After debuting within a few months of one another in 1981, the Ultima and Wizardry franchises proceeded to dominate the CRPG genre for the next several years to such an extent that there seemed to be very little oxygen for anyone else; their serious competition during this period was largely limited to one another. Otherwise there were only experiments that usually didn’t work all that well, like the Wizardry-meets-Zork hybrid Shadowkeep, along with workmanlike derivatives that all but advertised themselves as “games to play while you wait for the next Ultima or Wizardry.” One of these latter, SSI’s first CRPG Questron, so blatantly cloned the Ultima approach that it prompted outraged protest and an implied threat of legal action from Origin Systems. SSI President Joel Billings ended up giving Origin a percentage of the game’s royalties and some fine print on the back of the box: “Game structure and style used under license of Richard Garriott.” It’s highly debatable whether Origin really had a legal leg to stand on here, but these were days when Atari in particular was aggressively threatening publishers with similar “look and feel” lawsuits, sending lots of them running scared. Faced with the choice between a protracted legal battle and lots of industry bad will, neither of which his small company could well afford, or just throwing Origin some cash, Billings opted, probably wisely, for the latter.

In the competition between the two 800-pound gorillas of the industry, Wizardry won the first round with both the critics and the public. Compared to Ultima I, Wizardry I garnered more attention and more superlative reviews, and engendered a more dedicated cult of players — and outsold its rival by at least a two to one margin. Wizardry‘s victory wasn’t undeserved; with its attention to balance and polish, its sophisticated technical underpinnings, and its extensive testing, Wizardry felt like a game created by and for grown-ups, in contrast to the admittedly charming-in-its-own-way Ultima, which felt like the improvised ramblings of a teenager. (A very bright teenager and one hell of a rambler, mind you, but still…) The first Wizardry sold over 200,000 copies in its first three years, an achievement made even more remarkable when we consider that almost all of those were sold for a single platform, the Apple II, along with a smattering of IBM PC sales. While Infocom’s Zork may have managed similar numbers, it had the luxury of running on virtually every computer in the industry.

As early as 1982, however, the tables were beginning to turn. Richard Garriott continued to push Ultima forward, making games that were not just bigger but richer, prettier, and gradually more accessible, reaping critical praise and commercial rewards. As for Wizardry… well, therein lies a tale of misplaced priorities and missed opportunities and plain old mismanagement sufficient to make an MBA weep. While Ultima turned outward to welcome ever more new players to its ranks, Wizardry turned inward to the players who had bought its first iteration, sticking obstinately to its roots and offering bigger and ever more difficult games, but otherwise hardly changing at all through its first four sequels. You can probably guess which approach ended up being the more artistically and commercially satisfying. One could say that Ultima did not so much win this competition as Wizardry forfeited somewhere around the third round. Robert Woodhead, Andrew Greenberg, and Sir-Tech did just about everything right through the release of the first two games; after that they did everything just as thoroughly wrong.

As I wrote earlier, the second Wizardry, Knight of Diamonds, was an acceptable effort, if little more than a modest expansion pack to the original. It let players advance their characters to just about the point where they were too powerful to really be fun to play anymore, while giving them six more devious dungeon levels to explore, complete with new monsters and new tactical challenges. However, when the next game in the series, 1983’s Legacy of Llylgamyn, again felt like a not terribly inspired expansion pack, the franchise really began to go off the rails. Greenberg and Woodhead hadn’t even bothered to design this one themselves, outsourcing it instead to the Wizardry Adventurers Research Group, apparently code for “some of Greenberg’s college buddies.” Llylgamyn had the player starting over again with level 1 characters. Yet, incredibly, it still required that she purchase the first game to create characters; they could then be transferred into the third game as the “descendents” of her Wizardry I party. It’s hard to even account for this as anything other than a suicidal impulse, or (only slightly more charitably) a congenital inability to get beyond the Dungeons and Dragons model of buying a base set and then additional adventure modules to play with it. As Richard Garriott has occasionally pointed out over the years, in hewing to these policies Sir-Tech was effectively guaranteeing that each game in their series would sell fewer copies than the previous, would be played only by a subset of those who had played the one before. We see here all too clearly an unpleasant pedantry that was always Wizardry‘s worst personality trait: “You will start at the beginning and play properly!” It must have been about this time that the first masses of players began to just sigh and go elsewhere.

