The biggest problem with the Macintosh hardware was pretty obvious, which was its limited expandability. But the problem wasn’t really technical as much as philosophical, which was that we wanted to eliminate the inevitable complexity that was a consequence of hardware expandability, both for the user and the developer, by having every Macintosh be identical. It was a valid point of view, even somewhat courageous, but not very practical, because things were still changing too fast in the computer industry for it to work, driven by the relentless tides of Moore’s Law.

— original Macintosh team-member Andy Hertzfeld

Jef Raskin and Steve Jobs didn’t agree on much, but they did agree on their loathing for expansion slots. The absence of slots was one of the bedrock attributes of Raskin’s original vision for the Macintosh, the most immediately obvious difference between it and Apple’s then-current flagship product, the Apple II. In contrast to Steve Wozniak’s beloved hacker plaything, Raskin’s computer for the people would be as effortless to set up and use as a stereo, a television, or a toaster.

When Jobs took over the Macintosh project — some, including Raskin himself, would say stole it — he changed just about every detail except this one. Yet some members of the tiny team he put together, fiercely loyal to their leader and his vision of a “computer for the rest of us” though they were, were beginning to question the wisdom of this aspect of the machine by the time the Macintosh came together in its final form. It was a little hard in January of 1984 not to question the wisdom of shipping an essentially unexpandable appliance with just 128 K of memory and a single floppy-disk drive for a price of $2495. At some level, it seemed, this just wasn’t how the computer market worked.

Jobs would reply that the whole point of the Macintosh was to change how computers worked, and with them the workings of the computer market. He wasn’t entirely without concrete arguments to back up his position. One had only to glance over at the IBM clone market — always Jobs’s first choice as the antonym to the Mac — to see how chaotic a totally open platform could be. Clone users were getting all too familiar with the IRQ and memory-address conflicts that could result from plugging two cards that were determined not to play nice together into the same machine, and software developers were getting used to chasing down obscure bugs that only popped up when their programs ran on certain combinations of hardware.

Viewed in the big picture, we could actually say that Jobs was prescient in his determination to stamp out that chaos, to make every Macintosh the same as every other, to make the platform in general a thoroughly known quantity for software developers. The norm in personal computing as most people know it — whether we’re talking phones, tablets, laptops, or increasingly even desktop computers — has long since become sealed boxes of one stripe or another. But there are some important factors that make said sealed boxes a better idea now than they were back then. For one thing, the pace of hardware and software development alike has slowed enough that a new computer can be viable just as it was purchased for ten years or more. For another, prices have come down enough that throwing a device away and starting over with a new one isn’t so cost-prohibitive as it once was. With personal computers still exotic, expensive machines in a constant state of flux at the time of the Mac’s introduction, the computer as a sealed appliance was a vastly more problematic proposition.

Determined to do everything possible to keep users out of the Mac’s innards, Apple used Torx screws for which screwdrivers weren’t commonly available to seal it, and even threatened users with electrocution should they persist in trying to open it. The contrast with the Apple II, whose top could be popped in seconds using nothing more than a pair of hands to reveal seven tempting expansion slots, could hardly have been more striking.

It was the early adopters who spotted the potential in that first slow, under-powered Macintosh, the people who believed Jobs’s promise that the machine’s success or failure would be determined by the number who bought it in its first hundred days on the market, who bore the brunt of Apple’s decision to seal it as tightly as Fort Knox. When Apple in September of 1984 released the so-called “Fat Mac” with 512 K of memory, the quantity that in the opinion of just about everyone — including most of those at Apple not named Steve Jobs — the machine should have shipped with in the first place, owners of the original model were offered the opportunity to bring their machines to their dealers and have them retro-fitted to the new specifications for $995. This “deal” sparked considerable outrage and even a letter-writing campaign that tried to shame Apple into bettering the terms of the upgrade. Disgruntled existing owners pointed out that their total costs for a 512 K Macintosh amounted to $3490, while a Fat Mac could be bought outright by a prospective new member of the Macintosh fold for $2795. “Apple should have bent over backward for the people who supported it in the beginning,” said one of the protest’s ringleaders. “I’m never going to feel the same about Apple again.” Apple, for better or for worse never a company that was terribly susceptible to such public shaming, sent their disgruntled customers a couple of free software packages and told them to suck it up.

Barely fifteen months later, when Apple released the Macintosh Plus with 1 MB of memory among other advancements, the merry-go-round spun again. This time the upgrade would cost owners of the earlier models over $1000, along with lots of downtime while their machines sat in queues at their dealers. With software developers rushing to take advantage of the increased memory of each successive model, dedicated users could hardly stand to regard each successive upgrade as optional. As things stood, then, they were effectively paying a service charge of about $1000 per year just to remain a part of the Macintosh community. Owning a Mac was like owning a car that had to go into the shop for a week for a complete engine overhaul once every year. Apple, then as now, was famous for the loyalty of their users, but this was stretching even that legendary goodwill to the breaking point.

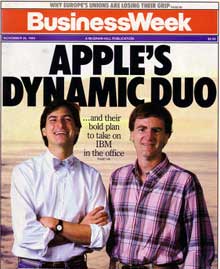

For some time voices within Apple had been mumbling that this approach simply couldn’t continue if the Macintosh was to become a serious, long-lived computing platform; Apple simply had to open the Mac up, even if that entailed making it a little more like all those hated beige IBM clones. During the first months after the launch, Steve Jobs was able to stamp out these deviations from his dogma, but as sales stalled and his relationship with John Sculley, the CEO he’d hand-picked to run the company he’d co-founded, deteriorated, the grumblers grew steadily more persistent and empowered.

The architect of one of the more startling about-faces in Apple’s corporate history would be Jean-Louis Gassée, a high-strung marketing executive newly arrived in Silicon Valley from Apple’s French subsidiary. Gassée privately — very privately in the first months after his arrival, when Jobs’s word still was law — agreed with many on Apple’s staff that the only way to achieve the dream of making the Macintosh into a standard to rival or beat the Intel/IBM/Microsoft trifecta was to open the platform. Thus he quietly encouraged a number of engineers to submit proposals on what direction they would take the platform in if given free rein. He came to favor the ideas of Mike Dhuey and Brian Berkeley, two young engineers who envisioned a machine with slots as plentiful and easily accessible as those of the Apple II or an IBM clone. Their “Little Big Mac” would be based around the 32-bit Motorola 68020 chip rather than the 16-bit 68000 of the current models, and would also sport color — another Jobsian heresy.

