It’s 1980, and we just bought The Wizard and the Princess. Shall we play?

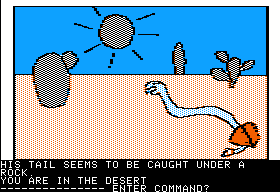

After the game boots, we find ourselves in the village of Serenia. We are about to set off to rescue Princess Priscilla from the “great and dreadful wizard” Harlin. And so we stride boldly forth, armed with wits and bravery, ready to conquer… the tedious 15-room desert maze that begins immediately outside of town. An hour or so of careful mapping later, we have determined that our path out of this monstrosity is blocked by a snake that refuses to let us pass. Naturally, being the destructive adventuring type that we are, we start casting about for some way to kill it. Perhaps one of those rocks that are scattered throughout the maze. So we try to gather one up… only to be killed by the scorpion that lurks underneath. After trying every nonsensical thing we can think of, we finally call up old Ken and Roberta themselves for a hint, whereupon we learn that we were on the right track to start with. It’s just that there is only one rock in the maze that doesn’t shelter a scorpion, and that we can therefore pick up without getting killed. Since there is absolutely no way to identify this rock, we get to spend the next hour dying and restarting until we find the right one. If we’re not so excited about watching those pretty but monotonously similar desert pictures draw themselves in slowly again and again by this point, perhaps that’s understandable.

In 1993, when the modern interactive-fiction community that still persists today was just getting off the ground, Graham Nelson wrote up a “Player’s Bill of Rights” to begin to codify good adventure-game design practice. Just in its first few turns of play The Wizard and the Princess has managed to violate 4 of 17 rights: “Not to be killed without warning”; “To be able to win without experience of past lives”; “Not to need to do boring things for the sake of it”; and “Not to be given too many red herrings.” In light of that achievement, I started wondering how many in total the game could manage to trample over. Let’s see how we go…

Not to need to do unlikely things. Not long after bashing one snake with a rock, we encounter another pinned beneath a rock (snakes and rocks obviously figure prominently in this stage of the game). This new snake is presumably as dangerous as the last, and judging from our handling of the first one we aren’t exactly fond of our scaled cousins — but that doesn’t stop us from kindly freeing the snake from his predicament. Turns out he was king of the snakes, and even has a magic word to give us in thanks! (What I’d like to know is just what sort of reptilian royalty manages to get itself stuck under a rock in the first place. Are the snake proletariat classes in revolt?)

Not to depend much on luck. Our encounter with the kindly snake was an anomaly. Pretty soon there’s another chasing us around wanting to kill us. We have to find a stick in another location in the desert, then hit the snake on the head with it to drive it away (an image I find strangely hilarious). If the snake should (randomly) appear at the wrong place or the wrong moment, though, we won’t have time to do that — and it’s curtains for us through no fault of our own.

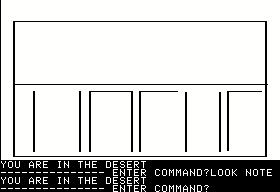

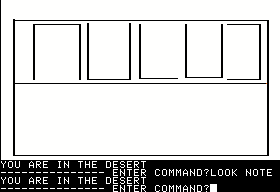

To have a decent parser. Further on in this endless desert, we discover a couple of notes just lying about, as is common in deserts everywhere. Both are known simply as “note”; the parser apparently randomly selects one when we try to interact with a “note” while both are in our current location. The only way to consistently work with one or the other is to keep each in a separate location entirely. Stuff like this makes me want to write this right in all capital letters, like this: TO HAVE A DECENT PARSER, DAMN IT!

Not to be given horribly unclear hints. Yet further on in the desert we come to a deep, uncrossable chasm. We have to enter the magic word “HOCUS,” whereupon a bridge materializes. I’m not exactly sure how the player is expected to divine this word, but my best guess is that one is supposed to somehow extract it from the contents of one or both of those notes I just told you about, and which are shown above. The one on the left kind of looks like “HOCUS,” doesn’t it? Maybe, if you squint just right? Of course, even if we make that intuitive leap we still have to go around typing “HOCUS” literally everywhere, until something finally happens. But by now the game has already pretty thoroughly ground our right to be exempt from “boring things” into dust with its best jackbooted thugs, hasn’t it?

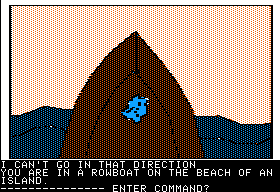

To have a good reason why something is impossible. We escape the mainland to a small island via a rowboat we find handily lying about. Having dealt with the usual inanities there, there comes a time when we are ready to leave. It might seem natural to use the rowboat that brought us there to travel onward, but that’s impossible. Why? I don’t know — the game just tells us, “I can’t go in that direction.”

