Steve Barcia started thinking about his second grand-strategy game well before he had finished creating his first one. While he was waiting for his latest iteration of Master of Orion to compile each day in the cramped Austin, Texas, offices of his company SimTex, he sketched in the mental details of a follow-up that would take place in a fantasy rather than science-fictional milieu. As soon as the one game was finished, he wrote up a design document for the next one and shared it with the rest of the SimTex staff. Within two weeks, they were charging full-speed ahead on Master of Magic. It would ship under the MicroProse imprint in time for the Christmas of 1994, only a year after its predecessor, despite being one of the most complex strategy games yet made for a computer. If there’s no rest for the wicked, it would seem that Barcia and company had been very bad indeed.

Given the new game’s title and its short development cycle, one might suspect it to be little more than a reskinned Master of Orion. In reality, though, such could hardly be further from the truth. Master of Magic is a wildly different experience from Master of Orion, enough so that one would scarcely guess it to have come from the same designer. Where Master of Orion is polished to perfection, its every element carefully considered and tested, Master of Magic is a far more ramshackle affair, a pile of diverse ideas thrown together — some more fully realized than others, some literally not working at all if we want to get pedantic about it. Nevertheless, it all comes out okay in the end; the game’s variety, generosity, and sheer chutzpah win through. Master of Magic is simply fun — every bit as much fun as Master of Orion. Just don’t try this at home, budding designers.

Master of Orion was frequently billed as “Civilization in Space” by a slightly lazy press. It’s therefore ironic to note that it’s actually Master of Magic which betrays a major influence from Sid Meier’s 1991 magnum opus. Barcia began laying down the basics of his first game in the late 1980s, and thus its mechanics and interface are most indebted to the conquer-the-galaxy board and computer games which appeared before that point. By the time he started on Master of Magic, however, Barcia had had plenty of time to play and admire Civilization and to clone some of its approaches. It’s thus at least a bit more defensible to call Master of Magic “Fantasy Civilization,” as was and is done from time to time, even if doing so still falls well short of a complete description. Certainly the magazine Computer Gaming World made no bones about it in its review of the game:

The city display will be familiar to players of Sid Meier’s Civilization. In fact, we wouldn’t want to suggest that the same code was used, but it sure looks like it could have been. From the graphic representation of the buildings themselves to the rows of farming, working, and rebelling citizens, the city display is a near-verbatim copy of the earlier design.

The city-management screen in Master of Magic, which is almost a carbon copy of the one in Civilization. Many of the systems behind it work exactly the same as well.

This, then, is one important aspect of Master of Magic. You start with a single village which you must grow and develop. Meanwhile you send out settlers to found other cities, or armies to conquer ones that already exist. You improve your cities by ordering their populations to build structures that increase their production or otherwise cause them to function more efficiently. All of this will be very familiar indeed to any Civilization veteran. That said, the city-building side of Master of Magic is generally simplified in comparison to Civilization. There is, for example, no tech tree to research in order to unlock new types of buildings. Instead buildings themselves unlock other buildings, as shown by a handy chart included in the manual: constructing a builder’s hall unlocks the granary, shrine, library, miner’s guild, and city walls; constructing a granary unlocks the farmer’s market; etc., etc. Steve Barcia, who was eager for understandable reasons to ensure that the similarities to Civilization weren’t overstated, explained the simplifications by noting that the two games had fundamentally different design goals: “Civilization focuses on internal problems. In Master of Magic, it’s the external; it’s conquest.”

The main Master of Magic screen, where you examine the map and move your units around. While it departs a bit more from the layout of Civilization than does the city-management screen, the inspiration remains obvious, right down to the shortcut keys.

So, although you move your units around the map exactly as you do in Civilization — to be fair, that game in turn borrows the approach from the much older Empire — things go in a dramatically different direction once combat begins: Master of Magic places much more emphasis on combat than does Civilization. In the latter game, each unit moves independently over the map; in Master of Magic, you form larger armies by “stacking” up to nine units together. When two units bump into each other on the world map in Civilization, one loses and is completely destroyed and the other wins and survives completely intact, all depending on a single roll of the virtual dice which is compared against their respective attack and defense ratings. In Master of Magic, by contrast, combat takes place on a separate screen, with plenty of room for your tactical genius to make its presence felt. Units here can be “wounded” by having only some of their number killed, needing time to heal and replenish themselves.

Fighting a tactical battle. Given that I have only one group of halberdiers against seven groups of zombies and one of skeletons, my best option here is to flee — assuming I don’t have a Turn Undead spell at my disposal, that is.

