When we left Richard Garriott, California Pacific had just released his first game, Akalabeth, a substantial windfall for the 19-year-old university student. In between classes and SCA events, he spent his sophomore year at the University of Texas writing a new, much more ambitious game, which CP published just as the spring semester of 1981 was wrapping up. I think we can best proceed by just diving right into the game that retroactively came to be known as Ultima I.

Like Zork, making Ultima available here presented a bit of an ethical dilemma for me. You can actually now buy the first three Ultima games again via GOG.com, a service I can hardly applaud enough for keeping deep catalog works like these in print in a form easily runnable on modern PCs. However, the version they sell is the Origin Systems remake from 1986. It’s much more polished and playable than the original that Garriott wrote in BASIC on his Apple II Plus, but it’s of course also something of an anachronism for a digital antiquarian like me. So, I’m going to go ahead and offer here the original California Pacific Ultima as Apple II disk images along with the original accompanying documentation, at least until someone tells me not to. If you’re following closely along with my journey into the game, or want to do some digital archaeology of your own, have at it. If, on the other hand, you’re a bit less hardcore but your interest is piqued enough to want to give Ultima a shot, by all means go for the much more playable and accessible version you’ll find on Good Old Games — no emulator required.

By the standards of later Ultimas, the packaging of Ultima I is spartan: the two disks, a very to-the-point 10-page manual, and a player reference card that, oddly, includes important information not included in the manual (and vice versa). No lengthy books of lore, no cloth maps, no ankh medallions. Yet by the standards of its time, in which games were just transitioning from Ziploc baggies to more professional packaging (a symptom of the slowly encroaching professionalization of the industry as a whole), it’s a fairly generous production. More ephemerally, this first Ultima experience feels like the CRPG experience that so many fans would come to know over the next decade, the era Matt Barton calls the “Golden Age” of the CRPG: a big experience promising many hours of adventure from its garishly illustrated outside to the multiple disks found inside. (In fact, Ultima is the earliest game I know of to spill across more than a single disk side.) And that impression stems from more than just the details of its presentation. If Zork in some sense perfected the text adventure by hitting upon a robust approach to interactive fiction that still persists to this day, Ultima, one could argue, did much of the same for the CRPG. Like Zork, Ultima is perhaps the first example of its form that one might actually want to play today just to, you know, play. So let’s boot our Apple II and have at it, shall we?

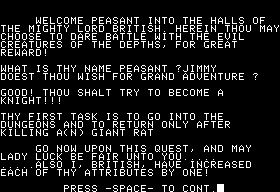

Until very shortly before its release, Ultima was not called Ultima, but rather Ultimatum. We can see evidence of this by listing the directories of the disks themselves; the file holding the title screen you see above is still titled “PIC.ULTIMATUM.” Why choose that name? Like so much in Garriott’s early games, simply because it sounded cool; certainly this title has no more bearing on the game’s plot, such as it is, than does the name Ultima. The change was made when Garriott and California Pacific discovered that there was already a tabletop war game in print under the name Ultimatum. Wishing to avoid confusion and legal complications, it was Al Remmers of CP who suggested that they shorten the name to simply Ultima because, once again, it sounded cool. (Later apologists’ attempts to construe the name as a reference to the semi-mythical classical land of ultima Thule are about as convincing as their attempts to construct a coherent narrative arc out of the random smorgasbord of plot and setting of the first three Ultima games.) Remmers, you may remember, also suggested that Garriott take his occasional nickname Lord British as his nom de plume, drumming up a promotional campaign for Akalabeth depicting Lord British as a reclusive and enigmatic genius. It’s ironic that Remmers, a guy that Garriott didn’t know that well and with whom he would soon have an ugly falling out, essentially created the two brand names for which Garriott will forever be remembered, while he himself faded quickly into obscurity. It’s also emblematic of the uncanny luck that seemed to follow young Garriott around, luck which brought various older and (possibly) wiser men to further his career almost in spite of themselves. Remember also John Mayer, his ComputerLand manager who convinced him to sell Akalabeth in the store and by some accounts was responsible for bringing it to the attention of Remmers and CP…

