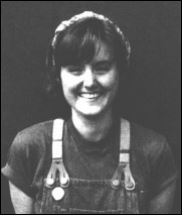

Amy Briggs first discovered text adventures during the early 1980s, when she was a student at Macalester University in her home state of Minnesota. Her boyfriend there worked at the local computer store, and introduced her to the joys of adventuring via Scott Adams’s Ghost Town. But she only became well and truly smitten — with text adventures, that is — when he first booted up a Zork for her. The pair were soon neglecting their studies to stay up all night playing on the computer.

After graduating with a degree in English and breaking up with the boyfriend, Briggs found herself somewhat at loose ends, asking that question so familiar to so many recent graduates: “What now?” Deciding that six months spent back at home with her parents was more than enough, she greeted 1985 by moving to Boston, which made for a convenient location for seeking a fortune of a type still undetermined since she had a sister already living there. Only half jokingly, she told her friends and family just before she left that if all else failed she could always go to work for Infocom.

Lo and behold, she opened the Boston Globe for the first time to find two want ads from that very company, one looking for someone to test games and the other for someone to do the same for some mysterious new business product. Briggs, naturally, wanted the games gig. Straining just a bit too hard to fit in with Infocom’s well-established sense of whimsy, she wrote a cover letter she would later “blush about,” most of all for her inexplicable claim that she had “a ridiculous sense of the sublime.” Despite or because of the cover letter, she got an interview one week later — she “stumbled out something incomprehensible” when asked about the aforementioned “ridiculous sense of the sublime” — and got a job as a game tester two weeks after that. As she herself admits, she “just walked into it,” the luckiest text-adventure fan on the planet who arrived at just about the last conceivable instant that would allow her to play a creative role in Infocom’s future.

She joined at the absolute zenith of Infocom’s success and ambition, with the whole company a beehive of activity in the wake of the recent launch of Cornerstone. On her first or second day, no less august a personage than Douglas Adams came through to talk about the huge success of his Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy game and to plan the next one. Her first assignment was to help pack up everything inside the dark warren that was Infocom’s Wheeler Street Offices and get it all shipped off to their sparkling new digs on CambridgePark Drive. Humble tester that she was, it felt like she had hit the big time, signed on with a company that was going to be the next big success story not just in games but in software in general.

Of course, it didn’t work out that way. Having enjoyed just a couple of months of the good times, Briggs would get to be present for most of the years of struggle that would follow. She kept her head down and kept testing games through all the chaos of 1985 and 1986 leading up to the Activision acquisition, managing to escape being laid off.

As a woman, and as a very young and not hugely assertive woman at that, Briggs was in a slightly uncomfortable spot at Infocom, one to which many of my female readers at least can probably relate. Infocom was not, I want to emphasize, an openly or even unconsciously misogynistic place. On the contrary, it was a very progressive place in most ways by the standards of the tech industry of the 1980s. But nevertheless, it was dominated by white males with big personalities, strong opinions, and impressive resumes. Very few who didn’t fit that profile would ever have much to say about the content of Infocom’s games. (Discounting outside testers, about the only significant female voice that comes to mind other than that of Briggs is Liz Cyr-Jones, who came up with the premise and title for Hollywood Hijinx and made contributions to many other games as one of Infocom’s most long-serving, valued, and listened-to in-house testers.) Briggs needed someone in her corner, “pushing me and showing me how to do everything from compiling ZIL to insisting that I be taken seriously.”

None other than Steve Meretzky stepped forward to fill that role. He saw a special creative spark in Briggs quite early, when she helped test his labor of love A Mind Forever Voyaging and just got what he was trying to do in a way that many other testers, still stuck in the mindset of points for treasures, didn’t. He proved instrumental in what happened next for Briggs. When she told him that she’d like to become an Imp herself someday, he introduced her to ZIL. She started working on a little game of her own for two or three hours after work in the evenings and often all day on the weekends. Like the generations of hobbyist text-adventure authors who have set their first game in their apartments, Briggs elected to begin with what she knew, the story of a tester finding bugs and taking them back to the Imp in charge. But because it was after all adventure games that she wanted to write, she muddled up this everyday tale with Alice in Wonderland: the bugs in questions were literal, metamorphosed critters, and the Imp was a caterpillar smoking a hookah.

In the fall of 1986, a call that was destined to be the last of its type went through the Infocom ranks, for a new Imp to help maintain the ambitious release schedule being pushed by Activision in the wake of the acquisition. Meretzky, showing himself to be far less sanguine on Infocom’s future prospects than he let on in public interviews, told Briggs that she should do her best to get it because “after this hiring there’s not going to be another Imp hired until one of us dies.” Along with a quiet word or two from Meretzky, her testing experience and the sample game she had been tinkering with for the last year were enough to convince management to give her a shot. Before the year was out she was an Imp, given a generous nine months — thanks to her being new on the job and all — to write, polish, and release her first game. What said first game would be was, within reason, to be left up to her.

The plan she came up with was a humdinger. She wanted to write an interactive romance novel, much like the literary guilty pleasures she had been addicted to ever since she was a teenager. Marketing immediately liked the idea of having Infocom’s first game with an explicitly female protagonist be written by a woman, saw great possibilities for opening up a “whole new market” with a game that should have huge appeal to female players. Infocom had halfheartedly pursued a similar idea before, entering into talks with a mid-list romance-novel author about a possible collaboration, only to see them peter out in the wake of the chaos wrought by Cornerstone and an evolving feeling that such partnerships with non-interactive authors usually didn’t work out all that well anyway. Now, though, they were happy to revisit the idea via a game helmed by an author who, if admittedly unproven, had been steeped in interactive fiction as well as romance fiction for quite some time now.

Meretzky, for his part, was much less bullish on the idea. A romance game must revolve around character interaction in a way that he, experienced Imp that he was, knew would be incredibly hard to pull off. Indeed, in some ways it marked the most ambitious concept anyone at Infocom had mooted since his own A Mind Forever Voyaging. And being a new, unproven Imp, Briggs would not even be given the luxury of the Interactive Fiction Plus format; her game would have to fit into the standard, aged 128 K Z-Machine. Meretzky’s advice was to do something else first and then circle back to the idea, much as Brian Moriarty had agreed to write Wishbringer before tackling his dream project Trinity. Perhaps sensing already that there might not be enough time left for that, perhaps just feeling stubborn, Briggs for once rejected his advice and pressed ahead with her original plan. Her reason for doing so was about as good as they come: this would be the Infocom game that she had always wanted to play.