To be allowed reasonable synonyms. We are actually expected to travel on using a potion of flight. (We can only figure out exactly where on the island to use it by drinking it over and over again, once in every room, restoring after each experiment. But by now a sort of Stockholm-Syndrome-esque complicity has set in, and we just accept that and go to work with a sigh.) The perfectly natural noun “potion” is not accepted here. We can only “DRINK VIAL” (an interesting thought…) or “DRINK LIQUID.”

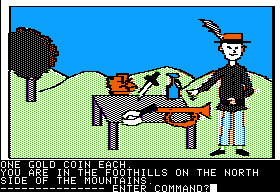

To be able to win without knowledge of future events. Moving on, we encounter a peddler offering what appear to be a pair of boots, a dagger, a wine jug, a magnifying glass, and a trumpet for sale. We have just one gold coin, and no idea which of these items we’re likely to need. So we have to save the game and start buying them one by one, each time moving on into the game looking for a puzzle we can solve with that item or the dead end that indicates we must have chosen wrong. And no, the peddler doesn’t have a trade-in policy.

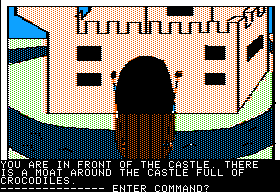

To be able to understand a problem once it is solved. At long last we come to the wizard’s castle. We’re confronted there by a closed drawbridge. It turns out that the correct solution to this problem is to blow the trumpet we bought from the peddler — there’s that question answered, anyway. I recognize some allusion to a returning knight blowing his horn to alert the castle of his return. But why should this work for us, the wizard’s enemy? Shouldn’t blowing the trumpet rather bring a fireball down on our head? And who opens the drawbridge? Certainly no doorman greets us inside. Or is it a magic trumpet? But if it’s a magic trumpet that gives one access to his stronghold, why the hell did the wizard give it to the peddler? Or did he lose it, and the peddler just sort of found it by the roadside? The world will never know…

Inside the castle, our showdown with the wizard is one of the most anticlimactic finales ever. In lieu of the wizard himself, Roberta presents us with yet another enormous, empty maze. (At least the game, in ending as it began, manages a sort of structural unity.) We never even see him as a wizard, only as a bird he has for some reason chosen to transform himself into. Luckily we have a magic ring that briefly turns us into a cat — if we mess around with it long enough to figure out we need to rub it, not wear it, that is — and that’s that.

And Nelson’s other player’s rights? “Not to have the game closed off without warning,” “Not to have to type exactly the right verb,” and “To know how the game is getting on” are violated so thoroughly and consistently by the game that there isn’t much point in belaboring them.

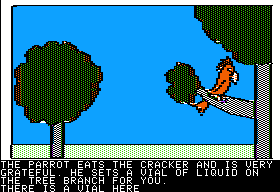

Not to need to be American to understand hints. This right was born from Nelson’s loathing for one particular puzzle, the infamous baseball diamond of Infocom’s Zork II (about which more when we get there); hence its unusual specificity. I think it can be better reframed as a prohibition against requiring too much culturally specific knowledge of any stripe. The Wizard and the Princess manages to not offend too deeply here, although there is one point where, having escaped from the mainland to a tropical island via a rowboat we found handily lying about, we have to give the cracker we found in the desert (amazing what turns up in the desert, isn’t it?) to a parrot. While not exclusively American, I believe the old “Polly want a cracker” meme is confined to the English-speaking world.

To be given reasonable freedom of action. Within the boundaries of the primitive parser and world model, the player does have reasonable freedom. It’s mostly freedom to hang himself, but still… freedom isn’t free, or something like that.

Without these last two, then, we are left with a solid 15 out of 17 potential violations. Not quite a perfect run, but a damn good effort.

So, having had my bit of fun, it’s time to say a few things. Some might regard it as a poor sport to so thoroughly rip apart one particular offender in an early adventure-game scene that was absolutely full of them. Roberta was after all, like other early designers, working without a net, with no received wisdom about good design practice, and with extremely primitive technology to boot. It’s a valid enough charge. The only defense I can offer, which is not really a defense at all, is that I feel particularly unforgiving toward Roberta because she just kept on doing this sort of stuff throughout her almost 20-year career, long after excuses about received design wisdom and technology ceased to hold water. And, having spent so much time with old-school adventures over the past six months, perhaps there did come a point where I just had to vent. Certainly this has been a complete violation of one of my normal policies for this blog, to always try to see the works I analyze in the context of their times. Maybe it’s a good idea to get back to that now, and to ask just why players accepted this stuff — to most outward appearances happily — in 1980, as well as what led designers to commit such violence against their players in the first place.

