By the point in late 1988 when Magnetic Scrolls released Fish!, their fifth text adventure and arguably their best yet, a distressing pattern of diminishing returns had already been well-established when it came to sales. Anita Sinclair’s little collective had peaked early in commercial if not in design terms, with the release of the illustrated version of their first game The Pawn in 1986. Indeed, alongside Infocom’s Leather Goddesses of Phobos, The Pawn had that year become one of the last two text adventures ever to generate sales sufficient to make the games industry at large sit up and pay attention. The performance of neither game had had all that much to do with its intrinsic design merits: sales of The Pawn had been driven by the timely appeal of its pretty pictures to people looking to show off their new Atari STs and Commodore Amigas, sales of Leather Goddesses by the timeless allure of sex to the largely adolescent male audience for computer games in general. Nevertheless, while for Infocom the year had been a welcome final hurrah that may very well have staved off their inevitable endgame for a year or more, for Magnetic Scrolls it had simply been one heck of an auspicious start.

Sadly, for both companies it would all be downhill from there. Guild of Thieves, Magnetic Scrolls’s follow-up to The Pawn, did quite well in its own right, but nowhere near as well as its predecessor. A pattern was soon established of each successive game selling a little less than the previous. Magnetic Scrolls’s relationship with their publisher Rainbird steadily deteriorated in cadence with their diminishing sales numbers. Anita Sinclair, who even her most supportive colleagues acknowledged could be difficult at times, never got on very well with Paula Byrne, the woman who was now her primary contact at the label her good friend Tony Rainbird had founded and lent his name to but had left already in late 1986. In a surprisingly frank 1989 statement to the German magazine Aktueller Software Markt, Byrne admitted publicly that she “didn’t have a very good relationship with Anita. Anita had much preferred to work with Tony Rainbird.” When in May of 1989 — just after that interview — Rainbird was acquired by the American publisher MicroProse, Magnetic Scrolls was promptly cut loose. Given her poor relationship with Anita Sinclair and the declining sales of Magnetic Scrolls’s games, Byrne had little motivation to argue with her new bosses’ decision.

For most small developers, that event, described by Anita Sinclair herself as an “horrendous collapse,” would have marked the death knell. With the rights to all of their extant games tied to Rainbird, who were no longer interested in selling them, Magnetic Scrolls no longer had any income whatsoever. Nor were they in much of a position to make new hits to generate new income. All of Magnetic Scrolls’s development technology and wisdom were still tied to text adventures, a genre the conventional wisdom said was dead as a commercial proposition; both Infocom and Level 9, the other two significant remaining practitioners of adventures in English text, were getting out of that game entirely as well at the instant that Rainbird decided to wash their hands of Magnetic Scrolls. But thanks to the familial wealth that had always been Magnetic Scrolls’s secret trump card — even during its peak years of 1986 and 1987, the company had never made all that much money in relation to its considerable expenses — Anita Sinclair could elect to play on a bit longer where Infocom and Level 9, under the thumb of corporate parent Mediagenic and perpetually pinched for cash respectively, had had no choice but to fold their hands. She launched a lawsuit against Rainbird/MicroProse, alleging mishandling of her company’s games and seeking restoration of the rights to the back catalog amidst other damages. At the same time, and despite being without a publisher, she poured all the resources she had into a big development project — in fact, the biggest such project Magnetic Scrolls had ever attempted, and by a virtual order of magnitude at that. Begun well before the release of Fish! and the split with Rainbird, in the wake of recent events it was elevated from an important initiative to a save-the-company Hail Mary.

Actually, this single grand project is better seen as three projects built on top of one another, with an actual game, the top layer of this layer cake of technology that would finally emerge as Magnetic Scrolls’s swansong, the least taxing of the lot to develop.

