The real impact that airplanes had on the course of World War I was very limited in contrast to the wars that were still to come. That press and public latched onto the exploits of the airmen so eagerly was largely down to the sheer ugliness of the war on the ground, which proved notably lacking in the martial glory and strategic derring-do everyone had anticipated when the armies had first marched off to battle.

After the initial German advance into France was finally halted in late 1914, the ground war devolved into a static slaughter the likes of which no one had ever imagined it could become, for the very good reason that the world had never seen anything like it. The situation was born of the fatal combination of weapons of mass destruction with primitive command-and-control systems that made it impossible to use them in the service of anything other than the most indiscriminate, random killing. Heavy artillery had a disconcerting tendency to wipe out friendly rather than enemy forces, while poison-gas attacks, one of the most truly horrifying technologies of warfare ever invented, consisted during World War I of nothing more than opening huge tanks of the stuff when the wind was blowing toward the enemy lines and hoping it didn’t shift direction for a few hours. “Strategy” on the Western Front devolved into one side or the other getting antsy from time to time and launching a massive frontal assault at one spot or another along the line, leading to the gruesome spectacle of soldiers with rifles climbing laboriously over barbed wire in the face of hundreds of machine guns, while the generals stood behind them hoping the enemy would run out of bullets before their side ran out of men. Occasionally, at the cost of thousands or tens of thousands of lives, the enemy lines might bend a little under the onslaught, but they never broke.

With no real strategic gains to which to point, the generals were left to justify each successive bloodbath by waving vaguely at the effect it might be having on the enemy’s morale, or, bringing things down to the final brutal arbiter, claiming to have just possibly managed to kill slightly more enemy than friendly soldiers. Here, for instance, is what the British General John Charteris had to say in 1916 to justify the otherwise inconclusive Battle of the Somme — a battle which began with the bloodiest single day in the history of British arms and wound up killing or maiming more than 1 million men in all.

There is deterioration in the morale of the German Army in this battle, although people at home will not recognize it. Surrenders are more ready than they were at the beginning. Though far from being demoralised as an army, the Germans are not nearly so formidable a fighting machine as they were at the beginning of the battle. Our New Army has shown itself to be as good as the German Army. The battle is over and we shall not know the actual effect it has had on the Germans for many a long day, but it has certainly done all, and more, than we hoped for when we began. It stopped the Verdun attack. It collected a great weight of the German Army opposite us, and then broke it. It prevented the Germans hammering Russia, and it has undoubtedly worn down the German resistance to a great extent.

The years of war still to come would beg to differ with almost every one of even these tepid assessments. In this new inflationary era of warfare, 1 million casualties bought very, very little.

In the face of all this ugliness, the air war alone seemed like the clean, noble sort of war the public had expected going into this thing. Not for nothing did the metaphors that were applied to it always reach back to the eras of knights or gladiators — to allegedly cleaner, nobler eras of warfare. “They are the knighthood of this war, without fear and without reproach,” enthused British Prime Minister David Lloyd-George about the aviators, “and they recall the legendary days of chivalry, not merely by the daring of their exploits, but by the nobility of their spirit.” (What, one has to ask, of the thousand acts of quieter heroism that occurred among ordinary soldiers every hour inside the trenches on both sides? Had they no “nobility of spirit?” Even in war, the hierarchies of class remained as strong as ever.) Journalists covering the front began to tally up official “victory counts” for the pilots, with 5 victories making any individual pilot an ace, and thus worthy of closer observation as an up-and-comer. The ultimate honor was to become the ace of aces, the pilot with more victories than any other. The latest tallies were printed in newspapers, to be eagerly perused over the home-front breakfast table the way that peacetime readers might turn to the horse-race results or the latest cricket scores. The most successful aces became veritable celebrities, complete with adoring fan bases. As Edward Mannock was transferring to the air corps, baby-faced Albert Ball, the first of the great British aces and to this day still the best remembered, was much in the news for his exploits. Not yet 21 years old, he presented the very picture of modest, chivalrous young British manhood. “I only scrap because it is my duty,” he said. “Nothing makes me feel more rotten than to see them go down, but you see it is either them or me, so I must do my best to make it a case of them.”

