By far the two biggest CRPGs of 1981 — bigger in fact than any that had come before by an order of magnitude or two — were Wizardry and Ultima. So, it was natural enough that the two biggest CRPGs of 1982 were a pair of sequels to those games. Some things never change.

Wizardry: Knight of Diamonds appeared in March of 1982, barely six months after its predecessor. It was more what we would today call an expansion than a full-fledged sequel, requiring that the player transfer in her characters — of 13th level or above — from the previous game. Still, in 1982 as today, putting out a solid expansion with new content for a bestselling game was a perfectly justifiable move, whether viewed as a fan wanting more to do or just in the cold light of economics. After all, Wizardry I was selling like crazy and causing a minor sensation in the computer press, and customers were clamoring for more.

Given the short time Robert Woodhead and Andrew Greenberg had to prepare Knight of Diamonds, major improvements to the game system could hardly be expected. Yet they did a very good job of leveraging the engine and the construction tools they had built for the first game, offering six more dungeon levels for high-level characters who had presumably already vanquished the evil wizard Werdna in Wizardry I. If it lacked the shock of the new that had accompanied that game, Knight is in many ways a better, tighter design. The player’s quest this time is to assemble the magical paraphernalia of a legendary knight in order to rescue the kingdom of Llylgamyn from something or other — the usual CRPG drill. The six pieces are each housed on a separate level of the dungeon. This gives a welcome motivation to thoroughly explore each level which is largely absent from Wizardry I, whose dungeon levels 5 through 9 literally contain nothing of interest other than monsters to fight to build up the party’s strength. Woodhead and Greenberg also slightly tweaked the game balance by making it impossible for a side that surprises another to use magic spells during that first, free attack round they get as a result. This has the welcome result of excising a scenario Wizardry I players had come to know all too well: getting surprised by a group of high-level magic users who proceed to take out the entire party with area-effect spells before anyone can do anything in response. It’s still possible to get into similar trouble in Knight of Diamonds when encountering monsters with non-magical special attacks, but the occurrence becomes blessedly much less common. Other oddities that almost smack of being bugs in the original, such as the strange ineffectiveness of some spells against all but the lowest level enemies, are also fixed, and of course there are also plenty of new, high-level monsters to learn about and develop counter-strategies against. For anyone who enjoyed the first game, Knight of Diamonds delivers plenty of the same sort of fun, with even more strategic depth and an even better sense of design.

Woodhead and Greenberg, then, did the safe, conservative thing with their sequel, leveraging their existing tools to give the gaming public more of what they had loved before, and very quickly and with minimal drama at that. It was a commercially astute move, one of the last that the pair and Sir-Tech would make for a franchise that they would soon mismanage to the brink of oblivion. The story of Ultima II, by contrast, is much longer and messier, spanning eighteen months rather than six and involving major technical changes, business failures, and some minor crises in the life of the young Richard Garriott. The game that finally emerged is also longer, messier, and much more problematic than Knight of Diamonds, but in its gonzo way more inspiring.

After finishing Ultima I, one thing was absolutely clear to Garriott: he had ridden BASIC as far as it would take him. As impressive as his game was technically, it was also painfully slow to play, even with the addition of a handful of assembly-language routines provided by a friend from his old job at Computerland, Ken Arnold. BASIC was also inherently less memory-efficient, an important factor to consider as Garriott’s design ideas got ever more grandiose. He therefore decided that, rather than get started immediately on Ultima II, he would learn assembly language first. He called his publisher, California Pacific, to see if they could help him out. They put him in touch with their star action-game programmer, Tom Luhrs, currently riding high on his game Apple-oids, an Asteroids clone that replaced asteroids with apples. In Garriott’s own words, Luhrs “held his hand” through an intense, self-imposed assembly-language boot camp that lasted about a month during his summer break from university. Without further ado, Garriott then started coding on the project that would become Ultima II.

He returned to Austin in the fall of 1981 to begin his junior year at the University of Texas, even as his studies there increasingly took a back seat to computer games and his deep involvement with his SCA friends. One particular course that semester would serve as a catalyst which made him choose once and for all between committing wholeheartedly to a career in games or getting a degree.