Steeped sufficiently in romance novels to have become something of a scholar of the genre, Briggs had long since divided the books she read into four categories: contemporary romances; Gothic romances in the tradition of Jane Eyre and Rebecca; historical romances, or “bodice rippers,” with “lurid sex-filled plots in historical settings”; and the more subdued Regency romances in the tradition of Jane Austen, as much comedies of manners as stories of love and lust. She decided that she wanted to make her game a cross between a Regency novel, her personal favorite category, and an historical romance, with “more action than a Regency but less sex than an historical.” Whatever else it was, her game would still be an adventure game, and thus the emphasis on action seemed necessary. As for the lack of explicit sex, Briggs wasn’t suited by temperament to writing lurid sex scenes any more than Infocom was interested in publishing them — not to mention the complications of trying to craft interactive sex in a medium that struggled to depict even the most basic conversation.

Looking for an historical milieu, Briggs settled on the age of Caribbean piracy. Like Sid Meier, who was working on a very different pirate-themed game of his own 400 miles away in Baltimore, she wasn’t so interested in the historical reality of piracy as much as she was in the rich tradition of swashbuckling fiction. Many of the references she studied were doubtless the same as those being perused at the exact same time by Meier. Her actual statements about her game’s relationship to real history also echo many of Meier’s.

I already had plenty of experience with romance novels, from my reading, and I have long been interested in fashions, so I only needed to brush up on those. Pirates, though, I had to research, and sailing ships. I watched a lot of movies — Captain Blood-type movies and romantic adventures like Romancing the Stone. Plundered Hearts is about as historically accurate as an Errol Flynn movie. I tried not to be anachronistic if I could help it, but if the heroine’s hairstyle is from the wrong century or if pirates really didn’t make people walk the plank, if stretching the truth adds a lot to the story, does it really matter?

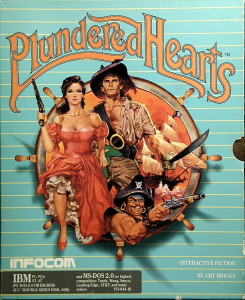

As the extract above attests, she gave her game the pitch-perfect title of Plundered Hearts. You take the role of the young Lady Dimsford, whose ship is waylaid on the high seas by a pirate who is both less and more than he seems. Captain Jamison, the legendary pirate known as “the Falcon,” is actually there to rescue you from kidnapping by the captain of your own ship, who’s in the thrall of the evil Governor Jean Lafond; Lafond already holds your father captive. Cast in the beginning in the role of damsel in distress, to survive and thwart the sinister plot against your family you’ll soon have to take a more active part in events. Along the way, you’ll need to rescue your erstwhile rescuer Captain Jamison a few times, and of course you’ll have the chance to fall in love.

As Emily Short notes in her review of the game, at times Plundered Hearts layers on the romance-novel stylings a bit thick, and with a certain knowingness that skirts the border between homage and parody, as in the heroine’s daydream that represents the very first text we see.

>SHOOT THE PIRATE

Trembling, you fire the heavy arquebus. You hear its loud report over the roaring wind, yet the dark figure still approaches. The gun falls from your nerveless hands.

"You won't kill me," he says, stepping over the weapon. "Not when I am the only protection you have from Jean Lafond."

Chestnut hair, tousled by the wind, frames the tanned oval of his face. Lips curving, his eyes rake over your inadequately dressed body, the damp chemise clinging to your legs and heaving bosom, your gleaming hair. You are intensely aware of the strength of his hard seaworn body, of the deep sea blue of his eyes. And then his mouth is on yours, lips parted, demanding, and you arch into his kiss...

He presses you against him, head bent. "But who, my dear," he whispers into your hair, "will protect you from me?"

A number of Infocom’s other more unusual genre exercises similarly verge on parody, whether as a product of sheer commitment to the genre in question or the company’s default house voice of sly, slightly sarcastic drollery. One thing that redeems Plundered Hearts, as it also does, say, many a Lovecraftian pastiche, is the author’s obvious familiarity with and love for the genre in question. And another is that even its knowing slyness, to whatever extent it’s there, departs from the usual Infocom mold. There aren’t 69,105 of anything here, no “hello, sailor” jokes, no plethora of names that start with Zorkian syllables like “Frob,” no response to “xyzzy” — all of which (and so much more like it) was beginning to feel just a little tired by 1987. Like Jeff O’Neill, another recently minted Imp who brought a fresh perspective to the job, Amy Briggs just isn’t interested in plundering the lore of Zork. Unlike O’Neill, she gives us a game that’s eminently playable. Plundered Hearts is the polar opposite of the cavalcade of insider jokes and references that is The Lurking Horror. Yes, that game certainly has its charms… but still, new blood feels more than welcome here. Plundered Hearts really does feel like it wants to reach out to new players rather than just preach to the choir.

Yet at the same time that it’s so uninterested in so many typical Infocom tropes, Plundered Hearts might just be the best expression — ever — of the Infocom ideal of interactive fiction. The backs of their boxes had been telling people for years that interactive fiction was like “waking up inside a story.” Still, the majority of Infocom games stay far, far away from that ideal. Some, like Hollywood Hijinx and Nord and Bert, are little more than a big pile of puzzles built around a broad thematic premise. Others, ranging from Infidel to Spellbreaker, give you a dash of story in the beginning and a dab of story in the end, with a long, long middle filled with lots of static geography to explore and yet more puzzles to solve. Even Infocom’s two most forthrightly literary efforts, A Mind Forever Voyaging and Trinity, aren’t quite like waking up inside a story in the novelistic sense: there’s very little conventional narrative of any sort in Trinity, while for most of its length A Mind Forever Voyaging makes its hero more an observer than the star of its unfolding plot. The mysteries do offer relatively stronger narratives and more complex characters, but they’re very much cast in the classic mystery tradition of figuring out other people’s stories rather than really making one of your own.