In May of 1985, Jobs made the mistake of trying to recruit Gassée into a rather clumsy conspiracy he was formulating to oust Sculley, with whom he was now in almost constant conflict. Rather than jump aboard the coup train, Gassée promptly blew the whistle to Sculley, precipitating an open showdown between Jobs and Sculley in which, much to Jobs’s surprise, the entirety of Apple’s board backed Sculley. Stripped of his power and exiled to a small office in a remote corner of Apple’s Cupertino campus, Jobs would soon depart amid recriminations and lawsuits to found a new venture called NeXT.

Gassée’s betrayal of Jobs’s confidence may have had a semi-altruistic motivation. Convinced that the Mac needed to open up to survive, perhaps he concluded that that would only happen if Jobs was out of the picture. Then again, perhaps it came down to a motivation as base as personal jealousy. With a penchant for leather and a love of inscrutable phraseology — “the Apple II smelled like infinity” is a typical phrase from his manifesto The Third Apple, “an invitation to voyage into a region of the mind where technology and poetry exist side by side, feeding each other” — Gassée seemed to self-consciously adopt the persona of a Gallic version of Jobs himself. But regardless, with Jobs now out of the picture Gassée was able to consolidate his own power base, taking over Jobs’s old role as leader of the Macintosh division. He went out and bought a personalized license plate for his sports car: “OPEN MAC.”

Coming some four months after Jobs’s final departure, the Mac Plus already included such signs of the changing times as a keyboard with arrow keys and a numeric keypad, anathema to Jobs’s old mouse-only orthodoxy. But much, much bigger changes were also well underway. Apple’s 1985 annual report, released in the spring of 1986, dropped a bombshell: a Mac with slots was on the way. Dhuey and Berkeley’s open Macintosh was now proceeding… well, openly.

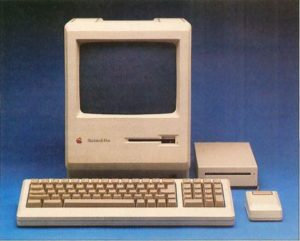

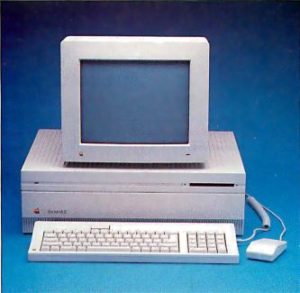

When it debuted five months behind schedule in March of 1987, the Macintosh II was greeted as a stunning but welcome repudiation of much of what the Mac had supposedly stood for. In place of the compact all-in-one-case designs of the past, the new Mac was a big, chunky box full of empty space and empty slots — six of them altogether — with the monitor an item to be purchased separately and perched on top. Indeed, one could easily mistake the Mac II at a glance for a high-end IBM clone; its big, un-stylish case even included a cooling fan, an item that placed even higher than expansion slots and arrow keys on Steve Jobs’s old list of forbidden attributes.

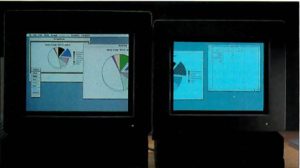

Apple’s commitment to their new vision of a modular, open Macintosh was so complete that the Mac II didn’t include any on-board video at all; the buyer of the $6500 machine would still have to buy the video card of her choice separately. Apple’s own high-end video card offered display capabilities unprecedented in a personal computer: a palette of over 16 million colors, 256 of them displayable onscreen at any one time at resolutions as high as 640 X 480. And, in keeping with the philosophy behind the Mac II as a whole, the machine was ready and willing to accept a still more impressive graphics card just as soon as someone managed to make one. The Mac II actually represented colors internally using 48 bits, allowing some 281 trillion different shades. These idealized colors were then translated automatically into the closest approximations the actual display hardware could manage. This fidelity to the subtlest vagaries of color would make the Mac II the favorite of people working in many artistic and image-processing fields, especially when those aforementioned even better video cards began to hit the market in earnest. Even today no other platform can match the Mac in its persnickety attention to the details of accurate color reproduction.

Some of the Mac II’s capabilities truly were ahead of their time. Here we see a desktop extended across two monitors, each powered by its own video card.

The irony wasn’t lost on journalists or users when, just weeks after the Mac II’s debut, IBM debuted their new PS/2 line, marked by sleeker, slimmer cases and many features that would once have been placed on add-on-cards now integrated into the motherboards. While Apple was suddenly encouraging the sort of no-strings-attached hardware hacking on the Macintosh that had made their earlier Apple II so successful, IBM was trying to stamp that sort of thing out on their own heretofore open platform via their new Micro Channel Architecture, which demanded that anyone other than IBM who wanted to expand a PS/2 machine negotiate a license and pay for the privilege. “The original Mac’s lack of slots stunted its growth and forced Apple to expand the machine by offering new models,” wrote Byte. “With the Mac II, Apple — and, more importantly, third-party developers — can expand the machine radically without forcing you to buy a new computer. This is the design on which Apple plans to build its Macintosh empire.” It seemed like the whole world of personal computing was turning upside down, Apple turning into IBM and IBM turning into Apple.

If so, however, Apple’s empire would be a very exclusive place. By the time you’d bought a monitor, video card, hard drive, keyboard — yes, even the keyboard was a separate item — and other needful accessories, a Mac II system could rise uncomfortably close to the $10,000 mark. Those who weren’t quite flush enough to splash out that much money could still enjoy a taste of the Mac’s new spirit of openness via the simultaneously released Mac SE, which cost $3699 for a hard-drive-equipped model. The SE was a 68000-based machine that looked much like its forefathers — built-in black-and-white monitor included — but did have a single expansion slot inside its case. The single slot was a little underwhelming in comparison to the Mac II, but it was better than nothing, even if Apple did still recommend that customers take their machines to their dealers if they wanted to actually install something in it. Apple’s not-terribly-helpful advice for those needing to employ more than one expansion card was to buy an “integrated” card that combined multiple functions. If you couldn’t find a card that happened to combine exactly the functions you needed, you were presumably just out of luck.

During the final years of the 1980s, Apple would continue to release new models of the Mac II and the Mac SE, now established as the two separate Macintosh flavors. These updates enhanced the machines with such welcome goodies as 68030 processors and more memory, but, thanks to the wonders of open architecture, didn’t immediately invalidate the models that had come before. The original Mac II, for instance, could be easily upgraded from the 68020 to the 68030 just by dropping a card into one of its slots.