The most taxing of the layers, by contrast, was the one at the bottom. It had nothing intrinsically to do with games at all. Magnetic Windows was rather to be a generic system for creating and running modern GUI-based applications on MS-DOS, the Apple Macintosh, the Commodore Amiga, the Atari ST, and the Acorn Archimedes, allowing programmers to share much of the same code across these very different platforms. It will perhaps convey some sense of the sheer ambition of this undertaking to note that its most obvious analogue was nothing less than Microsoft Windows, a graphical operating environment built on top of MS-DOS which Microsoft had been pushing for years without a lot of success. Admittedly, Magnetic Windows was in some ways less ambitious than Microsoft Windows; it was envisioned as a toolkit for building and running individual GUI applications, not as a full-fledged self-contained operating environment like the Microsoft product. In other ways, however, it was more ambitious; in contrast to the cross-platform Magnetic Windows, Microsoft Windows was targeted strictly at the standard Intel architecture running MS-DOS as its underlying layer, with no support included or planned for alternative platforms.

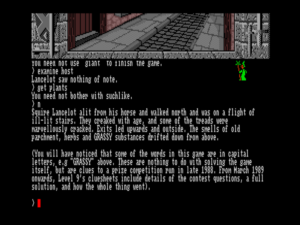

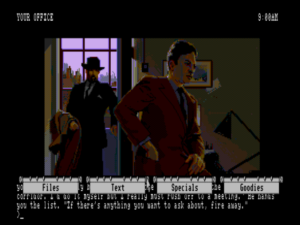

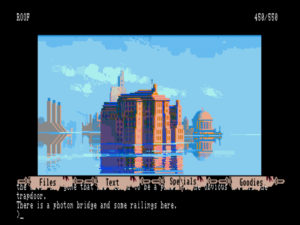

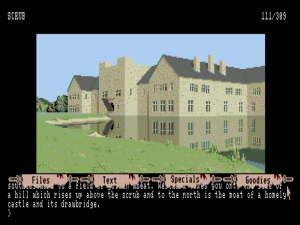

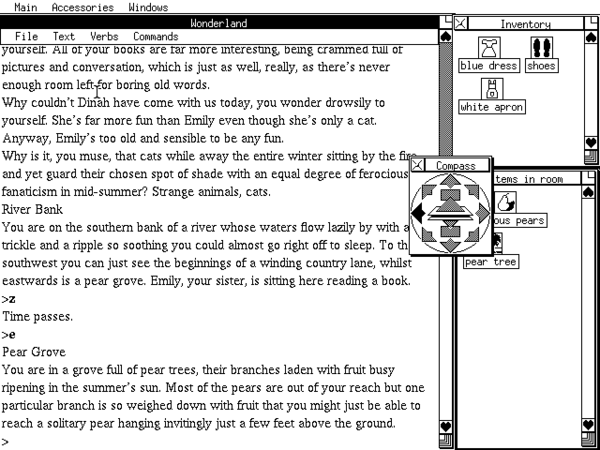

Like most GUI systems of the time, Magnetic Windows owed an awful lot to the Macintosh, as shown in this shot from the game Magnetic Scrolls eventually made using it.

Microsoft Windows, little used and less loved, had been something of a computer-industry laughingstock ever since its initial release back in 1985; it would only start rounding into a truly usable form and gaining traction with everyday users with the release of its version 3.0 in 1990. Once again, its travails only serve to illustrate what a huge technical challenge Magnetic Windows must pose for its own parent company. How could Anita Sinclair’s little staff of half a dozen or so programmers, clever though they doubtless were, hope to succeed where a company with thousands of times the resources had so conspicuously struggled for so long?

