Activision’s first couple of years as a home-computer publisher were, for all their spirit of innovation and occasional artistic highs, mildly disappointing in commercial terms. While all of their games of this period were by no means flops, the only outsize hit among them was David Crane’s Ghostbusters. Activision was dogged by their own history; even selling several hundred thousand copies of Ghostbusters could feel anticlimactic when compared with the glory days of 1980 to 1983, when million-sellers were practically routine. And the company dragged along behind it more than psychological vestiges of that history. On the plus side, Jim Levy still had a substantial war chest made up of the profits socked away during those years with which to work. But on the minus side, the organization he ran was still too big, too unwieldy in light of the vastly reduced number of units they were moving these days in this completely different market. Levy was forced to authorize a painful series of almost quarterly layoffs as the big sales explosions stubbornly refused to come and Activision’s balance sheets remained in the red. Then came the departure of Alan Miller and Bob Whitehead to form the lean, mean Accolade, and that company’s galling instant profitability. Activision found themselves cast in the role of the bloated Atari of old, Jim Levy himself in that of the hated Ray Kassar. Nobody liked it one bit.

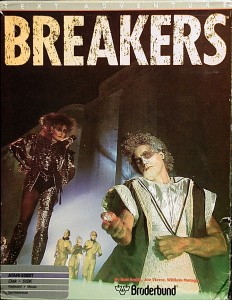

Levy and his board therefore adopted a new strategy for the second half of 1985: they would use some of that slowly dwindling war chest to acquire a whole stable of smaller developers, who would nevertheless continue to release games on their own imprints to avoid market saturation. The result would be more and more diverse games, separated into lines that would immediately identify for consumers just what type of game each title really was. In short order, Activision scooped up Gamestar, a developer of sports games. They also bought Creative Software, another tiny but stalwart industry survivor. Creative would specialize in home-oriented productivity software; ever since Brøderbund had hit it big with Bank Street Writer and The Print Shop publishers like Activision had been dreaming of duplicating their success. And then along came Infocom.

Joel Berez happened to run into Levy, accidentally or on purpose, during a business trip to Chicago in December of 1985. By this time Infocom’s travails were an open secret in the industry. Levy, by all accounts a genuine fan of Infocom’s games and, as Activision games like Portal attest, a great believer in the concept of interactive literature, immediately made it clear that Activision would be very interested in acquiring Infocom. Levy’s was literally the only offer on the table. After it dawned on them that Infocom alone could not possibly make a success out of Cornerstone, Al Vezza and his fellow business-oriented peers on Infocom’s board had for some time clung to the pipe dream of selling out to a big business publisher like Lotus, WordPerfect, or even Microsoft. But by now it was becoming clear even to them that absolutely no one cared a whit about Cornerstone, that the only value in Infocom was the games and the company’s still-sterling reputation as a game developer. However, those qualities, while by no means negligible, were outweighed in the eyes of most potential purchasers by the mountain of debt under which Infocom now labored, as well as by the worrisome shrinking sales of the pure text adventures released recently both by Infocom and their competitors. These were also very uncertain times for the industry in general, with many companies focused more on simple survival than expansion. Only Levy claimed to be able to sell his board on the idea of an Infocom acquisition. For Infocom, the choice was shaping up to be a stark one indeed: Activision subsidiary or bankruptcy. As Dave Lebling wryly said when asked his opinion on the acquisition, “What is a drowning man’s opinion of a life preserver?”

Levy was as good as his word. He convinced Activision’s board — some, especially in a year or two, might prefer to say “rammed the scheme through” — and on February 19, 1986, the two boards signed an agreement in principle for Activision to acquire Infocom by giving approximately $2.4 million in Activision stock to Infocom’s stockholders and assuming the company’s $6.8 million in debt. This was, for those keeping score, a pittance compared to what Simon & Schuster had been willing to pay barely a year before. But, what with their mountain of debt and flagging sales, Infocom’s new bargaining position wasn’t exactly strong; Simon & Schuster was now unwilling to do any deal at all, having already firmly rejected Vezza and Berez’s desperate, humiliating attempts to reopen the subject. As it was, Infocom considered themselves pretty lucky to get what they did; Levy could have driven a much harder bargain had he wanted to. And so Activision’s lawyers and accountants went to work to finalize things, and a few months later Infocom, Inc., officially ceased to exist. That fateful day was June 13, 1986, almost exactly seven years after a handful of MIT hackers had first gotten together with a vague intention to do “something with microcomputers.” It was also Friday the Thirteenth.

