For a brief moment there circa 1981, it looked like Softporn was going to spawn a whole new genre of sexy software. Following that game’s release and its massive-by-the-standards-of-1981 commercial success, others rushed to jump on the bandwagon, and the phrase “bedroom hacker” suddenly took on a whole new meaning. The titles conveyed the programs’ contents pretty well: Bedtime Stories, Dirty Old Man, Encounter, Zesty Zodiacs. Those wanting to get right down to business could presumably buy the straightforwardly named Sex Disk, while those more into foreplay could pick up Wanna Play Footsie?. My personal favorite, which makes me laugh every time for some reason, is Pornopoly. Some ambitious entrepreneurs even formed a program-of-the-month club for adult software, The Dirty Book. Their advertisements trumpeted the microcomputer “sexplosion,” promising “bedroom programs and games geared to creative, joyful living and loving,” the “opportunity to chart your own course to greater intimacy and satisfaction in the months to come.” Virtually all of this stuff was, whatever your opinion of its subject matter, pretty low-rent in execution, managing to make Softporn, hardly a marvel of writing or programming in its own right, look downright classy. But the quality of adult software never got a chance to improve in the way of other genres because suddenly, barely a year after the sexplosion began, it was all over. It was the would-be home-computer revolution that killed it.

A near-hysteria against videogames was sweeping certain sectors of the United States at that time. This was the era when entire towns were banning videogame arcades, when the Surgeon General was claiming they “addicted children, body and soul.” Makers of home computers were eager to not only avoid being tarred with the same brush, but to capitalize on the travails of the arcades and the videogame consoles by positioning a home computer like the Commodore VIC-20 as the better, healthier family alternative to an Atari VCS. A home computer, so the ad copy claimed, was first and foremost educational, a point always backed up with glossy photos of beaming children learning math or their ABCs in front of a glowing screen. A game like Pornopoly was, to say the least, not exactly compatible with that image. Indeed, American culture as a whole was changing when it came to matters of the flesh. The Christian Right was a major force to be reckoned with in American politics following Jerry Falwell’s founding of the Moral Majority in 1979 and the major role it played in getting Ronald Reagan elected President the following year. Now public attitudes toward sex were beginning to lurch back toward the wholesome 1950s, away from the revolutionary 1960s and the free-and-easy 1970s.

And so the sexplosion petered out prematurely. Even at Sierra the dying embers of California hippie decadence that had led to that famous Softporn hot-tub cover photo were fading out as the marketers and venture capitalists rushed in. Softporn itself was pulled off the market within a couple of years of its release, despite the fact that it was still selling very well, and Roberta Williams underwent a headspinning transformation from the topless swinger on the cover of Softporn to the wholesome Great Mom behind family-friendly titles like King’s Quest, Mickey’s Space Adventure, and Mixed-Up Mother Goose. Even Electronic Arts, who dearly wanted to see software as the next big trend for with-it hipsters, were careful to stay well away from any hint of sex in their games.

But of course sex never, ever really goes away. It just goes underground. With sexy software now too hot for “legitimate” distributors or shops to handle, the latest programs were traded about for free — often via the burgeoning network of pirate bulletin-board systems — or sold via advertisements in the backs of the sorts of less-than-discerning “alternative weeklies” of which every major city seemed to have at least one specimen. The character of the programs themselves changed as well. The first generation of sexy software had been relatively staid as such things go, more akin to one of the ubiquitous soft-core couple’s manuals found in such quantity on bookstore shelves then and now than hardcore pornography. This attitude extended to intent as well as content: most of these programs were quite clearly pitched to adults who would use them to enhance a relationship or social Sexy Times. The new generation of games and programs, however, was all too obviously created by the teenage boys who were beginning to dominate amongst computer users — teenage boys who had watched their share of porn but had little to no experience with actual sex. Their audience was likewise looking for something unabashedly designed to help them get off — solo.