Albert Ball, who broke all the rules and got away with it for quite some time thanks to his sheer skill as both a pilot and a gunner. He preferred to attack from below rather than above, preferred to prowl alone rather than as part of a flight. Mannock would spend much time later in the war trying to disabuse would-be Albert Balls of their delusions of single-handed heroism.

Mannock would prove a very different sort of air fighter than the famously reckless Ball, who is known on at least one or two occasions to have thrown himself into battle alone against six German planes. Certainly Mannock didn’t enter into the Royal Air Corps with any particularly romantic notions about it, even if he did write in his diary upon his acceptance that he would “strive to become a scout pilot like Ball.” He was simply seeking a way to do some good — and to kill some Germans, which he defined as largely the same thing.

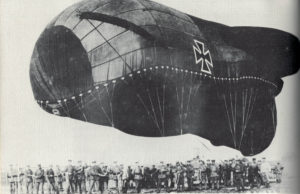

Although the war as a whole was half over by the time Mannock learned to fly, what would come to be regarded as the classic era of World War I dogfighting, subject of countless future books, movies, and games, was really just beginning. When the war had started in 1914, the air forces of the various combatants had consisted of no more than a few dozens or hundreds of rickety unarmed planes. Little thought had been given to the prospect of aerial combat; it was dangerous enough just trying to fly one of the things from Point A to Point B. The airplane was rather regarded as the ultimate reconnaissance tool, even better than the observation balloons armies had been using for years. United by the shared brotherhood of flight, the pilots for the opposing sides, who might very well know each other given how tiny the world of pre-war aviation had been, would blithely wave to one another when they happened to meet on their reconnaissance rounds and continue on their way. Only as casualties mounted and true hatred between the combatants began to set in did it begin to occur to pilots that it might be a good idea to prevent the aviators for the other side from returning home with a cockpit full of valuable information on the positioning of friendly forces. Thus many fliers took to carrying pistols or rifles up with them and taking potshots at enemy planes. Others started carrying up bags of bricks and chucking them at the enemy. But it’s doubtful whether any airplane ever managed to down another using such crude methods; nor were the heavy, slow, two-man observation craft themselves all that suited for aerial jousting. Clearly something better was needed if the war truly was to be taken into the sky. The era of the so-called “scout” plane — the name is a misnomer if ever there was one; its goal was not to “scout” anything but to shoot down enemy reconnaissance planes — was nigh.

Almost from the beginning, it had been clear that the ideal weapon of airborne war would be a machine gun mounted directly in front of the pilot, so that he could, to borrow the parlance of a later era, simply point his plane in an enemy’s direction and shoot. But the obvious problem with that was the propeller in the nose of the plane; it would be shot to splinters long before the pilot could hope to down an enemy. One possibility might be to mount the gun in the nose of a “pusher” aircraft — an aircraft in which, like in the original Wright brothers’ plane, the propeller “pushed” the airplane through the air from behind rather than “pulling” it along from in front. (Just such a design was the De Havilland DH.2, the only single-seater Mannock got a chance to fly before being posted to the front.) But the pusher configuration was inefficient and aerodynamically awkward, for which reasons it was already passing into aeronautical history; certainly it was hardly possible to build a fast and maneuverable would-be fighter plane using it. The best compromise anyone could come up with for a “tractor” aircraft — a plane with the propeller located in the nose of the fuselage — was to mount the machine gun above the pilot’s head, on the upper wing of a biplane. That way the bullets would fly over the propeller — but that way also meant that aerial gunnery became much more difficult, as the pilot had to reach over his head to fire a gun whose bullets would fly above his plane’s arc of flight.

