Games are not made in a vacuum.

This truth ought to be self-evident, but it’s often lost in histories of gaming. People like me tend to rely, perhaps a bit too much, on what I sometimes call the cataloging approach to gaming history. You all know the recipe for such articles: start with a discrete classic (or occasionally infamous) game, add a narrative of who made it and how they did so, pour in an evaluation of its merits and demerits, and season the final concoction with a description of its place in the evolution of gaming in general. I’ve written plenty of such articles in the past, and will doubtless write plenty more of them in the future.

What such articles sometimes lose sight of, however, is a broader cultural context that’s to be found beyond the permeable borders of the gaming ghetto. The ideas and influences that are turned into games come from all over the place, being reflections of the societies that surround them and the interests of the people who make them. (For much of gaming history, these people have been mostly young white and Asian men from fairly privileged socioeconomic circumstances, which, needless to say, has had its own impact on the types of games that exist and the subjects they tackle.) Sometimes the pop culture that influences games is so blindingly obvious that we almost can become blind to it: what would digital games be today if Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson had never invented the tabletop game of Dungeons & Dragons, or if J.R.R. Tolkien had never written The Lord of the Rings, or if George Lucas had never made Star Wars? But it’s the subtler influences that I find most interesting to ferret out — like, for instance, the way that techno-thriller author Tom Clancy’s brand of American military triumphalism fed into the combat simulations made by companies like Microprose, which at times commanded a quarter or more of the overall computer-gaming market during the 1980s and 1990s.

When I realized a decade or so ago that I had somehow stumbled into writing a broad, encompassing history of computer gaming, I promised myself that I would try to bring out connections like these whenever possible. I’m not sure that I’ve always kept that promise on an article-by-article basis, but I have always tried to keep one eye at least on the bigger picture, to give this site some credibility as a broad cultural history rather than just a catalog of neat games that appeared down through time — not that it hasn’t also been the latter, of course. In short, I’ve always wanted to understand how outside culture bleeds into the seemingly insular world of gaming, and how gaming has left its mark on the world outside its boundaries. (This last has barely begun to happen at the point in history we’ve reached now, more than ten years into this project, but rest assured that the “gamification” of everyday life is not that far away.) There are many reasons to play old games, the most popular ones being simply because they’re fun on their own merits and because of the warm and fuzzy feelings of nostalgia they invoke in us folks of a certain age. But another reason, which is no less defensible, is that they give us a chance to become time travelers in a more impersonal sense, by giving us a direct pipeline to a receding past.

So, please indulge me now in a case study about how changing fashions in the way we view one of the most enduring mytho-historical tropes of modern culture impacted games. The sinking of the brand-new, “unsinkable” luxury liner the Titanic following a collision with a North Atlantic iceberg on the night of April 14, 1912, is the delicious tragedy that we just can’t seem to let go of, an irresistible mixture of symbolism, theme, romance, pathos, mystery, and heroism to which we keep returning over and over. Just as many historical novels have more to tell us about the times in which they were written than the times they allegedly chronicle, the lens through which we view the Titanic has been as much a mirror we hold up to our contemporary selves as a window into the past. For example, during the unsentimental, materialist 1980s, the last full decade before our virtual online existences started to compete with our flesh-and-blood reality, the Titanic was discussed primarily as a thing, to be found, probed, and perhaps even raised above the waves once again. But then, in 1997 — an altogether dreamier, more fanciful time to be alive — a hit film reminded us why we had all fallen in love with the Titanic to begin with: because it’s such a great story, or rather collection of them, a beautiful canvas for our imaginations. My next three articles will examine these competing visions of the Titanic, and the games that were made in response to them — no fewer than ten games in all, plus one intriguing idea for a game that was never made.

The first person to propose finding and raising the Titanic from its watery grave did so barely a year after the ship had sunk. Charles Smith was a Colorado mining engineer who knew nothing about ships or the sea, but was convinced that his own area of expertise was as applicable to the problem of a seaborne salvage operation as it was to that of cracking open an elusive new seam of gold. It seems that when one goes through life with a miner’s hammer in one hand, everything looks like a suitable nail. “My object is to deliver the Titanic to its owners without further injury so that the great vessel may be rebuilt,” Smith declared. “Much of the cargo, or all of it, would be recovered. All the bodies which sank with the doomed ship have long since been embalmed by the action of the seawater, and when they are at last brought back to the surface they will be easily identifiable and prepared for reverential burial.”

Smith’s plan hinged on electromagnets, one of the trendy technological wonders of his age. He would build a massive one — possibly the most massive one ever built — sail or drag it out to the Titanic‘s last known location, turn it on, and let the sunken ship’s steel hull pull it to its bosom. With the wreck thus pinpointed on the ocean floor, he would descend in a custom-made submarine to attach hundreds more magnets to the hull, each with a rope leading back to a steam-powered winch aboard one of a dozen or so boats on the surface. When all was ready, the winches would all be activated in unison, and the 46,000-ton vessel would be slowly lifted back to the surface, then towed to a dry dock, repaired, and placed back into service. Smith estimated that the whole operation would require just $1.5 million and 162 men, and would take about three months: one month to find the wreck, one month to prepare it, and one month to raise it and tow it to safety. “It is merely a matter of magnets,” he insisted.

The plan left something to be desired in terms of basic physics, not to mention in its understanding of basic human psychology; how many passengers would really want to sail on a ship on which more than 1500 people had died in horrific circumstances? Yet it was taken bizarrely seriously in the popular press, which churned out excited headlines like “Can the Lost Titanic Be Raised?” Alas, potential investors proved less credulous: Smith managed to raise just $10,000 of the $1.5 million he said he needed. After the onset of the First World War, a more diffuse tragedy than the sinking of the Titanic but one that was many orders of magnitude more immense, he and his scheme faded back into obscurity, just another of the frivolous pipe dreams of a more innocent era.