The story of Garriott’s class in 6809 assembly-language programming is one that he’s told many times over the years to various interviewers, who have nevertheless tended to report it slightly differently. The outline is clear enough. The Motorola 6809 was the successor to the older 6800. Like its predecessor, the 6809 never became a tremendously common choice of microcomputer manufacturers, perhaps due to its relatively high price. It did, however, find a home in Radio Shack’s Color Computer line. More important to our purposes is to recall the relationship of the earlier Motorola 6800 to the MOS 6502. Chuck Peddle had worked on the 6800 at Motorola, then left to join MOS, where he designed the 6502 as the cost-reduced version of the 6800 that Motorola had not been interested in building; the 6502 used a subset of the 6800’s instruction set. When Garriott started in his assembly-language class, he therefore found he could do all of the assignments by simply writing 6502 code, an instruction set with which he was by now very familiar. Problem was, students were graded not just on whether their programs worked, but also on whether they were properly written, taking maximum advantage of the more efficient instruction set of the 6809. Suddenly Garriott found himself failing the class, even though his programs all worked perfectly well.

That’s the story that’s always told, anyway, a story that conveniently casts the professor teaching the course as a sort of rigid, establishment ogre shaking his finger in the face of the original, freethinking Garriott and his practical hacker ethic. One version of the story, however, found in the book Dungeons and Dreamers, paints a less than flattering picture of Garriott as well:

He refused to learn what the new processor could do. Why should he? He completed his assignments, but he refused to include the latest features of the new processor in his work. His professor wasn’t amused and knocked points off Richard’s grade for each successive sign of intractability. With each dropped point, Richard’s motivation waned until he finally hit bottom: an F in the class, and a determination to get out. He just couldn’t take the demands of the professor seriously.

What seems pretty clear, at least from this version, is that young Richard by this stage could already be a difficult person to deal with, arrogant and uninterested in compromise. There’s no reason we should really blame him for that today. Barely 20 years old, he was already featuring in glossy magazines under his nom de plume Lord British, selling many thousands of games and making a lot of money. (Although, as we’ll see shortly, exactly how much is another of those details that are still somewhat in question.) How many young men wouldn’t become a bit arrogant under those circumstances, uninterested in sitting through boring classes offering knowledge they didn’t feel they needed? Suffice to say that it’s worth remembering that there was a prickly side to Garriott as we continue his story in this post and later ones.

With the decision made to drop not only the class but also university entirely, Richard was faced with the daunting prospect of telling his family about it. Said family was, in his own words, “painfully overeducated.” With an astronaut father, he had been raised in a culture of extreme achievement, in which graduate degrees were not so much an achievement as a baseline expectation; both of his parents and, eventually, all three of his siblings would have one or more. Now Richard had to tell his father, a man very skeptical of this whole games thing anyway, that he was going to drop out well short of his undergraduate degree to pursue them full time. “We were pretty sure he was going to kill Richard,” remembered his brother Robert. The conversation first ended in an uneasy compromise, in which Richard would come back to Houston to devote most of his time to his game, but would take part-time classes at the University of Houston. This he did, albeit in somewhat desultory fashion, for about a year, until his father finally accepted that the games industry offered more opportunity than university for Richard at this moment. “When this ends,” said his father, “you’ll go back to school and get a real job.” That day, of course, would never come.

