Flipping through early issues of SoftSide magazine, one can’t help but notice a handful of people who are absolutely everywhere, churning out games, tools, applications, even feature articles at a dizzying pace. There’s Scott Adams, of course, who in addition to his adventures also wrote a variety of other card- and board-game adaptations and simple strategy games. There’s the Reverend George Blank, who in addition to editing the magazine and writing a pile of games and utilities for it also authored an article speculating on the possibilities for computer gaming:

Few good computer games have been written so far. Of the good ones, some are adaptations of games like chess and Othello [also known as Reversi] which existed first in another form. These games are good if they add a dimension to the play of the game that is not present in its original form (such as the possibility of solo play), and do so in an aesthetically pleasing form. My personal opinion is that such computer adaptations will play a trivial role in the future of computer games and the best ones will be those which take unique advantage of the computer’s capabilities.

And there’s the man who authored Dog Star Adventure for SoftSide‘s May 1979 issue, Lance Micklus. Before doing so Lance had already written and sold: Concentration (an adaptation of a classic game show); Robot (a maze game); Mastermind I and II (board-game adaptations); Breakaway (a pinball game); Treasure Hunt (a mapping exercise in the Hunt the Wumpus tradition); Renumber (a programmer’s utility); KVP Extender (keyboard utilities); and Personal Finance and Advanced Personal Finance (financial software). Most of all he was known for having written Star Trek III.3, a port of a classic space strategy game that originated on HP Time-Shared BASIC; and a suite of terminal emulation software that allowed TRS-80s to communicate with larger institutional machines and with each other via modem. Quite a portfolio, especially considering that Lance was not a seasoned programmer when he came to the TRS-80, having spent his career working as an electrical engineer in television and radio.

The TRS-80 was perhaps the ideal platform for fostering such Leonardos. Since its graphics capabilities were one step above nonexistent, art assets weren’t exactly a big concern. And then of course its sound capabilities were completely nonexistent, so strike that off the list. Combine this with the fact that 16 K of RAM places a sharp limit on possibilities even for the most ambitious, and virtually any program that was conceivable to implement on the TRS-80 at all was doable — and doable relatively quickly — by a single skilled programmer. There’s something kind of beautiful about that.

Another nice facet of these more innocent programming times was a blissful unawareness of intellectual property rights. Certainly the many adapters of copyrighted board games, not to mention that hugely popular Star Trek game, hadn’t signed contracts with the owners of their respective properties. Dog Star Adventure was “inspired” by the middle act of Star Wars, when the crew of the Millennium Falcon is trapped aboard the Death Star and must rescue Princess Leia and escape. It seems somebody got just a bit nervous this time, however, so the Death Star became the Dog Star, Princess Leia became Princess Leya, Darth Vader became General Doom… you get the picture.

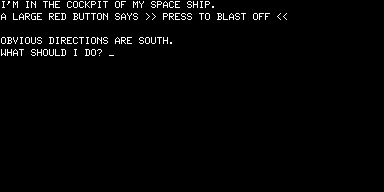

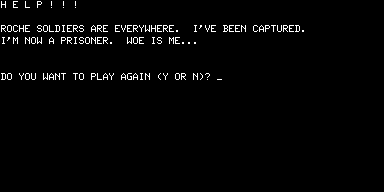

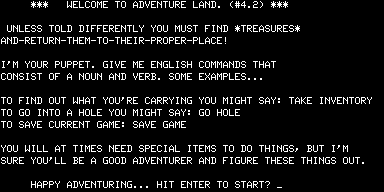

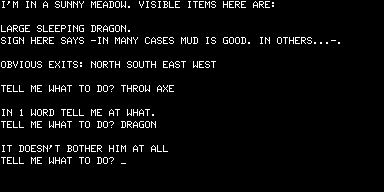

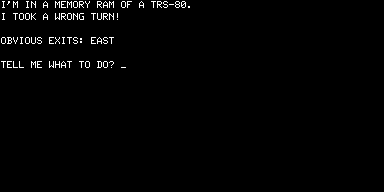

As soon as you start the game the debt it owes to Scott Adams is obvious. Here we see the bridge function that Adams’s early games served in action; Dog Star Adventure was inspired by Adams’s work, having been written by someone without exposure to Adams’s own inspiration of the original Adventure. (UPDATE: Um, not quite. See my brief interview with Lance for more on Dog Star’s influences.) Note the “Obvious Exits” convention, and the shift from second-person to first-person narration that Adams initiated with Adventureland:

