Then she generated the light, and the sight of her room, flooded with radiance and studded with electric buttons, revived her. There were buttons and switches everywhere — buttons to call for food, for music, for clothing. There was the hot-bath button, by pressure of which a basin of (imitation) marble rose out of the floor, filled to the brim with a warm deodorized liquid. There was the cold-bath button. There was the button that produced literature. And there were of course the buttons by which she communicated with her friends. The room, though it contained nothing, was in touch with all that she cared for in the world.

— from “The Machine Stops” by E.M. Forster

If we wished to compare The Source with CompuServe’s MicroNET in their earliest days, we might say that the former emphasized the content it would provide to its subscribers while the latter planned to set its subscribers free to make their own content for themselves. In a later era, the World Wide Web would offer both of these things in a hundred-car pileup between the forces of traditional media and millions of empowered creative individuals; we as societies are still struggling in many ways to come to terms with the sea change this represents. It’s of course the second part of the equation — all those empowered creative individuals — that marks the real diversion from the top-down media models of old. One might thus be tempted to say that MicroNET’s approach was the more visionary, hewing as it seemingly does to the philosophy sometimes known as “Web 2.0,” that guiding light of “mature” Internet culture. To do so, however, might be to give Jeff Wilkins and his colleagues a bit too much credit. The real driving force behind Wilkins’s MicroNET had little in common with the ideas that would come to be labelled Web 2.0, or for that matter the academic research that led to Web 1.0.

Wilkins had seen that computers were entering homes for the first time, but, raised on the big iron of institutional computing as he was, he couldn’t help but observe how absurdly primitive these new microcomputers really were. He thought of MicroNET as a way for people saddled with such toy computers to use them as the gateway to a real computer. Thus MicroNET’s early emphasis on programming languages. Why should hobbyists content themselves with the primitive BASIC dialects, 16 K (or less) memories, and slow and unreliable cassette-based storage of the first generation of microcomputers when MicroNET could offer them the chance to write and run larger programs in more sophisticated languages like Fortran and Pascal?

It didn’t take long, however, to see that most subscribers didn’t in fact come to MicroNET looking for a replacement for their little home computers. They rather saw it as a place to talk about the things they were doing on their micros: a place to trade tips, rumors, and ideas with one another. They were, in other words, less interested in writing programs on CompuServe’s big computers than they were in using them as a communications tool — as a way of learning how to write better programs on the TRS-80s and Apple IIs sitting right in front of them. Users groups were springing up all over the country for much the same purpose, but, valuable as they were, they were bound by all the constraints geography imposed on what was still a very small hobby in a very big country. What did you do between the monthly meetings of your users group? Some hobbyists logged onto MicroNET to get their fix of shop talk. And so, while the online programming environments sat largely unused, the email system and the public message boards were soon full of activity.

For all that this wasn’t quite what Wilkins had envisioned when he set up MicroNET, he adjusted to the reality on the ground with admirable alacrity. The first sign of the changing times came as early as December of 1979, when a new area called the “MicroNET Software Exchange” made its debut. Representing CompuServe’s first substantial investment of programming effort just for MicroNET subscribers, it was modeled after initiatives like the TRS-80 Software Exchange that was run by Softline magazine. With the commercial-software industry still in its infancy, these so-called “exchanges” gave programmers a conduit for selling their home-grown creations to the public. From the entrepreneurs whose wares could be found on them would be born many of the first generation of full-service software publishers — among them names like VisiCorp, Brøderbund, and Adventure International.

The MicroNET Software Exchange went online with 17 TRS-80 programs on offer, ranging in price from $1 to $49, with an average of $16.40. Subscribers who indulged could download the programs they purchased right away, seeing the price conveniently tacked onto their next MicroNET bill. But by the time MicroNET Software Exchange launched it was already clear to astute observers that this means of loosey-goosey commercial-software distribution — it wasn’t unusual for a single developer to “publish” the same program through half a dozen exchanges — probably wasn’t long for this world, doomed by the very same professional software publishers they had done so much to spawn. Despite the appeal to immediate gratification that downloading offered over waiting for physical cassettes to come in the mail, the MicroNET Software Exchange never took off. The era of digital download as a means of commercial-software distribution would require many years yet to come to fruition; this was one aspect of the digital life of the future that would indeed have to wait for a future that came equipped with the fast and reliable connections needed to download complex software painlessly.

