At the end of 1984 Alan Miller and Bob Whitehead, two of the members of Atari’s Fantastic Four who had founded Activision along with Jim Levy, split away from the latter company to form yet another, Accolade. I must admit that their publicly stated reasons for doing so strike me as a bit difficult to understand. In a fairly recent article in Retro Gamer magazine, the two say that Activision was “too entrenched in its console roots” for their tastes, an odd claim to make considering that Activision 2.0 had just had a huge hit on computers with Ghostbusters and that virtually all new development was focused in that direction. In another interview, Miller states he was “puzzled why Activision couldn’t make a profit,” which may point to concerns with Levy’s management. Or the whole thing may have come down to personal conflicts that everyone is too diplomatic to discuss. Regardless, Miller and Whitehead made the bold decision to start their own company at a seemingly terrible time, just as established publisher after established publisher was dying. With no one in the financial sector willing to touch home-computer software with the proverbial ten-foot pole, they financed the venture entirely by themselves, drawing on their savings from the glory days of Activision 1.0, when the games they had created for the Atari VCS had sold in the hundreds of thousands or millions, with royalty checks to match. With Larry Kaplan having been lured back to Atari in 1982, their departure left only David Crane and Jim Levy at Activision from among the founders. In two or three more years they too would be gone.

Tellingly, Miller and Whitehead’s first creative hire was not a programmer or designer but rather Mimi Doggett, a talented graphic artist who had spent more than four years with Atari. She would help Accolade walk a fine line between innovation and commercial appeal with markedly more success than Activision 2.0 would manage over the next several years. Accolade excelled at finding subject matter that was unexplored or done only badly by other games, but which nevertheless had plenty of potential mass appeal; they had none of Activision 2.0’s more avant-garde tendencies. They implemented gameplay around their fictional conceits that was always fast-paced, accessible, and not too time-consuming if you didn’t want it to be, but that also always allowed for at least a modicum of depth — Trip Hawkins’s old formulation of “simple, hot, and deep” writ larger than Electronic Arts themselves often managed. Miller:

Games should be worn by the user without feeling like they’re wearing them. They should be intuitively obvious to use, and as transparent as possible to the user. The user should feel that they’re in an experience.

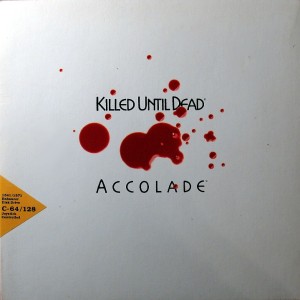

The cherry on top was graphics that were often technically spectacular, especially on Accolade’s bread-and-butter platform the Commodore 64 (this despite Accolade being located almost next door to Apple’s headquarters in Cupertino), but which also sported an unusually refined aesthetic sensibility thanks to Doggett. The same sensibility extended to the packaging, which would be shortlisted for a Clio Award in 1987. Accolade’s early output evinces none of the fit-and-finish problems that so often plagued Activision 2.0, being uniformly polished to a mirror shine. They were rewarded with a stellar reputation among Commodore owners in particular; a new Accolade game was guaranteed to sell — and, of course, to be widely pirated — based simply on the name on the box.

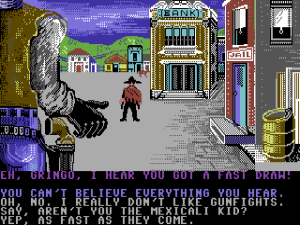

Accolade’s two 1985 launch titles, one designed and programmed by each of the founders with the invaluable assistance of Doggett, were already fine examples of the approach that would come to define the company. Miller’s Law of the West was a cowboy western, a genre that, while amply explored in arcade games like Gun Fight and Boot Hill, was much less common in computer games. As a new sheriff in town, you wander the streets talking with the citizens and solving problems, sometimes just with conversation, sometimes with your trusty six-shooter. The additional layer of strategy and narrative texture afforded by the conversations would prove to be typical of Accolade games to come, which were almost never just simple action games. Whitehead’s Hardball, meanwhile, was a wonderfully attractive and playable action-oriented baseball game, a sport which had previously been explored only badly or through dry statistics-based simulations like SSI’s Computer Baseball.

As soon as Accolade established themselves with Law of the West and Hardball, both of which became big hits and made the company profitable in rather astonishingly short order, they began seeking outside developers with a similar sensibility whose work they could publish to supplement their in-house games. One of the first and most long-lived of these relationships would be the one with the tiny Ottawa-based house Artech.

