When a beleaguered Netscape announced in January of 1998 that it would release the source code to its browser for everyone to tinker with and improve upon, the news shook the worlds of technology and business to their foundations. This open-source “revolution,” as even many in the mainstream press took to calling it, had sprung up seemingly out of nowhere to challenge the conventional wisdom and perhaps the very livelihood of traditional tech giants like Microsoft. For the next several years, you couldn’t open a trade journal or a newspaper’s business section without seeing some mention of the open-source movement and its leading exemplar, the robust and yet totally free — in all senses of the word — operating system Linux. Linux and other software like it was, an eye-opening number of people said, destined to destroy Microsoft’s vaunted Windows monopoly any day now.

The movement’s Little Red Book came in the form of Eric S. Raymond’s 1997 essay “The Cathedral and the Bazaar.” Originally presented as a comparison of a top-down versus a bottom-up methodology in the context of open-source projects, the central metaphor quickly got blurred in the minds of the public into a broader comparison of closed source versus open source, with Raymond’s tacit acquiescence. In this telling, the cathedral was Microsoft’s software-development model, in which a closeted priesthood bestowed programs upon a grateful populace on its own terms and on its own schedule. The bazaar was the hacker way, in which the people came together in a spirit of delightfully chaotic egalitarianism to make software for themselves, sharing their source code in the name of the greater good. “No closed-source developer can match the pool of talent the Linux community can bring to bear on a problem,” wrote Raymond. “The closed-source world cannot win an evolutionary arms race with open-source communities that can put orders of magnitude more skilled time into a problem.” Thanks to Linux and the other open-source tools it enabled, he predicted elsewhere, Microsoft’s eagerly anticipated Windows 2000, the latest incarnation of its server-grade NT operating system, would “be either cancelled or dead on arrival. Either way, it will turn into a horrendous train wreck, the worst strategic disaster in Microsoft’s history.”

Alas, Raymond proved a less effective prophet than pundit. Not only was it not a failure upon its eventual release, but Windows 2000 evolved in 2001 into the consumer-grade Windows XP, by many standards the most successful single version of Windows in history.

Like that of all revolutions that have passed their heyday of strident ideology, the most extreme rhetoric of the late 1990s open-source movement can seem overheated if not downright silly today, the blinkered product of a tiny strata of metaphorical inside cats who have concluded, rather conveniently for themselves, that the most important social-justice campaign of their age is one that can be waged from behind their keyboards and monitors, just the place where they happen to feel most comfortable. As for the ideas they introduced into the public discourse: they were real, valid, and in many ways incredibly valuable, but in the end they would be woven into the fabric of existing corporate-software production practices rather than burning down the old ways wholesale.

For rigid ideology seldom makes a good fit with the real world; pragmatically mixed national economies, for example, succeed vastly better than dogmatically capitalist or communist ones. Similarly, instead of continuing to sort itself into two opposing camps at eternal loggerheads, the modern software ecosystem has learned to take the best from both sides to wind up with a sort of mixed economy of its own. The cleverest actors have learned to combine the cathedral and the bazaar in ways that maximize the strengths of each: Google builds its proprietary Web browser Chrome atop an open-source engine known as Chromium; Apple constructed the OS X desktop on the solid foundation of an open-source operating system known as Darwin; Android mobile phones and tablets have Linux at their core. Even Microsoft now embeds an optional “Linux subsystem” into Windows, as the cats lie down with the dogs.

The reasons for open source’s failure to more comprehensively conquer the world aren’t that hard to divine; they’re actually front and center in some of the movement’s founding principles. The editors of the grandiosely titled 1999 anthology Open Sources: Voices from the Revolution — one of those books whose very name clues you into the window of time in which it was published — wrote that “most open-source projects began with frustration: looking for a tool to do a job and finding none, or finding one that was broken or poorly maintained. Eric Raymond began fetchmail this way; Larry Wall began Perl this way; Linus Torvalds began Linux this way.” The latter two of these projects at least have remained among the most essential of the workhorses that make the Internet function, strong arguments for the superiority of the open-source model for developing some types of software.