The Steve Jobs-less Apple, now thoroughly under the control of the more sober and pragmatic John Sculley, toned down the old visionary rhetoric in favor of a more businesslike focus. Even the engineers dutifully toed the new corporate line, at least publicly, and didn’t hesitate to denigrate Apple’s erstwhile visionary-in-chief in the process. “Steve Jobs thought that he was right and didn’t care what the market wanted,” Mike Dhuey said in an interview to accompany the Mac II’s release. “It’s like he thought everyone wanted to buy a size-nine shoe. The Mac II is specifically a market-driven machine, rather than what we wanted for ourselves. My job is to take all the market needs and make the best computer. It’s sort of like musicians — if they make music only to satisfy their own needs, they lose their audience.” Apple, everyone was trying to convey, had grown up and left all that changing-the-world business behind along with Steve Jobs. They were now as sober and serious as IBM, their machines ready to take their places as direct competitors to those of Big Blue and the clonesters.

To a rather surprising degree, the world of business computing accepted Apple and the Mac’s new persona. Through 1986, the machines to which the Macintosh was most frequently compared were the Commodore Amiga and Atari ST. In the wake of the Mac II and Mac SE, however, the Macintosh was elevated to a different plane. Now the omnipresent point of comparison was high-end IBM compatibles; the Amiga and ST, despite their architectural similarities, seldom even saw their existence acknowledged in relation to the Mac. There were some good reasons for this neglect beyond the obvious ones of pricing and parent-company rhetoric. For one, the Macintosh was always a far more polished experience for the end user than either of the other 68000-based machines. For another, Apple had enjoyed a far more positive reputation with corporate America than Commodore or Atari had even well before any of the three platforms in question had existed. Still, the nature of the latest magazine comparisons was a clear sign that Apple’s bid to move the Mac upscale was succeeding.

Whatever one thought of Apple’s new, more buttoned-down image, there was no denying that the market welcomed the open Macintosh with a matching set of open arms. Byte went so far as to call the Mac II “the most important product that Apple has released since the original Apple II,” thus elevating it to a landmark status greater even than that of the first Mac model. While history hasn’t been overly kind to that judgment, the fact remains that third-party software and hardware developers, who had heretofore been stymied by the frustrating limitations of the closed Macintosh architecture, burst out now in myriad glorious ways. “We can’t think of everything,” said an ebullient Jean-Louis Gassée. “The charm of a flexible, open product is that people who know something you don’t know will take care of it. That’s what they’re doing in the marketplace.” The biannual Macworld shows gained a reputation as the most exciting events on the industry’s calendar, the beat to which every journalist lobbied to be assigned. The January 1988 show in San Francisco, the first to reflect the full impact of Apple’s philosophical about-face, had 20,000 attendees on its first day, and could have had a lot more than that had there been a way to pack them into the exhibit hall. Annual Macintosh sales more than tripled between 1986 and 1988, with cumulative sales hitting 2 million machines in the latter year. And already fully 200,000 of the Macs out there by that point were Mac IIs, an extraordinary number really given that machine’s high price. Granted, the Macintosh had hit the 2-million mark fully three years behind the pace Steve Jobs had foreseen shortly after the original machine’s introduction. But nevertheless, it did look like at least some of the more modest of his predictions were starting to come true at last.

An Apple Watch 27 years before its time? Just one example of the extraordinary innovation of the Macintosh market was the WristMac from Ex Machina, a “personal information manager” that could be synchronized with a Mac to take the place of your appointment calendar, to-do list, and Rolodex.

While the Macintosh was never going to seriously challenge the IBM standard on the desks of corporate America when it came to commonplace business tasks like word processing and accounting, it was becoming a fixture in design departments of many stripes, and the staple platform of entire niche industries — most notably, the publishing industry, thanks to the revolutionary combination of Aldus PageMaker (or one of the many other desktop-publishing packages that followed it) and an Apple LaserWriter printer (or one of the many other laser printers that followed it). By 1989, Apple could claim about 10 percent of the business-computing market, making them the third biggest player there after IBM and Compaq — and of course the only significant player there not running a Microsoft operating system. What with Apple’s premium prices and high profit margins, third place really wasn’t so bad, especially in comparison with the moribund state of the Macintosh of just a few years before.

So, the Macintosh was flying pretty high as the curtain began to come down on the 1980s. It’s instructive and more than a little ironic to contrast the conventional wisdom that accompanied that success with the conventional wisdom of today. Despite the strong counterexample of Nintendo’s exploding walled garden over in the videogame-console space, the success the Macintosh had enjoyed since Apple’s decision to open up the platform was taken as incontrovertible proof that openness in terms of software and hardware alike was the only viable model for computing’s future. In today’s world of closed iOS and Android ecosystems and computing via disposable black boxes, such an assertion sounds highly naive.

But even more striking is the shift in the perception of Steve Jobs. In the late 1980s, he was loathed even by many strident Mac fans, whilst being regarded in the business and computer-industry press and, indeed, much of the popular press in general as a dilettante, a spoiled enfant terrible whose ill-informed meddling had very nearly sunk a billion-dollar corporation. John Sculley, by contrast, was lauded as exactly the responsible grown-up Apple had needed to scrub the company of Jobs’s starry-eyed hippie meanderings and lead them into their bright businesslike present. Today popular opinion on the two men has neatly reversed itself: Sculley is seen as the unimaginative corporate wonk who mismanaged Jobs’s brilliant vision, Jobs as the greatest — or at least the coolest — computing visionary of all time. In the end, of course, the truth must lie somewhere in the middle. Sculley’s strengths tended to be Jobs’s weaknesses, and vice versa. Apple would have been far better off had the two been able to find a way to continue to work together. But, in Jobs’s case especially, that would have required a fundamental shift in who these men were.

The loss among Apple’s management of that old Jobsian spirit of zealotry, overblown and impractical though it could sometimes be, was felt keenly by the Macintosh even during these years of considerable success. Only Jean-Louis Gassée was around to try to provide a splash of the old spirit of iconoclastic idealism, and everyone had to agree in the end that he made a rather second-rate Steve Jobs. When Sculley tried on the mantle of visionary — as when he named his fluffy corporate autobiography Odyssey and subtitled it “a journey of adventure, ideas, and the future” — it never quite seemed to fit him right. The diction was always off somehow, like he was playing a Silicon Valley version of Mad Libs. “This is an adventure of passion and romance, not just progress and profit,” he told the January 1988 Macworld attendees, apparently feeling able to wax a little more poetic than usual before this audience of true believers. “Together we set a course for the world which promises to elevate the self-esteem of the individual rather than a future of subservience to impersonal institutions.” (Apple detractors might note that elevating their notoriously smug users’ self-esteem did indeed sometimes seem to be what the company was best at.)

