Quick: Who first coined the term interactive fiction? And why?

Assuming you had an answer at all, and assuming you’re a loquacious git like me, it may have run something like this:

The term originated, many years after the birth of the genre it describes, in the early 1980s with a company called Infocom. At that time, games of this sort were commonly known as “adventure games” or “text adventures,” the latter to distinguish them from the graphical brand of story-based games which were just beginning to compete with text-based titles in the marketplace of that time. Indeed, both terms are commonly used to this day, although they generally connote a rather “old-school” form of the genre that places most of its emphasis on the more gamelike, as opposed to literary, potentials of the form. Infocom decided that interactive fiction was a term which more accurately described their goal of creating a viable new literary form, and following that company’s demise the term was appropriated by a modern community of text-based storytellers who in many ways see themselves as heirs to Infocom’s legacy.

That, anyway, is what I wrote five years ago in my history of interactive fiction. I still think it describes pretty accurately Infocom’s motivation for replacing the term text adventure with IF, but it’s inaccurate in one important sense: the term did not actually originate with Infocom. It was rather the creation of a fellow named Robert Lafore, who founded a company under that name in 1979 and published software from 1980 to 1982 through Scott Adams’s Adventure International. By the time that Lafore came to AI, he already had three titles in the line ready to go. Local Call for Death and Two Heads of the Coin are mystery stories with an obvious debt to Dorothy L. Sayers’s Lord Peter Wimsey and Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes respectively, while Six Micro-Stories presents six brief vignettes in a variety of settings and genres. Over the next year or so he wrote two more: His Majesty’s Ship Impetuous, in the style of C.S. Forester’s Horatio Hornblower novels; and Dragons of Hong Kong, in the spirit of Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu series of oriental mysteries.

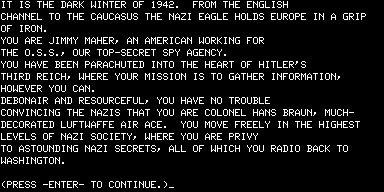

To understand what Lafore’s concept of IF is and how it works, let’s begin with some promotional copy. After asking us to “step into a new dimension in literature,” Adventure International’s advertisement for the line continues:

Traditionally, literature has been a one-way medium. The information flow was from the novel to the reader, period. Interactive fiction changes this by permitting the reader to participate in the story itself.

The computer sets the scene with a fictional situation, which you read from the terminal. Then you become a character in the story: when it’s you’re turn to speak, you type in your response. The dialog of the other characters, and even the plot, will depend on what you say.

Wow. No previous computer “game” had dared to compare its story to that of a novel. Just the text above, divorced from the actual program it describes, demonstrates a real vision of the future of ludic narrative.

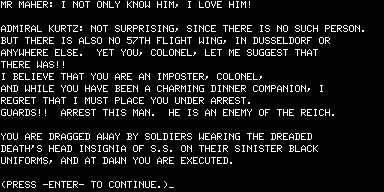

But as anyone who’s had experience with early computer-game ad copy knows, the reality often doesn’t match the rhetoric, with the latter often seeming aspirational rather than descriptive, corresponding more with the game the authors would like to have created than with the technical constraints of 8-bit processors and minuscule memories. Here’s a complete play-through of the first of the vignettes of Six Micro-Stories, “The Fatal Admission”:

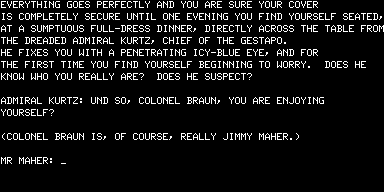

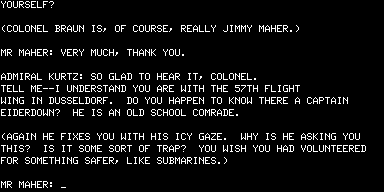

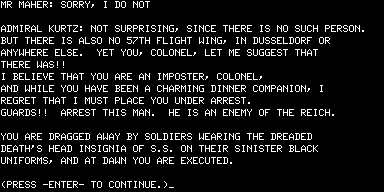

Admittedly, this is not Lafore’s finest hour, so let’s try to be gentle. Let’s leave aside the fact that an admiral could only have been in the Kriegsmarine, not the Gestapo, as well as Lafore’s obvious cluelessness about German. Let’s also leave aside the illogicality of the question on which the story turns. (If I’ve been actively impersonating Colonel Braun for so long, how could I not know what flight wing I am with?) And let’s leave aside the unfair, learning-by-death aspect of the whole experience. I just want to get down to how the program works right now.