But it appears that the same is not true for all types of software. A model in which programmers create only the programs that they most want to have threatens to yield a universe of software which is interesting and attractive only to programmers. Even Eric Raymond had to acknowledge that the production of software with mass appeal is only partially a “technical problem.”

It’s [also] a problem in ergonomic design and interface psychology, and hackers have historically been poor at it. That is, while hackers can be very good at designing interfaces for other hackers, they tend to be poor at modeling the thought processes of the other 95 percent of the population well enough to write interfaces that J. Random End-User and his Aunt Tillie will pay to buy. Computers are tools for human beings. Ultimately, therefore, the challenges of designing hardware and software must come back to designing for human beings — all human beings.

Open source has never entirely made this leap. It’s for this reason that its biggest success stories have come in the realm of back-end software rather than user-facing applications. Witness the long, frustrating history of “Linux on the desktop,” which, in an echo of the old hacker joke about strong artificial intelligence, has been perpetually just a few years away from world domination ever since the late 1990s. There is no theoretical bar to visual designers and experts in ergonomic psychology joining open-source projects, and in some times and places this has even happened. And yet the broad field of open source is still dominated by programmers writing software for themselves and for one another.

Game development joins graphical user interfaces as another notable area where the bazaar model doesn’t quite seem to do the trick. The open-source methodology excels at solving purely technical problems, but the making of a great game is a technical problem only in part — usually, not even the most important part. Consider the case of one of the most critically lauded games of the late 1990s, Valve’s Half-Life. It was a triumph of design and aesthetics, not of technology; its engine was borrowed from id Software’s two-and-a-half-year-old Quake, a technological showstopper in its day which has aged far less gracefully. It would seem that the best way — or perhaps the only way – to create a great game from whole cloth is through a priesthood with a strong and distinctive design and aesthetic vision.

Those open-source games which have become relatively popular have tended to build upon previous game designers’ visions in much the same way that Chrome is built on Chromium: think FreeCiv or Open Transport Tycoon Deluxe, worthy projects that are nevertheless more interested in making workmanlike technical improvements to their inspirations than bold fundamental leaps in design. The open-source movement has had the most pronounced impact on gaming in the form of tools, both for making games and for playing them. I could never have embarked with you on this journey through history that we’ve been on for over a decade now without the likes of DOSBox, ScummVM, UAE, VICE, and many, many other open-source emulators and utilities of all descriptions. I am deeply grateful to the many talented programmers who have given their time to them in order to keep our digital past accessible. Still, they do remain purely technical projects, not creative ones in the sense of the games which they enable to run on modern hardware.

The one ghetto of gaming where open-source projects have been able to forge a strong design and aesthetic sensibility all their own — a sensibility with no obvious antecedents in commercial, closed-source games — turns out upon examination to be not quite the anomaly it might first appear. The “roguelike” sub-genre of the CRPG dates all the way back to 1980, well before the modern open-source movement came to be. But, like that movement, it was a product of an institutional-computing hacker culture that had been around since the 1950s, in which proprietary software was regarded as not so much immoral as simply unheard of. It stands today as a fine example of open source at its best — and equally of what it does less well. Call it the exception that proves the rule.

In Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution, his classic chronicle of the first few decades of institutional hackerdom, Steven Levy writes about the appeal that Adventure, a game that would lend its name to an entire genre, held for the first people to play it on the big multi-user DEC computers of the late 1970s.

In a sense, Adventure was a metaphor for computer programming itself — the deep recesses you explored in the Adventure world were akin to the basic, most obscure levels of the machine that you’d be traveling in when you hacked assembly code. You could get dizzy trying to remember where you were in both activities. Indeed, Adventure proved as addicting as programming…

Rogue, a game which would lend its name to a sub-genre that had even more appeal to the programming mindset, was itself a direct outgrowth of Adventure, with a couple of key elements added to the mix.