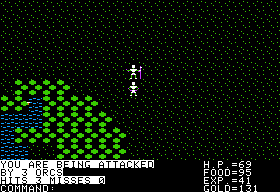

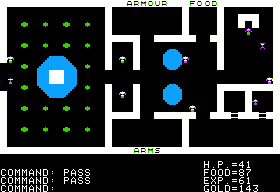

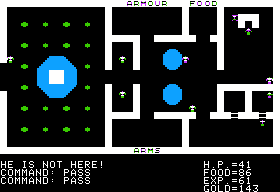

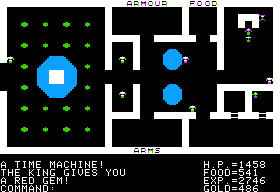

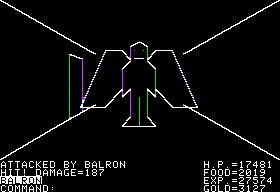

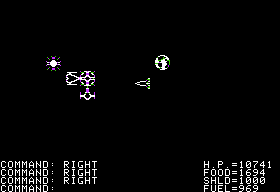

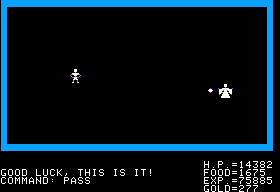

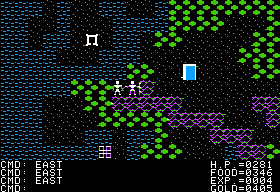

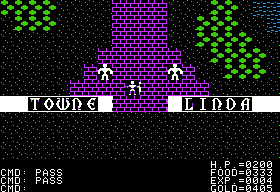

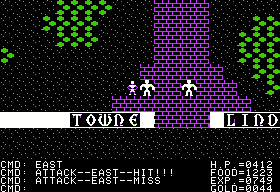

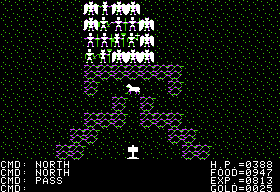

Just like Akalabeth, Ultima — shown on the right in the comparison above — dumps us into an overhead view of the outdoor landscape after we create our character. Unlike in Akalabeth, we now have monsters to contend with out here as well as in the dungeons. And if Ultima is still not exactly a graphical extravaganza, things sure do look a whole lot better than before, thanks largely to the game’s major technical innovation: tile graphics.

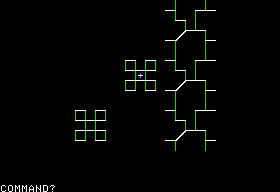

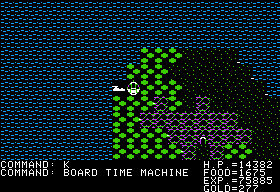

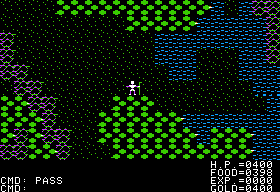

Ultima‘s world is a pretty big one, spanning four continents each many times the length and width of a single screen. At a resolution of 280 X 160, trying to draw all of this at the level of individual pixels would be untenable, both technically (even two disk sides couldn’t possibly store that much information) and practically (Garriott was just one guy, and not really an artist either; nor was the the Apple II’s library of graphics software terribly mature by this point). The solution was to draw the world using a collection of pre-rendered tiles, each 14 X 16 pixels. Each screen is thus formed from 200 of these tiles, in rows of 20 and columns of 10, laid together in a process that would feel kind of similar to doing a jigsaw puzzle or playing a tile-laying board game like Carcassonne. Ultima‘s world map is represented on the computer as just a grid of numbers specifying which tile should be slotted into which position by the graphics engine. It’s often claimed that Ultima represents the very first application of this technique that was soon everywhere in videogames of the 1980s, one that still crops up more than you might expect even today. Being a skeptical bastard by nature, I do wonder that no one thought of it in even the relatively brief history of videogames prior to Ultima; it does seem a fairly obvious approach, after all. On the other hand, I can’t point to a specific example that would give me grounds to really challenge the claim. As always, post ’em (or comment ’em) if you got ’em.