Amongst the earliest and the most popular of all this lot was a little charmer of a text adventure called Farmer’s Daughter. It’s about exactly the teenage fantasy its name would imply: “She’s wearing tight denim shorts and a skimpy white halter top, her nipples just about poking right through. She looks about sixteen… and willing!!!” Originally created on a Commodore 64 by a couple of teenagers named R.W. Fisher and D.W.J. Sarhan and sold through advertisements in Playboy and National Lampoon amongst other places (Fisher claims they “sold a ton”), Farmer’s Daughter was hugely played, traded, and ported within the pirate underground, enough to make it one of the most popular text adventures of all time. This was one that every teenage hacker just had to have in his collection, and thanks to its subject matter one he was much more likely to earnestly try to play than just about any other. With a claim at least as great as that of Softporn to being the urtext of a whole genre of “adult interactive fiction” — Farmer’s Daughter is actually pornographic; Softporn, despite its name, isn’t — it’s still remembered by some with nostalgia even today. In 2001, one “Despoiler” even made a new version to run on modern interactive-fiction interpreters.

Farmer’s Daughter is actually one of the subtler specimens of its type, playing out largely like just another home-grown text adventure until you get to the big climax. A more typical example of one of these blue-balled fever dreams is Mad Party Fucker: “You have been invited to a party at a huge mansion. It is rumored that whores will be there. You come there nude and ready for action.” (You’re destined for the social faux pas of the century if those “rumors” turn out not to be true and this is just an ordinary old dinner party…) The hilarity of that tagline is unfortunately undercut by the ugliness of its other part: “The object of this game is to fuck as many women as you can without getting bufu’ed by fags (contracting AIDS).”

By no means did the horn-dogs confine themselves to text. In addition to endless variants of strip poker — many of them inevitably featuring the era’s most popular pinup girl, Samantha Fox — there were all sorts of rhythmic action games on offer, of varying degrees of grossness. Have a look at the website Girls of ’64 sometime and marvel and shudder at the sheer quantity and variety of the offerings. Disgusting as so much of this stuff is, there’s also something quaint about it. In just another decade or so the arrival of the Internet in homes would mean that never again would teenage boys have to satisfy their lust with pixelated, sometimes almost indecipherable 8-bit graphics and text adventures, for God’s sake.

The respectable magazines of the trade press, not to mention the shop shelves, gave no hint of this hyperactive pornographic underground. Through the brief home-computer boom and bust of 1982 to 1985 commercial software was almost universally G-rated. Sexual content began to creep back into the software overground only in about 1986. By this time the home-computer revolution had, as we’ve noted in plenty of earlier articles, largely come and gone in the eyes of the mainstream media, leaving behind a core of committed hobbyists to which it no longer paid all that much attention. One of the first publishers to sidle back through the door this partially reopened was Jim Levy’s Activision 2.0: both Alter Ego and Portal deal with sex with a bracing frankness. Notably, neither is a “sex game” in the way of those that were once featured in The Dirty Book. They’re rather games with something to say about real life; they include sex simply because sex is a part of life. As such, their sexual content could, and often did, go entirely unremarked by people who didn’t actually play them.

To everyone’s surprise, the first game of the post-bust era that did happily define itself as a “sex game” came from Infocom, heretofore regarded as amongst the most literary and mature of game makers. Leather Goddesses of Phobos put its sexy content front and center in its box copy and advertisements and, most of all, in its title.

Long before Leather Goddesses of Phobos became an actual game, it was a title and a joke — or, rather, a couple of jokes. Just after their move in 1982 into their first real corporate offices on Cambridge’s Wheeler Street, Joel Berez and Marc Blank organized a little housewarming party for Infocom’s handful of staffers and board of directors as well as other intimates — among them staffers at their new G/R Copy PR agency, employees of other local software companies and distributors, even owners of nearby computer shops. Berez and Blank were, claims Steve Meretzky, “extremely hyper” about making sure it came off as the perfect coming-out event for the growing company, despite the fact that just a few dozen outsiders were actually attending. In the offices’ central room was a big chalkboard listing all of Infocom’s modest catalog of just a few adventure games and the computers for which each was available. Always the jokester, Meretzky crept over to the chalkboard just before the party started and added an entry for Leather Goddesses of Phobos — “something that would be a little embarrassing but not awful.” Berez saw it minutes later and “erased it in a panic” before any of the outsiders could see it. (Berez and Meretzky actually had something of a history of this sort of thing. Meretzky, in the words of Mike Dornbrook, “always made fun of Joel. Mercilessly. But in a very humorous way…”)