Still, the MicroNET Software Exchange did point to Wilkins’s evolving view of the service, just as the effort that went into creating it pointed to how MicroNET as a whole was moving out of the experimental phase, ready to take its place as an actively developed part of CompuServe’s business model. CompuServe began to take out some modest advertisements for the service in magazines like InfoWorld, and in the summer of 1980 dropped the separate MicroNET moniker altogether. The consumer online service was now known simply as CompuServe, all the former reticence about mixing corporate and consumer business in the same organization shoved aside. Many people within the company remained unhappy about the push into the consumer marketplace, but Wilkins dealt with the developing culture clash by isolating his small team of consumer-service developers in an office of their own, far from the jeering of their colleagues. Helping his cause immensely was the fact that Sandy Trevor, who had replaced John Goltz as the company’s chief technical architect, was himself an enthusiastic supporter of the consumer service, sending the skunk-works group many of his keenest technical minds. With him leading the way, almost all of the technical staff came around in fairly short order, and in time the rest of the staff would follow — especially as the consumer service started making the company real money. By 1987, it would constitute half of CompuServe’s revenue, nicely offsetting the continuing slow decline in the corporate time-sharing market.

It is true that early on the consumer side of the company grew fairly slowly; it would take until well into 1981 for it to reach 10,000 subscribers. Yet its perceived importance, both inside and outside of CompuServe, developed much more quickly. On May 12, 1980, the accounting giant H&R Block bought CompuServe in a deal which left Jeff Wilkins in charge and promised to let him continue on the path he was already steering. Wilkins himself believed that the potential of the consumer service was a major motivating factor — if not the major factor — prompting H&R Block to make the deal. He told one interviewer at the time that he believed H&R Block wanted “to put themselves in a marketplace that is growing faster than the tax markets.” Needless to say, such a description no longer applied to corporate time-sharing services, now a stagnant rather than an exploding market.

Radically different though the two companies’ histories, industries, and cultures were, the acquisition led to surprisingly little internal friction. Wilkins used the sense of security the name of H&R Block lent in corporate America to make deals for the consumer service that may very well have been impossible otherwise, while H&R’s deep pockets and willingness to take the long view made it possible for him to expand on his already excellent telecommunications network, thereby making sure that when the users were ready to come to CompuServe en masse, CompuServe would have the pipes to accept their business. “You have to have the ability to anticipate, to be two or three years ahead of the market,” said Wilkins. By mid-decade, it would be possible to establish a rock-steady connection with CompuServe’s PDP-10s in Columbus via a local call from virtually anywhere in the country.

The telecommunications infrastructure wasn’t the only aspect of the consumer service that required the constant attention of Wilkins’s best engineers. The steadily growing user roll brought plenty of challenges to the programming staff as well. In the old days, when CompuServe had been strictly a provider of time-sharing to corporate clients, each client was earmarked to a certain PDP-10 machine in the pool of same inside the data centers; said machine stored all their data and ran all their software and was thus the only one they needed to access. The demands of the consumer service, however, soon extended beyond the capacity of any one machine. Dividing subscribers into pools and assigning them to individual machines was no good solution, for all of the subscribers needed to be able to interact with one another in ways which CompuServe’s corporate clients didn’t. Sandy Trevor was the key designer of what came to be called the “yo-yo switch,” a methodology for balancing the load of the consumer service across the company’s range of twenty or more PDP-10s. Trevor:

When a user logs onto CompuServe and selects an option from the menu, he or she is automatically connected with the host on which the needed data is stored. If during an online session he later selects another item that’s on a different computer, he is quickly switched over to that host. Because it’s done so quickly, [the] user is unaware of the change.

This very divorcement of the details of computing hardware from computing in the abstract — to such an extent that the user never needs to think about the hardware at all — is the source of the adjective “cloud” in the modern notion of cloud computing. In the early 1980s, it was at the cutting edge of computer science, and points to how groundbreaking the CompuServe of that time was in a strictly technical as well as social and business sense.

