What is it that we love about Sherlock Holmes?

We love the times in which he lived, of course, the half-remembered, half-forgotten times of snug Victorian illusion, of gas-lit comfort and contentment, of perfect dignity and grace. The world was poised precariously in balance, and rude disturbances were coming with the years, but those who moved upon the scene were very sure that all was well — that nothing ever would be any worse nor ever could be any better…

— Edgar W. Smith

The Lost Files of Sherlock Holmes: Case of the Serrated Scalpel was an unusually quiet sort of computer game. It was quiet when you played it, being a game that rewarded contemplation as much as action, and one that placed as much emphasis on its text as its audiovisuals. It was quietly released in 1992 by Electronic Arts, a publisher well along by that point in their transition from being a collective of uncompromising “software artists” to becoming the slick, bottom-lined-focused populist juggernaut we know and don’t always love today. And yet, despite being so out of keeping with EA’s evolving direction, Serrated Scalpel quietly sold a surprising number of units over a span of several years.

That unexpected success had consequences. First it led EA to fund a 1994 re-imagining of the game for the 3DO living-room console, featuring video clips of live actors voicing dialog that had previously appeared only as text on the screen. And then, with the MS-DOS original still selling at a steady clip — in fact, rounding by now the magical 100,000-unit milestone — it led to a somewhat belated full-fledged sequel, which was released in mid-1996.

The Lost Files of Sherlock Holmes: Case of the Rose Tattoo was largely the work of the same crew that had made its predecessor, notwithstanding the gap between the two projects. Once again, R.J. Berg, a former EA manual writer and perpetual Sherlock Holmes fan to the Nth power, wrote the script and generally masterminded the endeavor. And once again a small outfit called Mythos Software, based in Tempe, Arizona, handled all of the practicalities of the script’s transformation into a game, from the art to the programming.

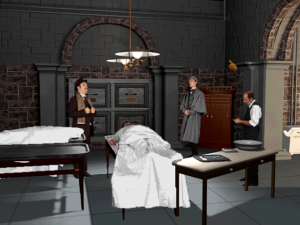

Indeed, Rose Tattoo as a whole is very much a case of not fixing what wasn’t broken in one of my favorite adventure games of the 1990s, so much so that I almost fear that this review will come across as superfluous to those who have already read my homage to the original. The one really obvious difference is a reflection of the four years separating the two games’ release dates, over the course of which the technology of the typical home computer advanced considerably. So, Rose Tattoo is able to present its version of Victorian London with a more vivid clarity, thanks to a screen resolution of 640 X 480 rather than 320 X 200. More ingeniously, Mythos has found a middle ground between the pure pixel graphics of the original game and the awkwardly spliced video clips of the 3DO remake. “Sprites” made from real actors are shrunk down and inserted directly into pre-rendered 3D scenery, making an almost seamless fit.

Otherwise, though, Rose Tattoo is the purest form of sequel, striving not just to duplicate but to positively double down on everything its precursor did. In some contexts, that might be read as a condemnation. But not in this one: Serrated Scalpel was such a breath of fresh air that more of the same can only be welcome.

Once again, then, we have here a plot that is ironically more believable than the majority of Arthur Conan Doyle’s own Sherlock Holmes tales. Like Broken Sword, another standout adventure from the standout adventure-gaming year of 1996, Rose Tattoo kicks its proceedings off with a literal bang: it opens with Sherlock’s portly brother Mycroft Holmes getting seriously injured by an explosion at his Diogenes Club that everyone is all too eager to blame on a gas leak — “the price of progress,” as they all like to say. Even Sherlock initially refuses to believe otherwise; deeply distraught over his brother’s condition, he retreats into his bedroom to take refuge in his various chemical addictions. Thus you actually begin the game as John Watson, trying to dig up enough clues to shake Sherlock out of his funk and get him working on the case.