Anticlimactic as its ending was, the story, and most of all the name, nevertheless passed into Infocom lore. Leather Goddesses of Phobos became the default name of any project that hadn’t yet been given a name of its own: “For years thereafter, when anyone needed to plug the name of a nonexistent game into a sentence, it would be Leather Goddesses of Phobos.” The name even made its way into a couple of real games: it’s a videotape the protagonist of Starcross watches, much to his disappointment when he finds out it’s actually “something about the history of the Terran Union”; and it’s the name of the only functioning machine in the video arcade in Wishbringer.

The other joke was almost as old. Whenever discussions came around to what sorts of games Infocom should do, to what genres they should cover, someone would inevitably suggest a porn game. At first the joke was just a flippant response, but as the company plunged into its disastrous 1985 and overall sales began to clearly trend downward it began to take on a decidedly more blackish tinge. At that year’s end, with A Mind Forever Voyaging behind him, Meretzky decided to actually do it: to make a real Leather Goddesses of Phobos — and to put sex in it. He wasn’t, mind you, suggesting a porn game per se, but rather a “racy” spoof of/tribute to the science-fiction serials of the 1930s. It wasn’t a hugely original idea in itself — the Barbarella comics and film of the 1960s had already worked this ground to good effect by making the sex that was implied in the old serials explicit — but it was fairly original as games went, and that was the real point. Knowing that the old dictum of Sex Sells is about as timeless as marketing wisdom gets and that Infocom could really use a hit right about now, marketing manager Mike Dornbrook as well as the other Imps agreed enthusiastically that it was a great idea. Al Vezza, still clinging by his fingernails to a fantasy of Infocom as a force in business software and always terrified of anything that might damage the company’s image in that quarter, was less enthusiastic, but allowed Meretzky to proceed. As a sop to sensibilities like his, Meretzky did agree to allow the player to select from three levels of naughtiness: “tame,” “suggestive,” and “lewd.” (I’m not certain if anyone in the history of the world has ever actually played Leather Goddesses on anything but “lewd.” That’s kind of the point of the game, isn’t it?)

Sex aside, with Leather Goddesses we’re back in Meretzky’s comfortable wheelhouse of zany science-fiction comedy, complete with all the puzzles that were so conspicuously missing from A Mind Forever Voyaging. It’s thus easy enough to cast Leather Goddesses as an artistic retreat for a Meretzky who had pushed the envelope too far with his previous game. Doing so would not be entirely incorrect, but it’s not precisely the whole truth either. You see, we really can’t set the sex aside quite so easily as all that. Leather Goddesses may mark a formal retreat in many ways, but in his soul Meretzky still desperately wanted to rake some mucks, to make another political statement. And while, as a playthrough of A Mind Forever Voyaging will attest, Meretzky was genuinely passionate about and committed to his political views, he was also a young creative person who, like so many young creative persons, just wanted to cause some controversy — any controversy.

A Mind Forever Voyaging dealt with some politically sensitive topics, and I was hoping that it would stir up a lot of controversy. It didn’t. Not a single flaming froth-at-the-mouth letter. So I decided to write something with a little bit of sex in it, because nothing generates controversy like sex. I’m hoping to get the game banned from 7-Eleven stores. Finally, I get asked all the time, “When are you guys gonna do a graphic adventure?” Well, we won’t add pictures to our stories, so this was the only way to create a graphic adventure.

Leather Goddesses of Phobos begins with this:

Some material in this story may not be suitable for children, especially the parts involving sex, which no one should know anything about until reaching the age of eighteen (twenty-one in certain states). This story is also unsuitable for censors, members of the Moral Majority, and anyone else who thinks that sex is dirty rather than fun.

