one of your books,” wrote Begos to Gibson in a letter.

The Hacker spent most of his time not coding the actual display of the text — a trivial exercise — but rather devising an encryption scheme to make it impenetrable to the inevitable army of hex-editor-wielding compatriots who would try to extract the text from the code surrounding it. “The encryption,” he wrote to Begos, “has a very interesting feature in that it is context-sensitive. The value, both character and numerical, of any given character is determined by the characters next to it, which from a crypto-analysis or code-breaking point of view is an utter nightmare.”

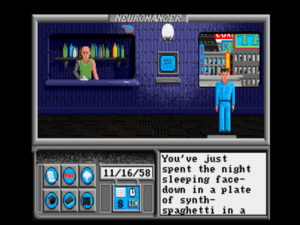

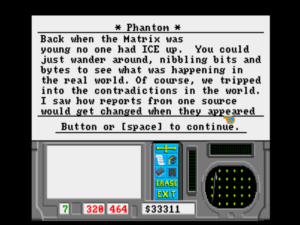

The Hacker also had to devise a protection scheme to prevent people from simply copying the disk, then running the program from the copy. He tried to add digitized images of some of Ashbaugh’s art to the display, which would have had a welcome unifying effect on an artistic statement that too often seemed to reflect the individual preoccupations of Begos, Ashbaugh, and Gibson rather than a coherent single vision. In the end, however, he gave that scheme up as technically unfeasible. Instead he settled for a few digitized sound effects and a single image of a Kodak Agrippa photo album, displayed as the title screen before the text of the poem began to scroll. Below you can see what he ended up creating, exactly as someone would have who was foolhardy enough to put the disk into her Macintosh back in 1992.

The denizens of cyberspace, many of whom regarded William Gibson more as a god than a prophet, were naturally intrigued by Agrippa from the start, not least thanks to the implicit challenge it presented to crack the protection and thus turn this artistic monument to impermanence into its opposite. The Hacker sent Begos samples of the debates raging on the pre-World Wide Web Internet already in April of 1992, months before the book’s publication.

“I just read about William Gibson’s new book Agrippa (The Book of the Dead),” wrote one netizen. “I understand it’s going to be published on disk, with a virus that prevents it from being printed out. What do people think of this idea?”

“I seem to recall reading that this stuff about the virus-loaded book was an April Fools joke started here on the Internet,” replied another. “But nobody’s stopped talk about it, and even Tom Maddox, who knows Gibson, seemed to confirm its existence. Will the person who posted the original message please confirm or confess? Was this an April Fools joke or not?”

The Tom Maddox in question, who was indeed personally acquainted with Gibson, replied that the disappearing text “was part of a limited-edition, expensive artwork that Gibson believes was totally subscribed before ‘publication.’ Someone will publish it in more accessible form, I believe (and it will be interesting to see what the cyberpunk audience makes of it — it’s an autobiographical poem, about ten pages long).”

“What a strange world we live in,” concluded another netizen. Indeed.

The others making Agrippa didn’t need the Hacker to tell them with what enthusiasm the denizens of cyberspace would attack his code, vying for the cred that would come with being the first to break it. John Perry Barlow, a technology activist and co-founder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, told Begos that unidentified “friends of his vow to buy and then run Agrippa through a Cray supercomputer to capture the code and crack the program.”

And yet for the first few months after the physical book’s release it remained uncracked. The thing was just so darn expensive, and the few museum curators and rare-books collectors who bought copies neither ran in the same circles as the hacking community nor were likely to entrust their precious disks to one of them.

Interest in the digital component of Agrippa remained high in the press, however, and, just as Tom Maddox had suspected all along, the collaborators eventually decided to give people unwilling to spend hundreds or thousands of dollars on the physical edition a chance to read — and to hear — William Gibson’s poem through another ephemeral electronic medium. On December 9, 1992, the Americas Society of New York City hosted an event called “The Transmission,” in which the magician and comedian Penn Jillette read the text of the poem as it scrolled across a big screen, bookended by question-and-answer sessions with Kevin Begos, Jr., the only member of the artistic trio behind Agrippa to appear at the event. The proceedings were broadcast via a closed-circuit satellite hookup to, as the press release claimed, “a street-corner shopfront on the Lower East Side, the Michael Carlos Museum in Atlanta, the Kitchen in New York City, a sheep farm in the Australian Outback, and others.” Continuing with the juxtaposition of old and new that had always been such a big thematic part of the Agrippa project — if a largely unremarked one — the press release pitched the event as a return to the days when catching a live transmission of one form or another had been the only way to hear a story, an era that had been consigned to the past by the audio- and videocassette.