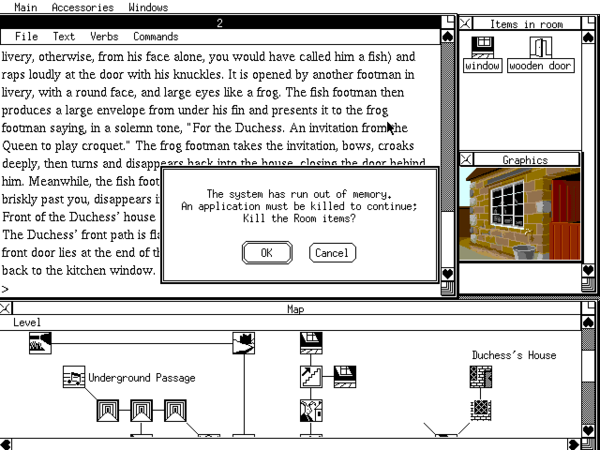

All things considered, they made a pretty good stab at it. Magnetic Windows was a genuinely impressive piece of work, especially considering the shoestring on which it was made and the fact that it had to run on five different platforms. Yet Magnetic Scrolls’s dreams of someday using it to break into business and productivity software, of hopefully licensing it out to many other developers, never stood much of a chance of being realized. Magnetic Windows’s Achilles heel was the same as that which had dogged Microsoft Windows for years: it craved far more computing power than was the norm among average machines of its era. In its MS-DOS version, Magnetic Windows ran responsively only on a pricey high-end 80386-based machine, while on other platforms throwing enough hardware at it to make it a pleasant experience to use was often even more difficult. That the simple text adventure Magnetic Scrolls would eventually make using it would require such high-end hardware would strike many potential buyers, with some justification, as vaguely ridiculous. And as for Magnetic Scrolls’s dreams of world domination in other types of software… well, that was always going to be a steep mountain to climb in the face of Microsoft’s cash reserves, and it only got that much steeper when Microsoft Windows 3.0, at long last the first really complete and usable incarnation of the operating environment, was released the same year as the first product to employ Magnetic Windows.

The middle layer in the cake that would become Magnetic Scrolls’s swansong was the most ambitious expansion of the traditionally humble text-adventure interface to date — indeed, it still remains to this day the most ambitious such expansion ever attempted. Of course, Magnetic Scrolls was hardly alone at the time in working in this general direction. Infocom just before the end had made a concerted attempt to remedy as many as possible of the real or perceived failings of the genre in the eyes of modern players, incorporating into their final run of “graphical interactive fiction” titles things like auto-maps, clickable compass roses, function-key shortcuts, and hint menus along with the now-expected illustrations. Legend Entertainment, Infocom’s implicitly anointed successor, would soon push the general idea yet further via clickable menus of verbs, nouns, and prepositions for building commands without typing, whilst also adding sound and music to the formula.

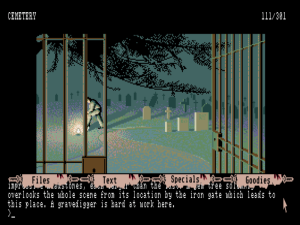

Still, it was Magnetic Scrolls that pushed furthest of all. Taking full advantage of Magnetic Windows, they designed an almost infinitely customizable interface built around individually openable and closable, draggable and sizable windows. The windows could contain all the goodies of late-period Infocom and Legend plus a lot more: text (including for the first time ever an integrated scrollback buffer), graphics (including occasional animated sequences of sometimes surprising length, enough almost to qualify as little cut scenes), lists of objects in the current room and in the player’s inventory (represented as snazzy icons rather than plebeian text), an auto-map (complete with one-click navigation to any location in the game’s world), a compass rose, an extensive hint menu. Performance issues aside, it was all very impressive the first time you fired it up and began to discover its many little nuances. For instance, it was possible to pick up and drop objects by dragging their icons between the objects-in-inventory and objects-in-room windows, while right-clicking one of the object icons opened a menu of likely verbs for use with it — or you could double-click an object to “examine” it via text that appeared in its own separate window. Ditto all this for things depicted in the room illustrations as well. Or, if you liked, you could start with the verb rather than the object in building your command without typing, selecting a verb from a long list of same in the menu bar and then clicking on the object to use with it. Anita Sinclair:

The whole idea of the window system we’ve developed is to take adventures into the next generation. What we found was that people enjoyed the format of text adventures — it is, from a gameplay point of view, the most flexible genre there is — but the problem people had was that when you see a text adventure for the first time, it’s not too obvious where to start or what to do, and the other problem is that people seem to have a huge aversion to typing. So what we wanted to do was to design a system where you can have all the flexibility of a text-adventure game, but with neither of these problems.

