After Richard Garriott and his colleagues at Origin Systems finished each Ultima game — after the manic final crunch of polishing and testing, after the release party, after the triumphant show appearances and interviews in full Lord British regalia — there must always arise the daunting question of what to do next. Garriott had set a higher standard for the series than that of any of its competitors almost from the very beginning, when he’d publicly declared that no Ultima would ever reuse the engine of its predecessor, that each new entry in the series would represent a significant technological leap over what had come before. And just to add to that pressure, starting with Ultima IV he’d begun challenging himself to make each new Ultima a major thematic statement that also built on what had come before. Both of these bars became harder and harder to meet as the series advanced.

As if that didn’t present enough of a burden, each individual entry in the series came with its own unique psychological hurdles for Garriott to overcome. For example, by the time he started thinking about what Ultima V should be he’d reached the limits of what a single talented young man like himself could design, program, write, and draw all by himself on his trusty Apple II. It had taken him almost a year — a rather uncomfortable year for his brother Robert and the rest of Origin’s management — to accept that reality and to begin to work in earnest on Ultima V with a team of others.

The challenge Garriott faced after finishing and releasing that game in March of 1988 was in its way even more emotionally fraught: the challenge of accepting that, just as he’d reached the limits of what he could do alone on the Apple II a couple of years ago, he’d now reached the limits of what any number of people could do on Steve Wozniak’s humble little 8-bit creation. Ultima V still stands today as one of the most ambitious things anyone has ever done on an Apple II; it was hard at the time and remains hard today to imagine how Origin could possibly push the machine much further. Yet that wasn’t even the biggest problem associated with sticking with the platform; the biggest problem could be seen on each monthly sales report, which showed the Apple II’s numbers falling off even faster than those of the Commodore 64, the only other viable 8-bit computer remaining in the American market.

After serving as the main programmer on Ultima V, John Miles’s only major contribution to Ultima VI was the opening sequence. The creepy poster of a pole-dancing centaur hanging on the Avatar’s wall back on Earth has provoked much comment over the years…

Garriott was hardly alone at Origin in feeling hugely loyal to the Apple II, the only microcomputer he’d ever programmed. While most game developers in those days ported their titles to many platforms, almost all had one which they favored. Just as Epyx knew the Commodore 64 better than anyone else, Sierra had placed their bets on MS-DOS, and Cinemaware was all about the Commodore Amiga, Origin was an Apple II shop through and through. Of the eleven games they’d released from their founding in 1983 through to the end of 1988, all but one had been born and raised on an Apple II.

Reports vary on how long and hard Origin tried to make Ultima VI work on the Apple II. Richard Garriott, who does enjoy a dramatic story even more than most of us, has claimed that Origin wound up scrapping nine or even twelve full months of work; John Miles, who had done the bulk of the programming for Ultima V and was originally slated to fill the same role for the sequel, estimated to me that “we probably spent a few months on editors and other utilities before we came to our senses.” At any rate, by March of 1989, the one-year anniversary of Ultima V‘s release, the painful decision had been made to switch not only Ultima VI but all of Origin’s ongoing and future projects to MS-DOS, the platform that was shaping up as the irresistible force in American computer gaming. A slightly petulant but nevertheless resigned Richard Garriott slapped an Apple sticker over the logo of the anonymous PC clone now sitting on his desk and got with the program.

Richard Garriott with an orrery, one of the many toys he kept at the recently purchased Austin house he called Britannia Manor.

Origin was in a very awkward spot. Having frittered away a full year recovering from the strain of making the previous Ultima, trying to decide what the next Ultima should be, and traveling down the technological cul de sac that was now the Apple II, they simply had to have Ultima VI finished — meaning designed and coded from nothing on an entirely new platform — within one more year if the company was to survive. Origin had never had more than a modestly successful game that wasn’t an Ultima; the only way their business model worked was if Richard Garriott every couple of years delivered a groundbreaking new entry in their one and only popular franchise and it sold 200,000 copies or more.

John Miles, lacking a strong background in MS-DOS programming and the C language in which all future Ultimas would be coded, was transferred off the team to get himself up to speed and, soon enough, to work on middleware libraries and tools for the company’s other programmers. Replacing him on the project in Origin’s new offices in Austin, Texas, were Herman Miller and Cheryl Chen, a pair of refugees from the old offices in New Hampshire, which had finally been shuttered completely in January of 1989. It was a big step for both of them to go from coding what until quite recently had been afterthought MS-DOS versions of Origin’s games to taking a place at the center of the most critical project in the company. Fortunately, both would prove more than up to the task.

Just as Garriott had quickly learned to like the efficiency of not being personally responsible for implementing every single aspect of Ultima V, he soon found plenty to like about the switch to MS-DOS. The new platform had four times the memory of the Apple II machines Origin had been targeting before, along with (comparatively) blazing-fast processors, hard drives, 256-color VGA graphics, sound cards, and mice. A series that had been threatening to burst the seams of the Apple II now had room to roam again. For the first time with Ultima VI, time rather than technology was the primary restraint on Garriott’s ambitions.

But arguably the real savior of Ultima VI was not a new computing platform but a new Origin employee: one Warren Spector, who would go on to join Garriott and Chris Roberts — much more on him in a future article — as one of the three world-famous game designers to come out of the little collective known as Origin Systems. Born in 1955 in New York City, Spector had originally imagined for himself a life in academia as a film scholar. After earning his Master’s from the University of Texas in 1980, he’d spent the next few years working toward his PhD and teaching undergraduate classes. But he had also discovered tabletop gaming at university, from Avalon Hill war games to Dungeons & Dragons. When a job as a research archivist which he’d thought would be his ticket to the academic big leagues unexpectedly ended after just a few months, he wound up as an editor and eventually a full-fledged game designer at Steve Jackson Games, maker of card games, board games, and RPGs, and a mainstay of Austin gaming circles. It was through Steve Jackson, like Richard Garriott a dedicated member of Austin’s local branch of the Society for Creative Anachronism, that Spector first became friendly with the gang at Origin; he also discovered Ultima IV, a game that had a profound effect on him. He left Austin in March of 1987 for a sojourn in Wisconsin with TSR, the makers of Dungeons & Dragons, but, jonesing for the warm weather and good barbecue of the city that had become his adopted hometown, he applied for a job with Origin two years later. Whatever role his acquaintance with Richard Garriott and some of the other folks there played in getting him an interview, it certainly didn’t get him a job all by itself; Spector claims that Dallas Snell, Robert Garriott’s right-hand man running the business side of the operation, grilled him for an incredible nine hours before judging him worthy of employment. (“May you never have to live through something like this just to get a job,” he wishes for all and sundry.) Starting work at Origin on April 12, 1989, he was given the role of producer on Ultima VI, the high man on the project totem pole excepting only Richard Garriott himself.

Age 33 and married, Spector was one of the oldest people employed by this very young company; he realized to his shock shortly after his arrival that he had magazine subscriptions older than Origin’s up-and-coming star Chris Roberts. A certain wisdom born of his age, along with a certain cultural literacy born of all those years spent in university circles, would serve Origin well in the seven years he would remain there. Coming into a company full of young men who had grand dreams of, as their company’s tagline would have it, “creating worlds,” but whose cultural reference points didn’t usually reach much beyond Lord of the Rings and Star Wars, Spector was able to articulate Origin’s ambitions for interactive storytelling in a way that most of the others could not, and in time would use his growing influence to convince management of the need for a real, professional writing team to realize those ambitions. In the shorter term — i.e., in the term of the Ultima VI project — he served as some badly needed adult supervision, systematizing the process of development by providing everyone on his team with clear responsibilities and by providing the project as a whole with the when and what of clear milestone goals. The project was so far behind that everyone involved could look forward to almost a year of solid crunch time as it was; Spector figured there was no point in making things even harder by letting chaos reign.

On the Ultima V project, it had been Dallas Snell who had filled the role of producer, but Snell, while an adept organizer and administrator, wasn’t a game designer or a creative force by disposition. Spector, though, proved himself capable of tackling the Ultima VI project from both sides, hammering out concrete design documents from the sometimes abstracted musings of Richard Garriott, then coming up with clear plans to bring them to fruition. In the end, the role he would play in the creation of Ultima VI was as important as that of Garriott himself. Having learned to share the technical burden with Ultima V — or by now to pass it off entirely; he never learned C and would never write a single line of code for any commercial game ever again — Garriott was now learning to share the creative burden as well, another necessary trade-off if his ever greater ambitions for his games were to be realized.

