Monarchy is like a splendid ship. With all sails set it moves majestically on, but then it hits a rock and sinks forever.

— Fisher Ames

In The Republic, that most famous treatise ever written on the slippery notions of good and bad government, Plato describes what first motivated people to willingly cede some of their personal freedoms to others. He writes that “a state arises, as I conceive, out of the needs of mankind; no one is self-sufficing, but all of us have many wants. Can any other origin of a state be imagined?”

Even in relatively primitive civilizations, the things that need doing outstrip the ability of any single individual to learn how to do them. From this comes specialization, that key marker of civilization. But for specialization to work, a civilization needs a marketplace — a central commons where goods and services can be bought, sold, and traded for. Maintaining such a space, and resolving any disputes that arise in it, requires a central authority. And then, as the fruits of specialization cause a civilization to rise in the world, outsiders inevitably begin to think about taking what it has. Thus a standing army needs to be created. So, already we have the equivalents of a Department of Justice, a Department of Commerce, and a Department of Defense. But now we have another problem: the people staffing all of these bureaucracies, not to mention the soldiers in our army, don’t themselves produce goods and services which they can use to sustain themselves. Thus we now need an Internal Revenue Service of some sort, to collect taxes from the rest of the people — by force, if necessary — so that the bureaucrats and the soldiers have something to live on. And so it continues.

I want to point out a couple of important features of this snippet of the narrative of progress I’ve just outlined. The first is that, of all forms of progress, the growth of government is greeted with the least enthusiasm; for most people, government is the very definition of a necessary evil. At bottom, it becomes necessary because of one incontrovertible fact: that what is best for the individual in a vacuum is almost never what is best for the collective. Government addresses this fundamental imbalance, but in doing so it’s bound to create resentment in the individuals over whom it asserts control. Even if we understand that it’s necessary, even if we agree in principle with the importance of regulating commerce, protecting our country’s borders, even collecting funds to help the young, the old, the sick, and the disadvantaged, how many of us don’t cringe a little when we have to pay the taxman out of our own hard-earned wages? Not for nothing do the people of almost all times and all countries feel a profound ambivalence toward their entire political class, those odd personality types willing to baldly seek power over their peers. Will Durant:

If the average man had had his way there would probably never have been any state. Even today he resents it, classes death with taxes, and yearns for that government which governs least. If he asks for many laws it is only because he is sure that his neighbor needs them; privately he is an unphilosophical anarchist, and thinks laws in his own case superfluous.

The other thing that bears pointing out is that, even though they make up two separate departments in a university, political science and economics are very difficult to pull apart in the real world. Certainly one doesn’t have to be a Marxist to acknowledge that it was commerce that gave rise to government in the first place. In Plough, Sword, and Book, his grand sociological theory of history, Ernest Gellner writes that “property and power are correlative notions. The agricultural revolution gave birth to the exchange and storage of both necessities and wealth, thereby turning power into an unavoidable aspect of social life.” The interconnections between government and economics can be tangled indeed, as in the case of a descriptor like “communism,” technically an economic system but one which, in modern usage at least, presumes much about government as well; a phrase like “communist democracy” rings as an oxymoron to ears brought up in the Western tradition of liberal democracy.

In this light, we can probably forgive the game of Civilization for lumping communism into its list of possible systems of “government” for your civilization, as I hope you’ll be able to forgive me for discussing it in this pair of articles on those systems. (The article that follows this pair will address other aspects of economics in Civilization.) Each of Civilization‘s broadly-drawn governments provides one set of answers to the eternally fraught questions of who should have power in a society, what the limits of that power should be, and whence the power should be derived. As such, they lend themselves better than just about any other aspect of the game to systematic step-by-step analysis. So, that’s what I want to do in this article and the next, looking at each of the six in turn, asking, as has become our standard practice in this series, what we can learn about the real history of government from the game and what we can learn about the game from the real history of government.

That said, there are — also as usual — complications. This is one of the few places where Civilization rather breaks down as a linear narrative of progress. You don’t need to progress through each of the governments one by one in order to be successful at the game. In fact, just the opposite; many players never feel the need to adopt more than a couple of the six governments over the course of their civilization’s millennia of steady progress on other fronts. Likewise, depending on which advances they choose to research when, players of Civilization may see the various governments become available for adoption in any number of different orders and combinations.

And then too, unlike just about every other element of the game, the effectiveness of the governments in Civilization can’t be ranked in ascending order of desirability by the date of their first appearance in actual human history. If that was the case, communism — or possibly, as we shall see, anarchism — would have to be the best government of all in the game, something that most definitely isn’t true. Government just doesn’t work like that, in history or in the game. Democracy, for example, a form of government inextricably associated with modern developed nations and the likes of Francis Fukuyama’s end of history, is actually a very ancient idea. Given this, I’ve hit upon what feels like a logical method of my own for ordering Civilization‘s systems of government here, in a descending ranking based on the power and status each system in its most theoretical or idealized form vests in its leader or leaders. If that sounds confusing right now, please trust that my logic will become clearer as we move through them.

I do need to emphasize that this overview isn’t written even from 30,000 feet, but rather from something more akin to a low orbit over a massively complicated topic. Do remember as you read on that these strokes I’m laying down are — to mix some metaphors — very broad. I’m well aware that our world has contained and does contain countless debatable edge cases and mangy hybrids. That acknowledged, I do believe that setting aside the details of day-to-day politics and returning to first principles of government, as it were, might just be worthwhile from time to time.

Despotism is the most blunt of all political philosophies, one otherwise known as the law-of-the-jungle or the Lord of the Flies approach to governance. It states simply that he who is strong and crafty enough to gain power over all his rivals shall rule exactly as long as he remains strong and crafty enough to maintain it. For whatever that period may be, the despot and the state he rules are effectively one and the same. Regardless of what the despot might say to justify his rule, in the end despotism is might-makes-right distilled to its purest essence.

“Every state begins in compulsion,” writes Will Durant. In the formative stages of any civilization, despotism truly is an inevitability. In a society with no writing, no philosophy, no concept of human rights or social justice, no other form of government could possibly take hold. “Without autocratic rule,” writes the philosopher and sociologist Herbert Spencer, “the evolution of society could not have commenced.”