As will probably surprise no one, the program is not parsing the player’s responses in any meaningful sense, but rather doing simple pattern matching on the player’s input, somewhat in the style of Eliza but without even that program’s sophistication. Given this, it’s inevitably very easy to trip the program up, intentionally or unintentionally. Consider the following response to the admiral’s question about Captain Eiderdown:

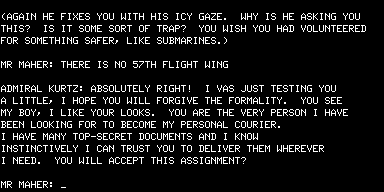

What’s happened here is that the program has found the “not” in the player’s input and thrown out everything else, assuming the sentence to be a negative answer. This is not an isolated incident. Let’s try yet again to answer the trick question about the 57th Air Wing correctly and stay alive.

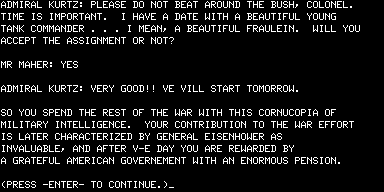

Cool! Now we can accept our new assignment and learn even more juicy Nazi secrets.

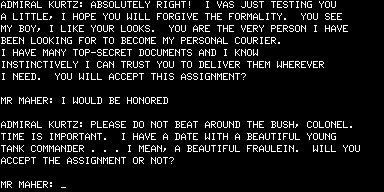

Woops. The program has failed to understand us entirely that time, which is at least better than a misunderstanding I suppose.

Obviously simple answers are the best answers.

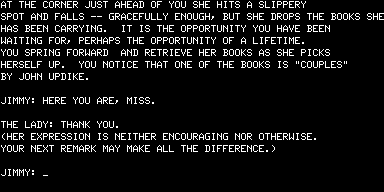

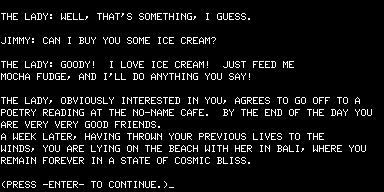

Various vignettes in Six Micro-Stories do various things with the entered text. Perhaps the most complex and computationally interesting entry in the collection is called “Encounter in the Park,” in which you must try to get a date from a young lady you meet by chance in the park. It plays like a goal-directed version of Eliza, albeit a very primitive one. In case the connection is not obvious, the love interest’s name is even, you guessed it, Eliza.

The ultimate solution is ice cream; the mere mention of it causes Eliza to shed her sophisticated Updike-reading trappings and collapse into schoolgirl submissiveness. (The implications of this behavior in a paternalistic society like ours we will leave for the gender-studies experts.)

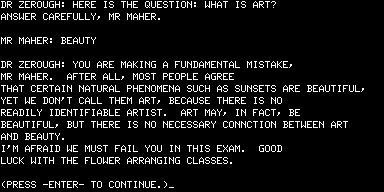

Another vignette is little more than a multiple-choice quiz on the age-old question of the definition of art.

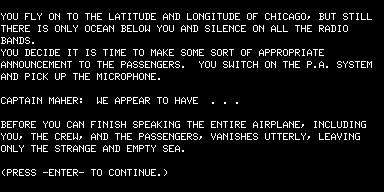

And then there’s this nihilistic little number, in which nothing you type makes any difference whatsoever:

Lafore was either in a pissy mood when he wrote that one or homing in on some existential truth the rest of us can’t bear to face — take your choice.

But these are exceptions. When we get past the parser to look at the player’s actual options (thank God for BASIC!), we find that the remainder of the vignettes, as well as all of the vastly more compelling full-length stories, are really multiple-choice narratives, in which the player can choose from (usually) two or (occasionally) as many as three, four, or five options in a series of hard-coded decision points. In other words, these are really choose-your-own-adventure stories / hypertext narratives / choice-based narratives (choose your term). They are much closer to the Choose Your Own Adventure books that were just beginning to flood bookstores in 1980 than they are to the text adventures of Scott Adams or, indeed, to the interactive fiction that Infocom would soon be publishing. It’s just that their real nature is obscured by the frustrating Eliza-esque “parser” which adds an extra layer of guesswork to each decision. Sure, there are arguments to be made for the parser here. Theoretically at least, allowing the player to make decisions “in her own words” could help to draw her into the story and the role she plays there. In practice, though, the opportunities for miscommunication are so great that they outweigh any possible positives.