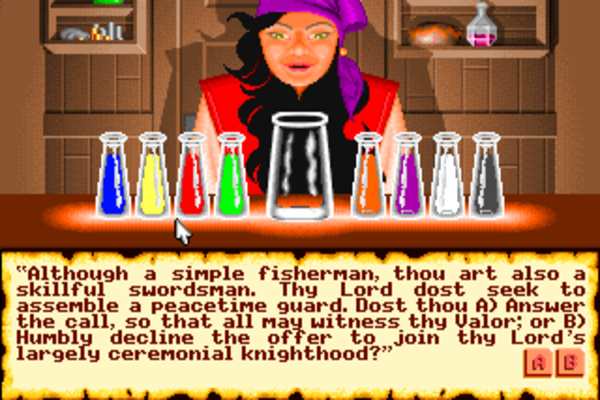

If you choose not to import an Ultima V character into Ultima VI, you go through the old Ultima IV personality test, complete with gypsy soothsayer, to come up with your personal version of the Avatar. By this time, however, with the series getting increasingly plot-heavy and the Avatar’s personality ever more fleshed-out within the games, the personality test was starting to feel a little pointless. Blogger Chet Bolingbroke, the “CRPG Addict,” cogently captured the problems inherent in insisting that all of these disparate Ultima games had the same hero:

Then there’s the Avatar. Not only is it unnecessary to make him the hero of the first three games, as if the Sosarians and Britannians are so inept they always need outside help to solve their problems, but I honestly think the series should have abandoned the concept after Ultima IV. In that game, it worked perfectly. The creators were making a meta-commentary on the very nature of playing role-playing games. The Avatar was clearly meant to be the player himself or herself, warped into the land through the “moongate” of his or her computer screen, represented as a literal avatar in the game window. Ultima IV was a game that invited the player to act in a way that was more courageous, more virtuous, more adventurous than in the real world. At the end of the game, when you’re manifestly returned to your real life, you’re invited to “live as an example to thine own people”–to apply the lesson of the seven virtues to the real world. It was brilliant. They should have left it alone.

Already in Ultima V, though, they were weakening the concept. In that game, the Avatar is clearly not you, but some guy who lives alone in his single-family house of a precise layout. But fine, you rationalize, all that is just a metaphor for where you actually do live. By Ultima VI, you have some weird picture of a pole-dancing centaur girl on your wall, you’re inescapably a white male with long brown hair.

Following what had always been Richard Garriott’s standard approach to making an Ultima, the Ultima VI team concentrated on building their technology and then building a world around it before adding a plot or otherwise trying to turn it all into a real game with a distinct goal. Garriott and others at Origin would always name Times of Lore, a Commodore 64 action/CRPG hybrid written by Chris Roberts and published by Origin in 1988, as the main influence on the new Ultima VI interface, the most radically overhauled version of same ever to appear in an Ultima title. That said, it should be noted that Times of Lore itself lifted many or most of its own innovations from The Faery Tale Adventure, David Joiner’s deeply flawed but beautiful and oddly compelling Commodore Amiga action/CRPG of 1987. By way of completing the chain, much of Times of Lore‘s interface was imported wholesale into Ultima VI; even many of the onscreen icons looked exactly the same. The entire game could now be controlled, if the player liked, with a mouse, with all of the keyed commands duplicated as onscreen buttons; this forced Origin to reduce the “alphabet soup” that had been previous Ultima interfaces, which by Ultima V had used every letter in the alphabet plus some additional key combinations, to ten buttons, with the generic “use” as the workhorse taking the place of a multitude of specifics.

Another influence, one which Origin was for obvious reasons less eager to publicly acknowledge than that of Times of Lore, was FTL’s landmark 1987 CRPG Dungeon Master, a game whose influence on its industry can hardly be overstated. John Miles remembers lots of people at Origin scrambling for time on the company’s single Atari ST in order to play it soon after its release. Garriott himself has acknowledged being “ecstatic” for his first few hours playing it at all the “neat new things I could do.” Origin co-opted Dungeon Master‘s graphical approach to inventory management, including the soon-to-be ubiquitous “paper doll” method of showing what characters were wearing and carrying.

Taking a cue from theories about good interface design dating back to Xerox PARC and Apple’s Macintosh design team, The Faery Tale Adventure, Times of Lore, and Dungeon Master had all abandoned “modes”: different interfaces — in a sense entirely different programs — which take over as the player navigates through the game. The Ultima series, like most 1980s CRPGs, had heretofore been full of these modes. There was one mode for wilderness travel; another for exploring cities, towns, and castles; another, switching from a third-person overhead view to a first-person view like Wizardry (or, for that matter, Dungeon Master), for dungeon delving. And when a fight began in any of these modes, the game switched to yet another mode for resolving the combat.

Ultima VI collapsed all of these modes down into a single unified experience. Wilderness, cities, and dungeons now all appeared on a single contiguous map on which combat also occurred, alongside everything else possible in the game; Ultima‘s traditionally first-person dungeons were now displayed using an overhead view like the rest of the game. From the standpoint of realism, this was a huge step back; speaking in strictly realistic terms, either the previously immense continent of Britannia must now be about the size of a small suburb or the Avatar and everyone else there must now be giants, building houses that sprawled over dozens of square miles. But, as we’ve had plenty of occasion to discuss in previous articles, the most realistic game design doesn’t always make the best game design. From the standpoint of creating an immersive, consistent experience for the player, the new interface was a huge step forward.

As the world of Britannia had grown more complex, the need to give the player a unified window into it had grown to match, in ways that were perhaps more obvious to the designers than they might have been to the players. The differences between the first-person view used for dungeon delving and the third-person view used for everything else had become a particular pain. Richard Garriott had this to say about the problems that were already dogging him when creating Ultima V, and the changes he thus chose to make in Ultima VI:

Everything that you can pick up and use [in Ultima V] has to be able to function in 3D [i.e., first person] and also in 2D [third person]. That meant I had to either restrict the set of things players can use to ones that I know I can make work in 3D or 2D, or make them sometimes work in 2D but not always work in 3D or vice versa, or they will do different things in one versus the other. None of those are consistent, and since I’m trying to create an holistic world, I got rid of the 3D dungeons.

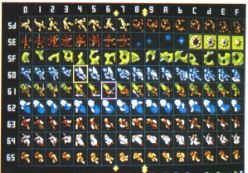

Ultima V had introduced the concept of a “living world” full of interactive everyday objects, along with characters who went about their business during the course of the day, living lives of their own. Ultima VI would build on that template. The world was still constructed, jigsaw-like, from piles of tile graphics, an approach dating all the way back to Ultima I. Whereas that game had offered 16 tiles, however, Ultima VI offered 2048, all or almost all of them drawn by Origin’s most stalwart artist, Denis Loubet, whose association with Richard Garriott stretched all the way back to drawing the box art for the California Pacific release of Akalabeth. Included among these building blocks were animated tiles of several frames — so that, for instance, a water wheel could actually spin inside a mill and flames in a fireplace could flicker. Dynamic, directional lighting of the whole scene was made possible by the 256 colors of VGA. While Ultima V had already had a day-to-night cycle, in Ultima VI the sun actually rose in the east and set in the west, and torches and other light sources cast a realistic glow onto their surroundings.

In a clear signal of where the series’s priorities now lay, other traditional aspects of CRPGs were scaled back, moving the series further from its roots in tabletop Dungeons & Dragons. Combat, having gotten as complicated and tactical as it ever would with Ultima V, was simplified, with a new “auto-combat” mode included for those who didn’t want to muck with it at all; the last vestiges of distinct character races and classes were removed; ability scores were boiled down to just three numbers for Strength, Dexterity, and Intelligence. The need to mix reagents in order to cast spells, one of the most mind-numbingly boring aspects of a series that had always made you do far too many boring things, was finally dispensed with; I can’t help but imagine legions of veteran Ultima players breathing a sigh of relief when they read in the manual that “the preparation of a spell’s reagents is performed at the moment of spellcasting.” The dodgy parser-based conversation system of the last couple of games, which had required you to try typing in every noun mentioned by your interlocutor on the off chance that it would elicit vital further information, was made vastly less painful by the simple expedient of highlighting in the text those subjects into which you could inquire further.

