Original-series Star Trek is the only version I’ve ever been able to bring myself to care about. Yet this Star Trek I once cared about a great deal.

Doubtless like many of you of a similar age, I grew up with this 1960s incarnation of the show — the incarnation which its creator Gene Roddenberry so famously pitched to the CBS television network as Wagon Train to the Stars, the one which during my childhood was the only Star Trek extant. Three or four Saturdays per year, a local UHF television station would run a Star Trek marathon, featuring nine or ten episodes back to back, interspersed with interviews and other behind-the-scenes segments. Strange as it now sounds even to me in this era when vintage media far more obscure than Star Trek is instantly accessible at any time, these marathons were major events in my young life. I particularly loved the give and take on the bridge of the starship Enterprise during episodes such as “Balance of Terror,” which were heavily inspired by the naval battles of World War II. Upon realizing this, I became quite the little war monger for a while there, devouring every book and movie I could find on the subject. Even after it had slowly dawned on me that in the final reckoning the death and suffering brought on by war far outweigh any courage or glory it might engender, the fascination with history which had been thus awakened never died.

I loved the Star Trek movies of the 1980s as well. Young though I was, I recognized the poignancy inherent in watching the now middle-aged cast cram their increasingly substantial frames back into the confines of their Starfleet uniforms every couple of years. Yes, this made effortless fodder for the late-night comedians, but there was also a wry wisdom to these movies that one doesn’t usually find in such blockbuster fare, as the actors’ aging off-screen selves merged with their onscreen personas in a way we don’t often see in mainstream mass media. Think, for example, of the scene in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan where McCoy comes to visit Kirk and present him with his first pair of reading glasses. Decades before I fully understood what that moment — not to mention an expanding middle-aged waistline! — means in real life, I could sense the gravitas of the scene. I credit this side of Star Trek with showing me that there is as much drama and interest in ordinary life as there is in fantastic adventures in outer space. It primed me for the evening I begrudgingly opened Ethan Frome for my English class, and proceeded to devour it over the course of the next several rapt, tear-streaked hours. My English teacher was right, I realized; books without any spaceships or dragons in them really could be pretty darn great. Some years later, I took my bachelor’s degree in literature.

It must have been about the time I was discovering Ethan Frome that Star Trek: The Next Generation debuted on television. Like most of my peers, I was hugely excited by the prospect, and tuned in eagerly to the first episode. Yet I was disappointed by what I saw. The new incarnation of the Enterprise seemed cold and antiseptic in comparison to the old ship’s trusty physicality. Nor did I care for the new crew, who struck me as equally bland and bloodless. Being smart enough even at this tender age to recognize that fictional personalities, like real ones, need time to ripen and deepen, I gave the show another chance — repeatedly, over the course of years. But it continued to do nothing for me. Instead of Wagon Train to the Stars, this version struck me as Bureaucrats in Space.

All of this, I’ll freely admit, may have more to do with the fact that The Next Generation came along after I had passed science fiction’s golden age of twelve than anything else. Nevertheless, it does much to explain why I’m the perfect audience for our subject of today: the two Star Trek adventure games which Interplay made in the early 1990s. Throwbacks to the distant past of the franchise even when they were brand new, they continue to stand out from the pack today for their retro sensibilities. Fortunately, these are sensibilities which I unabashedly share.

Star Trek hadn’t been well-served by commercial computer games prior to the 1990s. Corporate nepotism had placed its digital-game rights in the slightly clueless hands of the book publisher Simon & Schuster, which was owned, like the show’s parent studio Paramount Pictures, by the media conglomerate known as Gulf and Western. The result had been a series of games that occasionally flirted with mediocrity but more typically fell short of even that standard. Even as each new Star Trek film topped the box-office charts, and even after Star Trek: The Next Generation became the most successful first-run series in the history of syndicated television, Simon & Schuster’s games somehow managed not to become hits. At decade’s end, Paramount granted the rights to a game based on the film Star Trek V: The Final Frontier to the dedicated computer-game publisher Mindscape, but the end product proved little better than what had come before in terms of quality or commercial success. Still, the switch to Mindscape did show that an inkling of awareness of the money all these half-assed Star Trek games were leaving on the table was dawning at last upon Paramount.

As the new decade began, the silver anniversary of the original series’s first broadcast on September 8, 1966, was beginning to loom large. Paramount decided to celebrate the occasion with something of a media blitz, anchored by a two-hour television special that would air in 1991 as close as possible to the show’s exact 25th anniversary. For the first time on this occasion, Paramount decided to make digital games into a concerted part of their media strategy rather than an afterthought. They signed a contract with the Japanese company Konami to make a game, entitled simply Star Trek: 25th Anniversary, for the Nintendo Entertainment System, the heart of the videogame mass market, and for the Nintendo Gameboy, the hot new handheld videogame system. Rather than the Next Generation crew or even the original Enterprise crew in their most recent, most rotund incarnations, these games were to wind the clock all the way back to those heady early days of 1966, when Captain Kirk was still happy to appear on camera with his shirt off.

That deal still left a space for an anniversary title in the computer-game market. Said market was, it was true, much smaller than the one for Nintendo games, but it was notable for its older, more well-heeled buyers willing to pay more money for more ambitious games. Yet computer-game publishers proved more reluctant to sign on for the project than the broad popularity of the Star Trek brand in general might lead one to believe.

It didn’t require the benefit of hindsight to see that the Star Trek franchise, although it was indeed more popular than ever before, was going through a period of transition in 1990. The Next Generation had been on the air for three seasons now and was heading into a fourth; it was thus about to exceed the on-air longevity of the series that had inspired it. Meanwhile the cast of that older series were bowing to the realities of age at last; it had been announced that Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country, due for release in late 1991, was to be the last feature film in which they would star. A time when the Next Generation crew would become the default face of Star Trek, the original crew creaky anachronisms, was no longer impossible to imagine.

Given this passing of the torch that seemed to be in progress, most computer-game publishers were skeptical of Paramount’s plans for games featuring the original Enterprise and its crew in their youngest incarnations. They felt that this version of Star Trek was already all but dead in commercial terms, what with the success of all of the franchise’s more recent productions.

Brian Fargo of Interplay Entertainment was among the few who didn’t agree with this point of view. He pitched a computer game to Paramount that would share a name with Konami’s efforts, but would otherwise be a completely separate experience. Aided by his natural charm and the relative disinterest of most of Interplay’s competitors, he made the deal.

Disinterested competitors or no, it was quite a coup for his company, nowhere close to the largest or most prominent in its industry, to secure a license to make Star Trek games — especially given that the deal was made just months after Interplay had acquired the rights to another holy totem of nerd culture, The Lord of the Rings. While the Tolkien games would prove rather a disappointment, the Star Trek license would work out better all the way around.

