At the end of 1984 Alan Miller and Bob Whitehead, two of the members of Atari’s Fantastic Four who had founded Activision along with Jim Levy, split away from the latter company to form yet another, Accolade. I must admit that their publicly stated reasons for doing so strike me as a bit difficult to understand. In a fairly recent article in Retro Gamer magazine, the two say that Activision was “too entrenched in its console roots” for their tastes, an odd claim to make considering that Activision 2.0 had just had a huge hit on computers with Ghostbusters and that virtually all new development was focused in that direction. In another interview, Miller states he was “puzzled why Activision couldn’t make a profit,” which may point to concerns with Levy’s management. Or the whole thing may have come down to personal conflicts that everyone is too diplomatic to discuss. Regardless, Miller and Whitehead made the bold decision to start their own company at a seemingly terrible time, just as established publisher after established publisher was dying. With no one in the financial sector willing to touch home-computer software with the proverbial ten-foot pole, they financed the venture entirely by themselves, drawing on their savings from the glory days of Activision 1.0, when the games they had created for the Atari VCS had sold in the hundreds of thousands or millions, with royalty checks to match. With Larry Kaplan having been lured back to Atari in 1982, their departure left only David Crane and Jim Levy at Activision from among the founders. In two or three more years they too would be gone.

Tellingly, Miller and Whitehead’s first creative hire was not a programmer or designer but rather Mimi Doggett, a talented graphic artist who had spent more than four years with Atari. She would help Accolade walk a fine line between innovation and commercial appeal with markedly more success than Activision 2.0 would manage over the next several years. Accolade excelled at finding subject matter that was unexplored or done only badly by other games, but which nevertheless had plenty of potential mass appeal; they had none of Activision 2.0’s more avant-garde tendencies. They implemented gameplay around their fictional conceits that was always fast-paced, accessible, and not too time-consuming if you didn’t want it to be, but that also always allowed for at least a modicum of depth — Trip Hawkins’s old formulation of “simple, hot, and deep” writ larger than Electronic Arts themselves often managed. Miller:

Games should be worn by the user without feeling like they’re wearing them. They should be intuitively obvious to use, and as transparent as possible to the user. The user should feel that they’re in an experience.

The cherry on top was graphics that were often technically spectacular, especially on Accolade’s bread-and-butter platform the Commodore 64 (this despite Accolade being located almost next door to Apple’s headquarters in Cupertino), but which also sported an unusually refined aesthetic sensibility thanks to Doggett. The same sensibility extended to the packaging, which would be shortlisted for a Clio Award in 1987. Accolade’s early output evinces none of the fit-and-finish problems that so often plagued Activision 2.0, being uniformly polished to a mirror shine. They were rewarded with a stellar reputation among Commodore owners in particular; a new Accolade game was guaranteed to sell — and, of course, to be widely pirated — based simply on the name on the box.

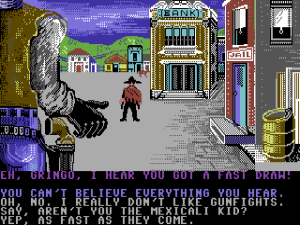

Accolade’s two 1985 launch titles, one designed and programmed by each of the founders with the invaluable assistance of Doggett, were already fine examples of the approach that would come to define the company. Miller’s Law of the West was a cowboy western, a genre that, while amply explored in arcade games like Gun Fight and Boot Hill, was much less common in computer games. As a new sheriff in town, you wander the streets talking with the citizens and solving problems, sometimes just with conversation, sometimes with your trusty six-shooter. The additional layer of strategy and narrative texture afforded by the conversations would prove to be typical of Accolade games to come, which were almost never just simple action games. Whitehead’s Hardball, meanwhile, was a wonderfully attractive and playable action-oriented baseball game, a sport which had previously been explored only badly or through dry statistics-based simulations like SSI’s Computer Baseball.

As soon as Accolade established themselves with Law of the West and Hardball, both of which became big hits and made the company profitable in rather astonishingly short order, they began seeking outside developers with a similar sensibility whose work they could publish to supplement their in-house games. One of the first and most long-lived of these relationships would be the one with the tiny Ottawa-based house Artech.

Founded in 1981 by Rick Banks and Paul Butler, Artech already had a considerable resume to their credit before partnering with Accolade. The company had been born as a developer of games for the NABU Network, an early effort to deliver computer content through Ottawa’s cable-television lines that’s been billed — sometimes slightly overbilled in my opinion, but that’s as may be — as “the Internet, ten years ahead of its time.” Artech’s secret weapon, acquired soon after the deal with NABU, was Michael Bate, a colorful self-proclaimed “ideas man” with a degree in music who had already worked as a journalist, a radio producer, a pedal-steel player in a country band, and a railroad brakeman. He personally designed most of the NABU games, which were then programmed largely by Banks and Butler.