Michael Toy and Glenn Wichman were undergraduates at the University of California, Santa Cruz when they first encountered Adventure. Like so many others, they were absolutely entranced. The only drawback was that, once they finally beat the game for the first time, there wasn’t much more to be done; the puzzles were always the same, meaning that beating it again became a rote exercise. And there weren’t yet any other games like it. So, the pair started to talk about creating a game of their own, one that would play a little bit differently. What if, rather than building their game around a collection of pre-crafted set-piece puzzles, they made one that would offer up a new world to the player every single time through the magic of random procedural generation? That way, you could keep playing it forever, even after beating it once or twice or a dozen times. Even Toy and Wichman themselves would be able to have fun with it, given that they too would never know what sort of world they would be entering next.

But what exactly might such a game look like in practice? It wasn’t at all clear; the problem of describing a procedurally generated world in English prose like that used by Adventure was effectively insoluble in the context of the time. Then Toy stumbled upon a new programming library for the Unix operating system (the predecessor to and inspiration of Linux). The brainchild of a University of California, Berkeley student named Ken Arnold, “curses” let you arrange text however you wanted on a terminal screen, letting you change the contents of any one of the 1920 cells that made up a typical 80-character by 24-line display any time you wanted to; this made it possible to reserve different regions of the display for different sorts of information. Earlier games which hadn’t had access to curses, such as Adventure, had had to content themselves with teletype-like interactions: a continuous scrolling stream of text which, once fired at the screen, could only be forgotten. But curses changed all that at a stroke. You could use it to put up menus, maps, charts, and just about anything else you could write or draw using the ASCII character set, updating them all independently of one another.

It gave Toy and Wichman a viable path forward with their fondly imagined infinitely replayable game. For, while textual descriptions of a procedurally generated world were a nonstarter, showing a symbolic, visual representation of one using curses was another matter.

Avid players of tabletop Dungeons & Dragons, Toy and Wichman tried to recreate on the computer the dungeon-delving expeditions they enjoyed with their friends, exploring a network of rooms and tunnels filled with monsters to fight, traps and other hindrances to defuse, and treasures to collect. Whereas the main dish of Adventure had been set-piece puzzles, with only a side dish of dynamic logistical challenges — an expiring light source, an inventory limit, a pesky wandering thief with a sharp sword — the nature of their game meant that it would have to be all logistics. In making this switch, they half-accidentally invented not just the first roguelike but one of the first CRPGs, full stop. We cannot give them complete credit for that genre, mind you: other proto-CRPGs were being created at the same time on the PLATO system at the University of Illinois and on the earliest home microcomputers as well, as other Dungeons & Dragons fanatics also tried to bring the tabletop experience to the computer. Still, by all indications Toy and Wichman made the leap without knowing what anyone else was up to.

It was Wichman who came up with the name of Rogue:

I think the name just came to me. Names needed to be short because you invoked a program by typing its name in a command line. I liked the idea of a rogue. We were coming from a Dungeons & Dragons background, but we were creating a single-player game. You weren’t going down into the dungeon with a party. The idea was that this is a person going off on his or her own. It captured the theme very succinctly.

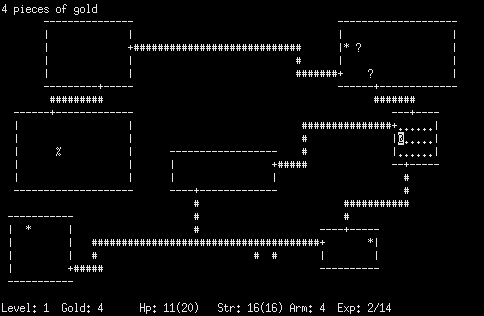

To depict their world, Toy and Wichman invented the iconography (textography?) that has remained the standard for roguelikes to this day. The walls of rooms were made from horizontal and vertical dashes (“-” and “|”), the tunnels between them from hash marks (“#”), doors from plus signs (“+”), treasure from dollar signs (“$”), monsters of varius types from any and all letters and symbols that weren’t already being used for something else. The focus of it all was your titular rogue, depicted as a forlorn little at-sign (“@”) adrift in this sea of promise and danger. The textual austerity of it all could become weirdly atmospheric. “You’d see a letter ‘T’ on the screen and it would startle you, because you knew it was a troll,” says Wichman.