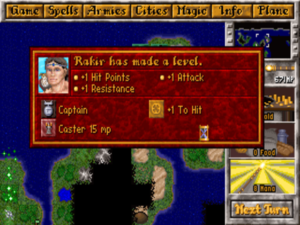

But the most important addition of all to the combat model, the game’s first real stroke of genius, is that of experience points: as units fight and survive battles, they become better, tougher and stronger, able eventually to punch well above their rookie weight. Granted, Civilization too has the barest inkling of this; a unit which wins a battle there has a chance of becoming a “veteran,” with a bonus to its attack and defense. Master of Magic, however, takes the concept to another level entirely. And then it adds a second stroke of genius: heroes, individual captains who can be recruited to join your cause and lead your armies into battle. They too earn experience and improve their skills; you can even find or make magical weapons and armor for them.

In the context of its own day, Master of Magic thus joined Julian Gollop’s X-COM, which was released about six months before it, as one of the foremost exemplars of a new trend in strategy games, that of using CRPG elements to forge a more personal, even emotional bond between the player and the figures she commands. It works brilliantly here, just as it does in X-COM. You come to identify deeply with your units and especially your heroes as you nurture their development, and come to mourn the loss of one of them almost like that of a real friend.

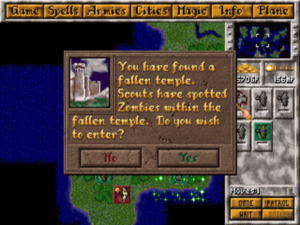

The debt which Master of Magic owes to the CRPG genre extends to other areas as well. Its randomly generated maps are seeded not just with neutral and enemy towns but with “fallen temples,” “abandoned keeps,” and “mysterious caves.” You can send your units and heroes to confront what is found within, if you dare; your reward for doing so is booty and the experience they earn, assuming they survive. Just exploring the world, revealing and clearing out more and more of the map, is thoroughly enjoyable even before you meet any of the computer players who are doing the same thing.

But it’s the game’s third and final layer rather than the city building or unit management that is its most defining attribute, not to mention the source of its name. The fact is that you really do play a master of magic, a wizard competing to conquer the world against up to four other wizards under the control of the computer. As such, you have spells at your disposal… boy, do you have spells. The magic system draws heavily from Magic: The Gathering, the collectible card game of fantasy combat that took the culture of tabletop gaming by storm in the early 1990s. Magic here is divided into five “books”: Life, Nature, Sorcery, Chaos, and Death. When you begin a new game, you choose your wizard from a list of fourteen possibilities, each of which specializes in one or two books of magic and has some other individual advantage to boot. Or, if you’re playing at one of the higher difficulty levels, you can also build your own wizard from scratch.

Most hardcore players wouldn’t think of playing with anything other than a customized wizard; you see one of them being made here. Not being much of a power gamer, I’m generally happy taking one of the fourteen pre-made wizards, which offer plenty of variety in themselves.

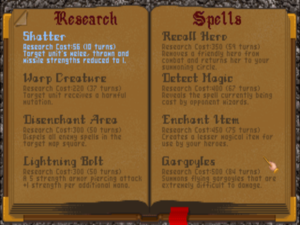

Either way, you enter the game with just a few low-level spells in your particular book or books. In place of the technological research trees of Civilization and Master of Orion, here you research new spells. Their number and variety are positively mind-boggling: there are 40 spells associated with each book, plus 16 that everyone can learn regardless of specialty, for a total of no less than 216 in the game as a whole. But Master of Magic borrows a trick from Master of Orion to great effect: not all of the potential spells in your books are available for research on any given playthrough, meaning that the sort of rote strategies that are possible in climbing Civilization‘s static research tree cannot be relied upon here. Because you get a different set of possible spells even if you play the very same wizard twice in a row, you constantly have to think on your feet. Needless to say, your overall strategy must be dictated to a large extent by the spells that show up in your research list. If you gain early access to Floating Island, for example, you have a handy means of crossing oceans before your opponents may be able to; if not, you might need to build expensive shipyards early on in at least some of your coastal cities.

Your source of spell-research points is mana, which you harvest from the land’s so-called “places of power.” It’s the most essential resource in the game, and thus the source of some agonizing decisions. For mana, you see, is not only important for research. You must balance the amount of it which you devote to research against that which goes to casting spells in the field and that which goes to improving upon your innate spell-casting capabilities; this last category of mana, in other words, serves as your wizard’s equivalent to experience points.

You change the ratio of mana you devote to various purposes by manipulating the three staffs to the left.

