Born in Cambridge, England, in 1952, Douglas Adams received a good public boarding-school education at Brentwood School before entering Cambridge University to read English in 1971. His dream, however, was not to become a scholar but to write and — and this is often overlooked — perform comedy like his hero, another ludicrously tall and ungainly-looking British comic named John Cleese. Thus Cambridge was attractive not so much because it was one of the two most storied universities in Britain but because it was the home of the almost equally legendary Footlights theatrical troupe, incubator of Cleese and the rest of his mates in Monty Python and, indeed, a whole generation of British comedy. Adams was eventually accepted by the Footlights, but came gradually over the course of several years to the disheartening realization that he was no John Cleese. He just wasn’t much good as a performer. His stage presence was awkward when not nonexistent, and he could never seem to suppress his big, goofy, good-natured laugh, which was literally infectious; it would suddenly ring out in the middle of a sketch, then quickly spread to his fellow players and derail the entire performance. His career in comedy, if he was to have one, would have to be made off the stage.

Adams, whose social gifts are legendary, managed to make the acquaintance of most of the members of Monty Python while still a starving student. After graduating in 1974, he did some writing for the truncated final season of Monty Python’s Flying Circus, and also had a couple of onscreen cameos that mark his swansong as a performer. Otherwise, however, his mid-1970s were largely a period of disappointment: an aborted television special that was to feature Ringo Starr (meeting whom must at least have been a huge thrill for Adams the rabid Beatles fan); various other failed or stillborn television specials and pilots; various disappointing stage revues. He was about ready to give it up, move to Hong Kong, and become, of all things, a ship broker, when BBC radio bit on his proposal for a science-fiction comedy serial called The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. The first of its six half-hour episodes, named by Adams “Fits” in homage to Lewis Carroll’s “The Hunting of the Snark,” premiered on March 8, 1978, with no promotion and in a truly horrid time slot: 10:30 PM on a Wednesday night.

Predictably enough, it pulled a 0.0 in audience share, which would seem to indicate that absolutely no one heard it and that it was destined for the same fate as all of Adams’s previous projects. But the rounding error in that figure was apparently a very vocal lot. Entirely due to word of mouth, ratings increased steadily with each additional episode, prompting the BBC to rerun the entire thing to yet better ratings just two weeks after “Fit the Sixth” concluded the serial. Hitchhiker’s was on its way to becoming a full-fledged phenomenon. Ironically, it happened just as Adams also sold a television script to Doctor Who (“The Pirate Planet”) and took the position of script editor for the series. Suddenly he went from knocking on doors to the heart of the BBC machine, with more work than he could handle; he lasted just a year with Doctor Who before it became clear that the smart move was to ride this Hitchhiker’s thing as far as it could take him.

And that, of course, turned out to be very far indeed. Although conceived before the film’s debut, Hitchhiker’s had the good fortune to premiere just after Star Wars made Britain, like the rest of the Western world, wild for anything science fiction. Adams soon found himself sitting at the nexus of an entire cottage industry, as Hitchhiker’s was adapted into seemingly every medium imaginable: novels (three of them in the initial rush); another six-episode radio serial; another audio version released as two double albums; a six-episode television serial; even theatrical performances. Adams was intimately involved with all of these variations and re-packagings, with the exception only of the plays.

It was, to say the least, a heady time in the life of the still very young Douglas Adams. His first Hitchhiker’s novel was published in October of 1979 and within a few weeks was the bestselling paperback in Britain. Suddenly he was a wealthy and even modestly famous man. He later colorfully described this period as “like having an orgasm with no foreplay.” It was even stranger because the role in which he would enjoy his biggest success, that of novelist, had never been anywhere on his career agenda, a fact which perhaps does a great deal to explain why he would struggle so mightily to actually, you know, write books in the years to follow. Initially a strictly British phenomenon, Hitchhiker’s spread to the United States as well within a year or two, when the books were picked up by Simon and Schuster’s Pocket imprint and PBS broadcast the television version. By 1982, when the third book debuted a bestseller, Hitchhiker’s was firmly ensconced as an institution in nerd culture on both sides of the Atlantic, a place it still occupies to this day. And it looked to have the potential of spreading well beyond the nerds: immediately after finishing the third book, Adams moved to Hollywood to begin working on the script for a Hitchhiker’s feature film to be produced by Ivan Reitman of Animal House fame.