The goal of the game was to find a MacGuffin called the Amulet of Yendor, hidden 25 dungeon levels or so deep, and return it to the surface. Doing so would require fighting ever more dangerous monsters, building up your character as you did so in classic RPG fashion, both through the experience points you gained from killing them and the equipment you collected. From the first, Rogue was intended to be hard — hard enough to challenge the very people who had made it. This is another quality that has remained a core value of the sub-genre which Rogue invented.

You didn’t know what the stuff you found actually did. Would that yellow potion restore your health, or would it kill you instantly? The safest way to know for sure was to use an “identification” scroll on your new finds, but such things were rare and precious, and ironically had to be themselves identified first. In a pinch, you might just have to try on that new ring or armor and see what happened, praying as you did so that it wasn’t cursed.

Food was the most essential resource of all; while you could eat the corpses of many monsters, some of them would make you sick and some of them would get their posthumous revenge by outright killing you. (Roguelikes are a bit like the old saw about the Australian Outback: everything in them seems to be able to kill you.) The only way to have a chance of winning was to play the game over and over again, slowly ferreting out its secrets and devising optimal strategies in the course of dying again and again and again. Even once you got really good, the difference between success and failure could still come down to sheer dumb luck, as “CRPG Addict” Chet Bolingbroke noted in his articles about the game: “Sometimes you might find a two-handed sword +1 on the first level; other times, you’ll find three poison potions and a cursed dagger.” Rogue‘s own co-creator Glenn Wichman admits that he has never legitimately won it.

Rogue, in other words, flagrantly violated almost all of the modern rules of progressive game design: it was unfair in countless ways and about as unwelcoming to newcomers as a game can be. It was a comedian telling jokes at the poor player’s expense, its later levels stocked with rust monsters that instantly destroyed her hard-won magical armor (until she learned to take it off before fighting them) and rattlesnakes that poisoned her (until she learned that the only practical way to combat them was to chuck whatever junk was to hand at them from a distance). And death was an irrevocable state. Although you could save a game of Rogue and come back to it later, this was intended only for the purpose of resuming an interrupted session: the save file was deleted as soon as you restored it. There were no second chances in Rogue; a single ill-considered move, or a single errant key press, or just a simple stroke of random bad luck, could and usually did erase hours of careful, steady progress.

And yet people found it strangely compelling. This was doubtless partially down to the times; there weren’t a lot of games available to play, which meant that the amount of time and energy required to get good at this one could seem more like an advantage than a disadvantage. But there was also more to it than that, as is indicated by the survival of the roguelike sub-genre right down to the present day, with all of its legendary difficulty intact. Rogue seemed to scratch a different itch than most games, a rash from which hackers seemed particularly prone to suffer. Very few successfully retrieved the Amulet of Yendor, but that only made the prospect of doing so that much more tempting. In the hyper-competitive culture of hackerdom, beating Rogue became a badge of honor almost on a par with writing some super-useful, super-elegant program that made everyone else jealous.

All of this didn’t happen instantly. Like most games on the big institutional computers, Rogue was a work in progress for years after the first version of it went up at UC Santa Cruz, probably in 1980. In 1982, Michael Toy got kicked out of the university for spending too much time tinkering with Rogue and not enough keeping up with his classwork. He took a job in UC Berkeley’s computer lab instead, splintering the partnership that had taken Rogue this far. Wichman now dropped off the scene, to be replaced at Berkeley by, of all people, Ken Arnold, the very hacker whose curses library had inspired the initial creation of Rogue. Toy and Arnold continued to expand and refine the game until they left Berkeley in 1984.