Interplay signed an open-ended contract with Paramount which allowed them to make Star Trek games all the way until the year 2000, with some significant restrictions: they would be subject to the studio’s veto power over any and all of their aspects, and they could be set only in the time of Captain Kirk and company’s first five-year mission. With these restrictions in mind, Interplay set out to make a game that would be slavishly faithful to the original television series’s format. Instead of a single epic adventure, the game would consist of eight independent “episodes,” each roughly equivalent in plot complexity and geographic scope to those that had aired on television back in the day.

The structure of each episode would be the same: the Enterprise would be called upon by Starfleet to handle some new crisis at the episode’s beginning, whereupon the player would have to warp to the correct star system and engage in some action-oriented space combat, before beaming down to the real heart of the problem and sorting it all out in the guise of an adventure game. Interplay noted that the episodic format could make for a refreshing change from the norm in adventure games, being amenable to a more casual approach. Each episode would be designed to be completable in an evening; after finishing one of them, you could start on the episode that followed the next day, the next week, or the next month, without having to worry about all of the plot and puzzle threads you left dangling last time you played. From Fargo’s perspective, the episodic structure also had the advantage that each part of the game could be designed without much reference to or dependence on any of the others; this made things vastly easier from the standpoint of project management.

Fargo turned to a familiar source for the episodes’ scripts: Michael Stackpole, a member of the Arizona Flying Buffalo fraternity who had played a leading role on Interplay’s Wasteland CRPG and contributed to such other titles as Neuromancer. Stackpole had been busying himself recently with writing tie-in novels set in the universe of the BattleTech tabletop-game franchise. He thus thought that he knew what to expect from working with a licensed property, but he was unprepared for the degree of micromanagement that a bureaucratic giant like Paramount, stewarding one of the most valuable media properties of the age, was willing to engage in. He submitted scripts for fifteen episodes for a game that was anticipated to contain only eight, assuming that should surely cover all his bases; Interplay and Paramount could decide between themselves which eight they actually wanted to include.

To everyone’s shock, Paramount outright rejected all but a handful of them weeks later, usually for the most persnickety of reasons. Interplay’s frustration was still evident in a preview of the game published much later in Computer Gaming World magazine, which noted that “the film studio decided against plot elements derived from episodes which were already part of the Star Trek legend.” With Stackpole having returned to writing his novels, Fargo brought in Elizabeth Danforth, another Flying Buffalo alumnus who had worked with Interplay before, to write more episodes and shepherd them through the labyrinthine approval process.

All of this was happening during one of the most chaotic periods in Interplay’s history. Their distributor Mediagenic had just collapsed, defaulting on hundreds of thousands of dollars they had owed to Interplay and destroying the company’s precious pipeline to retail. The Lord of the Rings game, which was supposed to have been their savior, missed the Christmas 1990 buying season and, when it did finally ship early the following year, met with lukewarm reviews and disappointing sales. Only the strategy game Castles, an out-of-left-field hit from a third-party developer, kept them alive.

Amidst it all, the team making Star Trek: 25th Anniversary kept plugging away — but, inevitably, the game fell behind schedule. September of 1991 arrived, bringing with it the big television special and the Nintendo Entertainment System game, but Interplay’s own tie-in product remained far from complete. It didn’t ship until March of 1992, by which time all of the anniversary hoopla was in the past. Interplay’s game had all the trappings of an anticlimax; it really should have been known as Star Trek: 26th Anniversary, noted more than one commentator pointedly. For those inside the company, the story of the game was taking on some worrisome parallels to that of their Lord of the Rings title: a seeming surefire hit of a high-profile licensed game that arrived late and wound up underwhelming everyone.

They needn’t have worried. Star Trek: 25th Anniversary was a much more polished, more fully realized evocation of its source material than The Lord of the Rings had been, and it came at one of the Star Trek franchise’s high-water marks in popularity. Star Trek VI, which had hit theaters just three months before Interplay’s game, had become everything one could have hoped for from the original crew’s valedictory lap, garnering generally stellar reviews and impressive box-office receipts. Meanwhile The Next Generation was now in its fifth season on television and more popular than ever. The only shadow over proceedings was the death of Gene Roddenberry, the creator of Star Trek, on October 24, 1991. Yet even that event was more help than hindrance to the Interplay game’s commercial prospects, in that it created an appetite among wistful fans to look back to the franchise’s beginnings.

Indeed, Star Trek: 25th Anniversary thrived in this febrile atmosphere of contemporary success tinged with nostalgia. It became the biggest Interplay hit since Battle Chess, selling over 250,000 copies in all and doing much to set the company’s feet back on firm financial ground after the chaos of the previous couple of years.

The game continues to stand up fairly well today, with a few caveats. Undoubtedly its least satisfying aspect is the space-combat sequence that must be endured at the beginning of each episode. Perhaps not coincidentally, this is one of the few places where the game isn’t faithful to the spirit of Star Trek.

Science fiction’s two most successful media franchises take very different approaches to battles in outer space: while Star Trek portrays its combatants as lumbering naval vessels, jockeying for position in a slow-paced tactical game of cat and mouse, Star Wars looks to the skies of World War II for inspiration, opting for frenetic dog fights in space. But 25th Anniversary goes all-in for Star Wars instead of Star Trek in this respect; the Enterprise turns into Luke Skywalker’s X-Wing fighter, dodging and weaving and spinning on a dime in response to the joystick. The reason for the switch can be summed up in two words: Wing Commander. Origin Systems’s cinematic action game of outer-space dog-fighting was taking the market by storm as Interplay was starting work on their own science-fiction game, and the company wanted to capitalize on their rival’s success. They described their game as “Sierra meets Wing Commander” at early trade-show presentations, and even made it possible to engage in randomized fights just for fun by visiting star systems other than those to which you’ve been directed, just in case the fighting you get to do in the episodes proper isn’t enough for you.

That was quite the stretch; the combat in 25th Anniversary really isn’t much fun as anything more than an occasional palate cleanser, and it’s hard to imagine anyone voluntarily deciding to look for more of it. Not only does this part of the game clash with its faithfulness to Star Trek in just about every other respect, but it doesn’t work even on its own terms. The controls are awkward, it’s hard to understand where your enemies are in relation to you, and it’s simply too hard — a point I’ll be returning to later. For now, suffice to say that Star Trek: 25th Anniversary ain’t no Wing Commander.