In a demonstration of just how ridiculously far I’m willing to go to prove a point, I reimplemented what I consider to be the most satisfying of the longer stories, His Majesty’s Ship Impetuous, using the ChoiceScript system. (Well, okay, I did want to try out ChoiceScript as well, and this project made a good excuse…) If you care to play it, you’ll find that it’s a much more complete and satisfying effort than those I’ve highlighted above, if not totally free of some of their design problems, in that getting an optimal outcome requires a bit of learning from death. Still, Lafore’s writing is sharp and well suited to the genre, and the story as a whole is carefully thought through; this represents easily the most competently crafted fiction yet to grace a computer screen in 1980. Its good qualities come through much better shorn of the Eliza trappings. Indeed, it’s much more interesting to consider in this light, because choice-based narratives had not yet made their way to the computer before Lafore set to work.

I don’t want to try to formulate a detailed theory of choice-based narrative design here, particularly because Sam Kabo Ashwell is gradually doing exactly that via his amazing series of analyses of various works in the form — a series to which nothing I say here can bear comparison. I do, however, want to note that parser-based and choice-based narratives are very different from one another, yet are constantly confused; Lafore was perhaps the first to make this mistake, but he was hardly the last. For example, the Usenet newsgroup that was the center of IF discussion for many years, rec.arts.int-fiction, was originally founded by hypertext aficionados, only to be invaded and co-opted by the text-adventure people. And even today, the very interesting-looking Varytale project bills itself as “interactive fiction.” Choice of Games doesn’t go that far, but does actively encourage authors to submit their ChoiceScript games to IF competitions, something that doesn’t really bother me but that perhaps does bring two sets of expectations into a collision that doesn’t always serve either so well.

The primary formal difference here is in the granularity of the choices offered. Parser-based IF deals in micro-actions: picking up and dropping objects, moving from one concretely bounded space to another, fiddling with that lock in exactly the right way to get that door open. Choice-based narratives at their best deal in large, defining decisions: going to war with Eastasia or with Eurasia, trying to find your way back to the Cave of Time or giving up. Even when the choices presented are seemingly of an IF-like granularity, such as whether to take the left or the right branch in that dungeon you’re exploring, they should turn out to be of real consequence. A single choice in a choice-based narrative can encompass thousands of turns in a parser-based work of IF — or easily an entire game. When authors combine a choice-based structure with an IF-like level of granularity, the results are almost always unfortunate; see for example 2009 IF Competition entry Trap Cave, which attempted to shoehorn an Adventure-style cave crawl into a choice-based format, or Ashwell’s analysis of a Fighting Fantasy gamebook. A choice-based narrative needs to give its player real narrative agency — at the big, defining level of choosing where the plot goes — to be successful. Parser-based IF does not; it can let the player happily busy herself with the details while guiding her firmly along an essentially railroaded plot arc.

Given that they can tell such large swathes of story at a hop, we might be tempted to conclude that choice-based games allow deeper, richer stories. In a way that’s true, especially in the context of 1980; it would have been impossible to pack even 10% of the story of His Majesty’s Ship Impetuous into a Scott Adams-style game. It’s also true that choice-based narratives are generally not so much about challenging their players with puzzles or tactical dilemmas as they are about the “pure” experience of story. A contemporary reviewer of His Majesty’s Ship Impetuous writing in SoftSide magazine, Dave Albert, very perceptively picked up on these qualities and in the process summarized the joys of a choice-based narrative as well as some of the frustrations of Lafore’s early implementation of same:

Lafore has tried to write an open-ended story with several possible endings, and he has tried to structure it so that the reader/player is unaware of the import of the decisions made. Where in previous stories the player is allowed to ask any question that comes to mind (with often incongruous and confusing results), in Impetuous yes or no decisions are presented. There is no way to work around this structure, and it is greatly to the benefit of the program that such is the case. There is no puzzle to solve, only a story to develop. The end goal is to survive and the decisions that you make will dictate whether you do or not. However, you cannot decipher what is the proper course of action that will guarantee your success. There are enough critical points (decisions) in the program to make you uncertain of your actions after several games. This greatly enhances the value of the program.