More than half a century later, in the late 1960s, a British odd-jobber and Titanic obsessive named Doug Woolley captured headlines with a scheme that was almost as outlandish as that of Charles Smith. He would attach 200 deflated pontoons all around the Titanic‘s hull. Then they would be filled with hydrogen which would be extracted from the surrounding seawater via electrolysis, and the ship would rise majestically to the surface like the mother of all hot-air balloons. He said the whole operation would cost about £4.8 million and could be accomplished within one year.

To say that Woolley lacked qualifications in deep-sea salvage hardly begins to state the case. He was working in a pantyhose factory at the same time that he was holding press conferences about raising the Titanic. He had never personally sailed farther than the width of the English Channel, and was conducting what he insisted were groundbreaking experiments in electrolysis in his dingy flat’s bathtub. And he was rather putting the cart before the horse anyway, given that no one knew precisely where the Titanic lay; whereas Charles Smith had at least made some attempt to address that part of the problem, Woolley just took it on faith that it would turn up when he started to look around for it.

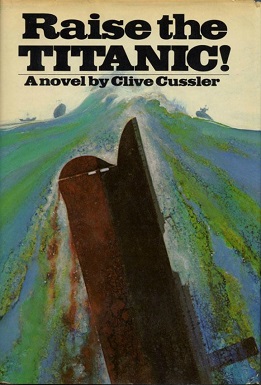

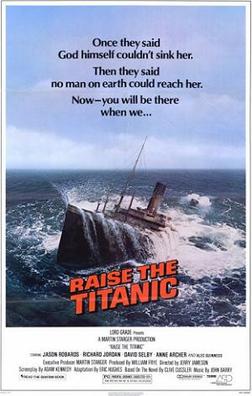

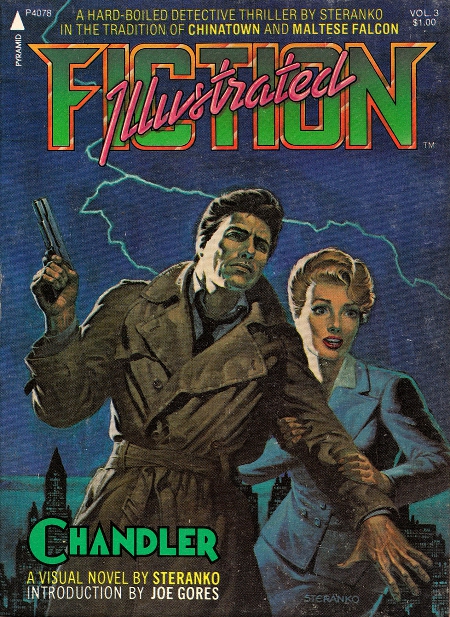

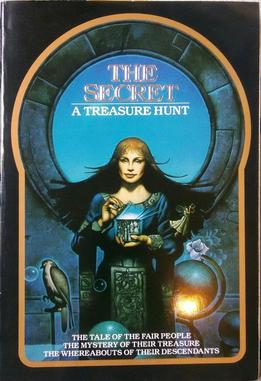

Wooley’s dream never had a chance in the real world, but the world of fiction was another matter. In 1976, the American author Clive Cussler published the third of what would become many pulpy adventure novels featuring his hero Dirk Pitt, a sort of Tom Swift for grown-ups. The novel was called Raise the Titanic!, and had a plot involving byzanium, a precious (and fictional) mineral, a radioactive power source whose potential dwarfs that of uranium or plutonium, whose only known reserves happened to be aboard the Titanic on that fateful night. Pitt and his friends concoct a plan for raising the ship — why they don’t just try to raise the byzanium in its hold is never adequately explained — that bears distinct similarities to Doug Woolley’s scheme: they will seal off the interior of the ship and pump it full of compressed air to cause it to float to the surface. This they succeed in doing, fighting off Soviet saboteurs all the while.

The novel became a bestseller, whereupon Hollywood made it into a big-budget summer movie in 1980. The scale model of the Titanic that was constructed for the film’s climactic scene of the ship breaking the ocean’s surface cost $7 million, as much as the original vessel when not adjusting for inflation. But surprisingly, even the Titanic name and a titanic budget worthy of the ship couldn’t save the film; it was savaged by critics, and turned into a box-office bomb. “It would have been cheaper to lower the Atlantic,” quipped its producer Lew Grade later.

Although the method employed by Dirk Pitt and his friends for raising the Titanic was hopeless for a vessel of this size at this depth, it was adapted from real-world techniques already in use for raising ships that had sunk in shallower waters. For a cottage industry of shipwreck recovery had arisen after World War II. With an estimated quarter of a million or more ships having sunk since humanity first began to ply the world’s waterways, the pickings in the most popular sea lanes were rich. People made fortunes by poring over old nautical records, searching doggedly where the ships they found in them were believed to have sunk, and retrieving the gold, silver, and other valuable in their holds. The Caribbean, which had once positively teemed with Spain’s treasure-laden galleons sailing from the New World back to the Old, was particularly fertile ground.

Meanwhile others had invented the new field of maritime archaeology, with the purpose of studying and preserving the wrecks they found instead of looting them for profit. Soon every other issue of National Geographic seemed to contain some new undersea discovery, illustrated in full-color Kodachrome. For example, the Titanic‘s sister ship the Britannic, which had struck a German mine and sunk off the coast of Greece in 1916 while serving as a hospital ship, was found by the famous French undersea explorer Jacques Cousteau in 1975.

Admittedly, the boundaries between the treasure hunter and the maritime archaeologist weren’t always clear. Many of the adventurous folks who got into this racket had a little bit of both in them, along with a hefty hankering for the notoriety that would come their way if they became, say, the first person to send back pictures of the most famous of all sunken ships in the world.

The problem with the Titanic, the thing which made it so much harder to find than the likes of the Britannic, was that it had sunk in the deep water of the open ocean rather than the coastal water of the Mediterranean. The deep ocean floor is the most inaccessible geography on our planet; even today, marine scientists like to say that we know more about the surface of Mars than we do about the landscapes under our own planet’s oceans. That said, people did come up with various ideas for locating the Titanic from the ocean’s surface that were more or less feasible. For example, Commander John Grattan, the Royal Navy’s anointed expert in diving and submersibles, proposed scouring the ocean floor with a huge active sonar array towed behind a trawler. But such plans would be dauntingly expensive to implement. And, even if the Titanic was found from the surface, what next? Only a few submersibles in the world were capable of diving to the wreck’s depth of two and a half miles below the ocean’s surface, and they were all in the hands of the United States Navy, which wasn’t in the habit of renting them out to private treasure hunters to use for snapping pictures and collecting souvenirs.