The Wizard and the Princess is even today not totally without appeal. There is something attractive about its fairy-tale whimsy and its sprawling, discordant map. Discounting only ports of the original Adventure, The Wizard and the Princess was easily the largest adventure game yet to appear on a home computer. And then there are of course those pictures, the real heart of the game’s contemporary appeal. Quaintly appealing today, they were a technical tour de force in 1980, a reason to call family, friends, and neighbors over to the little Apple in the corner to just marvel. Owners of early home computers had had precious little immediately impressive to show off on their machines, just lots of blocky monochrome text showing the strangled English of Scott Adams or cryptic numbers and programming statements. Now they had something impressive indeed. Just as every generation considers its music to be rife with timeless classics and the music of the following generations to be worthless trash, every generation of gamers loves to accuse those who follow of being interested only in flashy graphics and sound. Well, guess what… every generation of gamers has always been interested in flashy graphics and sound. It’s just that this one had precious little of it available to them. If they had to find it in a game that has come to seem almost a caricature of obstinate old-school text adventures, so be it.

That said, there were gamers who reveled in the difficulty of games like The Wizard and the Princess. Some not only accepted balky two-word parsers but considered them part of the fun. In their view, solving a puzzle was a two-step process: figuring out the solution, and figuring out how to tell the computer about it. There was often an odd sort of machismo swirling around in these circles, as gamers who complained about obtuse gameplay were labelled as “not real adventurers.” To what extent this hardcore was rationalizing as a way of accepting the games they were stuck with anyway and to what extent they really, honestly liked guessing the verb and trying literally everything everywhere I’ll leave to you to decide. So much of gaming in this era was still in an aspirational phase, asking players to imagine that the primitive bundle of frustrations they were playing then was already the immersive interactive story everyone could see out there on the horizon, somewhere off in the future. Perhaps that begins to explain the curious sanguinity of everyone during the adventure game’s heyday, manifested in the refusal — still present in the nostalgic even today — to ever cry foul. But then the computer press was not terribly critical of any software, being bound up with the publishers as they were in a web of mutual self-interest. I know that as a kid who loved adventure games — or at least the idea of them — during the 1980s, I was frequently infuriated by the reality. I don’t think I was alone.

And the designers? Much of what led to designs like The Wizard and the Princess — the lack of understood “best practices” for game design, primitive technology, the simple inexperience of the designers themselves — I’ve already mentioned here and elsewhere. Certainly, as I’ve particularly harped, it was difficult with a Scott Adams- or Hi-Res-Adventures-level parser and world model to find a ground for challenging puzzles that were not unfair; the leap from trivial to impossible being made in one seemingly innocuous hop, as it were. However, some other pressures might not be immediately obvious. Consider that Ken and Roberta sold The Wizard and the Princess for $32.95. For that price, they needed to reward gamers with a good few hours of play. Yet there was a sharp limit to the amount of content they could deliver on a single floppy disk and a 48 K computer. (The Wizard and the Princess may have been an unusually big game by 1980 standards, but you can still easily get through it with a walkthrough in a half hour — and most of that time is spent waiting on pictures to load and draw themselves.) The obvious solution was to make the game hard, so gamers would be forced to spend literally hours scrabbling after each tiny chunk of actual content. Later, as piracy became more and more of a problem, some designers perhaps began to see almost unsolvable puzzles as a solution of sorts, for that way they could still get the pirates to buy hint books. Sierra itself stated repeatedly in the later 1980s that its hint-book sales often exceeded the sales of their associated games. What it neglected to mention, unsurprisingly, was the obvious incentive to produce unfair games this created, to earn some money even from the pirates and increase profits overall.

The real danger of bad design practice, whether born of laziness, greed, or simple rigidity (“that’s just the way adventure games are”), is that players get tired of being abused and move on. And if other genres begin to offer compelling, even story-rich experiences of their own, that danger becomes mortal. Through the 1980s designers had a captive audience of players entranced enough by the ideal of the adventure game and the technology used to bring it off that they were willing to accept a lot of abuse. When that began to change… But now we’re getting way, way ahead of ourselves.

For now, suffice to say that, whatever its failings, The Wizard and the Princess became an even bigger hit than Mystery House had been. Softalk magazine’s sales chart for that September already shows it the second biggest selling piece of software in the Apple II market, behind only the business juggernaut VisiCalc. It remained a fixture in the top ten for the next year, eventually selling over 60,000 copies and dwarfing the sales (10,000 copies) of Mystery House. By the end of the year, Ken and Roberta had a number of other products on the market under the On-Line Systems label, and had rented their first office space near their new home in Coarsegold. The long suffering John Williams gave up his promising career as the world’s first software distributor rep to become On-Line Systems Employee #1, where his annual salary amounted to about what he had been earning in a month with the distribution operation. In a very real way, The Wizard and the Princess made the company that would soon go on to worldwide success as Sierra Online.