I wouldn’t frame all the specific design choices in Impetuous quite so positively as Albert, but I think the larger points stand. Choice-based works encourage the player to view them from on-high, like a puppet master manipulating not just her character but the strings of the plot itself; note that Impetuous is written in the third-person past tense. The player manipulates the story, but she does not always feel herself to be in the story. Some more recent choice-based works have even divorced the player entirely from any set in-world avatar. Parser-based IF, however, excels at putting you right there, immersed in the virtual reality you are exploring. Both approaches are valid for telling different kinds of stories, creating different kinds of experiences, and both can go horribly awry. Too many choice-based works leave their player feeling so removed from the action that she ceases to care at all (this, I must admit, is my typical reaction when playing even the modern ChoiceScript games, and the main reason my heart belongs firmly to the parser-based camp); too many parser-based works, especially early ones, become so fiddly that they only frustrate.

Minus the parser frustrations, Impetuous is a fairly successful piece of work, written at an appropriate level of abstraction for the choice-based form. If many of its choices are ultimately false ones, having no real effect on the plot, it disguises this well enough that the player does not really realize it, at least on the first play-through, while enough choices do matter to keep the player interested. Best of all, and most surprisingly when we consider the structure of, say, the early Choose Your Own Adventure books, there are no arbitrary, context-less choices (will you go right or left in this dungeon?) and no choices that lead out of the blue to death. Some of its ethical positions are debatable, such as the way it favors plunging headlong into battle versus a more considered approach, but perhaps that’s par for the course given its genre.

One of the amusing and/or disconcerting aspects of writing this blog has been that I sometimes find myself honoring pioneers who have no idea they are pioneers. Lafore traded in his entertainment-software business after writing Dragons of Hong Kong for a long, successful, and still ongoing career as an author of technical books. I’m going to guess that he has no idea that the term he invented all those years ago remains vital while the works to which he applied it have been largely forgotten.

By way of remedying that at least a little bit, do give my implementation of His Majesty’s Ship Impetuous a shot. I think it works pretty well in this format, and is more entertaining and well-written than it has a right to be. (Credit goes to Lafore for that, of course.) And if you’d like to play the originals of either Six Micro-Stories or His Majesty’s Ship Impetuous, you can do that too.

1. Download my Robert Lafore starter pack.

2. Start the sdltrs emulator.

3. Press F7, then load “newdos.dsk” in floppy drive 0 and either “microstories.dsk” or “impetuous.dsk” into floppy drive 1.

4. Reboot the emulator by pressing F10.

5. At the DOS prompt, type BASIC.

6. Type LOAD “STORY:1″ for Six Micro-Stories; LOAD “STORY1:1” for His Majesty’s Ship Impetuous.

7. Type RUN.

Next time I want to have a look at the evolving state of the computer industry in 1980 — and begin to execute a (hopefully) deft platform switch.

Victor Gijsbers

September 1, 2011 at 10:21 am

Very interesting, and I enjoyed the game. (You might want to throw a spell checker over it, though.) At least in this ChoiceScript format, it feels quite modern; much more modern, I would guess, than any Scott Adams could ever feel, even if it were ported to a system with capital letters and a multi-word parser.

matt w

September 1, 2011 at 5:51 pm

Yes, very enjoyable game. I actually quite like the flavor choices; they remind me of the graphic game Balloon Diaspora which is about 25% coupon-gathering and 75% flavor choices, in a way that makes it clear that the flavor is important. Here you have a choice of how to treat, say, Millby, and even if it doesn’t affect the ending it allows you to do some role-playing. (Not to mention that it helps disguise the choices that do matter.)

Mostly off-topic, I think I’ve figured out how to use a free-form keyword parsing thing: You’re in, say, rural Quebec, you barely speak French, and the NPCs don’t speak English at all. So if you type in “Under no circumstances should you hand me the bucket” the response is something like, “You wave your hands around and say ‘Under no circumstances should vous hand moi le seau.’ The concierge, delightedly recognizing the word ‘seau,’ hands you the bucket.” It doesn’t pretend to understand any more than it does, and I think it nicely captures the experience of getting the opposite of what you want because you can only remember one word in the language you’re speaking. Of course the only French words the PC can remember are the ones that turn out to be plot-crucial.