One of Artech’s most popular games for NABU featured B.C., the lead character of the long-running newspaper comic strip of the same name. Artech’s work for NABU got them noticed by Sydney Development Corporation, a Vancouver-based company with fingers in lots of computer-industry pies, from project management to retail stores, that now dreamed of becoming Canada’s first major home-computer software developer. Sydney scooped Artech up to become their “Video Games/Educational Software Division” in the spring of 1983. The first game the team made for Sydney once again featured B.C. Published by Sierra for most viable home computers of the era as well as the ColecoVision console, B.C.’s Quest for Tires became a big hit not only in Canada but also in the United States and Europe. (Our old friend Chuck Benton of Softporn fame would do some of the ports.)

Within a year or two Bate would declare he wasn’t “overly proud” of B.C.’s Quest for Tires, produced as it was quickly under the stipulations of a licensing agreement. Luckily, the parent company in Vancouver largely stepped back after that and gave the little group in Ottawa remarkable freedom to make whatever games they wanted to make. Sydney’s management had enough problems of their own, finding themselves caught in an economic downward spiral as the home-computer industry crashed and reams of overambitious plans fell through. This left the games division as the only division of the company actually making money. By 1987 the group that had once been Artech would become Artech once more, managing to extricate themselves from the grip of their dying parent and become an independent company once again; this second Artech incarnation would last until 2011.

Meanwhile, and under whatever name, there were games to be made. The once and future Artech really came into their own with a pair of World War II air-combat games, Dam Busters (1985) and Ace of Aces (1986), that were amongst the first outside productions to be published by Accolade. They fit perfectly with the general Accolade aesthetic, being very accessible and audiovisually impressive games that recreated unusual crannies of every gamer’s favorite war that set them a little apart. Dam Busters put the player in charge not of the typical B-17 but rather of an RAF Lancaster night bomber trying to destroy a German dam using one of Barnes Wallis’s “bouncing bombs.” Ace of Aces, meanwhile, put her behind the controls not of the usual P-51 or P-38 but of a Mosquito fighter-bomber. Uninterested in the technical minutiae of flight and military hardware that enthralled companies like subLOGIC and MicroProse, Bate nevertheless did extensive research to create “aesthetic simulations of historical events,” what he called “docu-games” that tried to capture the spirit of their subjects, like a good movie; Dam Busters was in fact directly inspired by the 1955 classic of the same name. Artech and Accolade were amply rewarded for their efforts: Ace of Aces alone sold over 500,000 copies between North America and Europe during its commercial lifetime. Given numbers like that, later efforts from Artech like Apollo 18 and The Train, both released in 1987, understandably continued in largely the same vein. The latter, a crazy chase across Nazi-occupied France, is in the reckoning of many Artech’s 8-bit masterpiece. It really does play like a great old-school war flick — appropriately so, since it was loosely based on a 1964 Burt Lancaster vehicle.

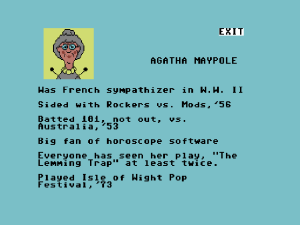

If The Train is Artech’s predictable masterpiece, the ultimate expression of their established approach, 1986’s Killed Until Dead, whose design is credited jointly to Michael Bate and Rick Banks, is their wonderfully unique outlier. It’s very unusual indeed as both an Accolade and an Artech production in that it has no action elements at all. While, as Paul Butler once joked, Artech’s usual target demographic was “teenage boys, ages 12 to 45,” Killed Until Dead feels pointed in a different direction. The 21 snack-sized mysteries it offers all take place at a meeting of the Murder Club, a stand-in for the Detection Club that created The Scoop. Its five members are each (fictional) established mystery writers, modeled on various famous figures in the fictional and nonfictional history of murder: Mike Stammer (Mickey Spillane’s detective Mike Hammer), Agatha Maypole (a hybrid of Agatha Christie and her sleuth Miss Marple), Lord Peter Flimsey (Dorothy L Sayers’s detective Lord Peter Wimsey), Sydney Meanstreet (a hybrid of Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe and actor Sydney Greenstreet, who played him on the radio), and Claudia von Bulow (a feminine version of accused murderer Claus von Bülow). Your own detective is Hercule Holmes, a name whose antecedents I trust need no explanation.