If you’d like to try The Wizard and the Princess yourself, I have a disk image here that you can load into your emulator of choice. We’ll be leaving On-Line Systems for a while now, but we’ll drop in on them again down the line, at which time I promise to try not to treat their other works quite so harshly.

Next up: another group of old friends we met in an earlier post.

matt w

October 21, 2011 at 6:19 pm

Put the first note on top of the second. Presto, “HOCUS.”

matt w

October 21, 2011 at 6:25 pm

Illustrated graphically, in a way that will surely fail due to a lack of fixed-width font and/or preview:

_ _ _

| | | | | | | |

_ _

| | |_| |_ |_| _|

Mentally close that gap and you should get that word.

(I’ve never played this game, and I doubt I’d have been able to figure this out if I weren’t reverse-engineering the answer, but this is the kind of puzzle you see a lot in dem Flash escape-the-room games.)

matt w

October 21, 2011 at 6:26 pm

Ugh, total fail. I didn’t expect wordpress to erase EVERY SINGLE SPACE in between my underscores. Anyway, you see what I mean, I think.

Jimmy Maher

October 21, 2011 at 7:41 pm

Okay, yes, I… think so. :) You have just guaranteed that I’ll never try to play a Flash escape-the-room game…

matt w

October 21, 2011 at 9:49 pm

Do fixed-width tags work here?

matt w

October 21, 2011 at 11:31 pm

Garh. Sorry for wasting space with this. Anyway, using my Sweet Bro and Hella Jeff-level image editing skills, I have created a picture that should make it clear:

http://saucersofmud.files.wordpress.com/2011/10/wizard-princess-notes.png

It’s not so bad in escape-the-room games, really. Generally it’s clear that you have to enter (say) a four-digit code somewhere, so you’re looking around at everything for something that you can turn into a four-digit code. Which takes care of what seems like the really annoying part of this puzzle, which is figuring out what you’re supposed to do with “HOCUS” once you’ve pieced the notes together. (Is it possible that the parser strictly alternates between displaying the notes, which could actually be useful?) In this way, at least, the affordances tend to be clearer in escape-the-room games than they were here.

Of course you might not be awfully interested in games where you have combination locks with codes that are concealed around the room in bizarre ways, and I can’t say that many of these games have any sense of story. But some of them are beautiful in their way.

Jimmy Maher

October 22, 2011 at 4:18 am

Yes, that’s clear now. Thanks!

It’s the sort of thing that, with a bit of beta-testing feedback, could turn into a really cool puzzle. Here, though, the player doesn’t really have much chance of figuring it out, and that’s a shame, because the idea is quite ingenious. I’ve never heard much talk to beta-testing in all I’ve read about The Wizard and the Princess. I doubt there was much — these games were produced in a huge hurry, after all. Yet another reason for the unfairness of early adventure games…

Sniffnoy

October 23, 2011 at 8:29 am

To the extent that it works, it’s another good example of them taking advantage of the graphical capabilities, though!

Sniffnoy

October 24, 2011 at 1:18 am

That’s not due to WordPress – multiple spaces are always treated as one in HTML. If you want them to stay, you have to use the “pre” tag, which WordPress won’t allow here…

matt w

November 6, 2011 at 6:44 pm

Weeks later, I discovered this (warning: discusses 4channish homophobia).

I am filled with shame.

S. John Ross

October 21, 2011 at 6:22 pm

When this is all done, it’ll be a book, right? I want the book.

What’s most interesting to me about this entry is how much it’s caused me to examine the Player’s Bill of Rights. I’d given it a quick read once, long ago, and never really returned to it. It really is a strange tangle of common sense, insight, odd redundancy, occasional specificity and frequent subjectivity (lots of “not too much of this” or “a reasonable amount of that” going into the thinking).

It’s a good thing, that Bill, but it would be interesting seeing a spiffed-up version, streamlined a bit.

WCFields

October 22, 2011 at 7:17 am

I came here thinking the exact same thing: I really want all that as a book.

Jimmy Maher

October 22, 2011 at 1:38 pm

Yes, the Player’s Bill of Rights is kind of a rambling list that manages to be overly general and overly specific at the same time. Still, it’s one of those immenently Graham Neson-y things that I wouldn’t have any other way.

Which is not to say that it couldn’t be tightened up into a tighter ten-point list.

