Late in the fall of 1983, when it was clear that Ultima III was turning into a huge success and thus that their new company Origin Systems was going to be a viable operation, Robert Garriott came to his little brother Richard with a forlorn plea. Robert, you may remember, had for months been commuting via his private Cessna between the Garriotts’ family home in Houston, whose garage served as Origin’s development studio and assembly line, and North Andover, Massachusetts, where his wife Marcy worked for Bell Labs. It wasn’t, to say the least, an ideal way to run a marriage. Would Richard and the rest of the fledgling company agree to move to North Andover for three years? After that, Marcy expected a promotion that should make it much easier for her and Robert to move, and, assuming the company was still alive, they’d then move wherever Richard and the rest liked. Young, unattached, and ready for adventure as they were, just about everyone agreed. They packed their cars with their personal possessions and rented two trucks to fill with supplies, computers, and other equipment — most notably the precious shrink-wrap machine — and headed northeast just weeks later.

That winter was a bad one, with some of the worst storms of the decade. They hit major snow before they got out of Arkansas. Anyone who’s ever seen a Texan trying to drive on snow and ice can perhaps attest to what a miracle it was that they got to North Andover at all. Once there, the snow and bitter cold just continued for months. That first winter wasn’t the best introduction to the place that Richard still calls “the frozen wastes of New England.” He totaled his car on the icy streets within days; his house right next door to his brother Robert’s, which he rented with Chuck Bueche and Mary Fenton, was burglarized not once but twice, resulting in the loss of thousands of dollars worth of computers and home electronics; he and his buddies couldn’t seem to connect with any of the locals, who viewed their Texas accents and strange business of making computer games with suspicion. Things wouldn’t get much better; Richard in particular remained a hopeless fish out of water throughout his time in New England.

The only thing to do was to throw himself into life inside the Origin bubble. He made his own fun, instituting a daily five o’clock ritual called “Rubbaser war,” using $75 graphite-and-steel guns that could shoot rubber bands at speeds of up to 120 miles per hour; they hit with such force that the combatants had to wear helmets. He also continued to celebrate his favorite holiday with elaborate Halloween parties, even if the number of people around him eager to attend them had rather dwindled since the move. The moment when the locals decided once and for all that they wanted nothing to do with him may well have been the first of these: Richard, who was great at preparing for such big events but not so great at cleaning up after himself, left unnervingly realistic-looking bloody body parts strewn across his lawn through much of the following winter.

With Chuck Bueche’s action game Caverns of Callisto having failed to set the industry on fire, Origin now concentrated on, as their tagline would eventually have it, “creating worlds” in the form of big, ambitious games. Soon after the move to New England, they hired Dave Albert away from Penguin Software. Albert, who had majored in journalism at university and served as editor and writer for SoftSide magazine before coming to Penguin, would help Robert Garriott to put a professional face to this collection of young hackers. Albert also brought with him Greg Malone and his game in progress, the very original if polarizing oriental CRPG Moebius. Before releasing their next slate of games after Ultima III and Caverns of Callisto, Origin signed a distribution deal with Electronic Arts, becoming one of the first of what would eventually be quite a number of EA “Affiliated Labels.” This gave the still tiny Origin a badly needed presence in mass-market chains like Toys “R” Us and Sears.

Origin stretched out its tendrils in many intriguing directions during these early days. They entered into a contract with Steve Jackson Games — Steve Jackson was a friend of Richard’s from his Austin SCA troupe — to adapt that company’s popular board game Car Wars for the computer. They also agreed to make a computer game to accompany a planned film version of Morgan Llywelyn’s novel Lion of Ireland; Richard would get to spend two weeks on the set in southern Ireland soaking up the ambiance in the name of research. Richard also made tentative plans with none other than Andrew Greenberg of Wizardry fame to collaborate on “the ultimate fantasy role-playing game.” Most of this came to naught: the movie’s financing fell through and it never got made; the ultimate collaboration remained nothing more than talk. Only the Car Wars project survived, and only after a fashion: Chuck Bueche turned the turn-based board game into the real-time CRPG Autoduel over the considerable misgivings of Steve Jackson.