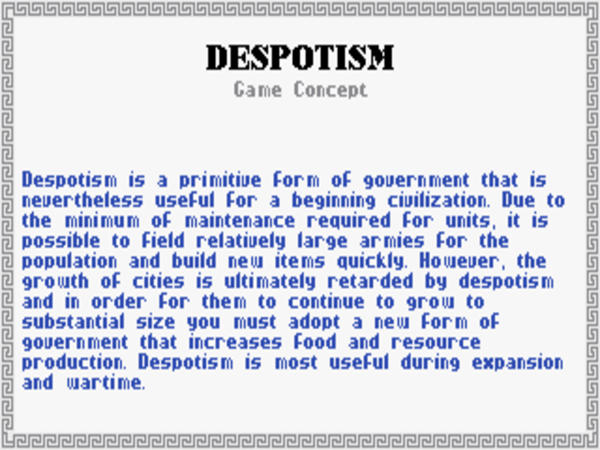

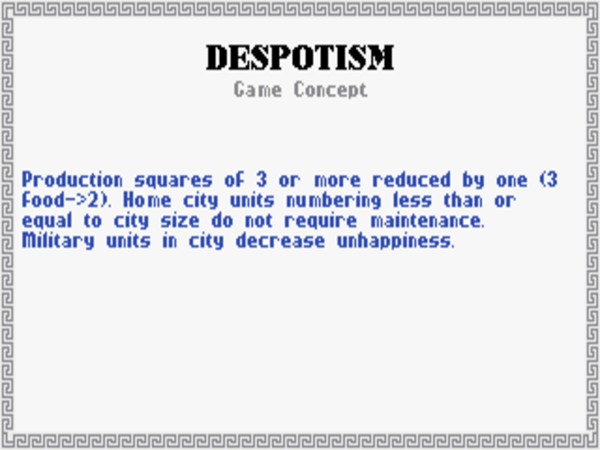

So, it’s perfectly natural that the game of Civilization as well always begins in despotism. In the early stages of the game especially, absolute power has undeniable advantages. Aristotle considered all of the citizens under a despotic government to be nothing more nor less than slaves, and that understanding is reflected in the way the game lets you form them into military units and march them off to war without having to pay them for the privilege, nor having to worry about the morale of the folks left behind at the home front. The military advantages despotism offers are thus quite considerable indeed. If your goal in the game is to conquer the world rather than climb the narrative of progress all the way to Alpha Centauri, you can easily win while remaining a despot throughout.

Yet the game does also levy a toll on despotism, one which, depending on your strategy, can become more and more difficult to bear as it continues. Cities under despotism grow slowly if at all, and are terrible at exploiting the resources available to them. If you do want to make it to Alpha Centauri, you’re thus best advised to leave despotism behind just as quickly as you can.

All of which rings true to history. The economy of a society that lives in fear — a society where ideas are things hated and feared by the ruling junta — will almost always badly lag that of a nation with a more sophisticated form of government. In particular, despotism is a terrible system for managing an industrial or post-industrial economy geared toward anything but perpetual war. Political scientist Bernard Crick:

Most autocracies (and military governments) are in agrarian societies. Attempts to industrialize either lead to democratization as power is spread and criticism is needed, or to concentrations of power as if towards totalitarianism but usually resulting in chronic economic and political instability. The true totalitarian regimes were war economies, whether at war or not, rejecting “mere” economic criteria.

Although the economic drawbacks of despotism are modeled, the structure of the game of Civilization doesn’t give it a good way of reflecting perhaps the most crippling of all the disadvantages of despotism in the real world: its inherent instability. A government destined to last only as long as the cult of personality at its center continues to breathe is hardly ideal for a real civilization’s long-term health. But in the game, the notion of a ruler outside yourself exists not at all; you play a sort of vaguely defined immortal who controls your civilization through the course of thousands of years. Unlike a real-world despot, you don’t have to constantly watch your back for rivals, don’t have to abide by the rule of history that he who lives by the sword shall often die by the sword. And you don’t have to worry about the chaos that ensues when a real despot dies — by natural causes or otherwise — and his former underlings throw themselves into a bloody struggle to find out who will replace him.

For the ruthless power-grabbing despot in the real world, who’s in this only to gratify his own megalomaniacal urges, this supposed disadvantage is of limited importance at best. For those who live on after him, though, it’s far more problematic. Indeed, a good test for deciding whether a given country’s government is in fact a despotic regime is to ask yourself whether it’s clear what will happen when the current leader dies of natural causes, is killed, steps down, or is toppled from power. Ask yourself whether, to put it another way, you can imagine the country continuing to be qualitatively the same place after one of those things happens. If the answer to either of those questions is no, the answer to the question of whether the current leader is a despot is very likely yes.

It would be nice if, given the instability of despotism as well as all of the other ethical objections that accompany it, I could write of it as merely a necessary formative stage of government, a stepping stone to better things. But unfortunately, despotism, the oldest form of human government, has stubbornly remained with us down through the millennia. In the twentieth century, it flared up again even in the heart of developed Europe under the flashy new banner of fascism. Thankfully, its inherent weaknesses meant that neither Mussolini’s Italy, Hitler’s Germany, nor Franco’s Spain could survive beyond the deaths of the despots whose names will always be synonymous with them.

And yet despotism still lives on today, albeit often cloaked under a rhetoric of pseudo-legitimacy. Vladimir Putin of Russia, that foremost bogeyman of the modern liberal-democratic West, one of the most stereotypically despotic Bond villains on the current world stage, nevertheless feels the need to hold a sham election every six years. Peek beneath the cloak of democracy in Russia, however, and all the traits of despotism are laid bare. The economic performance of this, the biggest country in the world, is absolutely putrid, to the tune of about 7 percent of the gross national product of the United States, despite being blessed with comparable natural resources. And then there’s the question of what will happen in Russia once Putin’s gone. Tellingly, commentators have been asking that very question with increasing urgency in recent years, as “Putin’s Russia” threatens to become a descriptor of an historical nation unto itself not unlike Hitler’s Germany.

The inventors of monarchy — absolute rule by a single familial lineage rather than absolute rule by a single individual — appear to have been the ancient Egyptians. Its first appearance there in perhaps as early as 3500 BC marks an early attempt to remedy the most obvious weakness of despotism, the lack of any provision for what happens after any given despot is no more. It’s not hard to grasp where the impulse that led to it came from. After all, it’s natural for any father to want to leave a legacy to his son. Why not the country he happens to rule?

At the same time, though, with monarchy we see the first stirrings of a concern that will become more and more prevalent as we continue with this tour of governments: a concern for the legitimacy of a government, with providing a justification for its existence beyond the age-old dictum of might-makes-right. Electing to go right to the source of all things in the view of most pre-modern societies, monarchs from the time of the Egyptian pharaohs claimed to enjoy the blessing of the gods or God, or in some cases to be gods themselves. In the centuries since, there has been no shortage of other justifications, such as claims to tradition, to a constitution, or just to good old superior genes. But more important than the justifications themselves for our purposes is the fact that they existed, a sign of emerging sophistication in political thought. Depending on how compelling those being ruled over found them to be, they insulated the rulers to a lesser or greater degree from the unmitigated law of the jungle.

In time, the continuity engendered by monarchy in many places allowed not just a ruling family but an extended ruling class to arise, who became known as the aristocracy. Ironically for a word so overwhelmingly associated today with inherited wealth and privilege, “aristocracy” when first coined in ancient Greece had nothing to do with family or inheritance. The aristocracy of a society was simply the best people in that society; the notion of aristocratic rule was thus akin to the modern concept of meritocracy. We can still see some of this etymology in the synonym for “aristocrat” of “noble,” which has long been taken to mean, depending on context, either a high-born member of the ruling class or a brave, upright, trustworthy sort of person in general; think of Rousseau’s “noble savages.” (The word “aristocrat” hasn’t been quite so lucky in recent years, bearing with it today a certain connotation of snobbery and out-of-touchness.)