Jimmy Maher

September 2, 2011 at 8:50 am

Ha… yes, that might just work. Very clever.

Harry McCracken

January 22, 2013 at 5:48 am

A very enjoyable blog post. I probably understood the limitations of these games when I played them upon their original release, but I REALLY liked them — in part because they had more style and humor than most TRS-80 games.

Mike Taylor

October 16, 2017 at 12:56 pm

Interesting. I played through _Local Call for Murder_ a little while back, having been intrigued by Jason Dyer’s much more positive take. I had a much more positive experience than you seem to have done — possibly because you were treating the games a puzzles to be solved whereas I relaxed into the role-playing aspect. To my mind, this is many years ahead of its time. You just have to think of it the way Weizenbaum’s secretary thought of ELIZA rather than the way he did.

Mike Taylor

October 16, 2017 at 1:20 pm

Playing your reimplementation of Impetuous. It’s extremely impressive — almost impossibe to believe it’s from 1980. I sniggered at the names of the French warships, and laughed out loud at those of the English.

And I found the closing passage (“Even today his brave attack on the combined fleets of France and Spain is read about by British schoolchildren …”) genuinely moving. It just shows the value of having a writer write IF.

One bug I’ve come across. I pardoned young Fallon (with no apparent consequence), but later when we returned to Fallon bay I was told that he would be far inland by now — as though I’d told him to run rather than pardoning him.

Jimmy Maher

October 17, 2017 at 8:23 am

I think that bug, if such it be, was present in the original BASIC as well. Perhaps due to memory limitations…

asdas

August 22, 2018 at 2:14 am

Typo:

genre, and story as a whole → genre, and the story as a whole

asda

August 22, 2018 at 2:21 am

Typo:

you can do that do too. → you can do that too.

Jimmy Maher

August 22, 2018 at 8:21 am

Thanks for these!

Will Moczarski

June 23, 2019 at 9:02 pm

miniscule -> minuscule

Will Moczarski

June 23, 2019 at 9:14 pm

much more complete and satisfying efforts -> effort

Jimmy Maher

June 24, 2019 at 7:42 am

Thanks!

Jeff Nyman

May 9, 2021 at 1:14 pm

Fantastic article!

“Just the text above, divorced from the actual program it describes, demonstrates a real vision of the future of ludic narrative.”

Yes … but does it? I find that part quoted in the promotional material interesting when you consider it in light the text in the manual for Temple of Apshai:

“Role-playing games are not so much ‘played’ as they are experienced. … As you set off in quest of fame and fortune in company with those other player/characters, you are both a character in and a reader of an epic you are helping to create. Your character does whatever you wish him to do, subject to his human (or near-human) capabilities and the vagaries of chance.”

What’s mainly missing from the latter is any reference to an association with the novel. Yet you could certainly read into it just that. After all, “Dungeons & Dragons” was a way to participate in fantasy stories that, previously, you might have just read.

So I think you make a really interesting point here about the ad copy often “seeming aspirational rather than descriptive.” But notice how that’s something more peculiar to the text adventure than it was of the CRPG. So it’s perhaps interesting that even with the “technical constraints of 8-bit processors and minuscule memories”, people were able to craft stories — even if only in their heads — with CRPGs. This was instead of having to “live through” some crafted story.

This is fascinating to me because it clearly shows the very different styles of play and schools of thought that came to exist around these two concepts.

I also think what’s quite a bit more interesting here is that ELIZA-like aspect. Clearly the conversation interface of ELIZA could been seen as a forerunner to the text adventure, where the conversational bits became commands. But here we see an attempt to meld the two. This seems an interesting evolutionary path that wasn’t really taken. One game I remember that tried something similar was “Metropolis” from 1987 (https://www.old-games.com/download/1450/metropolis).

So what seems very interesting here — besides the first use of “interactive fiction” — is this idea of a particular evolutionary path towards understanding player input.