Once that has been accomplished, the game is truly afoot. Rather than a random gas explosion, the “accident” at the Diogenes Club turns out to be a deliberate murder plot that is connected to the theft of vital secrets from the British War Office. Your need to avenge Mycroft’s suffering will plunge you into the geopolitics of the late nineteenth century; you’ll even meet face to face with the young Kaiser Wilhelm II of the newly minted nation of Germany, who is depicted here as an intelligent, cultured, and to some extent even open-minded leader, one whose political philosophy has not yet hardened into the reactionary conservatism of his First World War persona. The game captures in their nascent form the political changes and even the evolution of the weaponry of war that would lead to the horrific conflicts of the first half of the twentieth century.

But that is only a small piece of the history which Rose Tattoo allows us to witness up close and personal. The usual videogame’s view of history encompasses war and politics and little else. Rose Tattoo, on the other hand, fastidiously recreates a fascinating time and place in social history, when the world that we know today was in many ways in the process of being invented. Your investigation takes you across the width and breadth of Victorian London and to all of its diverse social strata, from fussy lords and ladies who seem to be perpetually singing “Rule, Britannia!” under their breath to underground radicals who surface just long enough to preach their revolutionary philosophy of Marxism at Speaker’s Corner every Sunday. You visit clubs, hospitals, police departments, morgues, flats, townhouses, lofts, squats, mansions, palaces, monuments, tailors, bathhouses, billiard rooms, photography studios, animal emporiums, parks, gardens, aerodromes, laboratories, greengrocers, phrenologist’s offices, minister’s offices, barrister’s offices, warehouses, and opium dens, all of them presented in rich, historically accurate detail. “When a man is tired of London, he is tired of life,” said Samuel Johnson. Indeed.

As in the first game, Sherlock Holmes’s iconic flat at 221B Baker Street serves as the starting point of your investigations and the home base to which you continually return. In addition to being a tribute to Sherlock’s wide-ranging curiosity, it’s a vastly more effective virtual museum of Victoriana than the real one that stands at that London address today. Spend some time here just rummaging about, and maybe follow some of its leads with some independent research of your own, and you’ll begin to feel the frisson of life in this amazing city, the melting pot of the Western world circa 1890. A small sample of the exhibits on hand:

- A portrait of the now largely forgotten abolitionist hero Henry Ward Beecher, who was arguably the most famous American in the world for a decade or two.

- A portrait of General Charles George “Chinese” Gordon, “the brave if not brilliant commander” who earned his nickname helping to put down the Taiping Rebellion and later “died defending Khartoum in ’85.”

- Some of London’s many newspapers, which, “though ephemeral, are among the wonders of the age,” being the first near-instantaneous form of mass media, the finger on the pulse of the world’s greatest metropolis, humming with all of its news, gossip, and scandal.

- Music by such less remembered composers as Pablo de Sarasate, César Franck, and Jacques Offenbach, placed here to serve as a reminder that the Romantic music scene of the late nineteenth century included more names than Brahms, Tchaikovsky, and Wagner.

- A book by French criminologist Alphonse Bertillon, the inventor of the mug shot as a tool for law enforcement.

- More books, including “Mommsen’s masterful history of Rome,” “C.F. McGlashan’s grisly account of the Donner party,” and “a particularly inept translation of The Brothers Karamazov.”

- Pictures of the convicted and executed murderers Thomas Griffiths Wainewright, William Palmer, and Louis Lingg (the last of whom may very well have been innocent), assembled as part of the dogged but consistently fruitless Victorian effort to scientifically discern character through facial features.

- An early wax-cylinder phonograph, marking Sherlock as his era’s version of those early adopters who in 1996 were playing this game on the latest personal computers.

But lest all of this start to sound like a tedious exercise in “edutainment,” know that the whole experience is enlivened enormously by R.J. Berg’s writing, which is even more finely honed here than it was in the first game, managing to be both of the time it depicts and an ongoing delight to read in 1996, 2022, or any other year. He takes a special delight in lacerating with delicate savagery the city’s many stuffed shirts, useless layabouts, and pretentious fools. (Perhaps we can learn something about character from appearance after all, at least in the world of this game…)

- Chinless and tending to fat, this young man sits like a beluga whale in a steam cabinet. His hooded eyes are partially closed and rivulets of sweat pour down his face. It is not possible to say whether he is enjoying himself.