Aristocrats of the old school were one of the bedrocks of the idealized theory of government outlined by Aristotle in Politics; an “autocracy” ruled by true aristocrats was according to him one of the best forms of government, although it could easily decay into what he called “oligarchy.” Yet the fact was that ancient Greece and Rome were every bit as obsessed with bloodlines as would be the wider Europe in centuries to come, and it didn’t take long for the ruling classes to assert that the best way to ensure the best people had control of the government was to simply pass power from high-born father to high-born son. Whether under the ancients’ original definition of the word or its more modern usage, writes the historian of aristocracy William Doyle, “the essence of aristocracy is inequality. It rests on the presumption that some people are naturally better than others.” For thousands of years, this presumption was at the core of political and social orders throughout Europe and most of the world.

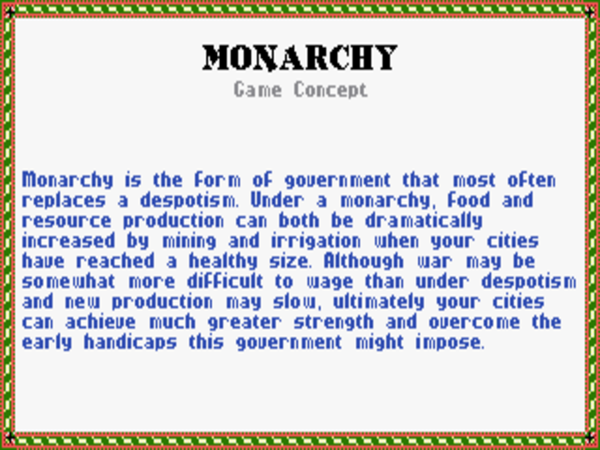

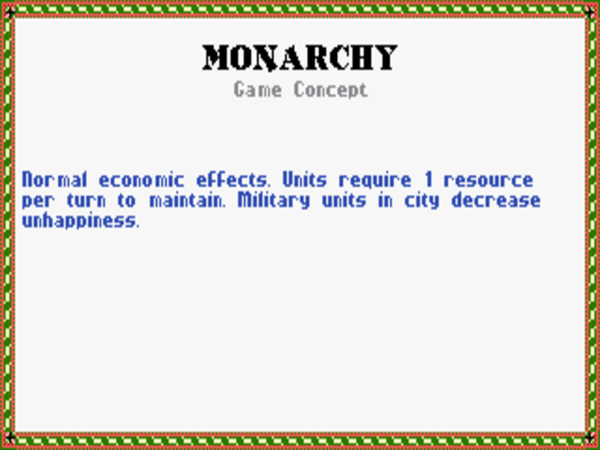

“Monarchy seems the best balanced government in the game,” note Johnny L. Wilson and Alan Emrich in Civilization: or Rome on 640K a Day. And, indeed, the game of Civilization takes monarchy as its sort of baseline standard government. Your economy is subject to no special advantages or disadvantages, reflecting the fact that historical monarchies have tended to be, generally speaking, somewhat less tyrannical than despotic governments, thanks not least to a diffusion of power among what can become quite a substantial number of aristocratic elites. This is a good thing in economic as well as ethical terms; a population that spends less time cowering in fear has more time to be productive. But it does mean that the player of the game needs to pay more to maintain a military under a monarchical government, a reflection of that same diffusion of power.

Once again, though, Civilization‘s structure makes it unable to portray the most important drawbacks of monarchy from the standpoint of societal development. A country that employs as a philosophy of governance such a system of nepotism taken to the ultimate extreme is virtually guaranteed to wind up in the hands of a terrible leader within a few generations — for, despite the beliefs that informed aristocratic privilege down through all those centuries, there’s little actual reason to believe that such essential traits of leadership as wisdom, judgment, forbearance, and decisiveness are heritable. Indeed, the royal family of many a country may have wound up ironically less qualified for the job of running it than the average citizen, thanks to a habit of inbreeding in the name of maintaining those precious bloodlines, which could sometimes lead to unusual incidences of birth defects and mental disorders. The ancient Egyptians made even brother-sister marriages a commonplace affair among the pharaohs, and were rewarded with an unusual number of truly batshit crazy monarchs.

Thus even despotism has an advantage over monarchy in the quest to avoid really, really bad leaders. At least the despot who rises to the top of the heap through strength and wiles has said strength and wiles to rely on as ruler. The histories of monarchies tend to be a series of wild oscillations between boom and bust, all depending on who’s in charge at the time; if Junior is determined to smash up the car, mortgage the house, and invest the family fortune in racehorses after Daddy dies, there’s not much anyone can do about it. Consider the classic example of England during the Renaissance period. The reigns of Elizabeth I and James I yielded great feats of exploration and scientific discovery, major military victories, and the glories of Shakespearean theater. Then along came poor old Charles I, who within 25 years had managed to bankrupt the treasury, spark a civil war, get himself beheaded, and prompt the (brief-lived) abolition of the very concept of a King of England. With leadership like that, a country doesn’t need external enemies to eat itself alive.

The need for competent leadership in an ever more complicated world has caused monarchy, even more so than despotism, to fall badly out of fashion in the last century; I tend to think the final straw was the abject failure of the European kings and queens, almost all of whom were in family with one another in one way or another, to do anything to stop the slow, tragically pointless march up to World War I. Monarchies where the monarch still wields real power today are confined to special situations, such as the micro-states of Monaco and Liechtenstein, and special regions of the world, such as the Middle East.

In Europe, for all those centuries the heart of the monarchical tradition, a surprising number of countries have elected to retain their royal families as living, breathing national-heritage sites, but they’re kept so far removed from the levers of real political power that the merest hint of a political opinion from one of them can set off a national scandal. I confess that I personally don’t understand this desire to keep a phantom limb of the monarchical past alive, and think the royals can darn well turn in the keys to their taxpayer-funded palaces and go get real jobs like the rest of us. I find the fondness for kings and queens particularly baffling in the case of Scandinavia, a place where equality has otherwise become such a fundamental cultural value. But then, I grew up in a country with no monarchical tradition, and I am told that maintaining the tradition of royalty brings in more tourist dollars than it costs tax dollars in Britain at least. I suppose it’s harmless enough.

The notion of a certain group of people who are inherently better-suited to rule than any others is sadly less rare than non-national-heritage monarchies in the modern world. Still, because almost all remaining believers in such a notion believe the group in question is the one to which they themselves belong, such points of view have an inherent problem gaining traction in the court of public opinion writ large.