Plundered Hearts, however, feels qualitatively different from them and almost everything else that came before. (The closest comparison in the catalog is probably Seastalker, Infocom’s only game marketed explicitly to children.) There’s a plot thrust — a narrative urgency — that’s largely missing elsewhere in the Infocom canon, coupled with many more of the sorts of things the uninitiated might actually think of when they hear the term “interactive fiction.” As you play, the plot thickens, events unfold, relationships change, characters develop and deepen, romance blossoms. In short, real, plot-related things actually happen. I don’t mean to say that this is the only way to write a compelling text adventure. Nor do I mean to say that there’s a lot of plot here by the standards of a typical novel or even novella, nor that you can do a whole lot to influence it beyond either clearing the hurdles before you and making it to the end — the game does offer a few alternate endings via a final branch — or screwing up and dying or suffering a “fate worse than death” that usually implies rape, and often a lifetime of indentured sexual servitude. What I am saying is that Amy Briggs took interactive fiction as Infocom preferred to describe it and made her best good-faith effort to live up to that ideal. And, against all the odds, it works way better than it has any right to. I recently called the Infocom ideal of interactive fiction “something of a lost cause.” Well, I should have remembered that Plundered Hearts was waiting in the wings to prove me wrong just this once. Briggs dispenses with the things she can’t easily implement, like character interaction, via quick text dumps and concentrates the interactivity on those she can. By keeping the plot constantly in motion, she distracts us from the myriad flaws in her world’s implementation.

While Plundered Hearts has plenty of puzzles, those puzzles feel more organic than in the typical Infocom game, arising directly out of the plot rather than existing for the sake of their own cleverness. They’re also a bit easier than the norm, which suits the game’s purposes fine; you don’t want to spend hours teasing out the solution to an intricate puzzle here, you want to keep the plot moving, to find out what happens next. Most of the puzzles require only straightforward, commonsense deductions based on the materials to hand and your own goals, which are always blessedly clear. Yes, were Plundered Hearts written today, there are a few things a wise author would probably do differently. The timing of the first act, when you need to keep a powder keg in the hold of your ship from exploding, is tight enough that you might need to replay it once or twice to get it right, and it’s quite easy in one or two places to leave vital objects behind (don’t forget to grab that piece of pork when you make it to St. Sinistra!). Still, this game is far friendlier as well as far more plotty than the Infocom norm, and as a result it feels surprisingly modern even today.

As with many Infocom games, particularly in the latter half of the company’s history, much of the process of developing Plundered Hearts came down to cutting out all those pieces that wouldn’t fit into the 128 K Z-Machine. Briggs says that she finished the game inside six months, and then spent the remaining three cutting, cutting, and painfully cutting some more. Impossible as it is to make any real judgments without seeing the game she started with, Plundered Hearts doesn’t feel so much like a victim of those cuts as does Dave Lebling’s nearly contemporaneous The Lurking Horror. In some ways the cutting may have improved it, made it more playable. Briggs notes that she just didn’t have the space to allow the player to go too far astray, meaning that a screw-up more often leads to immediate death — or one of those other nasty, rapey endings — rather than a walking-dead situation. There are, she admits, “a lot of deaths” in Plundered Hearts. A lot of rapes too, more than enough to make the game feel squicky if it had been written by a man. (Yes, this is a double standard. And no, I don’t feel all that motivated to apologize for it in light of the history that gave rise to it. Your mileage may obviously vary.)

In an interview published in Infocom’s The Status Line newsletter, Briggs tried to head off accusations that the game offered a retrograde depiction of gender relations by noting that “feminism does not rule out romance, and romance does not necessarily have to make women weak in the cliché sense of romance novels.” She further pointed out, rightly, that the protagonist of Plundered Hearts must soon enough take responsibility for her own fate, must turn the tables to rescue her Captain Jamison (“several times!”) and certainly can’t afford to “act as an air-head.” Not having much — okay, any — experience with romance novels, I don’t know whether or how unusual that is for the form, and thus don’t know to what degree we can label Plundered Hearts a subversion of romance-novel tropes. I do think, however, that by the time near the end of the game that it’s you, the allegedly helpless female, who comes swinging down off a chandelier to effect a rescue, the game has quite thoroughly upended the gender roles of your typical Errol Flynn movie.

Plundered Hearts and Nord and Bert, released simultaneously in September of 1987, represented the two most obvious marketing experiments in a 1987 Infocom lineup that otherwise largely played to the adventure-gaming base. These were also the two titles about which marketing had been most excited at their inception, as chances to pry open whole new demographics. By that September, however, following a punishing nine months already full of commercial disappointments, such ideas seemed like the fantasies they had probably always been. Infocom’s marketing efforts on behalf of Plundered Hearts in particular were tentative to the point of confusion, playing up the romance-novel angle on the one hand while seeking on the other to reassure the traditional adventurers that Infocom could hardly afford to lose that, really now, this wasn’t all that big a departure from Zork. And so we got this testimonial from one Judith C.: “Infocom’s first romance does the genre proud. Playing Plundered Hearts was like opening a romance novel and walking inside.” But we also got this one from Ron T.: “I was a little afraid that I wouldn’t like the game at first, being male and playing it as a female, but once you got started it was NO PROBLEM! I enjoyed it!!!”

Neither marketing angle was sufficient to make Plundered Hearts a hit. The sales of it and its release partner Nord and Bert dropped off substantially from those of the pairing of Stationfall and The Lurking Horror of just a few months previous. The final numbers for Plundered Hearts reached only about 15,500. Briggs recalls no big thrill of accomplishment at seeing her name on an Infocom box for the first time, nor even a sense of creative fulfillment at having done something so different from the Infocom norm and done it so well, only a deep disappointment at what she and Infocom’s management viewed as just another failed experiment.

Briggs’s remaining time at Infocom proved equally frustrating. While certainly not the only Imp whose most recent game had failed to sell very well, she was in a precarious position as the newest and most inexperienced of the group, with no older, more successful titles to point to as proof of her artistic instincts. In contrast to Plundered Hearts, an idea which Infocom’s management had embraced from the get-go, her new ideas got rejected one after another by a company she characterizes as now “terrified,” desperate to find “the next Hitchhiker’s” that could save them all. Management wanted games with obvious “marketing tie-ins,” but her personal interests were “geekish.” At the same time, though, they gave her little real direction in what sorts of subjects might be more marketable: “Just write us a hit.” The most retrospectively promising of her ideas, one that would seem likely to have satisfied management’s own criteria if they’d given it a chance, was a game either heavily inspired by or outright licensing Anne Rice’s vampire novels. But it came perhaps just a little too early in the cultural conversation — Rice’s books hadn’t quite yet exploded into the mainstream to help ignite the still-ongoing craze for all things vampire in popular culture — and was ultimately rejected along with all her other ideas. About the time that management started pushing her to call up Garrison Keillor to try to get a game deal out of her very tangential relationship with him — she had worked as an usher on A Prairie Home Companion during her university days, and had attended occasional potlucks and the like with the rest of the cast and crew at Keillor’s house — she decided that enough was enough.

