During 1983, the year that Brian Moriarty first conceived the idea of a text adventure about the history of atomic weapons, the prospect of nuclear annihilation felt more real, more terrifyingly imaginable to average Americans, than it had in a long, long time. The previous November had brought the death of longtime Soviet General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev and the ascension to power of Yuri Andropov. Brezhnev had been a corrupt, self-aggrandizing old rascal, but also a known, relatively safe quantity, content to pin medals on his own chest and tool around in his collection of foreign cars while the Soviet Union settled into a comfortable sort of stagnate stability around him. Andropov, however, was to the extent he was known at all considered a bellicose Party hardliner. He had enthusiastically played key roles in the brutal suppression of both the 1956 Hungarian Revolution and the 1968 Prague Spring.

Ronald Reagan, another veteran Cold Warrior, welcomed Andropov into office with two of the most famous speeches of his Presidency. On March 8, 1983, in a speech before the American Society of Evangelicals, he declared the Soviet Union “an evil empire.” Echoing Hannah Arendt’s depiction of Adolf Eichmann, he described Andropov and his colleagues as “quiet men with white collars and cut fingernails and smooth-shaven cheeks who do not need to raise their voice,” committing outrage after outrage “in clean, carpeted, warmed, and well-lighted offices.” Having thus drawn an implicit parallel between the current Soviet leadership and the Nazis against which most of them had struggled in the bloodiest war in history, Reagan dropped some big news on the world two weeks later. At the end of a major televised address on the need for engaging in the largest peacetime military buildup in American history, he announced a new program that would soon come to be known as the Strategic Defense Initiative, or Star Wars: a network of satellites equipped with weaponry to “intercept and destroy strategic ballistic missiles before they reach our own territory or that of our allies.” While researching and building SDI, which would “take years, probably decades, of effort on many fronts” with “failures and setbacks just as there will be successes and breakthroughs” — the diction was oddly reminiscent of Kennedy’s Moon challenge — the United States would in the meantime be deploying a new fleet of Pershing II missiles to West Germany, capable of reaching Moscow in less than ten minutes whilst literally flying under the radar of all of the Soviet Union’s existing early-warning systems. To the Soviet leadership, it looked like the Cuban Missile Crisis in reverse, with Reagan in the role of Khrushchev.

Indeed, almost from the moment that Reagan had taken office, the United States had begun playing chicken with the Soviet Union, deliberately twisting the tail of the Russian bear via feints and probes in the border regions. “A squadron would fly straight at Soviet airspace and their radars would light up and units would go on alert. Then at the last minute the squadron would peel off and go home,” remembers former Undersecretary of State William Schneider. Even as Reagan was making his Star Wars speech, one of the largest of these deliberate provocations was in progress. Three aircraft-carrier battle groups along with a squadron of B-52 bombers all massed less than 500 miles from Siberia’s Kamchatka Peninsula, home of many vital Soviet military installations. If the objective was to make the Soviet leadership jittery — leaving aside for the moment the issue of whether making a country with millions of kilotons of thermonuclear weapons at its disposal jittery is really a good thing — it certainly succeeded. “Every Soviet official one met was running around like a chicken without a head — sometimes talking in conciliatory terms and sometimes talking in the most ghastly and dire terms of real hot war — of fighting war, of nuclear war,” recalls James Buchan, at the time a correspondent for the Financial Times, of his contemporaneous visit to Moscow. Many there interpreted the speeches and the other provocations as setting the stage for premeditated nuclear war.

And so over the course of the year the two superpowers blundered closer and closer to the brink of the unthinkable on the basis of an almost incomprehensible mutual misunderstanding of one another’s national characters and intentions. Reagan and his cronies still insisted on taking the Marxist rhetoric to which the Soviet Union paid lip service at face value when in reality any serious hopes for fomenting a worldwide revolution of the proletariat had ended with Khrushchev, if not with Stalin. As the French demographer Emmanuel Todd wrote in 1976, the Soviet Union’s version of Marxism had long since been transformed “into a collection of high-sounding but irrelevant rhetoric.” Even the Soviet Union’s 1979 invasion of Afghanistan, interpreted by not just the Reagan but also the Carter administration as a prelude to further territorial expansion into the Middle East, was actually a reactionary move founded, like so much the Soviet Union did during this late era of its history, on insecurity rather than expansionist bravado: the new Afghan prime minister, Hafizullah Amin, was making noises about abandoning his alliance with the Soviet Union in favor of one with the United States, raising the possibility of an American client state bordering on the Soviet Union’s soft underbelly. To imagine that this increasingly rickety artificial construct of a nation, which couldn’t even feed itself despite being in possession of vast tracts of some of the most arable land on the planet, was capable of taking over the world was bizarre indeed. Meanwhile, to imagine that the people around him would actually allow Reagan to launch an unprovoked first nuclear strike even if he was as unhinged as some in the Soviet leadership believed him to be is to fundamentally misunderstand America and Americans.