Of all the forms of government in Civilization, the republic is the most difficult to get a handle on. If we look the word up in the dictionary, we learn little more for sure about any given republic than that it’s a nation that’s not a monarchy. Beyond that, it can often seem that the republic is in the eye of the beholder. In truth, it’s doubtful whether the republic should be considered a concrete system of government at all in the sense of its companions in Civilization. It’s become one of those words everyone likes to use whose real definition no one seems to know. Astonishingly, more than three-quarters of the sovereign nations in the world today have the word “republic” somewhere in their full official name, a range encompassing everything from the most regressive religious dictatorships to the most progressive liberal democracies. Growing up in American schools, I remember it being drilled into me that “the United States is a republic, not a democracy!” because, rather than deciding on public policy via direct vote, citizens elect representatives to lead the nation. Yet such a distinction is not only historically idiosyncratic, it’s also practically pointless. By this standard, no more than one or two real democracies have ever existed in the history of the world, and none after ancient times. Such a thing would, needless to say, be utterly impossible to administer in this complicated modern world of ours. Anyway, if you really insist on getting pedantic about definitions, you can always use the term “representative democracy.”

I suspect that the game of Civilization‘s inclusion of the republic is most heavily informed by the ancient Roman Republic, which can be crudely described as a form of sharply limited democracy, where ordinary citizens of a certain stature were given a limited ability to check the powers of the aristocracy. Every legionnaire of the Republic had engraved upon his shield the motto “Senatus Populusque Romanus”: “The Senate and the People of Rome.” Aristocrats made up the vast majority of the former institution, with the plebeians, or common people, largely relegated to a subsidiary role in the so-called plebeian tribunes. The vestiges of such a philosophy of government survive to this day in places like the British Parliament, with its split between a House of Lords — which has become all but powerless in this modern age of democracy, little more than yet another living national-heritage site — and a House of Commons.

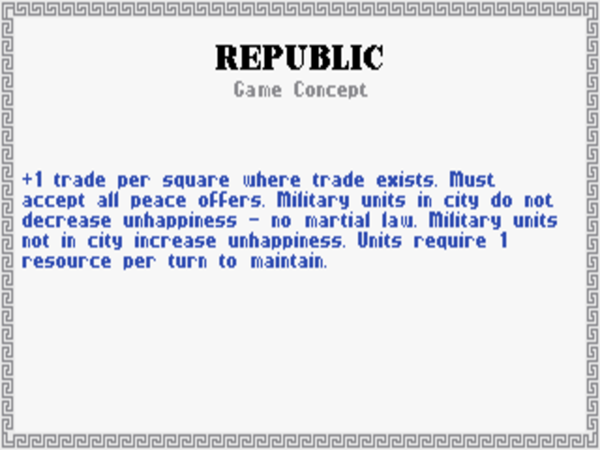

In that same historical spirit, the republic in the game functions as a sort of halfway point between monarchy and democracy, subject to a milder form of the same advantages and disadvantages as the latter — advantages and disadvantages which I think are best discussed when we get to democracy itself.

I don’t want to move on from the republic quite yet, however, because when we trace these roots back to ancient times we do find something else there of huge conceptual importance. Namely, we find the idea of the state as an ongoing entity unto itself, divorced from the person or family that happens to rule it. This may seem a subtle distinction, but it really is an important one.

The despot or the monarch for all intents and purposes is the state. Thus the royal we you may remember from Shakespeare; “Our sometime sister, now our queen,” says Claudius in Hamlet in reference to his wife, who is also the people’s queen. The ruler and the state he rules truly are one. But with the arrival of the republic on the scene, the individual ruler is separate from and — dare I say it? — of less overall significance than the institution of the state itself. He becomes a mere caretaker of a much greater national legacy. This is important not least because it opens the door to a system of government that prioritizes the good of the state over that of its leaders, that emphasizes the ultimate sovereignty of the state as a whole, in the form of all of the citizens that make it up. It opens the door to, as John Adams famously said after the drafting of the American Constitution, “a government of laws and not men.” In other words, it makes the philosophy of government safe for democracy.

(Sources: the books Civilization, or Rome on 640K A Day by Johnny L. Wilson and Alan Emrich, The Story of Civilization Volume I: Our Oriental Heritage by Will Durant, The End of History and the Last Man by Francis Fukuyama, The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt by Toby Wilkinson, The Republic by Plato, Politics by Aristotle, Plough, Sword, and Book: The Structure of Human History by Ernest Gellner, Aristocracy: A Very Short Introduction by William Doyle, Democracy: A Very Short Introduction by Bernard Crick, Plato: A Very Short Introduction by Julia Annas, Political Philosophy: A Very Short Introduction by David Miller, and Hamlet by William Shakespeare.)

Alex Freeman

April 27, 2018 at 5:27 pm

Another great article! Again fascinating to read how order emerges from chaos and the trajectory it takes once it’s formed.

It makes sense despotism would be the order that initially emerges from the chaos of warring tribes and the phenomenon of accumulated wealth. Whether or not it’s merely a necessary stepping stone to better things, inequality in general seems to be the inevitable result of accumulated wealth:

https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg23831740-400-the-origins-of-sexism-how-men-came-to-rule-12000-years-ago/

I have suspected monarchy was intended to promote stability, but it’s particularly interesting to see that aristocracy was originally supposed to be a meritocracy.

I don’t agree with your statement that there’s little actual reason to believe that such essential traits of leadership as wisdom, judgment, forbearance, and decisiveness are heritable, though. Even though being related to someone with those traits is no guarantee you’ll have them, it still significantly improves your chances of having them. The genes we inherit play a huge role in shaping how our minds work.

Laertes

April 27, 2018 at 9:13 pm

Maybe being raised by such a person is more important that genes, but I don’t have data to back it up.

Jimmy, you mentioned Franco along with Mussolini and Hitler, like them he started (or joined one in the case of Mussolini) a war that destroyed his country, but unlike them he died peacefully in his old age after almost 40 years of rule. At least were fortunate enough not have another civil war after his death (I am spanish).

And yes, we have a monarchy as well, but I agree with you. I’d really like to see how having one is bringing tourists dollars.

Jimmy Maher

April 28, 2018 at 6:40 am

Yes, my point wasn’t that all despots die violent deaths — although I would guess that their life-insurance premiums are quite high — but rather that the lack of a way of *legitimizing* a transfer of power under despotism means that a chaotic scramble always ensues after their death to figure out what happens next. Thankfully, it was peaceful and led to a better system of government in Spain. That is, alas, far from the usual case. The cult of personality just doesn’t work terribly well as a basis for stable government.

Now that I think about it, the only monarchy that I actually *know* to bring in lots and lots of tourist dollars is the one in Britain. Made an edit. Thanks!

Damon

April 28, 2018 at 10:00 pm

If dictators can survive their first 18 months (or thereabouts) they often have very long rules.

I found The Dictators Handbook excellent at explaining how just about any form of government seeks to rule if it can get away with it. One of the best books on politics I’ve ever read:

https://www.amazon.com/Dictators-Handbook-Behavior-Almost-Politics/dp/1610391845

Now that I’ve posted this I’ll have to read my copy again to refresh my memory on the salient points.