Briggs left Infocom in mid-1988 after completing her final work for them, the “Flathead Calendar” feelie that accompanied her old mentor Steve Meretzky’s Zork Zero. She said that she was leaving to go write the Great American Novel. But like many an aspiring novelist, Briggs found the reality of writing less enchanting than the idea; the novel never happened. She jokes today that her fellow Imps set expectations a bit too high at her farewell party when they gifted her with a tee-shirt emblazoned with the words “1989 Winner of the Pulitzer Prize.” She wound up taking a PhD in Experimental and Behavioral Psychology instead, and has since enjoyed a rewarding career in academia and private industry. Her one published work of interactive fiction — for that matter, her one published creative work of any stripe — remains Plundered Hearts.

It may be a thin creative legacy, but it’s one hell of an impressive one. Other Infocom games like A Mind Forever Voyaging and Trinity may carry more thematic weight, but in terms of sheer entertainment I don’t think Infocom ever made a better game. The last game ever released for the original 128 K Z-Machine, it’s the interactive equivalent of a great beach read in all the best senses, grabbing hold quickly and just rollicking along through rapier duels, exploding powder kegs, daring waterborne escapes, secret passages, death-defying leaps, etc., all interspersed — this being an interactive romance novel, after all — with multiple costume changes, a little ballroom dancing, and a few sweaty seductive interludes sufficient to make the old bosom heave. Much as I usually shy away from the Internet’s obsession with ranking things, if I was to list my personal favorite Infocom games Plundered Hearts would have to be right there at number two, just behind Trinity. And this comes from someone who doesn’t know the first thing about romance novels.

Indeed, one of the thoroughgoing pleasures of Plundered Hearts, the gift that keeps on giving for years after you’ve played it, is watching players like me and our friend Ron T. above fall victim to its charms despite all their stoic manly skepticism. Even Questbusters‘s redoubtable William E. Carte, who in just the previous issue had declared Nord and Bert unfit for “true adventurers,” succumbed to Plundered Hearts despite being “a traditionalist and quite conservative as well.”

I must admit it bothered me a bit at first — my character being hugged and kissed by a man. After the initial scenes, however, I quickly got lost in the plot, and soon my character’s sex honestly didn’t matter. One female QB reader wrote me that she enjoyed the game and gave it to a male friend who also liked it. He particularly liked changing clothes repeatedly.

Don’t you love the sound of prejudices collapsing? I complain from time to time, doubtless more than some of you would like, about the lack of diversity in so much ludic culture. Leaving aside politics and social engineering and even concerns about simple fairness, I think that Plundered Hearts serves as a wonderful example of why diversity is something to be sought and cherished. Amy Briggs’s unique perspective resulted in an Infocom game like no other, one that gives people like me a glimpse of what people like her see in all those trashy romance novels. In a world that could use more of that sort of understanding, that can only be a good thing. But we don’t even have to go that far. In a world that can always use better and more varied games, more and more diverse game designers is the obvious best way to achieve that.

Like a number of people I’ve written about on this blog who have long since gone on to lead other lives, Amy Briggs’s own relationship to the game she wrote all those years ago is in some ways more distant than the one some of its biggest fans enjoy with it. It crops up in her life on occasions scattered enough that they always surprise, like the time that a student knocked on her door at the university where she was teaching to ask in awed tones if she was “the Amy Briggs.” He had played Plundered Hearts ten years before with his sister — young male fans, Briggs notes bemusedly, are almost always careful to make that distinction — had loved it, just wanted to say thank you. Briggs’s own memories of her brief, unlikely career as a game designer remain a mishmash of nostalgia for “the best job I’ve ever had” with the still-lingering disappointment of Plundered Hearts‘s commercial failure — a commercial failure that, at the time and even now, is all too easy for her to conflate with its real or alleged artistic shortcomings. “There are actually people who think my game is really good,” she says with more than a tinge of disbelief in her voice. Yes, Amy, there are. We think your game is very good.

(As usual with my Infocom articles, much of this one is drawn from the full Get Lamp interview archives which Jason Scott so kindly shared with me. Thanks again, Jason! Other sources include Infocom’s Status Line newsletters of Fall 1987 and Winter 1987, Questbusters of December 1987, and an XYZZY interview with Briggs.)

Peter Piers

October 23, 2015 at 11:50 am

Yes, Amy, if you’re reading this. I played Plundered Hearts about a month ago, and it IS good. It is modern, it is playable, it is enjoyable. I’m a guy and I didn’t play it with my sister and I don’t like genre fiction of this sort and I still found it the most story-like, plot-full of the Infocom games, way ahead of its time (Jimmy forgot to mention the multiple endings).

It has atmosphere, it has spirit, it has puzzles that are just right – it is SO hard to balance puzzles so they’re neither too easy nor an obstacle to the plot, in a game that’s so obviously and clearly about the plot. It has as much style as those Errol Flyn movies you had researched.

Be proud of Plundered Hearts, Amy Briggs. Be very, very proud.

Peter Piers

October 23, 2015 at 11:53 am

“(Jimmy forgot to mention the multiple endings).”

Gah, no he didn’t! I missed where he did. Sorry, Jimmy!

Allan Holland

January 8, 2020 at 4:20 am

Heat hear. Plundered Hearts is a masterpiece adored by many.

Jayle Enn

October 23, 2015 at 11:51 am

My first brush with Plundered Hearts was the Invisiclues book. They had two games splitting a book, I think the other might have been Leather Goddesses of Phobos, and I was intrigued by the reference to alternative endings near the back.

I remember enjoying it, when I played the game years later. I’m not sure how much of it I really ‘got’ at the time, with pastiches and side references being my only familiarity with the genre, so now I’m inclined to see if I can find and get my old copy running.

Jimmy Maher

October 23, 2015 at 12:00 pm

The other game in that pairing was Beyond Zork, for what it’s worth. Infocom’s very last InvisiClues.

Peter Piers

October 23, 2015 at 11:51 am

Hey, do any of the Imps get any revenue from the Lost Treasure of Infocom releases? Including the app? I’m guessing no, but hey, call me an optimist.

