Scott Adams occupies an odd position in interactive fiction in that he tends to get more love from those outside the active modern community than from those within it. Every year brings one or two fawning interviews with the always obliging Mr. Adams on mainstream or retro-gaming sites. Within the IF community, however, Adams’s works are usually mentioned, if at all, only as historical curiosities, and certainly aren’t accorded even a sliver of the respect given to the Infocom canon, outside of a handful of reactionary voices who declare this lack of respect for Adams’s simplistic but fun games to be symptomatic of the general literary pretensions of the community as a whole that have made the modern text adventure a No Fun Allowed zone. (For a classic and entertaining rant in this vein, see the discussion page of the Adventureland Wikipedia entry.) Further confusing the issue is an unfortunate if blessedly only occasional tendency toward self-aggrandizement on Adams’s own part, such as the FAQ entry on his home page that states he is “credited [by whom?] with starting the entire multi billion dollar a year computer game industry.” “Helping to start” I would be fine with, but as it stands… really, Scott? You singlehandedly started the computer-game industry?

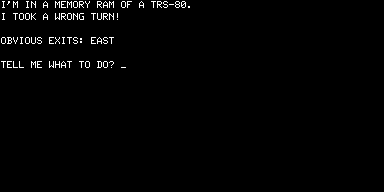

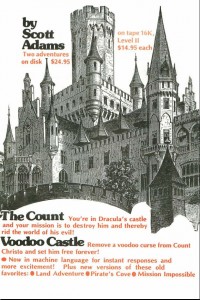

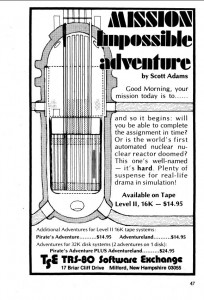

Still, Adams does deserve more credit and respect than he generally receives within community circles for bringing text adventures into homes for the first time and, not incidentally, showing that one could make a pretty good living from the things. His creation of a playable adventure game on a TRS-80 with just 16 K of RAM and a cassette drive was conceptually audacious and technically impressive, and that he did it in the slow, inefficient TRS-80 BASIC just made it even more remarkable. Adams’s greatest failing in the long run was perhaps his inability to make the transition from treasure-hunting text adventures to the more sophisticated storytelling of Infocom’s interactive fiction, as evidenced by his seeming disinterest in improving the core technology of his games beyond gilding these simplistic lillies with graphics and colors. But that’s material for later posts. Today I want to talk about Adams’s initial masterstroke, Adventureland.

Born in 1952, Adams already had extensive professional experience with computers before he created Adventureland in 1978, having majored in the field at the Florida Institute of Technology, worked with computers during a stint in the Navy, and found employment thereafter with Stromberg-Carlson, an early manufacturer of telephone PBX equipment, as a programmer. Adams had also been building and experimenting with microcomputers in his home since 1975, when he built a Sphere 1 from a kit. Beginning with a tic-tac-toe game which “could never lose,” his main activity with these machines had been writing and playing games. Like so many other hackers, he was entranced when Adventure turned up on the computer at his workplace, and, also like so many others, after completing it at last he turned his attention to writing his own. But unlike the others, who did their work on big institutional computers, Adams chose the little TRS-80 as his target platform.

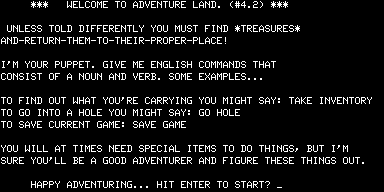

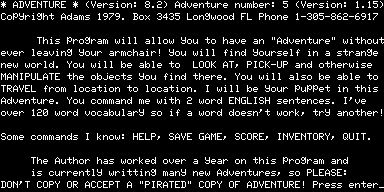

Adams did not set out with grand ideas about bringing interactive narrative to the masses. In standard hacker fashion, he was drawn to the project as an interesting technical challenge in light of the constraints of the TRS-80, and as a chance to work extensively with text, something he hadn’t done previously. As an experienced programmer, Adams shared most hackers’ preference for creating robust, reusable systems and tools in lieu of one-off programs, and so began working not so much on an adventure game as on a reusable adventure implementation system. He thus divided the project into three parts: a database editor of sorts to let him input the data that would make up the virtual world of each game, an interpreter to read in that data and let the player interact with it, and finally the data that made up the game itself.