The elaborations were extensive enough to qualify today as a fascinating might-have-been in the evolution of the adventure genre as a whole, a middle ground between the text adventures that were and the graphical adventures that were becoming.

At the same time, though, it’s not hard to understand why the approach became an evolutionary dead end: the fact was that almost as soon as you got over being wowed by it all you started to find most of it a little superfluous. While the new interface certainly provided many new ways to do many things, it was highly doubtful whether most of those new ways were really easier than the traditional command line. The dirty little secret of this as well as most efforts in this direction was that they did very little to truly improve the playability of text adventures. Veterans quickly reverted to the clean, efficient command line they had come to know so well, and those newcomers who found the genre interesting enough to stick with it tired almost as quickly of mousing through the fiddly point-and-click interface and learned to use the parser the way the gods of the genre — i.e., Crowther and Woods — had intended it to be used. Meanwhile those who were put off by all the reading and sought, to borrow from Marshall McLuhan, a “hotter” mediated experience weren’t likely to be assuaged for long by all this gilding around a lily that remained at bottom as textual as ever. Seeking a solution to the fundamentally intractable problem of how to keep a genre with such niche appeal as the text adventure at the forefront of a games industry tilting ever more toward the mainstream, Magnetic Scrolls was grasping at straws in telling themselves that a system like this one could represent the “next generation” of adventure games in general. The true next generation in the eyes of most players must be the born-graphical point-and-click adventures of companies like Sierra and Lucasfilm Games, which were just coming into their own as companies like Infocom and Magnetic Scrolls were busily grafting bells and whistles onto their text adventures. In contrast to the games of the former, those of the latter felt like exactly what they were: lipstick on the same old textual swine.

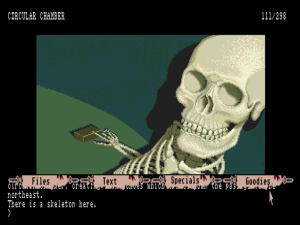

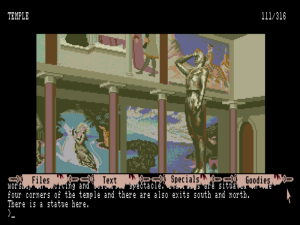

Neat as the new interface was, players who tried to make full use of it spent a lot of time looking at messages like this one.

But what, then, of the topmost layer of our cake, the actual game being surrounded by all this new technology? That game was called Wonderland, and it was given oddly short shrift even by Magnetic Scrolls themselves. Wonderland‘s manual, for instance, spends some three-quarters of its 60-page length exhaustively describing how to use the new windowed interface in general rather than talking all that much about the game buried inside it all. (The times were still such that Magnetic Scrolls felt compelled to start at the very beginning, with chapter titles like “An Introduction to Windowing Environments” and definitions like “icons are small pictures.”) Even today, Wonderland remains among the least discussed and, one senses, least played of the Magnetic Scrolls catalog, being too often dismissed as little more than a dead-end technology demonstration. I must admit that even I never could quite work up the motivation to play it until quite recently, when I tackled it in preparation for this article. Yet what I found when I did so was a game that has a lot more going for it than its reputation would suggest. Yes, on one level it is indeed a dead-end technology demonstration — but that’s far from all it is.

Wonderland was first proposed to Anita Sinclair way back in 1987 by an outsider named David Bishop. At the time, Magnetic Scrolls was already considering the prospect of making a text adventure with a windowed interface. In fact, Sinclair had begun to experiment with that very thing in a game of her own design. “But when I saw Wonderland,” she remembers, “it became obvious that it was a much better game than the one we were working on, and so we shelved that and redefined the ideas that we had for it for Wonderland instead.” Although envisioned from the start as eventually becoming the first game to use the new Magnetic Windows-powered interface, Wonderland was developed using Magnetic Scrolls’s traditional tools while others worked on the other layers of the cake. Only when all of the new technology was completed was the game joined with the new interface that was to sit beneath it. By the time that happened, Wonderland the game had been waiting on the bench for some time, ready to go just as soon as everything else was.