Jimmy Maher

October 23, 2015 at 11:58 am

No, afraid not. Everything went to Activision with the sale, and the Imps never worked on a royalty basis anyway, only a flat salary.

Duncan Stevens

October 23, 2015 at 12:29 pm

About the time that management started pushing her to call up Garrison Keillor to try to get a game deal out of her very tangential relationship with him

Ha! I’d never heard about that. I can’t decide whether this idea was hilariously terrible or secretly brilliant, but I’m going with the former. I mean, the whole point of Lake Wobegon is that nothing much of significance ever happens; the status quo is always there again next week. (The various sepia-toned non-happenings have *emotional* significance for the narrator and the characters, at least sometimes, but they’re generally, and I guess deliberately, highly ordinary events.) Spinning a game that anyone would care about out of that (especially given the show’s older audience) would have been essentially impossible, and I can hardly blame Briggs for quitting at that point.

Jimmy Maher

October 23, 2015 at 1:01 pm

Waiting for Godot: The Adventure Game

Lisa H.

October 23, 2015 at 6:06 pm

I think you could do that too, although it would probably wind up being one of those wry one-room joke games, or something.

Rowan Lipkovits

October 24, 2015 at 5:43 am

That joke was implemented back in 1994! http://ifdb.tads.org/viewgame?id=20akruitzbk12lv4

Lisa H.

October 24, 2015 at 8:10 pm

Well there you go!

Lisa H.

October 23, 2015 at 6:05 pm

I dunno, I think in today’s IF environment you could make a Wobegon game, although it would probably be one of those more about crafting of the setting and exploration of the environment than it would be about hard puzzle-solving. But of course that’s a different beast than trying to sell it commercially in the 1980s.

Duncan Stevens

October 25, 2015 at 7:05 pm

But the setting isn’t very interesting either! Ordinary place where nothing out of the ordinary happens, that’s the whole shtick.

Duncan Stevens

October 23, 2015 at 12:43 pm

A lot of rapes too, more than enough to make the game feel squiggy if it had been written by a man.

Yeah, agree. The squickiest sequence in the game, to my mind, was the puzzle in which you had to fight off the villain’s attempts to rape you, as it was a pretty hard puzzle and hence involved a lot of failed get-raped-and-start-over attempts. (The puzzle was made harder because the tool you have that seems like the most likely way out does not, in fact, work, and the one that does is sort of buried in the scenery and requires a relatively uncommon verb to make work.) On one level, I don’t fault Briggs for including this scene; my guess is that squicking male and female players alike with an (effectively) repeated rape scene was a very deliberate way of forcing the player to confront the reality (well, romance-novel reality, but still) of rape. And it was effective, for me at least. But it wasn’t much fun.

Peter Piers

October 23, 2015 at 1:01 pm

Ditto. The one sticking point in the game, for me. I had to resort to the InvisiClues for that one, didn’t get it until the very last clue (i.e., the outright solution). It did spoil the game somewhat for me; afterwards I was not as willing to experiment as I was before, due to all of my previous failed experimenting.

But that’s just me. Once I turn to the hints, either I’ll swear then off entirely or I’ll just keep coming back; often the latter. And when compared to the rest of the puzzles (I mean, the heavy hinting of your first serious objective – stop the ship blowing up – is amazing, and without it I wouldn’t have solved that one; with that little bit of hinting, I solved it and felt clever and resourceful) it’s unfair to focus on that particular one.

It fails to bring the whole game down around it. But, it *was* a sticking point and did affect the rest of my experience.

Felix

October 23, 2015 at 2:11 pm

Tee-hee! Manly men discovering that love and adventure work the same at both ends of the gender spectrum, and that women aren’t in fact so mysterious after all. No offense, Jimmy.

But now I wonder if some male readers are similarly uncomfortable reading Interview With the Vampire, with its bisexual and overly emotional protagonist…

Felix

October 23, 2015 at 4:19 pm

In all honesty, I had a similar hesitation before reading a friend’s debut novella, simply because it’s unabashedly pornographic, and that simply isn’t my thing. But I liked it a lot, and not just because he’s my friend; it’s actually good. So, it’s worth trying something out without preconceptions now and then. Nobody says you have to finish if your first instinct turns out to have been right…

Andrew Plotkin

October 23, 2015 at 3:58 pm

I have to admit that this is one of the two core-Infocom titles that I skipped over, back in the day. (The other was Arthur.) I eventually played the LTOI edition, but of course playing games post-graduation isn’t the same as “back in the day”.

“…entering into talks with a mid-list romance-novel author about a possible collaboration…”

I don’t suppose the author’s name is accessible? If it was Elizabeth Lowell, I’m going to laugh and laugh…

Jimmy Maher

October 23, 2015 at 4:17 pm

Dave Lebling mentioned this in his Get Lamp interview. Unfortunately, he couldn’t recall her name, only could remember her being “nice.”

matt w

October 23, 2015 at 8:52 pm

What’s so funny about Elizabeth Lowell?

Andrew Plotkin

October 24, 2015 at 4:48 am

Oh, she wrote some sci-fi novels (as Ann Maxwell) which came up in discussion recently (not here).

I’m just imagining an alternate history in which Infocom published a _Fire Dancer_ adaptation as IF in 1988. But it’s thin speculation when we can’t establish who the author was in the first place.

Nathan

October 23, 2015 at 6:24 pm

You don’t actually have to take the pork; that particular puzzle has two solutions.

Taras

October 23, 2015 at 9:58 pm

One probably meaningless, but cute tangential connection Amy Briggs has with gaming history–other than her own contributions–is that she used to babysit Ron Gilbert, who of course went on to make his own swashbuckling, ahistorical, plot-driven pirate game.

Jimmy Maher

October 24, 2015 at 9:16 am

Wow. I didn’t know that. Small world.

Steve

July 5, 2017 at 4:02 am

This is amazing, if true.

Poddy

October 24, 2015 at 12:54 am

I remember the first scene very fondly, where you can wait until the pirate crashes in and the captain saves you OR NOT, take the coffer and whack the pirate over the head with it OR NOT…And the story continues, only with a slightly different understanding of your abilities and character every time such a scene unfolds. It’s possible to impress or puzzle Jamison with your resourcefulness at many spots, he’ll respond differently to what you’re wearing when you meet him, it’s just so infinitely delightful.

Jimmy Maher

October 24, 2015 at 9:17 am

I’m learning from some of these comments that Plundered Hearts is even more impressive and flexible than I realized. I didn’t know it was possible to take matters into your own hands in that first scene, and I also didn’t know it was possible to complete the game even if you leave the pork behind.