It was during this period that Rogue got really popular, spreading far and wide with the Unix operating system on which it ran, by now the overwhelming hacker favorite. Rogue became an almost equivalent touchstone of hacker culture, being played obsessively everywhere from Bell Labs to the Nevada Test Site. The game’s creators were thrilled when they learned that both Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie — living gods among hackers, the creators of Unix itself — were major fans of the game; Ritchie jokingly called it the biggest single waster of CPU cycles in computing history. When Toy attempted to commercialize Rogue in 1984 by releasing an MS-DOS port through the publisher Epyx, he felt justified in advertising it as “the most popular game running on Unix” and “the most popular game on college campuses.”

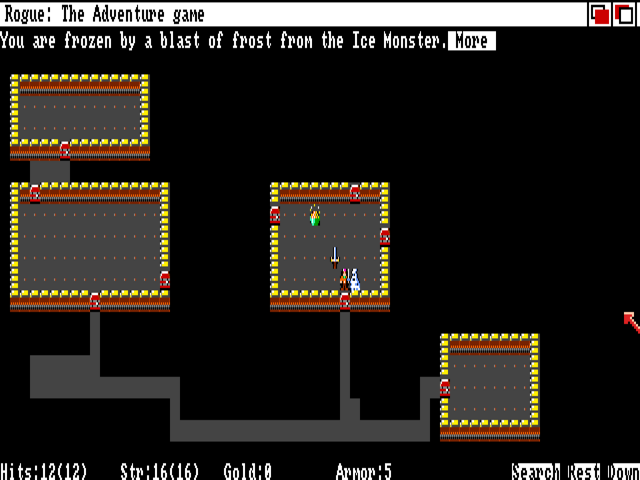

By the time Rogue hit microcomputers, its partial inspiration Adventure had spawned its own thriving corner of the home-computer-games market, where companies like Infocom sold hundreds of thousands of slickly packaged parser-driven text adventures. But home users proved markedly less receptive to Rogue after its belated arrival. Even after Wichman came back on the scene to help Toy make prettier, semi-graphical versions of the game for the Apple Macintosh, Atari ST, and Commodore Amiga, Rogue didn’t sell all that many copies. Wichman could only conclude that the audience that had made it such a hit on the big computers “wasn’t the audience that was looking for games in software stores.” It was a fair assessment: roguelikes would remain staples of hacker culture, but would never make inroads into the flashier commercial-games market.

Epyx’s Rogue was one of the last artifacts of that company’s original, cerebral “Automated Simulations” identity, appearing the same year that Summer Games and Impossible Mission cemented its new image as a purveyor of slick, audiovisually polished, action-oriented titles. Small wonder that Rogue seemed to get lost in the marketing shuffle.

In this as in so many other respects, Rogue laid down the template for all of the roguelikes to come as thoroughly as Adventure did for its progeny. But there was one important exception, albeit one external to the game itself: Toy, Wichman, and Arnold didn’t release their source code to the public, clinging to the role of the high priests of a cathedral rather than embracing the bazaar model of software development. “In retrospect, it would have been better to share,” admits Arnold. Yet it isn’t that surprising that they didn’t. Open source had yet to become an ideological movement, even among the hardcore hacker contingent to which Rogue‘s fathers belonged. And they did, after all, have hopes of commercializing the game, even if those hopes ultimately failed to come to complete fruition.

As it was, the lack of source code meant that those who dreamed of building a better Rogue had no choice but to start from scratch. Among the first to do so was a group of boys who hung out together in the computer lab at Lincoln-Sudbury High School in Sudbury, Massachusetts, at the dawn of the 1980s. The school’s single modest DEC PDP-11 minicomputer wasn’t wired to the Internet, but the gang nevertheless encountered Rogue early in its history: in the summer of 1981, when their mentor, a young teacher named Brian Harvey, finagled an invitation for them to go out to Berkeley for a few weeks, to see what life was like in the big leagues of institutional computing. One of the kids who went was named Jay Fenlason. He fell in love with Rogue at first sight, managing to play it for about eight hours by his own estimate during the visit. He returned to Massachusetts determined to make a game just like it. He corralled his buddies into an unlikely game-development team, and over the course of the next year they made Hack, working strictly from their memories of the game they had seen at Berkeley.