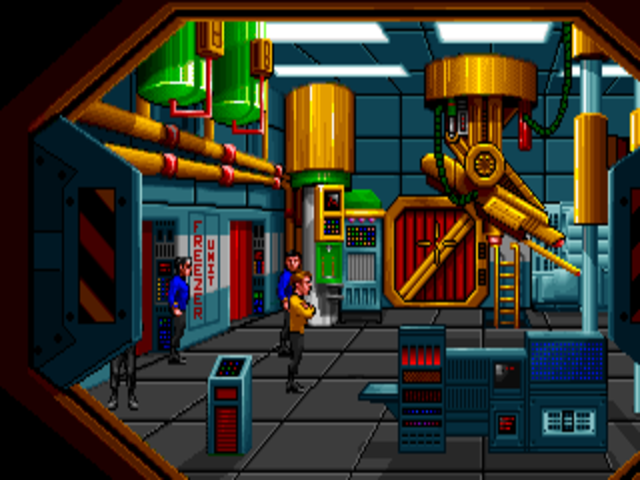

Thankfully, the rest of the game — the “Sierra” in Interplay’s pithy formulation — is both more engaging and more faithful to the Star Trek of old. When you leave the Enterprise‘s bridge, the game turns into a point-and-click graphic adventure, marking the first time Interplay had dabbled in the format since Tass Times in Tonetown back in 1986. You control Kirk directly, but Spock, McCoy, and some poor expendable redshirt also come along, ready to offer their advice and use their special talents when needed — or, in the case of the redshirt, to take one for the team, dying so that none of the regulars have to do so.

The interface can be a little confusing at first; it’s not always clear when you should be “using” Spock or McCoy themselves on something and when you should be using their tricorders. But you start to get a feel for things after just a few minutes, and soon the interface fades into the background of what could stand on its own as a solid little graphic adventure — or, rather, eight solid little mini-adventures. Some of the puzzles can get a bit fiddly, but there are no outrageously unfair ones. The episodic nature of the game does much to make it manageable by limiting the possibility space you need to explore in order to solve any given puzzle; most of the episodes play out over just half a dozen or so locations.

Still, what elevates a fairly workmanlike adventure game to something far more memorable is the Star Trek connection. This is clearly a game made by and for fans of the source material. If you count yourself among them, you almost can’t help but be delighted. The writers do a great job of evoking the characters we know and love; McCoy lays into Spock like the old racist country doctor he is, Spock plays such a perfect straight man that one can’t help but suspect that he’s laughing up his sleeve behind his facade of “logic,” and Kirk still loves to egg them both on and enjoy the fireworks.

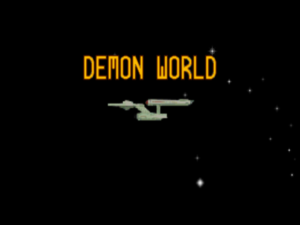

Star Trek: 25th Anniversary apes the look of its source material down to the title card that opens each episode.

The interactive episodes are true to the rhythms of their non-interactive antecedents; each one begins with a title card superimposed over a stately Enterprise soaring toward its latest adventure, and ends with some humorous banter on the bridge and a final command from Kirk of “Warp factor 4!” to send it on its way to the next. Even the visuals, presented in slightly pixelated low-res VGA, conjure up the low-rent sets of the show; more photo-realistic graphics, one suspects, would only ruin the effect. For the music, George “The Fat Man” Sanger and Dave Govett, whose work was everywhere during this period — they scored Wing Commander and Ultima Underworld as well, among many others — mix the familiar Star Trek theme with their own period-perfect motifs. The only things missing from their score in comparison to that of the original show are those oh-so-sixties orchestral stabs at dramatic moments. (There does come a point, Sanger and Govett must have decided, when nostalgia descends into outright cheese.)

It’s true that the episodes work more on the level of pastiche than that of earnest attempts at storytelling — another reason that enjoying this game probably does require you be a fan of vintage Star Trek. Most of the scripts read like a Mad Libs take on the original series, mixing and matching its most familiar tropes. The crew has to shut down another misguided computer (à la “A Taste of Armageddon”), engage in some gunboat diplomacy with the Romulans (“The Enterprise Incident”), and negotiate an earthly religious mythos transplanted to another planet (“Who Mourns for Adonais?”). Harry Mudd, the intergalactic con man whose antics featured in two episodes of the original series, makes a third appearance here. Even Carol Marcus, scientist and Kirk paramour, shows up to foreshadow the major role she’ll later play in the movie Star Trek II.

Star Trek: 25th Anniversary in its graphic-adventure mode. The gang’s all here, including the poor terrified redshirt hiding behind a pillar.

If none of the interactive episodes can challenge the likes of “The City on the Edge of Forever” for the crown of Best of Trek, they’re certainly far less embarrassing than most of what the series produced during its painfully bad third season. They encompass the full tonal palette of the show, from screwball comedy to philosophical profundity. The graphic-adventure format does force a shift in emphasis away from dialog and action to more cerebral activities — the Kirk on television never had to slow down to solve set-piece logic puzzles like some of the ones we see here — but that shift is entirely understandable.

Unfortunately, all of the good will the game engenders is undermined to a considerable extent by one resoundingly terrible design decision — a decision that’s ironically built upon a foundation of very good design choices. Each episode permits multiple solutions to most of the problems it places before you; this is, of course, a good thing. At the end of each episode, assuming you don’t get yourself killed, you receive an evaluation from Starfleet Command in the form of a percentile grade. You’re rewarded with a better grade if you’ve managed to keep the poor redshirt who beamed down with you alive — this game’s writers show far more compassion for the expendable crew members than the original series’s writers ever did! — and if you’ve accomplished things with a minimum of violence — i.e., if you’ve kept your metaphorical and sometimes literal phasers on “stun” rather than “kill.” All of this too is a good thing, seeming evidence of a progressive design sensibility that’s become ubiquitous today, when countless games let you finish each scenario with a bronze, silver, or gold star, allowing you to be exactly as completionist and perfectionist as you choose to be.

But now the bad part comes in. The final grades you receive on the episodes affect the performance of your crew during the remaining space-combat sequences, which themselves become steadily more difficult as you progress through the game. In fact, the final battle is so hard that you virtually have to have scored 100 percent on all of the preceding episodes to even have a chance in it. It turns out that the seeming easygoing attitude of the game, encouraging you to do better but letting you slide if you just want to move on through the episodes, has been a colossal lie, an ugly trap to get you 90 percent of the way to the finish line and then stop you cold. This is like a caricature of awful, retrograde game design — something even Sierra at their absolute nadir would have thought twice about. Either tell the player at the end of the episode that she just hasn’t done well enough and make her do it again, or honor your promise to let her continue with a less than stellar score. Don’t lie to her about it and then cackle about how you got her in the end.

Not only is this design decision terrible on its own terms, but it clashes with all of the implications of Interplay’s own characterization of Star Trek: 25th Anniversary as a more casual sort of adventure game than the norm, one that will let you play through a satisfying episode in a single relaxing evening. Interplay heard about this cognitive dissonance from their fans — heard so much about it that they begrudgingly issued an optional patch that let players skip past the combat sequences altogether by triggering a hot key. It wasn’t the most elegant solution, but it was better than nothing.