While the engineers were thus occupied on the technical end, CompuServe’s evolving marketing department developed ways to get the service in front of potential customers with what one might call an engineer’s single-minded precision. In the summer of 1980, CompuServe struck a deal with Radio Shack, who were selling far more home computers than anyone else at the time, to stock what came to be known as the “Snapaks”: packets containing everything a new subscriber needed to log into the system for the first time and set up an account. A customer could go from opening the packet to using the service within minutes. The Snapaks thus represented a potent force in the consumer marketplace: instant gratification.

From store shelves, the Snapaks found their way into modem boxes, as well as those housing most of the popular home computers. Just as software publishers had long since realized that a stunning percentage of software was purchased at the same time as the computer used to run it, CompuServe understood that the best way to capture a potential customer was to nab her early, in the first blush of excitement that accompanied taking her new toy home. Thanks to their connections and financial resources, no one else could rival them in this kind of outreach. It became a key part of their success, especially after the inevitable competition in the market for online consumer services — some of it far more dangerous than the moribund The Source — began to arrive by mid-decade.

But we perhaps get ahead of ourselves; that’s a story for my next article. At this point, I’d like to flip the script on this business history with which we’ve occupied ourselves until now. It’s time to put on a social historian’s hat and ask what the people who used this most popular and sophisticated of all the 1980s online services were actually doing when they logged on.

It turns out that much of it wasn’t all that far removed from what people still do online today. That fact, far from minimizing the importance of this pioneering service, only serves to underscore how prescient it really was. Humans are, as the cliché goes, social animals. “Social media” may not yet have been a term, but as early as 1980 CompuServe was evolving into a prime example of exactly that. Advertised as a service, it very quickly became a community.

From the beginning, of course, there was email, allowing CompuServe members to send private messages back and forth for any reason they liked. Already in November of 1981, 80 Computing magazine could write of this subtly disruptive technology that “it may replace the postal system and take part of the load now carried by the telephone.”

While the concept of email — still generally referred to during the 1980s by more long-winded sobriquets like “electronic mail” — is a fairly obvious one, the fundamental issue which held back its acceptance as a replacement for paper mail for many years was the lack of inter-operability between the various email systems. For a CompuServe subscriber, this meant that she could only send and receive email to and from other CompuServe subscribers. In one of those quotations that become retroactively hilarious, Marvin Weinberger, a computer researcher, mused thus in 1984:

What we need is a sort of “Long Lines” carrier for electronic mail. It would be analogous to AT&T’s Long Lines, which transmits a message among the local telephone operating companies. So far, a few vendors have taken steps to exchange messages, but there are hundreds of mail systems. If electronic mail is really to become as useful as the telephone — meaning one could send a message to anybody, anywhere — then an entity of this type is a prerequisite.

Weinberger was overlooking the Internet, an entity of exactly the needed type which already existed and was in fact being used to exchange email all over the world as he said those words. Indeed, his words sound like the beginning of a joke: “Gee, if only there was an open computer network already in place for the purpose of sending all these data packets back and forth…”

But the Internet’s evolution into the publicly accessible World Wide Web was still years away; in 1984, it was available only to those with the right university, government, or corporate connections. In the meantime, the closed email systems of services like CompuServe did much to trap subscribers on the service with which they had originally signed up. Each online service was such a closed universe in all respects that moving from one to another meant literally abandoning one’s friends.

While email was a great tool for communicating with friends you’d already made on CompuServe, how did you make new ones? How, in other words, could you find people on CompuServe in the first place who shared your interests? The solution to this problem, arrived at already in its most basic form in 1980, were things that were first known as “Special Interest Groups,” then re-branded with the pithier moniker of simply “Forums.” Rather than dividing CompuServe’s offerings by function — email, bulletin boards, etc. — the Forum system divided them by topic. In a Forum, one could find and communicate with other subscribers who, one knew, were also there out of interest in the Forum’s topic.