Still, even the most superstitious amongst Infocom’s staff could see little immediate ground for worry. If they had to give up their independence, it was hard to imagine a better guy to answer to than Jim Levy. He just “got” Infocom in a way that Al Vezza, for one, never had. He understood not only what the games were all about but also the company’s culture, and he seemed perfectly happy just to let both continue on as they were. During the due-diligence phase of the acquisition, Levy visited Infocom’s offices for a guided tour conducted, as one of his last official acts at Infocom, by an Al Vezza who visibly wanted nothing more by this time than to put this whole disappointing episode of his life behind him and return to the familiarity of MIT. In the process of duly demonstrating a series of games in progress, he came to Steve Meretzky’s next project, a risqué science-fiction farce (later succinctly described by Infocom’s newsletter as “Hitchhiker’s Guide with sex”) called Leather Goddesses of Phobos. “Of course, that’s not necessarily the final name,” muttered Vezza with embarrassment. “What? I wouldn’t call it anything else!” laughed a delighted Levy, to almost audible sighs of relief from the staffers around him.

Levy not only accepted but joined right in with the sort of cheerful insanity that had always made Vezza so uncomfortable. He cemented Infocom’s loyalty via his handling of the “InfoWedding” staffers threw for him and Joel Berez, who took over once again as Infocom’s top manager following Vezza’s unlamented departure. A description of the blessed nuptials appeared in Infocom’s newsletter.

In a dramatic affirmation of combinatorial spirit, Activision President James H. Levy and Infocom President Joel M. Berez were merged in a moving ceremony presided over by InfoRabbi Stuart W. Galleywitz. Infocommies cheered, participated in responsive readings from Hackers (written by Steven Levy — no relation to Jim), and threw rice at the beaming CEOs.

Berez read a tone poem drawn from the purple prose of several interactive-fiction stories, and Levy responded with a (clean) limerick.

The bride wore a veil made from five yards of nylon net, and carried artificial flowers. Both bride and groom wore looks of bemused surprise.

After a honeymoon at Aragain Falls, the newly merged couple will maintain their separate product-development and marketing facilities in Mountain View, California, and Cambridge, Massachusetts (i.e., we’ll still be the Infocom you know and love).

Queried about graphics in interactive-fiction stories, or better parsers in Little Computer People, the happy couple declined comment, but smiled enigmatically.

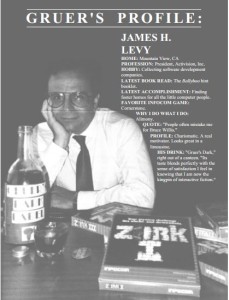

Soon after, Levy submitted to a gently mocking “Gruer’s Profile” (a play on a long-running advertising series by Dewar’s whiskey) prepared for the newsletter:

Hobby: Collecting software-development companies.

Latest Book Read: The Ballyhoo hint book.

Latest Accomplishment: Finding foster homes for all the Little Computer People.

Favorite Infocom Game: Cornerstone.

Why I Do What I Do: Alimony.

Quote: “People often mistake me for Bruce Willis.”

Profile: Charismatic. A real motivator. Looks great in a limousine.

His Drink: “Gruer’s Dark,” right out of a canteen. “Its taste blends perfectly with the sense of satisfaction I feel in knowing that I am now the kingpin of interactive fiction.”

Levy seemed to go out of his way to make the Infocom folks feel respected and comfortable within his growing Activision family. He was careful, for instance, never to refer to this acquisition as an acquisition or, God forbid, a buy-out. It was always a “merger” of apparent equals. The recently departed Marc Blank, who kept in close touch with his old colleagues and knew Levy from his time in the industry, calls him today a “great guy.” Brian Moriarty considered him “fairly benign” (mostly harmless?), with a gratifying taste for “quirky, interesting games”: “He seemed like a good match. It looked like we were going to be okay.”