The attitudes expressed and language used in this story are representative only of the views of the author, and in no way represent the views of Infocom, Inc. or its employees, many of whom are children, censors, and members of the Moral Majority. (But very few of whom, based on last year's Christmas Party, think that sex is dirty.)

By now, all the folks who might be offended by LEATHER GODDESSES OF PHOBOS have whipped their disk out of their drive and, evidence in hand, are indignantly huffing toward their dealer, their lawyer, or their favorite repression-oriented politico. So... Hit the RETURN/ENTER key to begin!

Couched in humor as it is, this is also the most topical, baldly political statement ever to appear in an Infocom game. A Mind Forever Voyaging had at least spread a thin veneer of science-fiction worldbuilding over its political message. Not so here; Meretzky calls out the Moral Majority by name. It might perhaps be a bit hard for us today to appreciate the big stew of silliness that is Leather Goddesses of Phobos as a full-on political statement. Indeed, it can be hard not to get annoyed with the game’s intermittent tendency to pat itself on the back for an alleged edginess that strikes us today as about as transgressive as missionary sex in a private bedroom between a happily married heterosexual couple. See, for instance, this gag, obviously inspired by George Carlin’s famous “Seven Words You Can’t Say On Television” routine.

>z

Time passes...

[A warning for any Jerry Falwell groupies who are miraculously still playing: we'll be using the word "tits" in five turns or so. Please consult the manual for the proper way to stop playing.]

>z

Time passes...

[Only a few turns until the "tits" reference! Use QUIT now if you might be offended!]

>z

Time passes...

[Last warning! The word "tits" will appear in the very next turn! This is your absolutely last chance to avoid seeing "tits" used!!!]

>z

Time passes...

A hyperdimensional traveller suddenly appears out of thin air. "My sister has tremendous breasts," says the traveller and, without further explanation, vanishes, leaving only a vague trace of interdimensional ozone.

[Oh, regarding the use of "tits," we changed our mind at the last minute. Everyone agreed it was too risque.]

We owe it to the game to take a moment to try to understand just why Leather Goddesses is so inexplicably proud of itself. In 1986, the year that Leather Goddesses was released, the culture wars of the 1980s were at their peak. The previous year had given the country Senate hearings instigated by Tipper Gore’s Parents Music Resource Center and their “Filthy Fifteen” list of offending songs; the hearings would lead to a “Parental Advisory” label, the so-called “Tipper sticker,” appearing on many cassettes and CDs. Two months before Leather Goddesses‘s publication Attorney General Edwin Meese’s Commission on Pornography published a report which claimed a direct link between violent crime and access to pornography amongst a host of other dubious assertions, and which argued for stepped-up enforcement of so-called “decency standards.” The following April the Federal Communications Commission would effectively change some of those same standards in a landmark ruling that levied stiff fines on shock jock Howard Stern’s radio show; from now on it would be possible to fine radio broadcasters not just for violating a list of proscribed words but for any “language or materials that depict or describe, in terms patently offensive to community standards or the broadcast media, sexual or excretory activities or sexual organs.” Taken in the context of these events and many others, Leather Goddesses‘s self-satisfaction feels more understandable and even, in its modest way, more principled.

But what is there to say about Leather Goddesses apart from its politics? Well, Mike Dornbrook’s succinct description of the game for Infocom’s newsletter is a pretty accurate one: “Hitchhiker’s Guide with sex.” You play an ordinary citizen of Upper Sandusky, Ohio, in the year 1936 who gets abducted by the Leather Goddesses of Phobos. These same Leather Goddesses are also planning to invade Earth itself, to make of it their own “private pleasure world.” You’re to be an experiment to pave the way: “your unspeakably painful death will help our effort to enslave humanity” in some way that’s never elaborated, although you are told that it will involve “lots of lubricants, some plastic tubing, and a yak.” Luckily, you escape to hopscotch around a pulp-science-fiction version of the solar system with a sidekick you pick up along the way, trying to assemble the pieces of a “Super-Duper Anti-Leather Goddesses of Phobos Attack Machine!”