When did you last hear Hopalong Cassidy on his NBC radio program? When did you last read to your children around a campfire? Have you been sorry that your busy schedule prevented a visit to the elders’ mud hut in New Guinea, where legends of times past are recounted? Have you ever looked closely at your telephone cable to determine exactly how voices and images can come out of the tiny fibers?

Naturally, recording devices were strictly prohibited at the event. Agrippa was still intended to be an ephemeral kairos moment, just like the radio broadcasts of yore.

Of course, it had always been silly to imagine that all traces of the poem could truly be blotted from existence after it had been viewed and/or heard by a privileged few. After all, people reading it on their monitor screens at home could buy video cameras too. Far from denying this reality, Begos imagined an eventual underground trade in fuzzy Agrippa videotapes, much like the bootleg concert tapes traded among fans of Bob Dylan and the Grateful Dead. Continuing with the example set by those artists, he imagined the bootleg trade being more likely to help than to hurt Agrippa‘s cultural cachet. But it would never come to that — for, despite Begos’s halfhearted precautions, the Transmission itself was captured as it happened.

Begos had hired a trio of student entrepreneurs from New York University’s Interactive Television Program to run the technical means of transmission of the Transmission. They went by the fanciful names of “Templar, Rosehammer, and Pseudophred” — names that could have been found in the pages of a William Gibson novel, and that should therefore have set off warning bells in the head of one Kevin Begos, Jr. Sure enough, the trio slipped a videotape into the camera broadcasting the proceedings. The very next morning, the text of the poem appeared on an underground computer bulletin board called MindVox, preceded by the following introduction:

Hacked & Cracked by

-Templar-

Rosehammer & Pseudophred

Introduction by TemplarWhen I first heard about an electronic book by William Gibson… sealed in an ominous tome of genetic code which smudges to the touch… which is encrypted and automatically self-destructs after one reading… priced at $1,500… I knew that it was a challenge, or dare, that would not go unnoticed. As recent buzzing on the Internet shows, as well as many overt attempts to hack the file… and the transmission lines… it’s the latest golden fleece, if you will, of the hacking community.

I now present to you, with apologies to William Gibson, the full text of AGRIPPA. It, of course, does not include the wonderful etchings, and I highly recommend purchasing the original book (a cheaper version is now available for $500). Enjoy.

And I’m not telling you how I did it. Nyah.

As Matthew Kirschenbaum, the foremost scholar of Agrippa, points out, there’s a delicious parallel to be made with the opening lines of Gibson’s 1981 short story “Johnny Mnemonic,” the first fully realized piece of cyberpunk literature he or anyone else ever penned: “I put the shotgun in an Adidas bag and padded it out with four pairs of tennis socks, not my style at all, but that was what I was aiming for: If they think you’re crude, go technical; if they think you’re technical, go crude. I’m a very technical boy. So I decided to get as crude as possible.” Templar was happy to let people believe he had reverse-engineered the Hacker’s ingenious encryption, but in reality his “hack” had consisted only of a fortuitous job contract and a furtively loaded videotape. Whatever works, right? “A hacker always takes the path of least resistance,” said Templar years later. “And it is a lot easier to ‘hack’ a person than a machine.”

Here, then, is one more irony to add to the collection. Rather than John Parry Barlow’s Cray supercomputer, rather than some genius hacker Gibson would later imagine had “cracked the supposedly uncrackable code,” rather than the “international legion of computer hackers” which the journal Cyberreader later claimed had done the job, Agrippa was “cracked” by a cameraman who caught a lucky break. Within days, it was everywhere in cyberspace. Within a month, it was old news online.