It was hard not to feel that the Mac had lost something. Jobs had lured Sculley from Pepsi because the latter was widely regarded as a genius of consumer marketing; the Pepsi Challenge, one of the most iconic campaigns in the long history of the cola wars, had been his brainchild. And yet, even before Jobs’s acrimonious departure, Sculley, bowing to pressure from Apple’s stockholders, had oriented the Macintosh almost entirely toward taking on the faceless legions of IBM and Compaq that dominated business computing. Consumer computing was largely left to take care of itself in the form of the 8-bit Apple II line, whose final model, the technically impressive but hugely overpriced IIGS, languished with virtually no promotion. Sculley, a little out of his depth in Silicon Valley, was just following the conventional wisdom that business computing was where the real money was. Businesspeople tended to be turned off by wild-eyed talk of changing the world; thus Apple’s new, more sober facade. And they were equally turned off by any whiff of fun or, God forbid, games; thus the old sense of whimsy that had been one of the original Mac’s most charming attributes seemed to leach away a little more with each successive model.

Those who pointed out that business computing had a net worth many times that of home computing weren’t wrong, but they were missing something important and at least in retrospect fairly obvious: namely, the fact that most of the companies who could make good use of computers had already bought them by now. The business-computing industry would doubtless continue to be profitable for many and even to grow steadily alongside the economy, but its days of untapped potential and explosive growth were behind it. Consumer computing, on the other hand, was still largely virgin territory. Millions of people were out there who had been frustrated by the limitations of the machines at the heart of the brief-lived first home-computer boom, but who were still willing to be intrigued by the next generation of computing technology, still willing to be sold on computers as an everyday lifestyle accessory. Give them a truly elegant, easy-to-use computer — like, say, the Macintosh — and who knew what might happen. This was the vision Jef Raskin had had in starting the ball rolling on the Mac back in 1979, the one that had still been present, if somewhat obscured even then by a high price, in the first released version of the machine with its “the computer for the rest of us” tagline. And this was the vision that Sculley betrayed after Jobs’s departure by keeping prices sky-high and ignoring the consumer market.

“We don’t want to castrate our computers to make them inexpensive,” said Jean-Louis Gassée. “We make Hondas, we don’t make Yugos.” Fair enough, but the Mac was priced closer to Mercedes than Honda territory. And it was common knowledge that Apple’s profit margins remained just about the fattest in the industry, thus raising the question of how much “castration” would really be necessary to make a more reasonably priced Mac. The situation reached almost surrealistic levels with the release of the Mac IIfx in March of 1990, an admittedly “wicked fast” addition to the product line but one that cost $9870 sans monitor or video card, thus replacing the metaphorical with the literal in Gassée’s favored comparison: a complete Mac IIfx system cost more than most actual brand-new Hondas. By now, the idea of the Mac as “the computer for the rest of us” seemed a bitter joke.

Apple was choosing to fight over scraps of the business market when an untapped land of milk and honey — the land of consumer computing — lay just over the horizon. Instead of the Macintosh, the IBM-compatible machines lurched over in fits and starts to fill that space, adopting in the process most of the Mac’s best ideas, even if they seldom managed to implement those ideas quite as elegantly. By the time Apple woke up to what was happening in the 1990s and rushed to fill the gap with a welter of more reasonably priced consumer-grade Macs, it was too late. Computing as most Americans knew it was exclusively a Wintel world, Macs incompatible, artsy-fartsy oddballs. All but locked out of the fastest-growing sectors of personal computing, the very sectors the Macintosh had been so perfectly poised to absolutely own, Apple was destined to have a very difficult 1990s. So difficult, in fact, that they would survive the decade’s many lows only by the skin of their teeth.

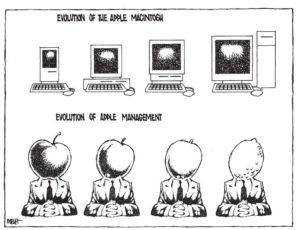

This cartoon by Tom Meyer, published in the San Francisco Chronicle, shows the emerging new popular consensus about Apple by the early 1990s: increasingly overpriced, bloated designs and increasingly clueless management.

Now that the 68000 Wars have faded into history and passions have cooled, we can see that the Macintosh was in some ways almost as ill-served by its parent company as was the Commodore Amiga by its. Apple’s management in the post-Jobs era, like Commodore’s, seemed in some fundamental way not to get the very creation they’d unleashed on the world. And so, as with the Amiga, it was left to the users of the Macintosh to take up the slack, to keep the vision thing in the equation. Thankfully, they did a heck of a job with that. Something in the Mac’s DNA, something which Apple’s new sobriety could mask but never destroy, led it to remain a hotbed of inspiring innovations that had little to do with the nuts and bolts of running a day-to-day business. Sometimes seemingly in spite of Apple’s best efforts, the most committed Mac loyalists never forgot the Jobsian rhetoric that had greeted the platform’s introduction, continuing to see it as something far more compelling and beautiful than a tool for business. A 1988 survey by Macworld magazine revealed that 85 percent of their readers, the true Mac hardcore, kept their Macs at home, where they used them at least some of the time for pleasure rather than business.

So, the Mac world remained the first place to look if you wanted to see what the artists and the dreamers were getting up to with computers. We’ve already seen some examples of their work in earlier articles. In the course of the next few, we’ll see some more.

(Sources: Amazing Computing of February 1988, April 1988, May 1988, and August 1988; Info of July/August 1988; Byte of May 1986, June 1986, November 1986, April 1987, October 1987, and June 1990; InfoWorld of November 26 1984; Computer Chronicles television episodes entitled “The New Macs,” “Macintosh Business Software,” “Macworld Special 1988,” “Business Graphics Part 1,” “Macworld Boston 1988,” “Macworld San Francisco 1989,” and “Desktop Presentation Software Part 1”; the books West of Eden: The End of Innocence at Apple Computer by Frank Rose, Apple Confidential 2.0: The Definitive History of the World’s Most Colorful Computer Company by Owen W. Linzmayer, and Insanely Great: The Life and Times of Macintosh, the Computer that Changed Everything by Steven Levy; Andy Hertzfeld’s website Folklore.)

Ken Brubaker

September 16, 2016 at 6:57 pm

There were actually 7 slots in the Apple II, not 6, with slot 7 having a few extra signals for video processing or something like that.