In April of 1915, a French pilot named Roland Garros briefly terrorized the Western Front with a rather hair-raising solution to the problem of the nose-mounted machine gun in a tractor plane: he bolted heavy metal plates to the propeller blades of his little Morane monoplane, in the hope that they would deflect away those bullets that struck them. It worked, after a fashion, despite the ever-present danger of the force of the bullets’ impact eventually breaking the propeller, or of a bullet ricocheting into the engine, or for that matter into the pilot’s face — risks which do much to explain why no other Allied pilots proved willing to implement Garros’s scheme. Still, Garros managed to shoot down a few German planes with the setup before being forced down himself and taken prisoner. His captured plane was given to Anthony Fokker, a Dutch aeronautical engineer working for the Germans, with orders to come up with something similar. What he actually did come up with was something much, much better.

A Fokker Eindecker (“monoplane”) of the sort which, equipped with the first synchronizer gear, terrorized the Allies on the Western Front during the fall of 1915 despite being a mediocre performer in all respects other than gunnery.

Fokker devised a system of gears that would prevent the machine gun from firing during those instants when a propeller blade was directly in front of the muzzle. It was far from foolproof — especially during the early months, hapless pilots could and did occasionally shoot off their own propellers when the mechanism slipped a gear — but Fokker’s invention set the pattern that would hold true for all of the remaining years of the air war: that of a constant game of technological one-upsmanship. Introduced on the Western Front late in the summer of 1915, the synchronizer gear led to a period of absolute German dominance of the skies that Allied pilots came to call the “Fokker Scourge.”

In a telling measure of just how unexceptional the Fokker Eindecker really was, it was a two-man pusher, the Royal Aircraft Factory F.E. 2B, that ended the Fokker Scourge and briefly tipped the scales in favor of the Allies again even as they still struggled to perfect a reliable synchronizer gear of their own. Still, the F.E. 2B would be the last effective aircraft of its type. The future belonged to the “tractors.”

The tide of the air war ebbed and flowed throughout 1916, but by early 1917 the Allied forces were once again clearly getting the worst of it. Indeed, Mannock arrived just in time for the month destined to go down in infamy as “Bloody April.”

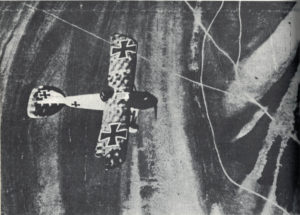

An Albatros D.III, the scourge of Bloody April, seen from above — the only angle from which any Allied pilot wanted to see one, if he had to see one at all.

It was a case of quality over quantity. To support the latest fruitless British offensive, near the village of Arras, France, the Royal Flying Corps could field 754 aircraft, 385 of them scouts. The Germans had just 264 airplanes on that section of the front, 114 of them scouts. But offsetting the three-to-one advantage the British enjoyed in sheer numbers was the technical superiority of the German planes and pilots. The latest German Albatros scouts were faster and tougher than anything the British could muster, and could climb much higher thanks to their high-compression engines — a critical advantage in air combat, where he who enjoys the advantage of height most often enjoys victory. Just as critically, they were armed with not one but two synchronized Spandau machine guns mounted on the cowl, capable of unleashing a devastating barrage of 1600 rounds per minute. The British, by contrast, had yet to perfect a foolproof synchronizer gear of their own. Their French-built Nieuport scouts — the plane the newly arrived Mannock would fly into battle — were equipped only with a single Lewis machine gun mounted above the wing. In addition to having to aim the thing in the middle of a dogfight without losing control of his airplane or being shot up by someone else — no mean feat in itself — the pilot had to constantly change out ammunition drums that held just 47 rounds each. This was the heyday of the German Jagdstaffeln (“hunting squadrons”), or “Jastas,” which ranged freely across the front at altitudes the Allied planes couldn’t dream of reaching. From their lofty perches, the German Albatroses could swoop down out of the sun and destroy their enemies before they even knew what was happening. The most feared of all the Jastas was Jasta 11, commanded by Manfred von Richthofen — the Red Baron, greatest ace of them all. He and his cohorts were always identifiable by the blood-red paint jobs their aircraft sported in arrogant defiance of the usual drab military color scheme.

The Red Baron (center) with some of his squadron mates. This picture was sold as a postcard in Germany, where Richthofen was celebrated as his era’s equivalent of a rock star.