1. a common household blender

2. six feet of rubber hose

3. a pair of cotton balls

4. an eighty-two degree angle

5. a headlight from any 1933 Ford

6. a white mouse

7. any size photo of Jean Harlow

8. a copy of the Cleveland phone book

It is, to say the least, a pretty nonsensical plot, one that ultimately boils down in tried-and-true adventure-game fashion to a big treasure hunt — something the game, which spends lots of time gleefully embracing and then subverting adventure-game clichés, is well aware of.

All of those teenage boys who doubtless dived into Leather Goddesses hoping it would get them off were in for a disappointment. If we accept the common definition of pornography as any work designed primarily to sexually arouse or titillate, over and above any other artistic purpose, Leather Goddesses resoundingly fails to qualify. Its few sex scenes are purposely full of schlocky romance-novel clichés, all “hot, naked bodies,” “warm and wild feelings springing from your loins, spreading like a fiery potion through your veins” and “lustful orgasms” (is there any other kind?). The detailed play-by-play and anatomical precision that teenage boys crave is, needless to say, not to be found here. In a nod toward gender equality that you certainly wouldn’t see from the pornographic-software underground, it’s actually possible to play Leather Goddesses as either a male or a female; you select your gender at the beginning of the game by going into either the men’s or women’s restroom. The sexes of various people you encounter during the game are adjusted accordingly. The very fact that Meretzky was able to do this so seamlessly within the brutal textual constraints of the 128 K Z-Machine says a lot about just how soft-focus the sex scenes actually are.

While Meretzky gets points for making the effort to include the 30 percent or so of Infocom’s loyal customers who were females, my old Gender Studies indoctrination from university does prompt me to note that even if you choose to play as a female you’re still playing a game largely built for the male gaze. Notably, the Leather Goddesses themselves don’t change gender, and remain equally interested in you whether you play as male or female. There are a couple of obvious causes for this. One is of course that changing the Leather Goddesses to Leather Gods would have been really hard given the constraints of the Z-Machine, not to mention problematic given the name of the game. And the other is that 1980s males who were appalled by male homosexuality were often more than accepting of a bit of female-on-female action.

I find the most jarring moment in Leather Goddesses to be not one of the sex scenes but rather the first time Meretzky swears at me. His first “let’s cut the bullshit” just a few turns in feels so aggressive, so at odds with Infocom’s usual house style that it always hits me like a slap. Moreover, it somehow doesn’t feel genuine either; it feels like Meretzky is swearing at me out of a sense of obligation to the “lewd” mode, and that he’s not entirely comfortable in doing so. More successful are all of the sly double entendres that litter the text, right from the moment you walk into a restroom at the beginning of the game and find a “stool” there. They’re all about as stupid as that, but sometimes gloriously so. My favorite bit might just be the response to the standard SCORE command.

>score

[with Joe]

Unfortunately, Joe doesn't seem interested, and it takes two to tango.

When he’s not cursing or referencing sex in some way, Meretzky is giving you pretty much the game you’d expect from the guy who wrote Planetfall and co-wrote The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy: lots of broad, goofy humor, the jokes coming fast and furious, often falling flat but occasionally hitting home. The situations you get yourself into are as gloriously stupid as the puns and double entendres, and perfectly redolent of the game’s inspirations: you go wandering through the jungles of Venus; go sailing the canals of Mars; and, best of all, get into a swordfight in space where you can inexplicably talk to your opponent and where Newtonian mechanics most resoundingly don’t apply. I’d probably be a bit more excited about the humor in this and Meretzky’s other games if it hadn’t led to so many less clever imitators who held fast to the “stupid” but forgot the “glorious.” See, for example, this description of a spaceship in Leather Goddesses, which is far more anatomically explicit than anything in any of the sex scenes: “Hanging from the base of the long, potent-looking battleship are two pendulous, brimming fuel tanks.” Then compare it with its distressingly literal adaptation to graphics in the blatant but more explicit Leather Goddesses clone Sex Vixens from Space of a couple of years later.