Anyone living in a democracy should read this to be aware just how power is manipulated and controlled by ambitious leaders.

Matyas

April 28, 2018 at 5:05 pm

Yeah, it can be argued that being taught from an early age to be an effective ruler would make the descendant more suitable to the task than the average person. Makes me wonder how things would have worked out in a monarchy where the most capable son (or daughter) would be the heir instead of the firstborn son.

As an aside, Jimmy, according to your definitions, would you class North Korea as a monarchy?

Jimmy Maher

April 28, 2018 at 6:11 pm

Mm, I wouldn’t quite call it a monarchy because the familial order of succession isn’t codified into law that I know of. The scramble for power that followed the death of Kim Jong Un’s father, with him killing anyone who might be a threat to him, certainly smacks of pure despotism. A monarchical system usually — but by no means always — manages to avoid that sort of thing. But it’s also very typical of communist states in the real world — as distinguished from communism as conceived by Karl Marx, with which said states tend to have surprisingly little beyond rhetoric to do. More on that in the next article. ;)

Alex Freeman

April 28, 2018 at 6:21 pm

Well, I’d say it’s technically more accurate to say North Korea is stuck in the “dictatorship of the proletariat” phase, which Karl Marx thought would be brief.

Jimmy Maher

April 28, 2018 at 6:43 pm

Well, the whole phenomenon of twentieth-century communism was a self-serving corruption of Marx’s theories. He explicitly state that an agrarian economy, which North Korea was at the time of the Korean War, *is not ready* to become communist under any circumstances, that it must first pass through the intermediate stages of industrial capitalism and socialism. He used the phrase “dictatorship of the proletariat” only a couple of times, and never really defined what he envisioned when he did. The ironic thing about Marx is that he wrote far more words about capitalism than communism. But more on that in the next article. ;)

whomever

May 1, 2018 at 3:24 pm

I would argue that North Korea bears some similarity with the Roman Empire. It was not really “Technically” a monarchy (And in fact they never never used the word “Rex”, “King” due to the Roman legacy of having previously thrown their monarchy off pre-Republic). Sometimes the Emperor was a descendent, sometimes a random person picked behind the scenes, sometimes conquest. Of course, North Korea hasn’t been around very long. Monarchies tend never to be quite “pure” in terms of always going to the next descendent; civil wars and the like happen. An interesting case is the Ottomans, where the Sultan’s mother was a non-Muslim slave in the Harem. Meant they didn’t get inbred if nothing else, though they were notorious that the first thing you do upon getting the crown was get rid of your siblings.

stepped pyramids

May 4, 2018 at 4:35 am

It’s certainly not uncommon for rulers in formally hereditarian monarchies to chop off a lot of heads to make sure everyone knows who the boss is, and many historical monarchies didn’t technically have it written down anywhere that the monarch’s firstborn child succeeds to the throne.

Hereditary succession is actually pretty uncommon in communist states. It never happened in the USSR itself, or in China. Cuba had the transfer of power to Raul Castro, but that kind of maneuver is hardly unheard of in non-communist states. Other than that, North Korea is absolutely unique among purportedly communist nations in having hereditary rulership. NK is not “real communism” in a way that goes beyond any kind of argument along those lines for the USSR, China, Cuba, etc.

Simon_Jester

October 10, 2022 at 1:19 pm

Coming back to this a lot later (to the point where it arguably qualifies as historical hindsight), Raul doesn’t seem to have had any dynastic ambitions, and handed over power to a more conventionally structured government.

I won’t comment on whether the Cuban government c. 2022 is “democratic” or a party oligarchy; I’ve heard arguments both ways. But Cuba’s definitely not shaping up to be a ‘Castro dynasty.’

stepped pyramids

May 4, 2018 at 4:38 am

@Alex Freeman: What Marx referred to as the “dictatorship of the proletariat” is something that’s up for debate — there’s a good argument that he didn’t mean anything close to what we currently identify with the word “dictatorship” — but setting that aside, it’s hard to argue that the Kim family is in any way representative of the proletariat. The USSR had a pretense of being a worker’s state up until the end, but North Korea pretty much gave up on that in the early Kim Jong Il era.

@whomever made my earlier point about monarchies better than I did. I should have read more before posting. :)

Simon_Jester

September 20, 2022 at 3:09 am

I’m coming to this much later, but I can’t help but make some comments here, because this comment thread has sparked a lot of thoughts about Civilization’s government system, and that of the closely related Civ II which is nearly identical.

Monarchies in which any son could inherit the throne are actually quite common in world history. There were multiple dynasties of Roman emperors who would just pick someone not even related to them and adopted them as a son. The Ottomans and Mughals would enable any son of the previous sultan to rule… with the rather problematic custom that the new sultan was at least well-advised and sometimes expected to kill off his brothers to limit the competition, resulting in regular short sharp civil wars and a LOT of intrigue. Plenty of other monarchies have had flexibility in identifying the heir.

The trick is that none of these systems reliably created perfected optimized custom-trained super-monarchs.by hand-raising them from birth. That doesn’t seem to work out reliably in practice. Probably because the potential benefits of carefully training someone to rule from a young age are offset by disadvantages. Among these:

1) Everyone with long range plans is courting the heir’s favor from an early age, which results in them being influenced by a lot of people who don’t have the realm’s best interests at heart.

2) The heir grows up in a condition of immense power and privilege, so it’s very hard for anyone, even the actual monarch, to stop them from falling into bad habits or just developing an excessive taste for the perks of being part of the royal dynasty.

3) Ultimately, there’s just no guarantee that any of the children of a single person will be that great of a ruler, as compared to the entire talent pool of the entire national population or even the entire aristocracy.

As for North Korea, it’s kind of in a transitional state. Kim Jong Un was clearly the favored contender with a major advantage from being son and grandson of previous rulers, but the Kims haven’t been doing that kind of succession for that long; Kim Il Sun’s death is still well within memory for older members of the elite. Just because your kingdom has a monarchy doesn’t mean there aren’t going to be rivals contending for power from outside the dynasty who want that big royal chair and shiny royal hat for themselves. Hereditary monarchies in a lot of places can’t go more than a few generations without a succession crisis, and in some places they can’t go more than one generation without one (see above).

Jimmy Maher

September 20, 2022 at 7:04 am

Ptolemaic Egypt provides an illustration of how difficult it is to *reliably* create good hereditary monarchs. Ptolemy I, the founder of the dynasty, was steeped in Greek philosophy, and explicitly attempted to mold his regime after Plato’s notion of the “philosopher king.” He went to great pains to steep his son in the same ethic, and it worked; Ptolemy II, like his father, was a pretty good king. Ditto Ptolemy III. But then the lessons failed to take for whatever reason with Ptolemy IV, and the whole house went hopelessly off the rails, degenerating into one of the most notoriously decadent and corrupt in the ancient world. Once a monarchy has lost the plot, it seems, it’s very hard to find it again.