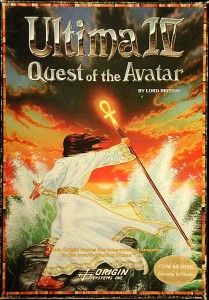

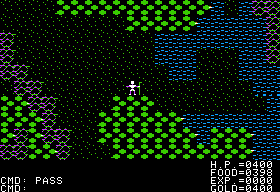

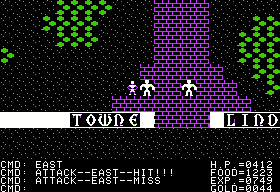

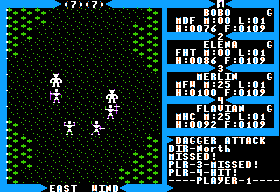

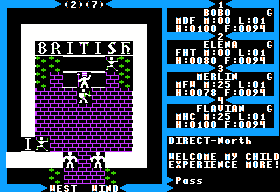

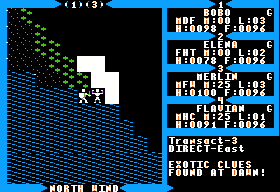

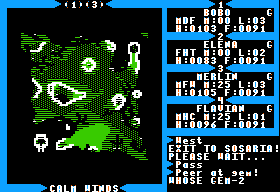

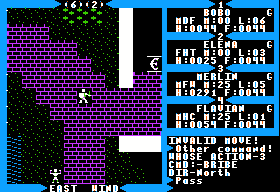

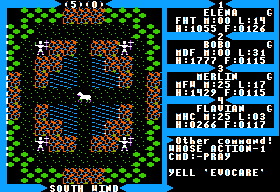

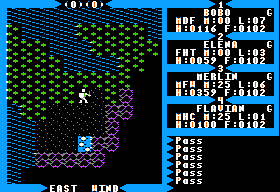

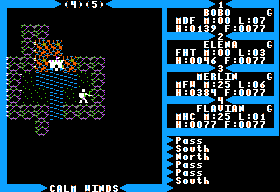

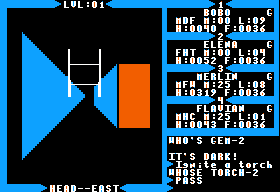

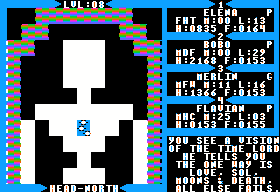

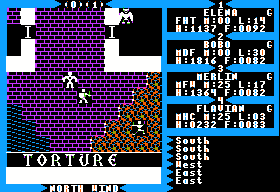

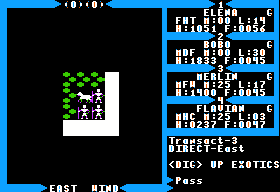

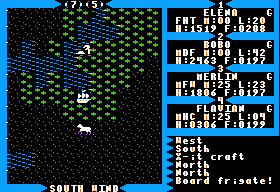

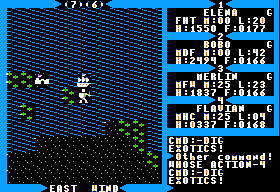

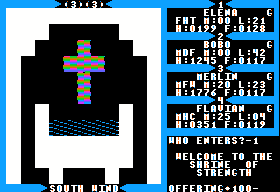

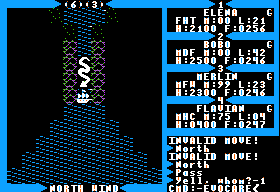

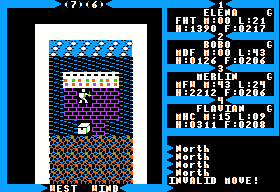

Meanwhile and preeminently, there was Ultima IV, the game that would change everything for Ultima and for Origin. As was his routine by now, Richard started working on it almost from the moment that Ultima III shipped, starting once again from the previous game’s code base and once again designing and coding virtually everything himself on his trusty Apple II. But, like the fourth Wizardry game that was its obvious competitor, it took much longer to complete than anyone had anticipated. Originally slated for Christmas 1984, it took a final desperate dash just to get it out in time for Christmas 1985.