Predictably enough, the earliest Forums tended to be dedicated to the computing hobby itself. Each brand of computer and, soon, each viable model of computer got its own Forum. These gatherings of like-minded subscribers came to wield considerable influence in the computer industry at large. Apple’s John Sculley and Steve Wozniak, for instance, both made themselves personally available from time to time on the Forum known as the “Micronetworked Apple Users Group.” It wasn’t unusual for journalists from the magazines to source their word-on-the-street reports from the CompuServe Forums, which came to serve them well as early harbingers of the way the public at large would react to any given plan, product, or announcement. Radio Shack developed the TRS-80 Model 100, the world’s first reasonably usable laptop computer, practically in partnership with the TRS-80 Forum. First they took the time to ask the people there what they wanted in a portable computer. Then they delivered prototype models to the Forum’s leading lights and collected their feedback — rinse and repeat through several more cycles. Throughout the process, the executives behind the project remained consistently available to the Forum’s members. The early subscribers to CompuServe were by definition trailblazers, and the people marketing home-computer hardware and software took their influence very, very seriously.

With time, though, CompuServe’s user base began to branch out beyond the hardcore hacker demographic, and the Forums reflected this in their growing diversity of subject matter. Jeff Wilkins has named aviation as the first non-computer topic to really take hold. Pilots, who were often early technology adopters, had congregated in enough numbers on CompuServe within a year or two that their pooled information on airplanes, airports, weather, and traffic became one of the best resources any aviator could have. Still more pilots started signing up for CompuServe just to have access to this goldmine, creating a snowball effect.

And as aviation went, so in time went heaps of other hobbies and topics of interest: law, medicine, gardening, religion, sports, travel, individual authors and musicians. Just as journalists in our own time have developed a sometimes disconcerting Twitter dependency, journalists by 1986 were finding a fair number of their alleged scoops on CompuServe. When the space shuttle Challenger blew up during launch in January of that year, the huge and active NASA Forum, with plenty of members perched at a privileged vantage point inside NASA itself, became the place to find the latest news about what had happened and why. By 1989, more than 170 Forums were in operation.

The real genius of the Forum system was CompuServe’s willingness to allow them to be driven by ordinary subscribers — a willingness that hearkens back in its way to the founding philosophy of the service. Recognizing that they couldn’t possibly administer such a diverse body of discussions, CompuServe’s employees didn’t even try. Instead they created a process whereby new Forums could be formed whenever enough subscribers had expressed interest in their proposed topics, and then turned over the administration to the experts, the people who knew best the topics they dealt with: the very same subscribers who had lobbied for them in the first place. Forum administrators — known as “sysops” in CompuServe parlance — were given free access, along with a cash stipend that was dependent on how active their domain was. For the biggest Forums, this could amount to a considerable amount of money. Jeff Wilkins has claimed that some sysops wound up earning up to $250,000 in the course of their CompuServe life.

Sysops enjoyed broad powers to go with their compensation. It was almost entirely they who wielded the censor’s pen, who said what was and wasn’t allowed. As their Forums grew, they were permitted to hire deputies to help them police their territory, rewarding them with gifts of free online time. By all accounts, the system worked remarkably well as an early example of the sort of community policing on which websites like Wikipedia would later come to depend. It was a self-regulating system; those few sysops who neglected their duties or abused their powers could expect their Forum’s traffic to dwindle away, until CompuServe shut the doors. Those Forums with particularly enthusiastic and active sysops, on the other hand, thrived, sometimes out of all seeming proportion to their esoteric areas of interest. The Source, still hewing largely to its content- rather than user-driven model, failed to implement anything like the Forum concept until 1985, and was rewarded with a far more fragmented, far less active social space, even taking into account the growing disparity between the numbers of subscribers on the two services.

While the Forums were instrumental in making CompuServe what it was, it was a single technical rather than administrative development which did the most of all to bind CompuServe’s subscribers together into a real community — a development which stands out today as the most obviously, undeniably groundbreaking aspect of the entire service.

The consumer service’s formative period had been marked by a brief-lived but fairly intense craze for CB radio, fueled by corn-pone entertainments like Smokey and the Bandit, B.J. and the Bear, and The Dukes of Hazzard. For a while, cars sporting huge antenna rigs were a common sight on American highways, and truckers were left grumbling about all these amateurs muddying up their bandwidth. Radio Shack made a killing off the fad, selling CB kits in their stores alongside the TRS-80s that were fueling the contemporaneous early home-computer boom. The people who found CB radio interesting were very often the same ones who were buying computers and using them to log onto CompuServe.