Hitchhiker’s wasn’t the only novelty in nerd culture of the early 1980s. There was also the computer, and computer games. These two things inevitably came together quite early. In 1981, a British civil servant named Bob Chappell decided he’d like to write a text adventure based on Hitchhiker’s for his Commodore PET. He wrote to Adams’s British publisher, Pan Books, to ask permission. With little idea just what he was really on about, they said sure, as long as Pan and Adams himself were properly acknowledged. Chappell made his game, a simple treasure hunt which demanded you return five items to the “Five Artefacts Inn” to win; the parser which did the demanding was “Eddie, your faithful computer” from the novels. Chappell sold the game to software publisher Supersoft for “£500 worth of microchips and assorted programs.” However, the British software market was still in its infancy and the market for PET games — the PET being a fairly expensive machine used primarily for business — was a pretty small part of even that. Thus this original version of Hitchhiker’s made little impression, and seems never to have even been noticed by Adams himself or any of his immediate associates.

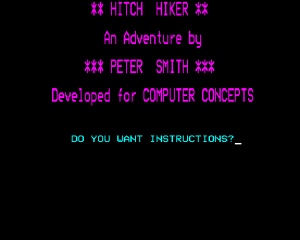

“Hitchhiker’s” on the BBC Micro

“Hitchhiker’s” on the Spectrum

Eighteen months later, the situation had changed dramatically. Not only was Hitchhiker’s more of a phenomenon than ever, but computer use was also exploding in Britain, with Clive Sinclair the toast of the nation. Supersoft decided to give the game another belated push, in new versions for the Commodore 64, Commodore VIC-20, and Dragon 32. Meanwhile, thanks to the original having been written in easy-to-modify BASIC, clones and variations were starting to pop up on other platforms. At least two companies attempted to sell their own versions: Computer Concepts made one for the BBC Micro, while Estuary Software Products made one for the Speccy and the Apple II.

Those completely unauthorized knockoffs, infringing as they did both on the intellectual property of Supersoft and that of Adams, were easy enough to head off. But the situation with the Supersoft version, thanks to that damned letter from Pan Books, was more complicated. It was pretty obvious to everyone in Adams’s camp that a computer game based on Hitchhiker’s was a natural, what with the demographic intersections at play between computer gamers and Hitchhiker’s fans, but the decision had been made to make any such project a tie-in to the big movie version of the story, for which Reitman and Columbia Pictures had just paid £200,000 and which everyone hoped might be released as early as 1984. “A legal storm is brewing,” announced the British weekly Popular Computing with gleeful anticipation in their April 21, 1983, issue. Sonny Mehta of Pan Books, the people who had created this mess in the first place, said they were “very concerned” about the game. Peter Calver of Supersoft insisted that they had all the permission they needed in that two-year-old letter.

As these things so often do, it all blew over rather anticlimactically. Within two weeks of pronouncing their defiance, Supersoft, apparently deciding it was best not to tangle legally with several companies hundreds or thousands of times bigger than they were, settled out of court, and agreed to remove all Hitchhiker’s references from the game. The game was renamed Cosmic Capers. “Milliways, the Restaurant at the End of the Universe” became “Colonel McWimpays, the Fastest Restaurant in the Galaxy”; “Vogons” became “Verrucans”; the “Ravenous Bugblatter Beast of Traal” became the “Barbaric Binge Beast of Bongo”; the “Pan-Galactic Gargle Blaster” became the “Burgunzian Shazam Shandy”; etc., etc. It wasn’t a particularly good game with or without the Hitchhiker’s license, and sank at last without leaving much of a trace. But still the game of Whack-a-Mole continued. Fantasy Software soon released a very thinly veiled Hitchhiker’s knock-off for the Spectrum called The Backpacker’s Guide to the Universe which at least had the virtue of being an original piece of code. Once again Adams’s lawyers sprung into action, and Fantasy was forced to re-release it as simply Backpacker and take out a series of advertisements in magazines saying that “Backpacker is in no way connected with the works of Douglas Adams.”

Douglas Adams was paying much more attention as all of this went down for the very good reason that he had himself become an avid computer user in the time since Pan had sent Chappell that troublesome letter. He had been a bit of a gadget freak since his photography classes back at Brentwood, where he found himself fascinated not so much with the art of photography as with the technology — the cameras themselves. Now that he could afford it, he filled his home with cameras, guitars (Adams was something of a frustrated would-be rock star who delighted in palling around with Pink Floyd, Dire Straits, and Paul McCartney’s band), and, of course, cars (he bought his first Porsche with the advance for the first Hitchhiker’s novel and just kept going from there). Computers, when he discovered them, were a natural progression. As with Michael Crichton, another author turned computer enthusiast, his first tentative steps came in the form of a standalone word processor. He’d soon replaced it with a real computer, a DEC Rainbow. Many, many more would follow. More so than even Crichton, for whom hacking was apparently something of a passing phase, Adams would remain a noted computer enthusiast and popularizer for the rest of his life.