Inevitably, these changes didn’t always sit well with purists, then or now. Given the decreasing interest in statistics and combat evinced by the Ultima series as time went on, as well as the increasing emphasis on what we might call solving the puzzles of its ever more intricate worlds, some have accused later installments of the series of being gussied-up adventure games in CRPG clothing; “the last real Ultima was Ultima V” isn’t a hard sentiment to find from a vocal minority on the modern Internet. What gives the lie to that assertion is the depth of the world modeling, which makes these later Ultimas flexible in ways that adventure games aren’t. Everything found in the world has, at a minimum, a size, a weight, and a strength. Say, then, that you’re stymied by a locked door. There might be a set-piece solution for the problem in the form of a key you can find, steal, or trade for, but it’s probably also possible to beat the door down with a sufficiently big stick and a sufficiently strong character, or if all else fails to blast it open with a barrel of dynamite. Thus your problems can almost never become insurmountable, even if you screw up somewhere else. Very few other games from Ultima VI‘s day made any serious attempt to venture down this path. Infocom’s Beyond Zork tried, somewhat halfheartedly, and largely failed at it; Sierra’s Hero’s Quest was much more successful at it, but on nothing like the scale of an Ultima. Tellingly, almost all of the “alternate solutions” to Ultima VI‘s puzzles emerge organically from the simulation, with no designer input whatsoever. Richard Garriott:

I start by building a world which you can interact with as naturally as possible. As long as I have the world acting naturally, if I build a world that is prolific enough, that has as many different kinds of natural ways to act and react as possible, like the real world does, then I can design a scenario for which I know the end goal of the story. But exactly whether I have to use a key to unlock the door, or whether it’s an axe I pick up to chop down the door, is largely irrelevant.

The complexity of the world model was such that Ultima VI became the first installment that would let the player get a job to earn money in lieu of the standard CRPG approach of killing monsters and taking their loot. You can buy a sack of grain from a local farmer, take the grain to a mill and grind it into flour, then sell the flour to a baker — or sneak into his bakery at night to bake your own bread using his oven. Even by the standards of today, the living world inside Ultima VI is a remarkable achievement — not to mention a godsend to those of us bored with killing monsters; you can be very successful in Ultima VI whilst doing very little killing at all.

A rare glimpse of Origin’s in-house Ultima VI world editor, which looks surprisingly similar to the game itself.

Plot spoilers begin!

It wasn’t until October of 1989, just five months before the game absolutely, positively had to ship, that Richard Garriott turned his attention to the Avatar’s reason for being in Britannia this time around. The core idea behind the plot came to him during a night out on Austin’s Sixth Street: he decided he wanted to pitch the Avatar into a holy war against enemies who, in classically subversive Ultima fashion, turn out not to be evil at all. In two or three weeks spent locked together alone in a room, subsisting on takeout Chinese food, Richard Garriott and Warren Spector created the “game” part of Ultima VI from this seed, with Spector writing it all down in a soy-sauce-bespattered notebook. Here Spector proved himself more invaluable than ever. He could corral Garriott’s sometimes unruly thoughts into a coherent plan on the page, whilst offering plenty of contributions of his own. And he, almost uniquely among his peers at Origin, commanded enough of Garriott’s respect — was enough of a creative force in his own right — that he could rein in the bad and/or overambitious ideas that in previous Ultimas would have had to be attempted and proved impractical to their originator. Given the compressed development cycle, this contribution too was vital. Spector:

An insanely complicated process, plotting an Ultima. I’ve written a novel, I’ve written [tabletop] role-playing games, I’ve written board games, and I’ve never seen a process this complicated. The interactions among all the characters — there are hundreds of people in Britannia now, hundreds of them. Not only that, but there are hundreds of places and people that players expect to see because they appeared in five earlier Ultimas.

Everybody in the realm ended up being a crucial link in a chain that adds up to this immense, huge, wonderful, colossal world. It was a remarkably complicated process, and that notebook was the key to keeping it all under control.

The chain of information you follow in Ultima VI is, it must be said, far clearer than in any of the previous games. Solving this one must still be a matter of methodically talking to everyone and assembling a notebook full of clues — i.e., of essentially recreating Garriott and Spector’s design notebook — but there are no outrageous intuitive leaps required this time out, nor any vital clues hidden in outrageously out-of-the-way locations. For the first time since Ultima I, a reasonable person can reasonably be expected to solve this Ultima without turning it into a major life commitment. The difference is apparent literally from your first moments in the game: whereas Ultima V dumps you into a hut in the middle of the wilderness — you don’t even know where in the wilderness — with no direction whatsoever, Ultima VI starts you in Lord British’s castle, and your first conversation with him immediately provides you with your first leads to run down. From that point forward, you’ll never be at a total loss for what to do next as long as you do your due diligence in the form of careful note-taking. Again, I have to attribute much of this welcome new spirit of accessibility and solubility to the influence of Warren Spector.

Ultima VI pushes the “Gargoyles are evil!” angle hard early on, going so far as to have the seemingly demonic beasts nearly sacrifice you to whatever dark gods they worship. This of course only makes the big plot twist, when it arrives, all the more shocking.

At the beginning of Ultima VI, the Avatar — i.e., you — is called back to Britannia from his homeworld of Earth yet again by the remarkably inept monarch Lord British to deal with yet another crisis which threatens his land. Hordes of terrifyingly demonic-looking Gargoyles are pouring out of fissures which have opened up in the ground everywhere and making savage war upon the land. They’ve seized and desecrated the eight Shrines of Virtue, and are trying to get their hands on the Codex of Ultimate Wisdom, the greatest symbol of your achievements in Ultima IV.

But, in keeping with the shades of gray the series had begun to layer over the Virtues with Ultima V, nothing is quite as it seems. In the course of the game, you discover that the Gargoyles have good reason to hate and fear humans in general and you the Avatar in particular, even if those reasons are more reflective of carelessness and ignorance on the part of you and Lord British’s peoples than they are of malice. To make matters worse, the Gargoyles are acting upon a religious prophecy — conventional religion tends to take a beating in Ultima games — and have come to see the Avatar as nothing less than the Antichrist in their own version of the Book of Revelation. As your understanding of their plight grows, your goal shifts from that of ridding the land of the Gargoyle scourge by violent means to that of walking them back from attributing everything to a foreordained prophecy and coming to a peaceful accommodation with them.

Ultima VI‘s subtitle, chosen very late in the development process, is as subtly subversive as the rest of the plot. Not until very near the end of the game do you realize that The False Prophet is in fact you, the Avatar. As the old cliché says, there are two sides to every story. Sadly, the big plot twist was already spoiled by Richard Garriott in interviews before Ultima VI was even released, so vanishingly few players have ever gotten to experience its impact cold.

When discussing the story of Ultima VI, we shouldn’t ignore the real-world events that were showing up on the nightly news while Garriott and Spector were writing it. Mikhail Gorbachev had just made the impossibly brave decision to voluntarily dissolve the Soviet empire and let its vassal states go their own way, and just like that the Cold War had ended, not in the nuclear apocalypse so many had anticipated as its only possible end game but rather in the most blessed of all anticlimaxes in human history. For the first time in a generation, East was truly meeting West again, and each side was discovering that the other wasn’t nearly as demonic as they had been raised to believe. On November 10, 1989, just as Garriott and Spector were finishing their design notebook, an irresistible tide of mostly young people burst through Berlin’s forbidding Checkpoint Charlie to greet their counterparts on the other side, as befuddled guards, the last remnants of the old order, looked on and wondered what to do. It was a time of extraordinary change and hope, and the message of Ultima VI resonated with the strains of history.

Plot spoilers end.