This discordant note aside, the worst complaint you could make about Star Trek: 25th Anniversary in 1992 is one that doesn’t apply anymore today: that it was just a bit short in light of its $40 street price. And yet, worthy effort though Interplay’s first Star Trek game is on the whole, they would comprehensively top it with their second.

Given 25th Anniversary‘s commercial success and the open-ended license Interplay had acquired from Paramount, a sequel was rather inevitable. There wasn’t much point in making bold changes to a formula that had worked so well. Indeed, when they made the sequel they elected to change nothing whatsoever on the surface, retaining the same engine, the same episodic structure, and even the same little-loved combat sequences. Yet when we peer beneath the surface we see the product of a development team willing to learn from their mistakes. As sometimes happens in game development, the fact that the necessary enabling technology was already in place in the form of an existing engine allowed design in the abstract to come even more to the fore in the sequel. The end result is a game that, while hardly a transformative leap over its predecessor, is less frustrating, more narratively ambitious, and even more fun to play.

Although Star Trek: Judgment Rites continues with the episodic structure of its predecessor, it adapts it to a format more typical of television shows of the 1990s than those of the 1960s. An overarching “season-long” story arc is woven through the otherwise discrete episodes, to come to a head in a big finale episode. This gives the game a feeling of unity that its predecessor lacks.

Even more welcome, however, is a new willingness within the individual episodes to move beyond pastiche and into some narratively intriguing spaces of their own. Virtually all of Judgment Rites‘s episodes, written this time by the in-house Interplay employees Scott Bennie and Mark O’Green in addition to the returning contractors Michael Stackpole and Elizabeth Danforth, mix things up rather than stick with the unbending 25th Anniversary formula of a space combat followed by Kirk, Spock, McCoy, and a semi-anonymous redshirt beaming down somewhere. Combat this time around is neither as frequent nor as predictably placed in the episodes, and the teams that beam down now vary considerably; Scotty, Uhura, and Sulu all get at least one chance of their own to come along and use their special talents.

My favorite episode in Judgment Rites also happens to be the longest and most complex in either of the games. In Bennie’s “No Man’s Land,” a team from the Enterprise beams down to a planet which is being forced to reenact a simulacrum of Earth’s World War I by Trelane, the childish but almost infinitely powerful demigod who was introduced in the original-series episode “The Squire of Gothos.” As his inclusion would indicate, “No Man’s Land” is very aware of Star Trek lore. It’s plainly meant partially as an homage to the original show’s occasional “time-travel” episodes, like “Tomorrow is Yesterday,” “A Piece of the Action,” or “Patterns of Force.” These were beloved by fans for giving the familiar crew the chance to act out a bit in an entirely different milieu. (They were beloved by the show’s perpetually cash-strapped producers for another reason: they let them raid their studio’s stash of stock sets, props, and costumes.)

Yet “No Man’s Land” transcends homage to become a surprisingly moving meditation on the tragedy of a pointless war.

Another standout is Stackpole’s “Light and Darkness,” a pointed allegory about the folly of eugenics.

In addition to showing far more confidence in its storytelling, Judgment Rites also addresses the extreme difficulty of the space-combat sequences in its predecessor and the false promise that is letting you continue after completing an episode with a less-than-perfect score. You now have a choice between no combat at all, easy combat, and hard combat. The middle setting is calibrated just about right. Combat at this level, while still a long way from the likes of Wing Commander, becomes an occasional amusing diversion that doesn’t overstay its welcome instead of an infuriating brick wall that kills the rhythm of the game. And, at this level, moving on from any given episode with a score of less than 100 percent is no longer a fool’s gambit.

Although a better game than its predecessor in almost every respect, Judgment Rites couldn’t muster the same sales. It didn’t ship until December of 1993 — i.e., almost two full years after 25th Anniversary — and by that time the engine was beginning to show its age. Nor did it help that Interplay themselves undercut its launch by releasing a “talkie” version of the first game on CD-ROM just a month later.

That said, it’s not hard to understand Interplay’s eagerness to get the talkie version onto the market. In what can only be described as another major coup, Interplay, working through Paramount, brought in the entirety of the original cast to voice their iconic roles. At a time when many CD-ROM-based games were still being voiced by their programmers, it promised to be quite a thrill indeed to listen to the likes of William Shatner, Leonard Nimoy, and Deforest Kelley in the roles that had made them famous.

The reality was perhaps a little less compelling than the promise. While no one would ever accuse any member of the show’s cast of being a master thespian in the abstract, they had been playing these roles for so long that doing so once more for a computer game ought to have presented little problem on the face of it. Yet they plainly struggled with this unfamiliar medium. Their voice acting runs the gamut from bored to confused, but almost always sounds like exactly what it is: actors in front of microphones reading lines on a page. It seems that none of them knew anything about the stories to which the lines related, which can only be construed as a failure on Interplay’s part — albeit one perhaps precipitated by the sharply limited amount of time during which they had the actors at their disposal. Over the course of a scant few days, the cast was asked to voice all of the dialog not for one but for two complete games; the voices for a CD-ROM version of Judgment Rites were recorded at the same time. And they had to do it all bereft of any dramatic context whatsoever.

Somewhat disappointing though the final result is, these sessions represent a melancholy milestone of their own in Trek history, marking the last time the entire cast to the original show was assembled for a new creative project. As such, the talkie versions of these games are the last gasps of an era.

Personally, though, I prefer the games without voices — not only because of the disappointing voice work but because Interplay chose to implement it in a really annoying way, with Kirk/Shatner saying each choice in every dialog menu before you choose one. Interplay, like most of their peers, was still scrambling to figure out what did and didn’t work in this new age of multimedia computing.

Despite holding a license to the original series for the balance of the decade, Interplay would never release another game set in this era of Star Trek after the talkie version of Judgment Rites shipped in March of 1994. The company did work intermittently on an ambitious 3D action-adventure featuring Kirk and the rest of the classic crew, tentatively entitled Secret of Vulcan Fury, near the end of the decade, but never came close to finishing it. Gamers and Trekkies were moving on, and the newer incarnations of the show were becoming, just as some had predicted they would, the default face of the franchise. Indeed, no standalone Star Trek game since the two Interplay titles discussed in this article has revisited the original show. This fact only makes 25th Anniversary and especially Judgment Rites all the more special today.

That would make for a good conclusion to this article, but we do have one more thing to cover — for no article about Interplay’s takes on classic Trek could be complete without the media meme they spawned.

Like a fair number of other memes, this one involves William Shatner, for more than half a century now one of the odder — and more oddly endearing — characters on the media landscape. Back when he was a struggling young actor trying to make it in Hollywood, it was apparently drilled into him by his agents that he should never, ever turn down paying work of any kind. He has continued to live by this maxim to this day. Shatner will do absolutely anything if you pay him enough: pitch any product, sing-talk his way through fascinatingly terrible albums, “write” a new memoir every couple of years along with some of the worst science-fiction novels in history. He’s the ultimate cultural leveler, seeing no distinction between a featured role in a prestigious legal drama and one in a lowest-common-denominator sitcom based on someone’s Twitter feed.