Simon_Jester

October 10, 2022 at 12:56 pm

It’s a good example, with the minor caveat that I normally hesitate to use the word “decadent” to characterize entire societies and dynasties. The term is a bit problematic to define clearly (see

In particular, I get the sense that the characterization of Ptolemaic Egypt as “decadent” has a lot to do with most of our first-tier ‘primary secondary’ sources on its history being Roman. Roman commentary on “the decadent East,” much like Greek commentary on the Persian Empire as “a nation of slaves” or what have you, has to be taken with a grain of salt. When the Romans wrote about Egypt, they were often writing about trends within their own society. Usually trends that the Roman writer didn’t like or approve of, and that they externalized onto (again) “the decadent East.”

Many of these trends spoke to Roman-specific cultural bugbears, such as anxiety about loss of vir, manly power and forcefulness, from exposure to foreign customs like weird music, comfortable clothing, and drinking a lot of wine. Disentangling what actually happened between Antony and Cleopatra, for instance, from what was the product of people spreading rumors about the stalwart Marc Antony being ‘unmanned’ by exposure to a ‘foreign Oriental temptress’…

[rolls eyes]

Well, let’s just say that sorting out the facts of the matter from the cultural overlay is complicated.

But with that said, Ptolemaic Egypt had a whole heap of problems, no matter what terms we use to discuss those problems, and yes, it’s a great illustration of what you’re talking about here.

Ilmari

April 28, 2018 at 6:14 pm

Even if it would seem believable that a biological heir of a good leader would inherit the traits of the predecessor, there are still a bit too many instances of sons (and occasionally daughters) of competent rulers to be just the opposite. My favourite example is the Nervan-Trajan dynasty of Roman emperors. Most persons in this dynasty were remembered as the best emperors in the whole Roman history. The peculiar thing was that the emperors of this dynasty usually selected the most able person among their associates and adopted him, so that the next emperor-to-be was not chosen by biological considerations. This trend was finally broken by Marcus Aurelius, who wanted his son Commodus to be his heir – and Commodus pretty much sucked in the job and was indeed the last emperor of this dynasty.

killias2

August 30, 2021 at 12:17 pm

I know it’s years later, but I try to correct this when I come across it:

Most of the Good Emperors of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty didn’t give the throne to biological sons because they didn’t have any. As a result, they adopted sons to leave the throne to instead. Marcus Aurelius, on the other hand, actually had a biological son, so the overwhelming expectation was that his son would be next in line.

When you realize that the adoption process was fundamental to the succession of the earlier Good Emperors (and other earlier emperors, as well), then you can also realize that the only legitimate form of succession was seen as Father-to-Son.

Simon_Jester

September 20, 2022 at 3:21 am

Quite true, but at the same time, it makes it all the more obvious that father-to-son royal inheritance along biological lines was simultaneously (1) expected and normative to the point where an emperor who had no sons was an instant political crisis unless he adopted, and (2) routinely a disastrous mess for Roman Empire and many other polities that practiced it.

Kevin McHugh

May 10, 2018 at 7:06 pm

Nepotism has not been proven very successful in business (with one exception). If leadership traits were extremely heritable or even highly teachable, businesses that remain led by the same family ought to see continued or even heightened success as successive generations achieve or surpass the same abilities of the founder.

The only time this happens is in Japan, where adult adoption is used to anoint a proven underling as the next head of the company.

Martin

April 27, 2018 at 10:43 pm

not to mention the soldiers in our army, don’t themselves produce good and services

Maybe they produce good and maybe they don’t, but you probably meant “goods”.

Perhaps one benefit of a non-powerful monarch is they they do not need to elect a political head of state. While many can hate a lot about their government, is it better to have a head of state that can be liked by most which seems to be getting harder and harder in 21st century nations?

Jimmy Maher

April 28, 2018 at 6:57 am

Indeed. Thanks!

That is an argument often seen in favor of national-heritage monarchies, and there’s probably something to it. But my egalitarian instincts rather override it — not that I’m hugely exercised about the whole debate. If people want their puppet royals to follow in the tabloids and society pages, and as long as I can equally easily ignore them, fair enough.

Martin

April 28, 2018 at 12:29 pm

This may be the more interesting question. Is there any form of government where power is not centralized in one person? Perhaps the US, three branches of government, is somewhere in that direction but one branch, the executive branch, gets a larger share of the pie than the others.

Jimmy Maher

April 28, 2018 at 2:00 pm

What you’re describing is the difference between the ceremonial head of state and the chief executive. In some countries, such as the vestigial monarchies of Europe, these are separate people; in others, such as the United States, they’re the same. But no, I can’t think of any country that lacks them entirely, with the possible exception of completely failed, essentially government-less “countries” like Somalia.

Eriorg

April 28, 2018 at 2:37 pm

Is there any form of government where power is not centralized in one person?

I don’t know if it’s what you mean, but here in Switzerland, the Federal_Council is the collective head of state, with seven members of equal importance. Admittedly, one of these members (a different one every year) is the President, but it’s very different from Presidents of countries like France or the United States: the Swiss President doesn’t really have more power than the six other members.

Jimmy Maher

April 28, 2018 at 2:52 pm

Interesting. I didn’t know that.

Tom

April 28, 2018 at 1:55 am

“I tend to think the final straw was the abject failure of the European kings and queens, almost all of whom were in family with one another in one way or another, to do anything to stop the slow, tragically pointless march up to World War I.”

Sort of. It wasn’t the fact that they failed to stop World War I that saw their crowns in the gutter. It was the fact that they couldn’t hold their countries together that saw the discrediting of the idea of monarchy.

Simon_Jester

October 10, 2022 at 1:42 pm

Coming back to this much later, it seems to me that several of the major European monarchies were never going to be able to hold their countries together in a protracted war, and should have known it.

Russia was a mess and Nicholas II was a fool who had already done a lot of damage before the war even started. The Ottomans had already lost a lot of territory in the Balkans War and the government had been effectively taken over from the Sultan. Germany was picking a fight with a much larger coalition of powers and likely would have gotten beaten into the ground if not for the ridiculous advantages that the exact technological palette available in 1914 conferred upon the defenders.

Exactly none of those powers should have been fighting a catastrophic continental war at that time against those opponents. And Nicholas II and Wilhelm II in particular had played a large role in setting up their countries as being disproportionately likely to get involved in such a war despite the disadvantages of doing so; if I were scoring their games of Civilization, I’d rate Nicky as being below even Dan Quayle, and Willy not much higher.

Of the major monarchies that fell, the only one I’d give an excuse to would be Austria-Hungary. They had an actual casus belli beyond “we have a grudge from forty years ago” or “we have ambitions to make this land part of our sphere of influence.” And Austria-Hungary’s biggest mistake as a unified WWI-era state was that they might have survived victory but were never going to survive defeat without fragmenting along ethnic lines… And they then wound up in the war with a short list of allies that placed them firmly on the losing side.

judgedeadd

April 28, 2018 at 9:07 am

“a phrase like “communist democracy” rings as an oxymoron to ears brought up in the Western tradition of liberal democracy.”