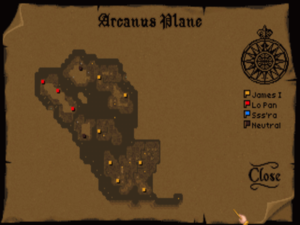

The thoroughgoing watchword of Master of Magic is variety, applying not only to the list of spells but to every aspect of the game. The sheer amount of stuff here would be impressive in a modern game, and was well-nigh unprecedented at the time of this one’s release. In addition to choosing one of fourteen starting wizards, you choose a starting race for her to command from another fourteen possibilities; each of these races comes with its own unique set of units to be unlocked and raised, as well as a unique mix of buildings that it can erect in its towns. You can choose a world with small, medium, or large land masses, with weak, normal or powerful magic. All these possible starting parameters alone ensure that the game will take a long time indeed to get old. Then, once you actually begin to play, you find an absurdly wide array of monsters to contend with, heroes to recruit, and magical arms and armor to dredge up. And then there are all those spells: spells to buff your units and heroes and to nerf your enemies’, to summon fantastical creatures to join your ranks, to disrupt your foes’ own magic. Eventually your powers become downright Biblical, as you control the winds and blight your enemies’ fields and forests — but be aware that they can potentially do the same things to you. By way of a final touch, you have not one but two complete worlds to explore and conquer; there are two separate dimensions in the game, the relatively mundane Arcanus and the magic-rich realm of Myrror. You can move between them by means of special portals on the landscape which you must discover and secure — or, inevitably, via yet another spell you can research. It will take you a long, long time to see everything that Master of Magic has to offer.

Master of Magic‘s huge diversity of content does as much as its theme and its core mechanics to give it a very different personality from that of its predecessor Master of Orion. I love both games just about equally, but most others I’ve talked to tend to express a marked preference for one or the other. Board-game aficionados often speak of two schools of design, named after their typical continents of origin: the Eurogame, where a fairly small number of moving parts is carefully tuned for a perfectly coherent, perfectly balanced, Neoclassical experience; and the “Ameritrash” game, which is distinguished by its Romantic exuberance in throwing everything but the kitchen sink into the mix, just to see what will happen. It’s hopefully clear by now that Master of Magic is very much the latter sort of game. While there are whole worlds of emergent strategy to be found in all of its variety, there are also moments of friction when things don’t quite gel.

The most disappointingly half-baked aspect of Master of Magic is, perhaps not coincidentally, its one feature that actually was lifted wholesale from Master of Orion: its diplomatic model. You communicate with the other wizards here just as you do with the leaders of the other alien races in the older game, but it’s harder to divine why you should do so. In some circumstances, it’s possible to win a game of Master of Orion without ever firing a shot in anger, by persuading your counterparts to vote you into supremacy via clever diplomacy. Master of Magic, however, lacks any equivalent victory condition; the only way to win here is to wipe out your foes. This fact turns your negotiations over treaties and favors into an even more cynical exercise than it is in Master of Orion; it’s a foregone conclusion that absolutely everyone is only playing for time before unsheathing their trusty daggers for the backstab. Further, there’s little ultimate point to all of your diplomatic contortions. Any opposing wizard who agrees to a peace treaty is probably weak enough that you can defeat her in war, or is just trying to milk a little bit more tribute out of you before she declares war on you three turns later. There’s very little reason to ever even initiate diplomatic relations, other than perhaps to trade for a spell you have an urgent need for. I know that I tend to ignore diplomacy entirely, and have never felt overly disadvantaged by it — a statement one could never make about Master of Orion. When playing Master of Magic, I do sometimes find myself missing the intricate dance of negotiation in Master of Orion, which can be as exciting as any space battle — but then, Master of Magic is, as I’ve already noted, a very different game.

Those who’ve played Master of Orion will find this menu very familiar. Alas, it’s used to far less compelling effect here.

One consequence of your inability to schmooze your way to victory is a drawn-out endgame, a problem all too typical of these types of grand-strategy games which Master of Orion manages to deftly avoid thanks to its Galactic Council. There comes a point in every game of Master of Magic when you know you’re going to win — or the opposite. Assuming it’s to be the former, everything becomes a bit rote from that point on, even as conquering those last pesky cities of your enemies can be quite time-consuming. Although you can win by advancing all the way up the spell-research tree and casting the “Spell of Mastery” instead of wiping out all of your opponents militarily — this is the game’s equivalent of blasting off for Alpha Centauri in Civilization — that process is even more time-consuming. And because all of the enemy wizards rush to attack you with everything they have as soon as you start to research the Spell of Mastery, your game is still guaranteed to end in genocidal total war.

Master of Magic also runs afoul of another typical problem of its genre which its predecessor mostly manages to sidestep: the micromanagement bugbear. Most players develop a consistent pattern for building up their cities early on, one which they vary only under special circumstances. While the game does offer a “vizier” who can manage your cities for you, his choices tend to be hopelessly nonsensical. A way of setting up building queues in advance for each city, coupled ideally with a default queue you could define for yourself, would have been a wonderful addition. As it is, you’re in for an awful lot of busywork in the later stages of building your fantasy empire.