Which brings us to Infocom. The story of how Douglas Adams ended up working with them is still somewhat murky. What follows is my best reconstruction of events from the many and occasionally contradictory available sources.

Adams discovered Infocom very soon after he discovered computers. He ended up buying several of their games, developing a particular fascination with Mike Berlyn’s Suspended. He found them a great aid to “not writing” during days in his study; not, as Infocom would soon learn, that he needed much help in that area. One day on a press junket of some sort or another he started discussing computer games with an executive from his American publisher, Simon & Schuster. He said he was rather nonplussed as a whole with what he’d seen, with the exception of this one company, Infocom. Without saying anything more about it to Adams himself, the executive interpreted Adams’s admiration to indicate that he would likely be willing to make a computer version of Hitchhiker’s in partnership with them.

Soon after, Simon & Schuster began to reach out to Infocom with an eye to possibly acquiring them. Whether there is, to borrow from the eventual Infocom Hitchhiker’s game, any causal relationship between these two events is not clear to me; Infocom may already have been on Simon & Schuster’s agenda. What is clear, however, is that Simon & Schuster took Adams’s alleged interest to Infocom when they did reach out, adding the Hitchhiker’s franchise to Star Trek on the list of things they could do for them. It was a tempting proposition indeed. In Mike Dornbrook’s words: “We were interested in both of these things, and we actually had a fairly intense internal debate because we didn’t think we could do both at once.” Then word reached Adams through the grapevine that Simon & Schuster was “dangling him like a carrot” before Infocom. A very unhappy Adams let Simon & Schuster know in no uncertain terms that there was a big gap between an expression of admiration for someone and a proposal of marriage. Adams being the cash cow he was, Simon & Schuster had to keep him happy. They thus had no choice but to go back to Infocom and sheepishly say that, well, the Hitchhiker’s thing might not be such a done deal after all. But hey, there was still Star Trek! The dance between the two companies then continued for many more months.

But Adams was actually not hostile at all to the idea of working with Infocom. He just didn’t like the way that Simon & Schuster had handled it. In fact, there was no legal reason that Simon & Schuster need be involved at all. Yes, they were Adams’s American publisher, but the franchise itself belonged to him, as evidenced by the fact that he had been able to sell the movie rights to Columbia rather than Paramount, who shared with Simon & Schuster the parent company of Gulf and Western. Speaking of that movie: it was starting to look like it wasn’t going to happen anytime soon. Douglas Adams the scriptwriter had proven underwhelming to Reitman and his colleagues. They said his script was too long, and wasn’t structured the way a three-act commercial blockbuster needed to be. Adams was digging in his heels on the requested changes, and, worst of all, Reitman and Adams mixed like oil and water — or a commercially-oriented Hollywood producer and a quirky British humorist. About the only qualities the two men seemed to share when together in a conference room were stubbornness and arrogance. And then there was Adams’s legendary gift for procrastination. As 1983 ground on and the script failed to progress, Reitman grew more and more infatuated with another far-out comedy that had crossed his desk, a little thing called Ghostbusters which was written by Dan Aykroyd, a Hollywood pro he knew how to deal with. By that autumn he had put Hitchhiker’s on the shelf, where it would linger for many years, much to Adams’s chagrin, to proceed full speed ahead with Ghostbusters. Adams returned to Britain a frustrated man, having just experienced his first real failure since selling that first Hitchhiker’s radio serial. With no need to wait for the movie to make a computer-game version, perhaps an Infocom Hitchhiker’s could serve as something of a consolation prize. After all, apart from film computer games represented about the only medium the franchise had not yet conquered (unauthorized or semi-authorized knockoffs excepted, of course).

Ed Victor, Adams’s agent, therefore contacted Infocom’s Mike Dornbrook through a mutual acquaintance, Christopher Cerf of the Children’s Television Workshop, a fellow who was clearly very interested in interactivity and shows it by continuing to show up as a supporting player to so many of the little dramas I write about in this blog. Dornbrook and Victor hammered out an agreement over the course of several meetings, with only limited input from Adams, who in the words of Dornbrook “would often be at the meetings, but would certainly defer to Ed on any business-related decisions.” Still, a creative problem soon surfaced that, much to Dornbrook’s chagrin, threatened to derail negotiations.