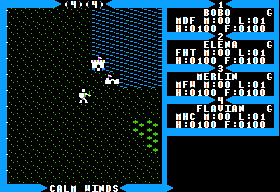

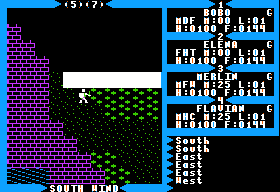

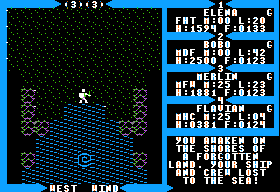

Anticipation grew all the while. For a game to remain in active, continuous development for two years at that time was virtually unprecedented. Truly Richard Garriott must be doing something amazing. The hints and tidbits that he let drop during interviews certainly sounded good: Ultima IV‘s world map would consist of 256 X 256 tiles, 16 times the size of Ultima III‘s 64 X 64-tile world; there would be a full parser-based conversation engine for talking with others; spells would now require reagents to cast, with the finding of their recipes and ingredients a mini-game within the game; dungeons would now contain “rooms” that opened into a tactical map. Yet the thing that Richard kept bringing up most was none of these incremental improvements, but something he insisted marked a change in the very nature of the game. There would be, he said, no evil character to defeat. Instead the player must become a better person, an “Avatar of Virtue.” What was that all about?

Richard Garriott has told many times the story of how Ultima IV came to be. Akalabeth, Ultima I, and Ultima II had, he says, existed for him in a vacuum — or, maybe better said, an echo chamber. Any fan mail or other feedback from players of those games had never reached him because neither California Pacific nor Sierra had bothered to forward it to him. Once Ultima III came out under his own company’s aegis, however, he started getting a flood of letters telling him how fans really played his games. This generally entailed lots of murdering, stealing, and all-around reprehensible behavior. Now, it’s perhaps a bit surprising that this should come as such a shock to Richard, since those early games essentially forced this behavior on the player if she wished to succeed. Still, the letters set it all out in unmistakeable black and white, as it were. And then there were the truly crazy letters from religious fundamentalists and anti-Dungeons and Dragons activists, which included such lovely epithets as “Satanic perverter of America’s youth.”

The first few of those letters that I got at the age of 22 really bothered me. You sit back and go, “Gosh, I know I’m not a wicked individual, I know I’m not teaching Satan worship, I know I’m not doing any of these things.” But the fact that someone would think so bothered me. It made me want to call the person up and say, “Look, you’re wrong, you just misinterpreted it.” But of course it would do no good to do so.

“People,” Richard said in another interview, “read things into my games that were simply statistical anomalies in the programming. They thought I was putting messages into the game.” To his mind, those first four games were all simply “here’s some money, here’s some weapons, here’s some monsters, go kill them and you win.” Like the Beatles a generation earlier, he now decided to give those who wanted hidden messages something that actually, you know, existed to think about it. Less facetiously, all of this feedback did make him begin to think seriously for the first time about the sorts of messages his games were delivering, to begin to understand they were not “just games,” that they could and did say something about the world. He began to understand that every creative work says something, whether its creator intends it to do so or not. It says something about the person who created it, the culture he came from, the audience to which it’s expected to appeal. Richard wasn’t sure he liked what his games were saying — albeit all but unbeknownst to their creator — so he decided to take conscious control of his message with Ultima IV.

It makes for kind of a beautiful story about a young man discovering himself as an artist, discovering that the work he puts into the world really does matter. And there’s no reason to believe it isn’t true in the large strokes. That said, there are indications that the full story may be at least a bit more complicated than the glib summary that Richard has given in almost thirty years worth of interviews.

In the November 1983 issue of Softline magazine is an interview with Richard in which he describes his plans for the nascent Ultima IV. Already at this stage the player’s goal was to become an enlightened avatar by acquiring sixteen attributes — twice as many as in the finished game.

Fifteen attributes represent powers over forces of nature and life, and the final attribute is clairvoyance. The first fifteen attributes may be obtained through certain great deeds in the physical world: areas like those portrayed by all the previous Ultima games. For the final attribute, the adventurer must make a quest into the ninth plane of Hell (presumably through all the lesser planes as well).

