Mystery House had been an experiment, done on the fly and on the cheap, to see whether there was enough money to be made in computer games to justify jumping in with both feet. Within days of the game’s release, the answer was plainly a resounding yes, and Ken and Roberta started working on systematizing the process and beginning a whole line of On-Line Systems “Hi-Res Adventures.” As Roberta sketched out a design — this time a more typical fantasy adventure, albeit one more inspired by fairy tales than Tolkien — Ken worked like mad to pull together a set of tools capable of implementing not just the next adventure but many more to come. Hackers love their tools, after all, and whatever his loyalty (or lack thereof) to the hacker ethic of elegant software as an idealistic end unto itself, Ken was no exception in this regard. Like Scott Adams before him, he coded a reusable adventuring engine, keeping the data that made up the new adventure separate from the interpreter that made it come alive — a move that would pay off in spades soon enough, when On-Line Systems began expanding its reach beyond the Apple II platform.

But most of all he devoted his attention to the thing that had made Mystery House stand out from its peers, its graphics. He and Roberta had been able to get away with the crude black-and-white sketches in that game thanks to the novelty factor, but the next game had to look better. He therefore set to work implementing a color drawing program to replace the clunky old VersaWriter-based system that had sufficed for Mystery House.

As I’ve mentioned before in this blog, before designing the Apple II or even Apple I Steve Wozniak had designed the Breakout arcade game for Atari. That experience came to shape the Apple II, for Woz, in his usual endearingly quirky way, took the ability to play an acceptable game of Breakout as a sort of baseline expectation for his new machine. This requirement was the main reason that the Apple II’s unique hi-res mode came to exist at all. Woz even made sure the machine’s BASIC had commands enough to make it possible to implement Breakout entirely using only BASIC statements. And Woz’s Breakout fixation was also the reason that a pair of paddle controllers shipped with every single Apple II and Apple II Plus — after all, they were what the arcade Breakout used.

Given the fact that every Apple II owner automatically had a pair, paddles became the standard method of control for early arcade-style games on the platform, limiting as they could sometimes be. Joysticks remained for years a somewhat pricy and unusual novelty — to such an extent, in fact, that Ken designed his new drawing system to use paddles rather than a seemingly more appropriate joystick. With one paddle controlling the X-coordinate and one the Y, the user could (with a bit of practice) draw and fill pictures right on the screen. Perhaps more usefully than its supremely awkward free-hand modes, Ken’s software also functioned as a structured drawing system of sorts, letting the user connect points on the screen with straight lines. One could even draw box sides in a similar fashion. Combined with another program, also of Ken’s devising, that let one draw and edit using Apple’s official graphics tablet, Ken and Roberta now had a downright state-of-the-art graphics workstation by the standards of 1980. Even better, they also had a couple more products to sell; Paddle Graphics and Tablet Graphics were hanging in stores in the usual Ziploc bags even before the game they had been written to create hit the scene.

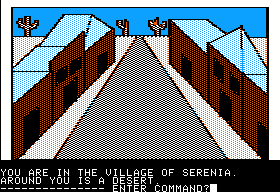

Said game appeared in September, a scant four months after Mystery House, under the name The Wizard and the Princess. In light of all Ken’s other activities and the technical challenges he and Roberta had to overcome to create it, that time scale is almost unbelievable, but there you are. Those who plunked down their $32.95 and rushed home to boot the disk were greeted by this:

Your reaction to the screenshot above may just be determined by how long you’ve been following this blog. If you’re a relative newcomer, you’re probably pretty nonplussed. If you’ve been reading since the beginning, though, following me through the black-and-white worlds of teletype text and the TRS-80, the monochrome utilitarianism of Temple of Apshai, and the not-quite-monochrome (but don’t you wish they were in lieu of those ugly splats of color?) naivete of Mystery House‘s pictures, you just might, if you’ve taken our time traveling to heart, feel some shadow of the awe that all those Apple II owners felt in 1980. This was stunning, stunning stuff, easily the most impressive graphical display that had yet graced an Apple. And this was Ken’s philosophy that a game should have “wow” factor, should sell itself if someone just booted it up inside a computer store, put into perfect practice.

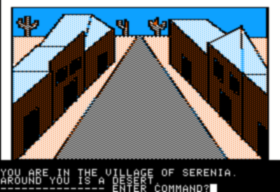

If you’re not feeling it so much, don’t feel too bad. Actually, what you see above is not quite what players were seeing on their monitors in 1980. All of those tiny pinpricks of color stand out distinctly on our too-perfect modern digital displays. On a real Apple II monitor with its analog circuitry, however, those individual pixels tended to blend together, producing something that looked more like this:

In fact, Ken was relying on exactly this phenomenon to produce the illusion of many more onscreen colors than the Apple II’s official 6. It’s a technique known as dithering. In the sales literature for The Wizard and the Princess, as well as those paint programs used to help create it, On-Line Systems claimed that Ken’s dithering technique effectively increased the number of possible colors from 6 to 21. It’s an effect that is lost on us when we play through emulation — and therein lies the lesson that, while emulation is important in its own right, sometimes we need real hardware to fully appreciate the software artifacts we study.

So, as a demonstration of graphical technology The Wizard and the Princess was truly a stunner. When we look at it as a game, the situation is, as with Mystery House, a bit more… complicated. We’ll get into that next time.