TsuDhoNimh

October 25, 2015 at 12:18 am

I played this all the way through the day after I read the article, and I agree that the game does a great job of putting you in the story and being fair to the player. I needed many hints, but I never felt that a puzzle solution was illogical or unfair. The tough puzzles mentioned in the article and in the comments were indeed tough, but at least they made sense.

The game is certainly not perfect. It drove me crazy when the game would not accept certain phrases and in the room descriptions that didn’t tell you where the exits are. I spent way too much time trying to figure out how to get past the cupboard. No amount of “push cupboard” or “squeeze through gap” or “squeeze around cupboard” would get you out. The library puzzle had me on a guess-the-exact-phrase wild goose chase as well, as did the endgame, which is impossible to get through unless you guess that you can go South out of the library, which is not in the room description at all.

Jimmy Maher

October 25, 2015 at 8:19 am

I don’t recall ever really struggling with the parser, and I definitely solved this on my own, with no hints, at least on my most recent playthrough. But granted, I have been playing a lot of Infocom games the last few years, so I perhaps have an instinct about what the parser is likely to understand, and I’m pretty good at solving adventure games in general by now. (Too bad I can’t put that skill on my CV!)

I also don’t recall struggling at all with the geography. Some of this may be a mismatch of expectations. For example, it was still pretty much expected at the time of Plundered Hearts that the player would draw a map. I always do so, using the very handy Trizbort in a window next to the interpreter. Plundered Hearts’s geography isn’t intentionally confusing, but it may be easier to see how it all fits together with a visual aid.

None of this is to say that you were playing “wrong,” of course. Just an explanation, along with the space limitations of the 128 K Z-Machine, for why a modern player may struggle a bit with a game that most contemporary players viewed as quite straightforward and very player-friendly. I’ve played so many old games since starting this blog that I may receive games more like the latter than the former by now.

Poddy

October 25, 2015 at 9:00 pm

I remember struggling with the geography as a kid, but not on later replays where habit was ingrained. The ship recognizes ‘fore’ and ‘aft’ as directions, but the game does not always use ‘enter’ intuitively. The paths around the mansion don’t strictly match up everywhere so that after going east you have to return northwest (or something quite like that) and it does requires rereading descriptions to get around.

Still, you sense a problem-solving person behind the game, who wants to play WITH you and laugh WITH you– not someone cackling at their own cleverness whenever you stumble.

TsuDhoNimh

October 26, 2015 at 5:33 pm

Clearly I should use Trizbort, which I did not know about (thanks, Jimmy!), any time I venture back into interactive fiction. Mapping is something I loved to do as a kid, but hate to do as an adult.

Steve

July 5, 2017 at 4:14 am

I completely agree about the cupboard. Navigating that area was a nightmare.

I’ve found Jimmy is quite forgiving (or just genuinely blind) if he likes a game enough. For instance, in his response to your complaint about the Library, he suggests drawing a map; except you first get to that location through a window, so the fact there is a southern doorway would never be known to you, unless explicitly stated in the description (which it wasn’t).

Torbjörn Andersson

October 27, 2015 at 10:15 pm

Being able (but not forced) to defend yourself in that early scene was one of my favorite little touches in the game, too. I was just about to post about it, when I saw you had beaten me to it!

I liked how resourceful the game made me feel as I played it, without turning me into some kind of super-woman. You do spend some time as the helpless (or not-so-helpless) victim, but it doesn’t feel out of place or character when you also get to play the rescuer.

Jake

October 24, 2015 at 10:16 pm

One of the strange things about Infocom’s canon (and, I suppose the canon of so many other influential creators) is the complete disconnect between the long-term historical assessment of a work and its contemporary reception. AMFV, Trinity, and Plundered Hearts were all frankly pretty listlessly received at the time, but nowadays I think all three garner much greater community respect than Infocom’s more well-eceived, and more conventional works. There are a lot of ways in which Plundered Hearts is straight-up good craft (the story/puzzle integration, the writing, most of the mechanics) and a few respects in which it was actively innovative (the genre experimentation, the highly characterized protagonist).

It’s a shame that Amy Briggs came so late to Infocom that it wasn’t the same sort of idyll it was for the long-timer Imps, but it’s good that those occasional props she gets from people who recognize her name make it clear that, even if she only got one shot at a game, it was a damn good shot.

Jimmy Maher

October 25, 2015 at 8:09 am

I think it’s important to remember that Infocom for much of the company’s existence all but personified mainstream adventure gaming. I wrote at some point a long time ago that those who made text adventures during the 1980s can be divided into two categories: those using text only because graphics weren’t possible, and those who saw the text adventure as a worthwhile creative form unto itself — who, in other words, *willfully* chose it over other alternatives. Sierra is the classic example of the former category; Infocom, if not 100 percent an example of the latter — they would have started including graphics of some sort by the mid-1980s if resources and technology had allowed — certainly were enraptured with interactive fiction as a form unto itself in a way matched by only a few of their peers. It’s to their huge credit that they continued to experiment with more textured, literary works throughout their lifetime, when most of the gaming public would have been perfectly happy for them to just keep making Zorks and long after such experimentation had proved itself to be less than hugely rewarding commercially.

I think we can also largely divide players into the same two categories. Those who have stuck with the format past its commercial collapse are looking for something a bit different than were most of their peers during the 1980s. Thus the positive critical consensus toward games that were often dismissed back in the day.

Janice M. Eisen

October 26, 2015 at 2:31 am

I had been, up to this point, one of those crazy loyal fans who bought every new Infocom game as soon as it came out — except for the ones I’d tested — hell, I even bought a copy of Quarterstaff. Yet, like Zarf, I skipped this one. I hated romance novels, so I had no interest, and was even kind of offended that they thought that was the way to market to women. After seeing what a high opinion you had of the game, I pulled it up in Lost Treasures and played through it.

I think I’d have been disappointed if I had bought it back in the day. For all that I kept trying to convince non-players of the literary merits of Trinity, I wanted my crossword puzzle as well. You’re right that it’s very playable — I only had to resort to the InvisiClues a couple of times — and highly polished, though I had a couple of guess-the-verb moments, but it’s also very easy. If there had been a marketing genius at the company, maybe they could have sold it to romance fans and hoped to get a few of them hooked, but I can’t imagine how, and it was, sadly, too late anyway.