The article goes on to state that the resolutely non-bookish Richard had read Dante’s Inferno by way of preparation, “so we can expect the depictions of the planes to be vivid and graphic.”

This is fascinating stuff on a couple of levels. It’s of course always interesting to see how a major work like Ultima IV evolved (if you didn’t find it so, I assume you wouldn’t be reading this blog). It’s interesting that sixteen “attributes” — a word that positively reeks of Dungeons and Dragons — became a more manageable eight virtues. It’s interesting to note how Dante’s Hell turned into the more abstract Stygian Abyss of the final game, doubtless a very wise decision in light of the easily outraged folks already convinced that fantasy role-playing in general and Ultima in particular were the work of Satan. It’s interesting just to note the influence Dante had on Ultima IV, an influence which, for all the words that have been spilled about the game since its release, appears to have gone completely unremarked in all of them.

But perhaps most interesting of all is the timeline of all this. Given magazine lead times, the interview that led to this article must have been done bare weeks or days after Ultima III‘s release — hardly enough time to let Richard receive lots of fan mail and other feedback on the game, internalize it all, and proceed so far down the road to a response in the form of Ultima IV. If we take that as a given, it leaves open just two alternative possibilities: that Sierra at least had in fact been forwarding to Richard his fan mail (this wouldn’t hugely surprise me; demonizing those first two publishers who did so much to give him his start has unfortunately become one of Richard’s less noble hobbies in recent years), or that this feedback, when it arrived, would be a contributory factor to Ultima IV but not quite the prime motivator it’s become in Richard’s telling. With that in mind, let’s look at some of the other factors that may have been at play here.

It seems likely that the real point of genesis of Ultima IV was not a fan letter but rather a television documentary about the Dead Sea Scrolls. This program, mentioned by Richard in interviews but which I unfortunately haven’t been able to identify more specifically, apparently mentioned in passing the belief held by some Christians and Hindus that Jesus Christ visited India during the so-called “unknown years” of his life, that period between about age twelve and thirty which is not described in the New Testament or any other accepted record. Some such folks believe that Jesus was a Hindu “avatar,” a god descended to earth in human form. Richard was captivated by the concept. He wasn’t the first bright young person to seek in the religions of the East a spiritual alternative to the dogmatic rigidity of the Christianity that he saw around him in his daily life. His august company includes the likes of Roger Zelazny, Steve Jobs, and of course a certain four lads from Liverpool. “I am not a religious individual,” he once said, “but I do have difficulty with the scare tactics that religions use to teach ethics, saying you must be good or something bad will happen to you.”

But what was the religious history of the “not religious” Richard? He described it at greatest length to Shay Addams for The Official Book of Ultima:

My family did go to church when I was very young, but by the time I was in my teens we really didn’t. So I went to Sunday school at an interdenominational church, which was a very interesting upbringing because it was extremely interdenominational. I mean, all sorts of different sects of Christianity as well as Judaism and who knows what else — I was too young to know what else might have been there. But it was very interesting the way Sunday school was taught in this church, which I really believe was an amazingly responsible thing to do: they would read a Biblical story that had a moral to it, and they would tell you why this means achieved this end, and then say, “This is a story put in the Bible to teach this lesson.” Christians believe it because it was recorded in this way, and so on, and they would explain it to you not as “this is fact” but as “this is a story that exists for this purpose.”

Although I was a child, I accepted it as fact, literally, but they didn’t tell me this was fact — that you must believe or you are going to Hell. As an adult, I could reflect upon it and say, “I don’t have to believe that. I understand why it was told, and why it was recorded. But it is my choice as to whether I believe it or not.” My eldest brother is religious; myself and Robert are not. We had a choice, though, which is the point. That is why I find it amazingly responsible, the way they brought us up. My father, for instance, was not religious and my mother only somewhat religious, but they believed it was important that their children have that upbringing as a knowledge base, and they found a place where they could get it. So, we all got to make those choices as adults. I thought that was very responsible on my parents’ part and pretty rare.