It’s a remarkable system, but it also should be understood that Adams did not create a full-fledged virtual machine in the sense of Infocom’s later Z-Machine. While the interpreter does indeed read in the details of rooms, objects, etc., much functionality is hard-coded into the BASIC interpreter. The engine, for instance, assumes that gameplay will revolve around gathering a collection of objects (treasures) and dropping them back in a certain location. Any but the most basic modifications to the Adventureland game will also require modifying the code of the interpreter, if only because the name of the game itself and instructions for play are hard-coded there.

It’s really a hybrid system, surprisingly similar in its construction to Adventure itself, which also divided its functionality between the program code and a data file.

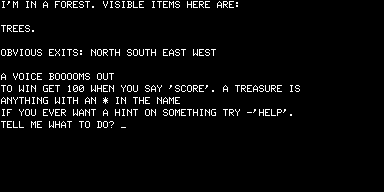

In fact, having just played through the original Adventureland I’m struck by how many similarities it bears to its predecessor. Like Adventure, Adventureland is a plot-less treasure hunt that begins above-ground in a forest.

Adventureland‘s wilderness area is actually larger and more interesting than Adventure‘s, containing a number of puzzles in its own right beyond the obvious one of finding one’s way underground. Its underground complex is, however, vastly smaller, as one would expect given the constraints Adams was working under. This is not entirely to the game’s disadvantage, as Adams’s inability to indulge himself with dozens of empty locations keeps things much more tightly focused and manageable for the player; the obligatory maze, for example, consists of a modest six rooms, a marked and welcome contrast to Adventure‘s monstrosities.

Which is not to say that Adventureland is exactly playable, at least by modern standards. The above-ground areas are filled with the usual non-reversable room connections that make mapping and navigation a non-intuitive pain, redeemed (once again) only by the fact that there are so few locations in all. The logistics of light sources and inventory management are once again a big part of the challenge, and there are heaps of ways to screw up and make the game unwinnable, many unhinted at before they happen. To understand the full cruelty of this, you have to put yourself in the shoes of someone playing the game on an actual TRS-80, where it is only possible to restore a saved position by restarting the game entirely from cassette, a process that takes about 25 minutes. Saving a game, meanwhile, takes over 4 minutes. No wonder Adams could advertise that Adventureland would take weeks or months to complete! What he didn’t mention was that in addition to a TRS-80 it would require the patience of Job…

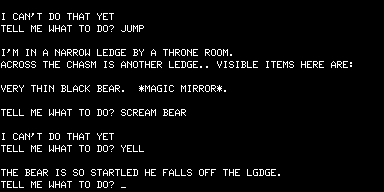

I notice the same dichotomy in Adventureland‘s puzzles that I wrote about with respect to Adventure‘s: most are either very straightforward and commonsensical or unfair to the point of absurdity, with only a few occupying a satisfying middle ground. Also like Adventure, Adventureland is surprisingly progressive in some ways, managing to shoehorn a fair number of hints into its 16 K, but also leaves some of its worst offending puzzles totally unclued. An example is the bear puzzle (a character whose presence is yet another echo of Adventure). He is blocking your way, and can be moved only by the completely unmotivated action of YELLing. Later versions did allow the player to SCREAM at the bear (see Grunion Guy’s review for an hilarious anecdote related to that), but in this original version it was YELLing or nothing.

To make this puzzle even worse, the bear is described as “looking hungry.” This naturally leads the player to want to feed him the honey which she can find elsewhere in the game, which in fact works — except that said honey is also a treasure (?!) she needs to collect to finish the game. Not only is all this supremely cruel, but, just to make it all worse, the false solution actually makes for a much fairer and more satisfying puzzle than the correct one.

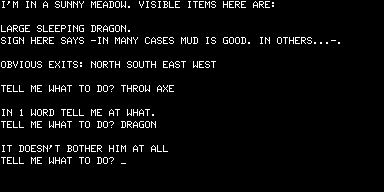

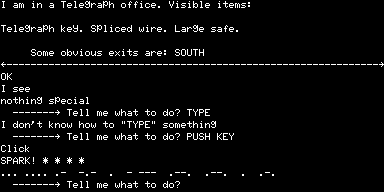

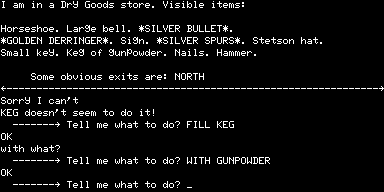

Granted, Adventureland‘s extremely primitive parser and world model do once again perhaps make it difficult to build really challenging puzzles that don’t spill over into unfairness. Its implementation of the THROW verb is quite interesting, as it already shows Adams struggling with the limitations of his two-word parser.