The designer of Wonderland is one of those consummate inside players that can be found kicking around most creative industries, unknown to the public but well-known among his peers, with fingers in a bewildering number of pies. David Bishop had been working at a board-game store in London in the very early 1980s when he had first become aware of the burgeoning world of computer games. Never a programmer, he became something of a pioneer of the role of game designer as a discipline separate from that of game programmer when he formed a partnership with one Chris Palmer, who did know how to program. Together they were responsible for such mid-decade 8-bit hits as Deactivators and Golf Construction Set. His career in game design has continued right up to the present day, coming to encompass just about every popular genre. (That he’s never garnered more public recognition as a designer is perhaps down to the fact that, while he’s designed many successful games, he’s never designed any truly massive, era-defining titles.) Alongside his early efforts in design, he worked for some years as a prominent editor, reviewer, and feature writer for the popular British magazine Computer and Video Games. In years to come, he would add to his titles of game designer and game journalist those of producer, manager, and founder of multiple companies. His one adventure in text, however, has remained Wonderland.

As you may have guessed, Wonderland is based on Alice in Wonderland, that classic Victorian children’s tale by Lewis Carroll that has never lost its charm and fascination for plenty of us adults. In his initial pitch to Magnetic Scrolls, Bishop noted how almost uniquely ideal Alice in Wonderland was for adaptation to an adventure game. Carroll’s novel is about as plot-less as something labeled a story can be; what plot it does have can be summed up as “a thinly characterized little girl named Alice stumbles into a strange magical land and wanders around therein, taking in the sights.” Despite the idealism expressed in the genre’s alternate name of “interactive fiction,” text adventures are far better equipped to deliver this sort of experience than they are to tackle the more elaborate plots typical of most novels. In place of plot, Alice in Wonderland offers an engaging setting filled with humor and intellectual play — the same recipe to which many a classic text adventure has hewed. And to all of these creative advantages must be added the very practical real-world advantage that the works of Lewis Carroll are long out of copyright.

It’s therefore a little strange, as Bishop also mused at the time he was making his proposal, how few adventure games prior to his had tackled Carroll directly. While plenty of authors, including three of the future Infocom Implementors working on the original PDP-10 Zork, had cribbed shamelessly from the master when designing puzzles, games explicitly set in Carroll’s world had been fairly few and far between. The most prominent text adventure among them was the work of one D.A. Asherman, who had written a freeware game with the long-winded title of The Adventures of Alice Who Went through the Looking-Glass and Came Back Not Much Changed that became very popular as a “door game” on many computer bulletin boards. And yet, the love of wordplay that runs through all of Carroll’s work notwithstanding, the most prominent and artistically successful of the interactive Alice in Wonderland adaptations prior to Bishop’s wasn’t a text adventure at all, but rather an action-adventure written by Dale Disharoon for Spinnaker Software’s brief-lived Windham Classics line of children’s literary adaptations — and even that winsomely charming game had been rather overshadowed by the even more winsomely charming Below the Root, also written by Disharoon using the same engine.

David Bishop’s own adaptation of Alice in Wonderland takes the obvious approach, but is none the worse for it. In other words, if Wonderland never transcends its derivative nature, it never embarrasses itself either. After an opening sequence sends you plunging down that famous rabbit hole, you’re left to wander freely through a geography of about 110 rooms, stuffed with all of the expected characters and set-pieces, from a hookah-smoking caterpillar to a grinning cat, from a mad tea party to a decidedly odd game of croquet. (Consciously excluded in the interest of preserving material for a potential sequel were any elements from Through the Looking-Glass, Carroll’s follow-up to Alice in Wonderland, even though the two books are so much of a piece that it’s difficult even for many dedicated Carroll fans to keep track of what comes from which.)