- The lady masquerades as a debutante. Dressed in a hideous crepe gown, she has the carriage of a Palladium chorus girl. Possessed only of pretensions, she displays none of the high style to which she aspires.

- The corpulent, self-important clerk is fussily dressed. If he runs true to form, he spends his leisure time and money indulging passions for art books and Belgian chocolates.

- The man could pass as a mortician or a bank manager. Below his high domed forehead, his pale, pitted face wears a preternaturally neutral expression. The slow reptilian oscillation of his head is disconcerting.

Then there’s my absolute favorite turn of phrase: “Bledsoe awaits with the equanimity of a ring-tailed lemur in a room full of rocking chairs.“

And yet Berg seldom punches down, and is by no means without compassion for the ones who were not born with silver spoons stuck firmly up their derrières: “Like thousands of indigent girls, she was sucked to the city at fourteen by the promise of twelve pounds per annum and a bed in the attic. After 40 years in service, enduring drudgery, discomfort, insult, and every sort of meanness, she has risen to become Assistant Housekeeper at the Cavendish Hotel.”

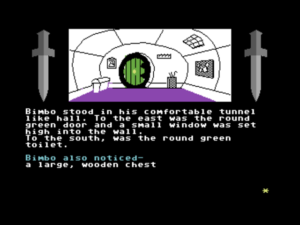

Sherlock, Watson, and the indomitable Wiggins, head of the Baker Street Irregulars, outside 221B Baker Street. While the game’s graphics aren’t breathtaking, they are, like everything else about it, quietly apropos.

Investigating a suspicious death in the morgue. There will be more than one such corpse to examine before all is said and done.

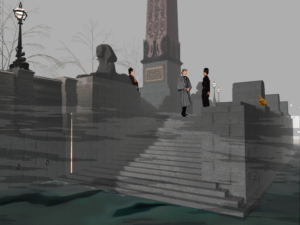

On one of the newly constructed Thames Embankments, next to Cleopatra’s Needle, recently looted by the British Empire from Alexandria.

The bucolic environs of St James’s Park. We have need of that boy’s new pet dog, which happens to be the best tracker in all of London. Hmm… what could we offer the boy for it?

In addition to gobs of historical verisimilitude and some of the best writing to appear in a game since the heyday of Infocom, Rose Tattoo shares with its predecessor a gratifyingly grounded approach to puzzles. There are problems to solve here, many of which veteran adventure gamers will find very familiar in the abstract, such as the inordinate quantity of human gatekeepers who must be circumvented in one way or another in order to gain access to the spaces they guard. But, instead of employing ludicrously convoluted solutions that could only appear in an adventure game, solving these “puzzles” mostly entails doing what a reasonable person would under similar circumstances. A surprising number of the gatekeepers can be bypassed, for instance, simply by acquiring an official letter from Scotland Yard authorizing you to investigate the case, then showing it to the obstacle in question. Rose Tattoo resists the adventure genre’s centrifugal drift toward slapstick comedy as well any game ever made; Sherlock never gets up to anything really ridiculous, never surrenders his dignity as the world’s most famous detective. He does nothing in this game that one couldn’t imagine him doing in one of Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories.

As must be abundantly clear by now, I love this game dearly; it joins Serrated Scalpel on the short list of my favorite point-and-click graphic adventures of all time. It must also be acknowledged, however, that it aligns crazily well with my own background and interests. I spent my years in and around university immersed in this setting, reading tens of thousands of pages of Dickens, Eliot, and Trollope (the last being my favorite; as Prime Minister Harold Macmillan once said, “there’s nothing better than going to bed early with a Trollope”). And yes, I read my share of Arthur Conan Doyle as well. Playing Rose Tattoo is like coming home for me.