The consequences for the men of the Royal Flying Corps were horrendous. As airmen were killed, they were replaced by sketchily trained greenhorns, often with less than 25 hours of total flying time, and with no real instruction whatsoever in the rapidly evolving wiles of airborne warfare. Little better than cannon fodder for the Jastas, after going down in flames they were replaced by still more hastily trained and activated new recruits. The vicious circle came fully to a head in Bloody April. That April of 1917, the British lost 275 aircraft, leading to the death of 207 men and the wounding of 214 more. Set against the carnage taking place in and around the trenches, these numbers may have been minuscule, but in relation to the relatively tiny numbers who took part in the war in the air they were staggering. One out of every three airplanes the British had on-hand at the beginning of April had been shot down by the end of the month; another airman was killed for every 92 hours of total flying time by British airplanes as a whole. April of 1917, Mannock’s baptism by fire, was the absolute most dangerous time of the entire war to be a British flyer.

Major-General Hugh Trenchard, the man in charge of Britain’s air war on the Western Front, had an inflexible strategy for dealing with the psychological fallout of casualties. It was best summed up by the oft-repeated maxim “no empty chairs at breakfast.” The fallen were not to be mourned or even acknowledged. Instead the possessions of a fallen airman were quickly whisked out of his room to make space for his replacement, who would likely arrive within hours from a pool of fresh faces waiting in the town of Saint-Omer, a staging area located just across the English Channel. Mannock spent just a few days there waiting for a spot to open up — i.e., waiting for someone to die, a wait that never took long — before being sent on April 6 to 40 Squadron, posted near the village of Bruay, west of the town of Lens.

Most soldiers who go to war have the comfort of doing so as a group, with the same people with whom they have trained and prepared for months. Not so Mannock and the other fledgling flyers arriving in France to plug the holes made by the relentless Albatros patrols. They went to war alone. The experience of one Second Lieutenant Geoffrey Hopkins, who somewhat unusually was posted directly from Britain to 22 Squadron, likely mirrors that of Mannock in most other respects.

I travelled by the ordinary leave train from Victoria to Dover and thence by ship to Boulogne, where we arrived about dark. Everybody else disembarking there seemed to know exactly what to do and where to go, but I had no idea whatsoever and stood by my camp kit and valise, feeling rather lost. Some kindly soul, who had perhaps had the same experience himself at an earlier date, asked me where I was going and, when I told him, advised me to report to the RTO (Railway Transport Officer). He laughed when I naively asked him what an RTO was! The RTO said, “Oh, yes, 22 Squadron, RFC. They’ll pick you up at Amiens railway station. You can catch a train early in the morning. The squadron is at a place called Bertangles.”

Next day an RFC corporal met me on the platform at Amiens station, took my kit to a Crossley tender outside, and drove me to a bar where, he said, I would find some other officers from the squadron. I found them there having a drink before returning to the aerodrome. I was introduced all round and we had a drink before setting off. We had a very crowded and noisy drive back. They belonged to C Flight and told me that I’d been posted to B Flight, where they dropped me at the mess, on a very cold night with thick snow on the ground. The first person I met on going into the mess was Gladstone, who had joined up with me from school. He introduced me to the others there, told me that the commanding officer and our flight commander were not there that night, and I should report in the morning. After something to eat and drink, I was shown my billet. This was a farmhouse in the village, my room being a sort of cubbyhole off the main living room with a bunk bed containing a pallisasse, filled with straw. I have no recollection of any bathing or sanitary arrangements — I don’t suppose there were any — but have vivid memories of how cold it was.

The veterans who made up the core of a squadron weren’t in the habit of being overly welcoming to the wide-eyed newcomers who were constantly washing up in their mess hall. It was a matter of emotional self-protection; the life expectancy of the average greenhorn at that time was measured in days rather than weeks or months, so there was little to be gained and much to be lost from forming bonds destined so quickly to be rent. If a pilot managed to stay alive for a few weeks, seemed to have a real knack for combat flying, then and only then would his relationship with his comrades deepen beyond the most cursory of formalities. It made for a cold reception indeed for many an already disoriented, uncertain young man.