On September 1, 1983, this mutual paranoia took its toll in human lives. Korean Air Lines Flight 007, on its way from New York City to Seoul, drifted hundreds of miles off-course due to the pilot’s apparent failure to change an autopilot setting. It flew over the very same Kamchatka Peninsula the United States had been so aggressively probing. Deciding enough was enough, the Soviet air-defense commander in charge scrambled fighters and made the tragic decision to shoot the plane down without ever confirming that it really was the American spy plane he suspected it to be. All 269 people aboard were killed. Soviet leadership then made the colossally awful decision to deny that they had shot down the plane; then to admit that, well, okay, maybe they had shot it down, but it had all been an American trick to make their country look bad. If Flight 007 had been an American plot, the Soviets could hardly have played better into the Americans’ hands. Reagan promptly pronounced the downing “an act of barbarism” and “a crime against nature,” and the rest of the world nodded along, thinking maybe there was some truth to this Evil Empire business after all. Throughout the fall dueling search parties haunted the ocean around the Kamchatka Peninsula, sometimes aggressively shadowing one another in ways that could easily lead to real shooting warfare. The Soviets found the black box first, then quickly squirreled it away and denied its existence; it clearly confirmed that Flight 007 was exactly the innocent if confused civilian airliner the rest of the world was saying it had been.

The superpowers came as close to the brink of war as they ever would — arguably closer than during the much more famed Cold War flash point of the Cuban Missile Crisis — that November. Despite a “frenzied” atmosphere of paranoia in Moscow, which some diplomats described as “pre-war,” the Reagan administration made the decision to go ahead with another provocation in the form of Able Archer 83, an elaborately realistic drill simulating the command-and-control process leading up to a real nuclear strike. The Soviets had long suspected that the West might attempt to launch a real attack under the cover of a drill. Now, watching Able Archer unfold, with many in the Soviet military claiming that it likely represented the all-out nuclear strike the world had been dreading for so long, the leaderless Politburo squabbled over what to do while a dying Andropov lay in hospital. Nuclear missiles were placed on hair-trigger alert in their silos; aircraft loaded with nuclear weapons stood fueled and ready on their tarmacs. One itchy trigger finger or overzealous politician over the course of the ten-day drill could have resulted in apocalypse. Somehow, it didn’t happen.

On November 20, nine days after the conclusion of Able Archer, the ABC television network aired a first-run movie called The Day After. Directed by Nicholas Meyer, fresh off the triumph of Star Trek II, it told the story of a nuclear attack on the American heartland of Kansas. If anything, it soft-pedaled the likely results of such an attack; as a disclaimer in the end credits noted, a real attack would likely be so devastating that there wouldn’t be enough people left alive and upright to make a story. Still, it was brutally uncompromising for a program that aired on national television during the family-friendly hours of prime time. Viewed by more than 100 million shocked and horrified people, The Day After became one of the landmark events in American television history and a landmark of social history in its own right. Many of the viewers, myself among them, were children. I can remember having nightmares about nuclear hellfire and radiation sickness for weeks afterward. The Day After seemed a fitting capstone to such a year of brinksmanship and belligerence. The horrors of nuclear war were no longer mere abstractions. They felt palpably real.

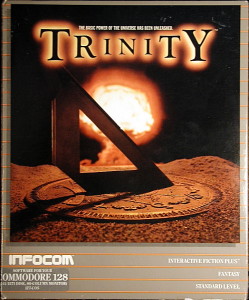

This, then, was the atmosphere in which Brian Moriarty first conceived of Trinity, a text adventure about the history of atomic weaponry and a poetic meditation on its consequences. Moriarty was working during 1983 for A.N.A.L.O.G. magazine, editing articles and writing reviews and programs for publication as type-in listings. Among these were two text adventures, Adventure in the Fifth Dimension and Crash Dive!, that did what they could within the limitations of their type-in format. Trinity, however, needed more, and so it went unrealized during Moriarty’s time at A.N.A.L.O.G. But it was still on his mind during the spring of 1984, when Konstantin Chernenko was settling in as Andropov’s replacement — one dying, idea-bereft old man replacing another, a metaphor for the state of the Soviet Union if ever there was one — and Moriarty was settling in as the newest addition to Infocom’s Micro Group. And it was still there six months later, when the United States and the Soviet Union were agreeing to resume arms-control talks the following year — Reagan had become more open to the possibility following his own viewing of The Day After, thus making Meyer’s film one of the few with a real claim to having directly influenced the course of history — and Moriarty was agreeing to do an entry-level Zorkian fantasy as his first work as an Imp.