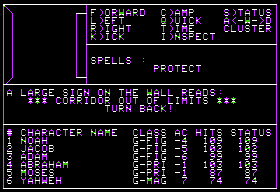

Speaking of pedantry: as I also described in an earlier article, a variety of player aids and character editors began to appear within months of the first Wizardry itself. Woodhead and Greenberg stridently denounced these products, pronouncing them “sleazy” in interviews and inserting a condescending letter to players in their game boxes stating their use would “interfere with the subtle balance” of the game and “substantially reduce their playing pleasure.” This is made particularly rich because, while Woodhead and Greenberg deserve credit for attempting to balance the game at all, the “subtle balance” of their first Wizardry was, in some pretty fundamental ways, broken; thus the tweaks they instituted for Knight of Diamonds. Did they really think players should ignore these issues and agree to spend dozens or hundreds of hours laboriously rebuilding countless lost parties, all because they told them to? Would players with so little capability for independent thought be able to complete the game in the first place? All the scolding did was put a sour face on the Wizardry franchise, giving it a No Fun Allowed personality in contrast to the more welcoming Ultima and, soon, plenty of other games. Players are perfectly capable of deciding what way of playing is most fun for them, as shown by the increasing numbers who began to decide that they could have more fun playing some other CRPG.

Meanwhile the Apple II’s importance as a gaming platform was steadily fading in the face of the cheaper and more audiovisually capable Commodore 64 in particular. Yet Sir-Tech made no effort for literally years to port Wizardry beyond the Apple II and the even less gaming-centric IBM PC. Their disinterest is particularly flabbergasting when we remember that the game ran under the UCSD Pascal P-Machine, whose whole purpose was to facilitate running the same code on multiple platforms. When asked about the subject, Woodhead stated that ports to the Commodore and Atari machines were “not technically possible” because neither ran any version of the UCSD Pascal language and because their disk systems were inadequate — too small in the case of the Atari and too slow in the case of the Commodore. Countless other companies would have and, indeed, did solve such problems by writing their own UCSD Pascal run-times — the system’s specifications were open and well-understood — and finding ways around the disk problems by using data compression and fast-load drivers. Sir-Tech was content to sit on their hands and wait for someone else to provide them with the tools they claimed they needed.

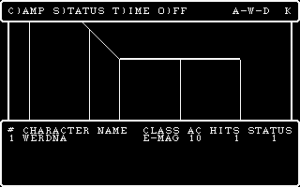

And then came the fiasco of Wizardry IV, a game which embodies all of the worst tendencies of the Wizardry series and old-school adventure gaming in general. This time Greenberg and Woodhead turned the design over to Roe R. Adams III, a fount of adventure-game enthusiasm who broke into the industry as a reviewer for Softalk magazine, made his reputation as the alleged first person in the world to solve Sierra’s heartless Time Zone, and thereafter seemed to be everywhere: amassing “27 national gaming titles,” writing columns and reviews for seemingly every magazine on the newsstand, testing for every publisher who would have him, writing manuals for Ultima games, and, yes, designing Wizardry IV. Subtitled The Return of Werdna, Wizardry IV casts you as the arch-villain of the first Wizardry. To complete the inversion, you start at the bottom of a dungeon and must make your way up and out to reclaim the Amulet that was stolen from you by those pesky adventurers of the first game.

Wizardry IV doesn’t require you to import characters from the earlier games, but that’s its only saving grace. Adams wanted to write a Wizardry for people just as hardcore as he was. Robert Sirotek, one of the few people at Sir-Tech who seemed aware of just how wrong-headed the whole project was, had this to say about it in a recent interview with Matt Barton:

It was insanely difficult to win that game. I had such issues with that. I felt that it went way beyond what was necessary in terms of complexity, but the people that developed it felt strongly to leave a mark in the industry that they had the hardest game to play — period, bar none. That’s fine if you’re not worried about catering to a customer and making sales.