For his part, Mannock had an unusually difficult time integrating into the life of 40 Squadron. For one thing, the man he was replacing was not another faceless, barely-remembered greenhorn, but rather a well-liked veteran who had finally met his match; Mannock’s presence in his bunk and in his chair at breakfast was a constant reminder of the old boon companion he was replacing. Mannock’s other problem was more typical of him. Determined as ever to assert himself and not to be cowed by his alleged betters, he overdid it, creating a very unfavorable first impression, as remembered by a fellow flier who betrays traces of the same old class snobbery that had dogged Mannock throughout his life:

His manner, speech, and familiarity were not liked. He seemed too cocky for his experience, which was nil. His arrival at the unit was not the best way to start. New men took their time and listened to the more experienced hands; Mannock was the complete opposite. He offered ideas about everything: how the war was going, how it should be fought, the role of scout pilots, what was wrong or right with our machines. Most men in his position, by that I mean a man from his background [emphasis mine] and with his lack of fighting experience, would have shut up and earned their place in the mess.

New fliers arrived at the front in a state of unpreparedness that must strike us today as extraordinary. With modern, combat-worthy aircraft virtually all earmarked to the front to replace the endless stream of losses, the airplanes the new arrivals had flown in training were wildly different from those they would be expected to fly into combat. Mannock had never before in his life flown a Nieuport 17, the nimble but rather under-powered and under-gunned French scout with which 40 Squadron was equipped. For that matter, he had flown a single-seat “tractor” aircraft of any sort for the first time only after arriving in France, when he was allowed a few practice flights in an obsolete Bristol Scout at Saint-Omer while waiting for his final posting. And trainees like Mannock had been given virtually no instruction in the vital discipline of aerial gunnery — a discipline whose mastery was made all the more vital by the awkward over-wing Lewis machine guns on the Nieuports that made every shot an exercise in deflection shooting.

The veterans of 40 Squadron may have been cool to newcomers, but a sense of fair play demanded that they at least give the fledglings a chance to put in a bit of practice flying and shooting in a Nieuport before being sent out over the front. Mannock was allowed about a week to do what he could to prepare himself. Gunnery practice involved laying a sheet of brightly-colored fabric of about six feet by six feet on the ground to serve as the target. Pilots would then dive toward it and take their shots, an exercise that would in theory force them to master the art of maintaining control of their aircraft while also manipulating the Lewis gun. It was damnably tricky. One William Bond, who arrived at 40 Squadron a few weeks before Mannock, later recalled being disappointed to learn after his first attempt that he’d managed to hit the target with just one shot out of 97. When he expressed his disappointment, the man in charge of the target range told him he had been the first in the last five days to hit the target at all.

Inevitably, some wiped out on the target range, wounding or killing themselves before they ever met an enemy airplane. Second Lieutenant Gordon Taylor of 66 Squadron describes an all too typical accident:

Pilots dived individually on a ground target near the aerodrome, firing their guns at the outline of a German aircraft laid out on the grass. I was watching a [Sopwith] Pup dive on this target only a day or two after we arrived. He was coming down steeply with engine on, firing, but holding his dive beyond the time when he should have started to pull out. I was in agony, trying to will him out of the dive before it was too late. He must have realised his mistake, seen the ground coming up, and pulled back too heavily on the stick. With a ridiculously harmless sound, like a child’s balloon bursting, the aeroplane disintegrated. The fuselage dived straight into the ground with the crunching noise of somebody treading on a matchbox. Tattered fragments of wing followed it, fluttering slowly to earth. The silence which settled over the scene was appalling.

Mannock’s career as a combat pilot very nearly ended before it began on the same tragic note. Pulling out of a dive at the end of a run, his right lower wing literally came off, pulling right out of the fuselage, the result of yet another problem that plagued the Allied pilots in their struggle against the Germans: the often terrible build quality of their airplanes, which were thrown together in haste in jerry-rigged factories to meet the constant demand for replacements. In what even his many detractors had to admit was a fine bit of flying, Mannock managed to bring his plane in upright for a crash landing that he escaped without injury. In his diary, he claimed that he was told he was the first pilot ever to manage such a feat.