Jerry

September 17, 2016 at 3:44 am

The Apple II and II+ had 8 slots, numbered 0 through 7. The Apple IIe and IIgs had only 7 compatible slots, 1 through 7. The IIe had an auxiliary slot and the IIgs had a memory-expansion slot, however.

Jimmy Maher

September 17, 2016 at 7:46 am

I vacillated a bit between six and seven slots because of that video slot. I wasn’t sure if it was quite like the rest. But I changed it to seven now. Thanks!

David Cornelson

September 16, 2016 at 7:54 pm

I was at a publishing company in Milwaukee in 1985 when the IT director invited everyone to come into the board room. Sitting at the end of a 20′ table was the first Macintosh. Everyone had fun with the “mouse” and it turned into a small cocktail party.

Afterwards, it landed on my desk where I started playing with it and just out of the blue thought of digitizing some of our standard artwork. That was a huge enlightenment for the IT director and over the years they adopted Macs for all of their markup.

My sister still works there. On Macs.

Lisa H.

September 16, 2016 at 8:37 pm

For one thing, the pace of hardware and software development alike has slowed enough that a new computer can be viable just as it was purchased for ten years or more.

Ten years? Define “viable”.

I do have a seven-year-old laptop, but I doubt I will still be using it in another three years; it doesn’t run Windows 10 very well (despite Microsoft’s claims it is less resource-intensive than Windows 7) and getting a replacement battery or power supply has become a crapshoot since the manufacturer has moved on. My ancient Samsung flip-phone that is probably the oldest model Verizon will tolerate is viable in the sense that it can make and receive calls and plain text messages, but that’s about it (don’t bother trying to load a webpage on it!).

But at least I still use those things. If we will speak of Apple, then the iPad my husband won in a raffle in 2010 is viable in the sense that it will turn on, talk to the network, and run whatever is already installed on it. But since it cannot be upgraded past iOS 5, it’s been left in the dust, and even from the beginning it was kind of a pain even to read the web because its relatively small amount of RAM meant a lot of browser crashes. For practical purposes I don’t consider it viable anymore (and it was immediately displaced by the Kindle I got this past Christmas – I don’t think I’ve turned the iPad on since).

2 cents, YMMV, etc., etc.

even threatened users with electrocution should they persist in trying to open it.

I suppose if you manged to damage the inbuilt CRT…?

thanks to the revolutionary combination of Aldus PageMaker […] and an Apple LaserWriter printer

My high school newspaper’s setup, natch (although we did manual pasteup for the full size sheets).

the Mac IIx in March of 1990, an admittedly “wicked fast” addition to the product line but one that cost $9870 sans monitor or video card, thus replacing the metaphorical with the literal in Gassée’s favored comparison: a complete Mac IIx system

I think we had one of these in that newsroom. Wow.

I was about to make a general remark about how 1. I was there in the mid-90s so maybe it hadn’t been purchased for quite that price and 2. both the Steves went to that same high school and maybe that had something to do with it, but apparently Steve Wozniak made a gift in 1986 (see near the end of that section). I guess maybe they (we) had money still hanging around to buy a Mac IIx.

Joachim

September 16, 2016 at 10:26 pm

I do suspect your seven year old computer would have been more viable today if it was a desktop computer. That was what the Mac was, and for the most part I would agree with Jimmy Maher that a ten year old desktop would be viable today (if it was a decent setup in the first place, and have not been used by the kind of person who ends up with viruses all the time). And it wouldn’t have any of the typical laptop battery issues, either.

Darius Bacon

September 16, 2016 at 11:01 pm

I still use a 2007 MacBook Pro for some things. I’ll probably pass it on next year, but it runs modern Mac software and it’s not dramatically slower than my 2012 ThinkPad, which in turn is still in the same league as new machines. A 4-year-old computer was super outdated in the 80s and 90s.

Jimmy Maher

September 17, 2016 at 6:44 am

I was thinking more of desktop systems when I made that comparison. I think a desktop purchased in 2006 would still be perfectly viable today as the proverbial “grandparents’ computer”: i.e., fine for browsing the web, doing email, writing the occasional document with Microsoft Office, etc.

The mobile world is more in flux, and thus closer to the situation of the 1980s, but I think even it shows signs of settling down. Many have blamed the slowing pace of really noticeable technical advancement for slowing sales of the iPhone. While some people will always want the latest and greatest, for many the improvements in the newest models just don’t justify upgrading. So, while few mobile devices purchased in 2006 are viable today, that may be much less true in 2026 of mobile devices purchased today. We shall see. Personally, I’m still quite happy with an iPad 2 from 2011 — although I literally never use it for anything other than playing music, so that may have something to do with it — and a Kindle PaperWhite from 2012. My phone is a new(ish) Samsung something or other (a fairly cheap-o model), which I bought under duress because my creaky old Samsung S2 from God knows when was dying. But then, I’m pretty much in the grumpy-old-man “a phone is just a phone to me” camp when it comes to mobiles. With my laptop, where I need to be able to do Real Work, I’m much more demanding. I absolutely love the Dell XPS 13 I bought last year, but I doubt I’ll keep it for too many years because of the battery issue if nothing else.

Lisa H.

September 17, 2016 at 8:42 pm

I was thinking more of desktop systems when I made that comparison.

If you say so, but the preceding sentence did say “phones, tablets, laptops, or increasingly even desktop computers” – i.e., it sounds like the first three are the real examples under consideration.

Gnoman

September 18, 2016 at 12:22 am

Far more questionable is the assertion that a “walled garden” exists in any major form in the desktop world. Counting all variants and versions as one OS for simplicity (All Windows versions are Windows, all Linux distros are Linux, etc), the most popular desktop OS is Windows, where Microsoft periodically tries to put a walled garden of some sort in (dismally failing each time) but you can still install any software that’s compatible with the system, and a significant (and increasing) portion of the market is FOSS.

The second most popular OS, Linux, is derived from a philosophy that walled gardens are morally reprehensible. You won’t find much support for one there.

The closest thing to a successful walled garden at the software level in the desktop market is Steam, which is just one (albeit a massively popular one) of many distribution channels.

On a hardware level, the massive variety of hardware configurations that exist today is no less, and very probably greater, than it was during the rise of the Mac. The main difference is that the rise of abstraction layers mean that it largely doesn’t matter precisely what hardware you have, as long as it meets minimum standards.

Jimmy Maher

September 18, 2016 at 7:10 am

Yes, but where is it asserted that a walled garden exists in the desktop-computing world?