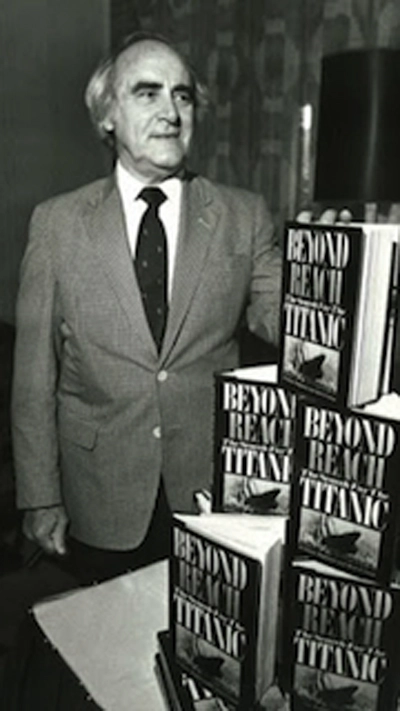

One man, however, judged that the fame and money that would follow a credible claim of just having found the Titanic — never mind the photographs, much less any salvage operations — would be enough to make the task eminently worth taking on. “Cadillac” Jack Grimm was a flamboyant Texas oilman with a taste for exotic adventure and pseudoscience, who had already mounted expeditions in search of Bigfoot, the Abominable Snowman, and the Loch Ness Monster, who had once traveled to the North Pole in the hope of proving that the Earth was hollow. His greatest achievement to date in this mold, at least if you asked him, was the recovery of a piece of Noah’s Ark from the side of Mount Ararat in Turkey — never mind that the scientific community universally scoffed at his alleged find.

In the summer of 1980, while Raise the Titanic was bombing in box offices, Grimm funded a search for the real ship that was broadly similar to the approach suggested by John Grattan: a trawler dragged behind it a sonar array which hovered a few hundred feet above the ocean floor. Over a period of more than a week, the boat methodically covered an area of about ten square miles that was judged the most likely to contain the wreck. It returned to port without a smoking gun, but its crew did create a list of fourteen sites within the search area that had sent back suspiciously regular sonar echoes, any of which could be indicative of a large human-made object like the Titanic. “I think we got that heifer corralled in a box canyon,” Grimm told the press in his usual colorful diction.

Indeed, Grimm knew how to work the press like the master of ceremonies at a rodeo, and he poured on the juice now. He announced that he would mount a second expedition the following summer to exhaustively search each of the fourteen sites with a more sensitive sonar array, an iron-detecting magnetometer, and a camera capable of sending back grainy photographs. He arranged this time to borrow from the Coast Guard the Gyre, a cutting-edge oceanographic research vessel, and funded a documentary film that was to be hosted by Orson Welles; the film crew would sail with the second expedition in order to capture the instant of discovery. He was, he told the assembled journalists on the day he himself sailed with the Gyre, absolutely convinced that he would be known to the world as the man who had found the Titanic by the time his feet next touched dry land.

Looking for an expert to support, debunk, or qualify his showy optimism, some journalists turned to one Robert Ballard, an oceanographer and diver with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute who was arguably the world’s foremost expert on deep-ocean exploration of a more scientific bent, whose greatest achievement to date had been his discovery of underwater hydrothermal vents and the unique forms of animal life that clustered around these precious oases of warmth on the bitter-cold ocean floor. The polar opposite of Grimm in temperament, the cautious Ballard said that, while Grimm’s overall approach was viable if conducted carefully and thoroughly, it would nevertheless be difficult to convince the public that he truly had found the Titanic absent high-quality, closeup photographs of the wreck. He was diplomatic enough not to add that Grimm’s earlier trafficking in mythical monsters and Biblical literalism would cause any claim he made to seem that much more dubious without overwhelming proof.

Meanwhile Grimm’s expedition set to work, contending with unstable weather that kept the Gyre‘s captain on a constant knife-edge. One by one, the crew eliminated the promising locations that had been identified the previous year. As the number of remaining possibilities dwindled, the mood onboard grew dimmer and dimmer. At last, the fourteenth and final site was crossed off the list. They had come up dry.

Or had they? On the way home, flipping in desultory fashion through the photographs that been returned to the surface, Grimm stumbled upon an image that gave him goosebumps: something that looked for all the world like a large human-made object, smoothly tapered like the wings of an airplane, rising out of the mud of the ocean floor. He was sure it must be a blade from one of the Titanic‘s 26-ton propellers.

Grimm immediately radioed the Coast Guard and asked to hang onto the Gyre for another week. But the Coast Guard refused, even when he name-dropped President Ronald Reagan, whom he claimed was a close personal friend. There was nothing for it but to continue the journey home. He was certain he had found the Titanic, but even his own team of experts, never mind outsiders, were unconvinced. They said that the blurry photograph was more likely than not just another rocky outcropping. An extraordinary claim required extraordinary proof, and this one picture was not it. Which didn’t stop Grimm’s documentary, once it was finished, from claiming it to be all but conclusive proof.

Grimm did try one more time to seal the deal. In the summer of 1983, he set off again aboard a research vessel, borrowed this time from Columbia University. But this trip was plagued by even worse weather than the last one. After several days of frantic searching for a propeller which seemed to have disappeared back into the ocean floor whence it had sprouted, 40-knot winds forced him to cut the expedition short. Grimm, who was prone to seasickness and had a deadly fear of water, decided enough was enough after this latest miserable experience. He never mounted a fourth expedition.