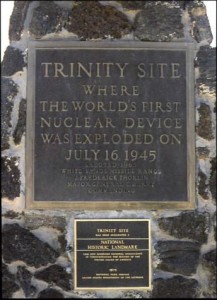

Immediately upon completion of his charming Wishbringer in May of 1985, Moriarty was back to his old obsession, which looked at last to have a chance of coming to fruition. The basic structure of the game had long been decided: a time-jumping journey through a series of important events in atomic history that would begin with you escaping a near-future nuclear strike on London and end with you at the first test of an atomic bomb in the New Mexico desert on July 16, 1945 — the Trinity test. In a single feverish week he dashed off the opening vignette in London’s Kensington Gardens, a lovely if foreboding sequence filled with mythic signifiers of the harrowing journey that awaits you. He showed it first to Stu Galley, one of the least heralded of the Imps but one possessed of a quiet passion for interactive fiction’s potential and a wisdom about its production that made him a favorite source of advice among his peers. “If you can sustain this, you’ll have something,” said Galley in his usual understated way.

Thus encouraged, Moriarty could lobby in earnest for his ambitious, deeply serious atomic-age tragedy. Here he caught a lucky break: Wishbringer became one of Infocom’s last substantial hits. While no one would ever claim that the Imps were judged solely on the commercial performance of their games, it certainly couldn’t hurt to have written a hit when your next proposal came up for review. The huge success of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, for instance, probably had a little something to do with Infocom’s decision to green-light Steve Meretzky’s puzzleless experiment A Mind Forever Voyaging. Similarly, this chance to develop the commercially questionable Trinity can be seen, at least partially, as a reward to Moriarty for providing Infocom with one of the few bright spots of a pretty gloomy 1985. They even allowed him to make it the second game (after A Mind Forever Voyaging) written for the new Interactive Fiction Plus virtual machine that allowed twice the content of the normal system at the expense of abandoning at least half the platforms for which Infocom’s games were usually sold. Moriarty would need every bit of the extra space to fulfill his ambitions.

He plunged enthusiastically into his research, amassing a bibliography some 40 items long that he would eventually publish, in a first and only for Infocom, in the game’s manual. He also reached out personally to a number of scientists and historians for guidance, most notably Ferenc Szasz of the University of Albuquerque, who had just written a book about the Trinity test. That July he took a trip to New Mexico to visit Szasz as well as Los Alamos National Laboratory and other sites associated with early atomic-weapons research, including the Trinity site itself on the fortieth anniversary of that fateful day. His experience of the Land of Enchantment affected him deeply, and in turn affected the game he was writing. In an article for Infocom’s newsletter, he described the weird Strangelovean enthusiasm he found for these dreadful gadgets at Los Alamos with an irony that echoes that of “The Illustrated Story of the Atom Bomb,” the gung-ho comic that would accompany the game itself.

“The Lab” is Los Alamos National Laboratory, announced by a sign that stretches like a CinemaScope logo along the fortified entrance. One of the nation’s leading centers of nuclear-weapons research. The birthplace of the atomic bomb.

The Bradbury Museum occupies a tiny corner in the acres of buildings, parking lots, and barbed-wire fences that comprise the Laboratory. Its collection includes scale models of the very latest in nuclear warheads and guided missiles. You can watch on a computer as animated neutrons blast heavy isotopes to smithereens. The walls are adorned with spectacular color photographs of fireballs and mushroom clouds, each respectfully mounted and individually titled, like great works of art.

I watched a teacher explain a neutron-bomb exhibit to a group of schoolchildren. The exhibit consists of a diagram with two circles. One circle represents the blast radius of a conventional nuclear weapon; a shaded ring in the middle shows the zone of lethal radiation. The other circle shows the relative effects of a neutron bomb. The teacher did her best to point out that the neutron bomb’s “blast” radius is smaller, but its “lethal” radius is proportionally much larger. The benefit of this innovation was not explained, but the kids listened politely.