On April 17, Mannock’s practice period, such as it was, was declared finished, and he made his first combat sortie over the front that evening. Herbert Ellis, another green pilot who had arrived at 40 Squadron at about the same time as Mannock, had turned heads that very morning by shooting down a German plane on his own first sortie. As William Bond later told the story, Ellis accomplished this feat largely by accident, after getting lost in the clouds and losing all contact with the other two planes that formed his flight: “He searched around for some time, not knowing at all where he was, and then suddenly a Hun two-seater came out of a cloud and flew at him. Ellis fired promptly and saw the Hun turn over, go down spinning, and crash to the ground.” Such were the fortunes of war. Mannock’s own debut would be far less auspicious.

No pilot ever forgot his first glimpse of the front, a sight of a devastation so complete as to be surreal, like flying above the surface of the moon. A pilot named Marcus Kaizer described (or perhaps failed to describe) it thus:

There was not a house left standing — just as if a big steamroller had passed over them. As we went further east, the shell holes in the ground grew more numerous until we reached the zone where each hole literally touches four or five others. I cannot describe the appearance of this to you — there were billions and all full of water. The whole looked like a wet sponge — hardly a tree or house visible.

As Mannock, flying in formation with five other Nieuports, was struggling to comprehend what he saw below, a German antiaircraft, or “Archie,” barrage began against them. Like so many other technologies of modern war, antiaircraft gunnery was in its infancy during the First World War, as gunners struggled to adapt to this strange new need to hit targets above them in the sky. Accuracy, at least when firing at planes at reasonably high altitude, was far from good, a fact that veteran pilots came to understand very well. In general, they simply ignored the Archie fire and continued on their way, trusting to the odds against the one-in-a-thousand lucky shellburst that might actually do them harm. For a newcomer like Mannock, however, all those bombs bursting in air around his airplane were profoundly unnerving. They caused him to commit the worst sin possible in the eyes of his peers: he panicked — “I did some stunts quite inadvertently” with “feelings very funny,” he wrote laconically in his diary that night — careening wildly out of formation in the hope of getting away from the barrage. When he regained his self-control, he found he had no idea where the rest of his patrol was. At last he blundered back to his aerodrome, alone in his ignominy. His comrades, who had already marked him for a blowhard in the officers’ mess, now began to see him as untrustworthy in the air as well — quite possibly a coward. That impression would only harden in the days to come.

The famous but indefinitely attributed description of war as “months of boredom punctuated by moments of extreme terror” dates from the First World War. In the case of fliers as well as their trench-bound counterparts, the months of boredom also encompassed enormous physical discomfort. It’s difficult indeed to overemphasize how taxing combat flying during World War I really was on the bodies of those who engaged in it. Mannock and his comrades typically patrolled the front at altitudes approaching 20,000 feet, right at the limit of what their Nieuports could manage, thereby to minimize one of the principal advantages enjoyed by the Germans: the fact that their aircraft could climb still higher. At that height, whether in winter or summer, the air was biting cold and terribly thin. A typical patrol began at dawn, the pilots emerging from the mess with as much protection from the cold as they could contrive. One Flight Lieutenant Robert Compston:

We were muffled up to the eyes and wore fleece-lined thigh boots drawn up over a fleece- or fur-lined Sidcot suit, a fur-lined helmet complete with chin guard and goggles with a strip of fur around them. Any parts of bare skin left open to the air were well-coated with whale oil to prevent frostbite. For our hands we found that an ordinary pair of silk gloves, if put on warm and then covered with the ordinary leather gauntlet gloves, retained enough heat for the whole patrol.