And, for that matter, for quite a few people brought up on the communist side of the Iron Curtain. There was a joke circulating in communist/socialist (and I know the definitions of these labels are quite muddled) Poland: that the adjective “socialist”—as in “socialist justice”, “socialist democracy”—always turns the attached noun into its exact opposite.

xxx

April 28, 2018 at 4:22 pm

As an aside, you should strongly consider finding a copy of a little-known game called _Hidden Agenda_. It’s the best demonstration of the difficulties with despotism which you point out that Civilization doesn’t address.

You start out as the newly-established leader of a fictional Central American banana republic, and your goal is to survive in office for just three years. It’s excruciatingly hard. Everything you do for one faction angers another, and the morally correct things to do are often politically or economically poisonous. You spend the entire game building a house of cards out of favours and promises which usually collapses in some sort of deposition or death by around year two.

As an object lesson in the problems of governance, I can’t recommend it highly enough. I think I learned more from a week with that game that I did from a year’s worth of social studies in high school.

Alan

May 1, 2018 at 4:08 am

For anyone else looking for the game, a 2017 game of the same name complicates things. Adding “trans fiction systems” (the developers) to searches helps.

(Sadly, “trans” and “agenda” in the same search tends to also find crazy conspiracy theories. :-/ )

doctorcasino

April 28, 2018 at 6:10 pm

A very interesting take. In a sense, the sort of conceptual jankiness of the government system (where they’re not really all things of the same order or scope, and sometimes awkwardly analogize with the real-world meanings of the words) is really a result of trying to find tidy names for a game mechanic that is much more straightforward and playable than these messy real-world ideas would allow. Essentially what you lead me to think is that the “governments” boil down to tiers on a single variable: how developed is the state as an independent functioning entity? More developed = more expensive in resources and potential inertia/corruption, but more possibilities unlocked.

A very clear gaming trade-off – and up to a point it maps onto the real-life concepts. We go from the single despot asserting might makes right, to the dynasty claiming divine support (Egypt and China, among others, would dispute your claim that Europe was some kind of homeland of this idea), to the republic, to the fully bureaucratized 20th century administrative state… quite clean and we can see how they map onto the actual game mechanics. The “later” models are more expensive in various ways but permit a larger and more complex society to function. Unfortunately, just introducing a slider control for the “scale of statehood” would be, perhaps, too abstract and metagovernmental for this game, so they end up with these familiar names that muddle the picture badly. “Republic” seems to want to be something like Rome, but also something like a constitutional monarchy (king of the French, rather than the divinely invested France himself), or maybe an partially-developed democracy (rule by a voting bourgeois class but no universal suffrage/rights, otherwise what would “Democracy” have left to be?)…. and in real life of course, monarchies can have highly developed civil services and legal systems (imperial China again), Communism could look like that or like a decentralized collective of small worker-owned enterprises. Autocracies, as you hint, can be the domain of one mighty conqueror with a chain of loyalties, or be enormous administrative states where the identity of the head of state isn’t as important as the paradigm shared by the ruling decision-makers (contemporary China maybe).

One thing that helps is, again the abstraction/up-to-your-imaginationness of the gigantic time-scale. We know we’re not seeing the rise and all of individual kings or dynasties, but the vague disadvantages of Monarchy stand in for, in the aggregate, the kind of drag on a society that maintaining an unstable and self-interested aristocracy would be in practice. If your monarchic Civ goes into a long slump you’re free to imagine it as partly due to the shoddy leadership of an inept and inbred series of kings, and if you choose a revolution to fix the slump, of course in your mind it’s because the restless citizens of Paris have finally had enough of these syphilitic parasites. Something similar must obtain for religion, going back to your last article; Civ doesn’t model individual churches/denominations/religions as institutions or entities that grow or shrink or have their own power base or economic activity, but it just about kind of works as a mask for a gameplay mechanic where to control unhappiness you invest in Techs A, B and C and Buildings X, Y and Z.

I’m less convinced that the same abstraction works when applied to the economy, which we have to consider here since Communism is in the list. Civ is a narrative of a world without meaningfully different *classes*; there are no concentrations of wealth, no decisions about how the distribution of who wins and loses following a certain policy might affect the macro fortunes and nature of the civilization in question. In the worst reading, capitalism is naturalized because it’s never mentioned, and communism has a mix of negative and not-very-interesting effects on life in your civ. But I just think the designers aren’t really thinking it through, and here I’d repeat some of my comments from a few articles ago: sandbox or no, Civ doesn’t really give you a lot of space to imagine *different* societies, different values they might have – different political economies, to put it briefly. Guns versus butter is about as far as it gets. Throwing “communism” in the list basically acts as a red herring for this other, probably messier game of truly different “civilizations.”. As it stands, it’s a bit like an RPG where you can only roleplay as either lawful good, chaotic neutral, or lawful evil, with no encounters or scenarios that would let you stretch other muscles if you wanted to.

(A small, surely unintentional elision in your opening meditations: you begin by talking about the necessary costs of maintaining an army of civil servants to provide desired services, but then on the ‘con’ side you discuss a common suspicion of the kind of person who seeks power through a political career. But — civil servants aren’t politicians and generally the things we’re paying them for are not glamorous and powerful. They’re teachers, trash collectors, fire fighters, meat inspectors, etc. I’m thrilled to pay taxes for them – beats having to do my own trash-collecting and fire-fighting, and as a good socialist I have to point that my “own” “hard-earned” money is created by the state and its “earning” made possible by infrastructure and laws also created by the state with those tax dollars. Feels like you may be casting about for an “on the other hand” downside and ended up with a mismatch. Maybe what you want is the “well I don’t want my tax dollars going to THAT program/military campaign, but I got outvoted” type of thing?)

Jimmy Maher

April 28, 2018 at 6:36 pm

Well, I did say that the ancient Egyptians invented monarchy. ;)

Just as a cigar is sometimes just a cigar, so is a game mechanic sometimes just a game mechanic. I agree that there’s not a whole lot we can extrapolate about the real world from Civilization’s economy-management model. The real-world system it most resembles is, ironically, the centrally-managed economy of a twentieth-century communist state — but I *don’t* think this is at all the message that Meier and Shelley, good American capitalists both, were trying to send. ;) The one area of economics where the game does have something to say is the value of trade between civilizations, and I will be writing about that in a future article.

In regard to your last parenthetical: although most of the people getting paid through tax dollars are indeed civil servants who perform vital functions, the people setting the tax rate are the politicians, and this is bound to create a certain ambivalence. I believe strongly in the mixed economy with a strong social safety net which we have here in Denmark as the best way anyone has yet found of ordering a society, but that doesn’t mean I don’t grumble when I have to write a huge (figurative) check to the state every year. And, judging from the comic strips and stand-up routines, so do lots of other people who live here. I feel like this is a normal human reaction, the entrepreneurial part of the psyche kicking in and saying, “I worked hard for this, and I want to keep it!” It’s a sign of the tension between the individual and the collective that’s always been at the heart of the debate over government.