In late 1979, in the midst of the CB craze, CompuServe rolled out an addition to the operating system used on their time-sharing PDP-10s: a method of sharing segments of memory across multiple user sessions. It may not sound like the most exciting innovation, but it opened up worlds of new possibilities for direct, user-to-user interaction in real time. The synergy between CB enthusiasts and the computer enthusiasts on CompuServe inspired Sandy Trevor to use his programmers’ latest advance in the service of a real-time online chat system. “It struck me that CB was something everyone had heard of,” he would later say. “Unlike many computer concepts, it wasn’t difficult for novices, and I thought it would provide a unique environment for meeting other people.” Jeff Wilkins recalls his first glimpse of what become known as “CB Simulator”:

We had an executive-committee meeting every Monday morning at 9:00; this was for the whole company. Sandy Trevor came to me before the meeting and said, “I want to show you what I did over the weekend. I call it CB. You pick a channel and you pick a username and you type, and everybody that’s on your channel sees what you’re typing.” He demonstrated it for me. I said, “Wow, that’s really interesting. I don’t know if people will use it or not, but we’ll give it a try and see. Let’s tell the executive committee about it, see what they think.”

So, we went to the executive-committee meeting and he gave a demonstration. I’ll never forget the expressions on their faces. They said, “You guys are insane! Nobody will ever use that! Why are we wasting our time on all this goofy stuff?”

Despite the committee’s objections, CB Simulator went live on February 21, 1980, with no fanfare whatsoever. CompuServe didn’t advertise it at all during its first four years of existence, and it wasn’t even on the menu system for the first year; would-be chatters had to learn the command to activate it from their more clued-in online friends. Sandy Trevor claims that this manifest ambivalence was shared by even Wilkins himself to a degree that’s perhaps obscured by the quotation above; “Jeff Wilkins,” he says, “thought it would be a fad.”

And yet CB Simulator went on to become CompuServe’s killer app, the place where the majority of subscribers spent the majority of their online time. A modern-day Wilkins, long since disabused of any doubts he might once have harbored, calls it out as the perfect combination of “high-tech” and “high-touch”; CB Simulator, more so than even the Forum system or anything else on CompuServe, provided that personal element that turned a conduit for information into a conduit for relationships. CompuServe’s advertising copy — after, that is, they bothered to start advertising CB Simulator — stated the case with only slight hyperbole: “There are students, lawyers, pilots, doctors, engineers, housewives, programmers, writers, all ready to welcome you from the moment you first access CB and type, ‘Hello, I’m new.'” For the people who used it, CB Simulator wasn’t a program or a service or even a technology; it was a social space where, once you’d learned the handful of needed commands, the technology quickly faded into the background.

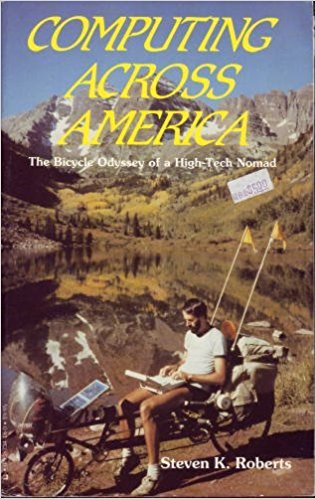

Steven K. Roberts received a great deal of press attention for his two-and-a-half year trip across the highways and byways of the United States on his high-tech bicycle. On the cover of his book, he’s shown using a Tandy/Radio Shack portable computer — part of a model line designed, appropriately enough, in partnership with CompuServe subscribers — to connect to CompuServe via a satellite uplink. He was a CB Simulator regular throughout his adventure.

For most people of the 1980s, the idea of having online friends was still a deeply odd one, but for the people who were part of the CB Simulator scene the relationships forged there were as real and as pure as any they formed in the “real” world — or perhaps in many cases even more so. One regular chatter noted that on the CB Simulator “you meet someone from the inside out. You judge them on their heart and values, not what kind of jeans they wear.” Pat Phelps, CompuServe’s longtime CB Simulator administrator, beloved to the point of being called “Mother Superior” by her charges, spoke of the doors that were opened in similarly utopian terms:

There is no king or queen or worker class to it. Everyone is totally equal; it’s a fantastic equalizer as far as social order goes. It doesn’t matter what sex or race you are or what you look like, or handicaps, or whatever. People judge you on your ideas, on how you communicate.