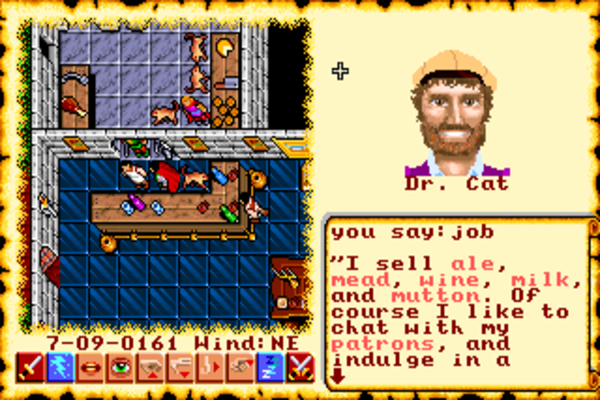

When Garriott and Spector emerged from their self-imposed quarantine, the first person to whom they gave their notebook was an eccentric character with strong furry tendencies who had been born as David Shapiro, but who was known to one and all at Origin as Dr. Cat. Dr. Cat had been friends with Richard Garriott for almost as long as Denis Loubet, having first worked at Origin for a while when it was still being run out of Richard’s parents’ garage in suburban Houston. A programmer by trade — he had done the Commodore 64 port of Ultima V — Dr. Cat was given the de facto role of head writer for Ultima VI, apparently because he wasn’t terribly busy with anything else at the time. Over the next several months, he wrote most of the dialog for most of the many characters the Avatar would need to speak with in order to finish the game, parceling the remainder of the work out among a grab bag of other programmers and artists, whoever had a few hours or days to spare.

Origin Systems was still populating the games with jokey cameos drawn from Richard Garriott’s friends, colleagues, and family as late as Ultima VI. Thankfully, this along with other aspects of the “programmer text” syndrome would finally end with the next installment in the series, for which a real professional writing team would come aboard. More positively, do note the keyword highlighting in the screenshot above, which spared players untold hours of aggravating noun-guessing.

Everyone at Origin felt the pressure by now, but no one carried a greater weight on his slim shoulders than Richard Garriott. If Ultima VI flopped, or even just wasn’t a major hit, that was that for Origin Systems. For all that he loved to play His Unflappable Majesty Lord British in public, Garriott was hardly immune to the pressure of having dozens of livelihoods dependent on what was at the end of the day, no matter how much help he got from Warren Spector or anyone else, his game. His stress tended to go straight to his stomach. He remembers being in “constant pain”; sometimes he’d just “curl up in the corner.” Having stopped shaving or bathing regularly, strung out on caffeine and junk food, he looked more like a homeless man than a star game designer — much less a regal monarch — by the time Ultima VI hit the homestretch. On the evening of February 9, 1990, with the project now in the final frenzy of testing, bug-swatting, and final-touch-adding, he left Origin’s offices to talk to some colleagues having a smoke just outside. When he opened the security door to return, a piece of the door’s apparatus — in fact, an eight-pound chunk of steel — fell off and smacked him in the head, opening up an ugly gash and knocking him out cold. His panicked colleagues, who at first thought he might be dead, rushed him to the emergency room. Once he had had his head stitched up, he set back to work. What else was there to do?

Ultima VI shipped on time in March of 1990, two years almost to the day after Ultima V, and Richard Garriott’s fears (and stomach cramps) were soon put to rest; it became yet another 200,000-plus-selling hit. Reviews were uniformly favorable if not always ecstatic; it would take Ultima fans, traditionalists that so many of them were, a while to come to terms with the radically overhauled interface that made this Ultima look so different from the Ultimas of yore. Not helping things were the welter of bugs, some of them of the potentially showstopping variety, that the game shipped with (in years to come Origin would become almost as famous for their bugs as for their ambitious virtual world-building). In time, most if not all old-school Ultima fans were comforted as they settled in and realized that at bottom you tackled this one pretty much like all the others, trekking around Britannia talking to people and writing down the clues they revealed until you put together all the pieces of the puzzle. Meanwhile Origin gradually fixed the worst of the bugs through a series of patch disks which they shipped to retailers to pass on to their customers, or to said customers directly if they asked for them. Still, both processes did take some time, and the reaction to this latest Ultima was undeniably a bit muted — a bit conflicted, one might even say — in comparison to the last few games. It perhaps wasn’t quite clear yet where or if the Ultima series fit on these newer computers in this new decade.

Both the muted critical reaction and that sense of uncertainty surrounding the game have to some extent persisted to this day. Firmly ensconced though it apparently is in the middle of the classic run of Ultimas, from Ultima IV through Ultima VII, that form the bedrock of the series’s legacy, Ultima VI is the least cherished of that cherished group today, the least likely to be named as the favorite of any random fan. It lacks the pithy justification for its existence that all of the others can boast. Ultima IV was the great leap forward, the game that dared to posit that a CRPG could be about more than leveling up and collecting loot. Ultima V was the necessary response to its predecessor’s unfettered idealism; the two games together can be seen to form a dialog on ethics in the public and private spheres. And, later, Ultima VII would be the pinnacle of the series in terms not only of technology but also, and even more importantly, in terms of narrative and thematic sophistication. But where does Ultima VI stand in this group? Its plea for understanding rather than extermination is as important and well-taken today as it’s ever been, yet its theme doesn’t follow as naturally from Ultima V as that game’s had from Ultima IV, nor is it executed with the same sophistication we would see in Ultima VII. Where Ultima VI stands, then, would seem to be on a somewhat uncertain no man’s land.

Indeed, it’s hard not to see Ultima VI first and foremost as a transitional work. On the surface, that’s a distinction without a difference; every Ultima, being part of a series that was perhaps more than any other in the history of gaming always in the process of becoming, is a bridge between what had come before and what would come next. Yet in the case of Ultima VI the tautology feels somehow uniquely true. The graphical interface, huge leap though it is over the old alphabet soup, isn’t quite there yet in terms of usability. It still lacks a drag-and-drop capability, for instance, to make inventory management and many other tasks truly intuitive, while the cluttered onscreen display combines vestiges of the old, such as a scrolling textual “command console,” with this still imperfect implementation of the new. The prettier, more detailed window on the world is welcome, but winds up giving such a zoomed-in view in the half of a screen allocated to it that it’s hard to orient yourself. The highlighted keywords in the conversation engine are also welcome, but are constantly scrolling off the screen, forcing you to either lawnmower through the same conversations again and again to be sure not to miss any of them or to jot them down on paper as they appear. There’s vastly more text in Ultima VI than in any of its predecessors, but perhaps the kindest thing to be said about Dr. Cat as a writer is that he’s a pretty good programmer. All of these things would be fixed in Ultima VII, a game — or rather games; there were actually two of them, for reasons we’ll get to when the time comes — that succeeded in becoming everything Ultima VI had wanted to be. To use the old playground insult, everything Ultima VI can do Ultima VII can do better. One thing I can say, however, is that the place the series was going would prove so extraordinary that it feels more than acceptable to me to have used Ultima VI as a way station en route.

But in the even more immediate future for Origin Systems was another rather extraordinary development. This company that the rest of the industry jokingly referred to as Ultima Systems would release the same year as Ultima VI a game that would blow up even bigger than this latest entry in the series that had always been their raison d’être. I’ll tell that improbable story soon, after a little detour into some nuts and bolts of computer technology that were becoming very important — and nowhere more so than at Origin — as the 1990s began.

(Sources: the books Dungeons and Dreamers: The Rise of Computer Game Culture from Geek to Chic by Brad King and John Borland, The Official Book of Ultima, Second Edition by Shay Addams, and Ultima: The Avatar Adventures by Rusel DeMaria and Caroline Spector; ACE of April 1990; Questbusters of November 1989, January 1990, March 1990, and April 1990; Dragon of July 1987; Computer Gaming World of March 1990 and June 1990; Origin’s in-house newsletter Point of Origin of August 7 1991. Online sources include Matt Barton’s interviews with Dr. Cat and Warren Spector’s farewell letter from the Wing Commander Combat Information Center‘s document archive. Last but far from least, my thanks to John Miles for corresponding with me via email about his time at Origin, and my thanks to Casey Muratori for putting me in touch with him.

Ultima VI is available for purchase from GOG.com in a package that also includes Ultima IV and Ultima V.)

Bernie

April 7, 2017 at 4:40 pm

Jimmy , I can’t thank you enough. More than an article, this is a gift from you to us.

When you answered my comment to to your last piece, I wasn’t expecting this one to come right after. What a pleasant surprise.

Bernie

April 8, 2017 at 9:43 pm

Sorry , about the “last piece” thing. I meant the “covert action” piece (the one before last really), where I used U6 to comment on the ludologists’ arguments.

whomever

April 7, 2017 at 5:13 pm

I actually really enjoyed Ultima VI, though it seems like it’s remembered as weaker than either V or VII. (Of course VIII is widely regarded as a disaster, I never even bothered finishing it). I’d be interested in if the way they were able to re-use the engine in both Savage Empire and Martian Dreams helped their bottom line. As to Origin’s habit of biting of more than they could chew, that was part of what made them a bit charming at the time. I do hope you’ll cover Strike Commander at some point! (The Assault Begins Christmas 1991, as the posters said).