Return of Werdna was the worst-selling product we ever launched. People would buy it, and it was unplayable. So they’d put it down, and word spread around. There were other hard-core players in the market that loved it. They said, “Ah, why doesn’t everybody do this?” Well, we don’t because you guys are a minority. If you’re a glutton for punishment, you’re going to have to get your pleasure somewhere else because nobody can survive catering to such a small number of people.

So, it was controversial in that way. In the end, I think I was proven correct that making crazy impossible products in terms of difficulty was not the way forward.

But insane difficulty is only part of the tale of Wizardry IV. It has another dubious honor, that of being one of the first notable specimens of a species that gamers would get all too familiar with in the years to come: that hot game of the perpetually “just around the corner!” variety. Sir-Tech originally planned to release Wizardry IV for the 1984 holiday season, just about a year after Legacy of Llylgamyn and thus right on schedule by the standard of the time. They felt so confident of this that, what with the lengthy lead times of print journalism, they told inCider magazine to just announce the title as already available in their November 1984 issue. It didn’t make it. In fact it took a staggering three more years, until late 1987, for Wizardry IV to finally appear, at which time inCider dutifully reported that Sir-Tech had spent all that time “polishing” the game. Those expecting a mirror shine must have been disappointed to see the same old engine with the same old wire-frame graphics. In addition to being unspeakably difficult, it was also ugly, an anachronism from a different era. Any remaining claim that the Wizardry franchise might have had to standing shoulder to shoulder with Ultima either commercially or artistically was killed dead by The Return of Werdna. Beginning with Wizardry V and especially VI, Sir-Tech would repair some of the damage with the help of a new designer, D.W. Bradley, but the franchise would never again be as preeminent in North America as it had in those salad days of 1981 and 1982.

Those remaining fans who were underwhelmed by Wizardry IV were left asking just what Sir-Tech had been up to for all those years during the middle of the decade. Robert Woodhead at least hadn’t been completely idle. With Wizardry III Sir-Tech debuted a new interface they called “Window Wizardry,” which joined the likes of Pinball Construction Set in being among the first games to bring some of the lessons of Xerox PARC home to Apple II users even before the Macintosh’s debut; both earlier Wizardry games were also retrofitted to use the new system. In 1984 Woodhead improved the engine yet again, to take advantage of the new Apple II mouse should the player be lucky enough to have one. And a few months after that his port to the Macintosh arrived.

But Woodhead’s biggest distraction — and soon his greatest passion, one that would change his life forever — was Japan. After first marketing Wizardry in Japan through Starcraft, a Japanese company that specialized in localizing American software for the Japanese market and vice versa, Sir-Tech signed a blockbuster of a deal with another pioneering company, ASCII Corporation, publishers of the magazine Monthly ASCII that can be justifiably called the Japanese Byte and Creative Computing all rolled into one. Increasingly as the 1980s wore on, ASCII also became a very important software publisher. With Woodhead’s close support, ASCII turned Wizardry into a veritable phenomenon in Japan, huge even in comparison to the height of its popularity Stateside. By the latter half of the decade there were entire conventions in Japan dedicated to the franchise; when Woodhead visited them he was mobbed like a rock star. In the face of such profits and fame, he began to spend more and more of his time in Japan. After leaving Sir-Tech in 1988 he lived there full-time for a number of years, married a Japanese woman, and eventually founded a company with his old buddy Roe Adams which is dedicated to translating Japanese anime and other cinema into English and importing it to the West; it’s still going strong today. The Japanese Wizardry line also eventually spun off completely from Sir-Tech to go its own way; games are still being made today, and now far outnumber the eight Sir-Tech Wizardry games.