And yet he manages to stay in the public’s good graces by doing it all with a wink and a nod that lets us know he’s in on the joke; when he goes on a talk show to plug his latest book, he can’t even be bothered to seriously pretend that he actually wrote it. He’s elevated crass commercialism to a sort of postmodern performance art. When the stars align, the kitschy becomes profound, and the terrible becomes wonderful. (“Why is this good?” writes a YouTube commenter in response to his even-better-than-the-original version of “Common People.” “It has no right to be this good.”) For this reason, as well as because he’s really, truly funny — one might say that he’s a far better comedian than he ever was an actor — he gets a pass on everything. At age 88 as of this writing, he remains the hippest octogenarian this side of Willie Nelson.

In keeping with his anything-for-a-buck career philosophy, Shatner is seldom eager to spend much time second-guessing — much less redoing — any of his performances. His reputation among media insiders as a prickly character with a taste for humiliation has long preceded him. It’s especially dangerous for anyone he perceives as below him on the totem pole to dare to correct him, challenge him, or just voice an opinion to him. Like a dog, he can smell insecurity, and, his eagerness to move on to the next gig notwithstanding, he’s taken a malicious delight in tormenting many a young assistant director. Craig Duman, the Interplay sound engineer who was given the task of recording Shatner’s lines for the CD-ROM versions of 25th Anniversary and Judgment Rites, can testify to this firsthand.

The problem began when Shatner was voicing the script for the first episode of Judgment Rites. Coming to the line, “Spock, sabotage the system,” he pronounced the word “sabotage” rather, shall we say, idiosyncratically: pronouncing the vowel of the last syllable like “bad” rather than “bod.” A timid-sounding Duman, all too obviously overawed to be in the same room as Captain Kirk, piped up to ask him to say the line again with the correct pronunciation — whereupon Shatner went off. “I don’t say sabotahge! You say sabotahge! I say sabotage!” (You say “potato,” I say “potahto?”) His concluding remark was deliciously divaish: “Please don’t tell me how to act. It sickens me.”

This incident would have remained an in-joke around Interplay’s offices had not an unknown employee from the sound studio they used leaked it to the worst possible person: morning-radio shock jock Howard Stern. Driving to work one morning, Brian Fargo was horrified to hear the outtake being broadcast across the country by this self-proclaimed “King of All Media.” Absent the “it sickens me,” the clip wouldn’t have had much going for it, but with it it was absolutely hilarious; Stern played it over and over again. Fargo was certain he had just witnessed the death of one of Interplay’s most important current projects.

He was lucky; it seems that Shatner wasn’t a regular Howard Stern listener, and didn’t hear about the leak until after both of the talkies had shipped. But the clip, being short enough to encapsulate in a sound file manageable even over a dial-up connection, became one of the most popular memes on the young World Wide Web. It also found a receptive audience within Hollywood, where plenty of people had had similar run-ins with Shatner’s prickly off-camera personality. It finally made its way into the 1999 comedy film Mystery Men, where Ben Stiller parrots, “Please don’t tell me how to act. It sickens me,” on one occasion, and Janeane Garofalo later inserts a pointed, “You say sabotahge! I say sabotage!”

Thanks to Howard Stern, Mystery Men, and the mimetic magic of the Internet, this William Shatner outtake has reached a couple of orders of magnitude more people than ever played the game which spawned it; most of those who have engaged with the meme have no idea of its source. If it seems unfair that this of all things should be the most enduring legacy of Interplay’s loving re-creations of the Star Trek of yore, well, such is life in a world of postmodern media. As Shatner himself would attest, just reaching people, no matter how you have to do it, is an achievement of its own. And if you can make them laugh while you’re about it, so much the better.

(Sources: Computer Gaming World of December 1991, May 1992, March 1994, and May 1994; Questbusters of April 1992; Origin Systems’s internal newsletter Point of Origin of December 9 1991; the special video features included with the Star Trek: Judgment Rites Collector’s Edition. Online sources include Matt Barton’s interview with Brian Fargo and Fargo’s appearance on Angry Centaur Gaming’s International Podcast. Finally, some of this article is drawn from the collection of documents that Brian Fargo donated to the Strong Museum of Play.

Star Trek: 25th Anniversary and Judgment Rites are both available for purchase from GOG.com.)

Ben

April 5, 2019 at 4:37 pm

I’ve been looking forward to this one! Fun game but those combat sequences are absolutely awful.

I’m assuming you didn’t plan it this way, but today is a special day on the Trekkie calendar – it’s the future anniversary of first contact (4/5/2063). How fortuitous.

Sig

April 5, 2019 at 4:57 pm

I adored the first game, and was apparently oblivious to the terrible voice acting because my fond memories are of the full talkie version. Fond memories.

I thought I was just terrible at the space combat; it didn’t occur to me at that age that there might be a game design flaw.

Sniffnoy

April 5, 2019 at 6:03 pm

Quick editing notes: “palette cleanser” should be “palate cleanser”; the “Tass Times in Tonetown” link should likely link to your own article where you discuss it; and the “goes on a talk show” link seems to be malformed.

Jimmy Maher

April 5, 2019 at 8:11 pm

Thanks! I actually linked to the article in question earlier in this one, which is why I sent the Tass Times link straight to MobyGames.

Damian Glenny

April 17, 2019 at 12:06 am

I cannot believe you didn’t reply to this with “please don’t tell me how to write”.

Alex Smith

April 5, 2019 at 8:02 pm

“Star Trek hadn’t been well-served by computer games prior to the 1990s.”

This is no doubt true when we are talking about officially licensed product, but this evaluation ignores the long and highly successful run of tactical combat Star Trek games that proliferated across every timesharing mainframe and microcomputer platform in the 1970s and early 1980s. You could certainly argue that a Star Trek game that consists of nothing but combat ignores most of what made Star Trek great, but commanding the USS Enterprise against hordes of Klingon Battlecruisers was a formative computer gaming experience for many people.

Jimmy Maher

April 5, 2019 at 8:14 pm

Yeah, I talked about that lineage briefly in my article on the Simon & Schuster era of Star Trek games. They do strike me as pretty non-Trekkie in spirit, but I added the qualifier of “commercial.” Thanks!

Ross

April 5, 2019 at 10:33 pm

I’d note that, for example, until I discovered EGATrek in the mid ’90s, my personal favorite of the all-basically-the-same tactical space combat star trek simulators was one that had had all the Star Trek Branding carefully removed for legal reasons.

Gnoman

April 5, 2019 at 10:48 pm

“To everyone’s shock, Paramount outright rejected all but a handful of them weeks later, usually for the most persnickety of reasons.”