Founded in 1981 by Rick Banks and Paul Butler, Artech already had a considerable resume to their credit before partnering with Accolade. The company had been born as a developer of games for the NABU Network, an early effort to deliver computer content through Ottawa’s cable-television lines that’s been billed — sometimes slightly overbilled in my opinion, but that’s as may be — as “the Internet, ten years ahead of its time.” Artech’s secret weapon, acquired soon after the deal with NABU, was Michael Bate, a colorful self-proclaimed “ideas man” with a degree in music who had already worked as a journalist, a radio producer, a pedal-steel player in a country band, and a railroad brakeman. He personally designed most of the NABU games, which were then programmed largely by Banks and Butler.

One of Artech’s most popular games for NABU featured B.C., the lead character of the long-running newspaper comic strip of the same name. Artech’s work for NABU got them noticed by Sydney Development Corporation, a Vancouver-based company with fingers in lots of computer-industry pies, from project management to retail stores, that now dreamed of becoming Canada’s first major home-computer software developer. Sydney scooped Artech up to become their “Video Games/Educational Software Division” in the spring of 1983. The first game the team made for Sydney once again featured B.C. Published by Sierra for most viable home computers of the era as well as the ColecoVision console, B.C.’s Quest for Tires became a big hit not only in Canada but also in the United States and Europe. (Our old friend Chuck Benton of Softporn fame would do some of the ports.)

Within a year or two Bate would declare he wasn’t “overly proud” of B.C.’s Quest for Tires, produced as it was quickly under the stipulations of a licensing agreement. Luckily, the parent company in Vancouver largely stepped back after that and gave the little group in Ottawa remarkable freedom to make whatever games they wanted to make. Sydney’s management had enough problems of their own, finding themselves caught in an economic downward spiral as the home-computer industry crashed and reams of overambitious plans fell through. This left the games division as the only division of the company actually making money. By 1987 the group that had once been Artech would become Artech once more, managing to extricate themselves from the grip of their dying parent and become an independent company once again; this second Artech incarnation would last until 2011.

Meanwhile, and under whatever name, there were games to be made. The once and future Artech really came into their own with a pair of World War II air-combat games, Dam Busters (1985) and Ace of Aces (1986), that were amongst the first outside productions to be published by Accolade. They fit perfectly with the general Accolade aesthetic, being very accessible and audiovisually impressive games that recreated unusual crannies of every gamer’s favorite war that set them a little apart. Dam Busters put the player in charge not of the typical B-17 but rather of an RAF Lancaster night bomber trying to destroy a German dam using one of Barnes Wallis’s “bouncing bombs.” Ace of Aces, meanwhile, put her behind the controls not of the usual P-51 or P-38 but of a Mosquito fighter-bomber. Uninterested in the technical minutiae of flight and military hardware that enthralled companies like subLOGIC and MicroProse, Bate nevertheless did extensive research to create “aesthetic simulations of historical events,” what he called “docu-games” that tried to capture the spirit of their subjects, like a good movie; Dam Busters was in fact directly inspired by the 1955 classic of the same name. Artech and Accolade were amply rewarded for their efforts: Ace of Aces alone sold over 500,000 copies between North America and Europe during its commercial lifetime. Given numbers like that, later efforts from Artech like Apollo 18 and The Train, both released in 1987, understandably continued in largely the same vein. The latter, a crazy chase across Nazi-occupied France, is in the reckoning of many Artech’s 8-bit masterpiece. It really does play like a great old-school war flick — appropriately so, since it was loosely based on a 1964 Burt Lancaster vehicle.