Trinity had an unusually if not inordinately long development cycle for an Infocom game, stretching from Moriarty’s first foray into Kensington Gardens in May of 1985 to his placing of the finishing touches on the game almost exactly one year later; the released story file bears a compilation datestamp of May 8, 1986. During that time, thanks to the arrival of Mikhail Gorbachev and Perestroika and a less belligerent version of Ronald Reagan, the superpowers crept back a bit from the abyss into which they had stared in 1983. Trinity, however, never wavered from its grim determination that it’s only a matter of time until these Pandorean toys of ours lead to the apocalyptic inevitable. Perhaps we’re fooling ourselves; perhaps it’s still just a matter of time before the wrong weapon in the wrong hands leads, accidentally or on purpose, to nuclear winter. If so, may our current blissful reprieve at least stretch as long as possible.

I’m not much interested in art as competition, but it does feel impossible to discuss Trinity without comparing it to Infocom’s other most obviously uncompromising attempt to create literary Art, A Mind Forever Voyaging. If pressed to name a single favorite from the company’s rich catalog, I would guess that a majority of hardcore Infocom fans would likely name one of these two games. As many of you probably know already, I’m firmly in the Trinity camp myself. While A Mind Forever Voyaging is a noble experiment that positively oozes with Steve Meretzky’s big old warm-and-fuzzy heart, it’s also a bit mawkish and one-note in its writing and even its themes. It’s full of great ideas, mind you, but those ideas often aren’t explored — when they’re explored at all — in all that thoughtful of a way. And I must confess that the very puzzleless design that represents its most obvious innovation presents something of a pacing problem for me. Most of the game is just wandering around under-implemented city streets looking for something to record, an experience that leaves me at an odd disconnect from both the story and the world. Mileages of course vary greatly here (otherwise everyone would be a Trinity person), but I really need a reason to get my hands dirty in a game.

One of the most noteworthy things about Trinity, by contrast, is that it is — whatever else it is — a beautifully crafted traditional text adventure, full of intricate puzzles to die for, exactly the sort of game for which Infocom is renowned and which they did better than anyone else. If A Mind Forever Voyaging is a fascinating might-have-been, a tangent down which Infocom would never venture again, Trinity feels like a culmination of everything the 18 games not named A Mind Forever Voyaging that preceded it had been building toward. Or, put another way, if A Mind Forever Voyaging represents the adventuring avant garde, a bold if problematic new direction, Trinity is a work of classicist art, a perfectly controlled, mature application of established techniques. There’s little real plot to Trinity; little character interaction; little at all really that Infocom hadn’t been doing, albeit in increasingly refined ways, since the days of Zork. If we want to get explicit with the comparisons, we might note that the desolate magical landscape where you spend much of the body of Trinity actually feels an awful lot like that of Zork III, while the vignettes you visit from that central hub parallel Hitchhiker’s design. I could go on, but suffice to say that there’s little obviously new here. Trinity‘s peculiar genius is to be a marvelous old-school adventure game while also being beautiful, poetic and even philosophically profound. It manages to imbed its themes within its puzzles, implicating you directly in the ideas it explores rather than leaving you largely a wandering passive observer as does A Mind Forever Voyaging.

To my thinking, then, Trinity represents the epitome of Infocom’s craft, achieved some nine years after a group of MIT hackers first saw Adventure and decided they could make something even better. There’s a faint odor of anticlimax that clings to just about every game that would follow it, worthy as most of those games would continue to be on their own terms (Infocom’s sense of craft would hardly allow them to be anything else). Some of the Imps, most notably Dave Lebling, have occasionally spoken of a certain artistic malaise that gripped Infocom in its final years, one that was separate from and perhaps more fundamental than all of the other problems with which they struggled. Where to go next? What more was there to really do in interactive fiction, given the many things, like believable characters and character interactions and parsers that really could understand just about anything you typed, that they still couldn’t begin to figure out how to do? Infocom was never, ever going to be able to top Trinity on its own traditionalist terms and really didn’t know how, given the technical, commercial, and maybe even psychological obstacles they faced, to rip up the mold and start all over again with something completely new. Trinity is the top of the mountain, from which they could only start down the other side if they couldn’t find a completely new one to climb. (If we don’t mind straining a metaphor to the breaking point, we might even say that A Mind Forever Voyaging represents a hastily abandoned base camp.)

Given that I think Trinity represents Infocom’s artistic peak (you fans of A Mind Forever Voyaging and other games are of course welcome to your own opinions), I want to put my feet up here for a while and spend the first part of this new year really digging into the history and ideas it evokes. We’re going to go on a little tour of atomic history with Trinity by our side, a series of approaches to one of the most important and tragic — in the classical sense of the term; I’ll go into what I mean by that in a future article — moments of the century just passed, that explosion in the New Mexico desert that changed everything forever. We’ll do so by examining the same historical aftershocks of that “fulcrum of history” (Moriarty’s words) as does Trinity itself, like the game probing deeper and moving back through time toward their locus.