Jimmy Maher

April 7, 2017 at 7:09 pm

Neither of the Ultimas VI spinoffs did terribly well…

Jonathan Badger

April 7, 2017 at 9:07 pm

Which was too bad, because they covered topics (pulp and steampunk) that rarely have been covered by other CRPGs

Chris Floyd

April 10, 2017 at 1:50 pm

They’re also different games: Adventure games built on an RPG engine (that’s how I would classify them, anyway). They split the difference between the coherent, single-minded story of an adventure game and the simulated world and sandboxy interactions of the Ultima RPGs. With half-hearted combat. I love those games, especially Martian Dreams. No one else will agree with me, but I think it’s Warren Spector’s masterpiece.

Jimmy Maher

April 10, 2017 at 2:07 pm

I think I’m going to have to take another look at them. I haven’t played them myself, and, based I confess partially on the CRPG Addict’s less-than-effusive reaction to them, I had planned to give them only somewhat cursory coverage. But the more I hear reactions like yours, the more intrigued I become.

Warren Spector, by the way, did make the uncharacteristically immodest claim that Martian Dreams was “the best damn Ultima game ever” while he was working on Serpent Isle. Not sure if he’d *still* agree that Martian Dreams is his masterpiece, but there’s that…

Chris Floyd

April 11, 2017 at 2:13 am

I’m so glad to hear Warren Spector loves Martian Dreams too. If you’re only going to play one, absolutely play that one. Savage Empire is good, but Martian Dreams easily outclasses it. If/when you play them, you have to keep in mind that they are clearly games with a very carefully controlled scope. They’re not ginormous living worlds; they’re worlds built to tell a particular story. Give them a try!

(Can I make a confession? I’m replaying Martian Dreams right now and I’m about 15m from completing it.)

Jimmy Maher

April 11, 2017 at 9:48 am

I’m a very narrative-focused — or goal-oriented — player, so this isn’t a problem for me. I give due credit to the “living world” aspects of the later Ultimas, but can’t say I spend a lot of time just messing around in them like some people do. If I’m baking bread or running a meat-distribution business or something, it’s only because I’m trying to earn money to accomplish something plot-related. Put it down to a lack of imagination. ;)

stepped pyramids

April 12, 2017 at 1:11 am

I love reading the Addict, but he’s definitely a man with particular tastes, and Martian Dreams is almost designed for him not to like it. He likes his RPGs on the crunchy/dungeon-crawly side and Martian Dreams is very close to being an adventure game. He also really dislikes that the Avatar changed from being a literal player representative to a particular character. And he seems to like his games on the more serious, grounded side and Martian Dreams is very pulpy and fantastical.

It’s still a good game with some enjoyable writing. Its main flaw is the clunky Ultima 6 engine and the vestiges of RPG combat it kept. The opening cinematic has a section that looks a lot like a LucasArts point-and-click adventure, and I think it would have made an incredible adventure game in that style.

I think the two Worlds of Ultima games together would be an interesting subject to cover, just because they’re games that attempted to expand the CRPG to fictional genres beyond fantasy, space opera, and the occasional cyberpunk. Martian Dreams in particular is a mixture of early SF, steampunk, and alt-history that is pretty much unlike anything else I’ve played.

Iffy Bonzoolie

June 1, 2020 at 8:33 pm

I won’t disagree. Martian Dreams is one of my favorite games of all time. Definitely an Adventure game first, built on an RPG engine. Combat is even more de-emphasized than in Ultima VI, for the better — even though I do enjoy tactical RPG combat.

Steven Marsh

April 7, 2017 at 5:37 pm

SPOILERS FOLLOW.

One of the challenges of reflecting on Ultima VI is that the core story is so . . . flat? . . . compared to other RPGs (even other aspects of the Ultima series). The twist is a cool one, but if you know it going in (which, as you note, was near-impossible not to do, back in the day), it just doesn’t feel that compelling.

Compared to the hooks of Ultima IV (“You need to become a paragon of the world!”), Ultima V (“Lord British is missing, and the world is oppressed!”), and even Ultima VII (“There’s an evil force who taunts you to stop him, whose power and reach is near-unknowable!”), it’s hard to get my juices flowing about the central hook of Ultima VI (“A species you’ve never seen before thinks you’re evil, but you’re not, but they’re not either, and . . . you need to fix it.”).

Similar stories sometimes get around this by having there be another compelling story that runs in parallel. For example, Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country has a fairly similar subplot, but the central story is discovering the truth behind the assassination of a Klingon and preventing the assassination of the Federation president . . . much more exciting stuff than is on display with Ultima VI.

(Typo alert: “almost year” — “almost a year”)

Jimmy Maher

April 7, 2017 at 7:17 pm

The complete lack of subquests in Ultima VI is perhaps part of the problem. This is another thing that Origin would do better in Ultima VII. There’s almost always something interesting to do locally as you follow the main plot across Britannia.

Thanks for the correction!

Robbie

August 4, 2021 at 6:19 pm

I remember reading that Spector intended for U6 to have side quests, but for some reason, Garriott decided that every single quest should be made mandatory for beating the story. That’s why the U6 campaign is basically made up of a bunch of fetch quests.

Jayle Enn

April 8, 2017 at 1:55 am

I was one of those people who managed to go in cold. I was young, couldn’t really afford industry mags, and that kind of thing. I still managed to suss out the core of the plot very quickly, and short-circuited the game to an absurd degree. I still enjoyed it, and it sold me a sound card, but the scope of (say) U5 just wasn’t there.

Odkin

April 10, 2017 at 1:49 am

Having played every Ultima since the first version of the first one, on the Apple II, Ultima VI was the end for me. Partly, I was being petulant about the interface changes and the loss of the Apple version. But VI also had changes, some of which you point out, that lessened the game experience for me. Despite being a young white male, the actual depiction on the Avatar as someone else really struck me at the time. And within the game, I REALLY missed the multiple points of view. I thought a great deal of intimacy was lost my maintaining one scale. Previously, you had a wide-view on the outside, a medium view in towns and in combat, and a close-up first person view in dungeons. The zooming in was proportional to your closeness of interaction. Dungeons SHOULD feel claustrophobic, not third-person and detached. You should feel like you’re IN them, not hovering above one with a glass ceiling.

Mike

January 8, 2020 at 3:59 am

The first computer game i played was Ultima 4 at the age of 6 or 7. Naturally i played all the later and former games in between the time of Ultima 4 and 7. They were a very magical thing to me. From the elaborate manuals and maps to the obscure “figure it out” gameplay. Needless to say When Ultima 7 came out (I was around 11 or 12) It was by far the best thing I had ever played or seen. Of course in a few short years other interests would consume me but nevertheless, it will always hold a special place in my heart and mind and I really can’t comment on it impartially .

On to the point. I think some peoples thoughts on certain games are very much breed from the time, place, and circumstance of which they first played them. Looking back now it is hard to defend some of the shortcomings of U7. I have tried in vain to replay it. But in my memory, its a 10/10.

Speaking of U6 I find it much easier to replay and appreciate. I think i might again.

Daev

April 7, 2017 at 5:48 pm

Thanks for another great article on gaming history, Jimmy. I’ve really been really been enjoying these lately.

Two spelling corrections: “systemitizing” should be “systematizing”, and “reign in” should be “rein in”.

Jimmy Maher

April 7, 2017 at 7:18 pm

Thanks!

Kai

April 7, 2017 at 6:30 pm

Having been introduced to the series with Ultima VII, I never managed to play any of the predecessors for more than a few hours, before either gameplay or controls made the experience sour for me. As such, I am quite happy to revisit them in the form of your blog (and it were your articles about some of the earliest Ultimas that brought me here in the first place!). After all, I think it is the lore and history accumulated over the course of the series that had its part in making the world of U7 so rich and believable, even if said history is shrewd and not always coherent.

And yeah, ever since I first came here, I’ve been looking forward to 1992 :-).