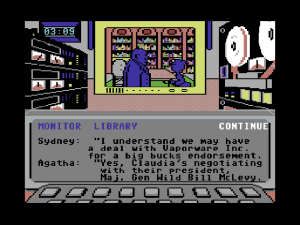

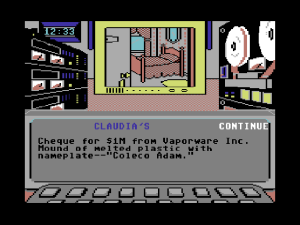

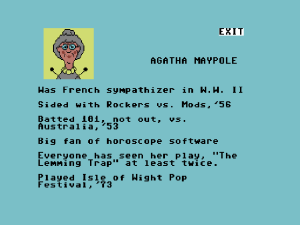

If The Train is Artech’s predictable masterpiece, the ultimate expression of their established approach, 1986’s Killed Until Dead, whose design is credited jointly to Michael Bate and Rick Banks, is their wonderfully unique outlier. It’s very unusual indeed as both an Accolade and an Artech production in that it has no action elements at all. While, as Paul Butler once joked, Artech’s usual target demographic was “teenage boys, ages 12 to 45,” Killed Until Dead feels pointed in a different direction. The 21 snack-sized mysteries it offers all take place at a meeting of the Murder Club, a stand-in for the Detection Club that created The Scoop. Its five members are each (fictional) established mystery writers, modeled on various famous figures in the fictional and nonfictional history of murder: Mike Stammer (Mickey Spillane’s detective Mike Hammer), Agatha Maypole (a hybrid of Agatha Christie and her sleuth Miss Marple), Lord Peter Flimsey (Dorothy L Sayers’s detective Lord Peter Wimsey), Sydney Meanstreet (a hybrid of Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe and actor Sydney Greenstreet, who played him on the radio), and Claudia von Bulow (a feminine version of accused murderer Claus von Bülow). Your own detective is Hercule Holmes, a name whose antecedents I trust need no explanation.

To add an interesting twist to the usual proceedings, you aren’t trying to solve a murder here but rather to prevent one Murder Club member from killing another; who the potential killer and victim will be will of course vary from episode to episode. The deeply creepy means you use to accomplish this is a spying setup to die for. You’ve not only bugged the writers’ rooms as well as other areas of the mansion at which they’re staying for both video and audio, but you’ve also got a master key that lets you get into their rooms when they’re out. The twelve hours of game time you have to solve each mystery takes about thirty minutes of real time; once you start a mystery, the clock is always ticking. As you quickly discover after settling in with your first mystery or two, each episode follows a fairly predictable pattern. First you break into all of the suspects’ rooms to see what they’re up to. This should reveal some information about various planned liaisons, which you’ll want to view live and/or record; in the later, more difficult mysteries in particular, there will often be two meetings taking place at the same time, making your ability to record one while you view another essential. Next you’ll want to call some or all of the suspects on the telephone to see what you can shake loose; they’ll also call you from time to time to further their own agendas, whether by offering useful tips or trying to put you off the scent (such misleading information can be as useful as any other if you can read between the lines). Finally, with all of the information you’ve compiled from all of the above, plus each suspect’s background dossier, you should be able to deduce murderer, victim, weapon, and motive and stop the crime by calling the murderer up and accusing her before the clock strikes midnight and she does the deed — and does you in for good measure (you can’t really blame her for that considering the spying you’ve been up to).

The NSA can only dream of a setup like this one. And if you don’t get the reference to “Wild Bill,” well, keep reading this blog. We’ll get there soon enough.

Killed Until Dead is steeped in the heritage of mystery, murder, and cozy mayhem, the whole game an extended, meta-textual love letter to its genre that crime-fiction aficionados will sink into like a warm blanket. Its most controversial design choice then and now is the mechanism for forcing your way into each suspect’s room: you have to answer a multiple-choice trivia question about the gloriously macabre history of murder on page, screen, and sometimes even real life. Certainly such a requiring of outside knowledge is a questionable choice by most modern standards of design. For all that, though, I wouldn’t want to lose the questions; they just give this loving homage of a game that much more opportunity to spread the love. Nowadays if you don’t know the name of Sam Spade’s partner (Miles Archer) or what Hitchcock used to fake the blood in Psycho‘s shower scene (it was chocolate syrup; luckily he was shooting in black and white), well, that sort of thing is only a Google search away. (Admittedly, the rabbit holes your searches lead you down may end up consuming more time than the cases themselves.) Or just make your best guess, and come back again in thirty minutes (game time) if you’re wrong; there’s enough time to spare that you’ll probably be okay.

Indeed, none of the cases, not even those of “Super Sleuth” level, are really all that difficult. When Dorte and I played we failed to solve one or two early on when we were just getting the hang of things, but once we understood the pattern of play we solved every case with relative ease. And on the whole I think that’s fine; I believe it’s far, far better for a game like this one to be too easy than too hard. There are obvious similarities here to other short-form mystery games that use the same setting, cast of characters, and props over and over again in the service of different cases, like Murder on the Zinderneuf or for that matter Cluedo. But what separates Killed Until Dead from the likes of “Colonel Mustard in the library with the candlestick” is Artech’s decision not to try to randomly generate the individual permutations. Each case is carefully, lovingly, handcrafted, with gobs of wit and charm; Dorte liked Miss Maypole so much that she’d just start giggling every time the fussy old bat would enter the picture. The best decision Artech made for Killed Until Dead was the one to spend lots of time designing the 21 bespoke cases rather than wrestling with a random case generator that would almost inevitably disappoint. The disadvantage of their approach is of course that it makes Killed Until Dead a very finite experience; once you’ve played the 21 cases there’s nothing else to be done. This was a bigger concern in 1986, when games were expensive, and, especially for many younger players without the financial wherewithal to buy them very often, needed to last a long, long time. Nowadays it’s really no concern at all. By my lights, this game has just about the perfect amount of content, ending just when all of the potential has been pretty much wrung out of its repeating stage, actors, and props.