This wasn’t unusual for Paramount in that era, and extended even to the then-current show. The material Paramount rejected (or reworked into terrible Wesley episodes) was better than a lot of what they put on the screen in the early seasons of TNG.

Jimmy Maher

April 6, 2019 at 6:51 am

I’ve heard that Gene Roddenberry was actually a big part of the problem with The Next Generation’s early seasons. His creative instincts could be really, really bad. (Witness the turgid lump of would-be profundity that was Star Trek: The Motion Picture, and how much better the movies got after he was sidelined.) But I’m obviously not all that invested in any Star Trek after the original series, so I’ve never delved into the topic in detail.

Gnoman

April 6, 2019 at 11:46 pm

That’s pretty accurate. Roddenberry had some really strange ideas (at one point, he envisioned Kirk and the rest as the last stubborn holdouts to individuality, with the rest of humanity being a single hive mind – in other words, his utopian view of the future was humanity turning into the Borg), and many of the problems in early TNG can be traced to one or another of his policies.

It is no coincidence that most of the finer TNG episodes (“The Drumhead” and “Measure of A Man” in particular stand out as deeply philosophical episodes he would have vetoed) came after he was kicked upstairs.

stepped pyramids

April 8, 2019 at 3:35 pm

“Measure of a Man” was in the second season, when Roddenberry still had some degree of control over the series. The writer, Melissa Snodgrass, says Gene nearly shot down the episode because he believed there would be no lawyers in the 24th century.

Gnoman

April 10, 2019 at 11:11 pm

They were already easing him out at that point (the rebellion started late in season 1), and his control was very weakened. The reasons that he nearly shot down one of the series’s finest episodes for are sort of the reason why the first season and much of the second was so lifeless.

Now that I think about it, there are a lot of similarities between Roddenberry and Steve Jobs.

Aula

April 11, 2019 at 10:15 am

The second season of TNG was significantly affected by the Writers’ Guild strike that was going on at the time (S2 had fewer episodes than any other, the scripts of several episodes were originally written for the Star Trek II series that never happened, and one episode was almost completely recycled footage from various earlier episodes). It’s not quite fair to blame Roddenberry for *every* flaw of S2.

ATMachine

April 6, 2019 at 4:56 am

Small nitpick: that screenshot of “what’s not good enough” is from Judgment Rites rather than 25th Anniversary, the game actually being critiqued at that point.

Jimmy Maher

April 6, 2019 at 6:47 am

Woops. Thanks!

Laertes

April 6, 2019 at 12:05 pm

Reading glasses are unavoidable but, fortunately, not the expanding waistline. Though it takes some effort to keep it in check.

Steve McCrea

April 6, 2019 at 4:51 pm

I don’t hear anything egregious about Shatner’s pronunciation of sabotage. If anything it sounds better than the voice director’s pronunciation. Perhaps it’s a regional thing (Shatner is Canadian, I’m Northern Irish). The voice director was likely not very experienced – and might have gotten better performances if he had been.

stepped pyramids

April 6, 2019 at 10:03 pm

The word is a recent (early 20th century) borrowing from French, and I can’t find any resource that lists it using a different vowel than ɑ. Same vowel as mirage, corsage, etc.

Practically nobody was an experienced video game voice director in 1993. This was the same year that the CD-ROM version of King’s Quest VI came out, which really started the trend of games being voiced by professional casts. It took a while before other game companies started treating voice acting as something other than unusually elaborate sound effects. This being a case in point — the “director” here was an audio engineer and sound designer.

I doubt Shatner was interested in being directed in any case.

Gilles Duchesne

June 1, 2019 at 4:55 am

“The word is a recent (early 20th century) borrowing from French, and I can’t find any resource that lists it using a different vowel than ɑ. Same vowel as mirage, corsage, etc.”

Indeed, *all* those words are similarly mispronounced by English-speaking folks, as far as my French-Canadian-self hears it. Re-writing those words in French, it seems you keep saying sabotâge, mirâge, corsâge. Shatner does say the word as a French-speaking Montrealer would.

Laertes

April 7, 2019 at 5:39 am

I don’t hear anything strange either but I am spanish so how do I know how to pronounce it? I don’t.

Brian

April 6, 2019 at 11:46 pm

Those were the same years that produced Rescue, a gem of the Mac shareware world. It was also combat heavy, in the spirit of late TNG. No scripted episodes, just a sandbox of algebraic missions in the neutral zone.

Nate

April 7, 2019 at 4:25 am

Fun history. I didn’t know about that Mystery Men reference. I’ll have to watch it again.

“You see potato, I say potahto”

Do you mean “say” in the first case?

Jimmy Maher

April 7, 2019 at 6:35 am

Indeed. Thanks!

Jeremy Reimer`

April 7, 2019 at 4:48 am

I loved the first 25th Anniversary game, and as a huge fan of Wing Commander I neither hated the ship combat nor found it too difficult– except of course for that final mission! To this day I had no idea that the difficulty level scaled inversely with your mission rating scores. I will say that it is *possible* to win the final battle without having a full 100% on each mission, because I remember doing it. But it was stupidly hard.

For some reason I never played the sequel, and finding out that it’s available on GoG just made my day! I get to enjoy it for the first time!

Jimmy Maher

April 8, 2019 at 11:41 am

You’re in for a treat! Judgment Rites really is a better game in virtually every respect, so if you liked the first one…

Boris Schneider-Johne

April 7, 2019 at 9:21 am

Jimmy, didn’t Interplay work on a third Star Trek game (Vulcan Fury?), that would have been 3D rendered animations? It was highly ambitious and of course way too big to ever get finished.

Jimmy Maher

April 7, 2019 at 10:09 am

Yes, that did deserve a mention, didn’t it? Duly added. Thanks!

Chris Chapman

April 7, 2019 at 4:34 pm

I spent about ten months on a Secret of Vulcan Fury history video a few years ago, reaching out to all the former team members I could locate to try to find out how much work was done, whether any of it still exists, and the reasons behind the failure of the project. It’s a niche subject within a niche subject — I don’t think anyone else has ever tried to research it specifically — but it may be of interest. I was surprised by what I found; there was much more surviving footage than had been publicly seen.

Not sure about the rules on self-promotion here, so I won’t link to it, but you can find it on YouTube.

Jeremy Reimer

April 7, 2019 at 8:31 pm

Chris, that video was fantastic! Thanks for making it!

Captain Kal

April 9, 2019 at 7:04 pm

Great Video, Chris!! I really liked it!!

Sung J. Woo

April 7, 2019 at 4:57 pm

Hello Jimmy — thank you for all the great work you do. Just a minor quibble — it’s Starfleet, one word:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Starfleet

I’m currently on ebook 1984 and loving every sentence. It makes me very happy to know that there’s another seven years and change to go. You rock, sir, pure and simple.