That explains what Woodhead was doing, but it doesn’t do much to otherwise explain Sir-Tech’s Stateside sloth until we consider this: incomprehensibly, Sir-Tech clung to Woodhead as their only technical architect, placing their entire future in the hands of this one idiosyncratic, mercurial hacker. (Greenberg filled mostly a designer’s as opposed to programmer’s role, and never worked full-time on Wizardry; after the second game his role was largely limited to that of an occasional consultant.) So, Woodhead was fascinated by the potential of the GUI and thought the Macintosh pretty neat; thus those projects got done. But he was dismissive of the cheap machines from Commodore and Atari, so those markets, many times the size of the Mac’s when it came to entertainment software, were roundly ignored. Only in 1987, with Woodhead all but emigrated to Japan, did Sir-Tech finally begin to look beyond him, funding a Commodore 64 port at last. But by then it was far too late.

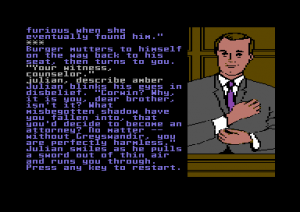

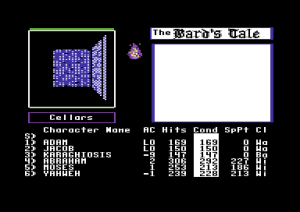

For the reason why, we have to rewind to 1984, and move our wandering eyes from Sir-Tech’s Ogdensburg, New York, offices to a struggling little development company in the heart of Silicon Valley who called themselves Interplay. Interplay already had a couple of modestly successful illustrated adventure games to their credit when a friend of founder Brian Fargo named Michael Cranford suggested that he’d like to make a sort of next-generation Wizardry game in cooperation with them. They were all big fans of Wizardry and Dungeons and Dragons — Cranford had been Dungeon Master for Fargo’s D&D group back in high school — so everyone jumped aboard with enthusiasm. There’s been some controversy over the years as to exactly who did what on the game that would eventually become known as The Bard’s Tale, but it seems pretty clear that Cranford, who had already authored a proto-CRPG called Maze Master that was restricted in scope by its need to fit onto a 16 K cartridge, was the main driver. The most important other contributor was Bill “Burger” Heineman, who helped Cranford with some of the programming and did much of the work involved in porting the game to systems beyond its initial home on the Apple II. (Bill Heineman now lives as Rebecca Heineman. As per my usual editorial policy on these matters, I refer to her as “he” and by her original name only to avoid historical anachronisms and to stay true to the context of the times.) After Cranford parted ways with Interplay following The Bard’s Tale II, Heineman would take over his role of main programmer and designer for The Bard’s Tale III.

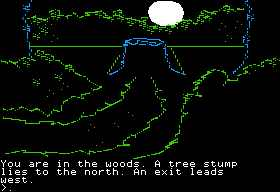

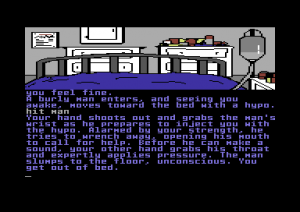

The Bard’s Tale on the Commodore 64. Note that this predates the screenshot immediately above by two full years.

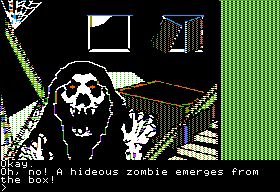

In retrospect, the most surprising thing about the first Bard’s Tale, which was published through Electronic Arts in late 1985, is that nobody did it sooner. It was certainly no paragon of original design. If anything, it was even more derivative of Wizardry than Questron had been of Ultima, evincing not just the Wizardry template of play but almost the exact same screen layout and even most of the same command keys, right down to a bunch of spells that were cast by entering their four-letter codes found only in the manual (a useful form of copy protection). But Wizardry, thanks to Sir-Tech’s neglect, was vulnerable in ways that Ultima was not. Interplay did the commonsense upgrades to the Wizardry formula that Sir-Tech should have been doing, filling the game with colorful graphics, occasional dashes of spot animation, a bigger variety of monsters to fight, more equipment and spells and classes to experiment with. And, most importantly of all to its commercial success, they made sure a Commodore 64 version came out simultaneously with the Apple II. In the years that followed they funded loving ports to an almost Infocom-like variety of platforms, giving it further graphical facelifts for next-generation machines that the early Wizardry games would never reach, like the Commodore Amiga, Atari ST, and Apple IIGS.