I’m sorry Amy had such an unfortunate experience, since she was clearly talented. Like so much in the waning years of Infocom, what a waste!

Duncan Stevens

October 26, 2015 at 7:12 pm

One other notable thing about Plundered Hearts: more than in any other Infocom game, the PC has a personality and isn’t just the player’s avatar. There are things she will and won’t do, her emotional reaction to specific events is thoroughly described (and not just the big ones–“You haven’t been to a ball in months!”), and others react to her as a person (well, okay, some of them) rather than just someone who triggers events. Some other Infocom games had given the PC a name, but that was about it–if there was any moment when Watson or Arthur acted as something more than a faceless avatar, I sure don’t remember it.

To be sure, this could have been more consistently done, or at least there are certain aspects of the story that your character could have reacted to a tad more strongly. Escaping crocodiles, fighting off rapists, etc. Later IF games would do more with this. But it was a start.

Lisa H.

October 27, 2015 at 12:15 am

if there was any moment when Watson or Arthur acted as something more than a faceless avatar, I sure don’t remember it.

Which Activision then lampshaded in Zork: Grand Inquisitor by having the player actually be called “Ageless, Faceless, Gender-Neutral, Culturally Ambiguous Adventure Person”.

Jimmy Maher

October 27, 2015 at 3:28 pm

I think there are other Infocom games that do some of this, although not as well or as consistently. There are some off-hand remarks in the early stages of Infidel that let you know the protagonist is kind of a jerk, and in the opening act of Planetfall Meretzky beats the loser-with-a-mop drum pretty hard. Both characterizations kind of peter out later, though. Even better examples are A Mind Forever Voyaging and especially Seastalker. The latter doesn’t tend to attract much critical attention, being usually dismissed as just Infocom’s kids game (which it of course was), but if you ask me it’s actually the game in the catalog that resembles Plundered Hearts most: heavily characterized protagonist, plot-heavy, a constant narrative momentum that keeps you always reacting to events rather than just exploring static geography at your leisure. Plundered Hearts, however, is longer, better implemented, better written, and, well, just generally *better*.

It is interesting that Infocom not only never built all that much on Seastalker but that if anything, Plundered Hearts aside, did less of this sort of heavy characterization in later games. Once again I do think this points to a difference in player expectations. As I described in my article on Infidel, lots of purists weren’t at all happy about the idea of playing a *role* in an IF game, were very much wedded to the idea that they were playing *themselves*. (As Scott Adams described his protagonists, “I am your puppet.”) Mike Berlyn is on record noting that the reaction to Infidel in particular was enough to prompt Infocom to pretty much say, “Okay, won’t be trying too much more of *that*.” Nowadays the idea of playing a character who isn’t you in an IF game is so ingrained that we don’t think twice about it — or even think at all about it for that matter.

It’s also interesting to note that graphic adventures didn’t need to go through the same process. Right from King’s Quest on they often featured strongly characterized protagonists, and to seemingly little resistance or even notice from players. I think this is down to the second-person descriptions of text adventures versus the third-person view common in most early graphic adventures (and plenty of later ones as well, of course). When Myst became popular later on and brought with it a whole slew of first-person games, the old nameless, genderless, generic adventurey person made a comeback — including, as Lisa notes, in Zork: Nemesis and Zork: Grand Inquisitor.

Duncan Stevens

October 27, 2015 at 5:05 pm

Mike Berlyn is on record noting that the reaction to Infidel in particular was enough to prompt Infocom to pretty much say, “Okay, won’t be trying too much more of *that*.”

I pulled up the quote from your Infidel article; I assume you’re thinking of this:

People really don’t want to know who they are [in a game]. This was an interesting learning process for everyone at Infocom. We weren’t really writing interactive fiction — I don’t care what you call it, I don’t care what you market it as. It’s not fiction. They’re adventure games. You want to give the player the opportunity to put themselves in an environment as if they were really there.

I wonder whether Berlyn/Infocom learned the right lesson, and whether Berlyn was accurately conveying the reaction that Infocom got. Was it that players didn’t want to be put in the shoes of a protagonist at all? Or was it that they didn’t like being put in the shoes of a really unappealing protagonist and being punished for his sins (committed prior to the game beginning)? In all likelihood, no one articulated this distinction very precisely, but they’re not the same thing, to my mind.

As for Seastalker and AMFV…I don’t think I’d call Seastalker’s protagonist heavily characterized. You learn in the feelies that you’re a brilliant young inventor, and other people treat you as part of the team, but I don’t think the game ever gives you any kind of emotional reaction to anything, hints at a personality trait, or identifies something you can or can’t do because of who you are. And in AMFV, you don’t have a personality at all in the lab and your simulated character is largely undeveloped. You’re a little more than an avatar in both games, but only a little. PH, uneven as it was in this respect, was a pretty big jump.

Jimmy Maher

October 28, 2015 at 9:58 am

Berlyn designed Infidel to provoke, and provoke it did. Players’ reactions were undoubtedly made more extreme by the fact that the protagonist was so unappealing. That said, a lot of the debate that followed — much of it described in that article — did really highlight a difference in player expectations and assumptions that feels very striking today. Infocom obviously didn’t totally reject the idea of more fleshed-out protagonists, but I do think it caused them to tread quite carefully.

In the case of Seastalker, I think that the protagonist’s personality is conveyed quite well through the tone of the writing itself. It feels like the character’s own internal monologue. Hitchhiker’s has a very distinct “parser personality” as well, but that feels not so much like Arthur’s personality as it does the *game’s*.

Much as I’m in the “brave but flawed experiment” rather than the “misunderstood masterpiece” camp when it comes to A Mind Forever Voyaging, I give it a little more credit than you do. The scenes with Perry’s wife in particular really highlighted his personality. Things like the statement (heavily paraphrased here) that she looks even more beautiful now than she did when you married her decades ago really brought Perry’s subjective impressions into play. It wasn’t done all that often, and sometimes not all that well — it was actually in the game after the supposedly “literary” AMFV, Leather Goddesses, that Meretzky’s writing started markedly improving — but it is there, and very much intentionally so. It’s unsurprising then that this was the game over which Meretzky and Briggs first bonded.

None of which is to say that Plundered Hearts didn’t significantly improve on all those earlier efforts. It is, as I wrote in the article, the game that most closely matches the ideal of interactive fiction that an uninitiated someone might expect from reading the back of an Infocom box, and its willingness to invest the protagonist with a real personality is a big part of that.