The dawn quiet of the aerodrome would ring out with the coughs and backfires of engines springing reluctantly to life. Flight Commander Colin Mackenzie:

All pilots should be in their machines five minutes before the time of starting, the engines having been previously tested by the petty officer of the flight. When all engines are ticking over and the petty officer signals to the leader that all the engines are running satisfactorily, the flight leader leaves the ground; the remaining four machines, if head to wind, should get off in thirty seconds, the order of getting off corresponding to each machine’s position in the formation.

Once all airborne, the flight would form up and set off for the front line, climbing all the while in the encroaching light of dawn into ever cooler and thinner air, straining for every bit of the precious altitude that could spell the difference between life and death. Compston:

While gaining height we saw away on our starboard beam a dark mass, which we knew to be the town of Arras, while the silvery, twisting thread straggling eastward showed us the River Scarpe. An occasional bursting shell and some Very lights betrayed the whereabouts of the lines, while a star shell threw into clear relief the chalky contour of the Hindenburg Line. Rudely we disturbed that quiet hour before the dawn.

This was flying at its most elemental, flying in a way that few modern pilots have ever known it. Up there in their rickety little open-cockpit aircraft, they felt like they could reach out a hand and touch the vault of heaven. If they could forget for a moment the grinding cold, the shortness of breath and pain in their heads and extremities brought about by oxygen deprivation, and the gnawing awareness that enemy aircraft could be lurking almost anywhere, they could appreciate the stunning beauty that surrounded them. Lieutenant George Kay:

These April clouds are perfectly clearly defined, and are like great mountains and castles of snow. You are sailing along in the sparkling sun under a clear blue sky and underneath is a fluffy white carpet.

Unfortunately, dwelling on the beauty of the scene was an excellent way to get yourself killed. Any one of those fluffy clouds could hide the Red Baron and his mates. The tension was unbearable, almost worse than the minute or two of chaos and terror that followed when the dreaded thing did finally happen, when German aircraft swept down out of the clouds or out of the sun. Lieutenant Cecil Lewis:

Our eyes were continually focusing, looking, craning our heads round, moving all the time looking for those black specks which would mean enemy aircraft at a great distance. Between clouds we would not be able to see the ground or only parts of it which would sort of slide into view like a magic-lantern screen far, far beneath. Clinging close together, about twenty or thirty yards between each machine, swaying, looking at our neighbors, setting ourselves just right so that we were all in position.

Contrary to myth and legend, extended dogfights, those much-vaunted extended aerial duels between these knights of the air, were quite rare. Mostly death came swiftly and unannounced; many a casualty of the war in the air literally never knew what hit him. The emotional toll of this life of overarching, eminently justified paranoia was staggering, while the physical toll it took was almost equally enormous. Spending several hours each day in a condition of oxygen deprivation brought on constant headaches and constant fatigue. Mannock wrote home to Jim Eyles that “I always feel tired and sleepy, and I can lie down and sleep anywhere at any time.” The oil and unburned fuel thrown off by the engine got into the skin and hair and was almost impossible to scrub out, while the quantities of the same noxious stuff which every pilot inadvertently inhaled led to persistent stomach cramps and diarrhea.

High-strung by temperament, Mannock didn’t cope very well with the strain — not ever really, and certainly not in his first weeks at the front. “Now I can understand,” he wrote in his diary, “what a tremendous strain to the nervous system active service flying is.” Unlike the majority of his peers, he survived as his first days turned into his first weeks at the front. But he didn’t acquit himself with any particular glory in so doing; while it’s true that he managed not to get shot down, it’s also true that he didn’t come close to shooting down anyone from the other side. Many of his comrades grew more than ever to see him, rightly or wrongly, as a shirker, the sort of flier who by some happenstance always seemed to be elsewhere when the going got really tough. When he turned for home early once or twice from particularly dangerous patrols due to what he claimed to be engine problems, it was viewed with great suspicion. George Lloyd, a fellow flier who arrived at 40 Squadron very shortly after Mannock:

Mannock was not actually called yellow, but many secret murmurings of an unsavoury nature reached my ears. I was told that he had shot down one single Hun out of control [Mannock was never officially credited with even this kill], and that he showed signs of being over-careful during engagements. He was further accused of being continually in the air practising gunnery, as a pretence of keenness. In other words, the innuendo was that he was suffering from cold feet.