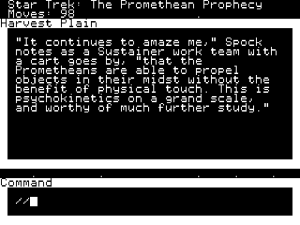

This period immediately after the Activision acquisition would prove to be an Indian summer of sorts between a very difficult period just passed and another very difficult one to come. In some ways the Imps had it better than ever. With Vezza and his business-oriented allies now all gone, Infocom was clearly and exclusively a game-development shop; all of the cognitive dissonance brought on by Cornerstone was at long last in the past. Now everyone could just concentrate on making the best interactive fiction they possibly could, knowing as they did so that any money they made could go back into making still better, richer virtual worlds. Otherwise, things looked largely to be business as usual. The first game Infocom published as an Activision subsidiary was Moriarty’s Trinity, in my opinion simply the best single piece of work they would ever manage, and one which everyone inside Infocom recognized even at the time as one of their more “special” games. As omens go, that seemed as good as they come, certainly more than enough to offset any concerns about that unfortunate choice of Friday the Thirteenth.

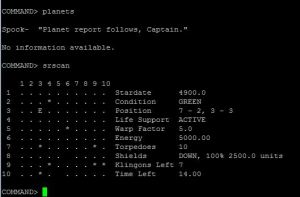

Activision’s marketing people did almost immediately offer some suggestions — and largely very sensible ones — to Infocom. Some of these Mike Dornbrook’s marketing people greeted with open arms; they were things that they had been lobbying for to the Imps, usually without much success, for years now. Most notably, Activision strongly recommended that Infocom take a hard look at a back catalog that featured some of the most beloved classics in the young culture of computer gaming and think about how to utilize the goodwill and nostalgia they engendered. The Zork brand in particular, still by far the most recognizable in Infocom’s arsenal, had been, in defiance of all marketing wisdom, largely ignored since the original trilogy concluded back in 1982. Now Infocom prepared a pair of deluxe limited-edition slip-cased compilations of the Zork and Enchanter trilogies designed not only to give newcomers a convenient point of entry but also, and almost more importantly, to appeal to the collecting instinct that motivated (and still motivates) so many of their fans. Infocom had long since learned that many of their most loyal customers didn’t generally get all that far in the games at all. Some didn’t even play them all that much. Many just liked the idea of them, liked to collect them and see them standing there on the shelf. Put an old game in a snazzy new package and many of them would buy it all over again.

Infocom also got to work at long last — in fact, literally years after they should have in Dornbrook’s view — on a new game to bear the Zork name. While they were at it, they assigned Meretzky to bring back Infocom’s single most beloved character, the cuddly robot Floyd, in the sequel to Planetfall that that game’s finale had promised back in 1983 — just as soon as he was done with Leather Goddesses, that is, a game for which Infocom, in deference to the time-honored maxim that Sex Sells, also had very high hopes.

The Infocom/Activision honeymoon period and the spirit of creative and commercial renewal it engendered would last barely six months. The chummy dialogue between these two offices on opposite coasts would likewise devolve quickly into decrees and surly obedience — or, occasionally, covert or overt defiance. But that’s for a future article. For now we’ll leave Infocom to enjoy their Indian summer of relative content, and begin to look at the games that this period produced.

(Largely the usual Infocom sources this time out: Jason Scott’s Get Lamp interviews and Down From the Top of Its Game. The Dave Lebling quote comes from an interview with Adventure Classic Gaming. The anecdote about Vezza and Levy comes from Steve Meretzky’s interview for Game Design, Theory & Practice by Richard Rouse III.

Patreon supporters: this article is a bit shorter than the norm simply because that’s the length that it “wanted” to be. Because of that, I’m making it a freebie. In the future I’ll continue to make articles of less than 2500 words free.)