Ultima‘s tile-graphics engine was not so much the work of Garriott as of a friend of his who was the only other person to have a significant role in the game’s design and implementation: Ken W. Arnold (not the Ken Arnold who created Rogue). A neighborhood chum of Garriott’s, Arnold worked at the same ComputerLand store where Garriott spent that fateful summer of 1980. The two sketched out the initial plan for the game together when Garriott, excited by the sale of Akalabeth to California Pacific and beginning to realize he could make money at this stuff, began work on Ultima even before leaving again for university. Arnold not only invented the tile graphics scheme but also handled the technical implementation, writing an assembly-language routine to fetch the tiles and rapidly paint them onto the screen as the player moves about the world. This routine, along with another to generate the game’s simple combat sound effects, were the only parts of Ultima not to be written in BASIC. Garriott, unlike Arnold, had not yet learned assembly language, and thus implemented everything else in BASIC after leaving Arnold, Houston, and ComputerLand to return to university in Austin.

Even with the tile system, creating Ultima‘s graphics was a challenge. From The Official Book of Ultima:

“We had to actually enter all the shapes in hex,” Garriott says, detailing the primitive process. First he and Arnold would draw them out on graph paper, then convert the graphs to binary, which in turn had to be reversed because the pixels appeared on the screen backwards. After converting it into hex, they entered the tile as data, stored it on disk, and then ran it to see if it looked right on the screen. “We had no editors or anything, so it was a very painful thing.”

Indeed, one suspects that, even in the context of 1980-81, easier ways could have been devised. Put another way, young Richard and Ken had not yet learned the value of making programs to make programs. Still, stories like the above illustrate one of the most remarkable things about these early games of Garriott’s: they were created by a self-taught kid who literally figured things out as he went along, working on a single Apple II and with none of the technical background or resources of an Infocom or even an On-Line Systems or Muse to call upon. Their ramshackle technological underpinnings may be less elegant than the Z-Machine, but they are in their own way just as remarkable. In a very real sense it’s amazing that Ultima exists at all.

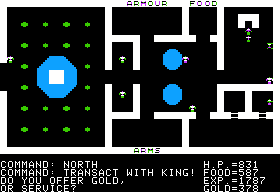

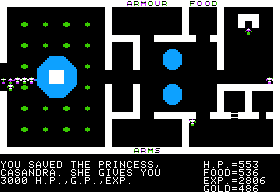

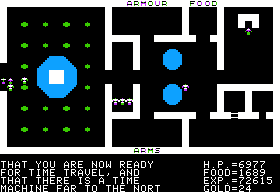

The world all of their labor lets us explore is based upon Garriott’s latest Dungeons and Dragons campaign world circa mid-1980, which he called Sosaria; he literally transcribed his D&D maps right into the game. As we’ll soon see, Sosaria is not exactly the most coherent of milieu. A person could also say that gameplay has not progressed all that much beyond Akalabeth: we still move around the wilderness map to visit towns (for our shopping needs), castles (for quests), and dungeons (for critter bashing). One is reminded once again of Garriott’s joking comment that he spent some 15 years making the same game again and again. The person who said Garriott hadn’t progressed much would be pretty unfair, however, because much has changed here too. Virtually everything is now bigger and more fleshed out, and there’s a big overarching quest to solve. In fact, the whole philosophy of the game has moved from the Akalabeth approach of being a relatively short, replayable experience to the extended, save-game-enabled epic journey CRPG fans would soon come to associate with the name Ultima.