Killed Until Dead is a little delight of a game that I highly recommend. It offers attractive graphics and that level of refined, casual playability that had already by 1986 become such a trademark of Accolade. And it offers that little something extra, love for its chosen genre. In fact, I realize now that I’ve used some variation of the word “love” several times in describing Killed Until Dead. Love for a topic combined with a sense of fair play and a willingness to polish, polish, polish will take a game designer a long way. Feel free to download it and load it up in your favorite Commodore 64 emulator. (A tip for users of VICE: turn off “True Drive Emulation” to make the normally unbearable Commodore loading times barely noticeable.) It makes for a great way to spend a few cozy winter evenings.

(Print sources for this article include the November 1986 and October 1987, Computer Gaming World, the November 1985 Family Computing, the August 1985 Zzap!, the November 1985 Sinclair User, Retro Gamer 50, the Arcade Express dated May 8 1983, and the Ottawa Citizen from May 31 1982, August 28 1982, September 20 1983, and September 29 1983, and February 15 2007. More information on NABU can be found at IEEE Canada and York University.)

Soren Johnson

December 4, 2014 at 5:38 pm

Glad to hear you liked Killed Until Dead! I played it so long ago, but I remember it being one of the few games that did murder mysteries well.

Caleb Wilson

December 4, 2014 at 8:37 pm

I guess “Claudia von Bulow” could be a reference to Claus von Bülow — not a detective, but involved in a notorious (attempted) murder case. He’s a real person, and was portrayed by Jeremy Irons in “Reversal of Fortune”.

Lisa H.

December 5, 2014 at 12:13 am

That’s what I assume to be the case.

Asterisk

December 5, 2014 at 12:18 am

A minor note about screenshots: in the era of graphical games you’re now entering, most of the games you discuss will have resolutions of 320×200. This was the standard resolution of NTSC C64, Amiga, Atari ST, Apple IIgs, and CGA/EGA/VGA DOS systems. This will continue to be so through the mid-’90s, as games generally increased color depth rather than resolution as graphics hardware improved.

You may note that 320×200 has an aspect ratio of 16:10. However, the monitors that these games were displayed on were universally 4:3. Since a CRT monitor has no fixed pixel grid like an LCD, a 320×200 image displayed on a 4:3 screen would simply be stretched vertically, which would cause the individual pixels in the images to be not square, but to themselves have an aspect ratio of 5:6. The large majority of computer games from about 1985 to 1995 were written with this pixel aspect ratio in mind (though a small number were intended to be played with square pixels at a screen aspect ratio of 16:10).

So if you want to display pixel-perfect reproductions of most classic 320×200 games on a modern screen, the only way you can do it is to upscale the image to 1600×1200 without any interpolation. This will transform each pixel in the original image into a region of 5×6 pixels in the resulting image. If you want a smaller image, you can then downsample to a lower 4:3 resolution. e.g. 640×480 with interpolation; the result will still be a more authentic reproduction of the original graphics.

You can use ImageMagick on the command line or in a script to do all of this automatically:

convert source.png -filter point -resize 1600x1200! target.pngThe resulting PNGs won’t be much bigger than the originals if you use an optimization tool like optipng, as the rescaled images are highly compressible.

This applies to all of the games in this post, even Killed Until Dead — the 384×247 resolution is an effect of capturing a C64 screenshot with the overscan borders included: if you crop those out, you’ll see that the actual game resolution is still 320×200.

Apologies if this comes off as too pedantic or nitpicky. This is easily the best blog around on computer-gaming history, and I figured that given the quality of the research and commentary you provide, more authentic reproductions of the graphics would be very fitting.

Jimmy Maher

December 5, 2014 at 7:45 am

Not at all. That’s wonderfully helpful. I was always vaguely aware that the aspect ratio wasn’t right — and have lots of memories for that matter of fighting with non-square pixels on the C64 and Amiga back in the day. Square pixels were one of the few things that made me immediately happy when switching from the Amiga to Wintel.

I’ve followed your suggestions to modify the images in this article, and will continue to do so from now on. As for the backlog of images in older posts… that’s a task for another day.

Thanks!

MagerValp

December 8, 2014 at 2:42 pm

Since we’re already nitpicking it’s actually not quite as simple as resizing to 4:3, since that doesn’t account for the display border. There’s also a large difference between PAL, which has almost square pixels, and NTSC, where the pixel aspect ratio is roughly 3:4. A lot of gory details can be found here: http://hitmen.c02.at/temp/palstuff/.