Jimmy Maher

September 18, 2016 at 7:07 am

Well, that paragraph is discussing reasons for the modern “black-box phenomenon” holistically. As of 2016 those reasons are probably more a case of the factor we’ve been discussing in these comments — the slowing pace of hardware development — in the case of desktop and perhaps some laptop computers, and the other I mentioned — the relative inexpensiveness that makes it feel reasonable for many people to throw devices away after two or three years — in the case of most mobile devices. But, I do think we can expect to see even the mobile world settle into much longer product cycles in the coming years, barring another major, disruptive breakthrough like the iPhone and iPad (and arguably the Kindle).

Gnoman

September 19, 2016 at 1:30 am

” Jobs was prescient in his determination to stamp out that chaos …The norm in personal computing as most people know it … even desktop computers — has long since become sealed boxes of one stripe or another. ”

How is it possible to take this as anything but saying that the desktop computer is becoming a “walled garden”? Maybe you didn’t mean to include a software walled garden of the sort that phones have, but on the hardware side you all-but-state that we have become the “Take your shit sandwich and be happy for it” market that Jobs envisioned all those years ago.

Desktops are largely immune to the “black box” phenomena, judging by the fact that prebuilt systems make up a very small portion of the desktop market and a far smaller portion of the personal (the vast majority of prebuilds are bought in bulk by companies) desktop market. Outside of businesses, the only people that buy prebuilds are those who don’t know any better or just want a basic internet device (a market that is plummeting to extinction in the face of the smartphone and tablet) on one hand or those that find it more economical to use one as a base for upgrading (which could hardly be considered to be a case of a “black box”) on the other.

A much bigger part of the market is in the “buy everything individual to get your system” as well as the “drop in a new video card and some RAM and you’ll be good for another three or four years” category – proving Wozniak and Gassée to be one hundred percent correct and consigning the vision of Jobs and Rankin to the ash heap of history.

Jimmy Maher

September 19, 2016 at 5:30 am

It seems we may have our terms a little confused. The term “walled garden” as I’ve always heard it used, and as I use it here, applies strictly to software, referring to a curated software ecosystem under the control of a corporate entity. I believe it dates back to The Cathedral & The Bazaar by Eric Raymond, if you’d like to get a sense of the original usage and the argument from which it sprang.

If we do wish to discuss hardware: I would suggest first of all that the adverb “increasingly,” which you snipped, might have been better left in — i.e., this is a trend that I see, not a reached destination. But in my experience, very, very few people are still buying a case and a motherboard and all the rest and putting a computer together. I am, other hacker types are — and I assume we’ll continue to do so as long as it’s practical. But everyone else I know goes to a department store and just buys a finished computer, then usually never opens it even if opening it is possible. And increasingly ;) often it’s not possible: I’m seeing a lot more desktop models on the shelves as sealed as any tablet, sometimes for instance with the computer and monitor built into one slim case. And of course, as you say, many more people are electing not to buy desktops at all in favor of sealed mobile boxes of one stripe or another.

Ian

September 17, 2016 at 1:14 pm

I’m still running a laptop from 2006, a IBM Thinkpad Z61p with a Core2 Duo T7600, 3GB RAM, 500GB SSD, ATi FireGL v5200 256MB with 1920 x 1200 15.4″ display, and a fingerprint scanner (Apple bought the rights to use this on their iPhone 5 I believe, although possibly just the software. I need to double check). It has USB 3.0 added in the ExpressCard/54 port. It can drive four screens with the right docking station, and that can even host a more recent desktop graphics card.

All this runs Windows 7 with absolute ease and it may even run 10 to a reasonable degree. Granted I do not do gaming on it, but apart from that it runs most uptodate software really well. I’m in no hurry to stop using this laptop, even though I have a more powerful desktop computer. However it all depends on what laptop brand and model you have, because there are other laptops in our family that are cheap Acer models, which on paper look the equal of the IBM Thinkpad, but in reality they cannot touch the performance and reliablility of the Thinkpad.

_RGTech

March 29, 2025 at 6:32 pm

Nearly 10 years later… I guess we can safely say that there are sometimes big generational leaps. If you’re lucky, you can get a device that lasts a decade or more… otherwise you may end up with a door stop in less than half of the time. And also, if you’re an early adopter, you buy into the fast-changing world where the dust hasn’t settled; so you have the same feeling as those 128k-Mac users back then.

Let’s say you always bought a new machine _exactly in the right time_ (and not the cheapest one then!) – for example in around 1992 (486, Win 3.1), 1996 (Pentium, Win95 B), 2002 (here you’d have to rely on an Athlon, not a Pentium-4-room heater; Windows XP), 2010 (Dual Core, Windows 7), 2020 or even 2025 (Multi Core, Windows 11), … you really got a lot of life out of your machines. (And even with the Windows 10 EOL on the horizon, we still refresh laptops with 1st-Generation Core CPUs using Linux, for people that can’t afford a new one! As long as a fullscreen Youtube HD video plays without a hitch…)

Granted, you might need room for RAM expansion and a faster and/or bigger drive (especially SSDs), which extends the useful life and/or makes the initial purchase cheaper. (Mac users usually pay more initially, then upgrade later, if at all… Wintel is the other way; decide for yourself ;))

It’s just not easy to see those steps when they arise. Who would have thought in 2001 that XP (itself only a facelift of Windows 2000, just like Windows Me to 98 to 95…so we thought) lasted over 10 years?

As for the phones and tablets… well, even Android 6 can still run (and install!) Whatsapp. Some phones of that generation even have removable batteries. Sadly the cheap price point at sale time has limited many of them to mediocre CPUs and low RAM, which renders them unusable today, especially the first wave of tablets. Apple, which generally has longer-lasting hardware, is currently phasing out devices that didn’t get iOS 15 (~10 year old phones). That still is, at the same time, “old” and “not old”, considering there wasn’t much improvement other than more memory and a lot more camera functions.

Anyway, as progress has slowed down, so has the life cycle. It’s a far cry from the 80’s and 90’s.

Steve-O

September 16, 2016 at 10:50 pm

One small correction: “Macworld” is spelled with a lowercase “w” (in contrast to the legitimately camelCase “MacUser”). A minor thing, I know, but a definite pet peeve of my several friends who have worked there.

Steve-O

September 16, 2016 at 10:53 pm

And now, a correction to my correction: The Swedish version of Macworld is, indeed, spelled “MacWorld” for some reason. That’s the only one, though.

Jimmy Maher

September 17, 2016 at 6:53 am

Not at all. Thank you!