Jubal

October 28, 2015 at 4:59 am

So, there was a swashbuckling romantic adventure released in September of 1987, packed with romance, ingenious problems, affectionate references to classic stories, old Errol Flynn movies, love and romance, dashing handsome pirates, and so on, and which made little impact on release but has gone on to be much loved and very highly regarded. All of which applies equally to Plundered Hearts and The Princess Bride. There must have been something in the water.

Jimmy Maher

October 28, 2015 at 10:11 am

Plundered Hearts and The Princess Bride also apparently share a puzzle solution, according to Neil deMause in his XYZZY News interview with Amy Briggs. Briggs clarifies that she didn’t lift the puzzle from the movie but rather from a book called The Sherwood Ring by Elizabeth Marie Pope. I don’t know whether The Princess Bride lifted from the same source. In fact, I don’t even know what the puzzle in question *is*. Maybe someone more familiar with the movie — I haven’t seen it in 20 years at least — has an idea?

Duncan Stevens

October 28, 2015 at 12:25 pm

I’m guessing Neil was thinking about the goblets, though it’s a stretch to call it a common puzzle solution. But there’s a link insofar as poisoning/drugging a particular goblet does not actually solve the problem in either case.

Lisa H.

October 28, 2015 at 5:12 pm

I dunno about a common puzzle solution as such, but the “which goblet is poisoned” trope sort of feels like an old standard. Anyone else remember “The Court Jester”?

Steve

July 5, 2017 at 4:46 am

To note, the Invisiclues for this game references The Court Jester when addressing this puzzle. “The flagon with the dragon has the brew that is true…”

Amy

March 27, 2025 at 9:59 pm

If this is the “they were both poisoned; I’ve just built up a resistance to it” moment from TPB, I would like to note (SPOILER ALERT) the Dorothy L. Sayers predated that by several decades with her own “Strong Poison”.

NPC

January 4, 2016 at 7:43 am

Artistic extincts

A fate worse than death for a game designer?

Jimmy Maher

January 4, 2016 at 9:41 am

How did that go unnoticed for so long? Thanks!

Ruber Eaglenest

January 25, 2016 at 4:20 pm

This article was just marvellous. Thanks a lot!

William Hern

April 2, 2017 at 5:17 pm

Another great article – congratulations on highlighting one of the hidden gems in the Infocom collection.

You mention at the end of the piece that Plundered Hearts is available as part of the iOS “Lost Treasures of Infocom” collection. This is a great set of adventures – I’ve spent many enjoyable hours replaying the classic games.

Unfortunately Activision has not updated the app in over five years and it is likely that it will not run in the next version of iOS.

I’ve started a discussion thread about this in the Activision support forums and it would be great if others could chime in. The more supporting posts that we get, the greater the chance that Activision may listen and recompile the app so that it runs in the 64-bit iOS environment.

You can find the thread here – https://community.activision.com/t5/Activision-Support/Lost-Treasures-of-Infocom-on-iOS-needs-64-bit-support/m-p/10212843

William Hern

September 24, 2017 at 8:31 pm

Unfortunately Activision has not granted permission for the recompile of the “Lost Treasures of Infocom” and, as a result, the app will not run in iOS 11. Nor is it available in the new AppStore.

A petition has been started on change.org and I’d encourage everyone to sign it. The more signatures we get, the better the chances we have of getting someone at Activision to take notice.

https://www.change.org/p/activision-convince-activision-to-convert-their-ios-game-lost-treasures-of-infocom-to-64-bit

Steve

July 5, 2017 at 4:55 am

Ha! This claim is a bit subverted for long time readers by your insistence on bringing 21st century gender politics into your articles about the ’80s every time you get the chance. Stoic manly skepticism? I mean, come on. There’s been no evidence of that in any of your writing so far… ;)

Not to say that’s a bad thing, but your claim to the otherwise just comes off as disingenuous here. (Not to mention how it clouds perceptions of your rapturous praise of the game; did you just like the game because it was written by a female with a female protagonist? Or was it actually a good game that happened to have a female PC?)

P J Evans

April 20, 2019 at 7:41 pm

I tried to play it. But I could never get it to get past the first scene – there didn’t seem to be a way to get it to *do* anything. (It’s one of those where I want the !@#$%^&*(!!! source code.)

Wolfeye M.

September 20, 2019 at 11:46 am

I don’t like romance, but a female protagonist, who isn’t a useless damsel in distress, sounds like a nice change of pace.

But, the rape in the game is a major turn off, so I won’t play it.

Frankly, it’s *worse* if a woman writes that kind of garbage, because women, more often than not, are the victims. Why would a woman want to put another woman, even a fictional one, through that experience? Even worse, take the player right along with her? Even if it’s the fade to black, screaming in agony off screen, kind of portrayal, it’s garbage. Kills all interest I’d ever have in the game.

A shame, a real shame, because otherwise I’d have wanted to play it.

Nathanael

April 21, 2020 at 6:34 pm

Having played all the Infocom games (often using hint books and walkthroughs liberally — Wishbringer is the only one I cleared without a single hint), I have to agree. Plundered Hearts is really very good, and I would love to see more like it. I haven’t seen a modern “story oriented” game which I enjoyed as much.

Ben

February 11, 2023 at 5:10 pm

other peoples’ -> other people’s

squiggy -> squicky

for her conflate -> for her to conflate

Jimmy Maher

October 10, 2023 at 10:57 am

Thanks!

Busca

October 8, 2023 at 8:45 pm

Joe Pranevich recently covered Plundered Hearts for The Adventurers Guild, including alternate endings and cut content, and had a lot of fun with it.

On his final entry someone called / calling himself ‘John’ just left a comment this week mentioning he is doing an oral history with Amy next month for inclusion in the Archives of her alma mater and saying if anyone has any questions for her, he can probably get them answered and/or work them into the interview.

John

January 6, 2024 at 3:48 pm

Hi Busca!

The interview got pushed back a bit, but it’s happening this coming week. The IF forums yielded a fair amount of questions to work in when I asked there.

John

May 8, 2024 at 10:36 pm

Here’s that oral history I conducted with Amy!

https://contentdm.macalester.edu/digital/collection/p16903coll15/id/11/rec/1

Jimmy Maher

May 9, 2024 at 2:14 pm

That’s great. Congratulations! I look forward to watching it when I have a bit more time over the weekend.