Douglas wanted to work with Marc [Blank] or Mike [Berlyn]. He was dead set on them, because they had written the games that he liked. He really liked Suspended, really wanted to work with Mike Berlyn. Mike Berlyn wanted nothing to do with a collaboration. I was saying, “Oh, my God! We’ve got Douglas Adams desperately wanting to write a game with us! He wants to do Hitchhiker’s with us! There’s no question whether this will be a success!” Who wouldn’t want to work with this incredibly creative guy? But no one wanted to do it.

Just glancing at their relative sales and statures as writers, it does indeed seem incredible that Berlyn would turn down such a career-making opportunity. But these were heady times at Infocom, which prompted many of the still young men who worked there to have a somewhat, shall we say, exaggerated sense of themselves. With the lukewarm, sour-atmosphered Infidel as evidence of the work Mike Berlyn did when pushed into a project he wasn’t enthusiastic about, Dornbrook knew he needed to a) find a new partner for Adams (which was more difficult than it ought to be; Berlyn’s wasn’t the only big ego in the place); and b) sell Adams on whichever Imp he could convince (also no trivial task, given that Adams was another guy flush with commercial success and critical praise who liked things his own way).

At the time, Steve Meretzky was just finishing up Sorcerer. For a next project, Infocom had planned to partner him with science-fiction writer Joe Haldemann on an adaptation of the latter’s 1977 novel All My Sins Remembered. With Haldemann spending a year as a visiting professor at nearby MIT, it seemed the perfect window of opportunity for what would have been Infocom’s first full-on foray into bookware. But Haldemann didn’t seem as enthusiastic as his agent had been, and the project stalled after one or two phone conversations between the two. With Meretzky thus left without an obvious next project, and with the Haldemann project as evidence that he — steady, reliable fellow that he was — would be willing to work as inevitable second fiddle to a name author where the other Imps weren’t, he was the obvious choice. And of course his first game, Planetfall, had been more than a little similar to Hitchhiker’s.

Indeed, Planetfall is so similar to Hitchhiker’s in tone as well as subject matter that most still assume it to have been an homage to Adams’s work from the start. In fact, however, Meretzky had not been aware of Hitchhiker’s at all when writing the game. It was the testers who first told him that, you know, this really feels like something by this guy named Douglas Adams. This prompted him to borrow cassettes of the original series from a friend. He loved them — loved them so much that he added a little tribute in the game, in the form of a towel with “Escape Pod #42” and “Don’t Panic!” stenciled on. That was perhaps a bad move in the long run, because it left many people with the impression that Meretzky had been aping Adams from the start, when it really was just a matter of the proverbial great minds thinking alike. At any rate, as Infocom’s resident comedy-science-fiction Imp Meretzky would seem to have been the natural choice for a partner for Adams from the start. Yet it actually took all of Dornbrook’s charm to sell him on the idea; Adams was apparently entirely unaware of Planetfall, or had dismissed it as yet another cheap knock-off of his work.

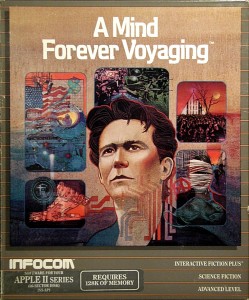

Once Adams agreed to Meretzky, the contract was quickly signed. It was quite an ambitious one. Adams and Infocom agreed to do not just one Hitchhiker’s game but six. Given the technical limitations under which Infocom labored, which limited every game to no more than a novella’s worth of total text, each game would cover half of one of the then-extant three Hitchhiker’s books. The deal was signed just as 1983 turned into 1984. The first game should be out in time for Christmas 1984, with another presumably following every year.

Technophile that he was, Adams was hugely excited by the project — probably more excited, in fact, than he was about writing a fourth Hitchhiker’s book, the contract for which he signed at about the same time. He was even briefly taken with the notion of learning ZIL and actually helping to program the game; Meretzky remembers Adams proudly pulling out a simple “3D Tic Tac Toe” game he had written in BASIC to show off his burgeoning programming chops at one of their first meetings. But given Adams’s schedule for the year — which included writing the aforementioned book as well as the game, while also needing to leave time for his many and varied social and recreational pursuits — cooler heads prevailed. In Meretzky’s words: “We’d do the design together, Douglas would write the most important text passages and I’d fill in around them, and I’d do the implementation, meaning the high-level programming using Infocom’s development system.” They would do most of the collaborating electronically using Dialcom, the world’s first commercial email provider, after they spent a week together in Cambridge to get things rolling.