But the Titanic wasn’t to remain hidden much longer. For even as Jack Grimm was capturing headlines with his expeditions, Robert Ballard and his colleagues at Woods Hole were quietly developing an uncrewed deep-water sled equipped with an array of powerful searchlights and high-resolution still and video cameras, all operable by remote control from the surface. He called it the Argo, after the ship which the mythical Greek hero Jason had sailed into the unknown sea that lay beyond the Hellespont. Being not without a streak of public-relations savvy of his own, Ballard thought it would be quite a coup to use his expensive new toy to find and send back images of the Titanic, an achievement for which Grimm had obligingly primed the press’s pump.

That, at any rate, was how the story was reported in the 1980s. A more complicated and truthful version emerged years later. It seems that the United States Navy had funded much of the Argo‘s development and construction, with the understanding that it would be able to use it and its creator from time to time for its own purposes. (Ballard had longstanding relationships in the Navy, having served from 1967 to 1970 as an active-duty officer and being still a reservist.) The first favor was called in almost as soon as the Argo was ready for action. The Navy brass were very concerned about two nuclear attack submarines which had been lost in the 1960s in the North Atlantic, not far from where the Titanic had gone down. They were eager to ensure that the subs’ reactor cores had not ruptured and, just as importantly, that the Soviets hadn’t found the vessels and looted them for secrets. A search for the Titanic would make the perfect cover story for Ballard’s activities in this otherwise deserted stretch of open ocean. The Navy gave him two months to play with; if he completed his classified investigations more quickly than that, he could use the rest of his time to really search for the Titanic. As it happened, it took him slightly over a month and a half to find the two submarines and put the Navy’s mind at ease that neither was leaking radioactivity and neither had been plundered. He was left with twelve days in which to find the Titanic.

Ballard and his Argo were sailing aboard the research vessel Knorr, the workhorse of Woods Hole. That same summer, a French team under an oceanographer named Jean-Louis Michel had tried to find the Titanic using sonar, but had come up empty. This failure, combined with the failures of Jack Grimm’s expeditions, convinced Ballard that he shouldn’t be looking for a reasonably intact ship on the ocean floor; the area had been scoured so thoroughly with sonar by now that such an object would surely have been found if it existed. He believed that the ship must be far more badly damaged than had been previously assumed — in fact, that it had possibly broken into many pieces during its long plunge to the bottom. Instead of looking for a whole ship, he would look for the debris left by a sinking ship. Since sonar had no way of distinguishing small bits of human-made rubble from the natural detritus of the ocean floor, the only way to conduct such a search was visually, using the Argo‘s camera feeds. Time was short, the area to be searched was large, and this was an exhaustingly tedious way to go about it, but he would do what he could before he had to head home.

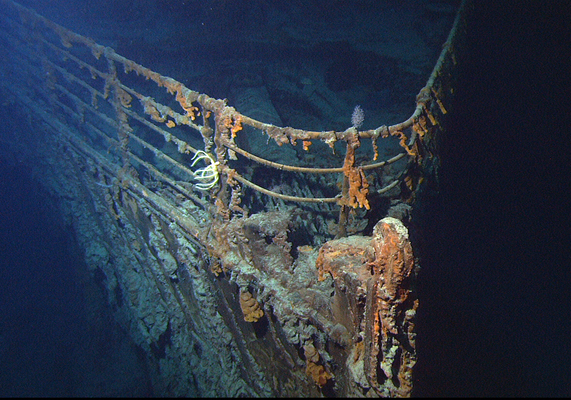

The twelve days were half up on the early morning of September 1, 1985, when, with Ballard fast asleep in his cabin, a shout went up from the Argo control room: “Wreckage!” By the time Ballard had burst into the room, the crew had zeroed in on a clearly manufactured metal object that they were certain was a boiler for the great ship’s engines. Everyone in the cramped little room burst into spontaneous cheers. But then, just as quickly, the mood turned sober. “We realized we were dancing on someone’s grave, and we were embarrassed,” remembered Ballard later. He suggested that they all observe a moment of silence. This they did, and then they got back to work.

Ballard and company carefully traced the “debris field” they had found back to each of its termini. At one end lay the front half of the ship, intact enough to still be readily recognizable for what it was; at the other end lay the rear half, so badly mangled that it looked like little more than a colossal pile of rusted metal and other junk. It was obvious what had happened: the ship’s back had broken as it plunged beneath the waves, and the two halves had separated completely from one another and finished the long fall separately, raining boilers, supports, furniture, bric-à-brac, and doubtless plenty of now-vanished human corpses from their open ends down onto the ocean floor between the two, like a gigantic busted piñata.

Needless to say, this discovery caused all but the most committed of dreamers to give up on any hopes of raising the ship. Grimm’s “propeller” lay well away from the real wreck site, proving to be nothing more than the unusual rock formation so many scientists had suspected it to be. On the other hand, it would later emerge that Grimm had towed his sonar array within 500 feet of the real ship’s bow back in 1981. Robert Ballard had been both very good and very, very lucky — a potent combination in any endeavor.

The September 3, 1985, edition of The New York Times included a small article printed near the bottom of the front page: “Wreckage of Titanic Reported Discovered 12,000 Feet Down.” It was the first trickle in what would become a torrent of media coverage. Soon the first photographs began making their way back from the North Atlantic — haunting images of a propeller (the real one this time), of a cabin porthole, of crockery and pots and a stoking port for the boilers. The killer shot captured much of the ship’s bow, its shape unmistakable to even the rankest layperson.

At this point, the story becomes for better or for worse as much a tale of mass media as exploration and discovery. Robert Ballard became more than just a run-of-the-mill celebrity; “folk hero” is a better description of his status. He returned to the wreck in the summer of 1986 with a crewed submersible called the Alvin, one of those aforementioned few vehicles in the world capable of withstanding the almost inconceivable cold and pressure that exist two and a half miles below the ocean’s surface; Ballard’s enviable connections had allowed him to borrow this unique vessel from the Navy. The photographs he came up with this time were stunning, allegories of splendid desolation fit to be framed and hung in a Romantic poet’s library. The press and the public they served couldn’t get enough. They experienced vicariously the same emotions Ballard had felt as he gazed out the window of the Alvin: “As I peered entranced through my viewport, I could easily imagine people walking down the promenade, looking out of the windows I was now looking into. Here I was on the bottom of the ocean gazing at recognizable, man-made artifacts. I was looking [at] decks along which [people] had walked, rooms in which they had slept, joked, made love.”