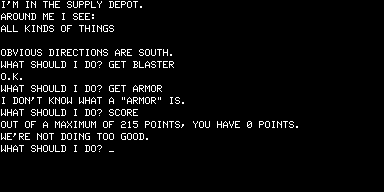

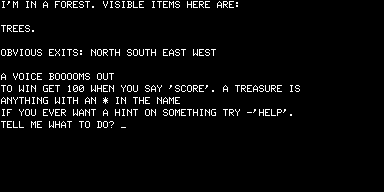

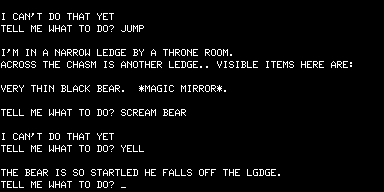

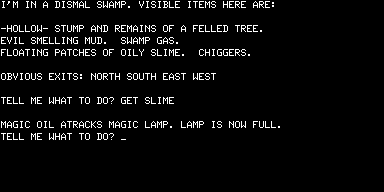

The game is somewhat easier than Adventureland, with fewer howlingly unfair puzzles, but it still has its dodgy moments, such as the storage area filled with “all kinds of stuff.”

Yes, you need some of that stuff; and yes, you have to guess what is there and what the game wants you to call it. I can’t quite decide whether I like this or hate it; there is a certain element of cleverness to the “puzzle” (imagine my satisfaction when I entered GET BLASTER and it worked).

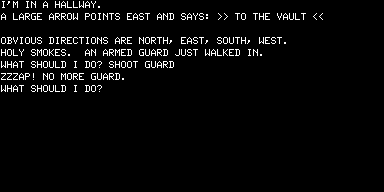

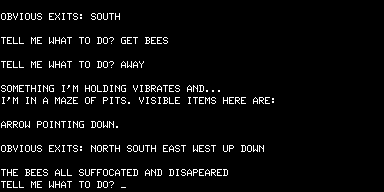

There are also packs of stormtroopers wandering the complex. Fortunately, you can use the aforementioned blaster to take them out.

Unfortunately (but inevitably), your blaster has a limited amount of ammunition, and you can only GET AMMUNITION once in the storage area. So, you’ll be seeing this quite a lot:

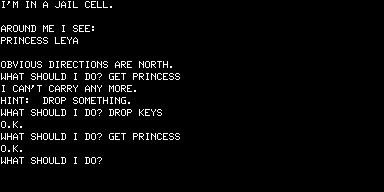

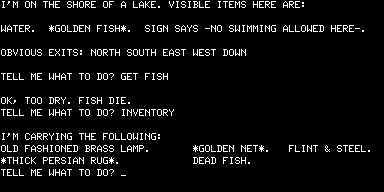

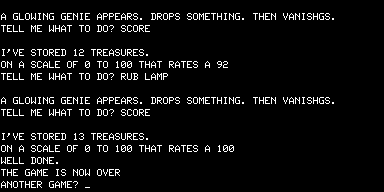

Superficially, your goal in Dog Star Adventure is the same that it was in Adventureland: gather a collection of treasures into a certain location (in this case, the cargo hold of your spaceship). Clearly Mr. Micklus didn’t get the memo about the Sexual Revolution, because even the Princess herself is implemented as just another takeable treasure.

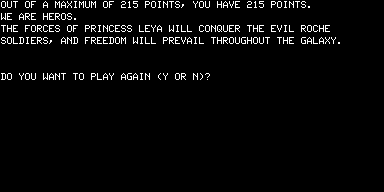

Look a little deeper, though, and you’ll find there’s something going on here that is very interesting. Instead of just collecting for hoarding’s sake, all of these treasures (presumably including the Princess) are actually good for something in the context of the plot. You’re collecting fuel for your spaceship; the Princess’s necklace, with a hidden computer chip that encodes “the location and strength of her Freedom Fighting Force”; General Doom’s battle plans, which you have recorded onto a TRS-80 cassette tape (maybe you should have made a few backups?). Nor does the game end immediately when you have collected all the treasures; you must still get the space station’s hangar doors opened somehow and launch your ship. It’s not exactly compelling drama, but there’s the skeleton of a real plot arc here, climaxing in triumph for the Rebel… er, for the Forces of Freedom.