S. John Ross

October 21, 2011 at 6:38 pm

Note: your disk-image link leads to a file called Mystery_House.dsk, rather than (for example) Wiz_Princess.dsk or something of the sort.

Jimmy Maher

October 21, 2011 at 6:47 pm

Well, if you wanted a copy of Mystery House now you know where to find it. :)

But thanks. I fixed the link.

Felix Pleșoianu

October 21, 2011 at 7:19 pm

See, that’s why I made my own toy IF engine. I can now claim with confidence that even a two-word parser can be surprisingly tricky; it’s hard to imagine a more sophisticated one being written in assembler. On the other hand, adding synonyms is trivial, and effective hints don’t have to be wordy. In fact, the best kind of in-game hints aren’t textual.

The point about artificially extending the play time has more merit. But then, I can’t help but think how much of the memory taken by those big obnoxious mazes could have been better used. And if there had to be a maze (this being the early 1980es…) it could always be like the one in Ekphrasis: under a dozen locations, making perfect sense in context and beautiful to boot.

That they didn’t know better yet is excusable. That they took so long to evolve better game design, not so much.

Jimmy Maher

October 21, 2011 at 7:45 pm

Only one thing to quibble with here: mazes are actually very, very cheap in memory, computing power, and design time, especially if you reuse the room description and the picture (if any). That’s why designers loved them so much — they extended the length of the game hugely and made it seem really big, all on the cheap. Within a few years Level 9 would be advertising a game with over 1000 rooms, at least 950 of which were completely empty clones of one another.

gnome

October 22, 2011 at 7:24 am

You should really turn this series into a book.

john williams

October 29, 2011 at 12:50 am

Not disagreeing that some of the puzzles in Wizard and the Princess were a little obtuse. (I answered “hint” phone calls at On-line for years.)

I do, though, feel a need to defend the game a bit. We were all making it up as we went a long in 1981. There were very few adventure games out there – it was very new territory. It’s pretty easy to critique the game now through the view of 30 years of gaming, but back then people LOVED the game and couldn’t wait to buy what came next.

Jimmy Maher

October 29, 2011 at 8:02 am

Yes, of course. I’m all too aware that this was an anachronistic reading of the game. It’s a post I felt needed to be done, though, to illustrate some of the problems with these early games, and this game ended up being the (innocent?) victim. Certainly it’s not the only — or possibly even worst — offender.

And it’s quite cool to have a Sierra insider comment. Thanks for that!

J.P. McDevitt

December 24, 2012 at 7:49 am

As I and others have already posted, I’d be pretty stoked to see a full-length book from you focusing on Sierra (or perhaps adventure games and IF in general). I’ll be checking out “Software People” in the meantime.

Your bit about graphics is a hugely important point that is usually overlooked by adventure game fans. Adventure games from 1980-1996ish generally had the best available graphics on any platform, and that’s a huge reason for their success. When that focus was lost and adventure gamers started claiming graphics weren’t important, it was always about the stories and that 3D “sucks”, the genre died (recent mild resurgence not withstanding).

Gilles Duchesne

March 1, 2013 at 6:16 am

Just for the record, there is a French equivalent to “Polly wants a cracker” (“Coco veut un biscuit / gâteau”), and I suspect that feeding cracker-like nourishment to parrots is a fairly global phenomenon.

(The harder part would probably be to know how to call said cracker. Even in French, France & Québec don’t agree. :-) )

Dusty Sayers

April 3, 2013 at 1:36 pm

I have to say, for all its flaws (and we didn’t have much trouble figuring out HOCUS, although I didn’t finally beat the game until about 15 years after I first played it), I love Wizard and the Princess. That’s just because it was the first adventure game I really played, though, when my father (a computer science professor) bought an Apple ][e when I was a wee young lad. He would keep up with other players that he knew, even some that lived far away, and they would exchange what they knew about the game, and we kept paper maps of it by the computer all the time. Really, of course, it’s nostalgia that makes me love it.

I’ve really enjoyed this entire blog, because it’s sort of the world my father lived in when I was young (and before I was born) and that I grew up on the edges of. Thanks for bringing back all those great memories, and showing me many things I was unaware of about those times, too.

Bernie Paul

May 10, 2014 at 4:55 pm

Once again : “WOW” , Jimmy, even I haven’t had the pleasure of reading all the books referenced here on the subject of computing history, I feel that you already are “up there” with all those published authors. That’s the beauty of the blog phenomenon : it makes concepts like circulation, printing cost, mass-appeal, press coverage, bookstore shelf-space, truly obsolete and lets true talent like yours shine without any limitations.