Simon_Jester

October 10, 2022 at 2:08 pm

Coming back to this much later, it’s interesting to see how the designers (Meier in particular) modified the system in later games designed around the same core premises.

Civilization II and III follow the same basic template of governments almost exactly; II has ‘Fundamentalism’ as a government choice along with the original six, while III removes it. “Fundamentalism” is interesting as a mechanic because it changes so many core systems of the game that a fundamentalist player is playing an almost completely different game from anyone else- research rates are halved, army support costs drop off enormously, happiness effectively disappears as a game mechanic, and you get “Fanatics,” a special Fundamentalism-only cheap infantry unit that any heavily developed late-game industrial center can churn out at a rate of one per turn. It’s very well suited for beating other civs up and taking their lunch money, and not much else.

Sid Meier’s Alpha Centauri, roughly contemporary with Civ III, has very different “government” mechanics. Which faction/civilization you choose in SMAC actually makes a difference because they all have different strengths and weaknesses, rather than the differences being purely cosmetic. Different government options can further modify (and often exaggerate or mitigate) these initial strengths and weaknesses. And governments are ‘built up’ from a palette of different options; you can run a Planned economy full of cyborgs that values Knowledge and is a Democracy, but you can also run a Planned economy full of cyborgs that values Knowledge and is a Police State. Or you can say “I’ll have the Planned economy, but go easy on the cyborgs,” or keep the cyborgs and Knowledge values but adopt laissez-faire Free Market economics, and so on, and so on.

This mechanic is reprised in Civilization IV, which is a much more significant reimagining of the core game mechanics than we really see in the first, second, or third incarnations of the Civilization series. Playing as the Romans is mechanically different from playing as the Dutch in a variety of ways, and playing as either, you can customize the way your government works to embrace a variety of economic underpinnings, government structures, approaches to army mobilization, and so on. Quite a few of these government choices connect to unique gameplay options. For instance, societies with “Slavery” as their core economic government pick can work city population to death building a project, but no other government choices do that. The spread of major international corporations is a major late-game mechanic and the spread of religions is a major mechanic throughout the game, but the “State Property” and “Atheism” choices in the economic and religious categories effectively shut those mechanics down entirely.

I am less familiar with Civilization V and VI, so I will withhold comment.

Alex Freeman

April 28, 2018 at 7:04 pm

Here are some interesting articles on game theory as applied to politics:

http://www.huppi.com/kangaroo/L-spectrumtwo.htm

http://www.huppi.com/kangaroo/L-spectrumfour.htm

http://www.huppi.com/kangaroo/L-spectrumfive.htm

tedder

April 28, 2018 at 8:36 pm

Oh good, libertarians haven’t found the comment section yet :)

1: Perhaps someone can tell me if there’s a difference between Civ’s despotism and real-world dicatorships?

2: “it’s natural for any father to want to leave a legacy to his son. Why not the country he happens to rule?”

I notice you (intentionally) avoided using your ‘female-first for examples’ preference here :)

3: I never thought about the difference between despotism/dictatorship and monarchy as being the mythology.

4: Gonna take this out of the article’s context and leave it here: “With leadership like that, a country doesn’t need external enemies to eat itself alive.”

Spike

April 29, 2018 at 12:52 am

“Indeed, the royal family of many a country may have wound up ironically less qualified for the job of running it than the average citizen, thanks to a habit of inbreeding in the name of maintaining those precious bloodlines, which could sometimes lead to unusual incidences of birth defects and mental disorders.”

See: Charles II of Spain. :)

“The despot or the monarch for all intents and purposes is the state.”

I was so sure you were about to quote Louis XIV here: “L’Etat, c’est moi.” (Wikiquote does say this is apocryphal. There’s a Civ connection, though: Civ IV uses it as the accompanying quote for the Divine Right technology.)

Lhexa

May 16, 2018 at 8:45 pm

The Republic is not a treatise. -_-

Mike Taylor

November 13, 2018 at 12:29 am

“Each of Civilization‘s broadly-drawn governments provides one set of answers to the eternally fraught questions of who should have power in a society, what the limits of that power should be, and whence the power should be derived.”

I am reliably informed that it derives from a mandate from the masses, not from some farcical aquatic ceremony.

Lisa H.

November 13, 2018 at 3:40 am

If you went round saying you were an emperor…

Mike Taylor

November 13, 2018 at 8:20 am

“Nepotism has not been proven very successful in business (with one exception)”

What’s the exception?

Leo Vellés

April 4, 2020 at 5:50 pm

“how many of us don’t cringe a little when we have to pay the taxman our of our own hard-earned wages?”

A double “our” i think

Leo Vellés

April 4, 2020 at 6:56 pm

Reading it carefully again, now i realized it’s intended

Jimmy Maher

April 5, 2020 at 8:08 am

Actually was a typo. The first “our” should have been “out.” Thanks!

Simon_Jester

September 20, 2022 at 4:37 am

Hm.

I think one area where anthropology and archaeology undermine the picture created by the text of Civilization (and the very similar Civ II) is that it’s very far from obvious that the first governments were “despotisms” in the sense of “pure rule by force on the part of a strongman and his immediate personal goon squad.”

If we look at, for example, the governance of a Greek polis (not just Athens or Sparta but the bitty little ones that are more obscure), we see city-states with power apportioned between various elite councils (moneyed citizens, elders, etc.) and citizen assemblies. Sometimes there was a tyrant or a king, but often not, and even when there was, he was often contending with elite councils, assemblies, or both as independent power centers.

Again and again, all over the world, a more nuanced look at the earliest civilizations and proto-civilizations (e.g. Neolithic tribes in the New Guinea highlands, totally untouched by the outside world before the 1930s, who practiced agriculture but have no settlements larger than a village) indicates more complex power structures that were not so crude and simplistic. There was never a worldwide era of “big man with stick hit you if disobey, make him overlord” being all there was to governance in a civilization.

Steve Pitts

December 24, 2023 at 4:50 pm

“an inherit problem”

Unless this was intended as some sort of play on words then I think you meant ‘inherent’

“the state as an ongoing entity onto itself”

Unto itself, surely?

Jimmy Maher

December 27, 2023 at 2:41 pm

Thanks!

RatherDashing

March 18, 2024 at 4:32 pm

Late to the party on this excellent series, but I did want to point out one amusing note about Civilization and the possibility of being deposed. The first game in the series was actually the only one (as far as I know) to incorporate pretenders questioning your rightful, immortal rule.

It was a form of copy protection. A usurper would question your royal lineage, which you could prove by answering trivia questions relating to specific pages in the physical manual.

I suppose to cultural takeaway is that regardless of government type, your biggest threats are random trivia questions and primitive DRM.