Certainly Bishop had heaps and heaps of great material to work with in turning Alice in Wonderland into a game. Countless bits from the novel are all but screaming to be made into puzzles; not for nothing have variations on the “drink me” potion that makes Alice smaller and the “eat me” cake that makes her bigger appeared in dozens if not hundreds of adventure games over the years. Bishop uses all this raw material well, giving us a big, open, non-linear game with every bit as much appeal as Guild of Thieves, Magnetic Scrolls’s previous best take on this classic old-school approach. As with Guild of Thieves, it’s immensely rewarding to explore Wonderland at your own pace and in your own fashion, poking and prodding, discovering its many unexpected interconnections, solving puzzles and enjoying the dopamine rush each time your score increments on its slow march from 0 to 501.

Best of all, Wonderland, even more so than Guild of Thieves, remains quite consistently fair throughout its considerable breadth. Straightforward puzzles to get you into the swing of things and get some points in the bank gradually give way to more challenging ones that require more careful experimentation with the workings of its world, but there never comes a point where challenge regresses into abuse. When I played it recently, I managed to finish the entire thing without once resorting to the hints. [1]The one puzzle that can perhaps be deemed questionable requires you to manipulate Alice’s own body in a way that will only yield an error message from just about every other text adventure ever made. So, know ye, prospective players, that Wonderland allows you to close and open Alice’s left and right eyes individually. I have to suspect that Wonderland succeeds as it does, despite coming from a company with a very mixed record in the fairness department, because of the inordinately long time it spent in development, for long stretches of which Bishop’s game was largely just sitting around waiting for the layers of technology being built to live beneath it to be completed. The manual lists no fewer than twelve testers, plus an entire outside firm (“Top Star Computer Service”) contracted for the task. This is vastly more attention than was paid to polishing any previous Magnetic Scrolls game, and serves as further confirmation of my longstanding thesis that there is a very nearly linear relationship between the playability of any given adventure game and the amount of testing it received.

After some uncomfortable months in limbo without a publisher, Magnetic Scrolls finally at the tail end of 1989 signed a deal with Virgin Games, a vigorous up-and-comer with the weight of Richard Branson’s transatlantic media empire behind it, to release their still work-in-progress Wonderland along with four more games to follow in the two years after it. Anita Sinclair did her best to create the impression that Magnetic Scrolls and Wonderland had been the subject of a veritable bidding war among publishers. (“You know you’ve cracked it when you’ve got publishers knocking on your door instead of you having to knock on theirs.”) In reality, though, much of the industry had decided that future success lay in getting away from text, and remained skeptical of Magnetic Scrolls’s elaborate hybrid of an adventure game, which despite all the flash still contained some 70,000 good-old-fashioned words to read. The deal with Virgin undoubtedly had much to do with the fact that David Bishop, ever the games industry’s vagabond insider, had himself just signed there as a producer.

Magnetic Scrolls had gone dark for almost the entirety of the previous year in the wake of their jilting by Rainbird, but now greeted 1990 with as much aggressive hype as they could muster, trumpeting their forthcoming return to adventuring prominence and hopefully dominance. The young men who then as now made up the vast majority of gaming journalists were as obliging as ever, jumping at any chance to spend time in the presence of the fetching Anita Sinclair. The result was a blizzard of teasers and previews in virtually every prominent British gaming magazine. Sinclair wasn’t shy about laying it on thick: Wonderland would be “mind-blowing”; Wonderland was “like no adventure you’ve ever seen”; “when you see our next product your eyes are going to pop out.” Her interviewers copied it all down and regurgitated it faithfully in their articles, along with the usual asides about what a hot number their interviewee still was. It was sexist as hell, of course, but Sinclair had the self-assurance to use it to her advantage. There was a reason that Magnetic Scrolls had always enjoyed an enormous amount of free publicity from the magazines, and I’m afraid it wasn’t down to anything intrinsic to the games themselves.