Jeff Nyman

May 9, 2021 at 1:18 pm

“… we find that the remainder of the vignettes, as well as all of the vastly more compelling full-length stories, are really multiple-choice narratives, in which the player can choose from (usually) two or (occasionally) as many as three, four, or five options in a series of hard-coded decision points.”

Yep, and this, to me, is what shows that text adventures have always really been nothing more than what we now label as CYOA games, which certainly correlates with the “Choose Your Own Adventure” book. You are choosing your own adventure in the books — just as in the games — but these are still nowhere near how people perceive choosing their own adventure in even the most limited of CRPGs. I personally feel this is always why text adventures were slated to be left in the dust, regardless of graphics or other trappings.

Historically I think this is borne out by the fact that there really has been no great evolution in text adventures at all, whereas CRPGs have evolved along multiple paths, which allowed them to be incorporated, in whole or in part, to other game genres.

When you break down a text adventure to its fundamental bits, it’s really just a series of gates: “Have I done the right thing with the right object at the right time?” Which really breaks down to: “Have I followed the particular choice path that will work?” Yes, it’s obscured a bit by the micro-actions you have to take, but it’s no less there. So when I read this:

“It’s just that their real nature is obscured by the frustrating Eliza-esque ‘parser’ which adds an extra layer of guesswork to each decision.”

And yet that extra layer of guesswork is what might actually make them interesting. (After all, it’s what made ELIZA very interesting to people, such that it actually engaged emotions.) Yet, I agree, these games are still fundamentally text adventures and thus that extra layer of guesswork really offers no reward except to slow down the experience.

But I think what these games were showing is that this is really what the text adventure fundamentally is. It really is just ELIZA glossed up a bit. It really is just ELIZA but with more focus on specific commands leading to specific results. It’s a very gated and gating experience.

As you say (and kudos for the fascinating ChoiceScript experiment): “Its good qualities come through much better shorn of the Eliza trappings.”

But it absolutely shows, I think, the connective tissue: text adventures can be seen to stem from an ELIZA like interface but with modified input options. And text adventures are really nothing more than a “choose your own adventure” book rendered on the computer, just as CRPGs rendered a tabletop game on computer.

Jeff Nyman

May 9, 2021 at 1:23 pm

“I do, however, want to note that parser-based and choice-based narratives are very different from one another, yet are constantly confused.”

I respect the viewpoint but I actually think they are extremely close to each other and that’s why they are “constantly” confused. If something is “constantly” confused, there might be good reasons for that. We tend to assume it’s just people getting wrong. But maybe they’re getting it exactly right.

In reality, I don’t they are being confused at all. I think people are simply seeing through the concept as presented to what the base mechanics actually are.

“The primary formal difference here is in the granularity of the choices offered. Parser-based IF deals in micro-actions. … Choice-based narratives at their best deal in large, defining decisions.”

Agreed! But when you break down the former, you see that it leads to the latter. The micro-actions lead up to the macro-action: defeat the main enemy, save the princess, find all the treasure, etc. And the latter, when broken down, is shown to be the former: all large, defining decisions could be broken down into a series of micro-actions. Which you basically indicate in this post. The type of experience of different, of course, but I think intuitively gamers and readers understand that what’s being done is the exact same thing.

So: “When authors combine a choice-based structure with an IF-like level of granularity, the results are almost always unfortunate…”

That is an extremely interesting observation and I think it becomes more explicable when you realize that what is being combined are really of the same modality. So, yes, perhaps counter-intuitively for some, they really don’t fit together.

Contrast that with, say, “Wasteland” which had its paragraph book that you read at certain points when the game told you to, giving you some text or dialogue. That managed to fit together fairly well. And, of course, in such a game you always have those multiple choice options of retreat, attack, try to talk to, etc. Less options than a text adventure — or is it? When you view the text adventure as really a CYOA at heart, I think the distinction between adventuring cultures becomes really clear.

So we’re once again left with the defining experience of the player/reader/gamer. And CRPGs, I think, have shown that this experience lends itself more to the role playing aspect which has led to more of the story telling (and narrative arc) aspect which shows us why this format has been the one that became incorporated into so many genres of game. (Even though the choice bits do also live on, such as the dialog wheels or menus in games like “Mass Effect” and “Dragon Age”.)

Just realized I wrote three replies to one article here! But kudos on this series of articles from the CRPGs up to here. I think it shows a fascinating line of thought regarding how things evolved.