I’d also like to contribute this to the post : Game design and playability are not limited by the technology, considering examples like Breakout (nobody who’s sane would tell it isn’t a great game), which Woz did initially on “almost-analog” hardware, or Apshai on the PET and TRS-80. I know i’m getting ahead of the story, but consider how Richard Garriot took RPG’s to the next level with Ultima I almost at the same time as Serenia came out, using the exact same hardware. And, considering that you don’t want to get into Robreta-bashing, let’s not compare Akalabeth’s technical achievemnets to Mystery House’s. Too bad Garriott wasn’t interested in “Adventure” games : he might have given both Infocom and Sierra a run for their money. And we know that even Ken Williams was aware of that, don’t we ?

Matthew

October 11, 2014 at 11:27 pm

Small nit: I mostly agree with you, but: “Since there is absolutely no way to identify this rock”. That’s not true: If you “look rock” at each rock, they all say they have a Scorpion under them, except the one.

DZ-Jay

February 9, 2017 at 10:09 am

Hi, there,

On the “HOCUS” puzzle, perhaps this is not obvious, but I thought it was rather simple: each note is one half of the word. If you put one on top of the other, they form the word. For example,

Top: |_|

Bottom: | |

Combined make an “H”:

|_|

| |

(I don’t know how this is rendering here, so my apologies if I’m confusing matters most.)

I haven’t played the game, so I do not know how clear this may seem from the TV screen, but it just seemed rather clear to me from the screenshots in this page. :)

Cheers!

-dZ.

Vince

July 4, 2023 at 5:14 am

The human brain is weird.

I spent an embarassing amount of time staring at the notes, trying to flip them, rotate them, superimposing them, and still could not figure it out.

But after reading the solution, I can totally see some people getting it right away.

The only other puzzle I had to look up is the one about the ring, that to me is a much more aggravating one.

All in all, I see where Jimmy’s criticism is coming from, but I agree with other commenters that laying it on this particular game is kind of unfair.

Had I played it as a kid on release I would have been completely blown away by it.

Much more than Mystery House, it DOES feel like an adventure, wia definite sense of progress and most of the other puzzles are fairly reasonable.

Mike Taylor

October 20, 2017 at 11:59 am

“Certainly, as I’ve particularly harped, it was difficult with a Scott Adams- or Hi-Res-Adventures-level parser and world model to find a ground for challenging puzzles that were not unfair.”

Interesting. I’ve seen you make this claim several times now in different posts, and each time I’ve read it I’ve found myself feeling uncomfortable. I don’t think it’s true at all. If we consider Spellbreaker, which we can probably agree is the pinnacle of hard-while-fair design, the great majority of the puzzles are solved using two-word VERB NOUN commands; and the very few that require an indirect object (THROW BOX AT OUTCROP) can be handled in the same way Scott Adams’s very first game handled THROW AXE AT DOOR — with an initial THROW BOX, followed by an “at what?” challenge and then AT OUTCROP.

In fact, I’m pretty sure that given enough patience I could reimplement Spellbreaker using ScottKit (i.e. as a TRS-80 format Scott Adams data file that can be run with, for example, ScottFree).

If I’m right, then the two-word parser and limited world-model of early adventure games are really not an adequate excuse for how flagrantly unfair a lot of the puzzles were. If I had to put it down to a single cause, I’d say lack of testing — caused by the very aggressive schedules of these companies racing each other to world domination.

Mike Taylor

October 20, 2017 at 12:25 pm

(Exception: I don’t think it would be possible to implement renaming the cubes.)

Jimmy Maher

October 20, 2017 at 2:01 pm

The cubes immediately sprang to mind as my counterexample when I read your comment. ;)

Based on your comment trail, you seem to be reading chronological order, so if you have the stamina you’ll eventually get to some discussions of this issue that you might find interesting in the context of the Magnetic Scrolls games. In a bid to one-up Infocom, they devoted a lot of time and energy to creating a parser capable of understanding ridiculously convoluted commands, like “USE THE TROWEL TO PLANT THE POT PLANT IN THE PLANT POT.” Their time might have been better devoted to other things, as absolutely no player is ever likely to type such a command in the real world. I’m sympathetic to the argument that the late-era Infocom parser reached a point that there wasn’t much to be done with it — at least within the constraints of 1980s technology — that would really lead to better games. The Scott Adams parser was obviously far from even the early Infocom parser, but I’m also willing to entertain the argument that Spellbreaker could be made to work with a two-word parser, at the expense of being able to write on the cubes and a certain amount of added frustration.