Adams accordingly came to Infocom’s offices in February of 1984 to spend a week hammering out the basic structure of the game with Meretzky. He arrived with no fanfare whatsoever. Stu Galley:

I happened to be walking by the front door when he came in — unescorted, with no one there to welcome him. I had to ask who he was. When he told me, I said, “You probably want to go talk to Joel [Berez] or Marc.”

Looking beyond the obvious commercial attractions, Hitchhiker’s made a pretty great setting for a game. The Achilles heel of any novel-to-game adaptation is generally the plot, specifically the question of what to do when the player deviates from it. But, as Meretzky notes, Hitchhiker’s was more like a grab bag of “characters, locations, technologies, etc., while the story line wasn’t all that important.” Or even more flexibly, as Adams put it in a contemporary interview, “a set of approaches and attitudes, with a few rough ideas about characters.” At first, Meretzky admits that he was “awed” by Adams, while Adams was uncertain about interactivity and how to use it. Meretzky sees this as the explanation for the beginning of the game, which is very linear and quite slavishly follows the opening of the book. Later, however, after the player (as Arthur Dent) and Ford Prefect escape the Earth just as it is destroyed by the Vogons, the game blossoms into its own original, wildly nonlinear design, a reflection of Adams’s growing comfort with the medium and both men’s growing comfort with one another.

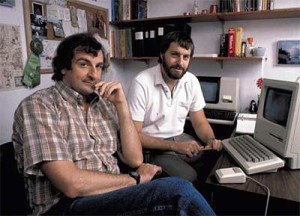

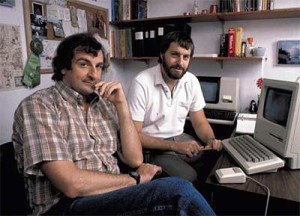

Douglas Adams and Steve Meretzky, February 1984, with the first Mac Adams ever saw

It was also at Infocom that February that Adams began a love affair that would continue for the rest of his life. As part of his tour around their offices, the Imps took him to the loft above the main floor where the Micro Group kept dozens and dozens of different computers, practically a showroom of all of the significant — and most of the insignificant — microcomputers that were now being or in the recent past had been manufactured. The crown jewel of the collection was a pre-release version of the Apple Macintosh, sent by Apple so that Infocom could have their games on the new machine as quickly as possible. Adams was immediately entranced. He promptly went out to buy one for himself, to take back to Britain with him. He claimed until the end of his life, quite possibly rightly, that this machine was the first Macintosh ever to make it to British soil. By 1985, when he was profiled in MacWorld magazine and thus first began to become known as a zealot for this platform so known for zealotry, he owned three; by 1987, six. The passion never faded. Right up until his death in 2001 he could be found waxing lyrical on the Internet about his collection. By then he required an entire room just to store all his obsolete models. As for the latest models: he “just wanted to hug” them every time he turned them on, just like in the old days. Macs do strange things to some people. Having never caught the bug myself, I’ll say no more, but just get back to 1984.

As everyone at Infocom would learn all too well before the company wound up, counting on Adams to deliver anything on time — or at all, for that matter — was usually a fool’s game. It was typical of him to start a project with huge enthusiasm; thus things went pretty swimmingly over that first week in Cambridge. But once Adams returned to Britain Meretzky found it harder and harder to get any work out of him. He wasn’t the only one: Adams was supposed to be working on that fourth Hitchhiker’s book, also to be in stores in time for Christmas, and had yet to even begin. His various handlers encouraged him to get away from the distractions of a London chock full of far too many shiny objects. So he packed his Saab with books, files, and computers and checked into Huntsham Court, a tiny hotel in Devon. It didn’t help much. In ten weeks there he wrote not a page of the would-be book, although he did develop a new hobby of comparative champagne-shopping and generally enjoyed himself immensely.

In many ways the game was looking quite promising, but there were still huge gaps in the design to be filled. Infocom finally decided to get more confrontational — usually the only way to get any work at all out of Adams after his first blush of enthusiasm for any given thing had faded. In May, shortly after Adams had ensconced himself in his remarkably unproductive writer’s retreat, they sent Meretzky over to join him there for four days, under orders to finish the design at all costs. With the game needing to ship by October to join the Christmas rush and heaps of coding and testing needed before that could happen, it was either that, let Meretzky finish it alone (a bad move politically, especially considering that Infocom hoped to get five more games out of Adams after this one), or postpone it — which would likely mean cancellation in the long run, as it was unlikely that Adams would get any more interested in the future.