– Sung

Jimmy Maher

April 7, 2019 at 11:25 pm

Thanks for the correction, thanks for the kind words, and thank you so much for your generous Patreon support!

Bruce Schlickbernd

April 7, 2019 at 7:26 pm

If the author is curious about design decisions about the game, my recommendations would be to interview Jay Patel (lead programmer, designer) and Bruce Schlickbernd (Producer, designer), who put more hours into the game than anyone else, and seem curiously omitted from the article. The author makes some wrong assumptions, some inciteful moments, and even finds some things I didn’t know (Fargo could be secretive on occasion), but generally got things right.

Jacob Bauer

April 8, 2019 at 6:15 am

Jeremy Reimer is right, it is actually possible to win the final mission without 100%. The trick is to set your ship speed so that you are flying backwards. For me, this made the final battle go from impossible to almost easy. I managed to finish the game with one of the lowest possible scores.

ShadowAngel

April 8, 2019 at 5:36 pm

“conjure up the low-rent sets” – It’s sad that Star Trek has this “low budget” stigma, when in reality back then it was one of the most expensive shows put on TV and one only has to compare contemporary shows like Lost in Space to see the difference. From the set pieces to the special effects, Star Trek was anything but “low-rent”

Sure it doesn’t hold up to todays CGI-infested “make everything look as fake and plastic as possible” kind of style but considering it was made over 50 years ago, for TV, to call it low-rent is a big insult. The Special Effects were even groundbreaking for its time, like the episode The Corbomite Maneuver. Desilu employed 4 different Special Effects studios in Hollywood to get Star Trek done.

The average budget per episode for Season 1 was around 190,000 dollars, in Season 2 it was 187,500 to 192,000 dollars and Season 3 dropped to around 178,000. Which still was way higher than the 120,000 for the contemporary Outer Limits, Lost in Space (180,000-140,000) as mentioned and only slightly below the usualy budget of later sci-fi shows, like Space:1999 that was produced from 1975 on with a episode budget of 200,000 dollars per episode.

The two pilots costed even more: 700,000 for The Cage and 500,000 for Where no man has gone beofe

Adamantyr

April 10, 2019 at 3:16 pm

I played a demo version of this game back in the day, but I never got past the first combat.

So the game ALWAYS threw you into combat right off? I would dutifully study the star map and pick the right star and the game would tell me I was “in violation of treaty” and either in Romulan or Klingon space. So naturally I thought I had done something wrong. I systematically tried every star system and finally concluded in frustration the game was broken.

Boot

April 11, 2019 at 4:09 am

“Even after it had slowly dawned on me that in the final reckoning the death and suffering brought on by war far outweigh any courage or glory it might engender”

Woefully misguided. The US is currently remaking the Middle East with war after war. When it’s all done and the borders have been re-adjusted to eliminate the mistakes of European colonialists, all wars there will cease. Forever.

Without the USA’s muscular hegemony to accomplish this historical act, the Middle East would war with itself. Forever. Imagine Saddam Hussein and his sons in power, or the Assads, and there is no force for good to overthrow them. Moreover what if a dictator appears and unifies the warring factions, as has happened so many times before? Israel, the only democracy, would be threatened and would possibly be backed into a corner and have no choice but to use its nuclear weapons.

Those who beat their swords into plowshares will plow for those who keep theirs.

Aula

April 11, 2019 at 10:21 am

It looks like this article concludes the topics for 1992 that you listed at https://www.filfre.net/2018/06/ebooks-and-future-plans/ (which incidentally puts you ahead of both The Adventure Gamer and The CRPG Addict). What plans do you have for 1993?

Jimmy Maher

April 11, 2019 at 10:42 am

Yes, will have another state-of-the-blog address soon to announce the 1992 ebook and move us into 1993. It’s a big one — Myst and Doom, CD-ROM going mainstream, SVGA graphics arriving, etc. One might even call it the linchpin year of computer-gaming history. Look at almost any game and, while you might not be able to guess its exact year of release, you can feel pretty sure whether it was released pre- or post-1993.

Liz Danforth

April 11, 2019 at 11:04 pm

Thanks for a blast from the past, and the kind words about the heart and the work that went into the game (from nearly everyone who touched the games’ creation, development, and delivery).

I remember how much Mike Stackpole and I were aghast by what Paramount refused to let us do from the first outlined ideas. We really wanted it to be the “missing year” of the five year mission, and pick up so many dangling loose ends from the series itself. (As just one example, What *was* the deal with the green Orion slave girl in the end credits? That seemed like an obvious tale to tell. We wanted to explore and explain, but Paramount said no.)

I also remember hearing how much DeForest Kelley HATED the dialog he had to deliver in Judgment Rites. In our own defense, we weren’t screenwriters but wordsmiths who expected our words to be read, not read aloud. We had a lot to learn, for all that, but I’ve always cringed since Kelley was my favorite among the three.

Thanks again!

Ross

April 12, 2019 at 8:50 pm

Hm. I don’t really recall the combat being nearly so awful as everyone else remembers, except if you failed the copy protection and were punished with a nigh-unwinnable battle. I do recall there being a missable thing you could do in one mission that would increase the power of your torpedoes, though I never really quantified how much.

Would love to see televised star trek give a little nod to the possibilty of turning the brightness all the way up to locate cloaked ships though.

Brian Bagnall

April 27, 2019 at 10:13 pm

Interplay made another Trek game after Judgement Rites called Star Trek: Starfleet Academy in 1997. I’ve never played it but Wikipedia says the sales were decent.

On another topic regarding layout, typically the photo/image comes after the text references the topic in the image.

Jimmy M: “Please don’t tell me how to do layout. It sickens me.”

Jimmy Maher

April 29, 2019 at 9:29 am

You took the words right out of my mouth. ;) But seriously, it’s a judgment call. Text is a linear medium, and sometimes I want the reader to have *seen* what I’m talking about before I talk about it. And sometimes it feels better to introduce the subject and then show the illustration.

Brian Bagnall

April 30, 2019 at 3:11 pm

Great article by the way! I loved the first Star Trek adventure by Interplay but am not too sure if I graduated to the sequel. In light of your explanation of the increasing difficulty of space battles, I’m not even sure I finished the first one. That would have been pretty demoralizing not to be able to finish off a great game and might have precluded me from moving on to the sequel (and judging from the lower sales, that might have impacted others). It just doesn’t feel right to move onto part two if part one is still lingering unfinished.

I can see your point about the location of images and there are probably instances where it makes more sense to show it prior to discussion. I’ve been using the McGraw-Hill style manual for a while and have grown accustomed to it. From purely a reader’s experience, when a new image appears without context, the reader can feel confused because it doesn’t seem to have anything to do with the article, and may even wonder if it was put there in error. Typically they skip the photo and keep reading and usually don’t go back to it. Whereas when the photo comes after some discussion in the text, the ideas have been planted in the reader’s mind and they’ll pore over it longer and with greater interest.