Where I think you’re rather underestimating the problem, though, is in the world model. There’s *a lot* going on in Spellbreaker behind the scenes on the simulation level to present a logically consistent environment for its intricate puzzles. This requires heaps of custom programming — real programming, not the simple verb-noun matching allowed by the Scott Adams database-driven approach. There comes a point, I would argue, where the Scott Adams engine just doesn’t allow you to make more *complicated* puzzles. So, if you’re invested in the idea of making a harder game, how do you do so? The temptation at this point to fall back on guess-the-verb and all the rest becomes immense.

It’s very easy to conflate the sophistication of the parser — the face of the game, from the player’s perspective — with the world modelling going on behind it, but the two are really almost completely separate problem domains. See the Phoenix mainframe games for an interesting example of games with rudimentary parsers but more sophisticated world models — if not quite as sophisticated as Infocom’s. I unfortunately don’t know of any games with good parsers and piss-poor world modelling; that would certainly be interesting to see. :)

Of course, you’re absolutely right that a lack of testing and hurried development cycles — not to mention the lack of any established standards for good and bad design — have much to do with the failings of most games of this era. A good designer who listens to feedback can create a perfectly enjoyable game within even the constraints of the 16 K Scott Adams engine. (In addition to the first four or five Scott Adams games, see Magnus Olsson’s The Dungeons of Dunjin, a very solid game running under a fairly primitive homegrown engine, for an example of a designer who understands the constraints of his tools and doesn’t try to push them farther than they will go.) Infocom’s innovations in the *craft* of adventure design, embodied by their thoroughgoing and absolutely dogged process of testing and polishing, had at least as much to do with their success as their technology.

Mike Taylor

October 20, 2017 at 10:36 pm

I think that writing on the cubes is the only part that I couldn’t implement in a Scott Adams game. Certainly the BLORPLE spell is trivial to implement, and the part where you go through a blocked exit and wind up in the box’s location would be pretty easy, too. In fact, now I have this crazy jones to actually go ahead and do it: implement Spellbreaker as a Scott Adams game. Somebody stop me :-)

(The grid-manoeuvering puzzle would probably also be impossible, but I’m not sure that would be a terrible loss.)

Yes, I am now going through your blog chronologically, having started out dipping into your various Infocom-game articles. I must be about the 10,000th person to tell you this, but it really is fascinating — and superbly written. I’ll look forward to the discussion you mention in the Magnetic Scrolls articles, which I certainly intend to reach. I’ve never played their games, but I remember PLANT THE POT PLANT IN THE PLANT POT from the articles that came out around that time, and thinking it was more impressive as a tech demo than it was useful as a gaming tool.

But similarly, even the early Infocom games had commands like PUT ALL THE BOOKS EXCEPT THE PURPLE ONE IN THE BAG THEN GO NORTH, which I have also never used. Ultimately, pretty much all parser-game commands come down to VERB NOUN INDIRECTOBJECT at most. And THROW AXE / At what? / AT DOOR does give you that, albeit clumsily. If I’m right, then to guess-the-verb and guess-the-noun we can add guess-the-indirect-object — and those three classes of problem encompass all parser-IF problems, when viewed purely mechanically. Of course, all that tells us is that purely mechanically is a stupid way to look at parser-IF problems. This is why how the problems appear within their world is so important — which in turn is why atmosphere counts for so much, hence Zork II being perhaps my favourite of all the Infocom games.

Still, you are right of course that the parser is only one half of the sophistication — the actual world model is more important and more interesting. The reason the grid-manoeuvering puzzle couldn’t be implemented in ScottKit is that the game can have no concept of what direction the other stone is in relative to your position (unless — *ugh* — you cheated by hard-coding all 15×14 = 210 possible combinations of your position and its. Let’s pretend I never raised that possibility.)

You ask “if you’re invested in the idea of making a harder game, how do you do so?”, and that is the key question — when using something like Inform, too. I think the answer does lie with deeper world modelling; but I’ve been surprised at how much of that you can do — or, at least, fake effectively — with relatively simple tools. There are some (I think) quite nice examples in a game I’m working on now, but I won’t spoil them until there’s enough there to be worth releasing.

Finally, I think that the 16k constraints on early micro adventures have been overstated. Adam’s format is grotesquely wasteful of space, and I am pretty sure I could easily get his files down to 2/3 their size without invoking any clever text compression. In other words, his games could easily have been 50% bigger. And “bigger” need not mean more rooms and items; it can mean more and cleverer actions.

Mike Taylor

March 11, 2020 at 11:43 pm

Hi, Jimmy. If you’re still interested in the question of how limiting the Scott Adams-style world model and parser are, I think you’d be intrigued by the recent Renga In Blue posts on Savage Island, part 2: see https://bluerenga.blog/2020/03/11/savage-island-part-2-robopirate/

Did you ever play that one?