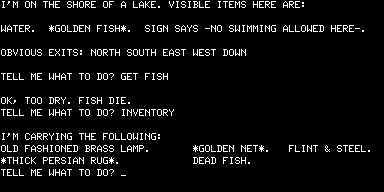

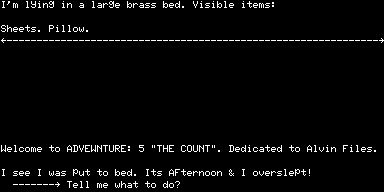

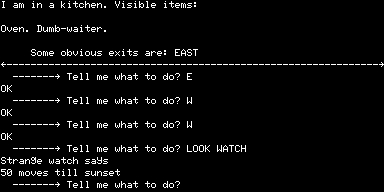

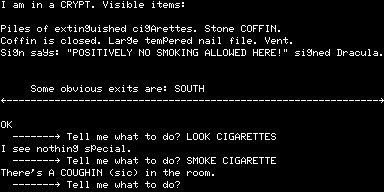

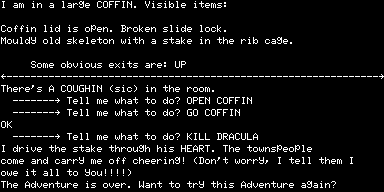

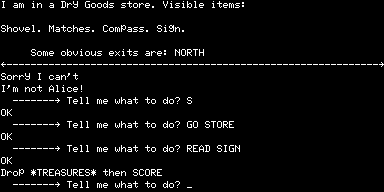

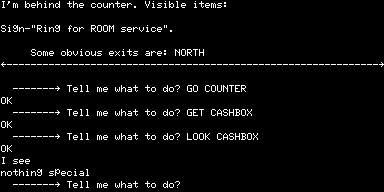

It’s not really fair to judge Adventureland‘s text by literary standards, since every “the” and “a” use precious memory (and thus were often dropped entirely). Still, Adams does at times achieve a sort of minimalist poetry.

He does have some issues with spelling…

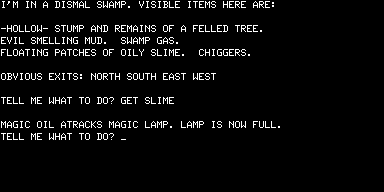

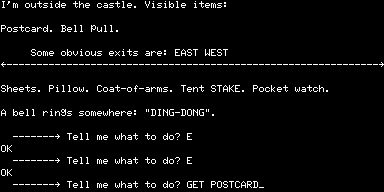

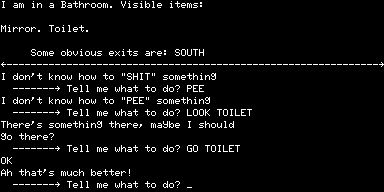

…but there’s a sort of goofy charm about the whole experience…

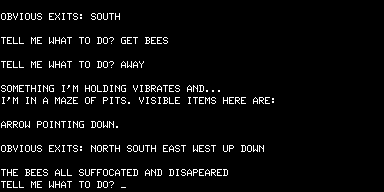

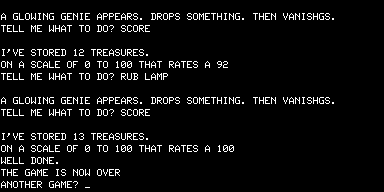

…which finally comes down to this.

And that’s about all there is to say about it, really. There are no advances over the treasure-hunt template laid down by Adventure, but Adventureland is an impressive achievement merely for existing, and even today is still kind of fun in its simple way.

If you’d like to play it for yourself, there are plenty of ways to do so, the most accessible of which is a browser-based version at iFiction. Scott Adams himself hosts downloadable versions on his website. Or, if you want the most authentic experience possible, I have a MESS TRS-80 saved state that will let you play the original BASIC version on its original (virtual) hardware. (See my notes on MESS TRS-80 emulation to get started.)

Next time I’ll talk about Adventureland‘s marketing and reception and the TRS-80 adventure-game craze it started.