The wreck of the Titanic was simply inescapable for the next few years in the United States, Britain, and much of the rest of the world, the subject of newspaper and magazine articles, books, documentary films, museum exhibits, and even tourism; charter companies sold expensive junkets out to the spot in the ocean directly above the wreck. And, as with any media sensation worth its salt, there were also controversies. Jack Grimm resurfaced with a spurious legal claim, quickly dismissed by the courts, that he rather than Robert Ballard was the rightful discoverer of the wreck by virtue of having passed so close to it with his sonar array. And already in 1987 a dodgy outfit managed to mount an underwater expedition of its own to the site, damaging the wreck in the process of grabbing a handful of objects that were later unveiled in a tacky syndicated-television special. Host Telly Savalas and his panel of “experts” pawing through these precious artifacts was the twentieth-century equivalent of the amateur archaeologists of the nineteenth century blasting away at the interior of the Pyramid of Khufu with gunpowder.

The Titanic wreck site has continued to attract both earnest maritime archaeologists and shameless profiteers ever since, along with every gradient in between the two. But our interest today is in the early years of the Titanic mania spawned by the initial search for and discovery of the wreck. It’s time for us to turn in that context to computer games, a very young form of media at the time Jack Grimm and Robert Ballard were making headlines, but one that was already responding to and reflecting the broader landscape of old media around it. In the case of the Titanic mania, this led to an entire sub-genre of games about the discovery of, exploration of, and in some cases the raising of the famous luxury liner. I’ll reveal upfront that none of these games is a deathless classic. Yet each is an instant of cultural history, suspended in the digital ether like the Titanic in its underwater grave.

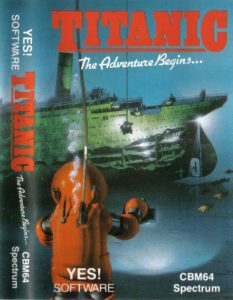

The earliest game I know of which tackles the subject of the discovery and salvage of the Titanic predates Robert Ballard’s finding of the wreck by well over a year. Released in early 1984 in Britain only for the Sinclair Spectrum, the oddly titled Titanic: The Adventure Begins… is rather a reflection of the hype which surrounded Jack Grimm’s three expeditions. It was re-released two years later in not only the original Spectrum but a Commodore 64 version, doubtless in response to the news of Ballard’s discovery. It’s very much a product of the collective sugar rush that was the early British games industry, when just about any enterprising bedroom coder could slap a game together, pay a duplication house for a run of cassettes containing it, pay a print shop for a simple insert for the case, and sell the end result for a few quid in corner software shops all over the country.

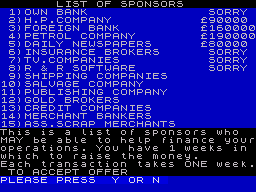

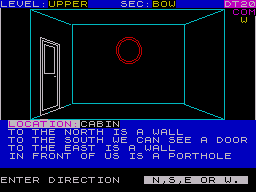

Programmer Paul Hill, who called himself R&R Software, was clever enough to recognize that at least a third of the battle of finding the Titanic was funding the expedition. Accordingly, the first of the three radically different stages of his game involves finding a sponsor and outfitting your boat and crew, whilst keeping enough cash in reserve to pay your running costs once you head to sea. Stage two is the search for the wreck, which you conduct by sending diving teams down to promising locations identified on the NASA satellite photo you hopefully purchased during the previous stage; matters are complicated here by the icebergs that dot the ocean’s surface. Finally, stage three lets you actually explore the wreck, which in this alternate reality sits on the ocean floor conveniently intact. This stage, the most elaborate by far, is an exercise in mapping a three-level maze of almost 500 locations, looking for the game’s MacGuffin, a fortune in gold that supposedly went down with the ship.

Paul Hill’s knowledge of the realities of deep-water exploration is clearly nonexistent; the scuba divers he imagines frolicking through the wreck would have been crushed like bugs before they made it halfway down to 12,500 feet. Nor is his game any paragon of thoughtful design; much of your success or lack thereof depends on blind luck. Nevertheless, there’s a certain gonzo charm to the thing, a product of a time well before gameplay genres calcified into a set of straitjacketed expectations, when a game could do and be almost anything its programmer could dream up and dare to implement with the primitive tools at his disposal. In this sense, it’s a time capsule par excellence. I only wish I could hear the song which Paul Hill put on the tape’s flip side, an “epic rock track” by a bunch of his mates who called themselves Rare Breed. Sadly, this exposure did not lead to a record deal…

(You can download the original Spectrum version of Titanic: The Adventure Begins… from this site. Note that you’ll need a Spectrum emulator such as Fuse to run it.)

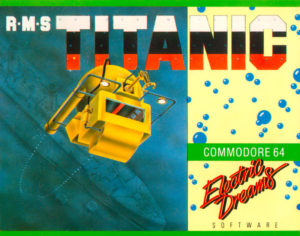

In Sinkable, his recent book-length meditation on the wreck of the Titanic and the hold it continues to exert on our imaginations, Daniel Stone writes that “the complexity of salvage can make it painfully boring. Like building an amusement park or passing a law, the process is far less interesting than the finished product. The film Raise the Titanic was a commercial flop because the title was the most breathtaking part.” Much the same might be said about many of the games featured here; an archaeological expedition to the Titanic is one of a surprisingly large number of possible game subjects which sound exciting in the abstract, but which are damnably difficult to turn into a satisfying gameplay loop once you drill down to the details. Unsurprisingly, then, those designers who came closest to making a compelling go of it were the ones who were willing to season their simulations with a degree of whimsy. The British game R.M.S. Titanic, which was also released in the United States as a budget title under the name of Titanic: The Recovery Mission, is a case in point.