Unfortunately, gamers in general proved markedly less enthused than Anita Sinclair’s smitten interviewers when Wonderland finally shipped for MS-DOS in late 1990, followed by versions for the Amiga, Atari ST, and Acorn Archimedes in 1991 (a planned Macintosh version never materialized). In contrast to the latest purely point-and-click graphical adventures like Lucasfilm’s The Secret of Monkey Island and Sierra’s King’s Quest V, Wonderland struck many as an awkward anachronism. And then of course the performance issues didn’t help. The game ran like a dog on the likes of an Amiga 500, still the heart of the European computer-gaming market. After the better part of a year of constant hype prior to its release, Wonderland disappeared without a trace almost as soon as people could actually walk into a store and buy it.

Having sunk everything into this white elephant of a game, Magnetic Scrolls was now in more serious trouble than ever; there were after all limits even to Anita Sinclair’s financial resources. They would complete just one more product for Virgin. Having recently managed to reacquire their back catalog from Rainbird/MicroProse — the terms of the lawsuit’s settlement otherwise remained undisclosed — they made a Magnetic Scrolls Collection that brought together Guild of Thieves, Corruption, and Fish! under the new Magnetic Windows interface. Dropped by Virgin for their games’ poor sales shortly thereafter, they embarked on a final desperate attempt to switch genres entirely. They started on a game called The Legacy: Realm of Terror, a horror-themed CRPG reminiscent of Dungeon Master, for MicroProse — ironically the very company they had just been suing (whether the publishing deal with MicroProse was connected with the terms of the settlement remains unknown). But Magnetic Scrolls ran completely out of money at last and went out of business well before completing the game; MicroProse wound up turning the work-in-progress over to other developers, who finished it and saw it released in 1993. Most of Magnetic Scrolls’s personnel, including driving force Anita Sinclair, left the games industry for other pursuits after their company shut its doors. “Sometimes I think I would like to write another game,” admitted Sinclair in a 2001 interview which marks one of the vanishingly few times she has spoken publicly about the company since its collapse, “but there are other problems to solve that would be more rewarding.”

What, then, shall we say in closing about Magnetic Scrolls?

For all their indulgent talk about interactive fiction as a literary medium, Magnetic Scrolls was always populated first and foremost by technologists, with technologists’ priorities. Apart from Corruption — perhaps not coincidentally one of their very worst games in design terms — everything they produced hewed to tried-and-true templates, evincing little of the restless eclecticism that always marked Infocom. The innovations found in Magnetic Scrolls’s games were rather technical innovations, and ones that perhaps too often added little to the games that contained them. Because it was cool and fun to implement from a programming point of view, they built an elaborate system of weights, sizes, and strengths into their games from the beginning, even though nothing in their game designs actually required or even acknowledged the existence of such a thing. Similarly, they made a parser capable of understanding lengthy, tangled constructions that no player in the wild was ever likely to type, while forgetting to implement many of the shorter phrases that they were. It’s easy enough to see Magnetic Windows and the interface built using it as the ultimate — and ultimately fatal — manifestations of this tendency. Like FTL Games, another heavily technology-driven developer, their endless tinkering with their tools paralyzed them, kept them from finishing the actual games that were their real mission as a company.

For Magnetic Scrolls, however, the case is a little more complicated than merely that of a factory which got too focused on the component widgets at the expense of the finished product. Even had they managed to find a publisher and release the very worthy Wonderland one or one and a half years earlier as a simple illustrated text adventure, it was hardly likely to have been a success. The fact is that there was no good solution to the problem Magnetic Scrolls found themselves facing as the 1980s expired: the problem of the imploded commercial appeal of text adventures, the only sorts of games they had ever made and the only ones they really knew how to make. Faced with a marketplace that simply wasn’t buying many text adventures anymore, what was a text-adventure developer to do? Short of a complete reinvention as a maker of point-and-click graphical adventures or games in some other genre entirely — a reinvention the company did try to undertake with The Legacy, but far too late — Magnetic Scrolls’s fate feels inevitable, regardless of the details of the individual decisions that may have slowed or hastened their demise. Meanwhile the luridly anonymous, very un-Magnetic Scrolls The Legacy shows where a more comprehensive reinvention must have led them. Was it worth sacrificing their identity to save their company?