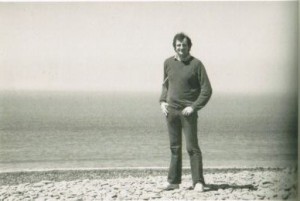

Douglas Adams on the beach at Exmoor National Park in May 1984, where he and Steve Meretzky finished the Hitchhiker’s design

Meretzky in person proved to have just the right touch; he managed to keep Adams “pretty focused” on the game despite also allowing time for some sightseeing and for enjoying the “opulent cuisine” of Huntsham Court. The two came up with the final puzzle on the last day of the visit on the beach at Exmoor National Park. Then Adams returned to not writing his book, while Meretzky jetted back to the United States for three more weeks of feverish implementing. By July the game was in the hands of the first testers in roughly complete form. In September Adams dropped by Infocom’s offices to work out answers to some final questions raised by the testing process, and that was that.

Until now we’ve been seeing Adams at his most exasperating. Certainly it’s true that he didn’t have to work that terribly hard to earn his co-authorship credit alongside Meretzky; at least 90% of the actual work that went into the game was the latter’s. Meretzky not only did all the programming but also wrote at least as much of the text as Adams. The latter mostly provided just the text for the direct path through the game, leaving Meretzky to deal with all of the side trips and the incorrect and crazy things the player might try as well as any of the boring bridging passages that Adams couldn’t be bothered about. For all the superficial similarities in their humor, the two men’s working habits could hardly have been more different. Meretzky was disciplined, organized, methodical, seemingly immune to writer’s block and artistic angst, a dream employee for any manager of creative types. Adams was… well, Adams was Adams. Suffice to say that the spaceship captain in The Restaurant at the End of the Universe who just can’t seem to will himself out of his bathtub for years at a stretch was based on Adams himself. Although he is unfailingly diplomatic when describing the experience today, Meretzky must have suffered greatly at being saddled to such a temperament. Yet it’s also true, as Meretzky freely admits, that that unique Douglas Adams sensibility was essential to making the game the off-kilter, vaguely subversive creation it became. Who else on the planet would have thought to make “no tea” and “a splitting headache” an inventory object? Who would have thought to make the game lie to you? Who would have thought to make the player’s random typo from dozens of moves ago an integral part of the story? Adams pushed Meretzky to, as Mike Dornbrook puts it, “break the rules” that he’d thought were inviolate.

If Infocom thought they’d had it bad working with Adams, they could rest assured that the book had proven to be an even more nerve-wracking project. Upon Adams’s return to London late that summer with exactly no progress to show for his ten-week writer’s retreat, a desperate Sonny Mehta of Pan Books moved into a hotel suite with him for two weeks, during which he literally stood over him and forced him to write the book. Thanks to a subsequent mad scramble by both his British and American publishers it arrived in stores slightly ahead of the game. Unsurprisingly given its gestation, So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish is both shorter than and in most people’s opinion worse than its three predecessors. But as for myself: as I wrote in my previous article, I find the book a refreshing change from its predecessors. Go figure.

Having seen Adams at his worst, if not quite his truly infuriating worst, Infocom would now get the opportunity to see him at his best, to learn why so many people adored the guy even as he continually made their lives hell by not doing what he promised to do. Shortly after Adams’s last visit to Infocom that September, Marc Blank and Mike Dornbrook flew to London to plan the game’s promotional strategy. They had over a week there, which they expected to be largely filled with waiting for a few productive meetings with Adams and his people. They didn’t know Adams that well. He loved nothing better than to play the host and entertainer, and with book and game now both complete he could do so without guilt. He and his girlfriend (later wife) Jane Belson filled “almost every waking hour” the pair spent in London, and charmed the hell out of them in the process. Dornbrook:

We’d drive past a building and he would start telling a story. Now, he knew a lot about English history — but the thing was, Jane knew a lot more! Douglas tended to know the commonly accepted story, but she would know what the latest interpretation of that was. Just driving around the city and hearing all this history, and in a very classy, intellectual way, arguing over the history — it was just amazing.

But most amazing of all were the evenings. On his own Adams was already “probably the most interesting dinner companion you could have,” one of the great raconteurs of his time. Despite his reputation as a funnyman, he wasn’t a joke-a-minute kind of guy at all. What he was was deeply interested in and knowledgeable about all sorts of topics, from the universal to the esoteric, with lots of interesting thoughts of his own but also with a willingness to truly listen to and consider those of others. And then there was his guest list. Adams had taken advantage of the fame and fortune Hitchhiker’s had brought him to make the acquaintance of a dizzying cross-section of cultural, technical, and scientific movers and shakers: names like Alan Kay, Salman Rushdie, Bill Gates, David Gilmour. Evenings in Adams’s drawing room were like evenings spent in a classic Paris salon, or, as Mike Dornbrook put it, a visit to a Hollywood movie of the 1930s: “sparkling conversation by very interesting people talking about interesting subjects,” with wine to die for.