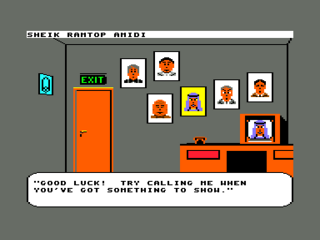

Appearing in Britain in early 1986, R.M.S. Titanic technically postdates Robert Ballard’s discovery of the real ship, but was probably already in development before that point. It’s the product of a small studio who called themselves Oxford Digital Enterprises, whose one previous game was thoroughly in keeping with the highbrow expectations engendered by that name, being a four-stage journey through William Shakespeare’s Macbeth that was published at the height of the bookware boom. R.M.S. Titanic, which was released for the Commodore 64 only, is by contrast all of a piece. Although you have to manage your finances and logistics much like in The Adventure Begins, you do so side-by-side with your exploration of the wreck.

All of the facets of this game are much more involved. You have half a dozen fickle backers whom you must keep mollified in order to keep the funding coming in; this you do by recovering alluring artifacts from the wreck and generating favorable press coverage. Indeed, working the press is another important part of the game. You field questions from reporters in press conferences, trying to tailor your responses to the organs they write for; the Titanic Historical Society has different priorities than Pravda.

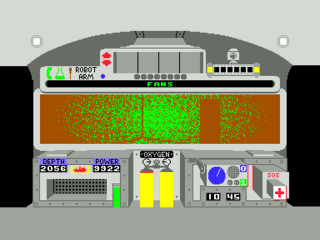

But the heart of the game still takes place underwater, as it should. The game presumes that you have already located the wreck, and thus focuses only on your exploration of same with an uncrewed, remote-controlled submersible, which is simulated in some detail. You control its movements, set the intensity of its light, and can pick up and manipulate objects using its mechanical arm, keeping one eye always on its battery level; running out of juice under the ocean is disastrously expensive. As in The Adventure Begins, the ship here is conveniently intact, a maze of decks and rooms to be explored. Here, however, your way is blocked by lots and lots of locked doors. The game’s fanciful side comes to the fore via your method of opening them: each door is a little object-combination puzzle. For example, you might need to combine a cherry with a sundae in order to open the door that leads into an ice-cream parlor.

The game’s fiction, such as it is, has it that a previous expedition has already placed eight deflated balloons in the ship, then somehow lost track of where they are (and apparently locked all of the doors behind themselves). Your ultimate goal is to reach all of the balloons and inflate them, in order to raise the ship to the surface. As must be abundantly clear by now, there is much about this game that makes no sense whatsoever. If you’re wondering how a sundae and a cherry have survived for more than 70 years on the ocean floor, I’m afraid I don’t have an answer for you.

Still, much the same sense of giddy possibility clings to R.M.S. Titanic as to The Adventure Begins, combined with more sophisticated programming. The underwater scenes are almost unnervingly atmospheric despite — or because of? — the low resolution of the graphics, all flickering light peering into the eerie gloom. I remember being quite captivated by this game for several weeks as a young teenager, even though I never got very far in it.

For its difficulty is its real Achilles heel. As you move deeper and deeper into the ship, the object combinations you must divine grow more and more esoteric and the sheer quantity of objects and geography to reckon with grows more and more daunting. The first documented instance of anyone solving this game dates from after the millennium, when a patient German named Stefan Schönfelder finally accomplished the feat by making extensive use of emulator save states. The ending sequence proved predictably underwhelming; in this era of gaming, the journey had to be its own reward.

(You can download R.M.S. Titanic from this site. Note that you’ll need a Commodore 64 emulator such as VICE to run it.)

By the late 1980s, the shift to more powerful computers made a credible full-on simulation of marine archaeology seem like an increasingly realizable possibility. This would prove a mixed blessing, for all of the reasons listed by Daniel Stone above.

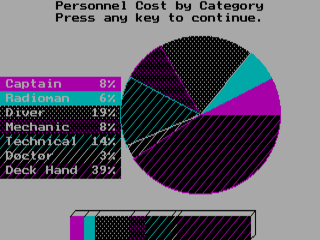

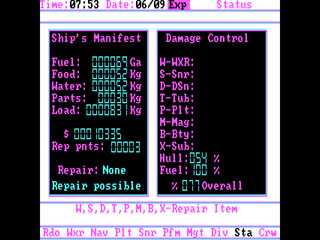

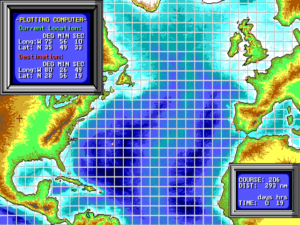

Search for the Titanic was released in 1989 by the American budget software house Capstone, who were best known for casino simulations. There were a flagship version for MS-DOS and a heavily redacted one for the trusty old Commodore 64. Despite or because of having been “reviewed for authenticity by the staff of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute,” it’s one of the most brutally boring computer games ever made. The broad strokes are familiar: you have to deal with the business aspects of an expedition to the Titanic alongside the seaborne bits. This time out, however, you have to build up your reputation and financing by exploring a dozen or so less famous wrecks before you get a crack at the Titanic.

The actual dives are almost totally beyond your control; the game is primarily a simulation of finding the location of the wrecks from the surface. In this and much else, the designers’ guiding principal seems to have been, “Implement all the boring stuff, but be sure to leave out all the fun stuff.” If this is what you get when you do the research and take marine archaeology seriously, give me scuba divers swimming around at 12,500 feet and doors with ham-sandwich-activated locks any day.

There are two things that I find hilarious about this game. The first is that your reward for slogging through this simulation that has less pizazz than your average Excel spreadsheet is a set of digitized photographs of the wreck; it reminds me of those awful games of computerized strip poker I used to play as a sexually frustrated teenager, giving a whole new dimension to the neologism “disaster porn.” The other is that someone recently saw fit to dredge this stinker of a game up off the bottom and put it up for sale on a digital storefront for a fiver. To call that an audacious move is the understatement of the year. For, as Trent Nickson wrote in his 2005 review of Search for the Titanic for the Lemon 64 website, “I don’t really know how you could tart this game up to make it fun.” Suffice to say that the designers never even tried.