Another factor is the effect that PAL and NTSC encoding has on color reproduction. One of my favorite images for demonstrating the effect is Weeee! by Mermaid, though few commercial games exploited it. It does gives the image a lot of softness, especially with an RF or composite cable.

The easiest way to get decent C64 screenshots is to enable CRT emulation in VICE, make sure aspect ratio correction is on, and use the system shortcut to make snapshots (Command-Shift-4 on OS X, Alt+PrtScn on Windows).

Ed Finkler

December 18, 2016 at 7:32 pm

Oh dear, now I want to write a batch processor for upscaling old screenshots correctly.

Lisa H.

December 5, 2014 at 12:21 am

My Canadian husband adored BC’s Quest for Tires and played it with his brother approximately 93 hours a day, to hear him tell it.

In my turn, I adored Killed Until Dead. I remember the very last mystery stumping me, but then I was only 10 or 12 years old at the time. I may very well have worn out the disk on this one. I remember my mother taking me to Accolade’s offices (since we lived close by) in person to get a replacement of some disk of one of their games. I can’t remember for certain if it was this, but it’s a fair candidate.

You don’t think Sydney Meanstreet is meant to refer to Sydney Greenstreet?

matt w

December 5, 2014 at 2:45 am

Surely it is; but Greenstreet played Nero Wolfe on the radio (so saith Wikipedia), so it can be an indirect reference to Wolfe as well.

Jimmy Maher

December 5, 2014 at 8:14 am

With the help of you folks, I think I’ve managed to get the antecedents all correct now, although if anyone spots any more references we’ve missed feel free to chime in. Thanks!

Scott

December 5, 2014 at 12:38 am

Law of the West! I would play that game over and over as a kid, memorising routes and choices, trying to get the best ending. The animation when the sheriff pulls out his gun was pretty awesome for the time.

I didn’t play much other Accolade titles aside from the Test Drive series – Killer is Dead sounds right up my alley though, so thanks for providing it!

Matthew

December 5, 2014 at 3:14 am

No idea if you are going to get there in a future post (this is a couple of years ahead, 1987 I believe), but:

For me, Accolade is always about Test Drive. You’d start it up, and the opening screen started with a computerized voice saying “Accolade Presents” (even under the PC speaker if I’m remembering correctly). In hindsight it was a great piece of marketing.

Test drive was a fun game also, probably one of the most fun car game’s I’ve ever played (though to this day Pit Stop II, while much more primitive and a few years in the past by this point, has a special place in my heart for it’s multi-player capabilities).

Jimmy Maher

December 5, 2014 at 7:56 am

I played Test Drive a lot as well, albeit on the Amiga rather than the 64. It was made by the *other* Canadian developer that found a steady publisher in Accolade, Distinctive Software. They also made the very unique Accolade’s Comics.

I doubt Test Drive will get a feature piece, since I don’t know how much there is to really *say* about it when you get down to it beyond “fun game (for a limited time).” But I’m sure it will nevertheless come up again, maybe as part of an article that focuses more on Comics, about which there’s quite a lot to say. And I do sense some of the Test Drive DNA in later racing games like Need for Speed… hmm, maybe there is something to say about it after all. :)

Jim Leonard

December 8, 2014 at 7:22 pm

There is a lot of history in the Test Drive series that could warrant its own article. For example, DSI re-used bits of the technology for the DOS port of SEGA’s Outrun, and were sued for it. The game itself has only vagely-disguised credits (“USI”) that betray the true developers.

Dehumanizer

December 5, 2014 at 8:09 am

Great article, as always. :)

I read somewhere that Accolade’s name was chosen to ensure it appeared before Activision on lists in alphabetical order — just like Activision intentionally did the same to Atari. I wonder if, had anyone from Accolade started a new company, they would name themselves “Aardvark”. :)

I played all these games (except Law of the West and Hardball) on the Spectrum, at the time. Man, Killed Until Dead was a big cassette…

Typo: “Nero Wolf” should be Nero Wolfe.

Jimmy Maher

December 5, 2014 at 8:17 am

Thanks!

Accolade’s name was indeed chosen for that reason. Another that they rejected was “Acclaim,” which of course comes even earlier. Sure enough, an Acclaim Entertainment popped up soon after.

David Boddie

December 6, 2014 at 4:13 pm

Aardvark was indeed used for a software publisher whose most recognisable title also involved a caveman on a quest.