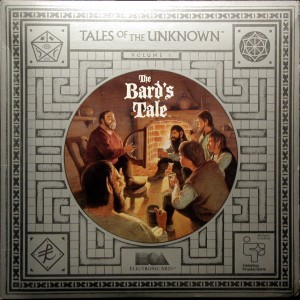

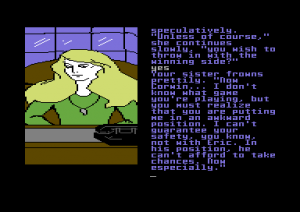

The Bard’s Tale‘s original touches, while by no means entirely absent, tinker with the Wizardry formula more than revamp it. Instead of doing everything outside of the dungeons via a simple textual menu system, you now have an entire town with a serious monster infestation of its own to explore. In the town of Skara Brae you can find not only equipment shops and temples and all the other stops typical of the errand-running adventurer but also the entrances to the dungeons themselves — five of them, with a total of 16 levels between them, as opposed to the original Wizardry‘s single dungeon of 10 slightly smaller and generally simpler levels. But the most obvious way that The Bard’s Tale asserts its individuality is in the whimsical character class of the bard himself, who can perform magic by playing songs; you actually hear his songs playing on your computer, another flourish The Bard’s Tale has over its inspiration. More importantly, he lends the game some of his lovably roguish personality: “When the going gets tough, the bard goes drinking,” ran the headline of EA’s advertisements. The official name of the game is actually Tales of the Unknown, Volume 1: The Bard’s Tale; the rather white-bread Tales of the Unknown, in other words, was originally intended as the franchise’s name, The Bard’s Tale as the mere subtitle of this installment. Interplay originally planned to call the next game The Archmage’s Tale, next stop in a presumed cycling through many fantasy character archetypes. The bard proved so popular, however, such an indelible part of the game’s personality and public image, that those plans were quickly set aside. The next game was released as The Bard’s Tale II: The Destiny Knight, the Tales of the Unknown moniker quietly retired.

Commodore 64 owners especially, starved as they had been of the Wizardry experience for years, set upon The Bard’s Tale like a horde of the mad dogs who are some of the first monsters you encounter in its labyrinths. Combined with EA’s usual slick marketing, their pent-up desire was more than enough to make it a massive, massive success, the first CRPG not named Wizardry to be able to challenge the Ultima franchise head to head in terms of sales, if not quite critical respect (it was hard for even the forgiving gaming press of the 1980s to completely overlook just how derivative a game it was). The Bard’s Tale would wind up selling 407,000 copies by the end of 1990, becoming the best-selling single CRPG of the 1980s and single-handedly making Interplay a force to be reckoned with in the games industry. They would remain one of the major creative forces in gaming for the next decade and a half; we’ll have occasion to visit their story again and in more detail in future articles.

There is, however, a certain whiff of poetic justice to the way that Interplay allowed this particular franchise to go stale in much the same way that Sir-Tech had Wizardry. The Bard’s Tale II (1986) and III (1988) were each successful enough on their own terms, but a story all too familiar to Sir-Tech played out as each installment sold worse than the one before. The series then faded away quietly after The Bard’s Tale Construction Set (1991), for which Interplay polished up some of their internal authoring tools for public consumption. By then The Bard’s Tale was already long past its heyday, its position of yin to Ultima‘s yang taken up by yet another franchise, the officially licensed Advanced Dungeons and Dragons games from SSI. (At least two attempts at a Bard’s Tale IV never came to fruition, doomed by the IP Hell that resulted from Interplay parting company with EA; EA owned the name of the franchise, Interplay most of the content. Interplay’s attempt at a Bard’s Tale IV did eventually come to market as Dragon Wars, actually a far more ambitious game than any of its predecessors but one that was markedly unsuccessful commercially.)