(The truly dedicated gaming historians among you can buy this game from GOG.com.)

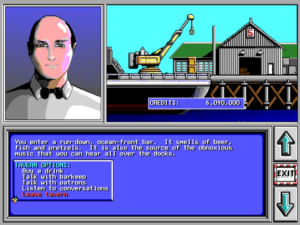

Thankfully, someone else did try very hard to make marine archaeology fun. Sea Rogue was the first game by a small San Diego studio called Software Sorcery, and was published by Microprose for MS-DOS on their Microplay budget label in 1992. It was created with the assistance of a retired Navy captain whose expertise was underwater salvage, and was billed as a simulation. None of this sounds overly promising in light of the previous game in this survey.

But when you start to play the thing, it quickly becomes clear that Software Sorcery has made an aesthetic rather than a literal simulation — a game which endeavors to give you a taste of its real-world subject matter, but which never overwhelms you with boring detail, which understands that games need to be fun first and foremost. The Titanic is pushed somewhat into the background here; it’s just one of about 150 different wrecks you can find and explore, from the Spanish treasure galleons that litter the floor of the Caribbean to such other legendary modern wrecks as the World War II German battleship Bismarck. Sea Rogue is by far the most ambitious game on this list; there are a lot of moving parts here. I want to say that it’s the best game here as well.

The older game which Sea Rogue immediately brings to mind, even before any of the ones above, is the Sid Meier classic Pirates!. You start out in Norfolk with an old trawler, eager to make your fortune as a wreck hunter. So, you sail up and down the east coast of the United States and into the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, seeking clues to wreck sites at each port of call. As you find and dive the wrecks and sell off the loot you acquire thereby back on land, you gradually improve your boat and your equipment. Eventually, you’ll have enough dosh to replace your rusty old tub entirely, first with a state-of-the-art research vessel and then with a beyond-state-of-the-art submarine, the Sea Rogue from which the game takes it name. These vessels make it practical to travel much farther — all the way to Britain, Europe, Africa, and into the Mediterranean, another veritable watery junkyard. And the Sea Rogue allows you to reach deep-water wrecks like the Titanic.

As I said, there’s a lot going on here. You have a crew to manage, who have CRPG-style statistics that improve with experience, assuming you invest in shore-based training every time they level up. Your relationships with different countries are affected by how much respect — or lack thereof — you show to their ships’ wreck sites; aggravate them too much and they’ll send their navies after you. You can hire research assistants, take on salvage contracts, even detect undersea mineral deposits and earn a finder’s fee.

Meanwhile up to five computer-managed competitors are doing the same things you are. One of them, the fellow named Evil Eddie, is particularly nasty, and will sometimes attack your vessel at sea or ambush your divers underwater. This means you need to make provisions for defending yourself, need to have some guns of your own available.

I absolutely love the premise, love the way it blends the unabashedly fantastic with the real-world subculture of wreck hunting. Half of the thick manual is given over to a list of every single one of those 150 ships that are waiting to be found, each and every one of them a real, documented wreck, ranging from Viking longboats to modern Soviet submarines. In order to earn full value for any treasures you recover, you have to ferret out the name of any ship you find from clues at the site, cross-referenced with the descriptions in the manual. The Titanic and Bismarck aren’t the only ships in this game that you’ve heard of before: there are also vessels like the Hunley, the Andrea Doria, the Lusitania, and much of the Spanish Armada to be found. If you approach your endeavors in the right imaginative spirit, you’ll feel a genuine shiver go up your spine when you discover one of these storied ships, and may just go scurrying off to Wikipedia to learn more about it.

Still, it’s possible that my love for the premise makes me more kindly disposed toward the game than it deserves. For it lacks the compulsive playability of Pirates!. The interface is clunky, and, while the big manual does a reasonably good job of telling which keys to press and where to click the mouse, it often fails to explain why you’re doing so; I must confess that I still don’t completely understand the sonar-scanning screen even after playing the game for a considerable number of hours. And then, for all that the developers strained mightily to give you lots of different things to do, from decoding radio messages to chasing down Pirates!-style treasure maps, it never quite gels into a cohesive whole. The competition aspect of the affair never feels all that urgent even when Evil Eddie starts shooting at you. It all becomes a bit samey sooner than it ought to, sorely lacking Pirates!‘s addictive kinetic quality; in the older game, you actually sail your ship from place to place with the joystick, where here you just plot a course on a map, hit a key, and jump instantly to your destination. Perhaps the game’s biggest weakness is the wreck-diving mini-game, which consumes far more time than anything else you do but plays like a not especially exciting board game, complete with an ocean floor made up of discrete squares. Again, the developers plainly tried to spice it up, by introducing roaming sharks that occasionally attack your divers. But there’s no variety from wreck to wreck to keep your interest up; you’ll quickly develop a rote approach to the task that works every time, one that is about as exciting as cutting your lawn (a task with which it has much in common).

In the end, then, Sea Rogue is more of a game that I want to love — that I sometimes manage to convince myself that I at least like — than one I really can enjoy over the longer haul. Call it a brilliant concept, imperfectly realized. In all the years since its release, there’s been nothing else quite like it. I remain convinced that there’s a great game in there somewhere, and I’d be thrilled to see the idea revived with richer and more varied content, ideally spanning all of the world’s oceans, with the sense of atmosphere that Sea Rogue‘s workmanlike graphics and sound struggle to inculcate. We have hugely successful games today in which you do nothing but drive a truck around a continent’s highways and byways. Why not one where you travel its seaways in search of treasures from the past?

(I’ve prepared a Sea Rogue download for you which should be fairly simple to get running under your platform’s version of DOSBox.)

Whatever else one can say about Capstone, someone there clearly had a real interest in marine archaeology. For in 1993, four years after Search for the Titanic, they returned to the scene of that crime with Discoveries of the Deep for MS-DOS. It’s a vastly better effort. Then again, how could it not be?