The marketplace forces that seemed almost to actively conspire against Magnetic Scrolls’s success almost as soon as they really got going has led, understandably enough, to no small bitterness on the part of the company’s principals. Already in Magnetic Scrolls’s twilight period, Anita Sinclair became known at conferences and trade shows for her rants about the alleged infantilization of computer games, about how the latest releases all assumed that players couldn’t or wouldn’t read. “When I was in the industry we were pioneers, paving the way for the future,” she said much later in 2001. “People [today] are aiming their games at younger and less sophisticated audiences. Today’s developers are writing in their minds to ten- to twelve-year-olds.”

Similar sentiments have been expressed by other former text-adventure developers, as well as by developers of the graphical adventures that did so much to kill text adventures, only to suffer a commercial collapse of their own that was almost as horrendous by the end of the 1990s. Easy and self-justifying though this line of argument is, there’s doubtless some truth to be found therein. Yet it can lead one to a dangerously incomplete conclusion in that it ignores the design sins that led so many of even the older and more sophisticated players Sinclair preferred to court to give up on the genre. Certainly Magnetic Scrolls’s own design record is decidedly spotty. It’s not hard to imagine a player encountering some of the cruelest, most unfair parts of The Pawn, Jinxter, or Corruption and saying, “I’m never playing a game like this again.” Magnetic Scrolls thought they could become “the British Infocom” by matching or exceeding Infocom technically, a task which alone among their peers they accomplished in many areas. What they failed to match — failed to even try to match — was Infocom’s attention to the non-technical details of game design, their rigorous process for taking a game from idea to polished final product.

And yet, lest we be too hard on them, the fact does remain that three of the six games Magnetic Scrolls produced (or six and a half if you count the freebie mini-adventure Myth) are actually good, perfectly recommendable old-school adventure games despite it all, giving the company an overall success-to-failure ratio matched by no other text-adventure maker not named Infocom. So, clearly they were doing something right despite it all. If they never quite succeeded in their ambition of becoming the British Infocom, they did succeed in becoming the next best thing: first among the field of also-rans. And, hey, a silver medal is an achievement in its own right, isn’t it?

(Sources: The One of July 1990; Zero of February 1990, March 1990, and October 1990; Games Machine of February 1990; Computer Gaming World of January 1991; Aktueller Software Markt of June/July 1989; Amstrad Action of July 1989; Computer and Video Games of December 1989; Crash of February 1990; CU Amiga of July 1990; PC Player of September 1993; PC Zone of September 2001; Compute! of January 1993; Sinclair User of December 1986. And of course see Stefan Meier’s Magnetic Scrolls Memorial for a trove of information on the games of Magnetic Scrolls and the company’s history.

As a final tribute to Magnetic Scrolls’s achievements, I do highly encourage any text-adventure fans among you who haven’t played Wonderland to give it a try sometime. You don’t even need to fiddle about with emulators, unless you just want to see the Magnetic Windows-driven interface in action in all its impressive if slightly unwieldy glory. The game is perfectly playable as an ordinary text adventure, played through the standard Magnetic interpreter for Magnetic Scrolls games, which is available, along with Wonderland itself, from Stefan Meier’s Magnetic Scrolls Memorial. For that matter, you can even now play Wonderland, along with all of the other Magnetic Scrolls games, online in your browser.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | The one puzzle that can perhaps be deemed questionable requires you to manipulate Alice’s own body in a way that will only yield an error message from just about every other text adventure ever made. So, know ye, prospective players, that Wonderland allows you to close and open Alice’s left and right eyes individually. |

|---|