John Elliott

December 5, 2014 at 12:25 pm

I was so fond of Killed Until Dead on the Spectrum that I hacked it to run from the floppy drive rather than cassette tape. And also did some work on the data format the mysteries are held in, though I never got round to writing an editor program to create new mysteries.

dk

December 5, 2014 at 1:23 pm

I do remember a lot of these games from Accolade (loved Law of the West and was awestruck by Hardball’s graphics, although being German baseball was too strange of a game for me to play it), but I had never ever heard of Killed Until Dead before. I can only assume that the trivia questions (heavily U.S. aligned, I assume) prevented it from becoming popular in Germany. Sounds like a fun game, though, so I’m looking forward to trying it out.

Jimmy Maher

December 5, 2014 at 1:50 pm

Actually I think Germans would probably have done okay with the questions themselves, as I believe mysteries of the Agatha Christie type are quite popular there — judging at least from my in-laws’ taste in books and television! But the game is heavily dependent on text. While language localization had started to happen a little bit by the mid-1980s, most publishers were still just promoting untranslated games with limited text in non-English-speaking countries and hoping for the best. This is actually also an unremarked hidden cause for the commercial travails text adventures began to encounter in comparison to their peers by the mid-1980s…

Felix

December 6, 2014 at 9:37 am

On the plus side, most computer games being in English was one of the things that forced me to start learning the language back in the day. I wouldn’t be where I am but for that. It’s sad that people clamor for more and more software localization instead of learning the language everyone else is already speaking. And I don’t mean Chinese or Russians who also need to cross the writing barrier, but people from European countries, who shouldn’t even have much of a problem learning a much simpler language than their own.

Jimmy Maher

December 7, 2014 at 4:17 pm

Well, English is not hugely complicated grammatically, but it’s a horribly inconsistent language, a veritable minefield of special cases and exceptions. I know lots of very smart non-native speakers who have been working with English for years who still struggle with when to use “something” and when “anything,” when to put an “-ing” ending on a verb and when not to, and when to change out “don’t” for “doesn’t.” So, I’m not sure I’d characterize it as “simple” to learn.

English skills are extremely important, as just about every country in the world recognizes by now. However, there’s a huge gulf between functional literacy in the sense of being able to interact on a basic level socially or at a conference or even to read a business brief and the sort of total fluency that allows one to effortlessly appreciate a novel, film, or computer game with its much more affective and nuanced language. People play computer games to relax and entertain themselves. It makes perfect sense to me that they’d want to do that in the language that feels easiest and most natural to them. I watch a film in Danish if I want to improve my language skills; I watch a film in English when I just want to relax. So, I should judge not others lest I be judged myself, as a wise man somewhere once said.

Sebastian Redl

January 3, 2019 at 2:08 pm

“a veritable minefield of special cases and exceptions.”

And that’s not even touching pronunciation. That’s just one big disaster.

Wade

December 5, 2014 at 10:30 pm

I never heard of Killed Until Dead until today, either. I’m Australian.

Law of the West is great. I somehow forgot it was Accolade. My friend would have me in stitches with his inappropriate gun-pulling-out. ‘Little Jimmie’ would be walking across the screen, and my friend would whip out the six shooter and yell, ‘DIE JIMMIE, DIE!’ But Little Jimmie could shoot back, and sometimes we lost.

I still have Accolade’s Comics in the EA-type packaging, but in my head I never thought, ‘Oh, this is the same Accolade that does Test Drive.’ Accolade’s branding with Test Drive was so strong, my brain just goes to Test Drive and Test Drive 2 immediately when I think of Accolade, but that’s probably also because I didn’t own a C64, though I did playi on them at friends’ houses all the time.

B.C.’s Quest… urgh, I think I got a complex from that game. It was so frustrating, but I didn’t stop until I beat it. It’s the earliest I remember punching the computer desk in anger, and I still have some kind of physical temper to this day.

The way I acquired B.C.’s Quest is odd. This was the early 80s, and there was a games sale on at Grace Bros, a big Australian chain store, now called Myers. So my dad bought me some games. One of them was the Sierraventure ‘Crossfire’ (cost about $15, I think), which I was really keen for.

When I opened Crossfire, the disk inside the box was B.C.’s Quest. I tried it and found it weird. We took it back to the shop, and the guy opened up a bunch more Crossfires, and each one had the B.C.’s Quest disk inside instead of Crossfire.

Finally he said ‘I can’t get you a Crossfire, but you can keep this other game, which would normally cost you $60.’ And so we did. And I do slightly rue that day.

I did eventually get Crossfire at a warehouse games sale, and in spite of its simplicity, it brought a lot of joy.

LoneCleric

December 5, 2014 at 10:33 pm

As a young small-town teenager visiting Quebec City with my folks, I went to a computer store hoping to get my hands on an adventure game. I remember looking for Perry Mason, without success, and left the store with Killed Until Dead.