One evening Blank and Dornbrook found themselves breaking bread with Alan Coren (editor of Punch magazine), Terry Jones (of Monty Python), and Clive Sinclair in addition to Douglas and Jane. That dinner party, still remembered by Dornbrook as one of the most amazing evenings of his life, would also make its way into the British tabloid press. Adams had just that day received from Pan Books the very first copy of So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish. The press, for whom Sinclair could still pretty much do no wrong at this stage, would later report that Uncle Clive had insisted that he be allowed to buy it for a huge donation to charity. That account wasn’t precisely wrong, but the details were perhaps a bit more grubby than it might imply.

Adams was proudly showing the book to his guests when Sinclair, who was possessed of loads of imperiousness but very little social empathy, announced that he would like to have the book, to give to his son for his birthday. Adams, rather taken aback, said that he’d be happy to get another copy to him tomorrow, but this one was quite special to him, etc. Whereupon Sinclair offered “£1000 to the charity of your choice!” On the spot and very aware, as always, of his duties as host, Adams cheekily said fine, his choice would be Greenpeace — just about the last charity in the world to which Sinclair, arch-Tory and bosom buddy of Margaret Thatcher, would happily give money. But Sinclair agreed, and poor Adams saw his precious heirloom vanish into Sir Clive’s satchel.

Later in the evening Sinclair tangled with the less accommodating Marc Blank on one of those topics guaranteed to ruffle feathers in any mixed company: evolution. When Sinclair declared that natural selection was not sufficient to explain everything, Blank told him, at first politely but then increasingly less so, that he didn’t understand what he was talking about, and that he, Blank, with a degree in biology and training as a medical doctor, was better qualified to judge. The argument raged for the rest of the evening, while Douglas and Jane fruitlessly tried to change the subject. Later, Blank and Sinclair shared a cab ride home, with poor Dornbrook sitting uncomfortably between them in the “stony silence.” The two would never meet or speak again.

It’s possible that this argument may have had far-reaching consequences for Adams himself. He may have played the tolerant host at that dinner party, but he listened to the conversation keenly. Later in his life, after he became friends with Richard Dawkins, he himself became a noted (not to say strident) advocate for evolution. His biographer M.J. Simpson speculates that his interest in the topic may date from this evening. If so, two of the defining obsessions of Adams’s later life — his advocacy for evolution and his advocacy for the Macintosh — stem from his relatively few direct interactions with Infocom. (Which is not, of course, to say that he wouldn’t have discovered his interest in either by some other medium had he never come into contact with the Imps at all.)

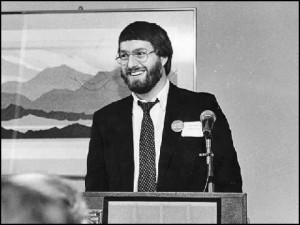

Steve Meretzky introduces the Infocom Hitchhiker’s to a packed room inside Rockefeller Center

Poor Steve Meretzky, the one who had done most of the actual work on the Hitchhiker’s game, didn’t get to experience the Douglas Adams Salon. He was back in Cambridge at the time, swatting the final bugs and prepping the game for release. At least he got a pretty nice consolation prize. Late in October, Adams came over to begin a publicity junket to promote his new book and game. It kicked off with a joint press conference with Meretzky and Infocom at Rockefeller Center, done just like the big boys in entertainment did it. The usual computer-trade-press suspects were almost lost amidst all of the mainstream-media reporters from places like The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, and even Playboy. Meretzky, barely two years removed from a career as a construction manager, got to stand at the podium in suit and “Don’t Panic!” button and trade jokes and repartee with Douglas Adams while the flash bulbs went off around them. (“I want you to know that I really enjoyed working on this game,” said Adams, “and I’m not just saying that because I’m trying to sell it. That’s only 90% of the reason.”) They were a good match physically as well as creatively; at 6’4″, Meretzky was about the only person from Infocom who could stand next to the 6’5″ Adams without looking like a dwarf. After the press conference the two jetted off to charm press and customers at the Las Vegas Comdex show and in Silicon Valley. Meretzky found it all very exciting, but found Adams’s now long-established press-conference schtick rather exhausting in time; he told the biscuit story from So Long using the exact same words at virtually every stop. He even told it during his somewhat awkward appearance on Late Night with David Letterman; Dave clearly had no real idea what Hitchhiker’s was, and a clearly nervous Adams rather flubbed the punch line. On the bright side, Infocom did at least get the most cursory of plugs on national television, when Letterman, rattling off the standard canned spiel about extant Hitchhiker’s incarnations, mentioned that it was now “even computer software.”