Jimmy Maher

April 7, 2017 at 7:25 pm

Yeah, for all its historical importance the Ultima series hasn’t aged terribly well in contrast to, say, the Infocom catalog. Most of the games come with lots and lots tedium attached. It really was a you-had-to-be-there sort of thing — although I do think Ultima I is surprisingly fun and playable today, if for no other reason than its sheer simplicity. I’d recommend that anyone but the seriously dedicated student of gaming history play Ultima I and Ultima VII and just read about the rest — unless, of course, you find one or both of those so entrancing that you just have to have more. ;)

MB

April 7, 2017 at 6:30 pm

Thanks for the reminder: I need to finish my playthrough of this classic series!

Dan Fabulich

April 7, 2017 at 7:49 pm

I don’t interpret the Compendium cover as gargoyles zapping the Ankh; it looks to me like the Ankh zapping the gargoyles. I can kinda see why you might think that the gargoyle on the left is shooting lighting, but note that the lighting forks away from the Ankh, not towards it. The gargoyle at the bottom center seems to be getting zapped in the back, and the gargoyle on the right has raised its left arm to shield its head. I think the gargoyle on the left is raising its hands to block, not to shoot.

Carl Muckenhoupt

April 8, 2017 at 12:56 am

I seem to recall that the game itself contains a more direct mirroring of the cover art: some sort of Gargoyle holy book bearing an illustration of a Gargoyle hero trampling the False Prophet (which is to say, the Avatar). The game doesn’t contain a graphical depiction of this, though; it’s only described in text.

Jimmy Maher

April 8, 2017 at 7:10 am

I could have sworn I read that the two illustrations were intended as the two sides of a coin, as it were, but now I can’t find it any of the sources I used. In light of that, I agree that it’s pretty indeterminate at best. Excised that bit.

Michael Davis

May 27, 2017 at 1:55 pm

I think the two-sides-of-the-coin device was what Carl said. When you are rescued by your companions in the animated introduction, Iolo loots the “Book of Prophecies” from the gargoyle priest he shot in the head, and on its cover is the mirror opposite of the front of the U6 game box: a triumphant gargoyle hero standing with one foot planted on a dead human.

http://ultima.wikia.com/wiki/The_Book_of_Prophecies

bryce777

April 7, 2017 at 8:41 pm

Ultima VI is definitely my favorite Ultima, and one of my favorite RPGs of all time.

Ultima I through III were OK but pretty primitive, not really worth playing if you did not play them when they came out. I don’t agree they required a giant slog and endless hours, but the fun factor/payoff is just not that great compared to a lot of later games. IV is highly overrated it is not really much different than I-III as far as I am concerned. V was a great game and a true leap forward, but it just doesn’t get to the same heights as VI as far as the gameplay and useability goes.

VII exceeded VI in most ways and the VO of the Guardian is fantastic but it also killed off the gameplay of VI by going to realtime. Once you play through it once there is not much point to do it again, as now it’s mainly just a game about exploration of the world more than a challenge unto itself. And VIII…I didn’t even bother due to jumping puzzles and other nonsense. I did try IX and it was quite a turkey. Every time you walk through an area you fight the same combat in the same spot over and over. Your weapons don’t penetrate many opponents easily, too. Now that was truly a slog. I did not bother too go very far with that one, it was probably the worst disappointment in gaming for me. Yet ironically I still think it’s better than a lot of similar first person “RPGs” to come out post 2000.

As far as writing goes, Ultima V is obviously the best by far. VI is not far behind though. Ultima VII does not have that good of writing, there is tons of nonsense especially with Batlin and other lame minor villains. I can see why people would mistake it as having good writing though, the situation is similar to with Irenicus in Baldur’s Gate 2. The villain is actually nonsensical and bizarre in BG II but the fantastic voice acting and cool look push it over the top into the realm of a classic (aside from the bizarre tree fight at the end that made no real sense). Guardian himself is written fine for the most part, but there is so much ancillary writing and design choices/railroading that is just kinda blah and strange departure from the previous installments.

Unfortunately the Ultima series is the Ultimate (hehe) reason why following the opposite philosophy of the SSI series is a huge mistake. Throwing your code away makes sense to me in that it will ensure you always have a fresh design, but this is highly unrealistic once you have larger game designs requiring man years of coding. Ultima series could have gone on indefinitely if they just scaled back slightly in budget and made incremental perfection of their game system after VI like Wizardry and Gold Box series. Ultima style of RPG in VI and VII had unlimited potential but in the end they threw it all away all too quickly once PC gaming became the norm.

Robbie

June 17, 2021 at 2:29 am

Nah. I played U1-3 for the first time in the late noughties and had lots of fun with them (well, except for U2).

You failing to connect with U4 doesn’t make it overrated. Contrary to what you claim, it’s not the same as previous games. The virtue system was extremely unique and set it apart from them (and from every other RPG) and it’s the very reason it’s held in such high regard. It completely changed the way the game was played and approached.

The real time gameplay was probably the greatest improvement brought about by U7. It made the world feel alive at last. It was like what U6 tried to be but didn’t quite manage thanks to the rather limiting turn-based system. That system wasn’t made for a game world intended to be fully interactive like U6’s.

Robbie

June 17, 2021 at 4:15 pm

I also disagree about the writing. U5’s dialogue was an improvement over 4’s but it was still super wooden, while 6 went the opposite way — it was over the top and kinda amateurish. 6’s story was quite baffling with its direction. It tries to paint the gargoyles as a misunderstood race that it’s not evil after all, yet it does little to make them come off as sympathetic. As soon as we visit their realm, we learn that winged gargoyles enslave the wingless ones, and try to justify themselves by claiming that the wingless are too dumb and need to be told what to do. Do I really need to explain how unsympathetic that sounds, not to mention its unfortunate implications? We also learn that most gargoyles don’t have their own names, instead being referred to by their job, making it clear that citizens are seen as pawns rather than individuals.

Do they really expect me to sympathize with a society like that and see nothing wrong with them?

bryce777

April 7, 2017 at 8:49 pm

Also, as I recall there is no end game plot twist. Or anyway it is dependent on how you play I guess. I found out pretty quickly the gargoyles were not really evil.

Also it’s worth pointing out that magic candle is probably the real influence on Ultima VI, not Dungeon Master. It copied MC in many other areas as well, like jobs and time schedules for people which I am pretty certain were not in Ultima V. Of course MC itself is obviously inspired by the Ultima series in the first place.

Blargh

April 8, 2017 at 2:11 pm

Wrong – Ultima V introduced day/night, weather (wind mechanics for ships), full NPC schedules.

bryce777

April 9, 2017 at 1:08 am

Thanks for correction, I have not played V since it came out.

bryce777

April 9, 2017 at 1:09 am

As far as story goes, I really liked the whole snake venom storyline as well. Writing can mean many things but what is so great in VII? I liked skara brae area in particular but most of the areas are kind of blah.

Captain Rufus

April 7, 2017 at 11:03 pm

I’m no fan of U6 but I still don’t understand the worship of 7. It’s just a terrible game in spite of being a technical masterpiece. Playing it however is like nearly all my issues with 6 brought forwards and mostly made worse thanks to real time and even more awful inventory management. 5 was the best Ultima got. Origin was more interested in what they could do as opposed to if it was fun. Which a lot of games have issue with.

Jimmy Maher

April 8, 2017 at 7:19 am

I think many of us who respond to Ultima VII do so on the basis of the writing. There’s an extraordinary amount of wit, warmth, and even wisdom in that game, largely thanks I think to head writer Raymond Benson, the unsung hero of the project. I’m a writer and a lover of good writing myself, so it’s no surprise I would respond to this so strongly; it’s not often I get to use words like “wit, warmth, and wisdom” in the context of CRPGs. If you don’t respond to the writing, I can see why you’d call Ultima VII, if not quite “terrible,” at least disappointing. As with most Ultimas, the mechanics are a little wonky, and the interface, while vastly improved over that of Ultima VI in my opinion, still leaves plenty to be desired by modern standards. As with so many games, your perception of Ultima VII is probably largely determined by what you go into it looking for.

But much, much more on all that when we get there.

stepped pyramids

April 12, 2017 at 1:15 am

I love Ultima VII’s writing. Wish I liked its plot more. Introducing an actual major villain to the Ultima series was an unfortunate idea.

Jimmy Maher

April 13, 2017 at 8:34 am

While I agree that the Guardian perhaps strays a bit too far into typical cackling-CRPG-villain territory, I think the Fellowship is handled with tons of subtlety and even compassion. The way they prey on people who are bereaved or feel alone in the world, enticing them with the promise of community and respect, rings very true. Also the way that the vast majority of the people in this “evil” cult really believe they’re a force for good in the world. My wife and I have been watching The Path lately, and there are some interesting parallels.