The sequels did add some wrinkles to the formula. The Bard’s Tale II deployed a strangely grid-oriented wilderness to explore in addition to towns — six of them this time — and dungeons, and added range as a consideration to the combat engine. The Bard’s Tale III: The Thief of Fate offered more welcome improvements to the core engine, including a simple auto-mapping feature and, at long last, the ability to save the game even inside a dungeon. But mostly the sequels fell into a trap all too typical of CRPGs, of offering not so much new things to do as just ever larger amounts of the same interchangeably generic content to slog through and laboriously map; over the course of the trilogy we go from 16 to 25 to an absurd 84 dungeon levels. This despite the fact that there just aren’t that many permutations allowed by this simple dungeon-delving engine and its spinners, magical darknesses, teleporters, and traps. Long before the end of the first Bard’s Tale it’s starting to get a bit tedious; by the time you get to the sequels it’s just exhausting. It’s not hard to understand Interplay’s motivation for making the games ever huger. Gamers have always loved the idea of big games that give them more for their money, and by the third game Interplay’s in-house tools were sophisticated enough to allow them to slap together a gnarly dungeon level in probably much less time than it would take the average player to struggle through it. Still, the early Wizardry games stand up better as holistic designs today. The first Wizardry‘s ten modest dungeon levels were enough to consume quite some hours, but not too many; the game is over right about the time it threatens to get boring, a mark the latter Bard’s Tales in particular quite resoundingly overshoot.

So, I’m quite ambivalent about The Bard’s Tale franchise as a whole, as I admittedly am about many old-school CRPGs. To my mind, there are some time-consuming games, like Civilization or Master of Orion, that appeal to our better, more creative natures by offering endless possibilities to explore, endless interesting choices to make. They genuinely fascinate, tempting us to immerse ourselves in their mysteries for all the right reasons. And then there are some, like The Bard’s Tale or for that matter FarmVille, that somehow manage to worm their ways into our psyches and activate some perversely compulsive sense of puritanical duty. Does anyone really enjoy mapping her twentieth — not to mention eightieth! — dungeon inside a Bard’s Tale, wrestling all the while with spinners and teleporters and darkness squares that have long since gone from being intellectually challenging to just incredibly, endlessly annoying? The evidence of The Bard’s Tale‘s lingering fandom would seem to suggest that people do, but it’s a bit hard for me to understand why. Oh, I suppose one can enjoy the result, of having ultra-powerful characters or seeing chaos held at bay for another day via another page of graph paper neatly filled in, but is the process really that entertaining? And if not, why do so many of us feel so compelled to continue with it? Is there ultimately much point to a game that rewards not so much good play as just a willingness to put in lots and lots of time? I want to say yes, if the game has something to say to me or even just an interesting narrative to convey, but The Bard’s Tale, alas, has nothing of the sort. Ah, well… maybe it’s just down to my distaste for level grinding as an end in itself as opposed to as a byproduct of the interesting adventures you’re otherwise having — a distaste everyone obviously doesn’t share.

It can be oddly difficult to find a “clean” copy of this hugely popular game in its most popular incarnation, the Commodore 64 version. Most versions floating around on the Internet are played on, hacked, and/or, all too often, corrupted. If you want to experience The Bard’s Tale, a commercial and historical landmark of its genre despite any misgivings I may have about it, you may therefore want to download a virgin copy from this site. Alternately, all three games are included as a free bonus with a 2004 game of the same name that otherwise has very little to do with its predecessors. That’s available for various platforms from GOG.com, Steam, Google Play, and iTunes. Next time we’ll turn to a CRPG that does have something important to say, arguably the first of all too few examples of same in the history of the genre.

(Matt Barton has posted interviews with some of the folks I write about in this article on his YouTube channel: Rebecca Heineman, Brian Fargo, and Robert Sirotek. Interviews with Michael Cranford can be found on Lemon 64 and the RPG Codex. The Bard’s Tale Compendium has some background on the games and the people who made them. Now Gamer’s history of SSI includes details of the Questron tension with Origin Systems. The inCider magazine articles referenced above are in the November 1984 and November 1987 issues. See the August 1988 Computer Play for more on the Wizardry phenomenon in Japan, and the October 1983 Family Computing for Greenberg at his hectoring worst on the subject of third-party player aids and the necessity of playing Wizardry the “right” way. Finally, I located the Bard’s Tale sales figures in the March 1991 issue of Questbusters.)