In addition to being available on tape from The TRS-80 Software Exchange for the low, low price of $9.95, the complete Dogstar Adventure was also published as a BASIC listing in that May, 1979, issue of SoftSide for the budget-conscious (or the masochistic). One of the things about this era that feels bizarre today even to those of us who were there is how much software was purchased in this excruciatingly non-user-friendly form well into the 1980s. Not only were program listings a staple of the magazines, but bookstore shelves were full of books of them. When we complain about the illogical puzzles and guess-the-verb issues that plague virtually all of these early games, we should remember that it was possible for anyone with modicum of programming knowledge to find answers for herself just using the BASIC LIST command. When Dog Star‘s parser started to frustrate, for example, I hunted down these lines:

30650 VB$(1)="GO":VB$(2)="GET":VB$(3)="LOOK"

30700 VB$(4)="INVEN":VB$(5)="SCORE":VB$(6)="DROP"

30750 VB$(7)="HELP":VB$(8)="SAVE":VB$(9)="LOAD":VB$(10)="QUIT"

30800 VB$(11)="PRESS":VB$(12)="SHOOT":VB$(13)="SAY"

30850 VB$(14)="READ":VB$(15)="EAT":VB$(16)="CSAVE"

30900 VB$(17)="SHOW":VB$(18)="OPEN":VB$(19)="FEED"

30950 VB$(20)="HIT":VB$(21)="KILL"

Right there are all 21 verbs understood by the game. I would submit that source-diving was not only unpreventable but also anticipated, even relied upon, by authors. In this light some of their design choices are perhaps not quite so cruel and bizarre as they initially seem.

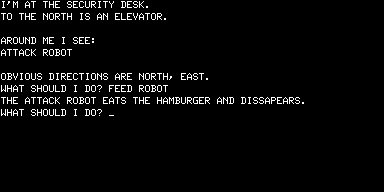

As it happens, I got a little bit too well reacquainted with the tribulations of the BASIC transcriber when I played Dogstar in preparation for this post. In one section of the game there’s a security robot who blocks you from escaping the jail area with Princess Leya. This robot likes McDonald’s hamburgers (in another era I would suspect a marketing deal, but as it is I’ll just have to chalk it up to really bad taste in burgers). Luckily there just happens to be a hamburger lying in the crew’s lounge. Thanks to my BASIC source-diving, I thought I had divined the correct syntax to use to feed it to the robot, but the game obstinately refused to accept it. It turns out that the version of the game I was using had a tiny typo, in this line:

7350 X=22:GOSUB21450IFY<>-1PRINTM6$:GOTO2125

It should have read like this:

7350 X=22:GOSUB21450:IFY<>-1PRINTM6$:GOTO2125

That’s the kind of damage that missing a single colon can do when typing in hundreds of lines of BASIC code by hand. Once corrected I could feed the hungry robot at last.

And yes, the original listing is all crammed together like that. The TRS-80’s BASIC interpreter doesn’t absolutely require spaces to separate the elements of each statement, and spaces use memory — so off they go, along with other niceties such as comments. Readable Dog Star Adventure is not.

Which makes the important role it played rather surprising. Remember all those hobbyists interested in creating their own text adventures? Well, as a competently put-together game conveniently provided to them in print (printers were still a rarity in these days), Dog Star gave them a model to follow in doing just that. (While Scott Adams’s adventures were also coded in BASIC, none was printed in a magazine until 1980, and their interpreter/data-file design made them more difficult to deconstruct than Dog Star‘s admittedly less flexible all-in-one approach.) Lance Micklus himself became increasingly absorbed with his communication products, forming a company of his own later in 1979 to market them, and never coded another text adventure. And yet his fingerprints are all over early text-adventure history, as countless bedroom coders built their own designs from the skeleton he had provided. That, even more so than its hints of actual plotting, is the biggest historical legacy of Dog Star Adventure.

Next time we’ll drop in on Scott Adams again, who like Lance Micklus had a very busy 1979. In the meantime, if you’d like to try Dog Star Adventure I won’t make you type it in from scratch. Here’s a saved state for the MESS TRS-80 Level 2 emulator — and yes, the hamburger-eating robot works correctly in this version.