Alex Freeman

April 13, 2017 at 4:04 pm

I’ve read the Fellowship was actually modeled after Scientology. For what it’s worth, Charles Manson preyed on people the same way.

Robbie

June 17, 2021 at 2:19 am

Whereas I don’t get the U5 worship, and 7 is the best Ultima got. 5 felt like a transitional game. It had improvements over 4 like the introduction of the day/night cycle and NPC schedules, but then 6 and 7 took those improvements even further, while also adding more improvements that went with the design philosophy, like a more interactive world and the single-scale world. Compared to 6 and especially 7, 5’s world, dialogue, exploration and interactivity feel incredibly shallow.

Brain Breaker

April 7, 2017 at 11:27 pm

Hi Jimmy,

This is unrelated to this article, but I wanted to mention something you might find useful.

Checking out the sources you credit in your pieces, I noticed that the Computer Entertainer newsletter has never been listed. This small but amazing publication ran from 1982 (as the Video Game Update) to 1990. They were really on top of what was going on in the industry, and it’s probably the most detailed chronology of the entire US gaming scene from that crucial time. It’s also full of forgotten history that’s begging for further research. For instance, have you ever heard of Sierra’s failed mid 80s plans to release an ambitious multi-party RPG called Towers of Seven, or how they almost licensed The Black Onyx for US release? Neither had I, until I combed through Computer Entertainer, started cross-referencing minor mentions in other publications and put some of the pieces together.

I know you’re just now leaving this time period behind and entering the 90s here at Digital Antiquarian, but if you ever do go back and want to do further research (for a book, perhaps), I think you’d find it to be an invaluable resource. Unfortunately it’s still rather obscure and has only slowly gotten around online in a scatter-shot fashion, but scans of the (almost) complete run are out there, thanks to the efforts of game historian/preservationist Frank Cifaldi. I don’t know if links are permitted here, so just google it when you have the time. Sorry to go off topic here, but I thought it was worth mentioning.

So yeah, Ultima VI… Well… I preferred V and VII. And… That’s all I’ve got. :)

Jimmy Maher

April 8, 2017 at 7:26 am

Indeed, I’d never heard of this resource. I’ll definitely make a point of checking it out. Thanks so much!

Jayle Enn

April 8, 2017 at 1:59 am

The most… interesting bug I remember running into in U6 is one where the doors vanished. Doors and doorways, every room had a simple rectangular hole in the wall where the doors should be. I think it affected secret doors, as well.

…unfortunately, it also removed stairs and ladders and holes in the ground, which made all kinds of places completely inaccessible.

There were a few neat developer toys left in, too. There was an ASCII alt-sequence that would give you a larger-scale map, as if you’d used a magic gem, and talking to Iolo and saying ‘spam’ three times, then ‘humbug’ would give access to some sort of debugging interface that my friends and I never really figured out.

Marcus Johnson

April 11, 2017 at 4:01 am

The Cutting Room Floor has a pretty thorough run down of all the developer tools left in Ultima VII:

https://tcrf.net/Ultima_VI:_The_False_Prophet_(DOS)

Jubal

April 8, 2017 at 2:46 am

I hope you do cover Martian Dreams at some point – it’s the only Ultima game I’ve ever actually played properly…

As I recall, I rather enjoyed it at the time (c. 2001?) and the early steampunk setting was interesting in an era before it had been played to death.

Lisa H.

April 8, 2017 at 3:54 am

At the beginning of Ultima VI, the Avatar — i.e., you — is called backed to Britannia

Called back.

he drew equally triumphant Gargoyles zapping the Ankh, symbol of the Avatar and thus of all their suffering.

Hmm. I think given the body postures of the Gargoyles themselves that I agree with the other commenter who said the Ankh seems to be zapping the Gargoyles. The one at the left is perhaps ambiguous, but the two at the right and on the bottom seem to be in pain and/or attempting to defend themselves.

an eccentric character with strong furry tendencies

*gets on soapbox*

Yanno, being a furry really ain’t all that weird. By and large it’s a fandom not dissimilar from others. Some get pretty deep into it and play a specific animal character or animal representation of themselves, but that’s often not much different from being deep into a comic book fandom (e.g.). And even for those who take it quite seriously spiritually or as an identity, while certainly unusual, eh, I think this kind of distancing “oo er, minister” tone is not really necessary.

Jimmy Maher

April 8, 2017 at 7:32 am

I think “eccentric character with strong furry tendencies” is quite nonjudgmental. It provides a cogent explanation of just why this fellow might have ended up with the name “Dr. Cat” without launching into a digression or leaving the name hanging out there as a non sequitur. And, like it or not, I think most people would indeed consider furry fandom to be an eccentric — note that I didn’t choose the more pejorative “weird” — hobby. Nothing wrong with eccentric hobbies; most people would consider foregoing all those modern videogames that look better than real life in favor of creaky decades-old relics with pixels as big as your thumb to be pretty eccentric as well, and yet here I am, turning that into not just a hobby but a job description.

Thanks for the correction!

Watts

April 9, 2017 at 4:48 am

For what it’s worth, I didn’t take it as pejorative, and I’m the president of the Furry Writers’ Guild and have been a guest of honor at a couple furry cons. (And while I’ve only met him a couple times over the years, I’m not sure Dr. Cat would disagree with being described as an eccentric character.)

Carlton Little

April 10, 2017 at 6:40 pm

I dunno. I would say “furry” still has a social stigma that’s simply a different magnitude than, say, perusing electronic games as an adult. AFAIK, digital games are considered part of the mainstream these days. I’d even say comic books are fair play.

“Furry” seems to have other connotations. I don’t mean to offend anyone but that’s just what I’ve seen.

Brian Bagnall

April 9, 2017 at 2:22 am

You might be overstating things with this statement: “But, and while it’s understandable why Origin would want to keep things in the family, as it were, that’s more than a bit of a stretch. The real inspiration behind most of Ultima VI‘s interface innovations was FTL’s landmark 1987 CRPG Dungeon Master, a game whose influence on its industry can hardly be overstated.”

Compare a screenshot of Times of Lore to Ultima VI and look at the icons. Most of them are exactly the same, so I think it’s fair to say the icon control interface came from ToL.

The real stretch for me is where the article claims the non-zoomable unified world view is inspired by Dungeon Master. This is exactly how it is done in ToL, a game that was inspired by The Fairy Tale Adventure. I’ve played ToL start to finish and it’s exactly like Ultima VI. It even has the running commentary of your adventure, something TFTA also has. Even the artistic style is almost the same as ToL. I don’t see enough evidence to dismiss ToL as the influence while giving credit to Dungeon Master.

I think it would be more accurate to say the paper-doll interface was lifted from Dungeon Master, the rest was inspired by Times of Lore.

bryce777

April 9, 2017 at 3:57 am

Dungeon Master came before TOL but it’s not like they invented any real GUI concepts. those existed in software for some time, even back to the 70s. I highly doubt that games directly copied each other all that much, these were made by real programmers who were working in an industry that would almost certainly have exposed them to GUI design that was much more advanced than what the average PC and Apple user of the time had yet to encounter. When it became practical to apply it to games, they did so.

Jimmy Maher

April 9, 2017 at 8:30 am

Thanks for pushing back on this. I had another look at Times of Lore, and you’re right that I was being far too dismissive. Reworked those paragraphs to give a proper share of the credit to Times of Lore — and to that game’s progenitor The Faery Tale Adventure.

Brian Bagnall

April 10, 2017 at 3:50 pm

By the way, excellent coverage as usual. The real tragedy here is that your articles cause me to realize I need to go back and play certain games that I overlooked back then. I was entering university at the time and felt done with old toys so to speak, Ultima being one of them. Through your article I realized Ultima VI is basically Times of Lore (one of my all time favorites) but with much needed depth. I wish time wasn’t at such a premium these days.

AguyinaRPG

April 9, 2017 at 5:32 am

Personally I think that the way Ultima V opened up was appropriate, as it was meant to be a fish out of water story. It also pretty much expected you played IV, which is my favorite kind of sequel (see: Majora’s Mask).