Beau

May 5, 2019 at 1:30 pm

Agree on the stilted dialogue, but I love Majel Barret’s voice so much that I have played these games and consulted the computer for hours just to hear her talk.

Scott Everts

June 2, 2019 at 11:57 pm

Very interesting article on these games. I started work at Interplay in 1991 and was a QA guy on the 25th Anniversary game. I moved to a designer on the CD-ROM edition which included an expanded version of the last mission. After that was an Associate Producer on Judgment Rites mostly focusing on the management of the background paintings.

It’s great to see so much research on these titles. Don’t think many people remember them.

The early version of Starfleet Academy was based on original series design and we made a intro movie for it. I had a copy of the original Paramount contract in my file cabinet and discovered that we also had rights to make games based on the movie era content too. So that’s why Starfleet Academy switched to the movie era look. As development continued on SA, I moved out of Trek based games and worked on Stonekeep and eventually joined Black Isle after working on Fallout.

Thanks again for doing these articles, I try to visit this site every few months. I’m now at Obsidian Entertainment which has several old Interplay guys still there. :)

Wolfeye M.

October 26, 2019 at 7:35 am

I never played 25th Anniversary or Judgement Rites. I’m hesitant to check them out because of the adventure game elements.

But, I did play a lot of Interplay’s later Star Trek games. Starfleet Academy was amazing, even if it did make the ships feel like X-wings zipping around and not stately and majestic ladies like the Enterprise.

But, my favorite by far was Starfleet Command. You play as a new starship captain, go on missions, work your way up through the ranks, hopefully not getting blown to bits in the process. I still say it had some of the best starship combat ever, every other Star Trek game not in that series doesn’t quite measure up.

Oh, and by the way, I prefer TNG to TOS. Part of it may have to do with me being born around the time the show was on the air, I never saw anything but reruns. But, I’ve also watched TOS. I call Kirk the Jerk, because that’s how he acts, and I always keep wanting him to die so they’d make Spock Captain. So many missed opportunities when he inevitably gets them in trouble and some poor redshirts killed. Picard’s command style is better, he listens to his crew, instead of walking all over them. Makes the show more enjoyable for me. But, to each his or her own, I guess.

Derek

January 13, 2020 at 4:28 am

Despite having grown up with TNG, I have to admit that it has a rather sterile feel to it, which only its best episodes rise above. Opinions will differ about whether that sterility is more or less tolerable than the original series’ 1960s hokiness. Deep Space Nine, on the other hand, is largely a different animal from the other Star Trek series, and more dynamic and more vivid than any of them.

Sam Robbins

December 11, 2019 at 9:57 am

“Indeed, no Star Trek game since the two Interplay titles discussed in this article has revisited the original show.”

Actually Star Trek Online released their Agents of Yesterday expansion back in 2016 that has you start back in the TOS era, complete with visuals to match and many callbacks to original episodes. It’s pretty fantastic if you’re a TOS fan actually, not to mention a pretty good (and free to play) game in it’s own right.

Jimmy Maher

December 13, 2019 at 3:30 pm

Thanks! Added the qualifier “standalone.”

Marco

June 12, 2020 at 3:43 pm

I haven’t yet played 25th Anniversary but I have played Judgement Rites. It’s a bit strange in places, but so was the original series. The game’s biggest win is that it captures all the main tropes of the series without slavishly repeating storylines. So while you normally expect an adventure game to have a consistent tone, here you alternate between action-filled, Escape from Colditz style sections, and sections that are quiet meditations on morality and the nature of free will. I agree that the ending of the No Man’s Land episode is emotionally powerful, and is carefully not spoiled until it comes.

The Starfleet scoring of each mission is clever in theory but a bit frustrating in implementation. To get a perfect score, which the player is incentivised to do, you often need to have scanned something that there was no particular reason to scan or made a non-intituitive choice, thereby pushing you to consult a walkthrough each time. There is also one bit of space combat that you are actually meant to lose, but of course you assume that will ruin your perfect score and so spend ages trying to achieve the almost-impossible.

Josh Martin

July 28, 2021 at 6:00 pm

Amidst it all, the team making Star Trek: 25th Anniversary kept plugging away — but, inevitably, the game fell behind schedule. September of 1991 arrived, bringing with it the big television special and the Nintendo Entertainment System game, but Interplay’s own tie-in product remained far from complete.

An interesting side note here is that, although Konami held the license to make Trek games for the NES and Game Boy, they subcontracted the actual development to other companies, with the NES version being handled by… Interplay! The resulting game shares the PC version’s combination of graphic adventure and space combat gameplay, and while drastically simplified by comparison it’s still a damn sight better than Konami’s dire NES port of King’s Quest V. (The Game Boy version was an unrelated game by another developer, and must not have been a big priority for Paramount given that it flagrantly violates their prohibition on “plot elements derived from episodes which were already part of the Star Trek legend”—the central objective is to stop the “Doomsday Machine” as seen in the eponymous second-season episode, though other than this the story is completely different.)

Tim Kaiser

October 2, 2021 at 4:28 am

I agree that the mediocre voice acting from the main cast, but especially William Shatner, was very disappointing. The voice actors of the random NPCs all do a decent job though. If you watch the old Animated Series from the 70s, the voice acting there from the main cast is pretty bad too. With the PC games, all them were in the twilight of their careers so it is understandable that they might phone in the performance for an easy pay check. However, with the Animated Series, it’s a bit more of a head scratcher since they were all working actors and Star Trek was a cult phenomenon at that point but the movies and blockbuster status of the franchise was still years away. I guess they’re just bad at doing voice acting.

Mike

June 23, 2024 at 8:00 pm

It’s very interesting! I even haven’t heard about those adventure games.

I think that it would be interesting if you will take a look at two “pure” Star Trek themed space combat simulators made by Interplay: Starfleet Academy (1997) and Klingon Academy (2000), the latter remains as I can gather, a cult classic among Star Trek fans: also Klingon Academy (at least judging from the tutorial) is closer to how you describe combat in Star Trek than in Star Wars.

Steve Pitts

September 14, 2024 at 4:56 pm

“my bachelor degree in literature”

Now this might be an English vs. American thing, but I would expect that to read ‘bachelor’s degree’

Cheers, Steve

Jimmy Maher

September 17, 2024 at 2:43 pm

Thanks!

Andy

January 2, 2026 at 10:03 pm

I just want you to know that kiddie me, who owned 25th Anniversary, found the adventure game segments baffling but spaceship combat a thrill. I spent 90% of my time with that game intentionally warping wrong so I could have space fights. So we DID exist.

Ben

January 22, 2026 at 5:45 pm

red shirt -> redshirt

a la -> à la

costumes). -> costumes.)

disapointing -> disappointing

Jimmy Maher

January 23, 2026 at 10:55 am

Thanks!