Many handicapped people, for example, can’t leave their homes, and they’re withdrawn and concerned about the way they look. Here’s a way they can meet new people, make friends from all over the country. It doesn’t matter if they’re handicapped because everyone is accepted for the thoughts they share over the computer. If you meet a person who doesn’t fit the image of what you thought they should look like, it doesn’t matter because you already care for them and accept them.

“It’s like having a house guest in the corner who will talk to you anytime you want,” said another chatter. “It’s a form of communication, like hanging out on a street corner.” But of course many of the people hanging out on this virtual street corner were the very sort who would have been extremely uncomfortable doing so in the real world. “I’ve always been a loner, and this is a convenient way to meet people,” said one. “For the first time in my life, I have a group of people I can communicate with anytime.”

One of the first of many CB Simulator parties was organized by Pat Phelps in Columbus on June 16, 1984. These happy dancers have for the most part never met before in the physical world — but they seem to be getting along well enough.

Some of the friendships that were forged on CB Simulator evolved into something more — and this even before the “lonely hearts” channels became a thing. Pat Phelps claimed that even during the earliest period of CB Simulator’s existence several couples who met there wound up getting married. Although they were almost certainly not the absolute first of their kind, the first well-documented instance of a couple who met online getting married dates to February 14, 1983.

George Stickles and Debbie Fuhrman were better known online as “Mike” and “Silver.” He was a 29-year-old who worked at a copy shop near Dallas, Texas, she a 23-year-old secretary from Phoenix, Arizona. They got to know each other by chatting for “five or six hours” every night; “He would type in these jokes on the computer, and I felt really comfortable,” said Fuhrman. She eventually moved to Dallas to be with him. As a tribute to their unusual courtship, they decided to hold a wedding online, where their other friends on CB Simulator could participate. At first they thought of only a mock marriage. “Then after we got into it,” said Fuhrman, “we decided, why not do it for real. Pat [Phelps] said, ‘Yeah, yeah, by all means, do it for real.’ So we decided to go ahead and do everything at the same time.” The online spectators included Fuhrman’s parents, who had been unable to travel from Phoenix to join their daughter and future son-in-law. The bridesmaid was named Cupcake, the caterer “<< >>,” the usher Gandalf, the photographer Challenger, while the best man was the perfectly named Bestman. Three computers were placed in the same room in Dallas: one for each half of the happy couple, one for a 24-hour on-call minister who had been plucked out of the local phone book. As they went through the ceremony, each typed his or her words in addition to speaking them aloud. “I was quite surprised at the number of people who attended, as well as how well everything went,” said Stickles. The couple left the ceremony in a hail of virtual rice: “***************************.”

Stickles and Fuhrman were interviewed a number of times by journalists interested in documenting this strange new phenomenon of online dating. Some of the other adventures and misadventures their articles describe still ring true to anyone who has dipped a toe in these waters:

A couple who had been communicating over the lines for two months decided to meet each other at a local bar. They had been talking on the phone earlier. “The phone conversation was marvelous,” says the woman, who goes by the handle BigGal. “We chatted, laughed, and conversed for the better part of three hours. I couldn’t believe such a human being existed.”

And then they met. Damion, who had claimed to be 6 feet tall, had “mysteriously shrunk to about 5 feet 6 inches,” says BigGal. “The well-built body I had imagined assumed an avocado shape, and what was left of his brown hair was more of a dull, dusty gray color. Damion, supposedly 24 to 27 years old, also fibbed about his age. He looked old enough to be my father.”

Anecdotes like these reveal that judging the opposite sex exclusively on “their hearts and values” only got some chatters so far.

Still, we can presume that some of the supposed dishonesty that could lead to misunderstandings arose not so much from malignant intent as an earnest desire to try on different identities that weren’t going to fly in many real-world regions of an intensely hetero-normative country. One chatter told a journalist of some intense online time spent with what he assumed to be a “lovely, very philosophical” woman — only to learn that she was “really” a guy named Dave. Was Dave engaging in dishonest behavior, or revealing a truer self — or was Dave in some sense doing both at once?