Keith Palmer

September 16, 2016 at 11:10 pm

I have to admit that when I first heard you were working on an “Apple in the late 1980s” post, I got to wondering how I’d react to it, given how easy it seems for hindsight to provide “pride goeth before a fall” interpretations… but once I’d read it, as with your previous Macintosh post I thought “yes, that seems pretty fair.” Perhaps the comment about Apple at that point having a blind spot for “consumer computing” seemed more insightful to me than the seemingly familiar “they shoulda cut their prices” (or “they shoulda licensed the OS,” although that may not turn up quite as often these days). It might have even felt like something I’d been musing towards myself. It’s oddly tempting to wonder if that resulted from the Apple IIc not having sold well, although I know that as late as 1988 Apple released the “IIc Plus”, if into the void of promotion I’ve noticed period Apple II enthusiasts grew increasingly vehement about…

At a certain point I decided I wanted to take in a source biased towards the first years of the Macintosh and started buying old Macworld magazines. I’m not rushing through them (at the moment I’m most of the way through 1988, noticing the “Apple could cut its prices” comments every so often), but I did take some note earlier on of how some people and companies were “hacking the hardware” of the early Macintoshes to fit in internal hard drives hooked directly to the processor and memory expanded above 512 KB in “pre-Plus” models. Steven Levy’s column in the January 1987 issue sort of summarizes those efforts (which were, I suppose, more expensive and tricky than using expansion slots…)

This is a very small note of correction, but the infamously expensive Macintosh introduced in 1990 was the IIfx; the IIx showed up in 1988.

Jimmy Maher

September 17, 2016 at 7:06 am

Correction made. Thanks!

I think it’s really hard to separate the idea of consumer computing from that of lower prices than those Apple was charging. I don’t think that Apple needed to cut their prices to, say, Commodore and Atari levels, nor that doing so would even have been desirable from a marketing standpoint. But I do think they could have done very well in the pricing niche they inhabit today: a little more expensive than the competition, thereby maintaining that legendary Apple mystique, but not totally out of reach for ordinary, non-computer-obsessed people. That was the niche occupied by the Apple II.

FilfreFan

September 16, 2016 at 11:57 pm

“… their notoriously smug users’ self-esteem…”

Through economic circumstances, I had entered the Commodore ecosystem and progressed from the Vic 20 to the C64 to the 512K (expanded) Amiga 1000. Peter, a roommate and colleague in the 1985 or 1986 timeframe, seemed inexplicably delighted with his Mac and it’s relatively small black & white monitor. Proud as a peacock, he called me over to show me his wonderfully intuitive MacPaint. I agreed that it seemed pretty nice for a black & white paint package. “Try it! Use it!” he implored. Sitting down, I was possessed by an imp and began to deliberately misunderstand the functions of various icons. For example, I may have tried to use the selection tool to draw a shape rather than select an area, then acted confused and a little chagrined when it wouldn’t work. I continued in this vein with several “intuitive” icons, to an extreme that I was sure he would “cotton” to my prank, but instead he lit a slow fuse that built and built with each misunderstanding, leading to a powerful anger with my idiotic inability to “grok” the most intuitive computer interface on the planet.

Probably his investment dwarfed mine, and perhaps this contributed to his almost touching, but also off-putting, need for validation that his choices were far superior to mine. I think history has confirmed his bias, but you know, for our own reasons and based upon our own circumstances, we had each made choices that were appropriate to us.

Although totally unflattering, I admit that just recounting the story at this late date still yields a completely unseemly and gleeful delight at how easily this “… notoriously smug users’ self-esteem…” was punctured and his worldview threatened by nothing more than simple feigned ignorance.

Aside from that one moment in time, I’ve often acknowledged that I would prefer a Mac, if only I could afford one.

Alexander Freeman

September 17, 2016 at 5:46 am

Having read about the Amiga 500 and the Mac I and II, it seems the former was superior in just about way every way, though. If I’d had my choice of computer back then and didn’t have to worry about it losing in the marketplace, it might have been a toss up between the Amiga or Atari ST or MAYBE the Commodore 128, but nothing would have been worthy of any serious consideration.

Jimmy Maher

September 17, 2016 at 7:26 am

I wouldn’t say that. MacOS was a far more polished experience than the Amiga Workbench, for one thing, and the general build quality of the machine was better. The overall impression a Mac created was one of elegant solidity; an Amiga could feel like a very rickety structure indeed in comparison. This sense of security offered by the Mac extended to the parent company. Whatever mistakes Apple made, you could feel pretty certain they were committed to supporting the Mac in the long term, and that they would *be* around in the long term for that matter. Who knew with Commodore?

The Mac II’s design was still perhaps a little too minimalist, a fact that Byte magazine chided Apple for in their review:

This meant that a $1500 Amiga 500 system could outperform a $10,000 Mac II system for some types of fast animation. But there is more to a computer’s life than fast animation, and, as usual, the question of whether a Mac or Amiga was better should always be followed with another question: “Better at what” or “What do you actually want to do with your computer?”

For instance, the original Macs’ high-resolution (by the standards of the time) black-and-white screen was far better for desktop publishing than a flickering Amiga monitor. And the Mac II’s static color display capabilities were on the whole far superior, making it a better choice (if you could afford it) for most types of static image-processing. If you wanted primarily to play games or do desktop video, your best choice was probably the Amiga — as it was if your hacker’s heart just fell in love with this unique and fascinating machine.

Keith Palmer

September 17, 2016 at 1:26 pm

There were some comments in the final issues of Creative Computing along the lines of “Commodore’s sophisticated Amiga and Jack Tramiel’s inexpensive Atari ST will threaten the Macintosh from two directions at once” (although not everyone was pleased by that thought; one columnist came up with a laundry list of improvements to be made before it was too late, including squeezing two floppy drives and a portrait-format full-page monitor into the compact case). One of the reasons I started buying Macworld magazines was to see what responses might have been made to that sentiment… although I’m afraid the only thing I seemed to pick up on was an editorial sort of shrugging “who really needs colour in a business environment? Colour printers aren’t good enough to reproduce it.” As you said, after a certain while the comparison just didn’t seem to come up any more (save in the occasional letter saying “I wish I could have afforded a Macintosh, but my Amiga 500 seems quite good anyway.”)

Alexander Freeman

September 17, 2016 at 4:55 pm

Oh, hmmm… I didn’t know about the flickering problem on Amigas’ monitors. Well, it seems although Macs’ monitors were better for some things, Macs were basically primitive but elegant compared to Amigas.