One thing that had changed about Meretzky’s work by the time of Leather Goddesses is pointed out by passages like the one just quoted: his writing has improved, subtly but significantly. Perhaps due to his enthusiasm and the sheer pace at which he turned out work, the Meretzky of Planetfall, Sorcerer, and even A Mind Forever Voyaging could be a bit slapdash, even a bit lazy in stringing his words together from time to time. Jon Palace, Infocom’s secret weapon in so many things, did much to keep that from happening in Leather Goddesses. Palace:

I would make an attempt to point out areas where the text could be a little richer. At one point Steve just gave me a big fat printout of all the words in the game. I went through it and tried to find opportunities for adjectives or verbs that could be a little more interesting.

Leather Goddesses‘s text is indeed more interesting, with more of a “you are there” feeling, with more showing and less telling. Meretzky was grateful enough to give Palace a special public thank you for “sensualizing” his text.

Still, I remain most impressed by Meretzky as a game and puzzle designer rather than as a writer. Leather Goddesses excels here. Take all the sex and all the humor away, and it’s still just a damn fine example of adventure-game craft, the best Meretzky had yet come up with. One of its puzzles in particular, the “t-removing machine,” has rightly gone down in text-adventure lore as just possibly Meretzky’s cleverest and most memorable ever. It’s also one that could never, ever be done successfully in any other medium, and another example of an increasing interest in abstract wordplay that marked many of Infocom’s later titles. The game’s most elaborate set-piece puzzle is yet another example of an Infocom maze that isn’t really a maze in the traditional sense. That said, it might just leave you longing for the days of “twisty little passages, all alike.” What with a quickly expiring light source and the cycling series of perfectly timed actions required to stay alive, it’s certainly the most polarizing of the puzzles, infuriating to a certain sort of player who considers it just tedious busywork and delightful to another type ready to pull out a pencil and paper and settle down for a nice logistical challenge. (Personally, I’m in the latter camp.) Virtually all of the other puzzles are very entertaining in less polarizing ways, logical despite the illogic of the setting and solvable, but not trivially so. It all makes for a hell of a lot of fun, even if you do mostly have to have your clothes — well, your loincloth — on.

Leather Goddesses‘s packaging became one of Infocom’s most memorable collections, arguably the last such before the company’s straitening economic circumstances began to really affect the contents of those beloved gray boxes. Meretzky always took an early and personal interest in this aspect of his games, and Leather Goddesses was no exception. He had barely begun working on the game when he had the idea of including a scratch-and-sniff card with various scents that the player would be asked to smell from time to time. Meretzky:

I got several dozen samples from the company that made the scents. Each was on its own card with the name of the scent. So one by one I had other Infocom employees come in, and I’d blindfold them and let them scratch each scent and try to identify it. That way, I was able to choose the seven most recognizable scents for the package. It was a lot of fun seeing what thoughts the various scents triggered in people, such as the person who was sniffing the mothballs and got a silly grin on his face and said, “My grandmother’s attic!”

Thus the game was designed to incorporate the seven “most recognizable” scents rather than the scents being chosen to fit the game, an unusual but not unique case of placing the feelie cart before the game horse (remember, for instance, the Wishbringer stone?). And, since you’re probably wondering: no, none of the scents were remotely sexual.

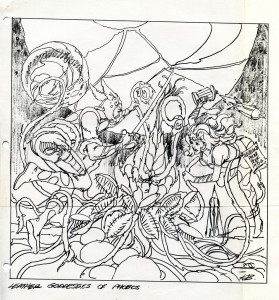

The package also included a 3-D comic complete with the requisite glasses for reading it, drawn by the same artist responsible for Trinity‘s comic, Richard Howell. (Howell would go on to have a long career in comic books.) The box cover art itself would prompt a squabble between Meretzky and Mike Dornbrook’s marketing department almost as heated as the great Spellbreaker/Mage controversy of the year before. Meretzky wanted to develop for the cover the concept drawing you see below, featuring a collection of elements from the game itself. (Thanks to Jason Scott for making this image available online.)

Dornbrook’s people, however, thought the drawing was just too busy to work on store shelves. Dornbrook:

You can’t look at a cover in isolation. You’ve got to look at a cover when it’s with a hundred other covers. Does it work on a shelf that’s crowded with covers? If it blends in, doesn’t stand out, it’s a failure, no matter how great the art is. It’s got to work as a cover!