I think of Trinity almost as an intertextual work. “Intertextuality,” like many fancy terms beloved by literary scholars, isn’t really all that hard a concept to understand. It simply refers to a work that requires that its reader have a knowledge of certain other works in order to gain a full appreciation of this one. While Moriarty is no Joyce or Pynchon, Trinity evokes huge swathes of history and lots of heady ideas in often abstract, poetic ways, using very few but very well-chosen words. The game can be enjoyed on its own, but it gains so very much resonance when we come to it knowing something about all of this history. Why else did Moriarty include that lengthy bibliography? In lieu of that 40-item reading list, maybe I can deliver some of the prose you need to fully appreciate Moriarty’s poetry. And anyway, I think this stuff is interesting as hell, which is a pretty good justification in its own right. I hope you’ll agree, and I hope you’ll enjoy the little detour we’re about to make before we continue on to other computer games of the 1980s.

(This and the next handful of articles will all draw from the same collection of sources, so I’ll just list them once here.

On the side of Trinity the game and Infocom, we have, first and foremost as always, Jason Scott’s Get Lamp materials. Also the spring 1986 issue of Infocom’s newsletter, untitled now thanks to legal threats from The New York Times; the September/October 1986 and November 1986 Computer Gaming World; the August 1986 Questbusters; and the August 1986 Computer and Video Games.

As far as atomic history, I find I’ve amassed a library almost as extensive as Trinity‘s bibliography. Standing in its most prominent place we have Richard Rhodes’s magisterial “atomic trilogy” The Making of the Atomic Bomb, Dark Sun, and Arsenals of Folly. There’s also Command and Control by Eric Schlosser; The House at Otowi Bridge by Peggy Pond Church; The Nuclear Weapons Encyclopedia; Now It Can Be Told by Leslie Groves; Hiroshima by John Hershey; The Day the Sun Rose Twice by Ferenc Morton Szasz; Enola Gay by Gordon Thomas; and Prompt and Utter Destruction by J. Samuel Walker. I can highly recommend all of these books for anyone who wants to read further in these subjects.)

Duncan Stevens

January 7, 2015 at 7:17 pm

Looking forward to these posts.

One other book that doesn’t deal primarily with the Trinity test but that does capture something of the spirit of the early atomic age is Operation Crossroads: The Atomic Tests at Bikini Atoll. In particular, the book captures the total insouciance about radiation that characterized the early testing; ships were anchored in the Bikini lagoon during the first test, for example, and after the detonation the crews were sent right back onto those ships that hadn’t sunk to, you know, scrub things down a bit.

I should note that the author is a lawyer who represented the natives of Bikini Atoll for more than 30 years in their (ultimately unsuccessful) efforts to obtain compensation for the irradiation of the atoll (which persists to this day, and is expected to persist for at least another 30 years or so). I worked with him on that representation in its last few years.

Sniffnoy

January 7, 2015 at 9:29 pm

Nitpicking: “Twisting the tale” should be “twisting the tail”.

Jimmy Maher

January 8, 2015 at 6:53 am

Thanks!

FilfreFan

April 30, 2016 at 6:27 pm

Bereft of context, “twisting the tail” brought to mind the not-unrelated story of Louis Alexander Slotin, slain by the Demon Pile after “tickling the tail” of the dragon. He might have thought the better of it, as that same Demon Pile had already taken the life of his colleague, Harry K. Daghlian Jr., just a year or so earlier.

FilfreFan

May 1, 2016 at 12:08 am

LOL, when I posted, I had only read this far and didn’t imagine that this comment would be well covered in future posts.

*Sigh*

Sorry for the duplication.

Lisa H.

January 8, 2015 at 12:37 am

Trinity definitely landed among my favorites once I was old enough to really understand it.

You can watch on a computer as animated neurons blast heavy isotopes to smithereens.

Neutrons, surely, not “neurons”? Or is this error in the original?

Jimmy Maher

January 8, 2015 at 6:52 am

Nope, that was mine. Thanks!

Asterisk

January 8, 2015 at 8:38 am

Nitpick: Moriarty’s visit in July of 1985 would have coincided with the fortieth, not the thirtieth, anniversary of the Trinity tests.

Jimmy Maher

January 8, 2015 at 8:50 am

Right you are. Thanks!