Before Kirschenbaum uncovered the real story, it had indeed been assumed for years, even by the makers of Agrippa, that the Hacker’s encryption had been cracked, and that this had led to its widespread distribution on the Internet — led to this supposedly ephemeral text becoming as permanent as anything in our digital age. In reality, though, it appears that the Hacker’s protection wasn’t cracked at all until long after it mattered. In 2012, the University of Toronto sponsored a contest to crack the protection, which was won in fairly short order by one Robert Xiao. Without taking anything away from his achievement, it should be noted that he had access to resources — including emulators, disk images, and exponentially more sheer computing power — of which someone trying to crack the program on a real Macintosh in 1992 could hardly even have conceived. No protection is unbreakable, but the Hacker’s was certainly unbreakable enough for its purpose.

And so, with Xiao’s exhaustive analysis of the Hacker’s protection (“a very straightforward in-house ‘encryption’ algorithm that encodes data in 3-byte blocks”), the last bit of mystery surrounding Agrippa has been peeled away. How, we might ask at this juncture, does it hold up as a piece of art?

My own opinion is that, when divorced from its cultural reception and judged strictly as a self-standing artwork of the sort we might view in a museum, it doesn’t hold up all that well. This was a project pursued largely through correspondence by three artists who were all chasing somewhat different thematic goals, and it shows in the end result. It’s very hard to construct a coherent narrative of why all of these different elements are put together in this way. What do Ashbaugh’s DNA texts and paintings really have to do with Gibson’s meditation on family memory? (Begos made a noble attempt to answer that question at the Transmission, claiming that recordings of DNA strands would somehow become the future’s version of family snapshots — but if you’re buying that, I have some choice swampland to sell you.) And then, why is the whole thing packaged to look like H.P. Lovecraft’s Necronomicon? Rather than a unified artistic statement, Agrippa is a hodgepodge of ideas that too often pull against one another.

But is it really fair to divorce Agrippa so completely from its cultural reception all those years ago? Or, to put it another way, is it fair to judge Agrippa the artwork based solely upon Agrippa the slightly underwhelming material object? Matthew Kirschenbaum says that “the practical failure to realize much of what was initially planned for Agrippa allowed the project to succeed by leaving in its place the purest form of virtual work — a meme rather than an artifact.” He goes on to note that Agrippa is “as much conceptual art as anything else.” I agree with him on both points, as I do with the online commenter from back in the day who called it “a piece of emergent performance art.” If art truly lives in our memory and our consciousness, then perhaps our opinion of Agrippa really should encompass the whole experience, including its transmission and its reception. Certainly this is the theory that underlies the whole notion of conceptual art — whether the artwork in question involves flying cows or disappearing poems.

It’s ironic — yes, there’s that word again — to note that Agrippa was once seen as an ominous harbinger of the digital future in the way that it showed information, divorced from physical media, simply disappearing into the ether, when the reality of the digital age has led to exactly the opposite problem, with every action we take and every word we write online being compiled into a permanent record of who we supposedly are — a slate which we can never wipe clean. And this digital permanence has come to apply to the poem of “Agrippa” as well, which today is never more than a search query away. Gibson:

The whole thing really was an experiment to see just what would happen. That whole Agrippa project was completely based on “let’s do this. What will happen?” Something happens. “What’s going to happen next?”

It’s only a couple thousand words long, and dangerously like poetry. Another cool thing was getting a bunch of net-heads to sit around and read poetry. I sort of liked that.

Having it wind up in permanent form, sort of like a Chinese Wall in cyberspace… anybody who wants to can go and read it, if they take the trouble. Free copies to everyone. So that it became, really, at the last minute, the opposite of the really weird, elitist thing many people thought it was.

So, Agrippa really was as uncontrollable and unpredictable for its creators as it was for anyone else. Notably, nobody made any money whatsoever off it, despite all the publicity and excitement it generated. In fact, Begos calls it a “financial disaster” for his company; the fallout soon forced him to abandon publishing altogether.

“Gibson thinks of it [Agrippa] as becoming a memory, which he believes is more real than anything you can actually see,” said Begos in a contemporary interview. Agrippa did indeed become a collective kairos moment for an emerging digital culture, a memory that will remain with us for a long, long time to come. Chris in the Morning would be proud.

(Sources: the book Mechanisms: New Media and the Forensic Imagination by Matthew G. Kirschenbaum; Starlog of September 1994; Details of June 1992; New York Times of November 18 1992. Most of all, The Agrippa Files of The University of California Santa Barbara, a huge archive of primary and secondary sources dealing with Agrippa, including the video of the original program in action on a vintage Macintosh.)