Marketing instead opted for the cleaner, simpler design you saw earlier in this article, which also had the advantage of highlighting the marvelous name around which the whole game had been designed in the first place. A very unhappy Meretzky satirically asked to include a disclaimer in the package apologizing for the lame cover art and explaining how much better it should have been.

Leather Goddesses was released in September of 1986. Obviously feeling they might just have a sorely needed commercial winner on their hands, marketing gave the game special priority. For instance, they printed tee-shirts to pass around and sell through the Infocom newsletter, featuring the Leather Goddesses logo on the front and the slogan “A dirty mind is a terrible thing to waste” on the back. About half of the considerable fan mail the game generated was indeed of the “froth at the mouth” stripe Meretzky had been missing in response to A Mind Forever Voyaging. (Most of the other half, meanwhile, seemed to consist of complaints that the game was too tame.) A woman in Orange County, California, wandered into her local software store only to see the tee-shirt on display on the wall and, even worse, on the backs of some of the staff. She pitched a fit about the game’s title with its “deviant sexual overtones and references to bondage and other unnatural acts.” Her complaints forced an official policy change for the chain’s sixty or so stores: Leather Goddesses must be placed only on the highest shelves at the very back of the store, and could not be included in sales promotions, special in-store displays, or advertisements in any form of media — and of course staffers wouldn’t be allowed to wear their complimentary tee-shirts anymore. At least one of the big mail-order sellers, Protecto Enterprises of Illinois, declared that they were “founded on Christian principles and ethics and will not sell any product that goes against those principles”; Leather Goddesses by their lights did just that. Still, most of the most committed culture warriors in the country just weren’t paying enough attention to the relatively tiny entertainment-software market when there was so much more mainstream material in the form of music and television and films and books to rail against. Thus Meretzky would have to be satisfied with only the occasional outraged letter rather than the pitchfork-wielding mob of his dreams.

Any sales lost for reasons of outraged morality were more than made up for by the game’s sex appeal. Leather Goddesses proved to be by a factor of at least three Infocom’s biggest seller post-Activision acquisition, selling around 130,000 copies — Infocom’s last game to break six digits, their last to qualify as a genuine hit, and their first and last to prove that Sex Sells was as true in computer games as it was in any other media. It lands just below Wishbringer on Infocom’s all-time sales chart, their sixth best-selling game overall. At least one of the fans it attracted may have horrified Meretzky: Tom Clancy, technothriller author and noted friend of the Reagan administration. “I’d like to meet whoever wrote that,” he said in an interview. “I just don’t know what asylum to go to.”

The milestones in general start to get more melancholy now as we move into the latter stages of Infocom’s history. There’s one more we should mention in the case of Leather Goddesses, over and above “last 100,000 seller” and “last hit.” It marked also the last time that Infocom would have a significant part in, for lack of a better word, the conversation inside the computer-game industry at large. Other publishers took note of Leather Goddesses‘s success. With the industry’s sexual taboo at least partially broken thanks to Infocom and (to a lesser extent) Activision, sex on the computer would begin to cautiously poke its head back up out of the underground again. We’ll see plenty of evidence of that in future articles.

Like Hitchhiker’s, Leather Goddesses advertises a sequel in its finale that the original Infocom would never deliver: Gas Pump Girls Meet the Pulsating Inconvenience from Planet X. (A graphic adventure by that name would be designed by Meretzky and released by Activision under the Infocom label well after the original company was dissolved.) Too bad the series barely got started, because the already planned title of a third game might have really riled up some sensitive souls: Diesel Dikes of Deimos.

(As usual, Jason Scott’s Get Lamp interviews were invaluable to this article. Steve Meretzky is also interviewed at length in Game Design Theory and Practice by Richard Rouse III. Also useful: the October 1987 and July 1988 Computer Gaming World, and the Summer 1986 edition of Infocom’s Status Line newsletter. The Dirty Book advertisement is from the September 1982 Kilobaud.)