In the midst of the crisis of the 6809 class, another was also unfolding in Garriott’s life. California Pacific, the publisher who had discovered Akalabeth and whose head Al Remmers had named Ultima, hit the financial skids. At first blush it’s hard to understand how CP could be in trouble; Akalabeth and Ultima had both been big hits. They had other bestsellers in their stable as well, such as the aforementioned Apple-oids, in an era when profit margins were absolutely astronomical in comparison to anything that would come later. Garriott has claimed from time to time that Remmers and the others at CP all had huge drug habits, that they literally smoked up all of their profits (and then some) and ran their company out of business. While this is suitably dramatic, it should be remembered that Garriott was in Texas while CP was based in California, and that they rarely met personally. I asked around a bit, but could find no smoking gun, no one who remembered drugs to be any more of a factor at CP than at many of the other California publishers, where they sometimes hovered around the edges of corporate social lives but rarely (the sad story of Bob Davis aside) took center stage. It seems at least as likely that CP, like so many other companies in this era run by ex-hobbyists and hackers, simply lacked anything in the way of practical business sense. To Richard, raised in the straitlaced bosom of the Johnson Space Center, a joint or two on the weekend might not have been readily distinguishable from hardcore drug addiction.

Regardless of the cause, CP went under in late 1981 owing Garriott a substantial amount of money. When we ask how substantial, however, the picture immediately becomes unclear again. In places Garriott has claimed that he literally received nothing from CP for Ultima, that they paid him only for Akalabeth. Yet Dungeons and Dreamers claims that by the time he enrolled in that 6809 course he had made “hundreds of thousands of dollars,” a figure that seems difficult to attribute to Akalabeth alone. In an interview with Warren Spector, he stated that he was making “many times more” than his astronaut father by that time, and that Ultima had been “five to ten times” as lucrative as Akalabeth. Further complicating all of this are the chronological errors that are rife in accounts of Garriott’s early career, which I’ve written about before. Some accounts, for instance, have Garriott quitting university in the aftermath of Ultima II, which is clearly incorrect, and perhaps reflects a conflation of his stay at the University of Texas with that at the University of Houston. So all we can confidently say is that CP went out of business owing Garriott something, and that he is still rather angry about it to this day, referring to CP as “dumb” and “bozos” in that Warren Spector interview. (All of which seems rather harsh language to employ against the folks that discovered him, named the franchise that made him famous, and largely created the whole legend of his alter ego Lord British, but so be it.) He briefly brought in his older brother Robert, who was pursuing an MBA at MIT, to try to collect from the failed company, but found that the old adage about blood and turnips definitely applied in this case.

Garriott may have suddenly been without a publisher, but he was also one of the most well-known personalities in adventure gaming. Other companies immediately started calling. Richard, as we already noted, was feeling his oats a bit by this time. He proved to be a very demanding signee, wanting a very high royalty rate. But the real sticking point was his demand that his game be packaged with an elaborate cloth map. That odd demand — remember, this was still before Infocom revolutionized computer-game packaging with Deadline — was yet another legacy of that busy fall of 1981, when he’d first seen a new movie called Time Bandits.

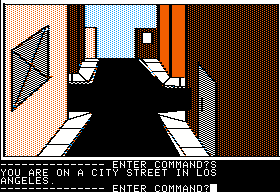

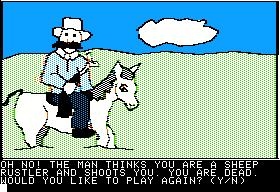

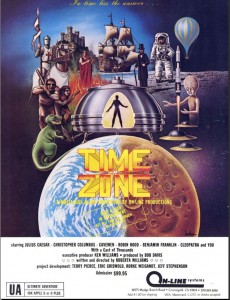

A production of George Harrison’s Handmade Films which involved many alumni of Monty Python, Time Bandits is the slightly manic story of a group of rogue dwarfs who go hopscotching through space and time with the aid of a map which charts gates or rips in the fabric of space-time that blink regularly in and out of existence. Garriott was of the perfect age and personality to fall for Monty Python’s brand of zany irreverence. What really fascinated him about the movie, though, and to an almost bizarre degree, was that map. He and his friends saw the movie again and again at the $1.00 matinee, trying to sketch as much of the map as they could from the brief glimpses of it they got during the movie. Richard, you see, thought that this mechanic would be perfect for his new game; he wanted to know how the map really worked. Eventually he came to the disillusioning realization that there was no logic to it, that it was a pretty prop and nothing more. Still, he wanted to put time gates in his game, and he wanted to include an ornate cloth map to chart them. As publishers soon learned to their chagrin, this was as un-negotiable as his royalty demands; Richard was willing to give up games and return to university for a “real” career if he couldn’t find someone willing to meet them. Luckily, in the end he did — and none other than On-Line Systems. Richard may have been difficult, but Ken Williams knew a software star when he saw one. By the time Ultima II was previewed in the March 1982 issue of Softline, the basics of its insanely ambitious design were all in place, including time travel to five different eras and space travel to all of the planets of the solar system. Also in place was the deal with On-Line.