Even though it wasn’t exactly what I had been looking for, I absolutely loved it. I went through all the cases, and the text still proved a challenge to my grasping English. (For many years, I pronounced the title “Kyle’d until dead”. :-) )

In 2002, while looking for soft. dev. employment in Ottawa, I found out that Artech was based in town, and sent them my resume. Never heard back from them, alas.

PS: The paper is named Ottawa Citizen, like the city itself. ;-)

Jimmy Maher

December 5, 2014 at 10:45 pm

Thanks!

You did pretty well. Killed Until Dead is a *much* more playable game than Perry Mason…

Dehumanizer

December 5, 2014 at 11:32 pm

So, like I said, I played the Spectrum version of Killed Until Dead (on tape) back in the eighties, but now, inspired by this post, I went back to the game (on C64, since it looks and sounds much better), and played through the first couple of cases, and I was reminded of something that had bugged me back in the day…

(spoiler warning: if you’ve never played the game and intend to, you may want to stop reading)

I don’t know if this is changed in later cases, but at least in the first few ones, every suspect (including the future victim) always knows everything about the murder, so, after you break into everyone’s room, you can get all the crime details (except for the motive) with just a few calls. After that, monitoring and/or recording conversations is useful only for finding out the motive (which you can usually guess from the first couple of conversations) — and because they tend to be funny, of course. Still, you can solve most of the mystery just by placing less than half a dozen phone calls to *any* of the characters (with the caveats that the murderer and the victim can’t acknowledge their own roles, but can still confirm everything else).

Or does this change later in the game?

Jimmy Maher

December 5, 2014 at 11:41 pm

I don’t recall noticing this. I’d say it doesn’t extend past the first group of cases. There are actually a few tricky cases in the later going where certain suspects will not only not have all the answers but will try to actively mislead you. And you sometimes have to not only ask the right person the right questions but also strike the right tone. So there’s a bit of psychology involved.

As I wrote in the article, this isn’t a hugely difficult game by any means, but I wouldn’t call it rote or trivial either. It strikes a really nice balance in that respect.

John Elliott

December 6, 2014 at 9:35 pm

In the easy mysteries, every suspect knows everything. In later ones, not everybody knows, and some suspects know things that aren’t correct. For example, in “Of Pooches and Pillows”, Claudia has a motive to kill Mike, and Agatha has a motive to kill Sydney. Claudia, Peter and Mike know one set of murderer, victim and location; Agatha and Sydney know the other. But only one of the murders is the right one.

Dehumanizer

December 7, 2014 at 10:27 pm

Thanks for the replies, both of you. I admit I never played past the first difficulty level (either in 1987 or this week) (though yesterday I played the first case of the second level, and didn’t see any real difference… yet). Now I’m more optimistic…

I confess that, due to the multi-load nature of the game, where I assumed each load was just “data” (to be interpreted by a non-changing engine), I really though the game wouldn’t add any new features (such as non-omniscient suspects) later. I’ll have to keep playing, now. :)

Andrew

December 7, 2014 at 2:42 pm

I loved “Killed Until Dead” on the Spectrum, which it was ported to in 1987. I bought it one Saturday morning in the summer holidays and played it so hard that I’d solved all the cases by Sunday evening!

As you rightly say, they’re not really that difficult, but the pleasure lies more in the way the deduction and solution logically hang together, rather than a feeling of solving a particularly tough one. I was heavily into classic detective fiction at the time (still got quite a soft spot for it now as well), so ralso eally enjoyed the trivia questions scattered throughout the game.

One minor point for others who played it on the Spectrum – does anyone else remember one of the early cases in fact being fiendishly difficult? I think the murderer changed halfway through on that one and I kept trying to nominate the wrong person, to the point where I ended up randomly accusing people by process of elimination until I got the right one, and even then it wasn’t until I read the solution that I saw where I’d been going wrong!

Jimmy Maher

December 7, 2014 at 4:02 pm

There was one in the middle that was unusually difficult for that reason, although I couldn’t tell you exactly which one. Dorte and I thought at the time, okay, now this is about to start getting really tricky. But then none of the other cases, even at the “Super Sleuth” level, were ever quite that gnarly again.

I believe the Spectrum version was cut down from 21 cases to something like 14 due to tape storage limitations. So you might want to try the C64 version sometime to see what you missed!

John Elliott

December 7, 2014 at 9:34 pm

The Spectrum version has all 21 cases; it came on two cassettes, one with the main program and one with the mysteries.

When playing it on emulators, I found that the .SLT version (patched to have the emulator load the data directly) worked better for me than the .TZX version (loading from the emulated cassette).