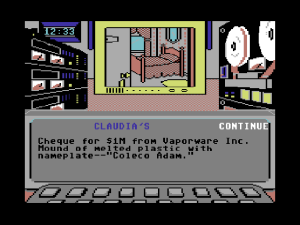

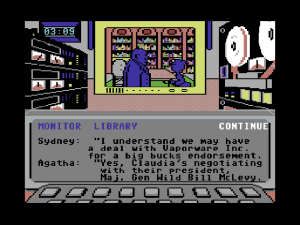

To add an interesting twist to the usual proceedings, you aren’t trying to solve a murder here but rather to prevent one Murder Club member from killing another; who the potential killer and victim will be will of course vary from episode to episode. The deeply creepy means you use to accomplish this is a spying setup to die for. You’ve not only bugged the writers’ rooms as well as other areas of the mansion at which they’re staying for both video and audio, but you’ve also got a master key that lets you get into their rooms when they’re out. The twelve hours of game time you have to solve each mystery takes about thirty minutes of real time; once you start a mystery, the clock is always ticking. As you quickly discover after settling in with your first mystery or two, each episode follows a fairly predictable pattern. First you break into all of the suspects’ rooms to see what they’re up to. This should reveal some information about various planned liaisons, which you’ll want to view live and/or record; in the later, more difficult mysteries in particular, there will often be two meetings taking place at the same time, making your ability to record one while you view another essential. Next you’ll want to call some or all of the suspects on the telephone to see what you can shake loose; they’ll also call you from time to time to further their own agendas, whether by offering useful tips or trying to put you off the scent (such misleading information can be as useful as any other if you can read between the lines). Finally, with all of the information you’ve compiled from all of the above, plus each suspect’s background dossier, you should be able to deduce murderer, victim, weapon, and motive and stop the crime by calling the murderer up and accusing her before the clock strikes midnight and she does the deed — and does you in for good measure (you can’t really blame her for that considering the spying you’ve been up to).

The NSA can only dream of a setup like this one. And if you don’t get the reference to “Wild Bill,” well, keep reading this blog. We’ll get there soon enough.

Killed Until Dead is steeped in the heritage of mystery, murder, and cozy mayhem, the whole game an extended, meta-textual love letter to its genre that crime-fiction aficionados will sink into like a warm blanket. Its most controversial design choice then and now is the mechanism for forcing your way into each suspect’s room: you have to answer a multiple-choice trivia question about the gloriously macabre history of murder on page, screen, and sometimes even real life. Certainly such a requiring of outside knowledge is a questionable choice by most modern standards of design. For all that, though, I wouldn’t want to lose the questions; they just give this loving homage of a game that much more opportunity to spread the love. Nowadays if you don’t know the name of Sam Spade’s partner (Miles Archer) or what Hitchcock used to fake the blood in Psycho‘s shower scene (it was chocolate syrup; luckily he was shooting in black and white), well, that sort of thing is only a Google search away. (Admittedly, the rabbit holes your searches lead you down may end up consuming more time than the cases themselves.) Or just make your best guess, and come back again in thirty minutes (game time) if you’re wrong; there’s enough time to spare that you’ll probably be okay.

Indeed, none of the cases, not even those of “Super Sleuth” level, are really all that difficult. When Dorte and I played we failed to solve one or two early on when we were just getting the hang of things, but once we understood the pattern of play we solved every case with relative ease. And on the whole I think that’s fine; I believe it’s far, far better for a game like this one to be too easy than too hard. There are obvious similarities here to other short-form mystery games that use the same setting, cast of characters, and props over and over again in the service of different cases, like Murder on the Zinderneuf or for that matter Cluedo. But what separates Killed Until Dead from the likes of “Colonel Mustard in the library with the candlestick” is Artech’s decision not to try to randomly generate the individual permutations. Each case is carefully, lovingly, handcrafted, with gobs of wit and charm; Dorte liked Miss Maypole so much that she’d just start giggling every time the fussy old bat would enter the picture. The best decision Artech made for Killed Until Dead was the one to spend lots of time designing the 21 bespoke cases rather than wrestling with a random case generator that would almost inevitably disappoint. The disadvantage of their approach is of course that it makes Killed Until Dead a very finite experience; once you’ve played the 21 cases there’s nothing else to be done. This was a bigger concern in 1986, when games were expensive, and, especially for many younger players without the financial wherewithal to buy them very often, needed to last a long, long time. Nowadays it’s really no concern at all. By my lights, this game has just about the perfect amount of content, ending just when all of the potential has been pretty much wrung out of its repeating stage, actors, and props.

Killed Until Dead is a little delight of a game that I highly recommend. It offers attractive graphics and that level of refined, casual playability that had already by 1986 become such a trademark of Accolade. And it offers that little something extra, love for its chosen genre. In fact, I realize now that I’ve used some variation of the word “love” several times in describing Killed Until Dead. Love for a topic combined with a sense of fair play and a willingness to polish, polish, polish will take a game designer a long way. Feel free to download it and load it up in your favorite Commodore 64 emulator. (A tip for users of VICE: turn off “True Drive Emulation” to make the normally unbearable Commodore loading times barely noticeable.) It makes for a great way to spend a few cozy winter evenings.

(Print sources for this article include the November 1986 and October 1987, Computer Gaming World, the November 1985 Family Computing, the August 1985 Zzap!, the November 1985 Sinclair User, Retro Gamer 50, the Arcade Express dated May 8 1983, and the Ottawa Citizen from May 31 1982, August 28 1982, September 20 1983, and September 29 1983, and February 15 2007. More information on NABU can be found at IEEE Canada and York University.)