Xerxes

January 8, 2015 at 1:56 pm

A single fusion device could be “thousands of kilotons of thermonuclear weapons”, so that’s not a very impressive turn of phrase. At peak, the Soviets probably had about 10 million kilotons.

Jimmy Maher

January 8, 2015 at 2:43 pm

Fair enough. Thanks!

ademct

January 8, 2015 at 5:12 pm

One of the very best satirical fiction works about the nuclear era is “This is the Way the World Ends” by James Morrow. I urge anyone who hasn’t read it to rush out and read it right now. While fiction, it also has some interesting details about the, quite literally, MAD policies of the time.

Peter Piers

December 24, 2015 at 12:18 pm

I had to read the next article to know you’re not saying those policies were insane, but actually about Mutually Assured Destruction. :)

Hanon Ondricek

January 8, 2015 at 9:00 pm

TRINITY is one of my weird favorite Infocom games ever. When I played I was young enough to have heard of the Cold War but didn’t completely understand it. Still, somehow the game hooked me. Probably for the hub landscape with a sky “the sad color of antique brass” and for teaching me what a “gnomon” is. Killing the tiny lizard was traumatic after having carried it around feeling I’d found a pet.

Lisa H.

January 8, 2015 at 9:56 pm

Oh, and one of my favorite bits from the Invisiclues, referring to the gnomon’s screw threads:

My threads clash. What do I do?

1. Get a better tailor.

Scott M. Bruner

January 8, 2015 at 10:06 pm

Having also read “Thirteen Days” as a child, and growing up on military bases, I’ve always thought perhaps the greatest proof there’s alien life is that we didn’t annihilate ourselves during the Cold War – that there exists some protective life-forms who keep shaking their head and intervening at the last minute.

I have spent a lot of time with “Trinity” – and I honestly think it’s greatest asset, as a piece of IF, is its ability to starkly affect the reader/player/interactor with its overwhelming, sense of futility. I can’t say much more with spoiling it.

It’s one of a few pieces – like AMFV – where you have to ask what the implementor is actually saying. After hearing this anecdote about Moriarty’s trip to Alamo (which I hadn’t read before), it’s amazing how well “Trinity” actually takes you into that nightmare headspace/cognitive dissonance. Strangelove as game, I guess.

The museum is called the Bradbury museum?!

Scott M. Bruner

January 8, 2015 at 10:07 pm

* its

Paul A.

March 7, 2017 at 3:43 am

The Norris E. Bradbury Science Museum, named after Oppenheimer’s successor as director of the Lab.

(And not, although this was my first thought and I’m guessing may have been yours, after the guy who wrote all those science fiction stories about humanity wiping itself out in nuclear conflagrations.)

Nate

January 11, 2015 at 7:30 pm

Interesting idea for a series. May I also suggest the other nuclear-themed games of the same era (Chernobyl comes to mind)? I don’t mean Red Storm Rising or similar non-original games.

As a kid in the 80s, I did a research paper on energy generation via nuclear reactors. My home town was farm country, so our library was out-of-date. I read quite a few Tom Swift novels from the 40s and 50s, where, in the future, everything was nuclear powered. Quite an odd alternate history.

Jimmy Maher

January 12, 2015 at 6:56 am

Interesting. I hadn’t seen that one before.

But for this series I do want to stay with Trinity. I have a lot to say about that game and a pretty good plan how to say it all…

Johannes Paulsen

January 15, 2019 at 6:32 pm

Not an alternate history at all if you live in France. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electricity_sector_in_France

ZUrlocker

January 12, 2015 at 6:08 am

Great to get the background on Trinity and I look forward to the next post.

BTW, maybe I am too much of an Infocom fanboy, but why not put together all the infocom-related blog posts (plus additional stuff on bookware) and have a whole book just on the history and impact of Infocom? I’d buy it!

Jimmy Maher

January 12, 2015 at 6:57 am

Yes, themed books on Infocom and other topics are definitely a possibility. No need to consider it until the Infocom history is finished, though…

Victor

March 29, 2019 at 8:35 pm

+1.. take my $$ please.

iPadCary

January 20, 2015 at 2:22 pm

One of THE best games ever done ….

Peter Piers

December 24, 2015 at 11:36 am

The background here is downright scary. Yes, hindsight is 20/20, but all the same, all those provocations at such a nervous time… That drill after the 007 Flight disaster… Maybe this is typical post-Atom Bomb thinking (between the Holocaust and the Atom Bomb, it’s amazing how the 20th century changed the minds and might of the world – always through war), but it seems dangerous, irresponsible, reckless, and all the other similar adjectives you want to tack on. Bravado like that gets innocents killed in the thousands.