Andrew

December 7, 2014 at 6:32 pm

Actually, the Spectrum version did have about 20 cases, albeit you had to load them seperately from the main game, which is how they got round the memory problem. Pretty sure the game was across two tapes to facilitate this.

Agree with you on the absolute so and so of a case as I both (a) can’t remember which one it was either and (b)do remember it incongrously appeared on one of the easier skill levels!

The other memory I have of that game is that I solved it so quickly that it was the only time I was ever able to send some playing tips into “Crash”. I dutifully noted down all the solutions and sent them in, only to find in next month’s issue that, quick as I’d been, I still hadn’t quite been the first person to finish it…

Tried to play it on a Spectrum emulator a while ago but couldn’t get it to load, so will definitely give your C64 version a go. Best part is that 27 years is plenty long enough to have forgotten all the solutions…

Dehumanizer

December 7, 2014 at 10:35 pm

Except for nostalgia purposes, I suggest you go for the C64 version. Not only does it look and sound a lot better (the faces are funnier, the silhouettes when monitoring rooms are much easier to recognize, etc.), but in the Speccy version the suspects’ individual tunes, play a lot slower and can’t be skipped, so calling multiple suspects soon becomes a chore. It’s more noticeable if you’ve just been playing the C64 version; I never complained about it back in 1987 or so.

Don’t get me wrong, the Spectrum port is perfectly fine, but the game is just more pleasant to play on the C64.

John Elliott

December 8, 2014 at 12:08 pm

I found pressing fire while a suspect’s tune was playing would skip it.

Regarding not getting it to load, I’ll have to revise my earlier comment about the TZX versus SLT versions; the SLT version loads for me where the TZX doesn’t, but it’s buggy (some rooms don’t render and the solution screens don’t show).

Dehumanizer

December 8, 2014 at 5:20 pm

Hmm, I’m sure I tried pressing fire. Maybe it needs to be done between sounds, as the 48K’s beeper stops the CPU, so maybe it’s not responsive all the time…

Brandon Campbell

December 17, 2014 at 12:37 pm

Hardball was one of my favorite Commodore 64 games ever, and the only one that my dad would play with me! I also remember wanting Test Drive as a kid, but never getting a chance to play it except in emulation many years later.

Harlan Gerdes

January 9, 2017 at 6:07 am

I had most of these games for my c64, Test Drive was a great game and I have fond memories of playing it. But the clincher for me liking these games were the attention that was given to the detail graphically and the user interface. As a kid (with little money), I took notice of which companies had the best games and I would always look for Accolade games because I knew I couldn’t go wrong with devoting time to playing them. Great article! I thoroughly enjoyed reading it.

DZ-Jay

March 7, 2017 at 1:42 am

Typo alert…

>> “… ending just when the all of the potential…”

An extra “the” before “all”?

Jimmy Maher

March 7, 2017 at 8:08 am

Thanks!

DZ-Jay

March 7, 2017 at 1:49 am

I don’t think I’ve ever played “Killed Until Dead,” although the character profile screenshot in the article seems vaguely familiar. Perhaps it was in my games collection and I just never got around to it. You made it sound so good that I now can’t wait to give it a shot. :)

Thanks!

-dZ.

DZ-Jay

March 7, 2017 at 10:43 am

I know that this is probably not the forum for this, but I just downloaded VICE (it’s been several years since I last tried it) and the game from the links you provided above and tried to run it. I tried playing the game, but all I get is a title screen with a thunder boom that repeats over and over. At some point, somehow, I managed to get an introduction screen stating the premise of the game, but couldn’t move from there.

Pressing any key results in nothing (well, the function keys causes the title screen to restart). What am I missing?

Man, I feel like when I was 12 years-old, when I was trying to figure out how to get one of the games in my extensive pirated collection to run and do something. LOL!

-dZ.

Jimmy Maher

March 7, 2017 at 1:18 pm

The game expects to be played entirely via joystick. If you don’t have one — most people don’t these days — you can use the keyboard instead. The number pad works quite well for this. Look under the Settings -> Joystick Settings menu in VICE to configure the “virtual” joystick. Note that, like most single-player Commodore 64 games, this one uses the joystick in port 2.

You probably accidentally managed to hit the key standing in for the fire button when you progressed past the title screen…

DZ-Jay

March 8, 2017 at 10:10 am

Hi, Jimmy,

Thank you for taking the time to respond. I can’t believe I made the exact same mistake I tended to do as a kid: hooking up the joystick to port #1 and then wondering why it never worked. LOL!

I am able to use the game now. Thanks!

-dZ.

Ben

May 2, 2022 at 8:06 pm

time consuming -> time-consuming

liasons -> liaisons

Jimmy Maher

May 3, 2022 at 1:42 pm

Thanks!