The factors that made the notion of an interdenominational church so appealing to the pragmatic Richard were likely the same that drew him to the story of Jesus as Hindu avatar: an emphasis on shared spirituality and shared ethics over the niceties of religious dogma. He became fascinated with Hinduism and in particular with Hindu Yoga. Their influence would be all over that first conception of Ultima IV he outlined for Softline, and internalized somewhat more subtly into the finished game.

They have a belief that there are sixteen ways you could purify yourself. In one of these sixteen ways you would get some sort of power, spiritual power, based on that. Some Yogis can kind of like stop their heart and other bodily functions and things of this nature, and I believe these people can literally do those physical things. I’m not saying why they can do them, but apparently the biggest, most powerful Yogis can even do things like teleport themselves to other places on the planet, which I have never seen personally and am somewhat skeptical of, but you never know. But it’s a very interesting thing that the Hindus believe Christ was a very powerful Yogi who, when he studied with them, attained the most powerful level, the avatar. The culmination of Yogis is to become an avatar, and the definition of an avatar is someone who has purified themselves in all sixteen of these ways.

There are five ways of purifying your physical body, for example, and five ways of purifying your spirit, and so on, and the last one, the sixteenth way, was to become one with God Himself. Interestingly enough, to this day Hindus say there have been two avatars in existence throughout history: one was a woman who predates written history, and the second one was Christ.

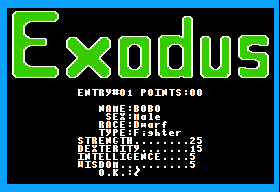

Garriott’s conception of Hinduism and Yoga is, shall we say, a somewhat idiosyncratic and confused one, steeped at least as much in Dungeons and Dragons and his work-hard-and-achieve upbringing as Hindu or Biblical scripture; this was after all still the kid who had named the villain in Ultima III “Exodus” just because it sounded cool. Thus we have Christ “leveling up” until he becomes an avatar — a word which itself means something different in Hinduism from what Richard seems to think it means — at level 16. Still, what Richard learned or thought he learned about Hinduism and Yoga would remain a critical piece of Ultima IV.

If we postulate a new concern with the messages that his games were sending and a renewed interest in religion — particularly Hinduism — as two legs of the three-legged stool on which rests Ultima IV, the last must be something even more universal: the simple life experience of growing up. Richard had, truth be told, lived a pretty sheltered existence to this point in the bosom of his family and NASA and his Dungeons and Dragons buddies and later of the University of Texas and his SCA troupe. Escapism, whether into fantasy or just the well-scrubbed safety of high-school science fairs, is an obvious running theme. By Richard’s own admission, he was if anything quite immature for his age when Origin decamped for New England. But now he was suddenly living in a house he and his friends were renting for themselves, far from home in the “frozen wastes” of Massachusetts. He was becoming an adult at last, with adult responsibilities.

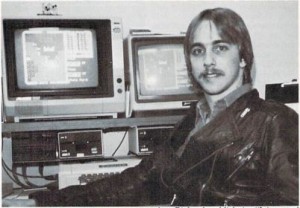

Richard started to feel his oats a bit during this period. He found his rather mild rebellious streak later than do many of us, but this did give him the luxury of something teenage rebels mostly lack: money. And so he replaced the practical car he had totaled in the snow with a new Mitsubishi Starion painted a striking jet black. He took to dressing in black leather pants and jacket, with studded bracelets around his wrists. He grew a single strand of hair into a long, braided pony tail that stretched beyond his shoulder blades. His relationship with his “extraordinarily conservative” brother and next-door neighbor Robert became decidedly strained; it seems Robert was usually more inclined to agree with his other neighbors than Richard regarding the latter’s parties and other antics. Warren Spector, a game designer who would become an important contributor to later Ultimas, was working as an assistant editor at Steve Jackson Games in Austin at this time. He describes the version of Richard that he glimpsed for the first time during one of the latter’s occasional return visits to Austin thus: “In drove this rock star in his Mitsubishi, all black. Got out, all black, bling everywhere. I was thinking, okay, I’m in the wrong line of work, I’ve got to find a way to work with this guy!”