Jimmy Maher

March 13, 2020 at 9:19 am

No, not in any serious way. Will take a look. Thanks!

Wouter Lammers

January 8, 2019 at 12:38 am

Slowly making my way through your excellent history lesson here, found a dead link to the Player’s Bill of Rights. Seems like this one does work: http://www.ifarchive.org/if-archive/programming/general-discussion/Craft.Of.Adventure.txt

Will Moczarski

August 24, 2019 at 9:02 pm

after the each tiny chunk of actual content

-> after each …

Jimmy Maher

September 1, 2019 at 9:58 am

Thanks!

Arthur DiBianca

February 2, 2020 at 4:48 pm

You’ll forgive this minor correction.

Early on you say it’s impossible to identify which rocks have a scorpion. But as I recall, you can type LOOK ROCK and you’ll see a picture of the rock with (usually) a scorpion behind it.

It’s an unexpected bit of player-friendliness!

Arthur DiBianca

February 4, 2020 at 6:28 pm

I know this is coming very late, but because of this game’s status as the first real adventure-with-pictures (and my own nostalgia), I was motivated to look into this desert maze a little more. I’ve always wanted to know exactly what was going on, and…now I do.

Spoilers follow?

The player can access 15 locations at the start: Serenia, the rattlesnake, and 13 identical desert rooms. Connections are all NWES, which makes it a little kinder than the “twisty little passages all alike”, but it’s the same kind of topological maze.

What’s amazing to me is how hard this maze is, even for seasoned adventurers.

Of the 13 desert rooms, 6 contain a rock. It’s in a different position in each room, but you have to pay VERY close attention. Really, you have to count pixels for some of them. A new player is likely to think the rocks are just randomized.

There are 7 empty desert rooms. Unfortunately, you only have 4 objects in your inventory, so even if you’re able to tell every rock apart, you wouldn’t have enough clues to map the whole thing. There will always be at least 3 identical empty rooms. Yikes.

One of the rocks is the “good” one, and I think it’s located in the most topologically distant room from the start. So if you start the game, and move around for a while (checking every rock with LOOK ROCK), you may feel like you’re never finding the good one.

But even worse, the good rock is located in almost exactly the same screen position as one of the earlier rocks. So unless you’re REALLY observant, you’ll think you’re back in an earlier room. Which makes mapping even harder.

To think this is the very first thing a player confronts — wow.

Arthur DiBianca

February 8, 2020 at 5:00 pm

Further investigation led me to this Apple 2 documentation:

https://tinyurl.com/ro6qatk

It looks like there was a folded card with a hint about getting past the rattlesnake. That makes the puzzle much more defensible. I don’t know if this hint was included with every version, though.

Jimmy Maher

February 8, 2020 at 5:03 pm

It was added later on because Sierra was being flooded with phone calls asking how to get past the starting area. ;)

Bert Whetstone

April 3, 2020 at 2:33 pm

I was drawn to adventure games back in my early teens, first playing the Scott Adams games and then on to Infocom when I got my own computer. I always considered Infocom to be the measure of sophistication for all text adventure games in those days, but I’ll never forget one major disappointment I experienced when playing Starcross.

Not long before I had read “Rendezvous With Rama”, so I was really getting into Starcross when I got stuck on a puzzle involving some rat-ant creatures causing a blockage. I must have spent hours retracing my steps, reviewing inventory items for ideas, going back through old saves to see if I missed anything, trying to come up with what must be some ingenious solution. But no – finally out of frustration I “hit rat-ant with metal cover” and that was it.

I’ll never forget how crestfallen I felt. This was an uncharacteristically barbaric solution from Infocom, especially given the futuristic and exploratory nature of Starcross. I’m sure there were similar faults in other Infocom titles over the years, but I always remember this solution as their major failing.

Now, after reading this blog entry of yours, I almost have to wonder if the solution to this Starcross puzzle wasn’t a subtle industry-insider jab at Roberta Williams?

Busca

March 3, 2022 at 8:24 am

Not being a native English speaker I’m not sure if this is an alternate spelling, but should “fair-tale” be “fairy-tale”?

Also, did John Williams really accept to become an employee where his annual salary amounted to about what he had been earning in a month with the distribution operation or was it the other way around? Given what his older brother probably was earning based on the flourishing sales, why would he do that? Then again, he apparently commented himself on this entry and did not challenge this… .

Jimmy Maher

March 4, 2022 at 8:38 am

Should be “fairy-tale,” yes. Thanks!

I’m pretty sure the anecdote about John Williams’s salary came from the horse’s mouth, although it’s been quite some years… ;)