That initial version of Hack has been lost, leaving behind only scattered anecdotes. However, all indications are that it wasn’t any remarkable advance over Rogue in itself. What made it important — indeed, what changed everything for the nascent roguelike sub-genre — was the decision Fenlason and his friends made to give away not just their executable but their source code as well.

To celebrate their graduation in 1982, the computer-lab gang packaged up the source code to all of the programs they had written, Hack among them, and sent it to an organization called USENIX, a computing-research nonprofit that maintained a file archive for its members. The source bore a simple notice at the top, saying that anyone who wished to was free to make improvements to the software and distribute them, as long as due credit was given to the original creators as well and as long as they shared the updated source. Having done that, the youngsters who had made Hack went their separate ways, having no idea what the game they had loosed upon the world would someday grow into.

At first, their lack of expectations seemed more than justified; while Rogue went everywhere in hackerdom, Hack went nowhere. Then, in early 1984, a thirty-something Dutch mathematician and programmer named Andries Brouwer, who worked at the Amsterdam research center Mathematisch Centrum, chanced to troll through USENIX’s file archive, looking for interesting software. Just as Don Woods had rescued Will Crowther’s incomplete game of Adventure from oblivion back in 1977, Brouwer now stumbled across Hack and did it the same service. He tightened up the code and the gameplay, and then started adding new features, which he tested on his colleagues at Mathematisch Centrum, most of whom became certifiable Hack addicts. Beginning on December 17, 1984, he uploaded each new version to the Internet as well.

Brouwer added the concept of character classes to the game, introducing six of them; no rogue was to be found among them, but they did include the likes of a tourist and an archeologist, evidence of a quirky sense of humor that would continue to mark the game forevermore. He added shops in the dungeon for buying and selling equipment, and made the dungeon deeper; it now went down 40 levels, the last ten a special region called Hell that demanded magical protection from fire and a teleport spell to even enter. No longer did you find the Amulet of Yendor just lying around somewhere down there in the depths; now you had to defeat a Wizard of Yendor to get your mitts on it. To these big enhancements he added a wealth of smaller details that were likewise destined to remain indelible parts of the game, such as a dog or cat companion to accompany you on your expedition and the ability to write messages on the floor for various purposes.

For years, players of Rogue had been sharing their tips and travails on the Usenet group net.games.rogue. It was here that Brouwer now announced his new roguelike. The community there pounced upon Hack, which, if not clearly better than Rogue, did have the virtue of being subtly different from a game which most of them had already played to death. The volume of Hack-related traffic grew so extreme that, just one month after Brouwer had uploaded his game for the first time, the group net.games.hack came into being to accommodate it. “Please stop posting articles about Hack to net.games.rogue and use this new group instead,” wrote a Usenet administrator pointedly.

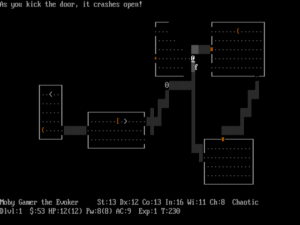

Brouwer kept his fire hose of additions and improvements spurting until July of 1985, when he pronounced himself satisfied with the game and moved on to other things. But, thanks to the fact that he had honored the wishes of Jay Fenlason and company and publicly released his source code, Hack could continue to morph and grow after his departure in a way that Rogue had not been able to after Michael Toy and Ken Arnold left Berkeley. Ports and modified versions were soon popping up everywhere. It was exciting in a way, but it became a bit too much like the babble of a bazaar. Three hackers, by the names of Mike Stephenson, Izchak Miller, and Janet Walz, decided that a little bureaucracy wouldn’t be amiss. They decided to create a sort of curated version of the game, incorporating changes from anyone who wished to contribute to the project, as long as they were well-coded, worthwhile, and not game-breaking. Because their home base was net.games.hack, they named their version of the game NetHack. Its first official release came in July of 1987; its most recent one as of this writing came out in February of 2023. I suspect that there will be many, many more before NetHack‘s full history can be written.