I do agree lousy marketing and lack of support were the downfalls for the Amiga and Atari ST, though, which is why I said IF I didn’t have to worry about them losing in the marketplace. For all its bungling, Apple always seemed more committed to success than Commodore and Atari in late ’80s. I couldn’t agree more with your analysis of Jobs and Sculley.

Maybe one thing Commodore and Atari could have done better was to introduce a high-quality color printer somewhat early to their computers so as to make some headway into business and publishing. I’m sure it would have been very expensive, but I’m sure there would have been businesses willing to pay the cost.

Jimmy Maher

September 17, 2016 at 6:29 pm

The smartest thing Commodore could possibly have done for the Amiga in my opinion would have been to push early and aggressively into CD-ROM. If ever there was a computer that was crying out to be paired with a CD-ROM drive, it was this one. As it was, they managed to look like me-too bandwagon jumpers when “multimedia computing” finally took off, despite the Amiga having been the first real multimedia computer. But we’ll get deeper into all that in future article(s). ;)

_RGTech

March 29, 2025 at 6:58 pm

Well, you always could connect something like the HP Deskjet 500C to your Amiga.

I know we did (A500+DJ500 made perfect sense).

The downfall of the Amiga in the business world was – even with better monitors – Commodore’s reputation for cheap, unreliable machines, “toys” so to say, and the marketing that didn’t know what to do with the machine. Not even a affordable color laser printer could have saved that. IBM and Apple just were more _serious_, and that was that.

Eric

September 17, 2016 at 5:20 am

When you talk about the $9900 Mac, you mean IIfx, not the 1988 Mac IIx.

Eric

September 17, 2016 at 2:53 pm

You missed the second IIx/IIfx reference.

Jimmy Maher

September 17, 2016 at 3:20 pm

Woops! Thanks!

Ben L

September 18, 2016 at 5:12 am

I have to say- these articles just get better and better. A fantastic read.

Veronica Connor

September 18, 2016 at 3:27 pm

The high voltage warning on the Mac actually had some merit. The anode on a CRT can pretty easily put a couple dozen kilovolts into you if you touch it in the wrong places. This charge can be stored for days after being shut off. The risk of permanent injury is fairly low, but like a tube television, it’s best not to go poking around if you don’t know what you’re doing. CRTs are not like radios or computers. They are actually a wee bit dangerous.

William Hern

September 18, 2016 at 7:54 pm

Great piece Jimmy – well up to your usual high standard.

Raskin’s concept for the Mac was indeed very different to that of Jobs’. You can get a sense of just how different it was by looking at the Canon Cat, the machine that Raskin created after he left Apple. Released in 1987, it featured a text-based interface, with no GUI windowing system or mouse. Superficially a word processor system, it was actually capable of doing much more (thanks to the FORTH programming environment sitting just beneath the service) but few users ever tapped into this power. It’s an intriguing system nonetheless.

One item of minor trivia: as well as expansion slots, Jobs and Raskin also shared a dislike for on/off switches. Jobs insisted that the Mac didn’t have an on/off switch and the Canon Cat only gained one because of Canon engineers who thought that the absence of one in Raskin’s specification was an error.

Jimmy Maher

September 19, 2016 at 6:00 am

Yes, power management was another (admittedly minor) area in which the Mac (and it seems the Canon Cat) were very ahead of their time. I was wasting time this weekend watching one of those “teens react” videos on YouTube; they were asking the kids to try to use Windows 95. The kids were all shocked at the “It’s now safe to turn off your computer” message after shutting down — shocked the computer couldn’t turn *itself* off.

But the Mac had had auto-power-off for quite some years by that point. I know the Mac II had it in 1987, not sure about earlier models offhand. I’d actually mentioned this in the article at one point, then cut it as one of those details that can kill readability. (Funny how many of those seem to turn up later in the comments. For instance, I also cut a few paragraphs of Amiga comparisons.)

AguyinaRPG

September 20, 2016 at 2:28 pm

I’ve enjoyed how you’ve gone about explaining Apple and the intersection of Woz, Jobs, and Scully as it relates to the idea of computer vision. The company almost represents a “Yes, but maybe…” attitude through its persistent dead-ends and backtracking. Woz’s spirit of Apple resulted in the Apple IIGS which was a failure, the Mac was Jobs’ short term success, and Sculley’s willingness to change flip-flopped him back and forth.

I don’t think any book has really portrayed this struggle eloquently because they’re usually too busy praising Jobs and looking at Apple in a much more modern perspective. You’re absolutely right to say that limiting expansion was an awful idea, though Apple was smart to not be too liberal about it. Becoming another IBM clone company would have killed them in the long run. While I don’t much like Apple’s approach to the computer (and games) market now, it’s allowed them to survive and thrive amid the homogenized computer architectures of the world.

Martin

October 28, 2016 at 1:04 am

As thing stood, then, they were effectively paying a….

things?

Jimmy Maher

October 28, 2016 at 8:34 am

Thanks!

cbmeeks

July 13, 2017 at 1:59 pm

First time I saw a Macintosh (B/W model…can’t remember if it was an SE or not) was in my high school English class. My teacher used it as a desktop publishing platform and I remember being amazed at how sharp the screen looked. Fonts looked like curved, smooth fonts instead of the blocky text I remember on my TV.

Shortly after that I saw one in a game store running a copy of Dark Castle. I was so impressed by it! Not realizing that Dark Castle is an awful game. lol

Then I managed to buy me an Amiga 500 and I forgot how great the Mac looked. Years later, I now own four B/W Macs and several Amiga’s.

Jason

September 16, 2018 at 9:04 pm

Jean-Louis Gassée has a blog at mondaynote.com. It’s the only blog apart from this one that I check weekly for updates, for whatever that’s worth.

I have never read Gassée’s book, and it’s interesting to read about his maneuvering against Steve Jobs because when you read anything Gassée says about Jobs today, he sounds like the world’s biggest fan. He also never sounds the least bit bitter that he came this close to having the chance to mold Apple 2.0 in his image.

Jonathan O

January 16, 2021 at 3:14 pm

In “who had heretofore been constipated by the frustrating limitations of the closed Macintosh architecture”, did you really mean to say constipated? Even as a joke it sounds a bit odd.

Jimmy Maher

January 17, 2021 at 10:22 am

No sure what I was going for there, but I agree that it was a… strange choice of words. Thanks!

Ben

December 10, 2023 at 11:34 pm

jealously -> jealousy

even that that -> even than that

ebulliant -> ebullient

hell of job -> hell of a job

Jimmy Maher

December 11, 2023 at 3:09 pm

Thanks!