Skeptical of the motivation behind it though Lloyd is, his comment about Mannock’s habit of constant gunnery practice points I think to something important. Even as he undoubtedly struggled to master his very real terror, Mannock was also at some level studying the nature of air combat, looking for ways to get better at it. It was perhaps every bit as much for this reason as any other that he seemed to hold himself apart from the fray; he was studying the field of battle before he threw himself into it. The polar opposite of a natural pilot and intuitive warrior like the famed Albert Ball, Mannock’s was, despite his relative lack of education, a very analytic mind. Nothing about fighting in the air seemed to come to him easily, but, once finally learned, lessons were never forgotten.

Take, for instance, this incident, which he wrote about in his diary on May 3:

Two mornings ago, C Flight escorted four Sopwiths on a photography stunt to Douai Aerodrome, Captain Keen, the new commander, leading. We were attacked from above over Douai. I tried my gun before going over the German lines, only to find that it was jammed, so I went over with a revolver only. A Hun in a beautiful yellow and green bus attacked me from behind. I wheeled round on him and howled like a dervish (although of course he couldn’t hear me), whereat he made off towards old Parry and attacked him, with me following, for the moral effect! Another one (a brown speckled one) attacked a Sopwith, and Keen blew the pilot to pieces and the Hun went spinning down from 12,000 feet to earth. Unfortunately, the Sopwith had been hit, and went down too, and there was I, a passenger, absolutely helpless, not having a gun, an easy prey for any of them, and they hadn’t the grit to close. Eventually they broke away, and then their Archie gunners got on the job and we had a hell of a time. At times, I wondered if I had a tailplane or not, they were so near. We came back over Arras with the three remaining Sopwiths, and excellent photos, and two vacant chairs at the Sopwith squadron mess! What is the good of it all?

Forced bravado aside (“they hadn’t the grit to close…”), a very shaken Mannock learned from this incident and one or two others like it to check his weapon personally before taking off. He would laboriously go over the gun itself and over each drum of ammunition, bullet by bullet, trusting no one else with the task out of the simple logic that no one else could possibly consider it as important as he, that no one else could possibly be guaranteed to do it as thoroughly as he would.

On May 7, Mannock and five companions attacked six German observation balloons hovering just above the front lines, a frenzied exercise that entailed screaming barely ten feet above the trenches at full throttle hoping not to be hit by the rifles and machine guns cannoning around them, then raking the balloons from below with their Lewis guns as they passed under them. Mannock managed to take one of them out in a blossom of flames before sprinting madly for home, his machine riddled with bullet holes and his nerves in an equally frazzled state. His was the only plane to make it back for a proper landing at the aerodrome. “I don’t want to go through such an experience again,” he wrote in his diary. The event marked his first kill in two senses. It was his first official tally as a pilot — and it was the first time he could definitively know that he had killed at least one other human being.

On the very same day, Albert Ball, who had now tallied 44 official victories, was shot down and killed, possibly by the Red Baron’s brother Lothar von Richthofen, whilst, as was his wont, prowling the front recklessly all alone. A torch had been passed, although it would be a long time before anyone realized it. Certainly anyone who had told Mannock’s squadron mates that the unstable, untrustworthy, uncouth big “Irishman” in their mess would someday replace the fallen hero Ball as Britain’s leading ace would have been roundly jeered. Mannock seemed anything but destined for glory. Just two days later on May 9, after another inconclusive engagement which raised the eyebrows of his squadron mates, he wrote in his diary how he had landed “with my knees shaking and my nerves all torn to bits. All my courage seems to have gone.” His commanding officer, showing more sympathy than would have most of Mannock’s other fellow fliers, took him briefly off active duty, judging him to be in no condition to fly at all, much less to fly and fight.

And yet, little by little, in a process that would require months yet to reach any sort of fruition, the worm was turning. Mannock the shirker was soon to become Mannock the reliable old hand, and waiting in the wings was Mannock the ace.

(Sources: The same as the first article in this series.)