NetHack is an answer for every player of traditional adventure games who has ever asked why she can’t just bash a door open instead of searching hither and yon for the key.

The semi-anonymous wizards behind the NetHack curtain are known simply as the DevTeam. For 36 years, this rotating cast of characters has maintained and added to the game, making it one of if not the most systemically complex ever created, even as it retains in its canonical version an entirely textual display focused around a little wandering at-sign. Experienced players delight in ferreting out the emergent possibilities provided by the sheer depth of NetHack‘s systems. “The DevTeam thinks of everything,” goes a saying among players.

To wit: use a pair of gloves to pick up a dead cockatrice, a creature which turns any living thing it touches to stone, then bash your enemies with it to turn them to stone. (This technique is known among the NetHack cognoscenti as “wielding the rubber chicken.”) Of course, you’ll need to use a pick axe afterward to separate the statues of your enemies that are left behind from the loot they were carrying…

Or combine a Wand of Polymorph with a Ring of Polymorph Control to eliminate the middleman, as it were, turning yourself into a cockatrice. You can lay eggs in this form, which you can pick up and carry around once you revert to your natural form, throwing them at your enemies like grenades while you gleefully sing “Rainy Day Women #12 and 35.”

The possibilities are endless. NetHack even keeps track of the phases of the moon in the real world and uses them to influence your luck; this leads to devotees clearing their calendars once per month in order to maximize their chances when the moon is full.

NetHack has become an institution of old-school hacker culture, and with it an icon of the open-source movement. None other than Eric Raymond was the first to create an optional graphical skin for the game (a move that prompted considerable controversy). And well before he wrote The Cathedral and the Bazaar, he wrote the first manual for NetHack. Small wonder that it joined Rogue and Adventure as one of the very few games memorialized in 1996’s New Hacker’s Dictionary — edited by, you guessed it, Eric S. Raymond. DevTeam founding member Mike Stephenson has no doubts about NetHack‘s importance, not only as a standalone game but as a model for software development: “We predated open source [as a movement], but I do think we helped to promote the idea of making software available for public use without cost. I think the other thing that really contributed to the concept of open source is that NetHack has, and still does, accept bug reports and feature ideas from anyone.”

NetHack became the standard bearer of the roguelike sub-genre almost from the moment of its first release, and has never had its status in this regard seriously challenged. That said, hundreds of other roguelikes were made after it, and some even before it. The most important among them are arguably Moria and Angband. The former arrived at a complete form already in 1983, when it became the first game of this type to offer an above-ground town to serve as a base for your dungeon expeditions; this gave it a significantly different feel, more like, to put things in the terms of Dungeons & Dragons, an ongoing campaign than a single adventure module. Moria directly inspired 1990’s Angband, a much more complex implementation of the same approach, which, like NetHack, is still in active development today. Some players prefer NetHack‘s relentlessly escalating challenge, others Angband‘s somewhat more relaxed pacing and more free-form structure — but make no mistake, Angband too will kill you in a heartbeat if you let your guard down. And in it as well, dead is dead, permanently.

This roguelike “family tree” shows how the most historically and currently popular games in the sub-genre relate to one another.

This brings us back around to a statement I made at the outset: that roguelikes are the exception that proves the rule of open-source game development — and just possibly of open-source software development in general. The cast of thousands who contribute to them do so in order to make exactly the games that they want to play, which in the abstract is the best of all possible reasons to make a game. The experience they end up with is, unsurprisingly, much like high-wire programming at its most advanced, presenting players with an immense, multi-faceted system to be explored and mastered. And there is absolutely nothing wrong with this.