Peter Piers

December 24, 2015 at 12:10 pm

Funny I’m still thinking about how it changed us. It’s like we were children – all through civilization, we were children, playing a game of society, taking what nature had to offer and bettering it when we could. We lived in a world of make-believe, not unlike – to get a specific example – the English class system in its heyday. WW1 and its fallout was a rude awakening there, it indicated the make-believe was over and there were, in fact, harsh realities to face and the dream couldn’t be kept up…

…and it’s like the bomb did that to the whole world. We were playing with fire, as children do – and we finally got burned. We got burned so bad we finally grew up, grew out of naïvetè and childhood. We became aware of our consequences. As an under-informed child, the term “atom children” conjured thoughts of horrors, radiation malformations, and nuclear wastelands. Now, I think I am proud to call myself, and the rest of the human race, atomic children – we have learned (hopefully), and are still learning.

CdrJameson

April 18, 2016 at 8:31 am

(I’m catching up, so sorry about commenting on an old-post)

Nitpick – References to ‘the Kensington Gardens’ and ‘the Lancaster Walk’. These places are just ‘Kensington Gardens’ and ‘Lancaster Walk’, no ‘the’ required.

I can just imagine the answer someone looking for ‘the’ Lambeth Walk would get, other than directions to Lambeth Walk.

Jimmy Maher

April 18, 2016 at 8:52 am

Thanks!

Gideon Marcus

February 3, 2017 at 5:05 am

Beautiful. Thank you so much for this. For all its flaws, Trinity is so dear to me. It was the game that brought me and my wife together, in fact.

Jimmy Maher

February 3, 2017 at 8:50 am

Wow. You should share that story, if you don’t mind.

Iain Shepherd

May 24, 2019 at 9:01 am

What Jimmy said. I would love to hear it!

DZ-Jay

March 7, 2017 at 11:42 pm

A few possible typos:

>> “Indeed, almost from the moment that Reagan had took office…”

Should that be “had taken”?

>> “… maybe they had it shot it down…”

Seems like an extra “it” in there…

Jimmy Maher

March 8, 2017 at 10:18 am

Thanks!

Oliver Naujoks, Germany

November 19, 2019 at 8:54 am

My first post here.

I just read your wonderful “Let’s tell a story together” and your articles about Trinity, a game which I loved and am in awe of. I am one of those former C-128 owners who loved the opportunity to have some Infocom games especially for my machine, even though I would still call AFMV as the artistic peak of Infocom, not Trinity.

Why I’m writing here: I recently (last year) did another playthrough of Trinity and one thing kept bugging me more than ever before: Trinity has so much to say and does some things so brillantly and then – do we really need all that zorkian stuff? So much of that? Far too much of that? It really started to bug and annoy me this time how many ridiculously tough Zork riddles I had to endure just to get to the ‘good’/atomic stuff of the game. You wrote in your essay that this is a nice sort of wraparound (my rephrasing of your words) for the subject, I’m not so sure I agree.

What do I want to say? I know that Infocom worked with the auteur-rule, but had they used more game producers and that would have been my job, I probably would have told Mr. Moriarty (Brian, not Professor): Please cut back the Zork stuff.

—

In closing, sometime it’s strange what kind of effects things have. When I played the game the first time, I was a student in Germany (and the nuclear threat was much more present in our minds) and because i was fascinated by just one quote in the game, I picked up reading Alexander Pope. :-)

Jimmy Maher

November 19, 2019 at 9:20 am

I’m not sure what you mean by “Zorkian stuff.” I’m actually not aware of any specific Zork references in Trinity. Do you mean puzzles in general? While one could certainly argue that the timing of the endgame is too tight, I think the puzzles in Trinity complement the narrative more often than not. The gnomon puzzle, the umbrella, the killing of the skink, etc., all help to bring out the game’s themes of historical time, historical culpability, and historical inevitability. I’d go so far as to call Trinity a textbook example of puzzles that serve literary ends rather than serving strictly as diversions in themselves, or merely serving to keep the player from finishing too quickly. (Although the last function can be important too in an interactive work; I’d argue that A Mind Forever Voyaging has significant pacing issues arising from its lack of puzzles. But then, I consider that game an earnest but flawed effort rather than Infocom’s masterpiece.)

Several people have pointed out in the years since I wrote these articles that I didn’t spend enough time on Trinity’s puzzle design. This is, for what it’s worth, a very fair criticism…

Oliver Naujoks

November 22, 2019 at 11:26 am

I’m afraid my phrasing “Zorkian” was misleading. What I meant was: When I play a game about the Atomic Age and the Atomic Bomb, why do I have to spend so much time wandering around another Fantasy-land(tm)?