The changes were not just external. Richard went through something of a minor existential crisis: “I wasn’t sure I knew what I was doing anymore. I tried to figure out who I was and what I was going to do next.” Trivial as it may sound, when Robert Garriott shook his head in embarrassment and the neighbors scowled at the body parts strewn across his lawn after Halloween or the empty trash cans that remained unretrieved at roadside for days on end, he was learning that actions — or, as the case may be, inaction — has consequences. All of these factors led Richard, like so many idealistically-inclined young men before him, to try to develop a philosophy of life that made sense to him. Richard was unique, however, in that he planned to put it all into a computer game — indeed, he saw doing so almost as a duty. He was well aware that the audience for his games was a pretty young and impressionable one, the most common demographic category being an adolescent boy.

If someone spends 100 hours playing my game, I have 100 hours of the input that makes that person what they are. With that comes, in my mind, a sense of responsibility regarding the content of what I’m going to pipeline into that individual for 100 hours. That was really the kernel thought that started what has now really changed Ultima henceforth and probably forever.

He set himself no less a task than the development of a complete code of ethics, a set of rules for living. As interesting as he found Hinduism and other religious traditions, it was very important to him that his rules for living must be explicitly divorced from any sort of supernatural agency. Some of the most brilliant thinkers in history, a list including Plato, Kant, and Nietzsche just for starters, devoted their lives to wrestling with the same task. Now the 22-year-old college drop-out Richard Garriott hung up a whiteboard, bought a stack of books, and prepared to do the same. The biggest issues he’d wrestled with for previous Ultimas were how many hit points this or that monster should have or how many experience points it should take to raise a character’s level. Now he was trying to devise a complete, internally consistent system of moral philosophy. It was a heady change indeed. Rather typically, Richard found the basic building blocks of the system of ethics he would finally include in Ultima IV not in any of the aforementioned highbrow philosophers but in The Wizard of Oz.

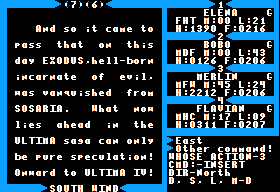

And that makes a pretty good place to stop for today. Next time we’ll look more closely at the ethical system he devised, along with much else in the finished game. Before I let you go, though, I do want to ask you to think about just what a remarkable conceptual leap Richard Garriott was making here, a leap made all the more remarkable by the fact that he did it all on its own, in a vacuum that still contained barely a whiff of our contemporary notions of serious games or ludic rhetoric, and in the genre of the CRPG that had heretofore been about little more than killing monsters and taking their stuff, with none of the higher-toned literary aspirations that Infocom and their competitors had brought to the text adventure.

Above all, it was — and I think this is a very important point with which to close — a tremendously brave choice. Richard was desperately worried about how it would be received by a public who expected just a bigger version of Ultima III. Should enough of those players accustomed to “kill, kill, kill” reject the game, it could bring down his company and put most of his closest friends out of work. The stress actually caused him to suffer the occasional panic attack while he programmed; his stomach would suddenly cramp up and he would have to lie down, willing himself to just breathe. “To succeed in this game,” he notes, “you had to radically change the way you’d ever played a game before.” This was the leap that the creators of Wizardry were unable to make, the one that transformed Ultima forevermore into something just a little bit nobler, a little bit more important, a little bit better than competing franchises. The fact that Richard was willing to make that leap, and that — yes, I’m sparing you the suspense — his public responded to it in huge numbers, makes it in its way as inspiring a story as any you’ll find in gaming history. Robert Gregg’s comments in Dungeons and Dreamers, describing the revelation that Ultima IV was to him when he first encountered it, offer the perfect closing thoughts: “The game was commenting on society, and on the observer himself, just like other forms of art. That was the most exciting part to me — watching the emergence of a new form of art, coming right off the computer.” You and me both, Robert.

(Sources for this article and the next include the books The Official Book of Ultima by Shay Addams, Dungeons and Dreamers by Brad King and John Borland, and Ultima: The Avatar Adventures by Rusel DeMaria and Caroline Spector; the Computer Gaming World issues of September/October 1984, November/December 1985, and March 1986; the Questbusters of August 1985; the Softline of November/December 1983; and the Commodore Power Play of August/September 1985. Also useful were Warren Spector’s video interview with Richard Garriott, and Matt Barton’s with Richard Garriott and with Chuck Bueche.)