Without the distractions of a full-time university course-load, Garriott could now work full-time on his new game. Yet progress proved slower than expected. He had jumped in at the deep end in attempting to code something as ambitious as this as literally his first assembly-language project, ever. Ken tried to be as patient and encouraging as possible, keeping his in-house programming staff available as a sort of technical-support hotline for Richard. When Richard truly looked to be foundering about mid-year, he invited him to stay in Oakhurst for a time in one of the flats he had bought up around town, to work in On-Line’s offices and enjoy the feedback and camaraderie of the group. It seems to be here that the relationship really began to deteriorate.

On-Line wasn’t exactly Animal House, but they did like to party and have their fun on occasion. Richard, who for all his early success and fame had nevertheless lived a very sheltered life, didn’t fit in at all. “I’m not sure they liked me,” he later said. I recently asked John Williams about Garriott’s time in Oakhurst. He stated that everyone did their best to welcome Richard. For his part, however, Richard showed no interest in attending parties or in any of the outdoor activities that just about everyone at On-Line enjoyed. Still, John stated:

On a personal level, I really liked Richard and I think most at Sierra did. He was scary smart, knew what he wanted and did what needed to be done to make it happen, and in general was just an impressive person. He was quite young then – but you could tell he was going places. I had no idea how far he would go then. Certainly I never would have guessed outer space – but if he had said he planned to go, I’d have believed him.

Perhaps the strains on Richard’s relationship with Ken arose from that very “impressiveness.” As John told me, “There are very few people as smart and driven as Ken — and Richard was one of them.” Both were accustomed to being the center of their social universes; after all, it’s not every kid who can convince his friends to spend hours in a movie theater watching the same film over and over, trying to copy an esoteric map onto paper from the most occasional onscreen glimpses. Ken could be gruff and even confrontational, particularly so with people he thought were really good but whom he also thought needed that extra push to reach their full potential. He may have thought Richard needed just this sort of pressure to finish a game On-Line had originally projected to release in April. Yet Richard, with two hit games under his belt and a big contract from Ken himself proving his worth, was unwilling to be treated as a junior partner in anything. Serious tension was the inevitable result.

At the end of it all Richard may have been heartily glad to return to the familiarity of suburban Houston, but his sojourn in California does seem to have accomplished Ken’s purpose of getting him onto some sort of track to just finish his game already. Ultima II finally appeared, complete with the cloth map and deluxe packaging Garriott had demanded, just in time for Christmas, and just as On-Line Systems changed their name to Sierra Online. (The original packaging uses the latter name, but the actual program still refers to the former.) For the game’s big debut on the all-important trade-show circuit, Garriott dutifully appeared in Sierra’s booth at that December’s San Francisco AppleFest as Lord British, dressed in his full SCA regalia.

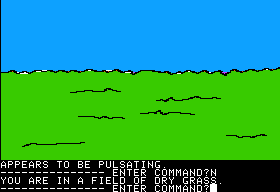

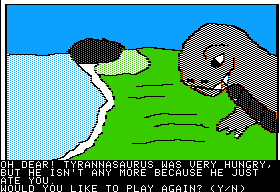

The game he was promoting had taken a full eighteen months to create, an unprecedentedly long time even in comparison to previous monster efforts like Sierra’s own Time Zone. Like that game, Ultima II proved to be a deeply flawed design, whose internal messiness echoed much of the stress and confusion that had marked its maker’s life over the months of development. At the same time, however, it may have been a necessary step on the way to the later, more celebrated Ultimas. We’ll talk about both aspects next time.