I guess I know what Mr. Moriarty was thinking, he needed some means in the story to connect the many places and times he wanted his players to visit (like the Animus in modern Assassin’s Creed games) but a little less time spent there would have helped the game, at least for me. I love Fantasy, but I would have liked to spend more time in historical places in the game; don’t you agree?

BTW, I probably placed AMFV on such a pedestal because I played it when I was 14-15 years old. Playing it today and thinking about it, I couldn’t help but notice that the political leanings are not exactly transported in a very subtle way..

Jimmy Maher

November 22, 2019 at 11:39 am

Not really, no. Yes, the magical land serves a practical function as a conduit between times and places, but it’s not just a fantasy grab bag a la Zork. Some of the most affecting imagery in the game is found here. For instance, realizing that each mushroom represents an atomic blast, then looking off toward the horizon and seeing how the mushrooms multiply… that instant of understanding may just be the most chilling moment in the entire game. It’s imagery like this that elevates the game from a mere series of historical vignettes to something more… poetic.

Oliver

November 27, 2019 at 8:52 pm

Ok, you’re right, the scene with the mushrooms was brillant, no argument there. Maybe I’m just frustrated because I found the puzzles quite challenging when I (re-)played the game last year.

Niall

April 8, 2021 at 9:23 am

I’ve always thought that the few design flaws in this otherwise marvellous game could be solved in one single stroke: abolish the inventory limits. Change that one line of code and suddenly the player doesn’t need to preternaturally know to take the breadcrumbs, lantern, walkie-talkie and lemming to New Mexico with them (though personally, I never visit New Mexico without a lemming).

To reach the later stages of that section, only to realise that you need an object you left on the far bank of the Styx and hence have to reload yet again, was the only point of frustration in what was otherwise a perfectly fair and balanced game. (I will allow the sudden death in outer space because a) you live long enough to see the crescent moon, cluing you in immediately to the area’s purpose and b) it makes you wonder how the hell you’re going to solve what, on the face of it, seems an impossible conundrum.)

It’s curious that, while people give out endlessly about eating and sleeping loops in Infocom games, inventory limits seem to be accepted by and large. Personally, I’ve never been that bothered by having to eat something in a game. In Planetfall, I’d argue that filling up your flask each morning gives the days a bit of routine, a breakfast moment that helps place you in its world a little more.

But managing my inventory with a text parser is always a chore. Even in the Enchanter series, where you could easily make the argument that you have some magical way to have the objects float alongside you, they still force you build grim little item mounds: totems to unnecessary drudgery.

Jimmy Maher

April 8, 2021 at 9:51 am

Yes, there are a few things that could be done to make Trinity vastly more welcoming — things any good modern designer would see as fairly commonsense. Personally, I’d make failure in one of the historical vignettes bounce you back to the dreamworld to try again instead of killing you dead. And I’d make it impossible to enter a vignette without the things you’re going to need there. Neither of these steps would stretch the boundaries of the game’s magical realism unduly. Then I’d make the climax and perhaps the prologue as well run on plot time rather than clock time. While Trinity is a very cleverly structured traditional text adventure, its real identity rests in the theme it explores. It strikes me as a shame to block people from experiencing its literary qualities with a lot of petty “gamey” frustrations, but I know from comments I’ve received over the years that this had indeed happened in many cases.

Infocom evolved quickly throughout its brief lifespan, and thought more seriously about design than any 1980s adventure studio with the possible exception of Lucasfilm Games, but for all that the Imps were never entirely able to shed the old-school ethos of Zork. Trinity is an example of that: looking toward the future, but still stuck in some ways in the past.

Adam Huemer

June 21, 2025 at 7:58 pm

Instead of the pathetic “The Day After” movie I recommend the British TV education documentary “Threads” from 1984.

I advise people not to watch it when they are in bad mood. I mean it.

Ross

June 22, 2025 at 3:01 am

The AV Club used to sell a DVD that had four different government-supported films about surviving the bomb. I remember finding it amusing that the American film was basically “It’s fun and easy to survive a nuclear war” and the British film was “You might survive but the living will envy the dead” and the Canadian film was “You will probably die so tell your wife you love her now.”

wiedster

December 25, 2025 at 1:54 pm

“Trinity is the top of mountain, from which”

the top of *the* mountain?

merry christmas everyone

Jimmy Maher

December 26, 2025 at 12:34 pm

Thanks!