But, to state the obvious, I am me and you are you, and your experience of Rose Tattoo may very well be different. I can all too easily imagine another person finding this game more exhausting than fascinating. It’s out of step with the fashion even of 1996, never mind today, in that it expects you to read all of its long descriptions; only the diegetic words — i.e., those actually spoken by the characters in the game — are voiced. And you can’t just ignore all of the Victorian bric-à-brac that litter its many scenes because there is in fact a smattering of vital clues and objects to be found amongst the clutter. Further, there’s little here to satisfy hardcore puzzle fiends; that ancient adventure-game saw of the newspaper shoved under the door to retrieve the key pushed out of the lock with the pin is about as elaborate as things ever get from that perspective. Solving the mystery rather hinges on collecting physical evidence, interviewing witnesses, and deducing on a broader canvas than that of the individual puzzle.

Of course, a point-and-click adventure game is a discrete possibility space, which means that you could solve the mystery by brute force — by going around and around and around the map of London, talking to everyone and picking up whatever isn’t nailed down and showing it to everyone. But to do so would be to miss the point entirely, in addition to subjecting yourself to mind-numbing tedium. I would rather encourage you to make full use of the in-game journal, in which the tireless Watson records every word of every conversation Sherlock has, and which can even be saved as a text file for perusal outside of the game. (Incidentally: all of the text, in the journal and elsewhere, uses British spellings, despite this being an American game — another nice touch.) I would encourage you, that is to say, to enter into the spirit of the thing and really try to solve the mystery yourself, as a real detective might. I can promise you that it does hang together, and that the game will reward you for doing so in a way that very few other alleged interactive mysteries — excepting its precursor, naturally — can match. If all of those words in the journal and locations on the map start to feel overwhelming, don’t worry about it: just take a break. The mystery will still be waiting for you when you come back. The Victorian Age was a foreign country; they did things more slowly there.

But if all of that is still a bit too tall of an order in this hurly-burly modern world of ours, that’s okay too. No game is for everyone, and this one perhaps less so than many. Certainly it was an anomaly at the time of its release, being about as out of step with an increasingly go-go, bang-bang gaming market as anything could be. Doubtless for that reason, EA released it with almost no fanfare, just as they had its predecessor. Alas, this time it didn’t defy its low expectations once it reached store shelves: it didn’t become a sleeper success like Case of the Serrated Scalpel. The magazines seemed to pick up on the disinterest of the game’s own publisher. Computer Gaming World, the closest thing the United States had to a gaming journal of record, never even gave it a full review, contenting themselves with a two-paragraph capsule summary whose writer betrayed little sign of ever having played it, who made the inexplicable claim that it “tried too hard to be an interactive movie”; in reality, no 1996 graphic adventure was less movie-like.

So, that was that for the Lost Files of Sherlock Holmes series. R.J. Berg continued working for EA as a producer, designer, and writer for years, but on less unique fare that gave him less opportunity to deploy his deliciously arch writerly voice. Mythos Software survived until about 2003 as a developer of multimedia educational products — they were behind the popular BodyWorks series of anatomical explorations — but never made another straight-up game.

Still, to complain that we didn’t get more of these games seems churlish. Better to be thankful that the stars aligned in such a way as to give us the two that we do have. Check them out sometime, when you’re in the mood for something a bit more on the quiet and thoughtful side. Maybe, just maybe, you’ll come to feel the same way about them that I do.

(Sources: Electronic Games of February 1993, Computer Gaming World of January 1997. Also Mythos Software’s now-defunct home page.

Like its predecessor, The Lost Files of Sherlock Holmes: Case of the Rose Tattoo has never received a digital re-release. It is, however, supported by the ScummVM interpreter, so getting it running isn’t too much of a challenge on Windows, MacOS, or Linux once you acquire the original CD or an image of same. As of this writing, you can find several of the latter on archive.org, including one version that is already packaged up and ready to go with ScummVM. Just search for “sherlock rose tattoo”; I prefer not to link directly to avoid bringing unwanted attention to their existence from our friends in the legal trade.

And if you enjoy this type of contemplative sleuthing, you might also be interested in the Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective board games, which play like analog versions of this game — perfect for a lazy late-summer afternoon on the terrace with a tall glass of something cold and the company of a good friend or two.)