Still, it does seem to me that roguelikes tend to bring out some of the worst as well as the best of the hacker ethic, what with their insistence that they’re only for the “hardcore” and their lack of empathy for the newcomer. Few things in this world are less attractive than a nerd beating his chest. Robert Koeneke, the creator of Moria, admits that while he was working on it, “if anyone managed to win, I immediately found out how, and ‘enhanced’ the game to make it harder.” Likewise, for every cool interaction to be discovered in NetHack, there’s a cheap, heartless death in store, like stumbling down a staircase whilst carrying a cockatrice and turning yourself to stone, or missing a stirrup whilst trying to mount a horse and breaking your neck, or incinerating yourself by firing off your Wand of Lightning too close to a wall, or getting killed by your own pet dog when you attempt to use your Ring of Conflict to get that nearby band of orcs fighting one another. NetHack is the sort of game that likes to give you a fake Amulet of Yendor, then laugh at you when you scurry all the way back to the surface with it and think you’re about to win.

As with so much in life, one’s relationship to roguelikes comes down to questions of priorities. As someone who likes to play a variety of games, I’ve never done more than dabble in these ones. For the time required to get even minimally competent at them is more than I’m willing to invest in any single game — or that I can invest, if I want to keep doing what I do on this site.

Meanwhile the amount of time and effort required to get good at a game like NetHack is staggering, even if you’re far smarter and more diligent than I am. It took Chet Bolingbroke 262 hours of trying to win at NetHack for the first time — and that was playing in a fashion that many purists would consider illegitimate, by looking up spoilers on the game’s many interconnected components rather than learning strictly through experience, not to mention playing an old version that is much less complex than the current ones. Was it worth the time investment? He has his doubts. “Permadeath just sucks,” he concludes. Even Eric Raymond feels today that NetHack may have gone too far: “There was a natural tendency for the devs to see the game from the point of view of someone who played it constantly and obsessively. Thus, over time, their notion of not making it ‘too easy’ gradually ratcheted up the difficulty level to the point where you really couldn’t enjoy it casually anymore.” NetHack displays, in other words, open-source software’s usual Achilles heel, its developers’ inability to put themselves in the shoes of people who aren’t just like them.

Then again, it isn’t as if this represents some deep moral failing; there’s nothing wrong with being niche. Many or most lovers of NetHack and other roguelikes have never won them and quite probably never will, finding satisfaction merely in the trying, in hoping to get a little further than last time and walk away with some entertaining stories to share. Far be it from me to begrudge them their pleasures. Although I doubt that I will ever become a big fan of roguelikes, I do derive a quiet sort of satisfaction from knowing that things so implacably committed to being their own idiosyncratic selves exist in this world.

And if roguelikes will never go mainstream, that doesn’t mean they haven’t influenced the mainstream. Next time, we’ll learn how one of the most popular of all the slick commercial games of the late 1990s grew out of this odd little corner of hackerdom…

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

(Sources: I highly recommend David L. Craddock’s book Dungeon H@acks: How NetHack, Angband, and Other Roguelikes Changed the Course of Video Games, a treasure trove of information that I have only touched upon here. The CRPG Addict blog is full of stories about what it’s like to actually play Rogue, Hack, 1987-vintage NetHack, 1989-vintage NetHack, Moria, and Angband among other roguelikes, along with some more historical notes. I’m immensely indebted to David for all of his original research and to Chet for spending the hundreds of hours on these games that I couldn’t spare.

Other print sources include the books Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution by Steven Levy, The Cathedral and the Bazaar: Musings on Linux and Open Source by an Accidental Revolutionary by Eric S. Raymond, and Open Sources: Voices from the Revolution edited by Chris DiBona, Sam Ockman, and Mark Stone; Byte of March 1984 and February 1987; Acorn User of February 1997; Computer Power User of March 2008. Other online sources include Glenn Wichman’s “Brief History of Rogue,” “The Best Game Ever” by Wagner James Au at Salon, “Playing the Open Source Game” by Shawn Hargreaves, “Freeing an Old Game” by Ben Asselstine at Free Software Magazine, and a retrospective on NetHack by Dave “Fargo” Kosak of GameSpy.

Much more information about all of the games mentioned in this article, and roguelikes in general, can be found at RogueBasin, as can download links for all of them.)