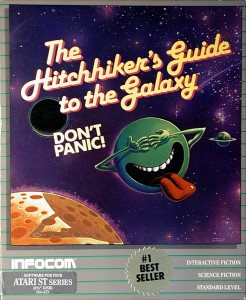

For Infocom, whose corporate rise had been almost as meteoric as Meretzky’s personal rise, this was truly the top of the mountain. Even as Hitchhiker’s soared to the top of the bestseller charts they were being wined and dined by Richard E. Snyder of Simon & Schuster in his private boardroom. Just a week after the Hitchhiker’s shindig in Rockefeller Center they hosted their second (and, as it would turn out, final) big press conference there, to announce their forthcoming database manager Cornerstone. Their booth at that Comdex, where they passed out thousands of free “Don’t Panic!” buttons to all and sundry, was amongst the most frequented and discussed at the show. They got their name onto National Public Radio stations around the country when they sponsored the first Stateside airing in years of the original Hitchhiker’s radio serials. They had truly arrived, and on multiple fronts at that.

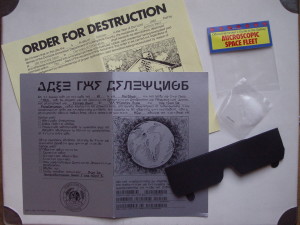

Mike Berlyn clowning around on the Infocom assembly line, November 1984

The Hitchhiker’s game itself was the biggest hit Infocom had ever had, just as Dornbrook had known it would be. They literally couldn’t make them fast enough to meet demand that Christmas. As Meretzky himself recounted in an article for The New Zork Times, Infocom had to take desperate measures. They leased some more warehouse space just to have someplace to put the avalanche of feelies, boxes, manuals, and diskettes coming in for assembly. Ernie Brogmus, Infocom’s production manager, came to Meretzky to ask if he could organize some help from his white-collar colleagues inside the Wheeler Street offices. That evening Meretzky put a sign-up form on the office billboard for twenty volunteers to come to the assembly plant for a seven-hour shift that Sunday. When he arrived in the office next morning at 9:30 there were thirty-five names on it. Forty people actually showed up. Soon Infocom organized a Saturday shift as well as evening shifts: “They were turning up with husbands and wives and mothers and sisters and brothers and friends.” Thanks to such dedication and camaraderie, Infocom in November of 1984 shipped more product than in any month before or after: 62,000 games, 6000 promotional “Sampler Packs,” and 21,000 InvisiClues hint books.

Hithchhiker’s went on to sell almost 300,000 units, over 200,000 of them in its first year, to become Infocom’s all-time second biggest seller, behind only Zork I, the game that had gotten it all started. Reviews were uniformly stellar. About the only grumbling came from some of Adams’s original British fans, who complained at his decision to work with an American company and at the fact that the game was never made available for the biggest home computer in Britain, the Sinclair Spectrum. “He’s putting the boot into his own fans, the British computer industry, and for all he cares the country itself,” wrote one particularly exercised ex-fan in Popular Computing. In Adams and Infocom’s defense, Sinclair’s decision not to produce a disk drive for the Spectrum made it impractical to port Infocom games to the platform. Publishers like Level 9 serving the thriving British adventure market were also a bit stung by the rejection, but to their credit largely seem to have taken it as motivation to improve rather than grounds for sulking.

Hitchhiker’s is not only of huge commercial and historical importance to Infocom and the adventure game; it’s also of huge artistic interest, with sections that almost feel like a deconstruction of the traditional text adventure. Accordingly, and having now given you the historic and commercial context, I think we should look at the game itself in some detail. Besides, it’s a fun one to write about, full of bits just screaming out for annotation. So, we’ll make that the next item on the agenda.

(The most detailed history of Adams’s relationship with Infocom from his standpoint is found in M.J. Simpson’s biography Hitchhiker. For the perspective from within Infocom, Jason Scott’s Get Lamp materials were, as usual, key. Also very useful were the April 1985 Compute!’s Gazette, the April/May 1985 Commodore Power Play, the April 1985 Electronic Games, the October 1982 Your Computer, and issues of Popular Computing from April 21, 1983; May 12, 1983; January 17, 1985; and March 28, 1985. And of course Infocom’s own New Zork Times newsletters from around the period. Oh, and thanks to Steve Meretzky for clearing up a question or two via email.)