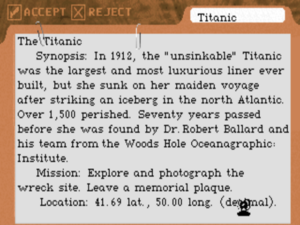

Discoveries of the Deep is an edutational product aimed at youngsters, and sports the sense of whimsy that Search for the Titanic so sorely lacked, including a credible darts game and a shoot-em-up arcade game in your boat’s galley, ready to play when all of this oceanography business starts to become too much. The main game is structured around seven missions which you may undertake in any order. Only one of them involves the Titanic; the others range from investigating airplane crashes in the Bermuda Triangle to disposing of underwater toxic waste. It plays as a simplified version of the premise we’ve been seeing over and over: sail out to the general vicinity of your goal, search from the surface until you pinpoint it precisely, then get into your submersible to complete your mission. Only the economic element is lacking, replaced with a refreshing focus on environmental science; you definitely won’t be looting the Titanic this time out. Although there’s not overmuch to the experience in the final analysis, what there is is colorful and good-hearted. One can easily imagine this game going down a treat in a classroom back in the day, and it still wouldn’t be a bad choice for a kid of the right age — about ten years old is probably the sweet spot — with an interest in the ocean and the things that lie beneath it. Chalk it up as a partial atonement for Search for the Titanic.

(Like Search for the Titanic, Discoveries of the Deep is available on GOG.com as a digital purchase.)

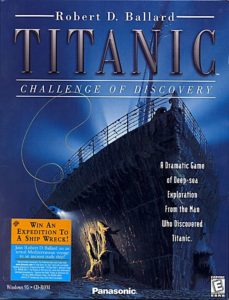

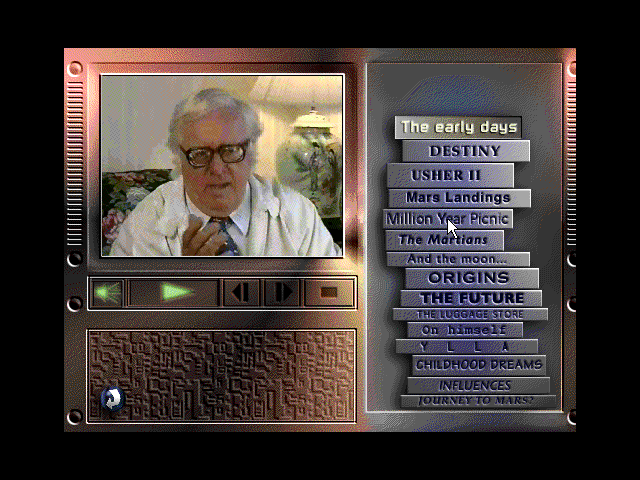

The last wreck-hunting game of this lineage to date appeared in 1998, the year after James Cameron’s film about the disaster rejiggered all of the pop culture surrounding the Titanic in a way which we’ll examine in my next two articles. Titanic: Challenge of Discovery is simultaneously one of a number of cash-in products made in response to the film’s enormous success and a throwback to an earlier era, when the ship existed in the public’s imagination primarily as a wreck. The game’s box copy would have one believe that Robert Ballard himself made it, declaring it “a dramatic game of deep-sea exploration from the man who discovered the Titanic.” This only serves as grist for the mill of Ballard’s critics, who have been muttering behind the scenes for decades now that he is a bit too eager for the limelight and the money that comes with it, having by now lent his name to a jumble of slapdash products like this one that’s about as large as the sunken Titanic‘s debris field.

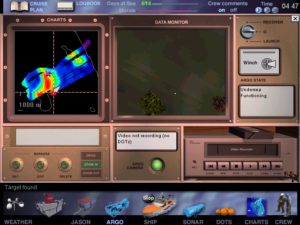

Challenge of Discovery was created by a “multimedia” studio rather than a games studio, an outfit called Maris Multimedia to be exact, and was published by Panasonic Interactive for Windows. It came rather late in the day of the multimedia boom, but otherwise bears all the hallmarks of its checkered lineage: a surfeit of video clips, including some featuring Ballard himself, and a paucity of worthwhile gameplay. I’ve written about the problems which plagued creations of this sort at some length elsewhere, so I won’t belabor those points here.

In this game, you’re expected to explore three shipwrecks: a man-of-war from the Spanish Armada, the Bismarck (whose wreck was discovered by Ballard in 1989), and finally the Titanic. But it’s painfully clear that far more attention was lavished on the video clips than the gameplay, which is slow, dull, and buggy, to the point that parts of the game are outright broken. Neither the traditional hardcore gamer demographic nor the different, more casual audience whom Panasonic was presumably trying to attract had anywhere near enough patience for this exercise in tedium. All told, it makes for a dispiriting capstone to a strand of games that had a lot of potential in their individual ingredients, but that no one ever quite managed to bake into a comprehensively delicious cake.

(You can find CD images for Challenge of Discovery by searching on archive.org. But, like a lot of shoddily programmed early Windows software, this game is a nightmare to get running on modern systems. I was finally able to succeed by using a Windows 95 — not Windows 98, mind you — installation running through Oracle VirtualBox. If you’re determined to try out this terrible game for yourself, this YouTube video will show you how to get your Windows 95 virtual machine going.)

Next time, then, we’ll turn to a very different way of approaching the Titanic as a gaming subject, and find out whether anyone had more luck there…

(Sources: the books Sinkable: Obsession, the Deep Sea, and the Shipwreck of the Titanic by Daniel Stone, Into the Deep by Robert Ballard and Christopher Drew, The Discovery of the Titanic by Robert Ballard and Ken Marschall, Raise the Titanic! by Clive Cussler, Beyond Reach: The Search for the Titanic by William Hoffman and Jack Grimm, and Titanic and the Making of James Cameron by Paula Parisi; Crash! of June 1984 and October 1984; Your Computer of July 1984; Zzap! of June 1986; Ahoy! of April 1987; Games Machine of April 1990; Computer Gaming World of July 1992 and December 1993; National Geographic of December 1986.)