Inevitably, some people were less interested in the relationship-building aspect of the whole romantic enterprise than they were in getting right down to the sex. Channels dedicated to sex chat could be found on CB Simulator almost from the beginning, and were quietly tolerated by CompuServe’s administrators — if not, for obvious reasons, publicized. Below is a precious historical document: real footage from 1984 of one of CB Simulator’s “adult” channels, as preserved by YouTube user Mathew Melnick. From the common area shown on the video, chatters could pair up in private rooms in order to… well, you know what they were doing, don’t you?

So, this sort of thing certainly had its place on CB Simulator. But, particularly after the media latched onto the topic of online sexy talk with predictable enthusiasm, it didn’t take long for the very sort of uncomfortable exchanges so many women had seen CB Simulator as an escape from to begin to spill over into their online life as well. Indeed, this became one of the few topics on which the usually sanguine Pat Phelps expressed real worry:

CompuSex is a very small part of what the medium is about. I’m not against it. If people want to do that, it’s perfectly alright. But now, because of the publicity, the majority of women have gotten extremely shy. Most of them aren’t even going to “talk” mode anymore. I don’t do it anymore, unless it’s with someone I know, because most of the one-on-ones are sex calls now. It’s kind of shut the door to friendships and meeting new people. Many of the women I talked to felt the same way. It’s sad. It’s shutting the door against the real reason that CB was originated in the first place, for fun and friendship and camaraderie and romance.

Thus, already by the time Phelps said those words in 1984, the Garden of Eden that had been CB Simulator in the eyes of its first adopters was starting to collect its share of snakes.

Other chatters were less predatory, but just as depressing in the way they brought some of the less savory aspects of the real world with them online. The head of the Republican Forum, speaking from the vast wisdom she had accrued in her 24 years, seemed determined to live up to every stereotype about her political party when she sniffed that “usually CB people are more educated, make a little more money. They’re a better group of people.” It all served to point out, for anyone who was in doubt, that the online life of the future wouldn’t be all unicorns and rainbows. If everyone was equal on CB Simulator, it seemed that some still believed they were more equal than others.

Another discordant note was lent by a new phrase which had begun to enter journalistic parlance for the first time by 1984: “online addiction.” The phrase is still heard all too often today, but one big difference between then and now is that those using CompuServe and similar services during the 1980s were paying by the minute for the privilege. Lurid stories emerged, usually based on hearsay rather than direct reporting, describing chatters who had supposedly lost house and home to the compulsion. While the scope was perhaps often exaggerated, the problem for some people was real. Monthly bills of $500 or more weren’t unusual among the CB Simulator hardcore, who occasionally confessed to forgoing niceties like a new car to replace that beat-up old clunker in order to have the money to keep chatting.

But there are downsides to any social revolution. The fact remains that the people hanging out on CB Simulator and other online spaces like it were at the vanguard of something extraordinary, something destined to be far more a force for good than its opposite. For countless people, home-bound or otherwise isolated by circumstance from those in the physical spaces around them, CompuServe became a vital part of their existence. I have no statistics to hand on how many people didn’t take their own lives or make some other tragic decision because of CompuServe, but I strongly suspect they number more than a few. Born as a prosaic exercise in corporate time-sharing, CompuServe’s evolution into the largest and most vibrant online community of the 1980s — it could boast 500,000 active members by 1989 — is one of the more unlikely and inspiring tales of a pivotal era in computer history. As yet, though, we’ve only seen half the picture. Next time, we’ll see how Big Media went digital for the first time thanks to CompuServe.

(Sources: the books On the Way to the Web: The Secret History of the Internet and its Founders by Michael A. Banks and Computing Across America: The Bicycle Odyssey of a High-Tech Nomad by Steven K. Roberts; Creative Computing of March 1980; InfoWorld of May 26 1980, March 14 1983, July 2 1984, July 9 1984, July 23 1984, and July 30 1984; 80 Microcomputing of November 1980 and November 1981; Online Today of June 1985 and July 1989; Alexander Trevor’s brief technical history of CompuServe, which was first posted to Usenet in 1988; interviews with Jeff Wilkins from the Internet History Podcast and Conquering Columbus.)