One final area of the game that’s frequently singled out for criticism is the artificial intelligence of your opponents, which leaves a lot to be desired. In the grand tradition of Civilization and Master of Orion, cranking up the difficulty level doesn’t make the other wizards smarter; as far as I can determine, it doesn’t actually change their set behaviors at all. What it does do is cheat on their behalf ever more egregiously, by giving them bigger and bigger production bonuses. Many understandably find this solution to the problem of making the game challenging for the veteran player to be less than ideal.

Still, a recent development in the small but surprisingly active world of ongoing Master of Magic fandom provides an object lesson in being careful what you wish for. Just this year, a group of fans, working in association with the current owners of the game’s intellectual property, released Caster of Magic, a comprehensive patch/expansion that, among many other things, dramatically upgrades the artificial intelligence. Personally, I find it no fun whatsoever, and I’ve heard many others say the same thing. Playing against its smart, ruthless, ultra-agressive enemy wizards only served to clarify for me what I really enjoy about Master of Magic: exploring the worlds, building up my units and heroes, researching and trying out new spells. For me, it’s as much experiential CRPG as zero-sum strategy game. If I could add something to the game, it would be more diverse encounter areas, possibly with elements of story to them, to further emphasize these qualities. This is not to say that you’re wrong to play in a different way, wrong to enjoy the game for other reasons; certainly there are many who love what Caster of Magic does to the game. It does, however, serve to illustrate that the field of ludic artificial intelligence, which is so often characterized as simply the struggle to make the computer play just like a human, becomes more complicated than that formulation just as soon as it collides with real-world game design.

Caster of Magic is in fact merely the latest example of a long tradition of patching Master of Magic, stemming from the fact that the game as originally released desperately needed all the patching it could get. Both before and after their acquisition by Spectrum Holobyte in 1993, MicroProse was among the publishers most prone to ship games before their time in response to external financial pressures. As one of the company’s big titles for the Christmas of 1994, Master of Magic fell victim to this unfortunate tendency. In yet another marked contrast to Master of Orion, Steve Barcia’s second grand-strategy game shipped so riddled with bugs that it was essentially unplayable; the game crashed more often than not during battles. (“Save every turn, save before every battle, save every time you can,” became the player’s rule of thumb as summarized by Computer Gaming World.) A series of patches gradually solved the worst of the issues, but there remain to this day spells in the game that don’t quite work correctly. Master of Magic could have used its own incarnations of Alan Emrich and Tom Hughes, the two outsiders who took an early interest in Master of Orion during its development and offered so much feedback and practical advice over the months that followed that co-designer credits wouldn’t have been out of order. Failing that, just a few more months in the oven and a round or two of proper testing could have done much for it.

Although its overall reception was gravely impacted by its unconscionable state at the time of its release, a small group of players fell in love with the game for its crazy multitudinousness and kept its memory alive for years, then decades. They did so not least because Master of Magic became the opposite of Master of Orion in one final, supremely ironic way: whereas Master of Orion spawned about a thousand 4X rule-the-galaxy copycats of varying degrees of quality, nobody else has ever done a game quite like Master of Magic. The year after it appeared, New World Computing released Heroes of Might and Magic, a superficially similar blending of strategy and CRPG elements, but one that was dramatically different in the details: it was a more tightly focused effort, with pre-crafted maps in place of randomly generated worlds, a modest but carefully tuned suite of spells and creatures in place of a decadent cornucopia of same, and a multi-mission story-oriented campaign in place of a wide-open sandbox to play in. When Heroes of Might and Magic — admittedly, a superb game in its own right — became the hit that Master of Magic had not, it became the model for fantasy strategy games going forward.

So, Master of Magic remains a unique experience to this day. While it’s definitely no paragon of balanced game design, its rambunctious riot of possibility ensures that it stays interesting over the long term; this is one quality that it certainly does share with Master of Orion. In fact, I like to play Master of Magic just like I play that game: I throw the dice to set up the parameters of my world, my wizard, and my minions, and then have at it, assured that, whatever awaits me, it will be completely different from the last time I played. That’s the kind of variety that can keep you playing a game forever.

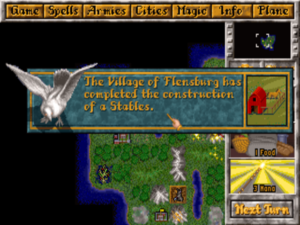

Each race has its own set of city names. Those of the barbarians are real-world German cities — including Flensburg, where my wife grew up. What’s up with that?

(Sources: Computer Gaming World of September 1994, December 1994, January 1995, May 1995, and October 1995; PC Gamer of January 1995; Electronic Entertainment of January 1995; Computer Player of February 1995; Next Generation of January 1995; InfoWorld of December 1994; Interactive Entertainment CD-ROM of October 1994 and November 1994; Hyper of June 1995.

Master of Magic is available for digital purchase at GOG.com.)