U6 loses a bit of the magic, but I think it does well in providing an open-ended experience in ways that few prior games could facilitate. I remember in getting my first Rune I felt like I had missed out on so much, barely did any combat and found the person I was looking for fairly quickly. VII obviously takes this to the next level, but I think it’s fully formed enough to be worthwhile. The inventory issues also don’t bother me much, though that wasn’t something brought up in your criticism of the interface.

Do be kind to Dr. Cat. He’s quite proud of his work on the game, and I personally like that the script has a bit more enthusiasm to it than VII. Sure, I don’t think the meta nods need to be there, but a little levity is always welcome.

Gnoman

April 9, 2017 at 12:13 pm

I have to wonder how many people who are critical of Ultima VI played the (awful) C64 version. That computer just couldn’t handle it, but the port was, as far as I can tell, released.

Brian Bagnall

April 10, 2017 at 4:06 pm

A lot of people wonder how it got a 98% rating by Zzap!64:

https://archive.org/stream/zzap64-magazine-073/ZZap_64_Issue_073_1991_May#page/n53/mode/2up

It seems like the reviewer just covers the changes to the engine that would apply to all versions of Ultima VI but he didn’t talk about the C64 in particular. From what I’ve heard, the C64 version was slow and buggy. The Amiga version was also apparently pretty slow unless you ran it with a 68030 processor and installed it to a hard drive, but I haven’t confirmed that myself.

MagerValp

April 11, 2017 at 3:28 pm

It played well on a 14 MHz A1200 with Fast RAM and a hard drive, but it was an horrible on a 7 MHz A500 with floppies. Speaking from experience :)

TBD

April 18, 2017 at 5:58 am

I played on an Amiga 2000 with a hard drive and don’t remember any speed issues.

What I remember most about the game was what had stopped me playing – I went to the pub in Jhelom? where there was a sign telling me to leave all weapons at the entrance before entering.

I piled up all my weapons on the available benches, assuming the game would care, then proceeded to do some questing in the bar. When I finally left, I went to pick up my weapons but only the top weapons were still there. I had saved and reloaded my saved game and so lost a lot of my best weapons and stopped playing the game, intending to at some point get back into the game but start again.

I didn’t end up playing again until many years later on a PC after already completing both Ultima VII games and having the Ultima VI plot twist spoiled for me.

DerKastellan

June 1, 2020 at 7:55 am

I bought it in a store. It was horribly broken.

It required you to copy the game disks to play because it needed to modify the assets in place. It was destroying your game copy as you played it.

The publisher must not have gotten the memo as I never managed to copy the game disks – which strongly implies they were copy protected with the latest technology. Not even “bit copy” would do it.

The game was broken in many ways. They did not implement all spells. In order to open some metal doors you needed to bring super-heavy powder kegs as the explosion spell had not been implemented. Coins weighed ten times more than in the PC version to reduce memory use. And of course it looked abysmal in comparison and had none of the charm of “Ultima V” while not living up to “Ultima VI”, either.

I actually returned it once as broken to get two play-through attempts. Both failed.

Carlton Little

April 10, 2017 at 6:34 pm

Ultima 6 was my first Ultima. I discovered it quite by accident at a relatively young age. Even at that time, the graphics seemed quite primitive. But.. the things you could do in this game! I started out by just messing around, seeing what terrible things I could get away with.. stealing plates and cups at the dinner table, butchering the “butcher,” attacking Lord British. And getting lost in the dungeon underneath the castle. So many fond memories of getting lost in this immersive world!

The actual plot and progressing in the game.. seemed to be over my head for a long time. Every couple years I would go back to it and see if I could get any further. I guess I just wasn’t interested in taking notes and thusly ended up using walkthroughs to reach the endgame.

I still haven’t beaten the game without at least referencing a walkthrough a few times. So one of my goals remains to beat this game without any outside help. Now that Ultima 6 Nuvie is out–which removes much of the tedium of the interface–I think I’ll give it another go. Does anyone want to join me on this quest? ;)

Carl Muckenhoupt

April 10, 2017 at 6:51 pm

Having grown up with a PC rather than an Apple, U6 was the first Ultima I played. I remember being quite impressed with the sense of immensity it conveyed, although I did catch on that the terrain was made of a limited number of 8×8 chunks. (It was most obvious in the underground tunnels. Every dead end facing )

I was fairly isolated from the hype and didn’t have the twist spoiled, but found it fairly obvious all the same. Also, you talk about how the game leads you through the story, but it’s pretty easy for a new player, experimentally playing with the Orb of Moons, to skip straight from the beginning of the game straight to the Gargoyle lands with no idea of what they’re doing (and no way of communicating with the Gargoyles). Possibly seeing the endgame areas prematurely made the ending easier to anticipate? I don’t know.

Jimmy Maher

April 11, 2017 at 9:45 am

The open worlds of the later Ultimas do sometimes clash with the plots, even if you aren’t intentionally trying to “break” them. I remember visiting Moonglow on the trail of Elizabeth and Abraham in Ultima VII, finding Penumbra’s house there, and getting myself inside and awakening her because it was there and because everyone told me the Avatar was prophesied to do this. Suddenly she started asking me who had sent me, Nicodemus or the Time Lord. Nobody sent me, I wanted to say, and I have no idea what you’re talking about. But it wasn’t an option. Later I wound up finding the piece of the plot to which this all related.

Alex Freeman

April 11, 2017 at 5:15 am

Another great article! One your finest (that I’ve read at least)!

Nick

November 21, 2018 at 9:16 pm

Ultima6 was my first experience with the series. My father owned a computer store selling clones & we recieved the game on a used machine that came in on trade. I believe it was between 90 & 93. As soon as the game loaded up I was instantly hooked the vivid colors that were so new on computer screens seemed to leak into my soul. I was rather young, I recall being in the fourth grade. Anyhow, I had no idea what a RPG was or how to go about playing it (the day/night cycle really threw me, at first I thought it was a bug) stuck in Lord British’s castle (it was after all a semi-pirated copy) I spent days learning the controls & talking to every NPC in the castle trying to get out without the copy protection a.k.a. lord Brits Q’s & the compendium. I finally figured out how to break the copy pro by moving the avatar into a bag & then switching back to 1st player solo mode, ending up transported to frames, where I stole a powder keg & blew the door off the castle drawbridge. I probably spent more time in that game than any other since, I had no map so I set out with a ship & a sextant to map the oceans for myself. I had to reverse engineer the game map & then replay the game to figure out what the point was. I explored every inch of the map multiple times loving every second of it. That was almost 28 years ago & I still load the game every few months just to travel around Britannia a bit more. That game changed my life!

Iffy Bonzoolie

June 1, 2020 at 8:53 pm

One thing that Ultima VII does worse than VI is combat. It could be that combat was becoming less relevant in the series, and that’s fine. As an engine, though, 6 retains a deliberate, tactical combat mode, and combat in 7 is a chaotic mess. It would have been better to disable or tone down the frequency of combat than to replace the paradigm with full AI and real-time.

The fact that the game barely ran unless you had an expensive 486 also meant that real-time was likely a slide show where you couldn’t even make any decisions if the interface allowed it. You just had to hit ‘C’ and hope for the best.

Of course Westwood in Dune 2 figured out a reasonable RTS interface, used to good effect in Baldur’s Gate years later. In that sense, Ultima VII was in this nadir of CRPG combat system design. And VI, while not amazing, was still reasonably on one side of the valley.

Andreas

February 23, 2021 at 2:22 pm

As the world of Ultima VI was so rich there are a number of avenues that were presumably not planned for.

Simple example hack: locked door -> cast magic lock -> cast magic unlock -> unlocked door (without key).

Enter

“Things your mother never told you about Ultima 6”

http://www.it-he.org/ultima6.htm

My absolute aesthetic favorite is “cloning things for fun and profit”: the creative (ab)use of casting animate and clone (and then attacking your own creations); yes, that’s: mineral -> animal -> more animals -> more minerals!

Lhexa

April 24, 2021 at 6:03 pm

I’m ready to approach this entry. Let me explain why it is awful. In every previous entry on Ultima, you both taught me new facts about games I already had an encyclopedic knowledge of, and (for IV and V) revealed new facets I had not yet considered. So of course I eagerly awaited your entry on the single most important game of my childhood.

I learned nothing new. You repeated the prevailing narrative about Ultima VI without, as far as I could tell, deviating from it in any detail.